Clinically Focused Computer-Aided Diagnosis for Breast Cancer Using SE and CBAM with Multi-Head Attention

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

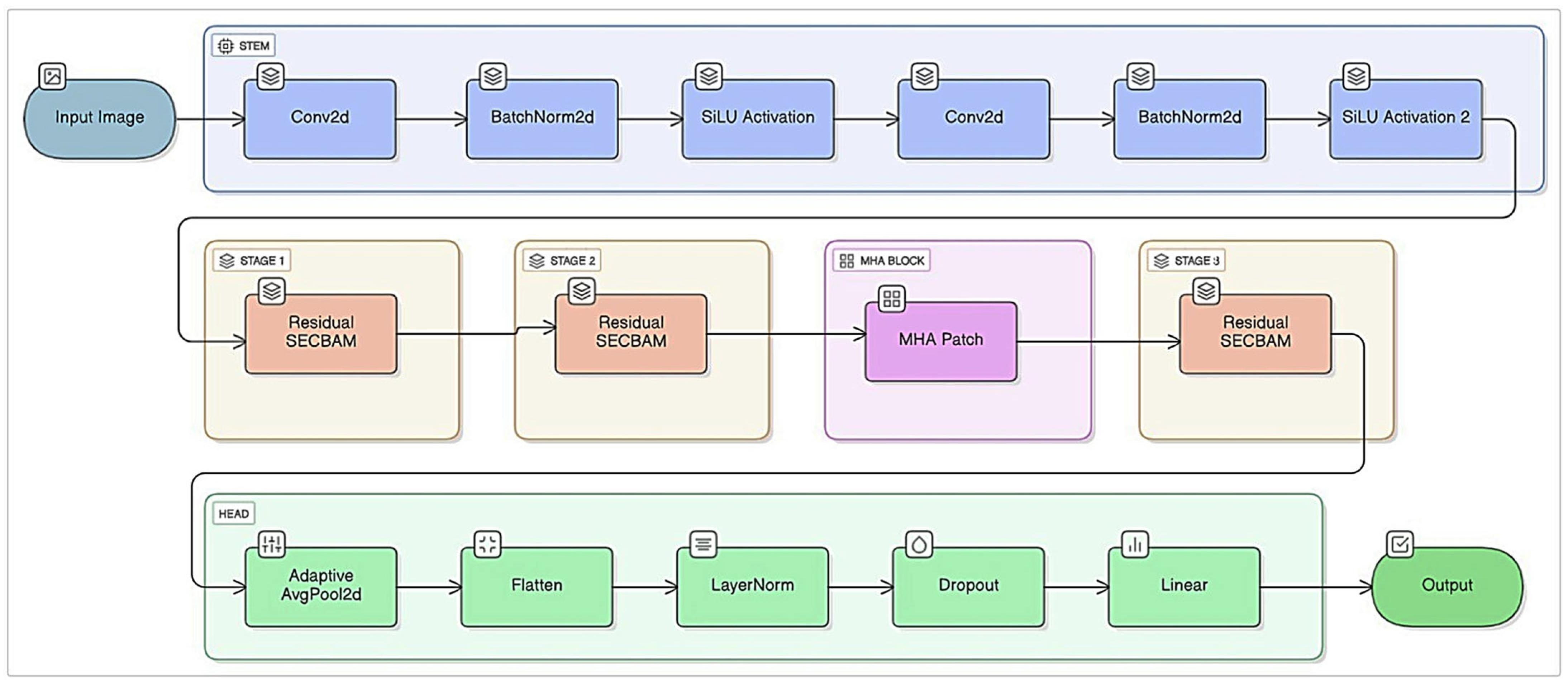

- The proposed model offers a multi-layer hybrid structure by combining CNN-based local feature extraction with Transformer-based global context modeling.

- Thanks to the SE and CBAM-based attention mechanism, which simultaneously calculates channel and spatial importance levels, small but critical morphological differences can be captured in low-contrast and heterogeneous ultrasound images.

- The integration of the Multi-Head Attention layer modeled long-range relationships between the lesion and surrounding tissues, ensuring the inclusion of contextual information in the classification decision.

- The use of Focal Loss in malignant classes with low sample sizes resulted in a significant increase in model sensitivity and F1 score in challenging examples.

- By providing unique methodological contributions to contextual relationship modeling, which classical CNN models lack, and by emphasizing channel and spatial importance, a new framework for breast ultrasound image analysis has been introduced to the literature.

- The developed model achieved 96.03% accuracy on the ultrasound image dataset and 99.55% accuracy on the histopathological image dataset. These values will make significant contributions to the literature in the classification of breast cancer ultrasound and histopathological images.

2. Materials and Methods

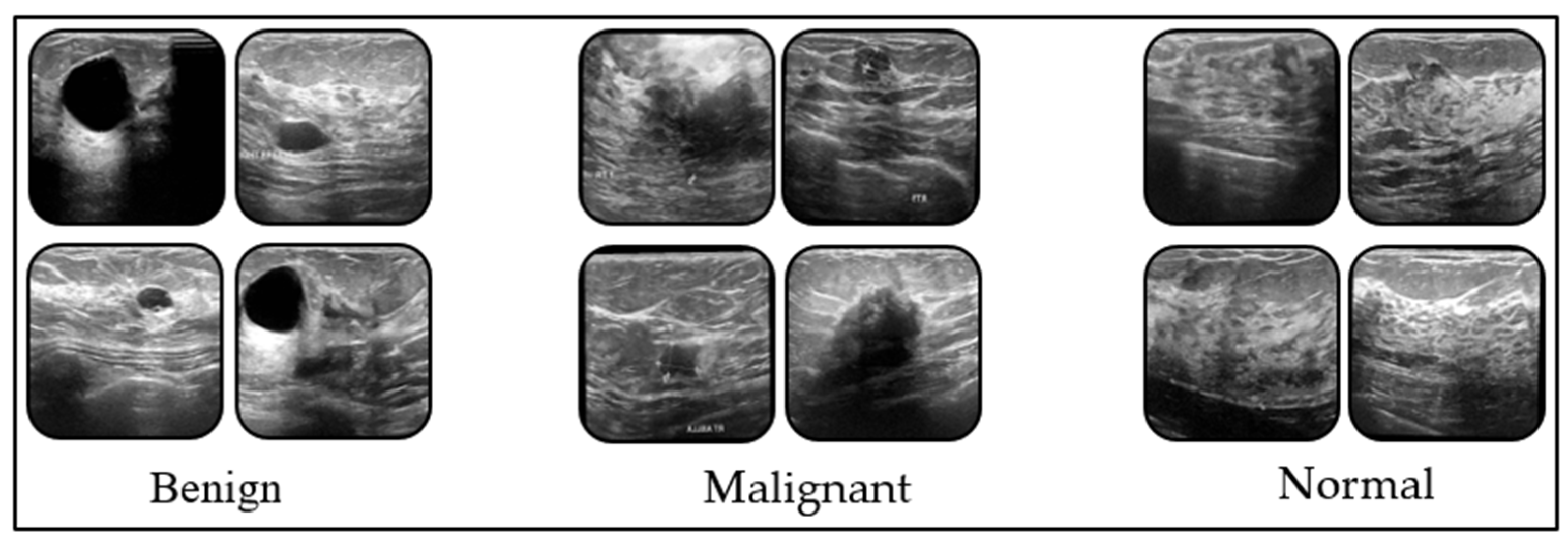

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Proposed Model and Other Models Used in the Study

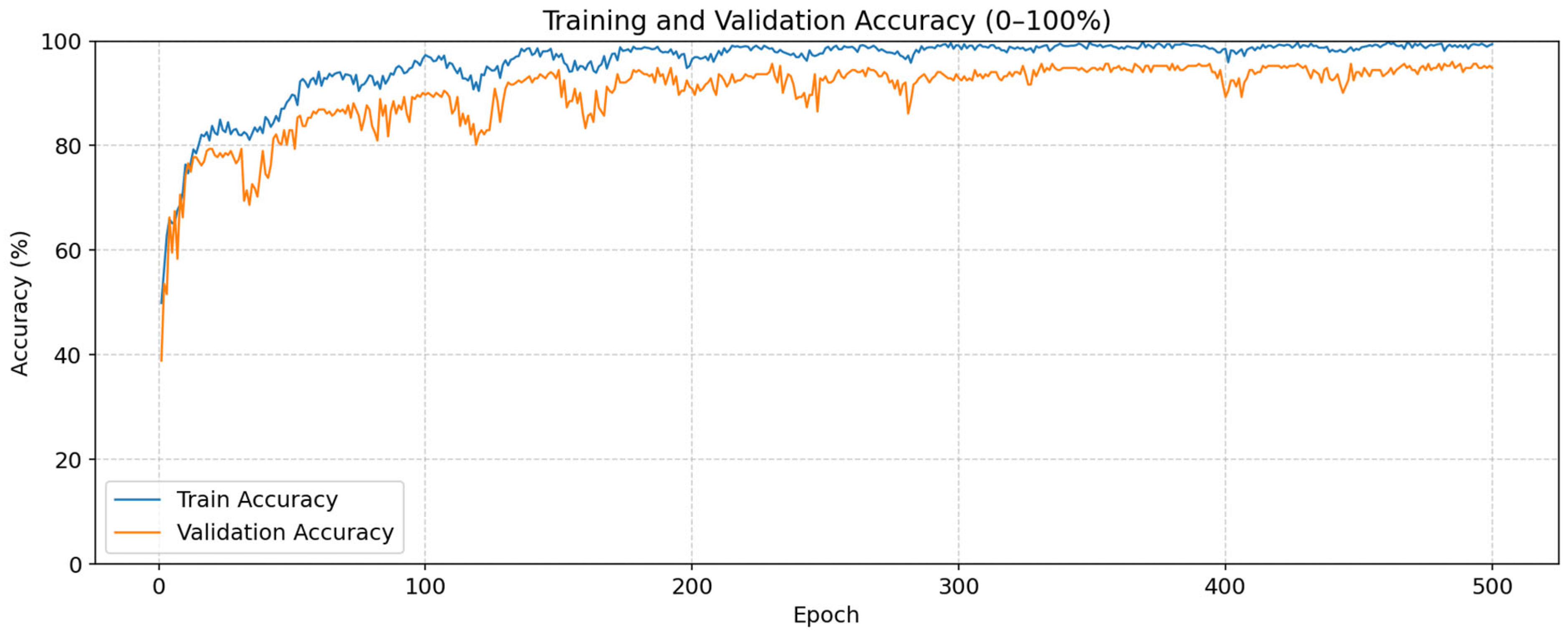

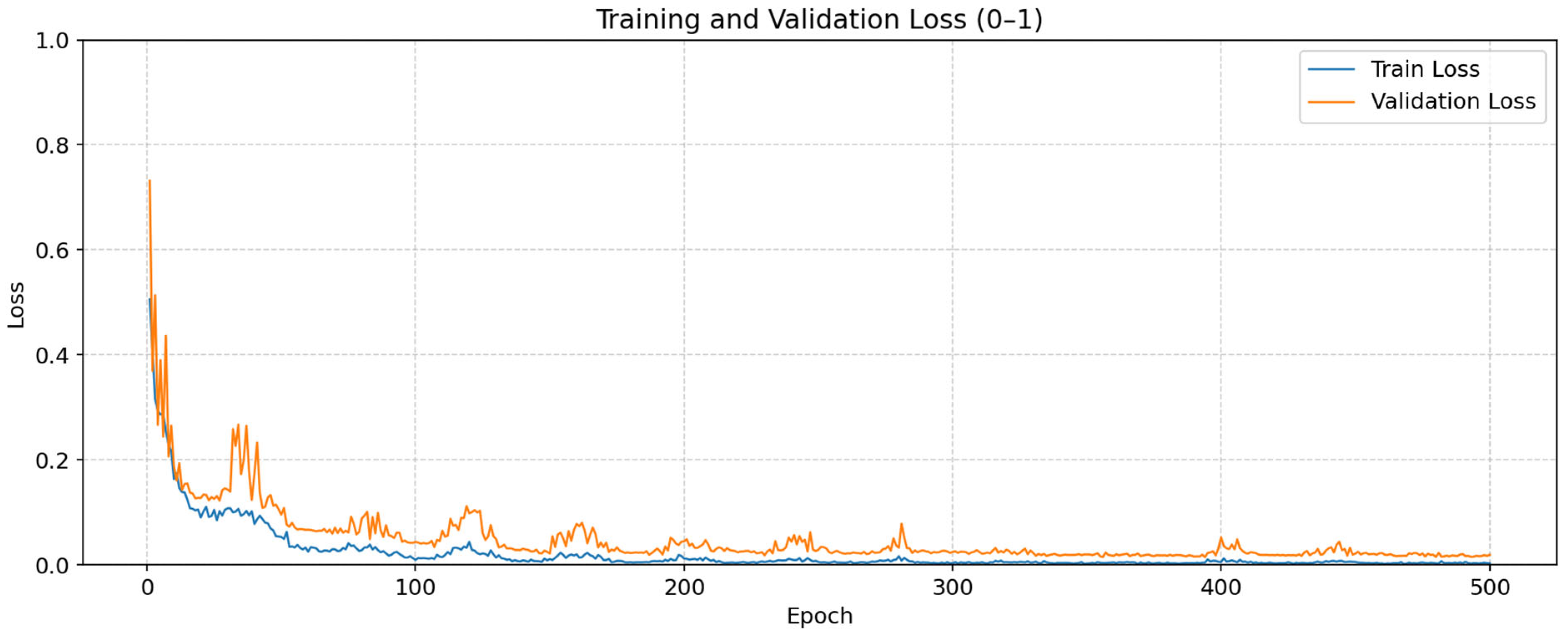

3. Experimental Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shang, C.; Xu, D. Epidemiology of Breast Cancer. Oncologie 2022, 24, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Tang, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhuang, Q. Breast cancer burden among young women from 1990 to 2021: A global, regional, and national perspective. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2025, 34, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Harper, A.; McCormack, V.; Sung, H.; Houssami, N.; Morgan, E.; Mutebi, M.; Garvey, G.; Soerjomataram, I.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. Early diagnosis of breast cancer. Sensors 2017, 17, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, O.; Yip, C.H.; Brooks, A.; Cabanes, A.; Caleffi, M.; Dunstan Yataco, J.A.; Gyawali, B.; McCormack, V.; McLaughlin de Anderson, M.; Mehrotra, R. Breast cancer early detection: A phased approach to implementation. Cancer 2020, 126, 2379–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, R.; Rositch, A.F.; Shakoor, D.; Ambinder, E.; Pool, K.-L.; Pollack, E.; Mollura, D.J.; Mullen, L.A.; Harvey, S.C. Ultrasound for breast cancer detection globally: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Oncol. 2019, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.; Mesurolle, B.; El-Khoury, M.; Kao, E. Breast imaging reporting and data system lexicon for US: Interobserver agreement for assessment of breast masses. Radiology 2009, 252, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, R.; Iacob, E.R.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Ghenciu, D.M.; Cocolea, D.M.; Constantinescu, A.; Ghenciu, L.A.; Manolescu, D.L. Evaluating the role of breast ultrasound in early detection of breast cancer in low-and middle-income countries: A comprehensive narrative review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Velden, B.H.; Kuijf, H.J.; Gilhuijs, K.G.; Viergever, M.A. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in deep learning-based medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 79, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Mehmood, A.; Alabrah, A.; Alkhamees, B.F.; Amin, F.; AlSalman, H.; Choi, G.S. Breast cancer detection and prevention using machine learning. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Deep learning for medical image-based cancer diagnosis. Cancers 2023, 15, 3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, K.; Elahi, H.; Ayub, A.; Frezza, F.; Rizzi, A. Cancer diagnosis using deep learning: A bibliographic review. Cancers 2019, 11, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yala, A.; Lehman, C.; Schuster, T.; Portnoi, T.; Barzilay, R. A deep learning mammography-based model for improved breast cancer risk prediction. Radiology 2019, 292, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhabyani, W.; Gomaa, M.; Khaled, H.; Fahmy, A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data Brief 2020, 28, 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Jahangir, M.Z.B.; Rahman, A.; Akter, M.; Nasim, M.A.A.; Gupta, K.D.; George, R. Breast cancer detection and localizing the mass area using deep learning. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Khan, M.A.U.; Abrar, M.; Tahir, M. Optimizing breast cancer detection with an ensemble deep learning approach. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2024, 2024, 5564649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormpos, C.; Zantalis, F.; Katsoulis, S.; Koulouras, G. Evaluating Deep Learning Architectures for Breast Tumor Classification and Ultrasound Image Detection Using Transfer Learning. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Miao, J.; Yang, X.; Li, R.; Zhou, G.; Huang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xue, W.; Jia, X.; Zhou, J. Auto-weighting for breast cancer classification in multimodal ultrasound. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Lima, Peru, 4–8 October 2020; pp. 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, T.A.; Majidpour, J.; Thinakaran, R.; Batumalay, M.; Dewi, D.A.; Hassan, B.A.; Dadgar, H.; Arabi, H. NSGA-II-DL: Metaheuristic optimal feature selection with deep learning framework for HER2 classification in breast cancer. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 38885–38898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui-Hassani, I.; Pellegrini, T.; Masquelier, T. Dilated convolution with learnable spacings. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.03740. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, J.; Kim, E.; Tzeng, E.; Park, D.H.; Zhai, A.; Kislyuk, D. Toward transformer-based object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.09958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Walid, D. Breast Cancer Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/djaidwalid/breast-cancer-dataset/data (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Berg, W.A.; Bandos, A.I.; Mendelson, E.B.; Lehrer, D.; Jong, R.A.; Pisano, E.D. Ultrasound as the primary screening test for breast cancer: Analysis from ACRIN 6666. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djv367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.S.; Hung, W.K.; Yuen, L.W.; Chan, H.Y.Y.; Chu, C.W.W.; Cheung, P.S.Y. Comparison of Characteristics of Breast Cancer Detected through Different Imaging Modalities in a Large Cohort of Hong Kong Chinese Women: Implication of Imaging Choice on Upcoming Local Screening Program. Breast J. 2022, 2022, 3882936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabaleta, J.; Aguinagalde, B.; Lopez, I.; Fernandez-Monge, A.; Lizarbe, J.A.; Mainer, M.; Ferrer-Bonsoms, J.A.; De Assas, M. Utility of artificial intelligence for decision making in thoracic multidisciplinary tumor boards. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamir, S.B.; Sasson, A.L.; Margolies, L.R.; Mendelson, D.S. New frontiers in breast cancer imaging: The rise of AI. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roadevin, C.; Hill, H. AI interventions in cancer screening: Balancing equity and cost-effectiveness. J. Med. Ethics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankwa-Mullan, I. Health equity and ethical considerations in using artificial intelligence in public health and medicine. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2024, 21, E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Alderman, J.E.; Palmer, J.; Ganapathi, S.; Laws, E.; Mccradden, M.D.; Oakden-Rayner, L.; Pfohl, S.R.; Ghassemi, M.; Mckay, F. The value of standards for health datasets in artificial intelligence-based applications. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2929–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Shen, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Su, G.; Michalopoulou, E.; Peng, W.; Gu, Y.; Guo, W. Artificial intelligence in breast imaging: Current situation and clinical challenges. In Exploration; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; p. 20230007. [Google Scholar]

| Classes | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 98.80 | 93.18 | 95.91 |

| Malignant | 96.43 | 96.43 | 96.43 |

| Normal | 92.94 | 98.75 | 95.76 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConvNeXt-Tiny | 91.67 | 92.00 | 91.77 | 91.71 |

| ViT-B/16 | 92.46 | 92.60 | 92.59 | 92.53 |

| ResNet50 | 92.86 | 93.06 | 92.94 | 92.91 |

| ViT-B/32 | 93.25 | 93.37 | 93.38 | 93.29 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 93.65 | 93.73 | 93.78 | 93.70 |

| DenseNet121 | 94.84 | 94.94 | 94.99 | 94.85 |

| Proposed Model | 96.03 | 96.15 | 96.03 | 96.03 |

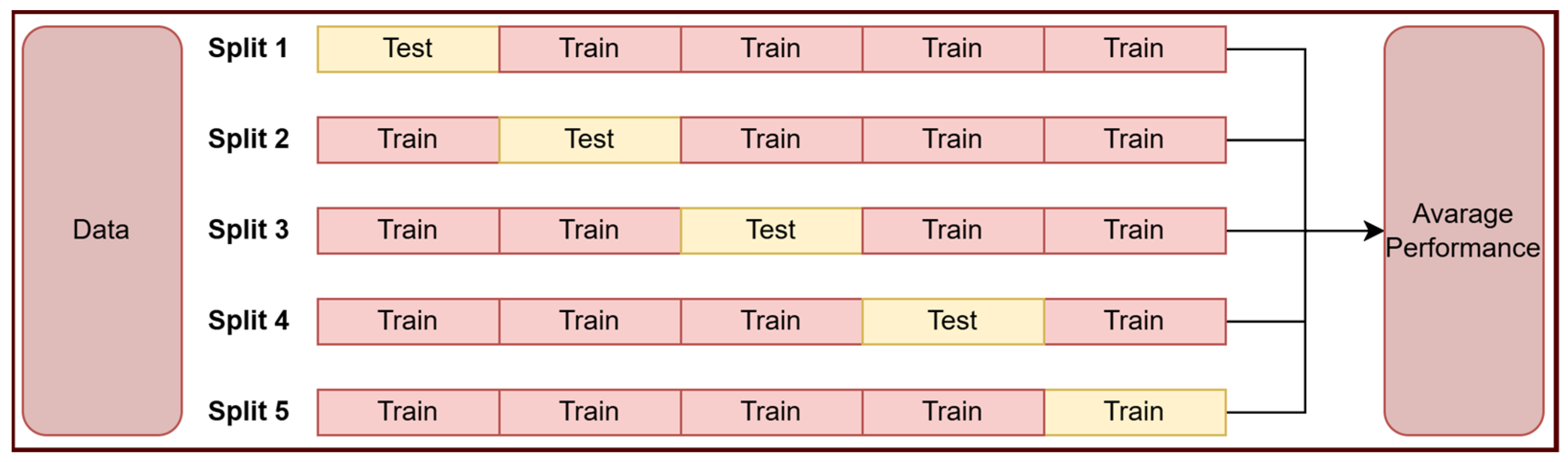

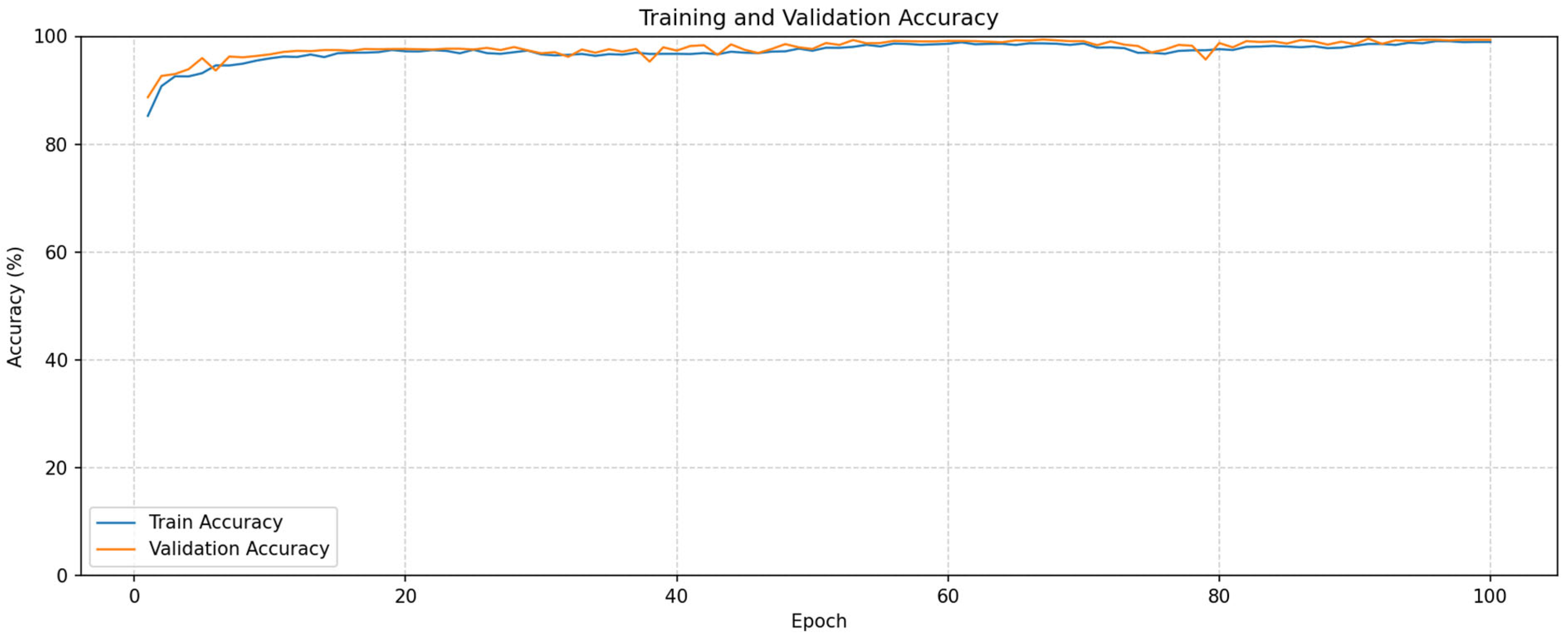

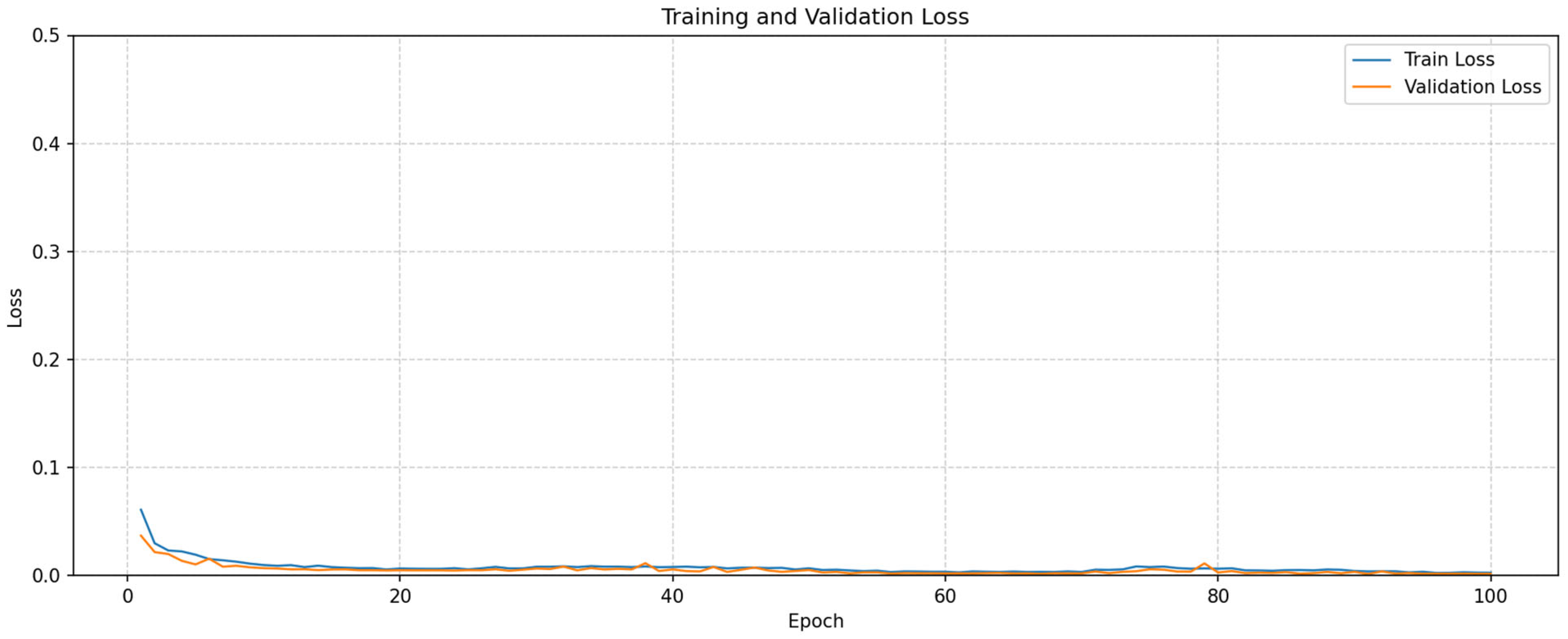

| Fold 1 | Fold 2 | Fold 3 | Fold 4 | Fold 5 | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 99.48 | 99.72 | 99.61 | 99.58 | 99.42 | 99.55 |

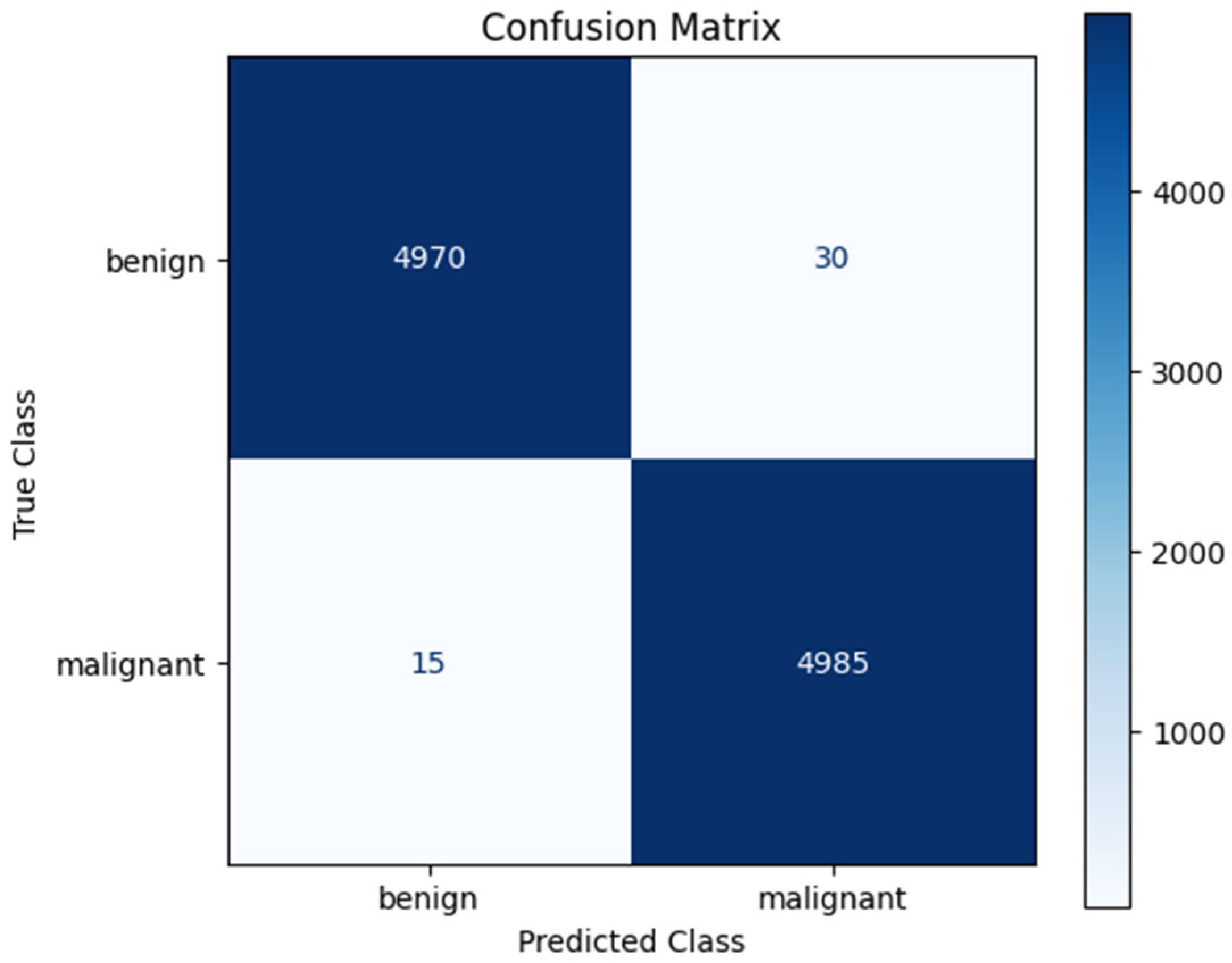

| Classes | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Number of Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 99.70 | 99.40 | 99.55 | 5000 |

| Malignant | 99.40 | 99.70 | 99.55 | 5000 |

| Paper | Year | Methods | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rahman et al. [15] | U-Net and YOLO | Acc: 93% | |

| Shah et al. [16] | 2024 | EfficientNet, AlexNet, ResNet and DenseNet based hybrid model | Acc: 94.6% |

| Kormpos et al. [17] | 2025 | NasNet | Acc: 93.1% |

| Wang et al. [18] | 2020 | Reinforcement learning-based model | Acc: 95.4% |

| Rashid et al. [19] | 2024 | CNN and Metaheuristic based hybrid model | Acc: 94.4% |

| Proposed Model | 2025 | SE-CBAM-MHA based hybrid model | Dataset1: Acc: 96.03% Dataset2: Acc. 99.55% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogut, Z.; Karaduman, M.; Yildirim, M. Clinically Focused Computer-Aided Diagnosis for Breast Cancer Using SE and CBAM with Multi-Head Attention. Tomography 2025, 11, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120138

Ogut Z, Karaduman M, Yildirim M. Clinically Focused Computer-Aided Diagnosis for Breast Cancer Using SE and CBAM with Multi-Head Attention. Tomography. 2025; 11(12):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120138

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgut, Zeki, Mucahit Karaduman, and Muhammed Yildirim. 2025. "Clinically Focused Computer-Aided Diagnosis for Breast Cancer Using SE and CBAM with Multi-Head Attention" Tomography 11, no. 12: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120138

APA StyleOgut, Z., Karaduman, M., & Yildirim, M. (2025). Clinically Focused Computer-Aided Diagnosis for Breast Cancer Using SE and CBAM with Multi-Head Attention. Tomography, 11(12), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography11120138