Syndrome or Symptoms? Assessing Cothymia, Neuroticism and Lifetime Comorbidity in a Sample of Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

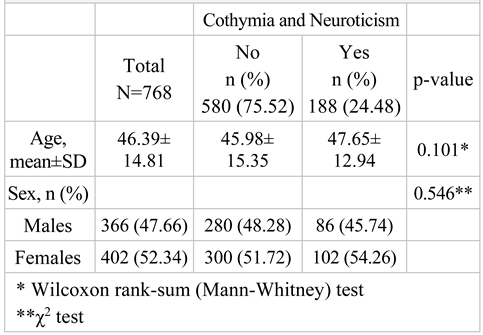

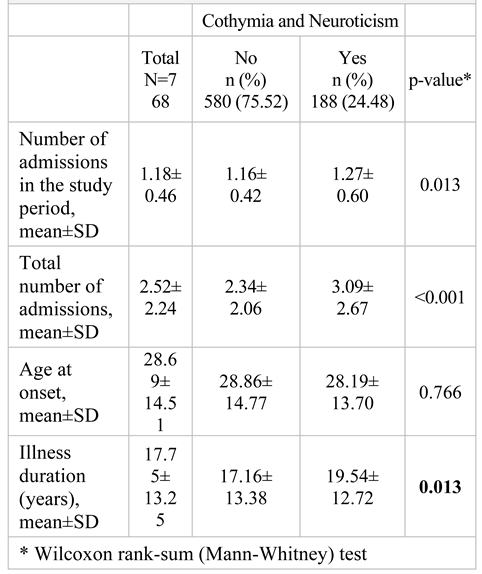

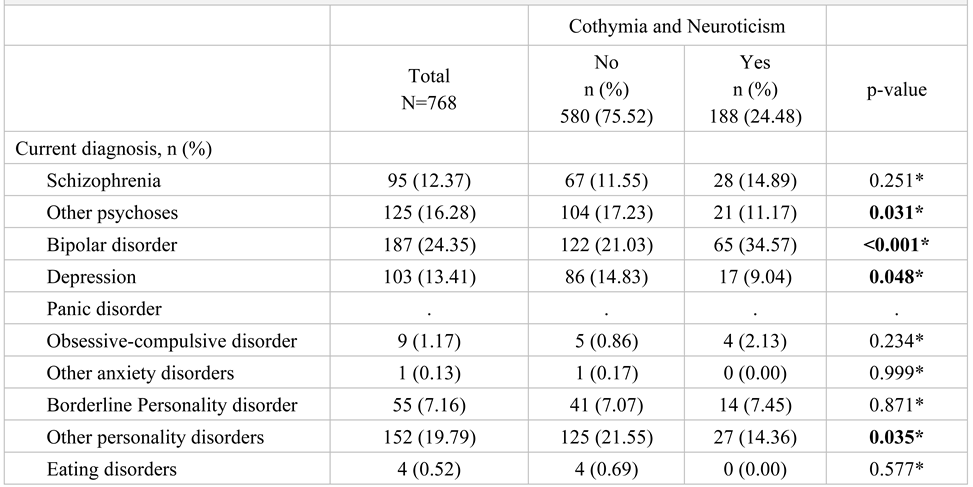

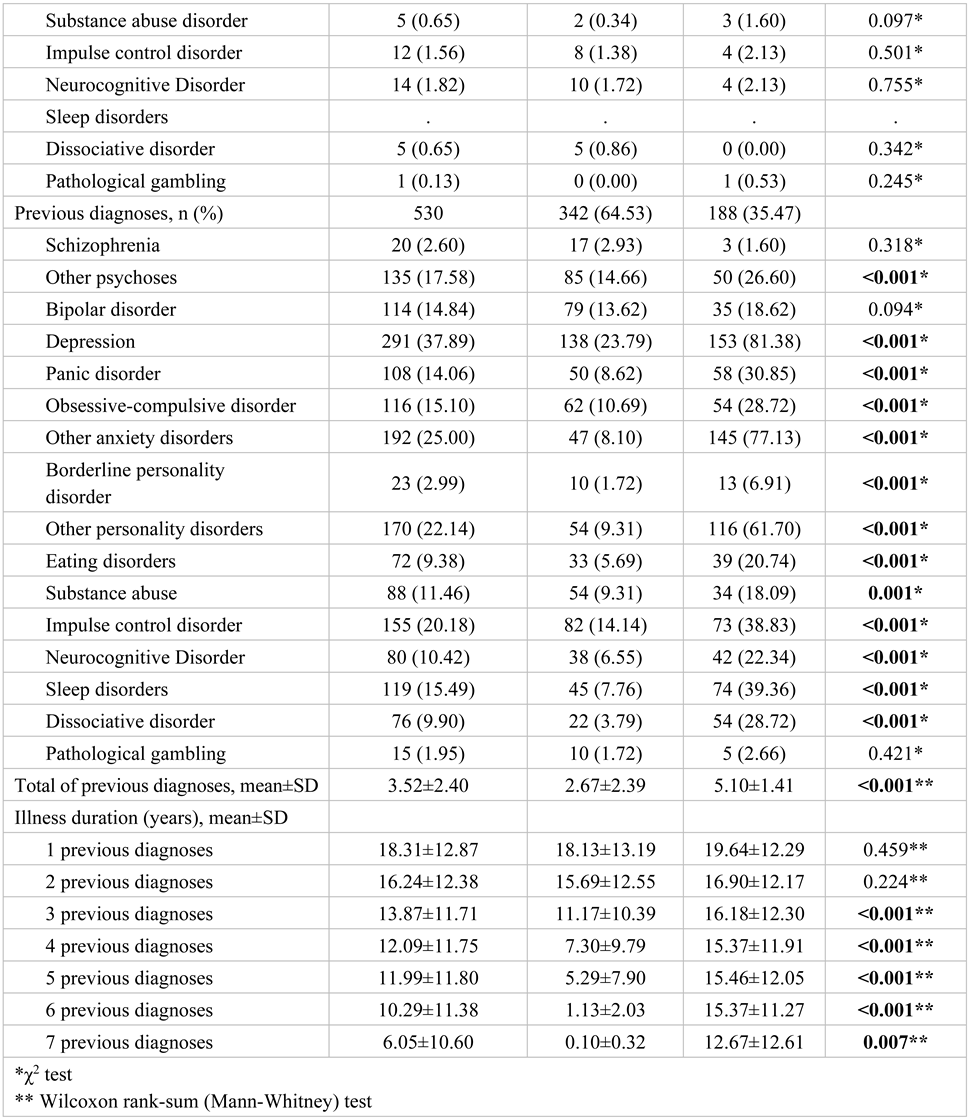

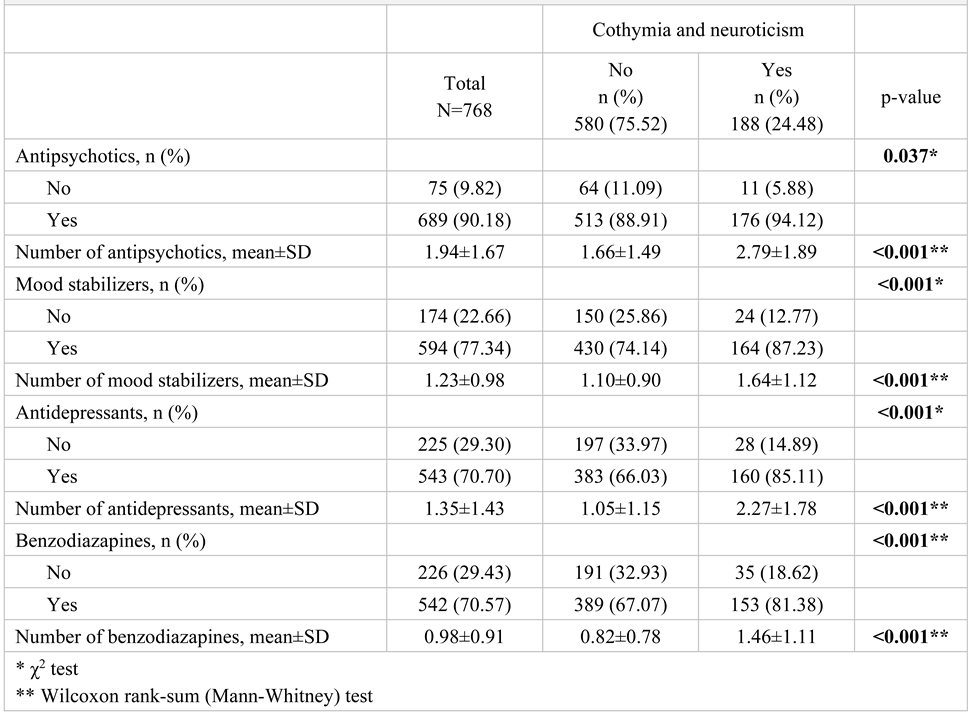

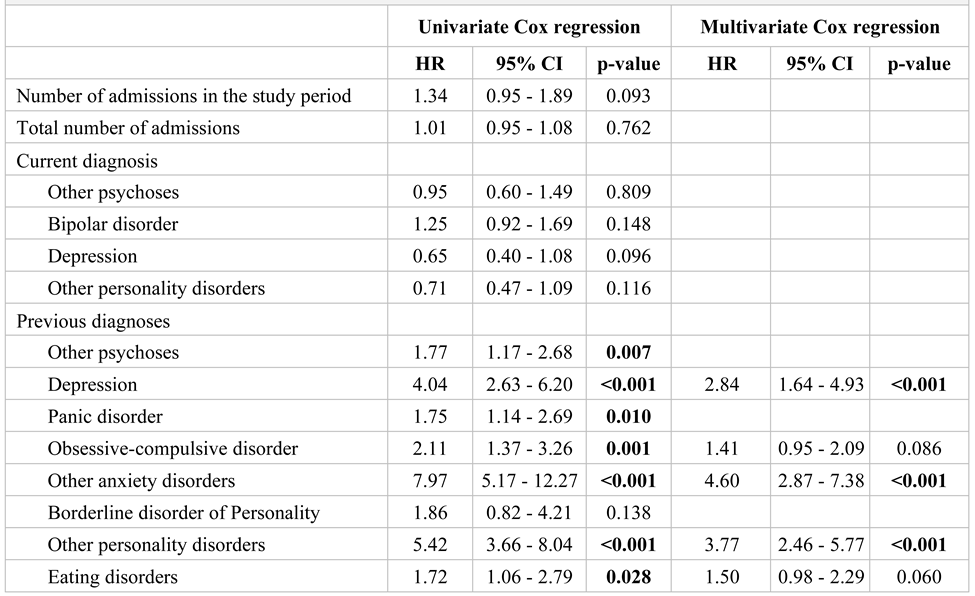

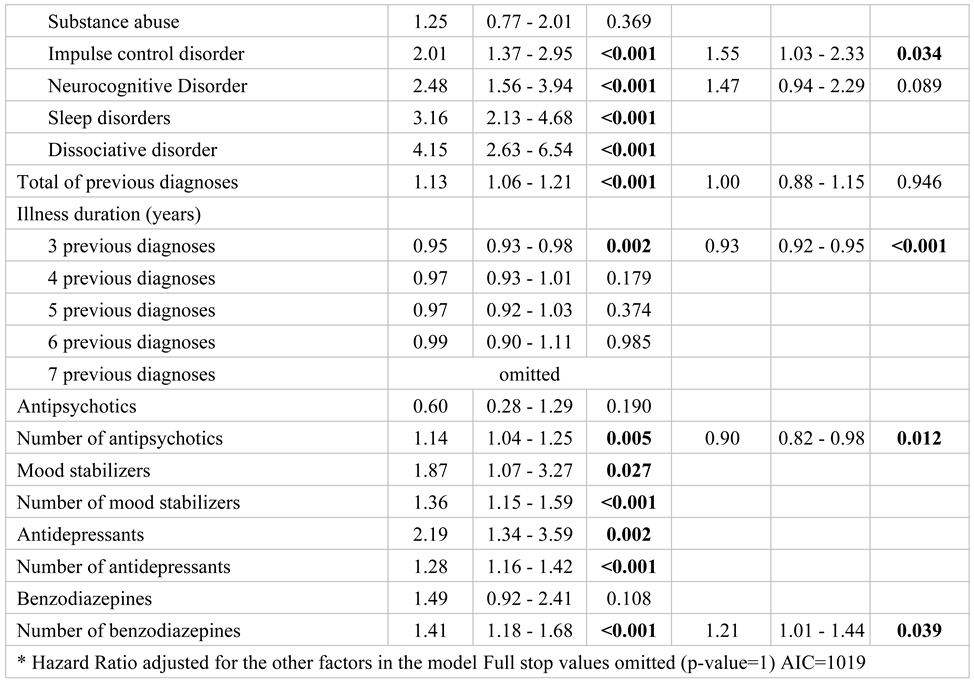

Results

Limitations

Discussions

Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marshall, M. The hidden links between mental disorders. Nature 2020, 581, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, A.; Mattei, A.; Arnone, F.; Barbieri, A.; Basile, V.; Cedro, C.; Celebre, L.; Mento, C.; Rizzo, A.; Silvestri, M.C.; et al. Lifetime Psychiatric Comorbidity and Diagnostic Trajectories in an Italian Psychiatric Sample. Clin Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; Houts, R.M.; Ambler, A.; Danese, A.; Elliott, M.L.; Hariri, A.; Harrington, H.; Hogan, S.; Poulton, R.; Ramrakha, S.; et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Disorders and Comorbidities Across 4 Decades Among Participants in the Dunedin Birth Cohort Study. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel, M.M.; Pan, P.M.; Hoffmann, M.S.; Gadelha, A.; Rosário, M.C.D.; Mari, J.J.; Manfro, G.G.; Miguel, E.C.; Paus, T.; Bressan, R.A.; et al. A general psychopathology factor (P factor) in children: Structural model analysis and external validation through familial risk and child global executive function. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, A.L.; Eisner, M.; Ribeaud, D. The Development of the General Factor of Psychopathology ‘p Factor’ Through Childhood and Adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E. All for One and One for All: Mental Disorders in One Dimension. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrer, P.; Seivewright, H.; Simmonds, S.; Johnson, T. Prospective studies of cothymia (mixed anxiety-depression): how do they inform clinical practice? Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2001, 251 (Suppl. 2), II53–II56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demyttenaere, K.; Heirman, E. The blurred line between anxiety and depression: hesitations on comorbidity, thresholds and hierarchy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrer, P.; Seivewright, H.; Johnson, T. The Core Elements of Neurosis: Mixed Anxiety-Depression (Cothymia) and Personality Disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 2003, 17, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohi, K.; Otowa, T.; Shimada, M.; Sasaki, T.; Tanii, H. Shared genetic etiology between anxiety disorders and psychiatric and related intermediate phenotypes. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, D.H.; Ellard, K.K.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Bullis, J.R.; Carl, J.R. The Origins of Neuroticism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 9, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maj, M. ‘Psychiatric comorbidity’: an artefact of current diagnostic systems? Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 186, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, J.F.; Fagin-Jones, S. Diagnosing and Treating Anxiety Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorders. Psychiatr. Ann. 2004, 34, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Giacomo, E.; Colmegna, F.; Biagi, E.; Zappa, L.; Caslini, M.; Dakanalis, A.; Clerici, M. Anxiety and Depression: A Key to Understanding the Complete Expression of Personality Disorders. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2020, 209, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoorthy, M.S.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: An overview of trends in research. World J. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altay, M.A.; Bozatlı, L.; Şipka, B.D.; Görker, I. Current Pattern of Psychiatric Comorbidity and Psychotropic Drug Prescription in Child and Adolescent Patients. Medicina 2019, 55, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asp, M.; Lindqvist, D.; Fernström, J.; Ambrus, L.; Tuninger, E.; Reis, M.; Westrin, Å. Recognition of personality disorder and anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients treated for depression in secondary psychiatric care. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0227364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upthegrove, R.; Marwaha, S.; Birchwood, M. Depression and Schizophrenia: Cause, Consequence or Trans-diagnostic Issue? Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 43, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O. Network Analysis: An Integrative Approach to the Structure of Psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, A.; Iannuzzo, F.; Muscatello, M.R.A. Comorbidity from a Categorical to a Transdiagnostic-Dimensional Approach: New Perspectives for Researchers and Clinicians. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2023, 20, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

|

|

© 2024 by the authors. 2024 Fiammetta Iannuzzo, Fabiana Fiasca, Antonella Mattei, Carmela Mento, Maria Catena Silvestri, Fabrizio Turiaco, Rocco Antonio Zoccali, Maria Rosaria Anna Muscatello, Antonio Bruno.

Share and Cite

Iannuzzo, F.; Fiasca, F.; Mattei, A.; Mento, C.; Silvestri, M.C.; Turiaco, F.; Zoccali, R.A.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Bruno, A. Syndrome or Symptoms? Assessing Cothymia, Neuroticism and Lifetime Comorbidity in a Sample of Psychiatric Patients. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2024, 11, 106-113. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1460

Iannuzzo F, Fiasca F, Mattei A, Mento C, Silvestri MC, Turiaco F, Zoccali RA, Muscatello MRA, Bruno A. Syndrome or Symptoms? Assessing Cothymia, Neuroticism and Lifetime Comorbidity in a Sample of Psychiatric Patients. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2024; 11(1):106-113. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1460

Chicago/Turabian StyleIannuzzo, Fiammetta, Fabiana Fiasca, Antonella Mattei, Carmela Mento, Maria Catena Silvestri, Fabrizio Turiaco, Rocco Antonio Zoccali, Maria Rosaria Anna Muscatello, and Antonio Bruno. 2024. "Syndrome or Symptoms? Assessing Cothymia, Neuroticism and Lifetime Comorbidity in a Sample of Psychiatric Patients" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 11, no. 1: 106-113. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1460

APA StyleIannuzzo, F., Fiasca, F., Mattei, A., Mento, C., Silvestri, M. C., Turiaco, F., Zoccali, R. A., Muscatello, M. R. A., & Bruno, A. (2024). Syndrome or Symptoms? Assessing Cothymia, Neuroticism and Lifetime Comorbidity in a Sample of Psychiatric Patients. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 11(1), 106-113. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1460