History

Even though body piercing has only become more popular in the recent years, usually as a fashion or identity statement, the discovery of piercings, carvings and sculptures in ancient burials of the Inka, Moche, Aztecs and Mayans stand as proof that the practice has been around for thousands of years and probably represented rites of passage, assigning the bearer to specific social or age groups [

3,

4]. Earlobe piercings are also mentioned in King James Version of the Bible, written in 1611, in the Genesis Chapter [

4].

Genital piercings also have a significant historical background. The Kama Sutra, the ancient text on the art of love, probably written by the Sanskrit scholar Vatsyayana between the first and the sixth century AD, presumably has the oldest known reference to penis piercing. According to this writing, genital piercings were a mean of increasing sexual pleasure [

1,

4,

5].

The piercing of the glans penis with a bone derives from early tribes in Borneo - the Dayaks- and was probably a rite of passage from adolescence to manhood [

4,

5,

6].

However, enhancing sexual pleasure and rites were not the only reasons for the practice of piercing. In contrary, infibulation, the process of piercing the lips of the foreskin with a clasp or a ring, was performed to insure chastity. Infibulation is mentioned in the writings of Celsus, the Greek philosopher, but he offers little information on the reasons for performing this procedure, one of them being preserving the voice. Later on, in the 18th century, the German surgeon Carl Augustus Weinhol pleaded for mandatory infibulation for criminals, beggars, chronically ill, servants and lower ranked soldiers, who were all considered unfit to procreate. His ideas were dismissed. However, between the late 18th and 20th century, during the medical panic over masturbation, circumcision and infibulation were performed to cure this "disease, which was "scientifically proven" to be dangerous, debilitating and deadly [

7].

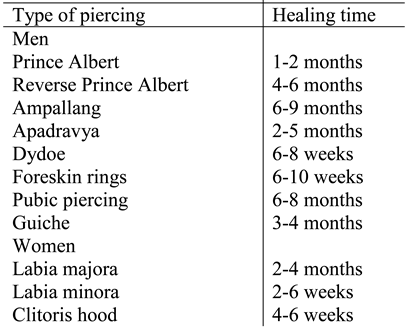

Male piercings

Prince Albert or "dressing ring" is one of the most renowned and most common male genital piercings. It is named after the husband of Queen Victoria of England. He allegedly had a piercing to secure his penis in the tight trousers which were very fashionable in the Victorian times. Since there is no evidence to support this story, it is probably just a modern myth designed to romanticize this piercing. It perforates the urethral meatus and the corona, on the ventral side of the penis. It causes intense urethral stimulation during intercourse. However it frequently affects urinary flow and aim and men wearing this piercing sometimes need to sit during urination [

2,

6,

8].

Reverse Prince Albert is similar but the piercing perforates the urethral meatus and the dorsum of the penis and it heals more slowly [

4,

5]. Ampallang is a not so common piercing deriving from the Dayaks in Borneo. It is a transverse piercing and the barbell is placed through the glans of the penis, either through or above the urethra. The procedure is quite difficult and the risk of bleeding is high. Therefore, it is mandatory that an experienced piercer performs this procedure. They do not increase sexual pleasure in penetrative sex [

4,

5,

8].

Apadravya is also a piercing which had been used from ancient times and was described in the Kama Sutra. It is similar to the ampallung but the barbell is placed vertically through the penis glans and traverses the urethra. It is also uncommon. Since it passes through the urethra the sterile urine promotes healing [

4,

5,

8]. The Dydoe penetrates the coronal ridge. It is done in circumcised men and it is assumed to have Jewish origin. It is supposed to replace the sensitivity decreased by the removal of the foreskin in circumcision. Dydoe bearers can opt for one or multiple such piercings [

4,

5,

8].

Foreskin piercings are only possible in uncircumcised men or in men with foreskin restoration. When both sides of the foreskin are closed with rings it acts as a chastity belt, thus making intercourse difficult [

4,

5,

7,

8]. The frenum is a piercing of the frenulum. It surrounds the glans and should only be done in uncircumcised men because in circumcised men the frenulum has poorer vascularization and the healing process takes longer [

4,

8].

The pubic piercing, also called "The Rhinoceros horn" is situated at the base of the penis and it said to increase woman's clitoral sensations during intercourse [

4]. Hafada piercing is located on the scrotum, usually on the lateral side. It originated as an Arabian rite of passage [

4,

8,

10]. The Guiche originates in the islands of the South Pacific. It is a pierce located on the perineum, on the midline or lateral to the midline. When it is placed through the anus it is called an Anal Ring [

4,

8,

10].

Female piercings

Piercings are also more and more frequent in women, even though when it comes to them there are some legal issues to be considered, as this procedure has been categorized by the World Health Organization as female genital mutilation (FGM). FMG includes ritual and non-medical operations involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia and amputations or incisions in the interior of the vagina. Genital piercings and labioplasties both fulfill the criteria for type IV FMG- "other injury to female genitalia", and, in countries such as UK, any person performing female genital piercing could be guilty of criminal offence. This, however, doesn't seem to stop women from wanting piercings and piercers from performing the procedure [

4,

11,

12].

In women, the clitoral hood and both labia minora and labia majora are common sites of piercing. Chastity rings in females can be done by perforating both labia majora or both labia minora and bridging the gap [

4]. The clitoris hood piercing is the most common female genital piercing. The ring can perforate the clitoris either vertically or horizontally. They are said to be very pleasurable for women wearing them during sexual intercourse. Triangle piercing is a type of deep piercing of the clitoral hood, located at the ventral part of labia minora, between the labia and the clitoral hood [

4,

8].

Christina piercing is a vertical piercing which perforates the body of the clitoris and exits on the lower part of mons pubis. It is not very common because the healing time is long [

4]. Princess Albertina is the female version of the Prince Albert piercing in which the ring enters through the urethra and exits between the urethral and vaginal openings, thus perforating the dorsal wall of the urethra [

4].

Reasons for getting piercings

Over the years a lot of negative stereotypes were attributed to the bearers of piercings. They were considered criminals, with poor performance in school, homosexual or sadomasochists, among others. Piercing became more popular in the 1980' when the punk and the gay cultures took over this habit as a protest against the conservative norms of society. The popularity of both piercings increased in the later years and, as they became fashionable accessories, people of all social classes, adults and teenagers picked up this practice [

3,

13].

Studies show that the main reasons for getting genital piercing are sexual enhancement, proclaiming ownership of the body, ritual, adventure, feeling unique and beautification [

13].

A study performed by Caliendo et al in 2004 on 146 pierced persons, 63 of which were women and 83 men, showed that the main reasons for getting a genital piercing in both men and women was to help them express themselves sexually and because it improved their personal pleasure with sex [

13].

Ferguson showed in a study performed on 134 pierced persons that many women reported their first orgasm after getting a clitoris piercing [

6]. Reclaiming the body after traumatic events or sexual abuse has also been shown to be reasons for getting genital piercings in some studies. The piercing help these women heal psychologically. Infibulations can be performed to help them defend against further intrusion [

3,

14]. A study performed by Young et al in 2009 on 240 women with genital piercings showed that 58% of them had experienced some sort of abuse (physical, emotional or sexual) and 35% experienced forced sexual activity [

14].

Complications

Studies show that the complication rate in genital piercings is between 10-15% [

14]. Generally adverse reactions are minor and include redness, swelling, minor bleedings or exudation [

2]. Bleeding usually occurs during the procedure and immediately after. Sometimes blood loss can be important [

1].

Patients are prone to getting bacterial, viral or fungal infections. Sometimes those are due to the use of nonsterile instruments but usually they are determined by the person's own periuretharal flora or from feces contamination, as a result of poor hygiene during the healing process [

1,

14]. Serious bacterial infections have been described such as Fournier Gangrene determined by

Group A Streptococcus, mixed Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobic organisms and tetanus [

1,

2,

15,

16].

Viral infections, especially hepatitis C, but also hepatitis B and D and HIV can be transmitted, especially if the equipment has not been sterilized. Intraurethral condyloma acuminata has also been reported in men with genital piercing and the author suggests that the piercing favored the infection [

1,

9,

17].

As regard to sexually transmitted diseases, the results of the studies are contradictory. Therefore, while some suggest that genital piercings increase the risk of acquiring sexually transmission, other studies have failed to demonstrate a connection. However, since genital piercings worn by one or both partners could break the condom or diaphragm during intercourse, using two condoms or looser fitting condoms is recommended to avoid sexually transmitted infections [

9,

18].

Bacterial infections are treated with topical or systemic antibiotics. The piercing may be kept in place to promote drainage and avoid abscess formation [

1,

4]. Allergic reactions to the metals, especially if the piercing is made of an alloy containing nickel, can occur in men and women who are allergic to nickel [

1,

4,

13]. In females, other adverse reactions include scarring and keloids [

1,

4,

13].

In males there have been documented cases of urethral rupture and splitting of the urinary stream, priapism, paraphimosis, hypospadias, fistulas and urethral strictures. Two cases of squamous cell carcinomas at the site of Prince Albert piercings have also been reported in two men who had hepatitis C infection and were HIV positive [

1,

4,

8,

9,

19,

20].