Introduction

The differential diagnosis of the neck nodule in adult patients is sometimes difficult for the doctor to establish, as it is necessary to distinguish between different clinical forms, three of which are more commonly encountered: congenital lesions (usually rare), inflammatory tumors (enlarged lymph nodes from infectious or noninfectious diseases) and neoplastic (benign or malign) masses. If synchronous cervical tumors are identified, multiple imaging and laboratory tests are required.

Schwannomas (also called neurilemomas) are nerve sheath tumors developed from Schwann cells. Most often they are benign lesions, originating either from peripheral, cranial or autonomic nerves [

1]. A pathologic variant called melanotic schwannoma can become malignant [

2,

3]. Schwannomas grow in an eccentric fashion with the nerve itself being usually incorporated into the tumor capsule. This feature allows to differentiate them from neurofibromas.

Cervical schwannomas may develop from the last four cranial nerves (vagus nerve being the most common site) or from autonomic nerves - cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma (CSCS). They are slow-growing, well-delineated, non-pulsating and painless lesions, found incidentally on routine clinical examination. Sometimes cervical schwannomas are large, causing neck deformity or complaints like Horner`s syndrome, hoarse voice, dysphagia or aspiration pneumonia [

4,

5,

6].

Imaging studies - ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or angiography, are required for schwannoma diagnosis. Cervical ultrasound may detect splaying of the carotid bifurcation (suggesting CSCS) or separation of the internal jugular vein (IJV) and common carotid artery (CCA), indicating vagal schwannoma. Ultrasound also can detect the vagus nerve being distinct on the surface of the tumor, suggesting that the origin of schwannoma is the cervical sympathetic chain [

7]. Schwannomas are hypo or isoattenuated to skeletal muscle on CT scan. On MRI, a medium intensity signal on T1-weighted scan and an intense inhomogeneous enhancement on T2-weighted scan indicate schwannoma. The majority of lesions exhibit a uniform contrast enhancement with a peripheral rim of low intensity (corresponding to tumor capsule).

Surgical excision of the tumor (with sacrifice of a part of the cervical sympathetic chain) is the main therapeutic option for CSCS. Tumor enucleation represents an option, but is associated with a high risk of diffuse intraoperative bleeding from the inner surface of tumor capsule, which can be difficult to control [

8]. Postoperative complications include Horner`s syndrome, Pourfour du Petit syndrome (due to hyperstimulation of the cervical sympathetic chain) and first-bite syndrome. Permanent Horner`s syndrome indicates cutting of cervical sympathetic chain. A temporary Horner`s syndrome may also appear after intracapsular enucleation. The first-bite syndrome (development of debilitating chronic pain in the ipsilateral parotid region after the first few bites of food) is the result of damage of parotid gland sympathetic nerves [

9].

We report a case of a female patient diagnosed with synchronous CSCS, parathyroid adenoma and hypo-functional nodular goiter. To our knowledge, this is only the second case report publishing simultaneous CSCS and parathyroid adenoma (without nodular goiter) [

10].

Case Presentation

A 66 years-old female patient, previously diagnosed with hypofunctional nodular goiter (solitary nodule within the left thyroid lobe), was admitted for surgical removal of a right cervical extra thyroid mass, detected by cervical ultrasound during follow-up of thyroid disease. History-taking revealed no hoarseness, pain, fever, dysphagia, syncopal attacks or trauma. The patient denied smoking or alcohol consumption. She underwent a right knee replacement surgery one year after a septic knee arthritis, produced by Meticillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). She is taking 50 micrograms of L-Thyroxine daily. The clinical examination showed an obese patient (body mass index of 37.97 kg/m2) with two cervical lumps. The first tumor, located in the anterior neck triangle to the left of the midline, was a 2 cm well-delineated, soft and painless mass that was moving up with deglutition. The second one was a well-delineated, elastic and painless 4/3 cm mass, placed medially to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle and behind the IJV and CCA, not having pulsatility or mobility during deglutition. We did not find any other lumps in the cervical, supraclavicular or subclavicular areas.

The blood tests showed an elevated thyrotropin (TSH) level (6.73 microunits/l). The thyroperoxidase (TPO) antibodies value were within the normal range (5.71 units/ml). We also found an elevated parathormone (PTH) level (114.7 pg/ml) with a normal ionized calcium and a hypertriglyceridemia (273 mg/dl). The kidney function tests and vitamin D level were within normal range.

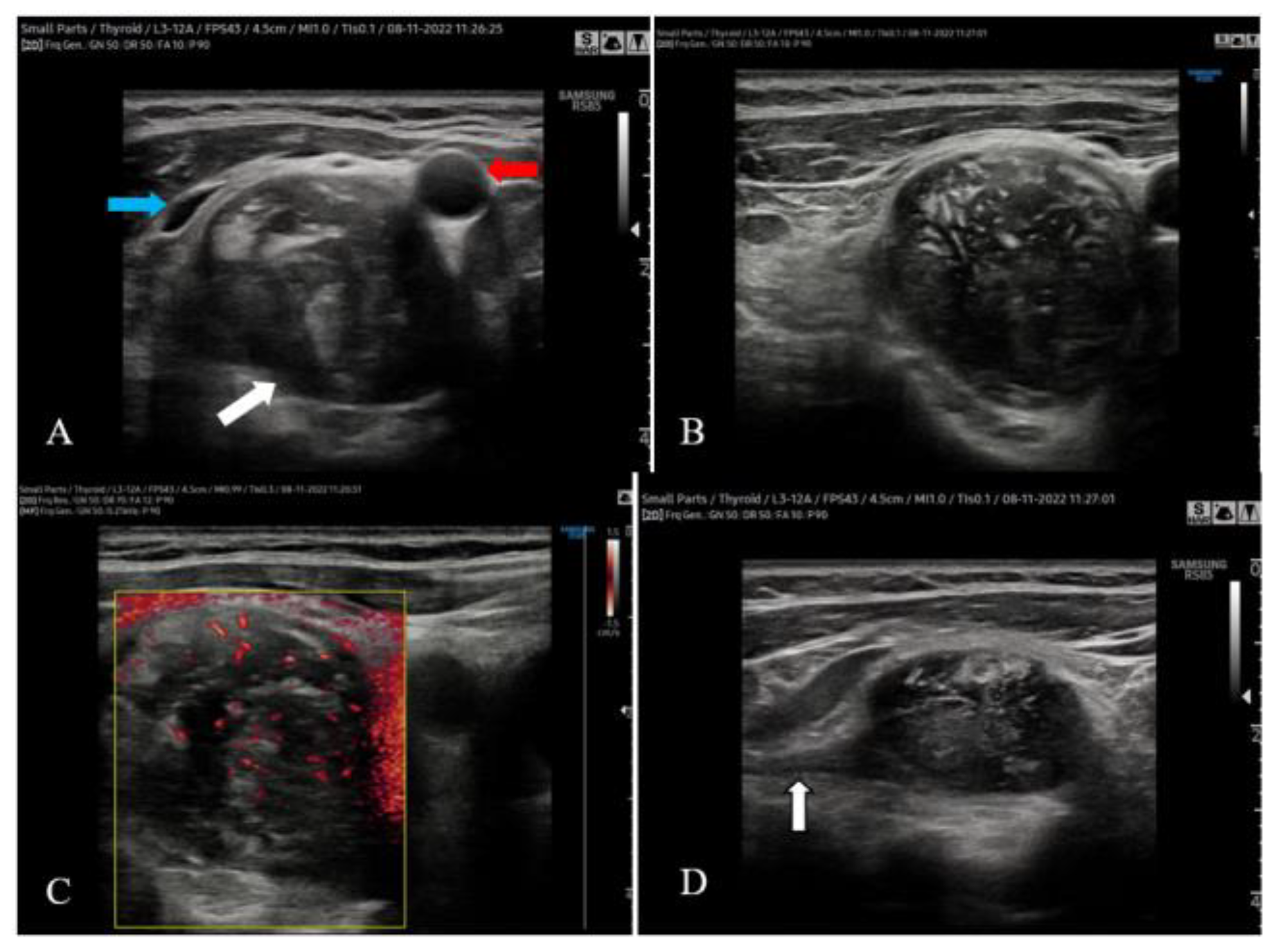

The cervical ultrasound confirmed the presence of a 20/16 mm inhomogeneous nodule within the left thyroid lobe with anechoic areas inside and peripheral blood vessels on color Doppler ultrasound. We did not detect nodules within the isthmus and right thyroid lobe. The 41/31/27 mm right cervical mass was located posteriorly and below the right thyroid lobe, being distinct from it. It pushed forward the right CCA and IJV, splaying them (

Figure 1A). The mass was inhomogeneous and showed central and peripheral blood vessels on color Doppler ultrasound (

Figure 1B,C). A hypoechoic linear structure seemed to be incorporated into the tumor in an eccentric fashion (

Figure 1D).

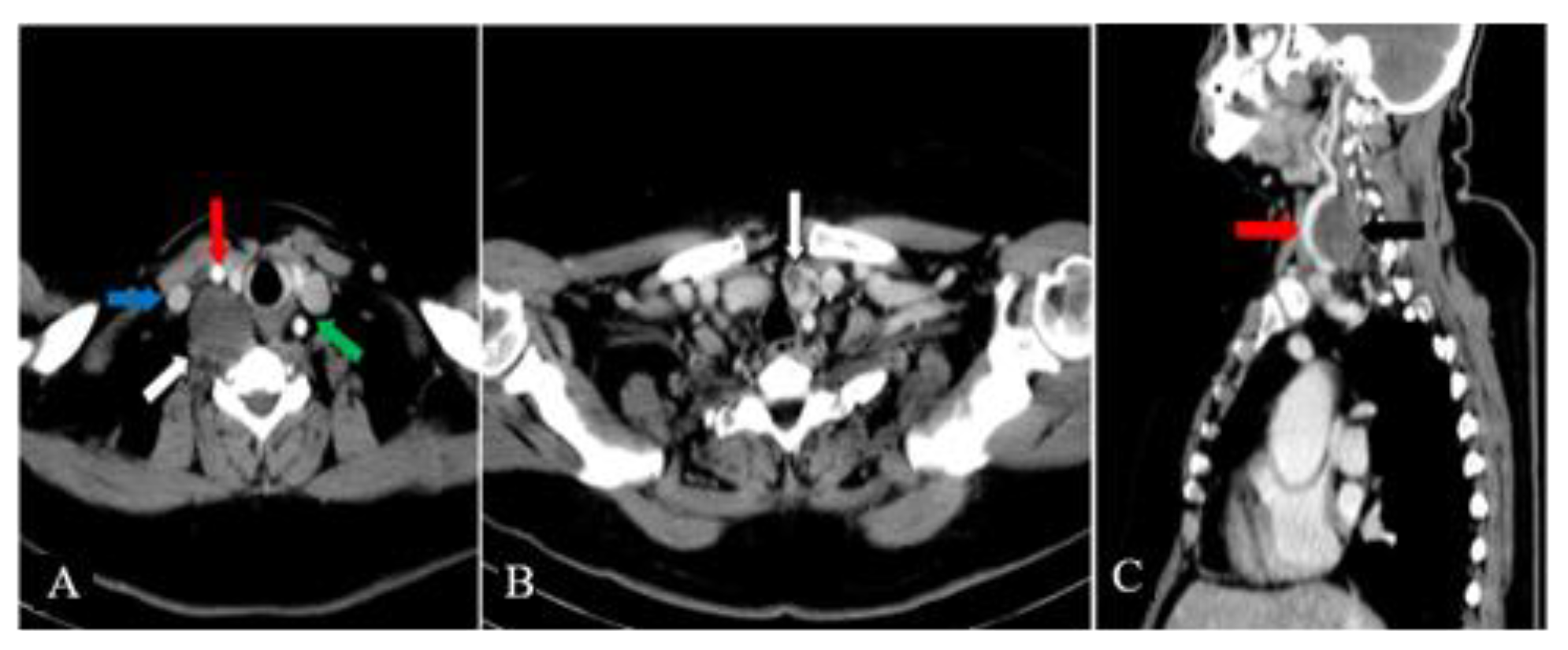

The contrast-enhanced cervical and chest CT scan showed that the mass was located in the right parapharyngeal space and had a heterogeneous structure with a weak contrast-enhancement (

Figure 2A). A hypoechoic nodule was confirmed within the left thyroid lobe, measuring 17 mm in diameter (

Figure 2B). The right CCA was making a 360 degrees loop in its proximal part, but did not show wall abnormalities and was patent (

Figure 2C). The CT scan did not detect other cervical masses or enlarged cervical, submental or submandibular lymph nodes.

The indirect laryngoscopy showed the mobility of both vocal cords. MRI was not performed because the patient previously underwent a right knee replacement surgery using a cemented Triathlon-Stryker prosthesis. A Sestamibi parathyroid scan could help detect the overactive parathyroid gland (including an ectopic one), but this study was not performed. We decided to explore all the parathyroid glands during the surgical procedure in order to detect the cause of primary hyperparathyroidism.

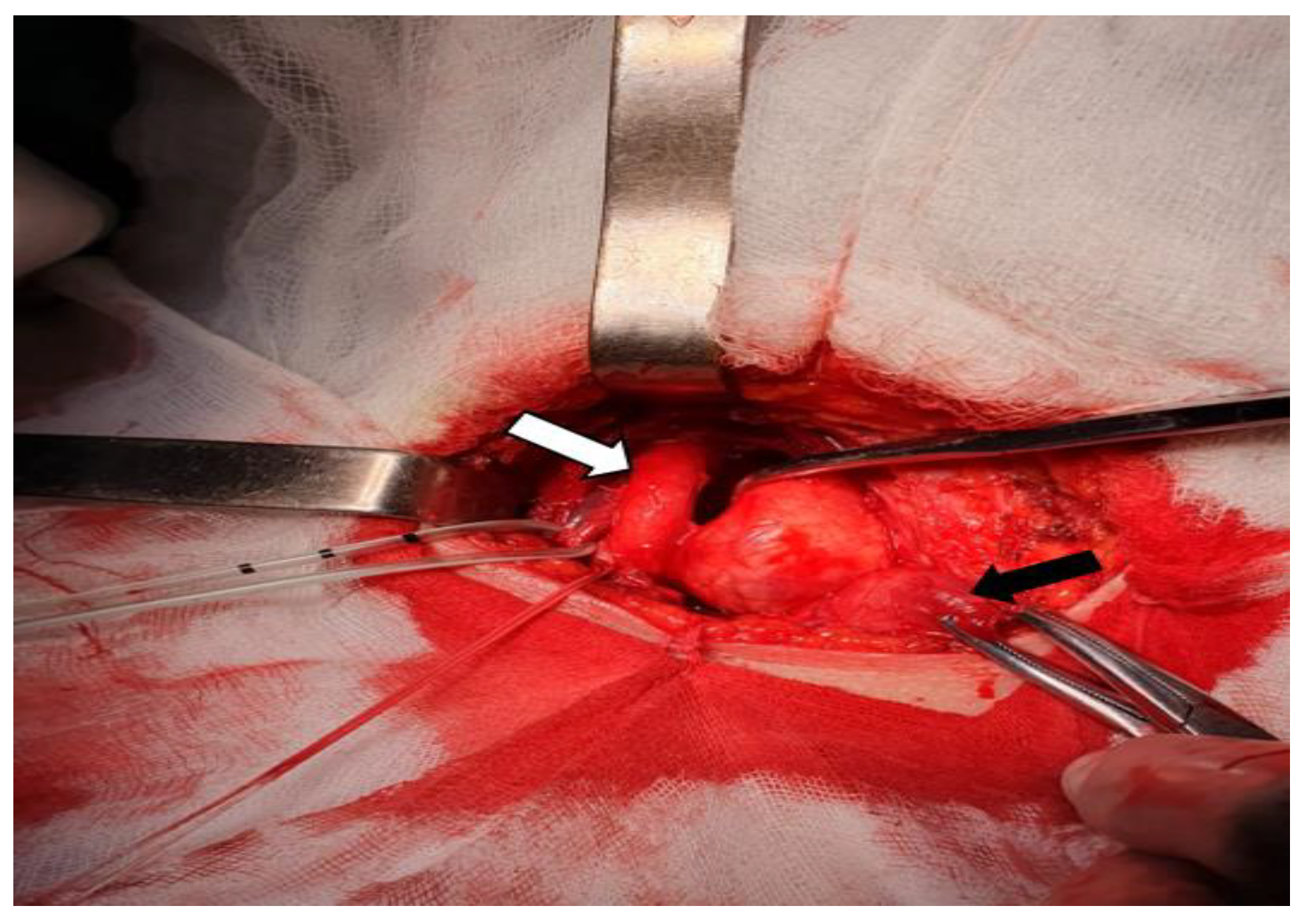

Having a preoperative diagnosis of nerve originating right cervical tumor, hypofunctional nodular goiter and primary hyperparathyroidism, the surgical procedure was performed under general anesthesia using a Kocher`s cervical incision. We confirmed the left lobe nodular goiter; we did not detect nodules in the isthmus or the right thyroid lobe. Behind the left thyroid lobe, we also identified an enlarged (10/5/5 mm) left inferior parathyroid gland. We explored the other parathyroid glands and these were normal. The right parapharyngeal mass was encapsulated, yellow-whitish and elastic. It was placed posteriorly and laterally to the right thyroid lobe and trachea. The tumor displaced forward and splayed the right CCA and IJV. The vagus nerve (also displaced laterally by the tumor) was dissected, being distinct of it (

Figure 3).

We performed surgical excision of the right cervical mass, total thyroidectomy and removal of the enlarged left inferior parathyroid gland. A postoperative right upper eyelid ptosis appeared, indicative for Horner`s syndrome. No hoarseness, swallowing difficulties, Pourfour du Petit or first-bite syndrome occurred postoperatively.

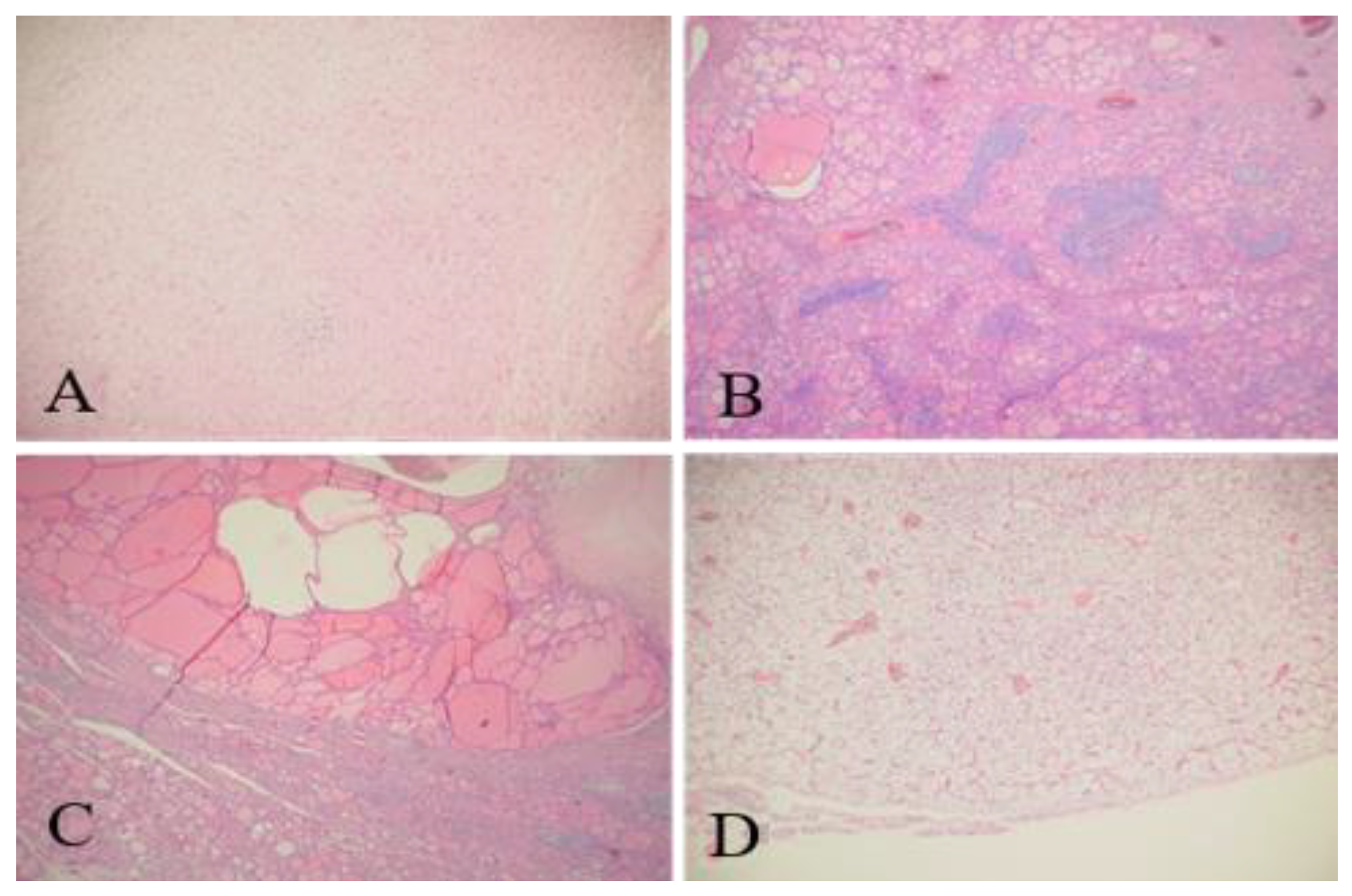

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed that the right cervical tumor could be a schwannoma (neurilemoma) (

Figure 4A). Because Verocay bodies were absent on microscopic sections, the pathologist recommended immunohistochemical staining to be performed. The thyroid tissue had features of nonspecific chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and nodular goiter (

Figure 4B,C). The removed parathyroid gland had an adenoma (

Figure 4D).

The immunohistochemical staining were diffusely positive for S100 protein, peripherally positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and negative for CD34 protein, thus confirming the schwannoma diagnosis; the Ki67 index was 1%.

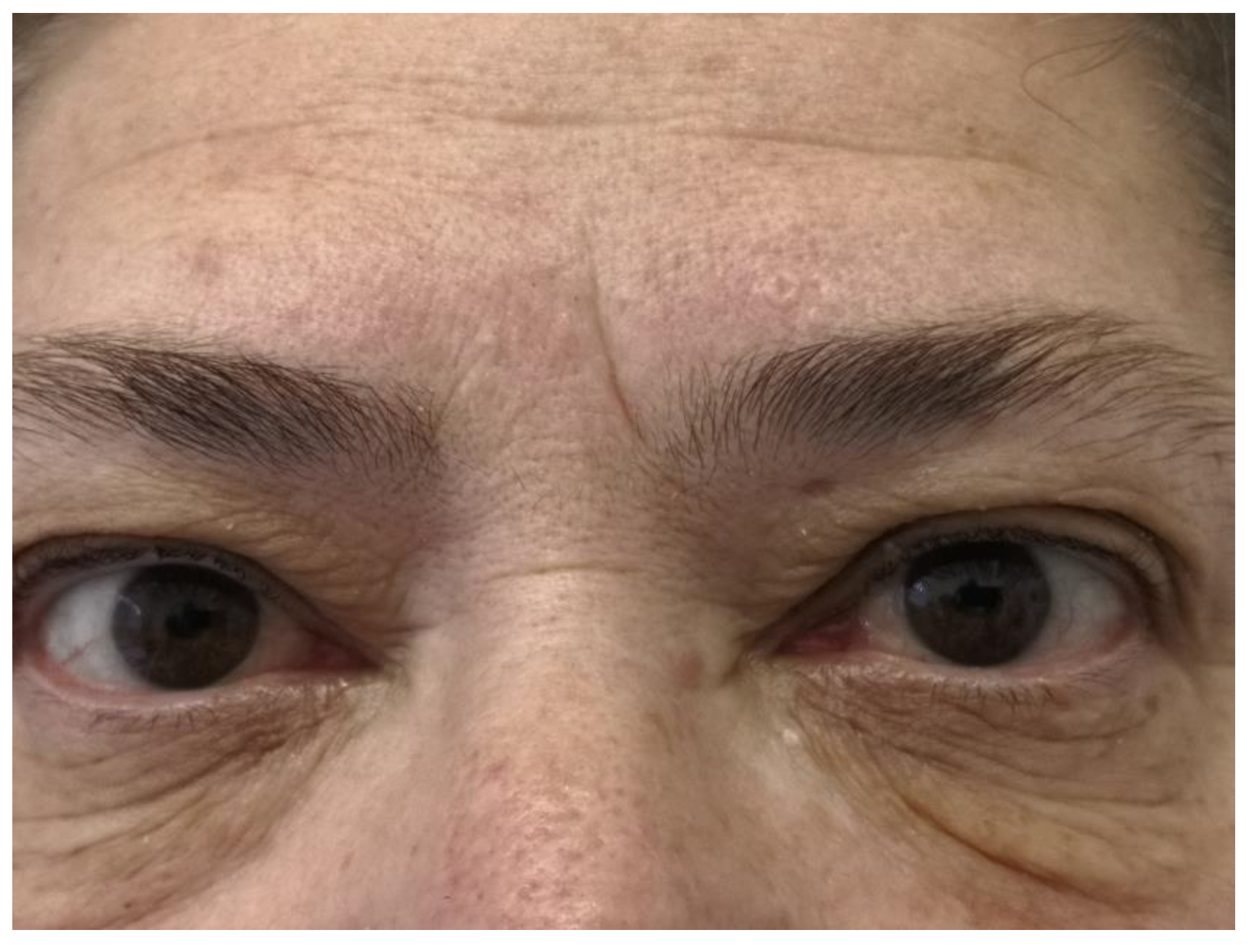

The postoperative PTH level was normal (44 pg/ml). The patient underwent thyroid hormone replacement therapy with endocrinological follow-up. The follow-up at 6 months did not detect a tumor recurrence. A barely visible right upper eyelid ptosis was noted (

Figure 5).

Discussions

Schwannomas are benign tumors arising from the nerve sheath of peripheral, cranial, sensory, motor or sympathetic nerves within the head, neck, upper and lower extremities. 25-45% of extracranial schwannomas occur in the head and neck regions [

11]. CSCS are rare tumors, typically located within the parapharyngeal space or the retrostyloid compartment. They occur more frequently in 20 to 50 years old adults, without gender predominance [

12].

Usually, they are asymptomatic, solitary, nonplusing, slow-growing masses, as it was on our patient [

13]. Before the surgical procedure, we did not detect significant signs for vagus (hoarseness and vocal cord palsy) or sympathetic chain involvement (Horner's syndrome). When present, pulsation is an atypical feature of CSCS, being the consequence of carotid artery proximity or indicating tumor hypervascularity. This feature requires to differentiate CSCS from carotid body tumors [

14,

15].

The preoperative differential diagnosis is difficult and requires multiple imaging studies. It includes vagal schwannoma, enlarged lymph node, carotid body tumor and paraganglioma [

16].

Misdiagnosing CSCS as vagus nerve schwannoma on preoperative imaging studies is possible [

4,

17]. A course of vagus nerve on the tumor is an important element to detect a vagal origin of schwannoma, but is difficult to find by preoperative imaging studies. On preoperative cervical ultrasound we detected a hypoechoic cord-like structure entering into the deep aspect of the tumor in an eccentric fashion. This information raised our suspicion of a nerve originating lesion.

A mass on contrast-enhanced CT scan pushing forward the internal or common carotid artery is suggestive of vagal schwannoma or CSCS. The vagal schwannoma grows between the internal carotid artery (ICA) or CCA and IJV, causing separation of these structures. This feature is also observed in some CSCS (more often than reported), making the differential diagnosis difficult. Splaying of the ICA and IJV with medial ICA displacement indicates vagal schwannoma, while the absence of separation with lateral ICA displacement suggests CSCS [

18]; sympathetic chain schwannoma may also mimic a carotid body tumor [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In our patient, the contrast-enhanced CT scan identified a right parapharyngeal tumor that showed a weak contrast-enhancement. The mass pushed forward the CCA and IJV. The vessels were also separated by the tumor; this information, combined with the ultrasound report, made more difficult a preoperative differential diagnosis between vagal schwannoma and CSCS. Only during the surgical procedure, after dissecting the CCA, IJV and vagus nerve, we could rule out the vagal origin of the tumor.

An enlarged cervical lymph node (inflammatory or metastatic) could not be completely excluded preoperatively, but was thought to be less probable because we did not find any signs, laboratory or imaging data suggesting an inflammatory condition or a malignant tumor in the cervical or chest area.

The cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma also may mimic a carotid body tumor [

19,

20,

21,

22], splaying of the carotid bifurcation usually suggests a carotid body tumor, but also can be seen in some CSCS. The tumor vascularity is the main criterion to differentiate these two entities. Tumor hypervascularity indicates a carotid body tumor, whereas in patients without tumor hypervascularity, CSCS is the most probable diagnosis [

23,

24]. The vagus nerve schwannoma seldom widens the carotid bifurcation. The tumor described here was hypodense compared to the muscle and did not produce splaying of the carotid bifurcation.

We could not perform MRI because our patient had a right knee replacement surgery. But if it would have been possible, the gadolinium-enhanced MRI would have shown a low intensity signal on T1-weighted images with high intensity signal on T2-weighted images, suggesting schwannoma. As mentioned before, the main criterion to differentiate carotid body tumor and cervical schwannoma is the vascularity. The low-degree vascularity usually indicates a cervical schwannoma, but sometimes the tumor can exhibit a marked contrast enhancement on gadolinium MRI due to intratumoral hemorrhage and vasodilation [

19]. Paragangliomas are located more cranially in the neck region compared to schwannoma. They are isodense when compared to muscle on native CT scan and exhibit extremely bright contrast enhancement on MRI (a non-pathognomonic “salt and pepper” pattern, as may also be found in other hypervascular lesions) [

16].

The angiography is an invasive study used to reveal vascularity within tumor or around the capsule and also to differentiate CSCS from carotid body tumors. The schwannomas are hypovascular or moderately hypervascular tumors with tortuous vessels and puddling of contrast material [

25,

26]; we did not perform this imaging study.

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy and FNA cytology are useful for ruling out a lymph node pathology, but the tumor location and proximity of main neck vessels are making FNA biopsy difficult to perform. The FNA diagnostic value in case of schwannoma is quite low. FNA-cytology can lead to correct diagnosis in only 25% of cervical schwannomas [

11,

12].

We planned the surgical procedure with the intent to perform a tumor removal, combined with total thyroidectomy and exploration of parathyroid glands. Considering the ultrasound features of the thyroid nodule and the hypofunctional thyroid status (requiring hormonal supplementation therapy), we decided to remove the thyroid gland completely. Only after dissection of the right CCA, IJV and vagus nerve, we could rule out the vagal schwannoma diagnostic. An enlarged left inferior parathyroid gland was excised together with the cervical tumor and the thyroid gland.

The presence of Horner`s syndrome (ipsilateral pupillary miosis and ptosis, enophthalmos and facial anhydrosis) in patients with CSCS before surgery is unusual. This the most frequent complication after CSCS removal. It is an expected, but acceptable postoperative complication, because the tumor cannot be resected without sacrificing a portion of cervical sympathetic chain. [

13,

16,

19]. Incidence of Horner`s syndrome can be lowered by tumor intracapsular enucleation, but intraoperative bleeding (diffuse and difficult to control) and incomplete tumor excision are associated risks. In our patient, we confirmed the postoperative occurrence of Horner`s syndrome. At 6 months follow-up, the mild right upper eyelid ptosis was barely visible. Hoarseness, swallowing difficulty or jaw pain on mastication did not occur in the postoperative period.

The H&E staining confirmed the schwannoma diagnosis. It showed a mixed pattern - dense cellular areas (with elongated spindle-shaped cells having abundant eosinophylic cytoplasm and elongated oval or wavy-shaped nuclei) and hypocellular edematous areas; no mitoses or atypia were detected. This pattern represents Antony type A and B areas respectively. In some areas, nuclei produced vague palisade-forming clusters, but no Verocay bodies. The Verocay bodies are a required histopathological finding for diagnosing schwannomas. A Verocay body consists of two rows of elongated palisading nuclei that alternates with acellular zones made up of cytoplasmic processes of the Schwann cells. The absence of Verocay bodies on H&E staining required immunohistochemical staining in order to confirm the schwannoma diagnosis.

The immunohistochemical staining were diffusely positive for S100 protein, peripherally positive for EMA (expressed in perineural cells) and negative for CD34 protein; the Ki67 index was low (1%). The S100 protein immunostaining best differentiate schwannoma from neurofibroma. Strong and diffuse S100 positivity indicates schwannoma in contrast to neurofibroma, which variably expresses the antigen due to the presence of other cell populations.