Affective Temperaments and Personality Traits in Couple Well-Being

Abstract

Introduction

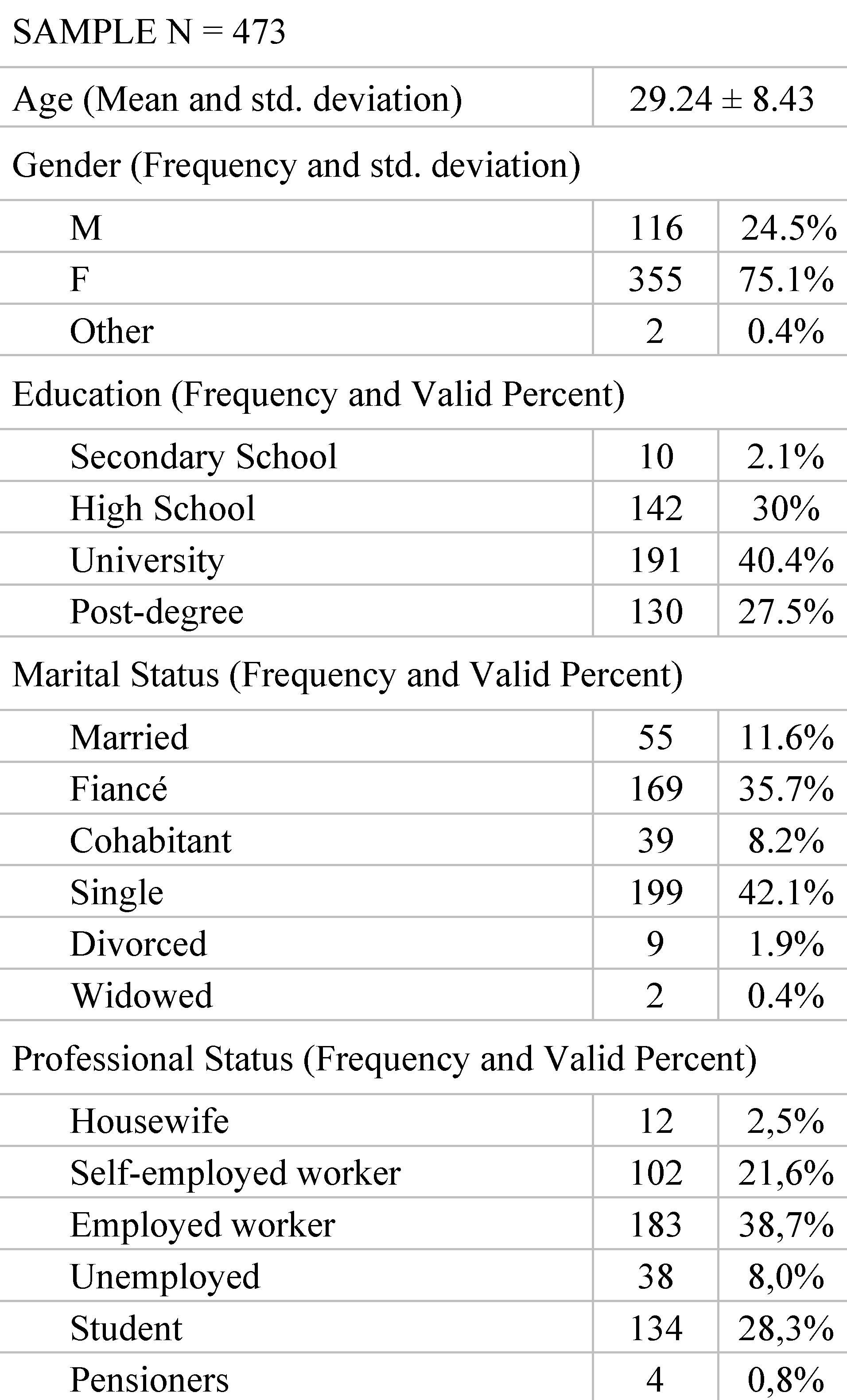

Materials and Methods

Measures

- Sociodemographic data, such as gender, age, marital status, schooling, occupation, origin, presence and possible number of children, and current involvement or not in a relationship.

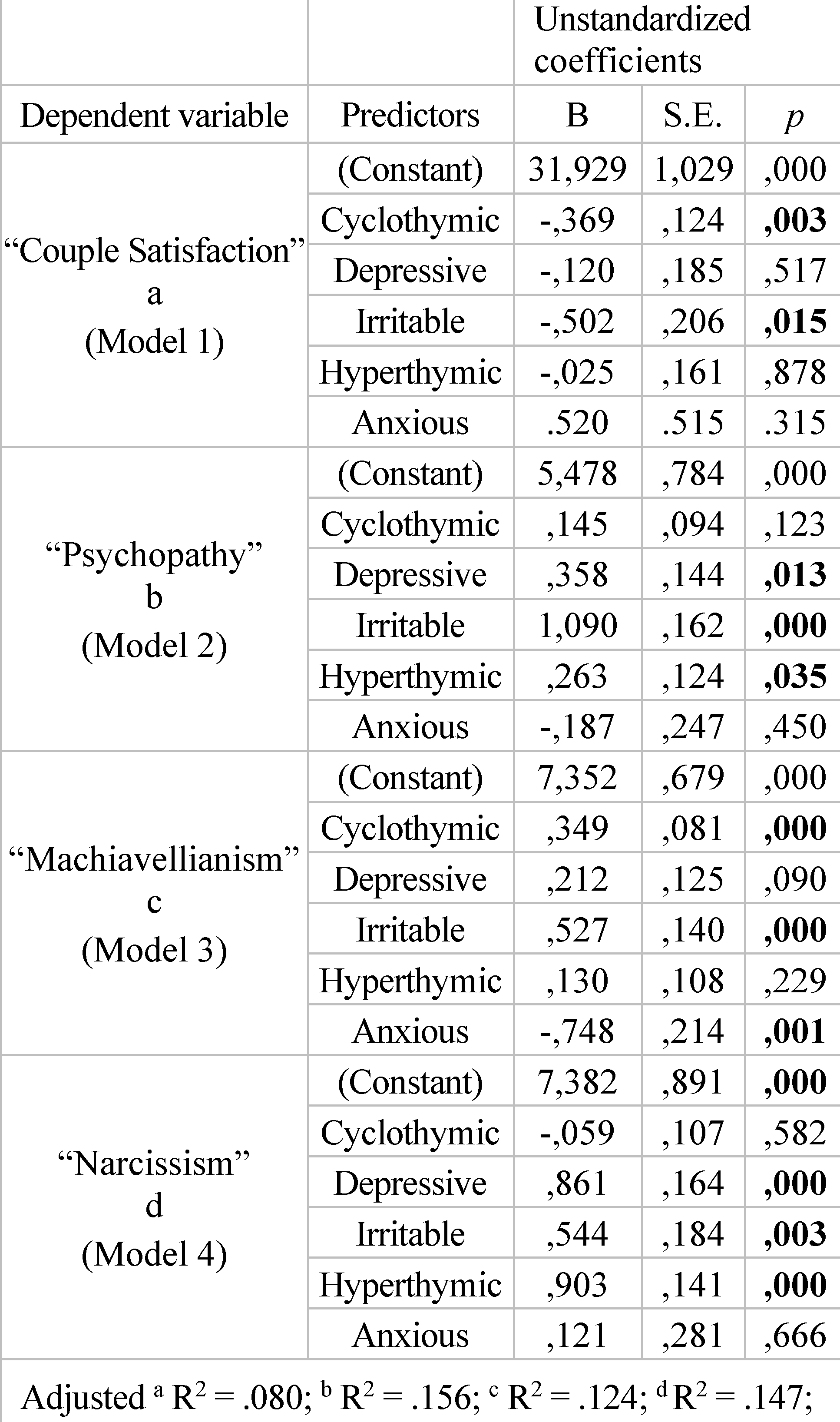

- Temperament Evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego—(TEMPS—A) Short version to assess affective temperaments [16]. The scale yields five affective temperament dimensions: cyclothymic, depressive, irritable, hyperthymic, and anxious. It is a self-report, yes-or-no type questionnaire (my way of being constantly oscillates between liveliness and indolence. Yes; No).

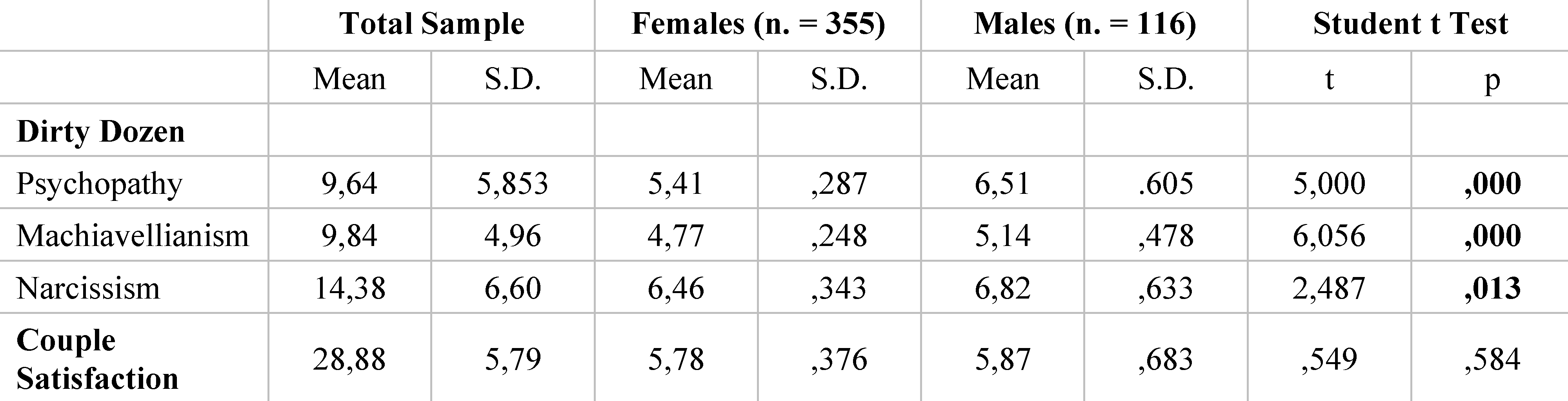

- The Dirty Dozen Italian Assessment [17,18] is a self-report characterized by 12 items, which aims to identify the general latent construct of the dark triad and the three traits related to it, namely Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism. Is rated the degree of agreement and disagreement (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) to statements such as, “I tend to manipulate others to get what I want” (Machiavellianism), or “I tend to lack remorse” (Psychopathy), or “I tend to want others to admire me” (Narcissism).

- The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) [19] is a questionnaire consisting of 7 items (Does your partner meet your needs) measured on a Likert scale from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). It was designed to measure overall relationship satisfaction, the higher the score, the greater the subject’s satisfaction within the relationship.

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussions

Limitations

Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mento, C.; Lombardo, C.; Whithorn, N.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Bruno, A.; Casablanca, M.; Silvestri, M.C. Psychological violence and manipulative behavior in couple: A focus on personality traits. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2023, 10, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.; Abell, L. Machiavellianism and sexual behavior: Motivations, deception and infidelity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 74, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petric, D. Gaslighting and the knot theory of mind. 2018. Medicine 2018, 29, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mento, C.; Spatari, G.; Muscatello, M.R.A. (Eds.) Gabbie di parole: Il linguaggio della violenza psicologica: Valutazione, pre-venzione e intervento; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2020; pp. 17–18. ISBN 9788835117971. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, P.R.; Garcia, L.P.; Maciel, E.L.N. The increase in domestic violence during the social isolation: What does it reveals? Rev. Bras. de Epidemiologia 2020, 23, e200033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keatley, D.A.; Quinn-Evans, L.; Joyce, T.; Richards, L. Behavior Sequence Analysis of Victims’ Accounts of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, NP19290–NP19309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, B.G.; Reinhard, M.-A. The Dark Triad and the PID-5 Maladaptive Personality Traits: Accuracy, Confidence and Response Bias in Judgments of Veracity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermer, J.A.; Jones, D.N. The behavioral genetics of the dark triad core versus unique trait components: A pilot study. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 154, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, I.; Moshagen, M.; Hilbig, B.E. Stability and Change: The Dark Factor of Personality Shapes Dark Traits. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2020, 12, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Mendlowicz, M.V.; Jean-Louis, G.; Rapaport, M.H.; Kelsoe, J.R.; Gillin, J.; Smith, T.L. TEMPS-A: Validation of a short version of a self-rated instrument designed to measure variations in temperament. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallini, S.; Alfani, A.; Marech, L.; Laghi, F. Unresolved attachment and agency in women victims of intimate partner violence: A case–control study. Psychol. Psychother. Theory, Res. Pr. 2016, 90, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asen, E.; Fonagy, P. Mentalizing Family Violence Part 1: Conceptual Framework. Fam. Process. 2016, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.E.; Azeredo, A.; Moreira, D.; Brandão, I.; Almeida, F. Personality characteristics of victims of intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 52, 101423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cale, E.M.; Lilienfeld, S.O. Sex differences in psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder. A review and integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 22, 1179–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santambrogio, J.; Colmegna, F.; Trotta, G.; Cavalleri, P.R.; Clerici, M. Intimate partner violence (IPV) e fattori associati: Una panoramica sulle evidenze epidemiologiche e qualitative in letteratura [Intimate partner violence (IPV) and associated factors: An overview of epidemiological and qualitative evidence in literature]. Riv. Psichiatr. 2019, 54, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, A.; Vellante, M.; Zucca, G.; Tondo, L.; Akiskal, K.; Akiskal, H. The Italian version of the validated short TEMPS-A: The temperament evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 120, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Webster, G.D. The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A.; Jonason, P.K.; Passanisi, A.; La Marca, L.; Di Dio, N.; Gervasi, A.M. Exploring the Dark Side of Personality: Emotional Awareness, Empathy, and the Dark Triad Traits in an Italian Sample. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 38, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, S.S. A Generic Measure of Relationship Satisfaction. J. Marriage Fam. 1988, 50, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heym, N.; Firth, J.; Kibowski, F.; Sumich, A.; Egan, V.; Bloxsom, C.A.J. Empathy at the Heart of Darkness: Empathy Deficits That Bind the Dark Triad and Those That Mediate Indirect Relational Aggression. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshagen, M.; Hilbig, B.E.; Zettler, I. The dark core of personality. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 125, 656–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.N.; Neria, A.L. The Dark Triad and dispositional aggression. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarev, A.; Phillips, A.R.; Hughes, D.J.; Irwing, P. Leader dark traits, workplace bullying, and employee depression: Exploring mediation and the role of the dark core. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Rudich, E.A.; Gregg, A.P.; Kumashiro, M.; Rusbult, C. Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horan, S.M.; Guinn, T.D.; Banghart, S. Understanding Relationships Among the Dark Triad Personality Profile and Romantic Partners’ Conflict Communication. Commun. Q. 2015, 63, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.A.; Brown, L.H.; Barrantes-Vidal, N.; Kwapil, T.R. The expression of affective temperaments in daily life. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 145, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tanaka, N.; Uji, M.; Hiramura, H.; Shikai, N.; Fujihara, S.; Kitamura, T. The role of personalities in the marital adjustment of Japanese couples. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2007, 35, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Hubbard, B.; Wiese, D. General Traits of Personality and Affectivity as Predictors of Satisfaction in Intimate Relationships: Evidence from Self- and Partner-Ratings. J. Pers. 2000, 68, 413–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collison, K.L.; South, S.; Vize, C.E.; Miller, J.D.; Lynam, D.R. Exploring Gender Differences in Machiavellianism Using a Measurement Invariance Approach. J. Pers. Assess. 2020, 103, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P.K.; Davis, M.D. A gender role view of the Dark Triad traits. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018, 125, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.F.; Ramos, C.L.; Willett, J.K. Psychopathy: Clinical features, developmental basis and therapeutic challenges. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Warren, J.; Burnette, M.L.; South, S.C.; Chauhan, P.; Bale, R.; Friend, R.; Van Patten, I. Psychopathy in women: Structural modeling and comorbidity. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2003, 26, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Book, A.S.; Starzyk, K.B.; Quinsey, V.L. The relationship between testosterone and aggression: A meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2001, 6, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, D.E.; Shirk, S.D.; Sloan, C.A.; Zeichner, A. Men who aggress against women: Effects of feminine gender role violation on physical aggression in hypermasculine men. Psychol. Men Masculinities 2009, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, E.; Newman, D.A.; Tay, L.; Donnellan, M.B.; Harms, P.D.; Robins, R.W.; Yan, T. Gender differences in narcissism: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 261–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Gidycz, C.A.; Murphy, M.J. College Women’s Stay/Leave Decisions in Abusive Dating Relationships: A Prospective Analysis of an Expanded Investment Model. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 26, 1446–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, G.; Kelly, B.D. Domestic violence against women and the COVID-19 pandemic: What is the role of psychiatry? Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2020, 71, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.B.; Miller, R.B.; Oka, M.; Henry, R.G. Gender Differences in Marital Satisfaction: A Meta-analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 2014, 76, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Stark, C. Gaslighting, Misogyny, and Psychological Oppression. Monist 2019, 102, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, P.L. The Sociology of Gaslighting. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

© 2024 by the author. 2024 Adrian Paul Suceveanu, Dragos Serban, Andreea Daniela Caloian, Georgeta Camelia Cozaru, Anca Chisoi, Anca Antonela Nicolau, Ioan Sergiu Micu, Andra Iulia Suceveanu

Share and Cite

Mento, C.; La Barbiera, C.; Silvestri, M.C.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Cedro, C.; Bruno, A.; Pandolfo, G.; Iannuzzo, F.; Lombardo, C. Affective Temperaments and Personality Traits in Couple Well-Being. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2024, 11, 183-188. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1467

Mento C, La Barbiera C, Silvestri MC, Muscatello MRA, Cedro C, Bruno A, Pandolfo G, Iannuzzo F, Lombardo C. Affective Temperaments and Personality Traits in Couple Well-Being. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2024; 11(1):183-188. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1467

Chicago/Turabian StyleMento, Carmela, Chiara La Barbiera, Maria Catena Silvestri, Maria Rosaria Anna Muscatello, Clemente Cedro, Antonio Bruno, Gianluca Pandolfo, Fiammetta Iannuzzo, and Clara Lombardo. 2024. "Affective Temperaments and Personality Traits in Couple Well-Being" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 11, no. 1: 183-188. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1467

APA StyleMento, C., La Barbiera, C., Silvestri, M. C., Muscatello, M. R. A., Cedro, C., Bruno, A., Pandolfo, G., Iannuzzo, F., & Lombardo, C. (2024). Affective Temperaments and Personality Traits in Couple Well-Being. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 11(1), 183-188. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1467