Altered Functional Connectivity of Amygdala Subregions with Large-Scale Brain Networks in Schizophrenia: A Resting-State fMRI Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Functional Connectivity Within Amygdala Subregions

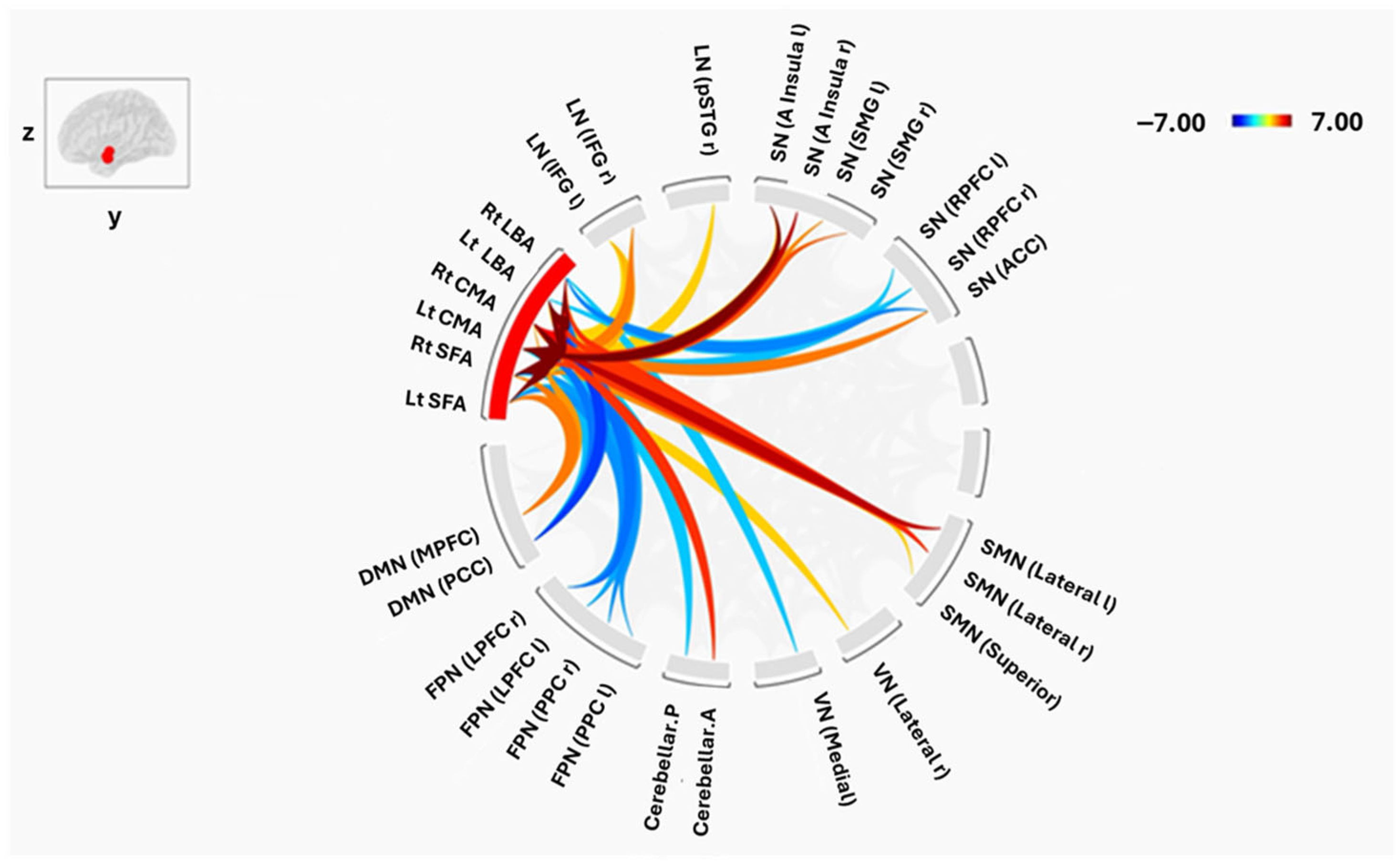

3.2. Connectivity Between Amygdala Subregions and Large-Scale Brain Networks

3.2.1. Laterobasal Amygdala (LBA)

3.2.2. Centromedial Amygdala (CMA)

3.2.3. Superficial Amygdala (SFA)

3.3. Group-Level Differences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Voineskos, A.N.; Hawco, C.; Neufeld, N.H.; Turner, J.A.; Ameis, S.H.; Anticevic, A.; Buchanan, R.W.; Cadenhead, K.; Dazzan, P.; Dickie, E.W.; et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia: Current evidence, methodological advances, limitations and future directions. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabiri, M.; Dehghani Firouzabadi, F.; Yang, K.; Barker, P.B.; Lee, R.R.; Yousem, D.M. Neuroimaging in schizophrenia: A review article. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1042814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steardo, L.; Carbone, E.A.; de Filippis, R.; Pisanu, C.; Segura-Garcia, C.; Squassina, A.; de Fazio, P.; Steardo, L. Application of support vector machine on fmri data as biomarkers in schizophrenia diagnosis: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, R.A.; Reis Marques, T.; Howes, O.D. Schizophrenia—An Overview. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R.; Nasrallah, H.; Akbarian, S.; Carpenter, W.T.; DeLisi, L.E.; Gaebel, W.; Green, M.F.; Gur, R.E.; Heckers, S.; Kane, J.M.; et al. The schizophrenia syndrome, circa 2024: What we know and how that informs its nature. Schizophr. Res. 2024, 264, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ye, H.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, W.; Yang, Y.; Xie, G.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Liang, W.; et al. Amygdala signal abnormality and cognitive impairment in drug-naïve schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohaterewicz, B.; Sobczak, A.M.; Podolak, I.; Wójcik, B.; Mȩtel, D.; Chrobak, A.A.; Fąfrowicz, M.; Siwek, M.; Dudek, D.; Marek, T. Machine Learning-Based Identification of Suicidal Risk in Patients with Schizophrenia Using Multi-Level Resting-State fMRI Features. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 605697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.E.; Glover, G.H. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2015, 25, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswal, B.; Yetkin, F.Z.; Haughton, V.M.; Hyde, J.S. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 1995, 34, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smitha, K.A.; Akhil Raja, K.; Arun, K.M.; Rajesh, P.G.; Thomas, B.; Kapilamoorthy, T.R.; Kesavadas, C. Resting state fMRI: A review on methods in resting state connectivity analysis and resting state networks. Neuroradiol. J. 2017, 30, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Wang, Z.; Tong, E.; Williams, L.M.; Zaharchuk, G.; Zeineh, M.; Goldstein-Piekarski, A.N.; Ball, T.M.; Liao, C.; Wintermark, M. Resting-state functional MRI: Everything that nonexperts have always wanted to know. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuvel, M.P.; Hulshoff Pol, H.E. Exploring the brain network: A review on resting-state fMRI functional connectivity. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010, 20, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosazza, C.; Minati, L. Resting-state brain networks: Literature review and clinical applications. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Smyser, C.D.; Shimony, J.S. Resting-State fMRI: A Review of Methods and Clinical Applications. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013, 34, 1866–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijlers, A.J.C.; Wink, A.M.; Meijer, K.A.; Douw, L.; Geurts, J.J.G.; Schoonheim, M.M. Functional network dynamics on functional MRI: A primer on an emerging frontier in neuroscience. Radiology 2019, 292, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, L.; Xie, Y.; Fang, P. The resting-state cerebro-cerebellar function connectivity and associations with verbal working memory performance. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 417, 113586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machner, B.; Braun, L.; Imholz, J.; Koch, P.J.; Münte, T.F.; Helmchen, C.; Sprenger, A. Resting-State Functional Connectivity in the Dorsal Attention Network Relates to Behavioral Performance in Spatial Attention Tasks and May Show Task-Related Adaptation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 757128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, P.N.; Forkel, S.J.; Corbetta, M.; Thiebaut de Schotten, M. The subcortical and neurochemical organization of the ventral and dorsal attention networks. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Wang, Y.; Chang, X.; Luo, C.; Yao, D. Dysfunction of Large-Scale Brain Networks in Schizophrenia: A Meta-analysis of Resting-State Functional Connectivity. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Hu, N.; Zhang, W.; Tao, B.; Dai, J.; Gong, Y.; Tan, Y.; Cai, D.; Lui, S. Dysconnectivity of multiple brain networks in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, F.; Fan, F.; Wang, Z.; Hong, X.; Tan, Y.; Tan, S.; Hong, L.E. Abnormal amygdala subregional-sensorimotor connectivity correlates with positive symptom in schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 2020, 26, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.X.; Luo, J.X.; Peng, D.; Sun, J.J.; Gao, Y.F.; Hao, L.X.; Tong, B.G.; He, X.M.; Luo, J.Y.; Liang, Z.H.; et al. Brain network functional connectivity changes in long illness duration chronic schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1423008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, I.; Hilal, B. Investigating the association between symptoms and functional activity in brain regions in schizophrenia: A cross-sectional fmri-based neuroimaging study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2024, 344, 111870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallos, I.K.; Mantonakis, L.; Spilioti, E.; Kattoulas, E.; Savvidou, E.; Anyfandi, E.; Karavasilis, E.; Kelekis, N.; Smyrnis, N.; Siettos, C.I. The relation of integrated psychological therapy to resting state functional brain connectivity networks in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 306, 114270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvanfard, F.; Schmid, A.K.; Moghaddam, A.N. Functional Connectivity Alterations of Within and Between Networks in Schizophrenia: A Retrospective Study. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, B.; Huang, H.; Gao, G.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, G. Widespread Intra- and Inter-Network Dysconnectivity among Large-Scale Resting State Networks in Schizophrenia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, P.; Faber, E.S.L.; De Armentia, M.L.; Power, J. The amygdaloid complex: Anatomy and physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 803–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, N.F.; Chong, P.L.H.; Lee, D.R.; Chew, Q.H.; Chen, G.; Sim, K. The Amygdala in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder: A Synthesis of Structural MRI, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, and Resting-State Functional Connectivity Findings. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Flügge, M.C.; Jensen, D.E.A.; Takagi, Y.; Priestley, L.; Verhagen, L.; Smith, S.M.; Rushworth, M.F.S. Relationship between nuclei-specific amygdala connectivity and mental health dimensions in humans. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 1705–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amunts, K.; Kedo, O.; Kindler, M.; Pieperhoff, P.; Mohlberg, H.; Shah, N.J.; Habel, U.; Schneider, F.; Zilles, K. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human amygdala, hippocampal region and entorhinal cortex: Intersubject variability and probability maps. Anat. Embryol. 2005, 210, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, S.B.; Stephan, K.E.; Mohlberg, H.; Grefkes, C.; Fink, G.R.; Amunts, K.; Zilles, K. A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. Neuroimage 2005, 25, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eickhoff, S.B.; Heim, S.; Zilles, K.; Amunts, K. Testing anatomically specified hypotheses in functional imaging using cytoarchitectonic maps. Neuroimage 2006, 32, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eickhoff, S.B.; Paus, T.; Caspers, S.; Grosbras, M.H.; Evans, A.C.; Zilles, K.; Amunts, K. Assignment of functional activations to probabilistic cytoarchitectonic areas revisited. Neuroimage 2007, 36, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdok, D.; Laird, A.R.; Zilles, K.; Fox, P.T.; Eickhoff, S.B. An investigation of the structural, connectional, and functional subspecialization in the human amygdala. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2013, 34, 3247–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerestes, R.; Chase, H.W.; Phillips, M.L.; Ladouceur, C.D.; Eickhoff, S.B. Multimodal evaluation of the amygdala’s functional connectivity. Neuroimage 2017, 148, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, P.B.; Lee, D.S.; Trinh, H.; Tward, D.; Miller, M.I.; Younes, L.; Barta, P.E.; Ratnanather, J.T. Morphometry of the Amygdala in Schizophrenia and Psychotic Bipolar Disorder. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 164, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Cui, D.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J. Study on the sub-regions volume of hippocampus and amygdala in schizophrenia. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2019, 9, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Rando, M.; Penades-Gomiz, C.; Martinez-Marin, P.; García-Martí, G.; Aguilar, E.J.; Escarti, M.J.; Grasa, E.; Corripio, I.; Sanjuan, J.; Nacher, J. Volume alterations of the hippocampus and amygdala in patients with schizophrenia and persistent auditory hallucinations. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2023, 15, S628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, Y.; Womer, F.; Fan, G.; Lu, T.; Driesen, N.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Blumberg, H.P.; et al. Differentiating patterns of amygdala-frontal functional connectivity in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 2014, 40, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldrack, R.A.; Congdon, E.; Triplett, W.; Gorgolewski, K.J.; Karlsgodt, K.H.; Mumford, J.A.; Sabb, F.W.; Freimer, N.B.; London, E.D.; Cannon, T.D.; et al. A phenome-wide examination of neural and cognitive function. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S.; Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2012, 2, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumbley, J.; Worsley, K.; Flandin, G.; Friston, K. Topological FDR for neuroimaging. NeuroImage 2010, 49, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, J.; Cheng, L.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Hao, Z.; Zhan, L.; Shi, Y.; Li, M.; Jia, X.; et al. Altered resting state dynamic functional connectivity of amygdala subregions in patients with autism spectrum disorder: A multi-site fMRI study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 312, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Lau, W.K.W.; Wei, X.; Feng, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Huang, R.; Zhang, R. Anomalous static and dynamic functional connectivity of amygdala subregions in individuals with high trait anxiety. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, P.; Meng, F.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y. Resting-state functional connectivity of the amygdala subregions in unmedicated patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder before and after cognitive behavioural therapy. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2021, 46, E628–E638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, E.M.; Bryant, R.A.; Williamson, T.; Korgaonkar, M.S. Functional connectivity of amygdala subnuclei in PTSD: A narrative review. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3581–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Liu, R.; Wang, C.; Fan, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, G.; et al. Abnormal resting-state functional connectivity in subregions of amygdala in adults and adolescents with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Yu, R. Alterations in Functional Connectivity of Amygdalar Subregions under Acute Social Stress. Neurobiol. Stress 2018, 9, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Raio, C.M.; Pace-Schott, E.F.; Lazar, S.W.; LeDoux, J.E.; Phelps, E.A.; Milad, M.R. Temporally and Anatomically Specific Contributions of the Human Amygdala to Threat and Safety Learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2204066119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.-J.; Bu, H.-B.; Gao, H.; Tong, L.; Wang, L.-Y.; Li, Z.-L.; Yan, B. Altered Amygdala Information Flow during rt-fMRI Neurofeedback Training of Emotion Regulation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Software, Multimedia and Communication Engineering (SMCE 2017), Shanghai, China, 23–24 April 2017; DEStech: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingoia, G.; Wagner, G.; Langbein, K.; Maitra, R.; Smesny, S.; Dietzek, M.; Burmeister, H.P.; Reichenbach, J.R.; Schlösser, R.G.M.; Gaser, C.; et al. Default mode network activity in schizophrenia studied at resting state using probabilistic ICA. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 138, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbasforoushan, H.; Woodward, N.D. Resting-State Networks in Schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 2404–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Song, Y.; Yang, G.; Hao, K.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Lv, L.; Zhang, Y. Abnormal functional connectivity based on nodes of the default mode network in first-episode drug-naive early-onset schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.M.; Palzes, V.A.; Roach, B.J.; Potkin, S.G.; Van Erp, T.G.M.; Turner, J.A.; Mueller, B.A.; Calhoun, V.D.; Voyvodic, J.; Belger, A.; et al. Visual hallucinations are associated with hyperconnectivity between the amygdala and visual cortex in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L.; Adolphs, R. Emotion processing and the amygdala: From a ‘low road’ to ‘many roads’ of evaluating biological significance. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, W.; Fan, X.; Zhang, J.; Geng, D.; Jiang, K.; Zhu, D.; Song, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, D. Resting-state functional connectivity changes within the default mode network and the salience network after antipsychotic treatment in early-phase schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alharthi, R.R.; Banaja, D.; Alahmadi, A.; Alsalah, J.H.; Baeshen, A.; Alghamdi, A.H.; Alelyani, M.; Aldusary, N. Altered Functional Connectivity of Amygdala Subregions with Large-Scale Brain Networks in Schizophrenia: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Tomography 2026, 12, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010002

Alharthi RR, Banaja D, Alahmadi A, Alsalah JH, Baeshen A, Alghamdi AH, Alelyani M, Aldusary N. Altered Functional Connectivity of Amygdala Subregions with Large-Scale Brain Networks in Schizophrenia: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Tomography. 2026; 12(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlharthi, Rasha Rudaid, Duaa Banaja, Adnan Alahmadi, Jaber Hussain Alsalah, Arwa Baeshen, Ali H. Alghamdi, Magbool Alelyani, and Njoud Aldusary. 2026. "Altered Functional Connectivity of Amygdala Subregions with Large-Scale Brain Networks in Schizophrenia: A Resting-State fMRI Study" Tomography 12, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010002

APA StyleAlharthi, R. R., Banaja, D., Alahmadi, A., Alsalah, J. H., Baeshen, A., Alghamdi, A. H., Alelyani, M., & Aldusary, N. (2026). Altered Functional Connectivity of Amygdala Subregions with Large-Scale Brain Networks in Schizophrenia: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Tomography, 12(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography12010002