Correlation Between Radiological Features of Axillary Lymph Nodes with CD4 Count and Plasma Viral Load in Patients with HIV

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Materials and Method

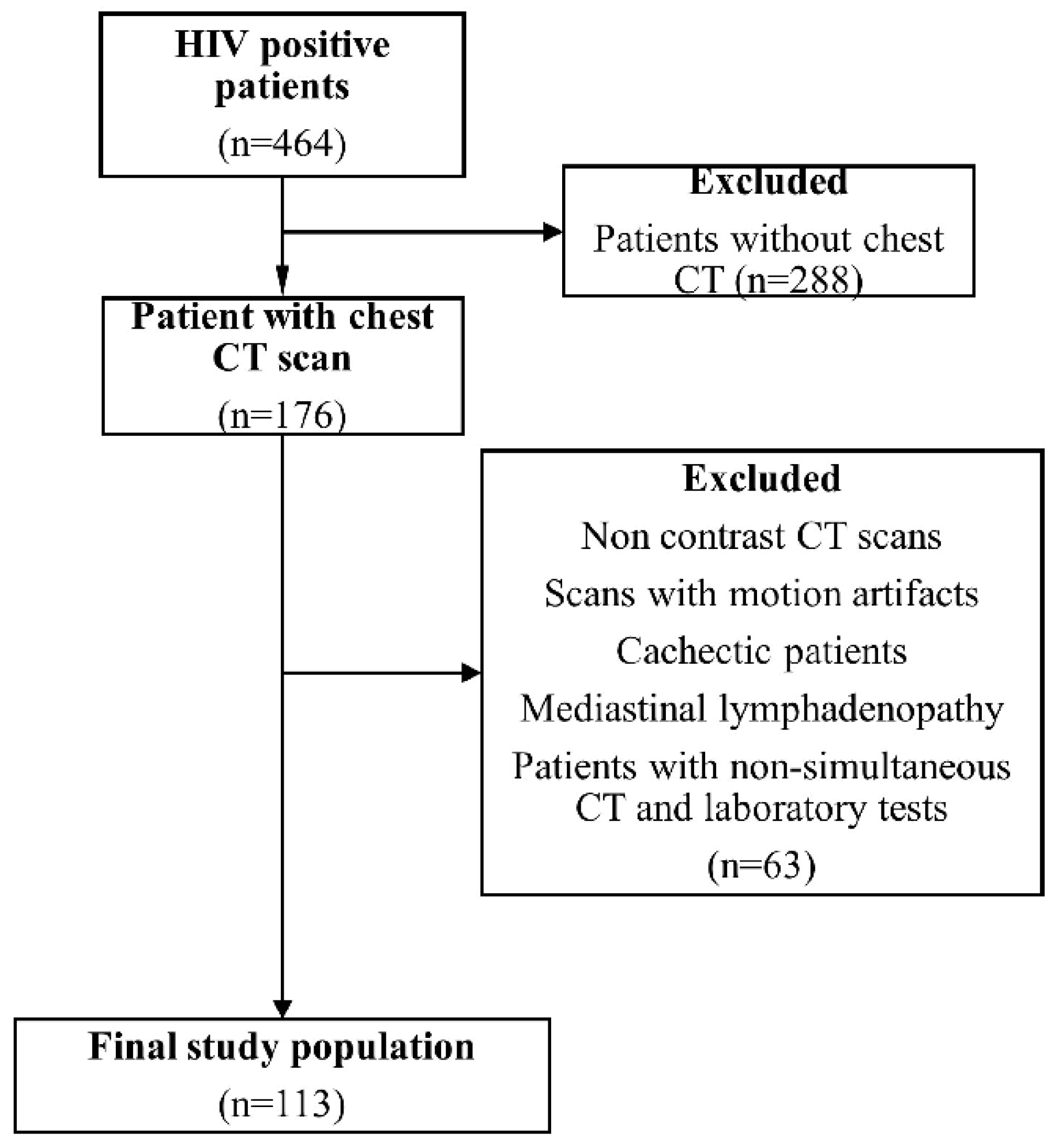

1.2. Subjects

1.3. CT Examination

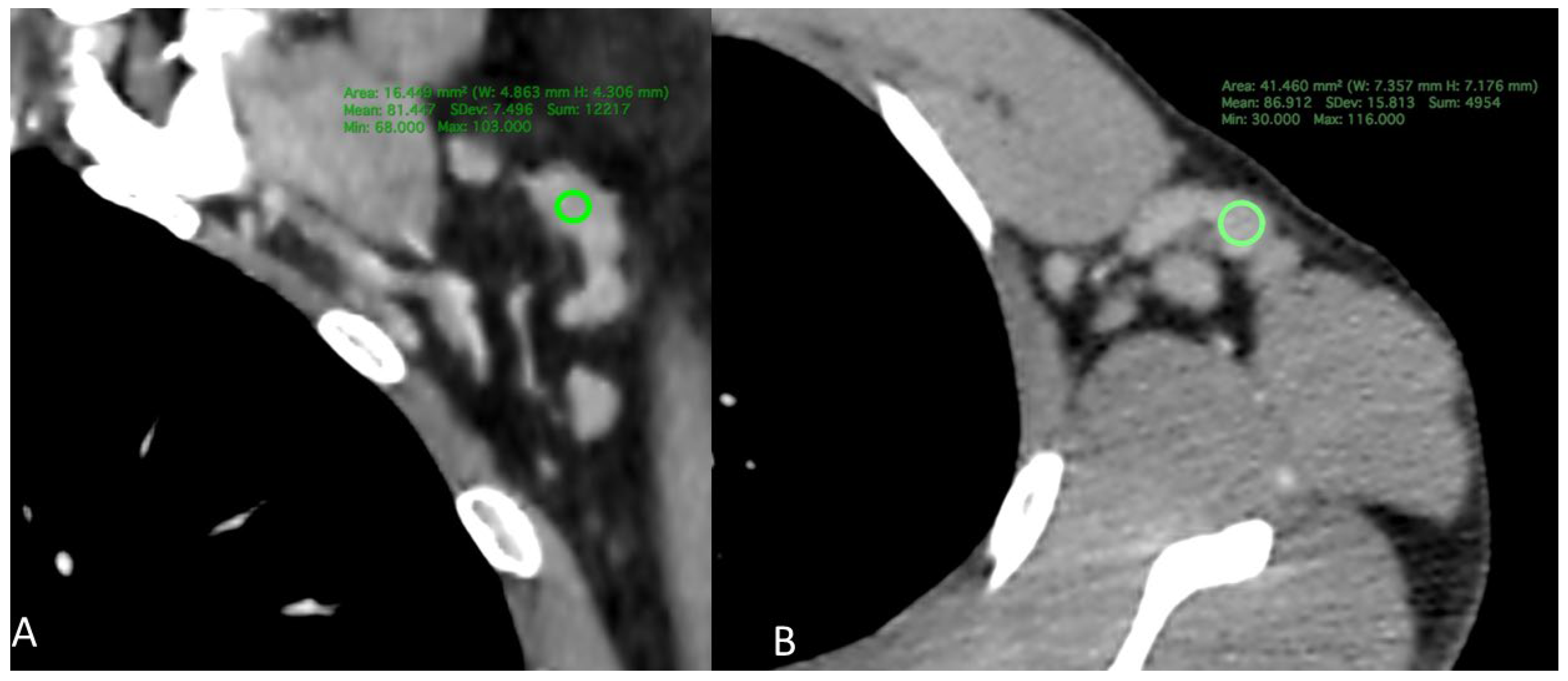

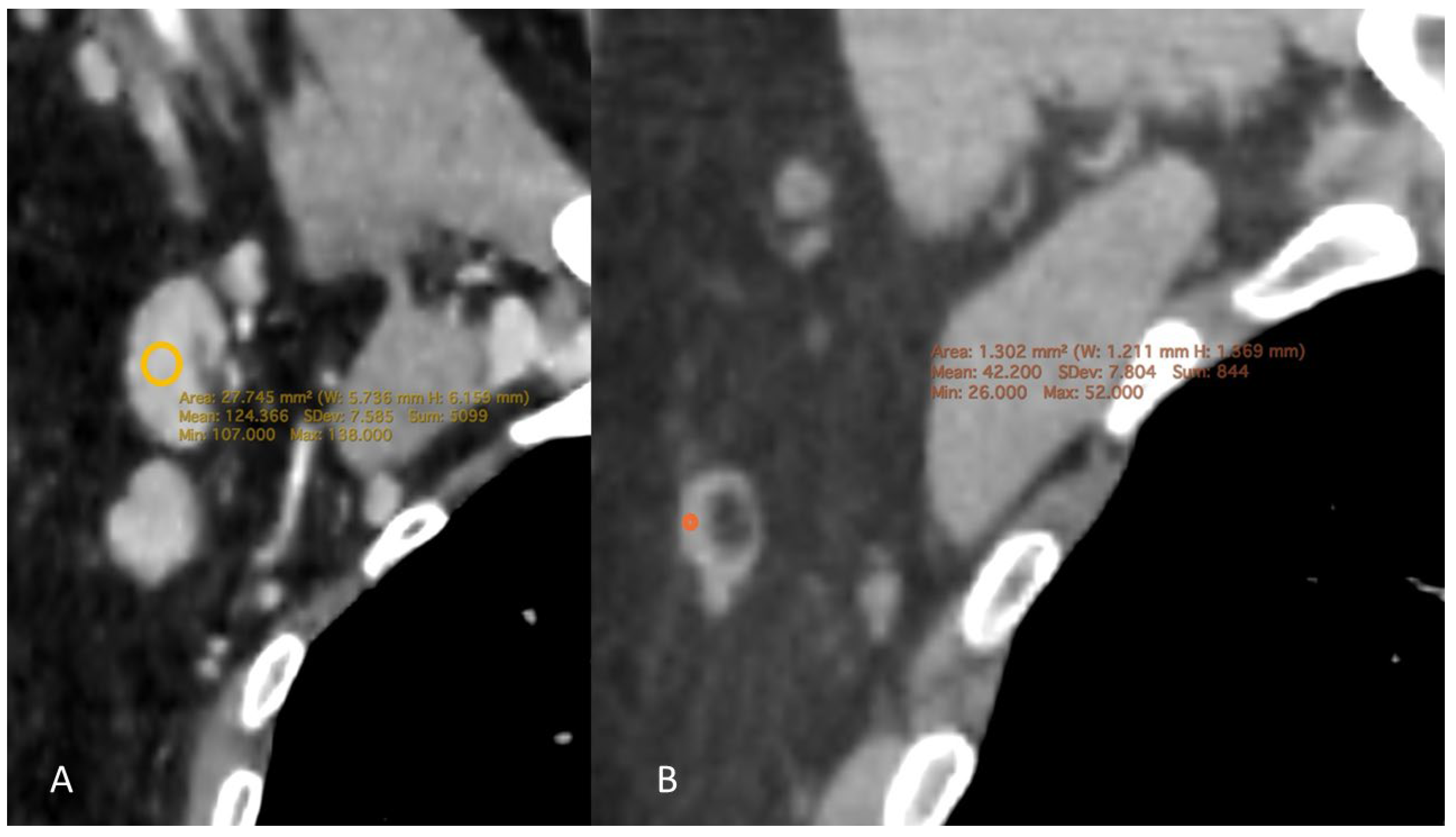

1.4. CT Measurement

1.5. Statistical Analysis

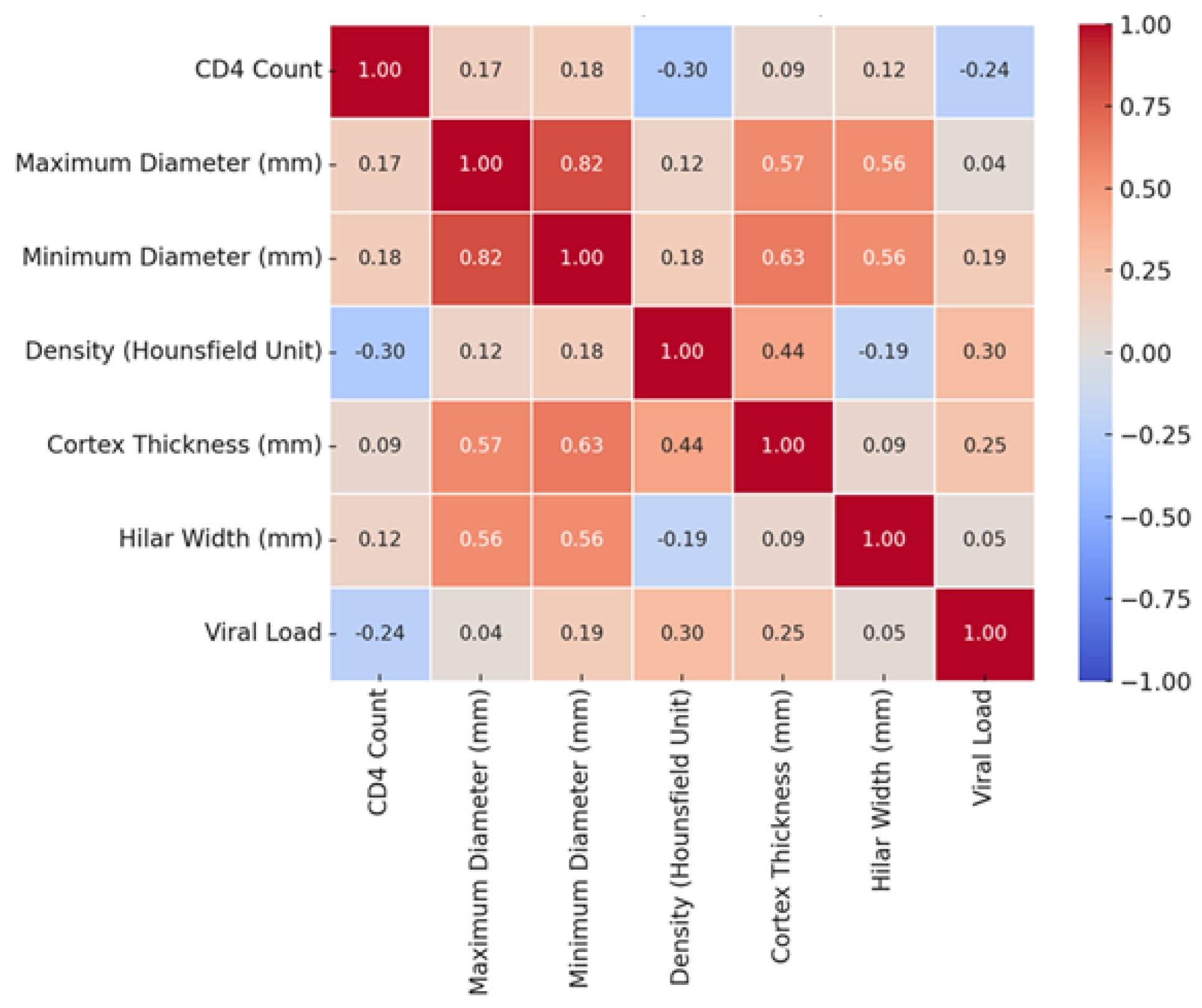

2. Results

2.1. Demographic Findings

2.2. Intraobserver Reliability Findings

2.3. Radiological Findings by CD4 Count

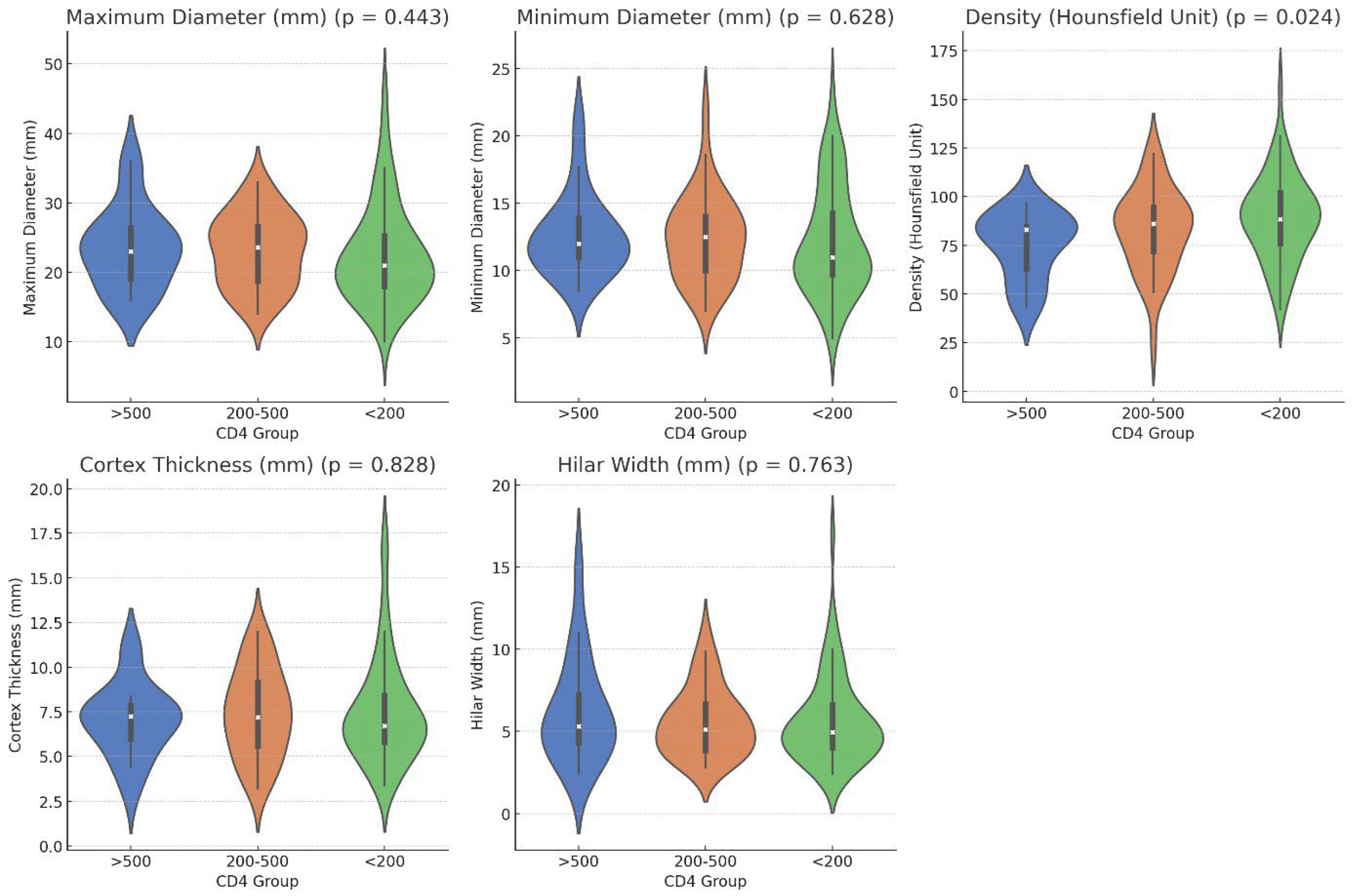

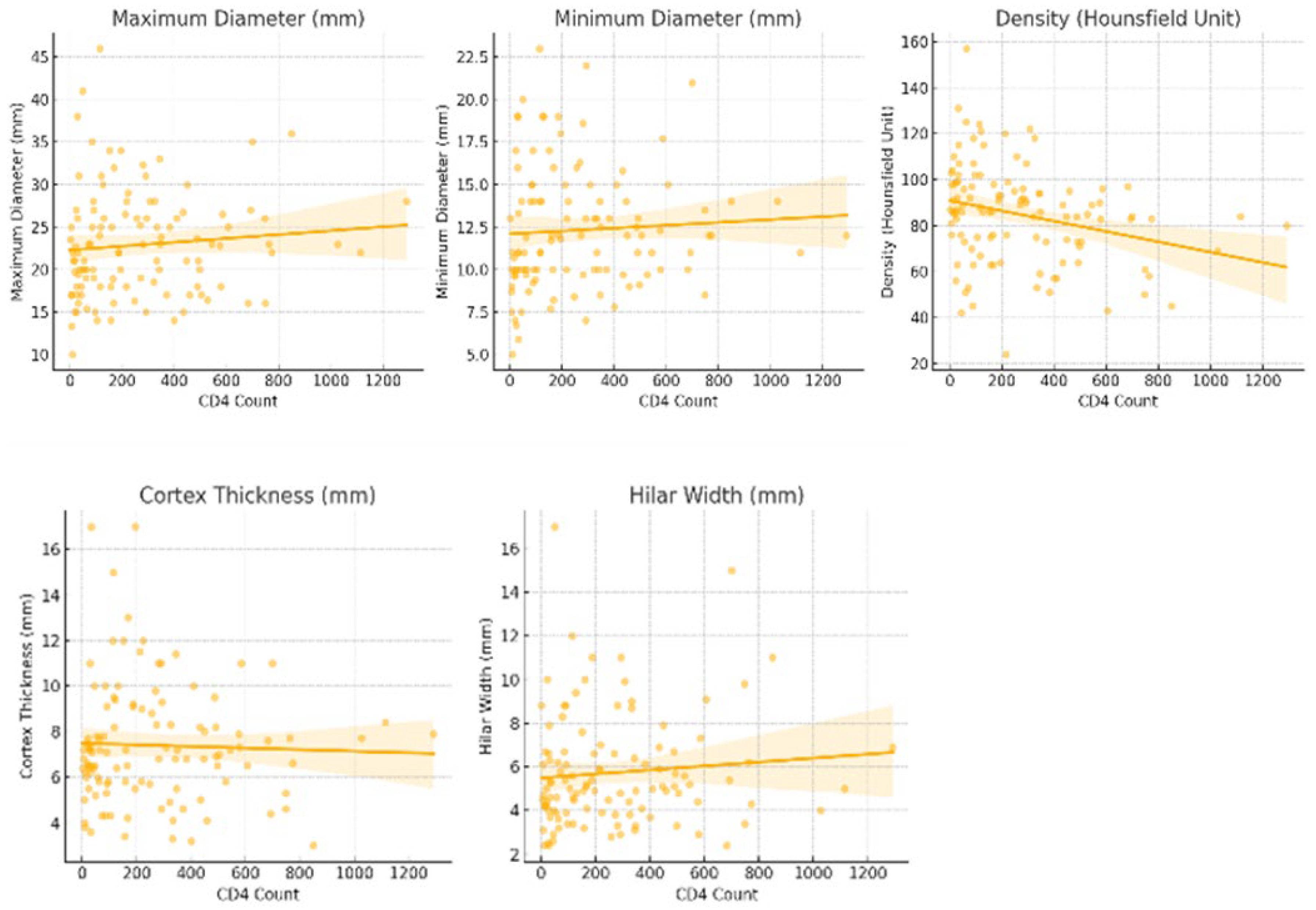

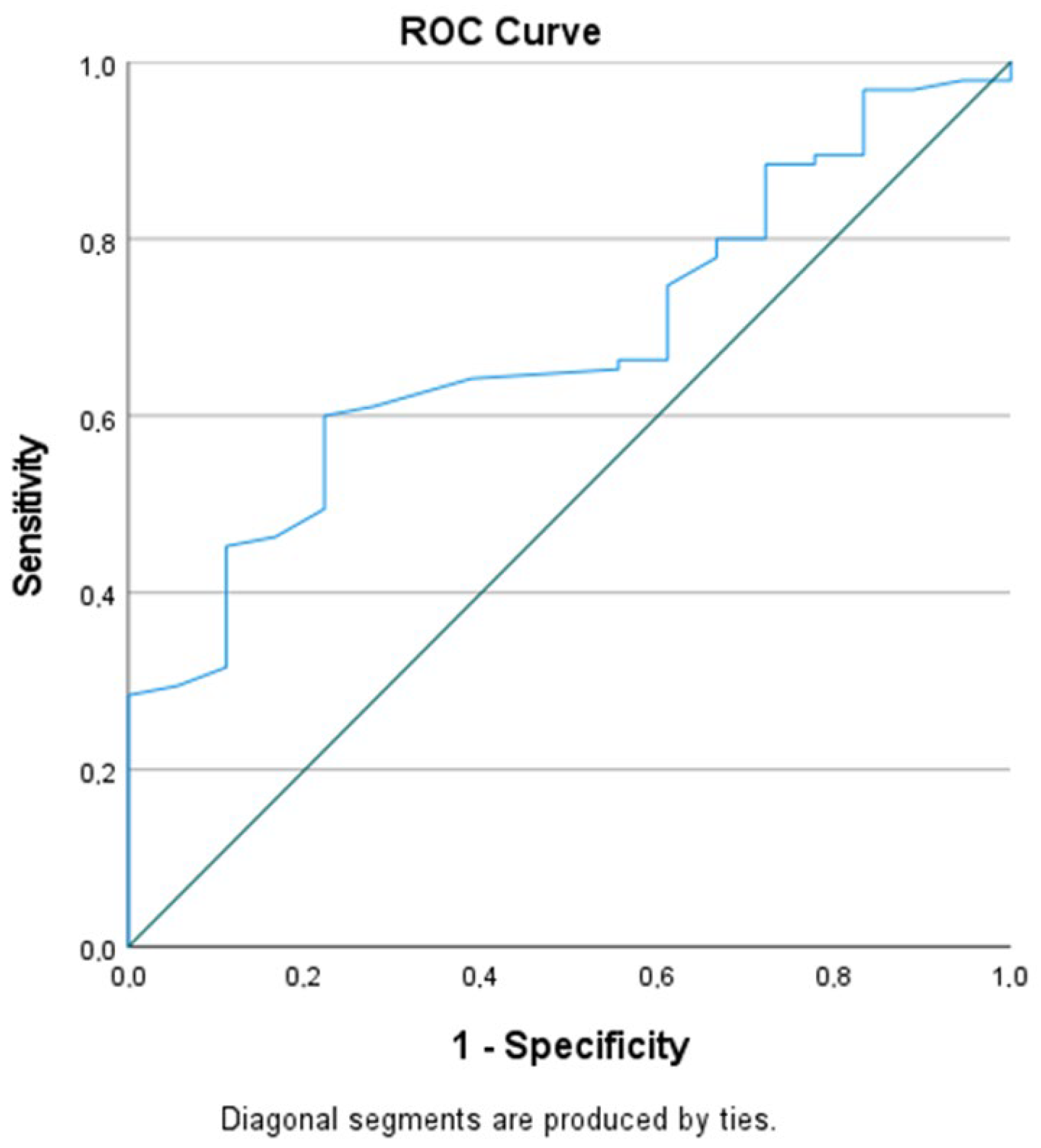

2.4. CD4 Count and Density as a Predictor

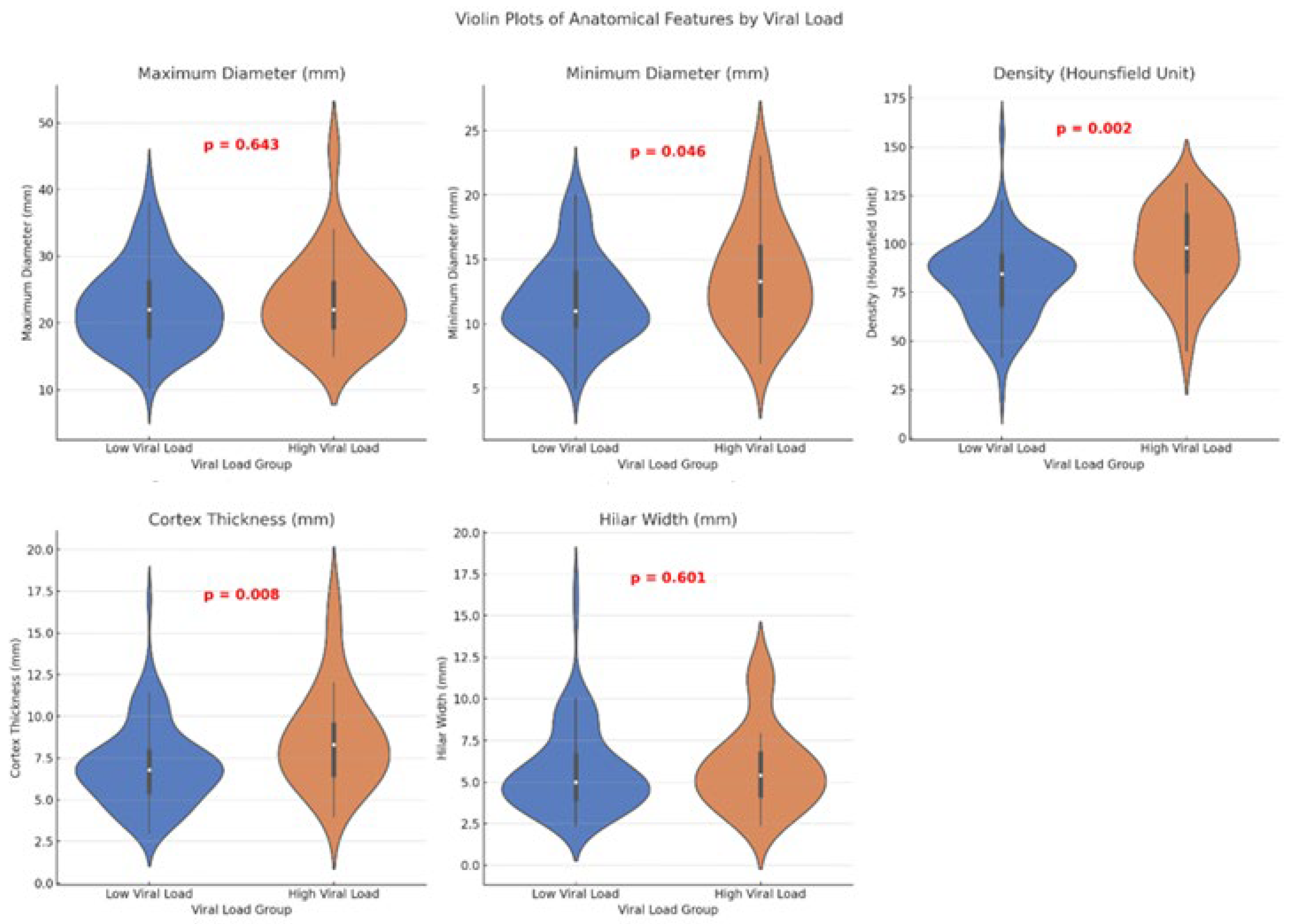

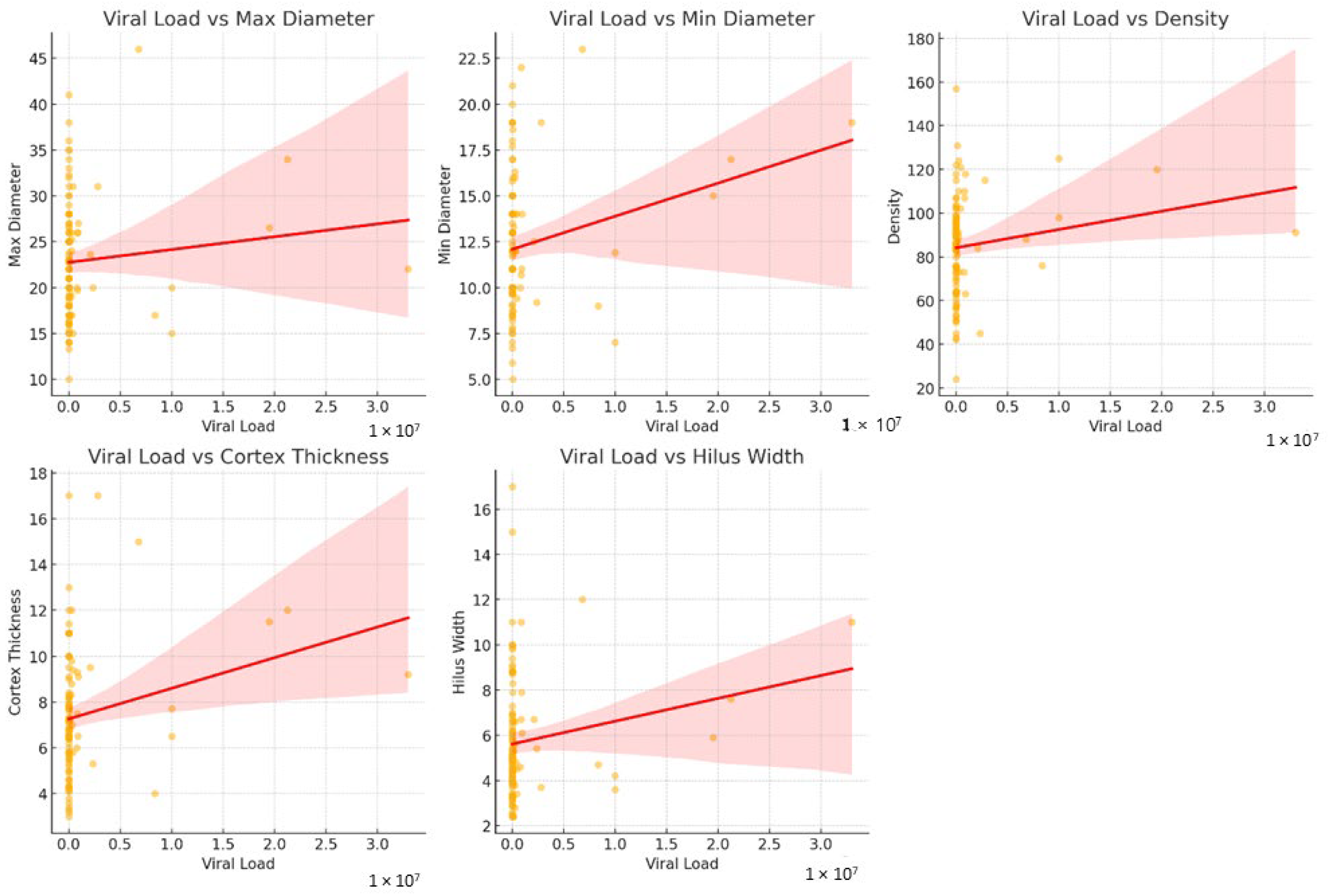

2.5. Radiological Findings by Viral Load

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Del Alcazar, D.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Wendel, B.S.; Del Río-Estrada, P.M.; Lin, J.; Ablanedo-Terrazas, Y.; Malone, M.J.; Hernandez, S.M.; Frank, I.; et al. Mapping the Lineage Relationship between CXCR5+ and CXCR5− CD4+ T Cells in HIV-Infected Human Lymph Nodes. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3047–3060.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, D.; Dey, S.; Nandi, A.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; Roychowdhury, D.; Roy, R. Etiological Study of Lymphadenopathy in HIV-Infected Patients in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Cytol. 2016, 33, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushko, T.; He, L.; McNamee, W.; Babu, A.S.; Simpson, S.A. HIV Lymphadenopathy: Differential Diagnosis and Important Imaging Features. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 216, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, S.; Orfanakis, M.; Brenna, C.; Burgermeister, S.; Del Río-Estrada, P.M.; González-Navarro, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.; Reyes-Terán, G.; Avila-Rios, S.; Luna-Villalobos, Y.A.; et al. Follicular Immune Landscaping Reveals a Distinct Profile of FOXP3hiCD4hi T Cells in Treated Compared to Untreated HIV. Vaccines 2024, 12, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimeková, K.; Nováková, E.; Rosoľanka, R.; Masná, J.; Antolová, D. Clinical Course of Opportunistic Infections—Toxoplasmosis and Cytomegalovirus Infection in HIV-Infected Patients in Slovakia. Pathogens 2019, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, M.H.; Bunachita, S.; Baccouche, B.M.; Hundal, H.; Lavado, L.K.; Agarwal, A.; Malik, P.; Patel, U.K. Forty Years since the Epidemic: Modern Paradigms in HIV Diagnosis and Treatment. Cureus 2021, 13, e14999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, H.; Garg, N.; Qureshi, M.; Chapman, M.; Li, B.; Meibom, S.; Truong, M.T.; Takumi, K.; Sakai, O. CT Texture Analysis of Cervical Lymph Nodes on Contrast-Enhanced FDG PET/CT Images to Differentiate Nodal Metastases from Reactive Lymphadenopathy in HIV-Positive Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2019, 40, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, L.; Mackenzie, S.; Bomanji, J.; Shortman, R.; Noursadeghi, M.; Edwards, S.; Miller, R. FDG PET/CT Imaging in HIV-Infected Patients with Lymphadenopathy, with or without Fever and/or Splenomegaly. Clin. Med. 2018, 18, 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Poultsidi, A.; Dimopoulos, Y.; He, T.-F.; Chavakis, T.; Saloustros, E.; Lee, P.P.; Petrovas, C. Lymph Node Cellular Dynamics in Cancer and HIV: What Can We Learn for the Follicular CD4 (Tfh) Cells? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Su, X.; Li, L. Clinical Features and FDG PET/CT for Distinguishing Malignant Lymphoma from Inflammatory Lymphadenopathy in HIV-Infected Patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi, G.J.; Hekmatnia, A.; Hekmatnia, F.; Zarei, A.P.; Shafieyoon, S.; Azizollahi, S.; Hashemi, M.G.; Riahi, F. Recent Advancements in FDG PET/CT for the Diagnosis, Staging, and Treatment Management of HIV-Related Lymphoma. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 14, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, M.N.; Green, C.; Akin, E.A. Spectrum of FDG PET/CT Findings in Benign Lymph Node Pathology. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2021, 23, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakeres, D.W.; Zawodniak, L.J.; Bornstein, R.; McGhee, R.; Whitacre, C.C. MR Imaging of Head and Neck Adenopathy in Asymptomatic HIV-Seropositive Men. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1993, 14, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franquet, T. Respiratory Infection in the AIDS and Immunocompromised Patient. Eur. Radiol. Suppl. 2004, 14, E21–E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, J.C.; Durand, D.; Tsai, H.-L.; Durand, C.M.; Leal, J.P.; Wang, H.; Moore, R.; Wahl, R.L. Differentiation of HIV-Associated Lymphoma from HIV-Associated Reactive Adenopathy Using Quantitative FDG PET and Symmetry. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 41, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, E.; Lapuerta, P.; Martin, S. Fine Needle Aspiration in HIV-Positive Patients: Results from a Series of 655 Aspirates. Cytopathology 1998, 9, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.-X.; Deng, Y.-Y.; Liu, S.-T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.-X.; Wang, Y.-X.J.; Zhu, W.K.; Le, X.H.; Yu, W.Y.; Zhou, B.P. Correlation between Imaging Features of Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonitis, CD4+ T Lymphocyte Count, and Plasma HIV Viral Load: A Study in 50 Consecutive AIDS Patients. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2012, 2, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, J.D. Pathobiology of HIV/SIV-Associated Changes in Secondary Lymphoid Tissues. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 254, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponetti, G.; Pantanowitz, L. HIV-Associated Lymphadenopathy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008, 87, 374–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, A.; Alós, L.; León, A.; Mozos, A.; Caballero, M.; Martinez, A.; Plana, M.; Gallart, T.; Gil, C.; Leal, M.; et al. Factors Associated with Collagen Deposition in Lymphoid Tissue in Long-Term Treated HIV-Infected Patients. AIDS 2010, 24, 2029–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Southern, P.J.; Reilly, C.S.; Beilman, G.J.; Chipman, J.G.; Schacker, T.W.; Haase, A.T. Lymphoid Tissue Damage in HIV-1 Infection Depletes Naive T Cells and Limits T Cell Reconstitution after Antiretroviral Therapy. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhry, S.; Abdel Rahman, R.W.; Saied, H.M.; Saif El-Nasr, S.I. Can Computed Tomography Predict Nodal Metastasis in Breast Cancer Patients? Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2022, 53, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessner, J.; Anders, L.; Herbert, S.; Kiesel, M.; Bley, T.; Schlaiss, T.; Sauer, S.; Wöckel, A.; Bartmann, C. Evaluation of Different Imaging Modalities for Axillary Lymph Node Staging in Breast Cancer Patients to Provide a Personalized and Optimized Therapy Algorithm. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 3457–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters * | CD4 < 200 (n = 60) | CD4 > 200; CD4 < 500 (n = 35) | CD4 > 500 (n = 18) | p Value ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Diameter (mm) | 22.55 ± 7.09 21 (7.8) | 23.14 ± 5.20 23.60 (8.2) | 23.48 ± 5.84 23 (8.9) | 0.443 |

| Minimum Diameter (mm) | 12.18 ± 3.98 11 (5.1) | 12.40 ±3.19 2.5 (3.19) | 12.59 ± 3.02 12 (3.3) | 0.628 |

| Density (Hounsfield Unit) | 89.12 ± 21.88 88.5 (27) | 82.89 ± 21.22 86 (24) | 75.17 ± 16.97 83 (26) | 0.024 *** |

| Cortex Thickness (mm) | 7.48 ± 2.94 6.7 (3.1) | 7.43 ± 2.45 7.2 (3.8) | 7.05 ± 2.03 7.25 (2.2) | 0.828 |

| Hilar Width (mm) | 5.66 ± 2.66 4.95 (2.6) | 5.57 ± 2.09 5.1 (2.9) | 6.26 ± 3.20 5.3 (3.5) | 0.763 |

| Parameters | Low Viral Load (<100.000 Copies/mL) (n = 88) | High Viral Load (>100.000 Copies/mL) (n = 25) | p Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Diameter (mm) | 22.68 ± 6.18 22 (8.4) | 23.58 ± 6.88 22 (7.1) | 0.643 |

| Minimum Diameter (mm) | 11.91 ± 3.34 11 (4.3) | 13.73 ± 4.09 13.30 (5.8) | 0.046 |

| Density (Hounsfield Unit) | 81.53 ± 20.23 84.50 (27) | 97.04 ± 21.47 98 (32) | 0.002 |

| Cortex Thickness (mm) | 7.09 ± 2.43 6.8 (2.5) | 8.30 (3.2) | 0.008 |

| Hilar Width (mm) | 5.69 ± 2.61 5 (2.7) | 5.86 ± 2.51 5.4 (2.7) | 0.601 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Taskin, G.; Elmali, M.; Deveci, A.; Koc, I.C. Correlation Between Radiological Features of Axillary Lymph Nodes with CD4 Count and Plasma Viral Load in Patients with HIV. Tomography 2026, 12, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010003

Taskin G, Elmali M, Deveci A, Koc IC. Correlation Between Radiological Features of Axillary Lymph Nodes with CD4 Count and Plasma Viral Load in Patients with HIV. Tomography. 2026; 12(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaskin, Gulten, Muzaffer Elmali, Aydin Deveci, and Irem Ceren Koc. 2026. "Correlation Between Radiological Features of Axillary Lymph Nodes with CD4 Count and Plasma Viral Load in Patients with HIV" Tomography 12, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010003

APA StyleTaskin, G., Elmali, M., Deveci, A., & Koc, I. C. (2026). Correlation Between Radiological Features of Axillary Lymph Nodes with CD4 Count and Plasma Viral Load in Patients with HIV. Tomography, 12(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010003