Analyzing the Impact of Responding to Joint Attention on the User Perception of the Robot in Human-Robot Interaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. User Perception of the Robot in HRI

2.2. Bio-Inspired Mechanisms of Joint Attention

2.3. Joint Attention in Human-Robot Interaction

3. Responsive Joint Attention System

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Social Robot Mini

4.2. Distractive Stimuli

4.3. Odds and Evens Game

5. User Study

- RJAS Active: Participants play the “Odds and Evens” game with the robot while the joint attention system is active. Visual and auditory distractions try to capture the user’s attention while the user is playing the game. If the user gets distracted, the robot will turn towards the user and express verbally that it noticed the distraction.

- RJAS Inactive: A similar setup, but without the robot reacting to the user’s distractions.

5.1. Participants

5.2. Procedure

5.3. Post-Experimental Questionnaire

5.4. Hypotheses

- H0: There will be a difference in the participants’ perception of the robot depending on whether the RJAS is active or not.

- H1: Participants in the active RJAS condition will rate the robot as having higher competence than those interacting with a robot without RJAS. The idea motivating this hypothesis is that when the robot appears to understand and synchronize its actions with the participant’s FoA, it might improve the interaction’s fluency and give the impression of greater problem-solving and task-oriented abilities [37].

- H2: Participants interacting with a robot with an activated RJAS will report higher warmth from the interaction with the robot than those interacting with a robot without RJAS. We expect that using an RJAS might increase the robot’s perceived warmth by encouraging more natural, human-like social interactions [39].

- H3: Participants interacting with a robot with an activated RJAS will report lower levels of discomfort than those interacting with a robot without RJAS. We hypothesise that the active RJAS could avoid awkward interactions by aligning the robot’s behaviour with human social norms, therefore lowering perceived discomfort [47].

6. Results

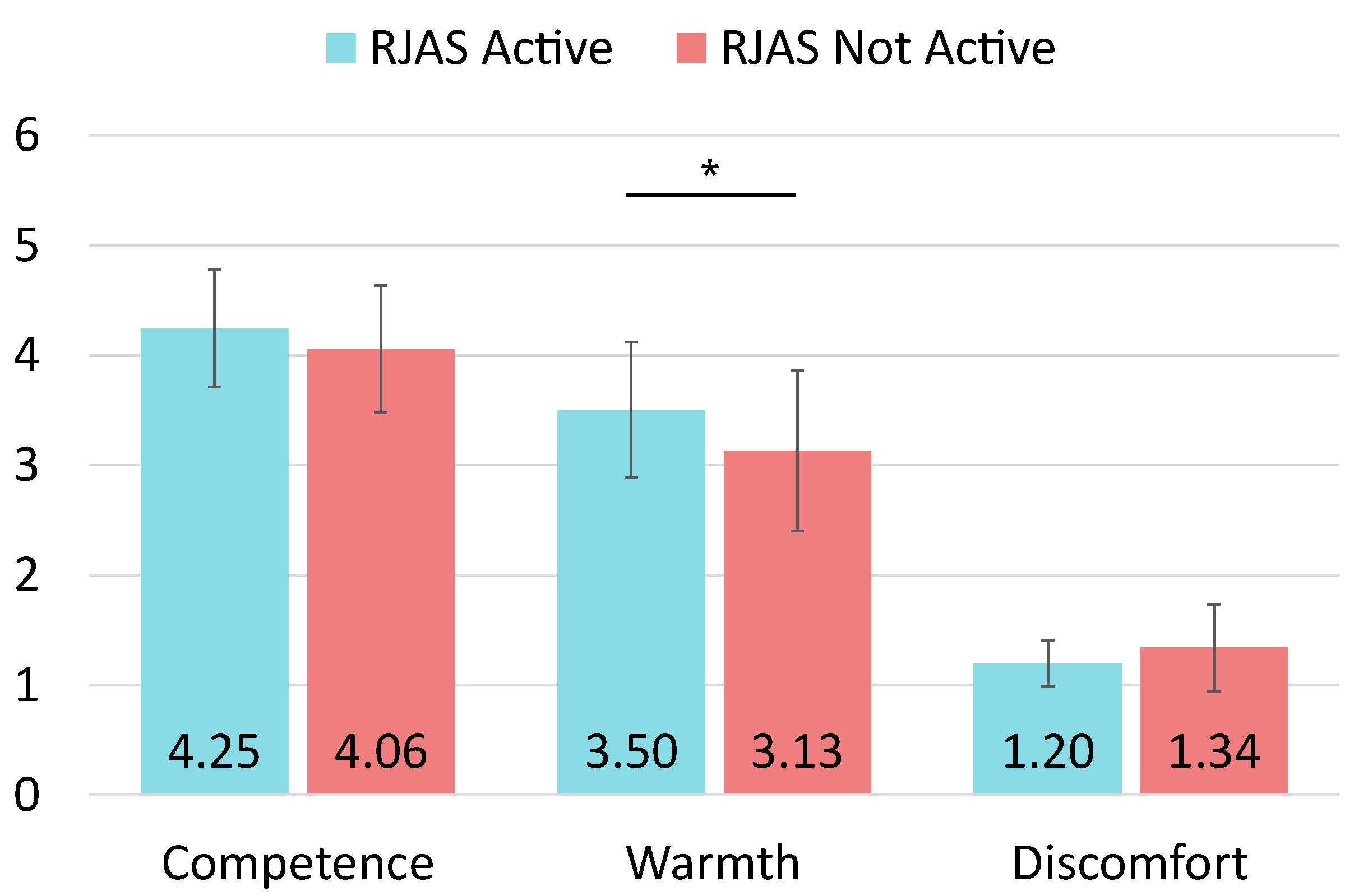

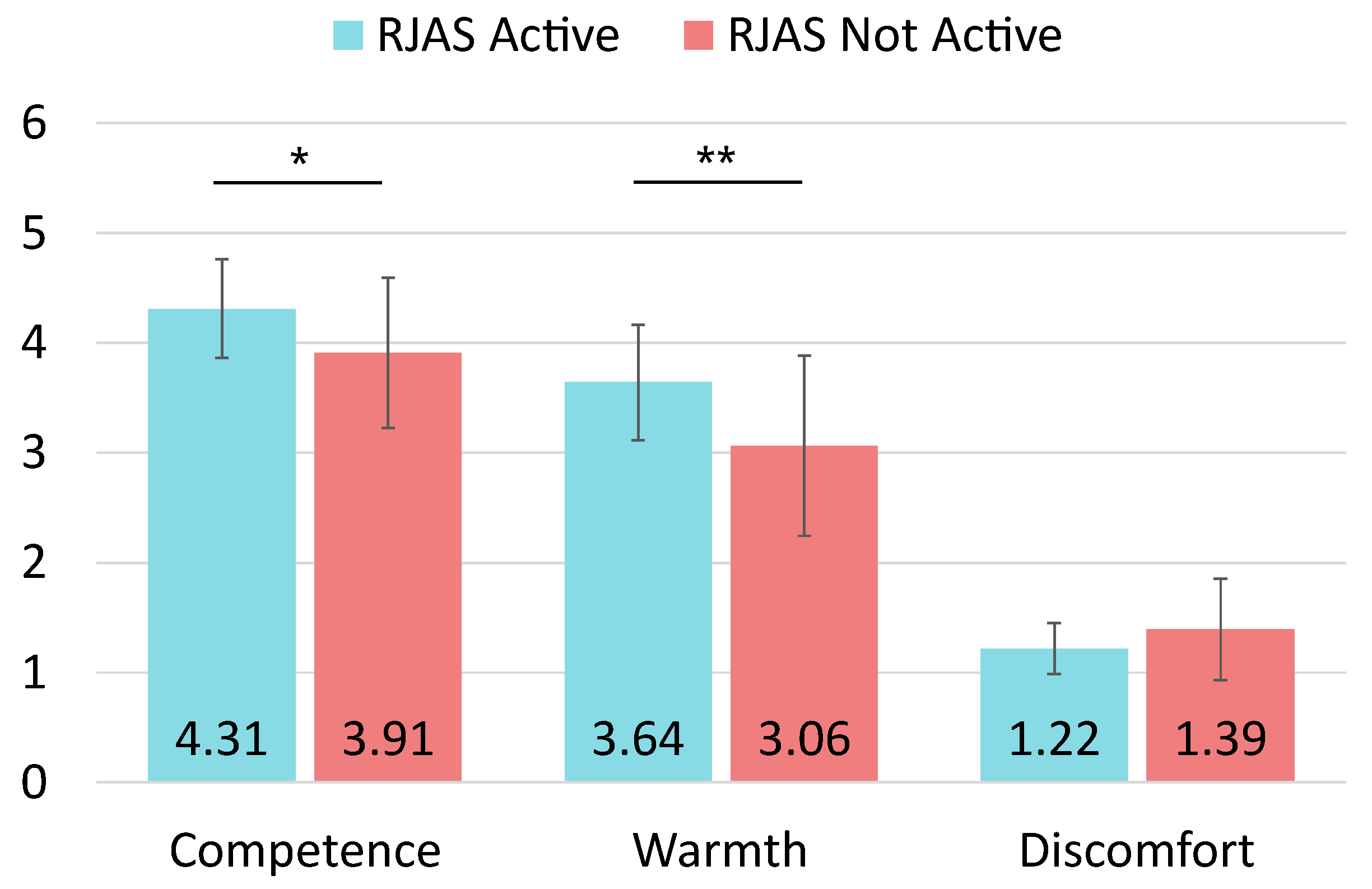

6.1. Quantitative Results

6.2. Qualitative Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Posner, M.I.; Petersen, S.E. The attention system of the human brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1990, 13, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyer, R.S.; Srull, T.K. Human cognition in its social context. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 93, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, H. What We Do and Don’t Know About Joint Attention. Topoi 2024, 43, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinsma, Y.; Koegel, R.L.; Koegel, L.K. Joint attention and children with autism: A review of the literature. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2004, 10, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hours, C.; Recasens, C.; Baleyte, J.M. ASD and ADHD comorbidity: What are we talking about? Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 837424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavens, D.; Racine, T.P. Joint attention in apes and humans: Are humans unique? J. Conscious. Stud. 2009, 16, 240–267. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, N.J.; Lorincz, E.N.; Perrett, D.I.; Oram, M.W.; Baker, C.I. Gaze following and joint attention in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). J. Comp. Psychol. 1997, 111, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundy, P.; Block, J.; Delgado, C.; Pomares, Y.; Van Hecke, A.V.; Parlade, M.V. Individual differences and the development of joint attention in infancy. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 938–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, M.A.; Schultz, A.C. Human–robot interaction: A survey. Found. Trends Hum. Comput. Interact. 2008, 1, 203–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschel, A.; Hortensius, R.; Cross, E.S. Social cognition in the age of human–robot interaction. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, M.; Ono, T.; Ishiguro, H. Physical relation and expression: Joint attention for human-robot interaction. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2003, 50, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.M.; Thomaz, A.L. Joint attention in human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 2010 AAAI Fall Symposium Series, Arlington, VA, USA, 11–13 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, F.; Hafner, V.V. The challenges of joint attention. Interact. Stud. 2006, 7, 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, B.L.; Fitzpatrick, R.C. The vestibular system. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, R583–R586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpinella, C.M.; Wyman, A.B.; Perez, M.A.; Stroessner, S.J. The robotic social attributes scale (RoSAS) development and validation. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Vienna, Austria, 6–9 March 2017; pp. 254–262. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. In Social Cognition; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 162–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T. Stereotype content: Warmth and competence endure. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoforakos, L.; Gallucci, A.; Surmava-Große, T.; Ullrich, D.; Diefenbach, S. Can robots earn our trust the same way humans do? A systematic exploration of competence, warmth, and anthropomorphism as determinants of trust development in HRI. Front. Robot. 2021, 8, 640444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 40, 61–149. [Google Scholar]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Schepers, J.; Flavián, C. Examining the effects of robots’ physical appearance, warmth, and competence in frontline services: The Humanness-Value-Loyalty model. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 2357–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, K.R.; Bai, X.; Fiske, S.T. Warmth and competence in human-agent cooperation. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2024, 38, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; Arriaga, P.; Correia, F.; Paiva, A. The stereotype content model applied to human-robot interactions in groups. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Daegu, Republic of Korea, 11–14 March 2019; pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bartneck, C.; Croft, E.; Kulic, D. Measurement instruments for the anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability, perceived intelligence, and perceived safety of robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2009, 1, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Watson, A.M.; Larson, L.E.; Lauharatanahirun, N.; DeChurch, L.A.; Contractor, N.S. Social perception in Human-AI teams: Warmth and competence predict receptivity to AI teammates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 145, 107765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, T.; Russwinkel, N. Talking Like One of Us: Effects of Using Regional Language in a Humanoid Social Robot. In International Conference on Social Robotics; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Talsma, D.; Senkowski, D.; Soto-Faraco, S.; Woldorff, M.G. The multifaceted interplay between attention and multisensory integration. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.; Dunham, P.J.; Dunham, P. Joint Attention: Its Origins and Role in Development; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, L.J.; Edwards, S.G.; Bayliss, A.P. From gaze perception to social cognition: The shared-attention system. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompatsiari, K.; Bossi, F.; Wykowska, A. Eye contact during joint attention with a humanoid robot modulates oscillatory brain activity. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2021, 16, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scassellati, B. Theory of mind for a humanoid robot. Auton. Robot. 2002, 12, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saran, A.; Majumdar, S.; Short, E.S.; Thomaz, A.; Niekum, S. Human gaze following for human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 8615–8621. [Google Scholar]

- Scassellati, B. Imitation and mechanisms of joint attention: A developmental structure for building social skills on a humanoid robot. In International Workshop on Computation for Metaphors, Analogy, and Agents; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 176–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M.; Tani, J. Joint attention between a humanoid robot and users in imitation game. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL), La Jolla, CA, USA, 20–22 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Skantze, G.; Hjalmarsson, A.; Oertel, C. Turn-taking, feedback and joint attention in situated human–robot interaction. Speech Commun. 2014, 65, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M. Components of visual orienting. Atten. Perform. Control Lang. Process. Erlbaum 1984, 32, 531–556. [Google Scholar]

- Sumioka, H.; Hosoda, K.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Asada, M. Acquisition of joint attention through natural interaction utilizing motion cues. Adv. Robot. 2007, 21, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, C.M.; Thomaz, A.L. Effects of responding to, initiating and ensuring joint attention in human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 2011 Ro-Man, Atlanta, GA, USA, 31 July–3 August 2011; pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Diana, C.; Thomaz, A.L. The shape of simon: Creative design of a humanoid robot shell. In Proceedings of the CHI’11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–11 May 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: NewYork, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.; Oertel, C.; Fermoselle, L.; Mendelson, J.; Gustafson, J. Responsive joint attention in human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 1080–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, C.; Skantze, G. Knowing where to look: A planning-based architecture to automate the gaze behavior of social robots. In Proceedings of the 2022 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Napoli, Italy, 29 August–2 September 2022; pp. 1201–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Woertman, S.E. Joint Attention in Human-Robot Interaction. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Borji, A.; Itti, L. State-of-the-art in visual attention modeling. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 35, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Villarroya, S.; Castillo, J.C.; Fernández-Rodicio, E.; Salichs, M.A. A bio-inspired exogenous attention-based architecture for social robots. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salichs, M.A.; Castro-González, Á.; Salichs, E.; Fernández-Rodicio, E.; Maroto-Gómez, M.; Gamboa-Montero, J.J.; Marques-Villarroya, S.; Castillo, J.C.; Alonso-Martín, F.; Malfaz, M. Mini: A new social robot for the elderly. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2020, 12, 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Driver, J. Audiovisual links in exogenous covert spatial orienting. Percept. Psychophys. 1997, 59, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, K.; Sarkar, S. Saliency in images and video: A brief survey. IET Comput. Vis. 2012, 6, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Yan, L.; Wu, K.; Niu, J. Effects of Voice and Lighting Color on the Social Perception of Home Healthcare Robots. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.; Kraus, J.; Baumann, M.; Minker, W. Effects of Gender Stereotypes on Trust and Likability in Spoken Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), Miyazaki, Japan, 7–12 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Users | Joint Attention Mechanisms | Metrics | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imai et al. [11] | 20 | Eye Contact, Pointing gestures | Achievement of JA | Video |

| Huang and Thomaz [37] | 20 | Pointing gestures, Gaze-following | Task performance, Engagement | Video, Custom questionnaire |

| Skantze et al. [34] | 24 | Turn-taking, Gaze-following | Task performance, Drawing activity | Quantitative data, Custom questionnaire |

| Pereira et al. [39] | 22 | Gaze-following | Social presence | SPI questionnaire |

| Mishra and Skantze [40] | 26 | Turn-taking, Gaze-following | Awareness, Human likeness, Intimacy | Custom questionnaire |

| Woertman [41] | 40 | Gaze-following | Trust | Custom questionnaire |

| Ours | 91 | Gaze-following, Imitation, Turn-taking | Competence, Warmth, Discomfort | RoSAS, User feedback |

| Source | Duration | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left speaker | 2 s | Auditory | Sound of a drum |

| Right speaker | 5 s | Auditory | Sound of bells |

| Monitor | Until round finishes | Visual | Animation of a moving vehicle |

| Left speaker | 1 s (twice) | Auditory | Sound of breaking glass |

| Monitor | Until round finishes | Visual | A chase between a coyote and a rabbit |

| Right speaker | 5 s | Auditory | Sound of an alarm clock |

| Population | Dimension | Condition | N | Average | SD | p | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Competence | Active | 46 | 4.246 | 0.533 | >0.05 | 0.479 |

| Inactive | 45 | 4.059 | 0.579 | ||||

| Warmth | Active | 44 | 3.504 | 0.618 | 0.012 | 0.819 | |

| Inactive | 44 | 3.133 | 0.729 | ||||

| Discomfort | Active | 43 | 1.198 | 0.210 | >0.05 | 0.150 | |

| Inactive | 45 | 1.341 | 0.397 | ||||

| Men | Competence | Active | 27 | 4.309 | 0.450 | 0.019 | 0.772 |

| Inactive | 20 | 3.908 | 0.681 | ||||

| Warmth | Active | 25 | 3.640 | 0.524 | 0.007 | 0.876 | |

| Inactive | 19 | 3.061 | 0.821 | ||||

| Discomfort | Active | 26 | 1.218 | 0.230 | >0.05 | 0.115 | |

| Inactive | 20 | 1.392 | 0.460 | ||||

| Women | Competence | Active | 19 | 4.158 | 0.635 | >0.05 | 0.105 |

| Inactive | 24 | 4.222 | 0.419 | ||||

| Warmth | Active | 19 | 3.281 | 0.774 | >0.05 | 0.063 | |

| Inactive | 24 | 3.256 | 0.575 | ||||

| Discomfort | Active | 17 | 1.167 | 0.177 | >0.05 | 0.115 | |

| Inactive | 25 | 1.300 | 0.344 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Martínez, J.; Gamboa-Montero, J.J.; Castillo, J.C.; Castro-González, Á. Analyzing the Impact of Responding to Joint Attention on the User Perception of the Robot in Human-Robot Interaction. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics9120769

García-Martínez J, Gamboa-Montero JJ, Castillo JC, Castro-González Á. Analyzing the Impact of Responding to Joint Attention on the User Perception of the Robot in Human-Robot Interaction. Biomimetics. 2024; 9(12):769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics9120769

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Martínez, Jesús, Juan José Gamboa-Montero, José Carlos Castillo, and Álvaro Castro-González. 2024. "Analyzing the Impact of Responding to Joint Attention on the User Perception of the Robot in Human-Robot Interaction" Biomimetics 9, no. 12: 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics9120769

APA StyleGarcía-Martínez, J., Gamboa-Montero, J. J., Castillo, J. C., & Castro-González, Á. (2024). Analyzing the Impact of Responding to Joint Attention on the User Perception of the Robot in Human-Robot Interaction. Biomimetics, 9(12), 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics9120769