Abstract

Breast surgery was one of the most dynamic fields of medicine which benefited from significant progress during the last decades. The transition from aggressive and mutilating amputations to conservative, oncoplastic and reconstructive techniques has been constant, offering improved and rewarding results, viewed from both, oncological and aesthetical perspectives. Conservative techniques, especially those which preserve the nipple areola complex, are followed by improved patient’s perception of their body image, confidence and sexuality, with the only drawback of increased anxiety linked to recurrence risk.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading cause of death due to cancer in women all over the world, accounting for 16% of cancer deaths in adult women [1]. Individual country- and cancer site- specific studies suggest that the age-adjusted incidence of breast neoplasia has increased in European populations over the past two decades [1,2]. Data on incidence for breast cancers in eastern and central European countries started to approach levels in northern and western Europe, where rates were already high [2,3].

Important advances in early detection, diagnostic methods, surgical and medical treatments have improved the prognosis of the disease, and the new forms of treatment have decreased adverse side effects that formerly plagued many patients. Approximately 50% of women with breast cancer can now expect to survive at least 15 years, and over 95% of women with localized disease will survive 5 years or more, according to American Cancer Society [4].

Despite these advances, however, the diagnosis of, treatment of, and recovery from breast cancer may provoke severe physical and psychological complaints.

Discussion

Psychological impact of breast cancer

Breast cancer survivors most frequently report experiencing emotional distress (depression and anxiety symptoms), intrusion and avoidance; numbing of responsiveness and avoidance of feelings, in relation to cancer and its treatment. Breast cancer seems to be stressful because this disease and its medical treatment can afflict the sense of femininity, perceived sexuality, and fertility.

There is considerable evidence that breast cancer and its treatment are associated with problems with body image, sexuality, and sexual functioning. Findings indicate that the diagnosis of breast cancer is associated with heightened levels of negative emotions and psychological distress, especially symptoms of anxiety and depression. Elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression near the time of diagnosis are typically reported in 30% to 40% of patients [4].

Many of the studies show a significant relationship between psychosocial factors and survival, but this link may be bidirectional. On one hand severe prognosis factors (stage, tumor biological characteristics), which highly influence mortality rates, may also cause depression for patients who understand very well their statistical significance. On the other hand, a good physiological status may influence the patient’s adherence to treatment, which results in better survival rate.

The extraordinarily stressful aspects of the disease and its treatments cause psychiatric disorders to occur more frequently, especially in patients with advanced breast cancer and/or young age. It is estimated that 20-30 % of patients will have a formal psychiatric diagnosis, the most common being depression [5].

Young women have lower incidence rates of breast cancer compared to older women, but the incidence increases at a faster rate. Their cancers tend to have a higher grade with poorer prognostic characteristics, resulting in a higher risk of recurrence and thus, the need for more aggressive treatment regimens and less conservative surgery. But these young/ sexually active patients demand and cannot cope with poor cosmetic results, as research shows that younger women with breast cancer experience a lower quality of life after cancer compared to older women. In part, this lower quality of life results from the effects of medical treatment and surgery, as removal of the breast tissue results in more negative feelings regarding body image, particularly for young women [6,7].

With hormonal treatment, many younger women experience the sudden onset of menopause, with the attendant symptoms of hot flashes, decreased sexual desire, and vaginal dryness. These physical effects contribute to a high level of sexual concerns and distress for young women [5,8].

Psychological benefits of conservative surgery for breast cancer.

Breast surgery was one of the most dynamic fields of medicine which benefited from significant progress during the last decades. The transition from aggressive and mutilating amputations to conservative, oncoplastic and reconstructive techniques has been constant, offering improved and rewarding results, viewed from both, oncological and aesthetical perspectives.

The better the disease is understood and the more efficient the treatment becomes and the lower the mortality rates will be. In this context appropriate consideration of quality of life factors is of increased importance and health professional scaring for women diagnosed with breast cancer should consider these issues throughout the woman’s treatment and into survivorship.

Tissue-sparing approaches to primary treatment and reconstructive options provide improved cosmetic outcomes for women with breast cancer. Research has suggested that conservation or restitution of the breast should ease the negative effects of breast cancer on women’s sexual well-being [5,6]. The benefit of the type of primary surgery for breast cancer occurs largely in areas of body image and feelings of attractiveness, with women receiving lumpectomy experiencing the most positive outcome [6,8,9].

A study by Yureket concluded that women who received modified radical mastectomies with reconstructive surgery had greater disruptions in sexual functioning than women who received modified radical mastectomies without reconstruction and women who received lumpectomy surgery [10].

But the association between disease characteristics and psychological distress is far from simple, as it includes many variables (disease stage and prognosis, diagnostic procedures and treatment options) that superpose on patient’s characteristics and predictors of distress.

Evidences that breast conservation or reconstruction offers more psychological protection for younger women suggest that sexuality seems to play an important role in the behavioral dynamic [8,9,11].

Women with breast conservation do rate their body image more highly and are more comfortable with nudity and breast caressing. Differences in overall psychosexual outcomes between mastectomy and breast conserving surgery include that women with breast conserving surgery have better preserved body image, earlier resumption of sexual activity and maintained breast caressing during sexual activity [11,12,13].

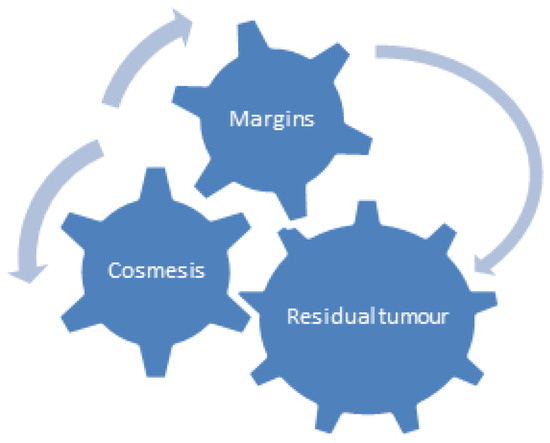

Conservative mastectomy should balance the oncological safety of the total glandular excision (offered by the traditional total mastectomy) with the satisfactory aesthetic result (offered by the conservation of the skin envelope and the nipple areola complex) (Figure 1).The use of expanders or fixed volume implants ensures a high quality reconstruction that leaves the patient with a new normal looking breast [14,15].

Figure 1.

Conflict of interests.

Conclusions

Although limited research exists about body image and sexuality and appropriate interventions, a number of conclusions can be drawn. Traditionally, the management of breast cancer has focused on mortality and morbidity. The management of breast cancer significantly influences both body image and sexuality, and only recently these physiological problems received their recognition. With better treatment options, more long term, disease free survivors will need their quality of life issues addressed.

Conservative techniques, especially those which preserve the nipple areola complex, are followed by improved patient’s perception of their body image, confidence and sexuality, with the only drawback of increased anxiety linked to recurrence risk.

Nowadays, personalized treatment management plans, that include aesthetic satisfaction of breast cancer patients coupled with oncological safety, should be the objective of modern breast surgery.

References

- Donepudi, M.S.; Kondapalli, K.; Amos, S.J.; Venkanteshan, P. Breast cancer statistics and markers. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2014, 10, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cancer Facts and Figures. Available online: http://www. cancer.org.

- Arnold, M.; Karim-Kos, H.E.; Coebergh, J.W.; Byrnes, G.; Antilla, A.; Ferlay, J.; Renehan, A.G.; Forman, D.; Soerjomataram, I. Recent trends in incidence of five common cancers in 26 European countries since 1988: Analysis of the European Cancer Observatory. Eur J Cancer 2015, 51, 1164–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Compas, B.E.; Luecken, L. Psychological Adjustment to Breast Cancer, Current. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 11, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hoptopf, M.; Chidgey, J.; Addington-Hall, J.; Lan, L. Depression in advanced disease: A systematic review Part 1: Prevalance and case finding. Palliat. Med. 2002, 16, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, J.H.; Desmond, K.A.; Meyerowitz, B.E.; Belin, T.R.; Wyatt, G.E.; Ganz, P.A. Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Schover, L.R. Sexuality and body image in younger women with breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 1994, 16, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom, D.H.; Porter, L.S.; Kirby, J.S.; Gremore, T.M.; Keefe, F.J. Psychosocial issues confronting young women with breast cancer. Breast Dis. 2005–2006, 23, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenqvist, S.; Sandelin, K.; Wickman, M. Patients' psychological and cosmetic experience after immediate breast reconstruction. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 1996, 22, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yurek, D.; Farrar, W.; Andersen, B.L. Breast cancer surgery: Comparing surgical groups and determining individual differences in postoperative sexuality and body change stress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilmoth, M.C. The aftermath of breast cancer: An altered sexual self. Cancer Nurs. 2001, 24, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurek, D.; Farrar, W.; Andersen, B.L. Breast cancer surgery: Comparing surgical groups and determining individual differences in postoperative sexuality and body change stress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rowland, J.H.; Desmond, K.A.; Meyerowitz, B.E.; Belin, T.R.; Wyatt, G.E.; Ganz, P.A. Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bălălău, C.; Voiculescu, S.; Motofei, I.; Scăunasu, R.V.; Negrei, C. Low dose Tamoxifen as treatment of benign breast proliferative lesions. Farmacia 2015, 63, 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Jecan, C.R.; Hernic, A.D.; Filip, I.C.; Răducu, L. Clinical data related to breast reconstruction; looking back on the 21th century and forward to the next steps. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2015, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors. 2016 Răzvan V. Scăunașu, Traean Burcoș, Ștefan Voiculescu, Bogdan Popescu, Șerban V. Berteșteanu, Oana-Denisa Bălălău, Nicolae Bacalbașa, Cristian Bălălău