Abstract

Sigmoid diverticulitis is a common disease characterized by a well-standardized diagnostic approach and treatment. Colorectal cancer is the third most common malignancy worldwide, irrespective of gender. In 2020, CRC global-related mortality rate was estimated at 935,173 cases, with an incidence of 9.3% in men and 9.5% in women. The diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is always made by performing a contrast-enhanced-computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen. Current diagnosis guidelines do not recommend the use of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for further and more precise assessment of a suspected sigmoid diverticulitis diagnosed by CT. Early lower-gastrointestinal (lower-GI) endoscopy is rarely conducted; thus, the diagnosis delay could have a negative impact over the oncological outcome of the disease. Few and scarce data can be found related to this issue, with only a recent Swedish study paying attention towards early identification of neoplastic disease residing on a background of sigmoid diverticulitis, facilitated by MRI. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the feasibility of systematically performing an abdominal MRI included in the primary assessment of acute diverticulitis already diagnosed by CT, in order to argument in favor of an early lower-GI endoscopy where a positive MRI for neoplasia is found.

Introduction

Early diagnosis of a malignant pathology is a key element, that can facilitate early treatment with impact on the overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) interval of the cancer involved [1]. This is especially true for digestive malignancies, where symptoms are scarcely present and are unspecific and insensitive.

Sigmoid diverticulitis is a common disease in Western society, characterized by a standardized diagnostic and treatment approach. In the general population, diverticulosis is present in a percentage ranging between 33 and 66%, according to descriptive global population studies. Out of these patients, between 10 and 25% will develop an acute diverticulitis episode [2].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States. In 2023, approximately 153,020 individuals will be diagnosed with CRC and 52,550 will die from the disease, including 19,550 cases and 3750 deaths in individuals younger than 50 years. The decline in CRC incidence slowed from 3–4% annually during the 2000s to 1% annually during 2011–2019, driven partly by an increase in individuals younger than 55 years of 1–2% annually since the mid-1990s. According to recent data provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the number of CRC cases should increase in the next decade [3]. To this date, the incidence of sigmoid colon cancers that present with an inflammatory onset is not reported in literature.

When looking at the management of sigmoid diverticulitis, emergent surgical intervention is an increasingly less used approach. A delayed intervention following an acute episode is also a conduct that now seems to be less often used, in contrast to such an attitude that was wide-spread and considered to be the standard of care in the past [4,5].

Although the last decade was characterized by remarkable progress in medical imagery, the steps undertaken for an early diagnosis of an acute sigmoid diverticulitis always and solely rely on performing a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen in the emergency setting. The initial treatment of choice, even in the presence of a small perforation associated with the formation of an abscess (that can respond favorably to conservative therapy), most often, is not surgical. At an interval of a few weeks after the acute episode, a lower-gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy (colonoscopy) is strongly recommended. In France, the ideal interval recommended at which, a post-sigmoid diverticulitis prophylactic sigmoidectomy should be performed, is of two months [6]. The French High Authority for Health (HAS) does not recommend the use of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) investigation for the evaluation of sigmoid diverticulitis, previously diagnosed by CT. Current international studies, somewhat focus in addressing this issue.

Early lower-GI endoscopy is rarely performed in the acute setting, bearing in mind the fact that such a gesture is too risky, and can be followed by major complications requiring surgical treatment in emergency, such as a serious perforation associated with septic shock. In the current daily practice, where any medical invasive act can be subjected to a specialized assessment from a legal point of view, an early unnecessary colonoscopy, which can expose the patient to a major risk, can be legally sanctioned. Colic perforation occurring during a colonoscopy performed in the absence of any risk factors, was recognized at a time, as a non-faulty medical act, an investigation-associated medical accident. In France, The Court of Cassation has recently changed this point of view, stating that a perforation in this context should be interpreted as an iatrogenic gesture from the part of the operator [7]. It is therefore understandable that many gastroenterologists prefer to wait until the inflammatory process fades, prior to an invasive procedure.

However, in cases where the initial pathology should in fact not be a simple inflammation but a cancer mimicking inflammatory diverticulitis, CT might not help to properly guide practitioners towards the correct diagnosis and management. Regarding this matter, The Coloproctology Society of Great Britain and Ireland, reported in 2011, that a stenotic inflammatory lesion of the sigmoid colon cannot be differentiated from a neoplastic origin, using CT as a single imaging tool [8].

Lower-GI endoscopy is the only test that can corroborate or refute the initial malignancy suspicion. In this direction, the delay of the diagnosis has an impact over the therapeutic result. On the other hand, there are reports of situations where CT leans towards an inflammatory neoplasia, which in fact, at pathology analysis proves to be a common inflammation of the sigmoid colon.

The latest recommendations intended for gastro-enterologists, regarding the optimal approach for the treatment of CRC, do not take into account the particular case of an inflammatory tumor presenting in the emergent setting with the characteristics of a sigmoid diverticulitis. MRI is particularly cited for the assessment of distant liver metastases and for the local staging of rectal cancer [9]. No recommendation is made in relation to the very special case of an inflammatory tumor.

Already in 2004, Snyder et al. began to wonder about the opportunity of using MRI for the evaluation of patients with sigmoid diverticulitis. He recognized that MRI provides multiple advantages in the diagnosis of inflammatory pathology. Despite this, the major disadvantages reported for daily practice, by this study were cost-related, time of wide-scale implementation, failure to be able to use this technique in claustrophobic patients and carriers of metallic implants [10].

Although the study launched the idea that future studies should be conducted to better compare CECT and MRI in this context, the subsequent attention for this topic is particularly scarce. In addition, the problem of differentiating a sigmoid inflammatory malignant tumor had not been taken into account. In a study from 2012, Lee et al. have questioned about how to distinguish a sigmoid cancer from post-radic sigmoiditis, an entity often overlooked, encountered at patients treated for cervical cancer with brachytherapy, a procedure that may affect the rectum [11].

It was not until a recent Swedish publication, when the authors focused upon the issue of identifying neoplastic disease on a background of diverticulitis, while assessing the impact of MRI [12]. The authors acknowledged that sigmoid colon cancer can mimic the signs and symptoms typical of a purely inflammatory diverticulitis. The purpose of their study was to compare CECT and MRI, while balancing their specificity and sensitivity in order to find the best tool in the differential diagnosis process. The Swedish study showed that the sensitivity of CECT to diagnose neoplastic sigmoid pathology was 66.7%.

Specificity for diagnosing diverticulitis was, however, 93.3%. On MRI, particularly T2-weighed sequences, sensitivity was 100% for colon cancer and the specificity was 100% for diverticular diverticulitis. This paper, by Öistämö et al. cites that of Buckley et al. in order to discuss these results. Indeed, MRI is more efficient than CECT, because it offers better resolution in terms of contrast, which allows an accurate assessment of the thickness of an inflamed bowel wall and the description of typical features of cancer, such as the focal thickening with sudden transition between regions of normal colon and regions of thickened colon with pathological traits [12,13]. To this date, to our knowledge, there are few studies performed to assess the impact of MRI for early diagnosis of colon cancer in an acute diverticulitis context.

Thus, the purpose of this prospective study is to evaluate the systematic use of an abdominal MRI in the assessment of acute diverticulitis already diagnosed by CT, in order to push for an early lower-GI endoscopy, in MRI suspicious lesions for neoplasia. If such a conduct should be proven advantageous to apply, it would help in not losing valuable weeks in the treatment of inflammatory neoplastic lesions of the sigmoid colon.

Materials and Methods

A total of 30 patients presented to the Clinical Hospital “Avram Iancu” of Oradea were selected for enrollment in the study, during the period of 01.01.2021-31.12.2021. The study was carried out by obtaining the consent of the patients and respecting the ethical conditions of the hospital.

Inclusion criteria:

- Patients with the clinical and imaging scenario (CECT) characteristic for a diverticular pathology (regardless of the Hinchey stage of the CT diagnosis)

- Patients conservatively or surgically treated for complicated diverticular pathology

- Patients who were subsequently followed via imaging studies and endoscopy for initial acute diverticular pathology

- Patients who signed the informed consent for the study, according to the Informed Consent Form of the Department of Surgery

Exclusion criteria:

- Patients which due to subjective reasons refused to be subjected to a combined abdominal-pelvic MRI examination

- Patients who were discharged on request after receiving conservative treatment

- Patients who were NOT subsequently followed via imaging studies and endoscopy for initial acute diverticular pathology

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 24 patients were enrolled included in the study. The table below (Table 1) outlines some elements accounted for the patients who were enrolled in the study while listing the order in which they were recruited.

Table 1.

Patients enrolled in the study

All patients were initially admitted with spontaneous pain in the left iliac fossa, with or without fever. Each patient had laboratory biochemical tests suggesting an inflammatory syndrome. Clinical examination was characterized by pain on deep palpation in the left iliac fossa, with or without abdominal rebound tenderness or defense.

An abdominopelvic CECT was performed to certify the diagnosis where the clinical suspicion was that of acute diverticulitis of diverticular origin.

CT images with and without intravenous iodinated contrast injection were obtained. Images with injection were acquired only in portal phase with cross-sections of 5 mm. Once the initial suspected diagnostic was confirmed, patients were treated with hospitalization and intravenous followed by oral antibiotic therapy with third generation Cephalosporins and Metronidazole.

During the hospitalization period, each patient was subjected to an abdominal MRI in order to identify and select those patients who could possibly present elements that suggest an underlying neoplasia of the colon which presented as an inflammatory disease (sigmoiditis).

The acquisition of the MRI images was obtained using a 1.5 T system (Advanto Q, Siemens) with a type body phase array coil antenna. The examination was mainly based on diffusion and fast spin echo T2-axial developed sequences. If deemed necessary by the radiologist, some sequences have also included section-plans in coronal or sagittal view. At the beginning of this study, even T1-weighted sequences with and without Gadolinium injection (Gadovist 1 mmol / mL, injection of 8 to 15 mL depending on the patient) were acquired, after several investigations, T2-sequences were preferentially obtained for the later cases. The used voxel size for the images was of 3.5 x 3.5 x 9 mm. The images were acquired only by the MRI apparatus of our facility and they were interpreted only by the local team of Radiology at SCM CJ. In order to standardize the image acquisition method and terms of interpretation of the iconographic elements, patients who undertook the examination in another institution (due to logistical reasons and waiting times) were not included in the study.

The acquired MRI images researched features were mainly morphological, although the signal strength was also considered. In regard to the morphological findings, aspects such as the length of a possible stenosis, the degree of infiltration of peri-colic fatty tissue, the contact angle between the “healthy” zone and the “sick” one, were taken into consideration as suspicious. One other important factor that was especially taken into account was the change in the ADC (apparent diffusion coefficient), especially in the presence of peri-colic abscess. Indeed, diffusion images appear with a similar contrast to T2-weighed acquisitions, because they were acquired using a repetition time (RT) that can be rather long in concordance to an echo-time (ET) of approximately 74-100 milliseconds. Involuntary patient movements during the examination and tissue vibration caused by the systolic contraction of the heart until capillary perfusion is reached, can provide very similar effects to images acquired in pure diffusion. In order to limit the extent of such technical problems, although the method is not absolute, quantitative description of the results was obtained by weighing the ADC. The signal intensity in suspicious areas was also closely observed as for the hyper-signal in T2-weighed sequences. Image acquisition using this approach increases the global execution time of the MRI.

For all of the patients where a malignant pathology was suspected at imaging tests, a short colonoscopy (recto-sigmoidoscopy) with biopsy of the affected segment, was performed. These were the patients where MRI or abdominal CECT scans were in favor of a possible malignancy. The endoscopic examination was performed early, before the usual waiting weeks as in the situation of a “classic”/non-suspicious sigmoid diverticulitis. No biopsy was performed in the cases where endoscopic examination had proved negative, with the complete regression of the inflammatory phenomena.

- Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows and Microsoft Excel. The normality of the distribution of continuous numerical variables was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. The differences between the means of the continuous quantitative variables were evaluated using the Student test (t-test), respectively ANOVA (in the case of the presence of several categories). The analysis of the differences between the averages of continuous variables whose distribution does not respect the condition of normality was done with the help of the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively Kruskal Wallis, in the case of the presence of several categories. To analyze the differences between the qualitative variables, the Z test (Z-test) and the Chi square test (χ2) were used. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of the 24 patients admitted to the study, with confirmation of abdominal-pelvic CT with acute diverticular pathology, there were 6 women and 18 men. The mean age of the patients was 55 ± 16 years (95% CI: 29-80 years) with the youngest patient at 24 years and the oldest at 86 years.

Following clinical examination, all patients experienced deep pain in the left iliac fossa, with or without abdominal defenses or tenderness.

The clinical suspicion was that of acute diverticulitis. For the definite diagnosis, an abdominal-pelvic CECT examination was performed with intravenous iodinated contrast agent (Iomer) administration. All CT slices were of 3 mm. One third of patients (36%) had a Hinchey Ia stage, followed by Hinchey III (20%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hinchey classification of patients in our study.

The abdominal-pelvic CECT raised the suspicion of malignancy only in two cases. Four of the patients had a perforation with minimum amount of pericolic pneumoperitoneum, patients that were not subjected to upfront surgical management, but underwent conservative antibiotic therapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

MRI interpretation.

A peri-sigmoid abscess associated or not to the presence a pneumoperitoneum was diagnosed in three cases. Two of these patients were initially treated with antibiotic therapy, without the need for either percutaneous or surgical drainage. This approach was chosen because the identified collections’ diameter was less than 5 cm.

For the last patient identified with a peri-sigmoid abscess without a diffuse pneumoperitoneum noticed at CECT, the surgical team performed an emergent laparotomy in order to remove the diffuse purulent collections originating from the perforated sigmoid colon; the chosen elective emergent surgical approach was that of a peritoneal lavage and drainage. In the same situation, colonic resection was performed remotely, in a second stage, also facilitating for an MRI to be performed during the initial hospitalization.

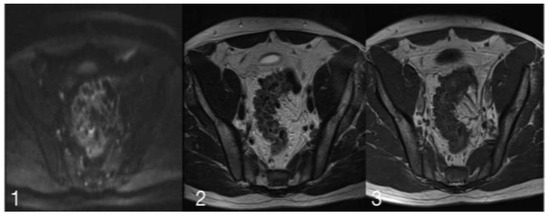

Among all patients included in the study, MRI detected suspicious images in three cases. In two patients, the MRI interpretation provided was inconsistent with the CECT images. In the first of these two cases, MRI formally excluded the existence of a neoplastic niche, even though CECT images were highly specific for such a scenario; in the other case, MRI highlighted an evocative aspect of an expansive process of the sigmoid, where the scanner did not find suspicious processes. The images below show the morphological and signal characteristics that allowed radiologists to hypothesize for malignancy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(1) is a diffusion image with a slice thickness of 6 mm, ET of 74.00 ms and RT of 1900.00 ms. (2) shows a-T2 weighed acquisition, with a slice thickness of 4 mm, ET of 125.00 ms, and RT of 4840.00 ms. (3) is a T1 Turbo Spin Echo image with a slice thickness of 4.5 mm, ET of 12.00 ms and RT of 452.00 ms.

The iconographic MRI evaluation permitted to lay emphasis on the morphological characteristics as well as on the signal. In the presented images, a lack of/low signal in T2 can be observed. The diagnosis of sigmoid diverticulitis may be regarded as one with high probability, but this lack of signal intensity is not found in such a distribution where high signal is present. For this, and for the aforementioned reasons, a high suspicion for a neoplastic lesion in an inflammatory context was stipulated.

Regarding the third patient, for whom MRI testing was positive for a probable neoplastic niche, CECT images were also highly suggestive the presence of a malignant pathology.

The patient, whose MRI images were not specific for the presence of an evident neoplastic lesion, undertook several colonoscopies that revealed a significant but surmountable sigmoid stenosis, probably of malignant origin. For the same patient CECT scans, performed twice, were also in favor of an invasive process developed in an inflammatory context. It is appropriate to note that the repeated-leveled biopsies performed during diagnostic procedures, have never found evidence of the existence of a neoplastic process. Despite of this, several gastroenterologists raised serious doubts on the reliability of the histological results. Indeed, they considered that, given the macroscopic extent and volume of the suspicious lesion and because of the inflammatory context, biopsies could have been made away from the malignant core, an exploratory statement always mentioned in the exam report. MRI was, in this specific case, the only test that went against the hypothesis of a malignant lesion. Sigmoidectomy was finally conducted in this patient. The examination of the surgical specimen allowed to definitively exclude the presence of a malignant pathology. Although statistically of any value, this situation might suggest that MRI is an examination with a good negative predictive value (NPP) in such a context. For the 24 patients in our study the medical team assessed the need of an endoscopy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Digestive endoscopy performed during hospitalization.

Recto-sigmoidoscopy was also early performed in a patient where both imaging tests were concordant for tumor involvement. Endoscopic examination led to formally eliminate the existence of a malignant neoplasia, while also excluding the need for surgical resection.

Of the total number of patients who underwent biopsy (endoscopic or surgical resection), two of the patients had inflammatory/abscessed sigmoid cancer; Hartmann resection was performed urgently for one of the patients with substantial pneumoperitoneum. The second patient with suspected malignancy was scheduled for sigmoid resection with a cancer within 4 weeks after the acute local inflammatory onset.

Discussions

The idea for this study was born out of a practical, almost-daily situation that surgeons and radiologists face. The physicians were put in a situation where a typical diverticulitis diagnosed and supported by best practice, proved to be an inflammatory malignant tumor of the sigmoid. While following the national and international guidelines, the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis is performed by an abdominopelvic CECT scan, usually undertaken in the emergency setting, followed by a portal time image acquisition. The proposed initial treatment is conservative, advocating for general i.v. antibiotics and analgesic therapy, usually in the hospital setting. Currently, in the presence of uncomplicated diverticulitis, some authors even consider a personalized-tailored approach at home, without therefore providing hospitalization [14].

It may be that, following the rules of good conduct and the supported recommendations of certified specialized societies, patients with sigmoid cancer are not diagnosed at time. The loss of a few weeks may prove decisive in the choice of treatment and chances of recovery. The recommendations for the scheduled delayed surgery for diverticulitis, where such approach is indicated, advocate that the colonic resection is performed at least two months after the most recent acute inflammatory episode has passed [15].

Stipulating a diagnosis of sigmoiditis of either undetermined or diverticular origin, while in the presence of colon cancer, can have a material impact on the management and outcome of the disease. Although recent studies found in the literature do not clearly and accurately estimate the colonic cancer growth rate and its’ evolutionary process from one stage to another, survival rates published by the American Cancer Society (ACS), indicates that ’between stage IIA and IIB stage there is a difference of 24% in terms of 5-year-survival rate, 87% for the former and 63% for the latter stage [16]. The difference between these two stages is represented by the presence or absence of a serosa breach. All of these considerations support the principle of seeking additional means to improve earlier diagnostic techniques. The presented approach in this study, therefore seems more than justified.

Data concerning the number of tumors in the sigmoid, having an initial presentation with characteristics similar to purely inflammatory lesions are absent from the literature. Only the study of Öistämö et al. [12] considers the use of MRI imaging tests to differentiate between cancer of the sigmoid and diverticulitis. In 2012, The Collegial Reunion of University Professors in Hepato-Gastroenterology of France, listed MRI as a non-mandatory nor recommended examination for cases of acute diverticulitis [15]. These contradictory conclusions presented by literature, in addition to the willingness to explore new diagnostic tracks that seem to have good prospects for development, led to evaluate MRI as an additional mean, other than the abdominopelvic CT, for the decision-making for sigmoid inflammation management [17].

Challenges include: contraindications MRI, limited availability to examination, set the CT approach as the gold standard for acute colonic diverticulitis [12,17].

A new approach is to associated the MRI or CT with lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, in infection diverticulitis cases [18,19].

The present study intended to assess the feasibility of such an approach. The 24 patients included are indeed a small number of patients (which is one of the limitations of this study), but help in drawing a preliminary picture that could eventually lead the way for further, ideally multicentric prospective studies.

MRI’s superiority over CECT and US, in achieving higher soft tissue resolutions is a well-known fact [12,20,21,22]. This is one of the advantages that could recommend the use of MRI in selected acute diverticulitis settings. Both MRI and CECT clearly identify and delineate pericolic fat and mesenteric oedema/stranding/infiltration, inflammatory colic wall thickening, stenosis and the presence of diverticula [12,20,21,22,23]. Similar imaging findings concerning acute abscess formation and chronic internal fistulas are offered by both CECT and MRI, with somehow better sensitivity and specificity leaning towards MRI’s capacity in detecting lower situated fistulas communicating to the pelvic organs, another advantage of being a non-ionizing imaging method [20,23]. Concerning MRI’s sensitivity and specificity towards the early diagnosis of potential complicated acute sigmoid diverticulitis, as previously mentioned, few and inconsistent data emerge from small sampled prospective studies or case reports. Sensitivity rates range from 86% to 96%, with some studies reporting even 100% rates in smaller, truly homogenous cohorts of patients [12,20,22,23,24,25]. Similar values have been reported by the same studies for the specificity rates, ranging from 88% to 92%.

Until recent times, the favored non-contrast-enhanced MRI sequence usually used for the diagnosis of acute sigmoid diverticulitis or any other scenarios of acute abdomen, when CECT was no indicated, was that of T2 Half Fourier Acquisition Single Shot Turbo Spin Echo (HASTE) [20,26]. In their prospective study, Byott and Harris [26], subjectively concluded that the T2 HASTE sequence reduces motion artifacts, offering better soft tissue differentiation details for the examiner (diverticula identification, free/moving air or stenosis). Inflammation, oedema or fluid (stages of the natural history of acute sigmoid diverticulitis) have also been identified using T2-fat suppression sequences, without any improved specificity or sensitivity rates, when compared to CECT, but with significant additional financial costs [24,27]. Not the same can be stated when trying to compare the accuracy of differentiating between acute diverticulitis and inflammatory sigmoid cancer when comparing CECT to non-contrasted enhanced MRI sequences, but small cohort studies show promising results [28,29].

On the other hand, the balance shifts towards Gadolinium contrast-enhanced MRI, which offers better sensitivity and specificity rates (versus CECT) in detecting true bowel thickness and mesocolon fat stranding, firstly due to the better migration of Gadolinium towards the interstice [20,25,30]. This principle of an “early arterial-early interstitial” passage while using Gadolinium-is the keystone towards differentiating between acute sigmoid colon diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel diseases (such as Crohn’s of ulcerative colitis), colon epiploic appendicitis, ischemic colitis and cancer [20,27,31].

Using MRI-colonography, does somehow aid towards a more suggestive diagnosis of sigmoid colon cancer, especially in the inflammatory setting, when compared to CECT, but this type of imaging seems to lack identification rates when non-inflammatory smaller than 5 mm lesions exist concomitant to an acute episode of diverticulitis [20,25,31].

To our best knowledge, the only reported small cohort study favoring the extensive use of non-contrast-enhanced MRI (via concomitant image acquisition in the T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging—DWI sequences) in the acute sigmoid diverticulitis setting, is that of Öistämö et al. [12]. The accuracy in differentiating between a pseudotumoral acute sigmoid colon diverticulitis and an inflammatory sigmoid colon cancer was associated with a sensitivity and specificity rate of 100%. Their pilot preliminary study included only a limited number of patients and that consists of one of the major limitations and drawbacks of their report. It is a known fact that DWI protocols are widely used for the diagnostic of other digestive neoplasms, owing their hyperintense signals depicted on the MRI scans, to the Brownian movement of water molecules within the bowel wall [12].

This pathophysiologic background to the acquired images is caused either by oedema, inflammation or abscess formation (as in the case of acute diverticulitis) or restricted diffusion (as in the case of tumor fibrosis) [12,32]. One of the major drawbacks and patient-dependent factors that influence the DWI sequence images are movement artifacts, which can be reduced with a longer image acquisition time [33].

MRI was suspicious for neoplastic sigmoid pathology in three cases, namely 15% of the total. In two of these cases, an invasive tumor pathology was confirmed by histological analysis. In one case, although histology did not provide evidence, the abdominopelvic CT and several colonoscopies, inclined towards a strong suspicion of an expansive malignant process. MRI was the only preoperative examination that suggested otherwise. The pain-killer treatment, including opioids may interfere with the MRI [34,35].

Although this aspect was not the main purpose of the study, this could indicate that MRI examination is useful to guide practitioners in doubtful cases. However, this assertion is absolutely indicative and hypothetical, especially when you consider that in the same study, it was possible to assess a woman of 68 years, with a typical presentation suggesting diverticulitis, with two imaging tests consistent for high suspicion of neoplastic involvement. The results of the scan and resonance were excluded by colonoscopy with leveled biopsies. The analysis of these preliminary results does not support nor contrast the systematic use of MRI to evaluate all diverticulitis diagnosed by CT. The difference between this study and the study published by Öistämö et al. [12] is that the present study had assessed the ability of MRI compared to CECT to recognize a neoplastic disease of the sigmoid, where the diagnosis had already been made with certainty. The approach of the Swedish author was, thus, different. Regarding the study in our institution, the poor results found seem to be discouraging and do not favor a systematic use of MRI in such a context, but these results could be linked to the small number of patients included in the study. Major drawbacks for the completion of this study were represented by the patient recruitment phase, bearing in mind the fact that recruitment was made only from among the patients admitted in the Visceral Surgery Department. Furthermore, the logistical obstacle related to the ease of access to the MRI exam in our service, could be considered as another disadvantage in the small number of patients enrolled versus the patients lost, that were subjected to such examination in other services. An extension of this study to a multicentric prospective evaluation of similar situations should be taken into account.

Conclusions

Taking into consideration the fact that current studies in the literature that identify MRI as a useful tool for the extension-balance in the management of colon-rectal cancer, and for the fact that the interest shown for MRI in distinguishing sigmoid cancer from pure inflammation, MRI seems to be an examination method whose potential has not yet been sufficiently explored in this context. Early diagnosis of these types of cancer, presenting with an inflammatory aspect, unusual and confusing, is fundamental for the early management, in order to start an adapted therapy at the correct time.

One can state that the frequency and the incidence of sigmoid cancer mimicking an indefinite or diverticular sigmoiditis are not high. The findings of this study, which evaluates only 24 patients, could push forward the definitive and systematic use of MRI as a complementary examination in the assessment of acute diverticulitis. However, the advantages that early diagnosis could bring to patients with rare inflammatory tumors, indicate a need in improving the date related to this subject. A study including a larger number of patients would be preferable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.C.; methodology, I.M.M.; software, C.M.; validation, O.L.P., C.D.C.; formal analysis, M.A.M.; investigation, T.G.A., A.V.P.; resources, M.S.M.; data curation, S.N.R., T.G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.M.; writing—review and editing, C.D.C., M.S.M.; visualization, A.V.P., H.M.S.; supervision, C.D.C.; project administration, O.L.P.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no known conflicts of interest in the publication of this article. The manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

References

- O’Donnell, E.K. Early Cancer Detection in Focus. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2024, 38, xi–xii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anania, G.; Vedana, L.; Santini, M.; et al. Complications of diverticular disease: surgical laparoscopic treatment. G Chir. 2014, 35, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.; Davies, M.; Wolff, B.; et al. Complicated diverticulitis: is it time to rethink the rules? Ann Surg. 2005, 242, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.R.; Dozois, E.J.; Wolff, B.G.; Gullerud, R.E.; Larson, D.R. Diverticulitis: a progressive disease? Do multiple recurrences predict less favorable outcomes? Ann Surg. 2006, 243, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barret, M.; Abbes, L.; Zinzindohoué, F. Suivi et conseils diét6téques dans la diverticulose colique et ses complications [Follow-up and dietary advice after sigmoid diverticulitis]. Rev Prat. 2013, 63, 830–833. [Google Scholar]

- Slama, J.L. La diverticulose colique et ses complications [Colonic diverticulosis and its complications]. Soins. 1981, 26, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fozard, J.B.; Armitage, N.C.; Schofield, J.B.; Jones, O.M.; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. ACPGBI position statement on elective resection for diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011, 13 (Suppl 3), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, M.; Prathiraja, O.; Caldera, D.; et al. Colon Cancer Screening Methods: 2023 Update. Cureus. 2023, 15, e37509, Published 2023 Apr 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, M.J. Imaging of colonic diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004, 17, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, H.; Huh, S.J.; Oh, D.; Jeong, B.K.; Ju, S.G. Radiation sigmoiditis mimicking sigmoid colon cancer after radiation therapy for cervical cancer: the implications of three-dimensional image-based brachytherapy planning. J Gynecol Oncol. 2012, 23, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Öistämö, E.; Hjern, F.; Blomqvist, L.; Von Heijne, A.; Abraham-Nordling, M. Cancer and diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon. Differentiation with computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging: preliminary experiences. Acta Radiol. 2013, 54, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, O.; Geoghegan, T.; McAuley, G.; Persaud, T.; Khosa, F.; Torreggiani, W.C. Pictorial review: magnetic resonance imaging of colonic diverticulitis. Eur Radiol. 2007, 17, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.M.; Strate, L.L. Acute Colonic Diverticulitis. Ann Intern Med. 2018, 168, ITC65–ITC80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regenet, N.; Tuech, J.J.; Pessaux, P.; et al. Intraoperative colonic lavage with primary anastomosis vs. Hartmann’s procedure for perforated diverticular disease of the colon: a consecutive study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002, 49, 664–667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shafi, S.; Priest, E.L.; Crandall, M.L.; et al. Multicenter validation of American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grading system for acute colonic diverticulitis and its use for emergency general surgery quality improvement program. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016, 80, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heverhagen, J.T.; Sitter, H.; Zielke, A.; Klose, K.J. Prospective evaluation of the value of magnetic resonance imaging in suspected acute sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008, 51, 1810–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, V.D.; Silaghi, A.; Epistatu, D.; Dumitriu, A.S.; Paunica, S.; Bălan, D.G.; Socea, B. Diagnosis and management of colon cancer patients presenting in advanced stages of complications. J Mind Med Sci. 2023, 10, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reil, P.M.; Maghiar, T.T.; Vîlceanu, N.; et al. Assessing the Role of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Receptor (CD14) in Septic Cardiomyopathy: The Value of Immunohistochemical Diagnostics. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022, 12, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerjen, F.; Zaidi, T.; Chan, S.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the diagnosis and management of acute colonic diverticulitis: a review of current and future use. J Med Radiat Sci. 2021, 68, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreyer, A.G.; Fürst, A.; Agha, A.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging based colonography for diagnosis and assessment of diverticulosis and diverticulitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004, 19, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heverhagen, J.T.; Zielke, A.; Ishaque, N.; Bohrer, T.; El-Sheik, M.; Klose, K.J. Acute colonic diverticulitis: visualization in magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001, 19, 1275–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stidham, R.W.; Higgins, P.D. Imaging of intestinal fibrosis: current challenges and future methods. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016, 4, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaghi, A.; Constantin, V.D.; Socea, B.; Banu, P.; Sandu, V.; Andronache, L.F.; Dumitriu, A.S.; Paunica, S. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis, diagnosis and current therapeutic approach. J Mind Med Sci. 2022, 9, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaj, W.; Ruehm, S.G.; Lauenstein, T.; et al. Dark-lumen magnetic resonance colonography in patients with suspected sigmoid diverticulitis: a feasibility study. Eur Radiol. 2005, 15, 2316–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byott, S.; Harris, I. Rapid acquisition axial and coronal T2 HASTE MR in the evaluation of acute abdominal pain. Eur J Radiol. 2016, 85, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavel, F.M.; Vesa, C.M.; Gheorghe, G.; et al. Highlighting the Relevance of Gut Microbiota Manipulation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11, 1090, Published 2021 Jun 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, C.; Rothenbacher, T.; Rospleszcz, S.; et al. Characteristics and associated risk factors of diverticular disease assessed by magnetic resonance imaging in subjects from a Western general population. Eur Radiol. 2019, 29, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadhar, K.; Kielar, A.; Dighe, M.K.; et al. Multimodality approach for imaging of non-traumatic acute abdominal emergencies. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016, 41, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crownover, B.K.; Bepko, J.L. Appropriate and safe use of diagnostic imaging. Am Fam Physician. 2013, 87, 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Destigter, K.K.; Keating, D.P. Imaging update: acute colonic diverticulitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009, 22, 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malayeri, A.A.; El Khouli, R.H.; Zaheer, A.; et al. Principles and applications of diffusion-weighted imaging in cancer detection, staging, and treatment follow-up. Radiographics. 2011, 31, 1773–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serai, S.D.; Hu, H.H.; Ahmad, R.; et al. Newly Developed Methods for Reducing Motion Artifacts in Pediatric Abdominal MRI: Tips and Pearls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020, 214, 1042–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savlovschi, C.; Serban, D.; Trotea, T.; Borcan, R.; Dumitrescu, D. Post-surgery morbidity and mortality in colorectal cancer in elderly subjects. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013, 108, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meșină, C.; Dumitrescu, T.V.; Ciorbagiu, M.C.; Obleaga, C.V.; Vilcea, I.D.; Mesina-Botoran, M.I. Colonic diverticulosis—diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties. J Mind Med Sci. 2022, 9, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2024 by the authors. 2024 Cornel Dragos Cheregi, Teodora Gabriela Alexescu, Andrei Vasile Pascalau, Ovidiu Laurean Pop, Calin Magheru, Ioana Maria Muresan, Nicoleta Ramona Suciu, Maur Sebastian Horgos, Mihai Stefan Muresan.