Influence of Prosthetic Material Properties and Implant Number on Stress Distribution in Implant–Bone Systems Under Bruxism Loading: A Finite Element Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

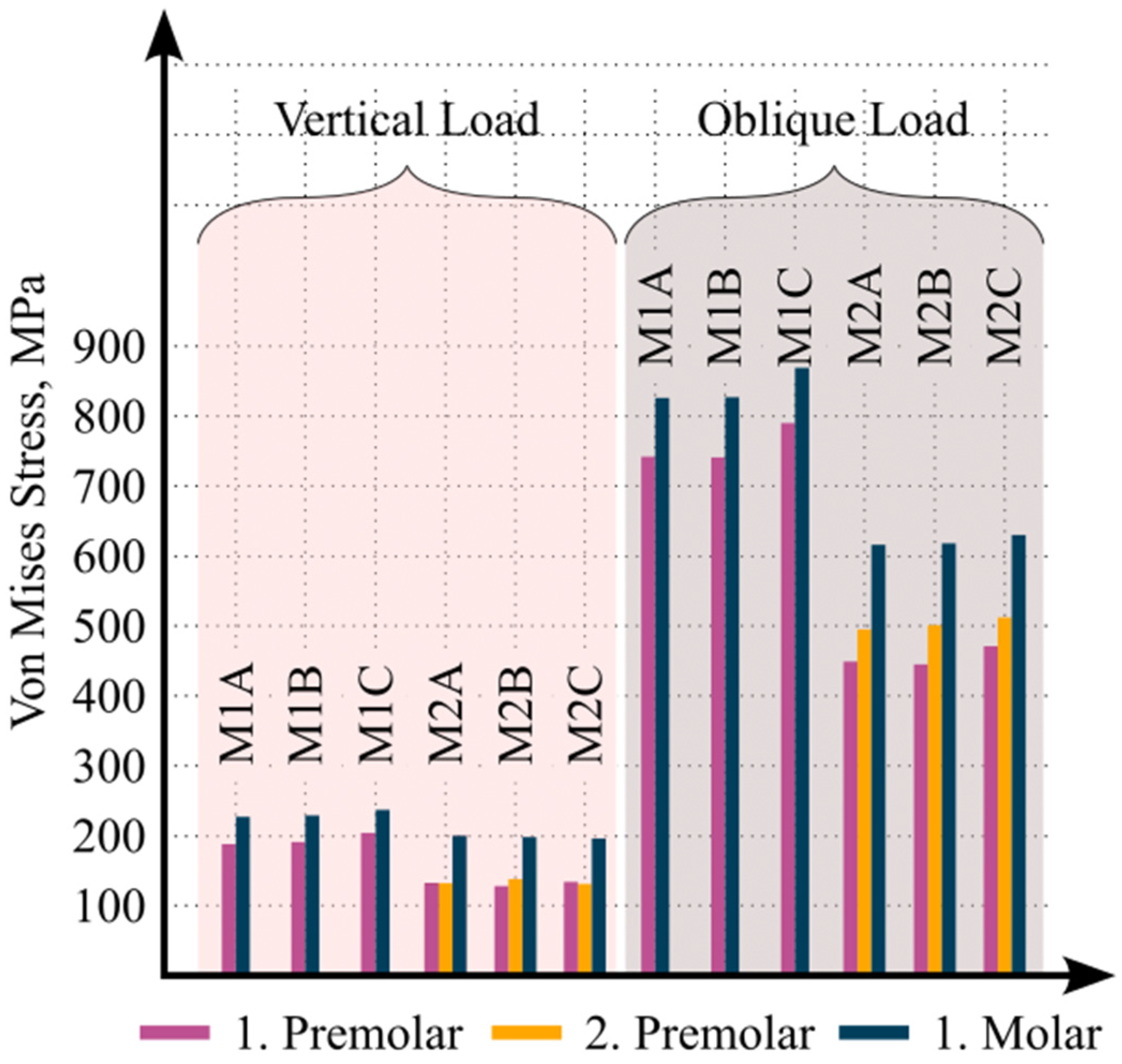

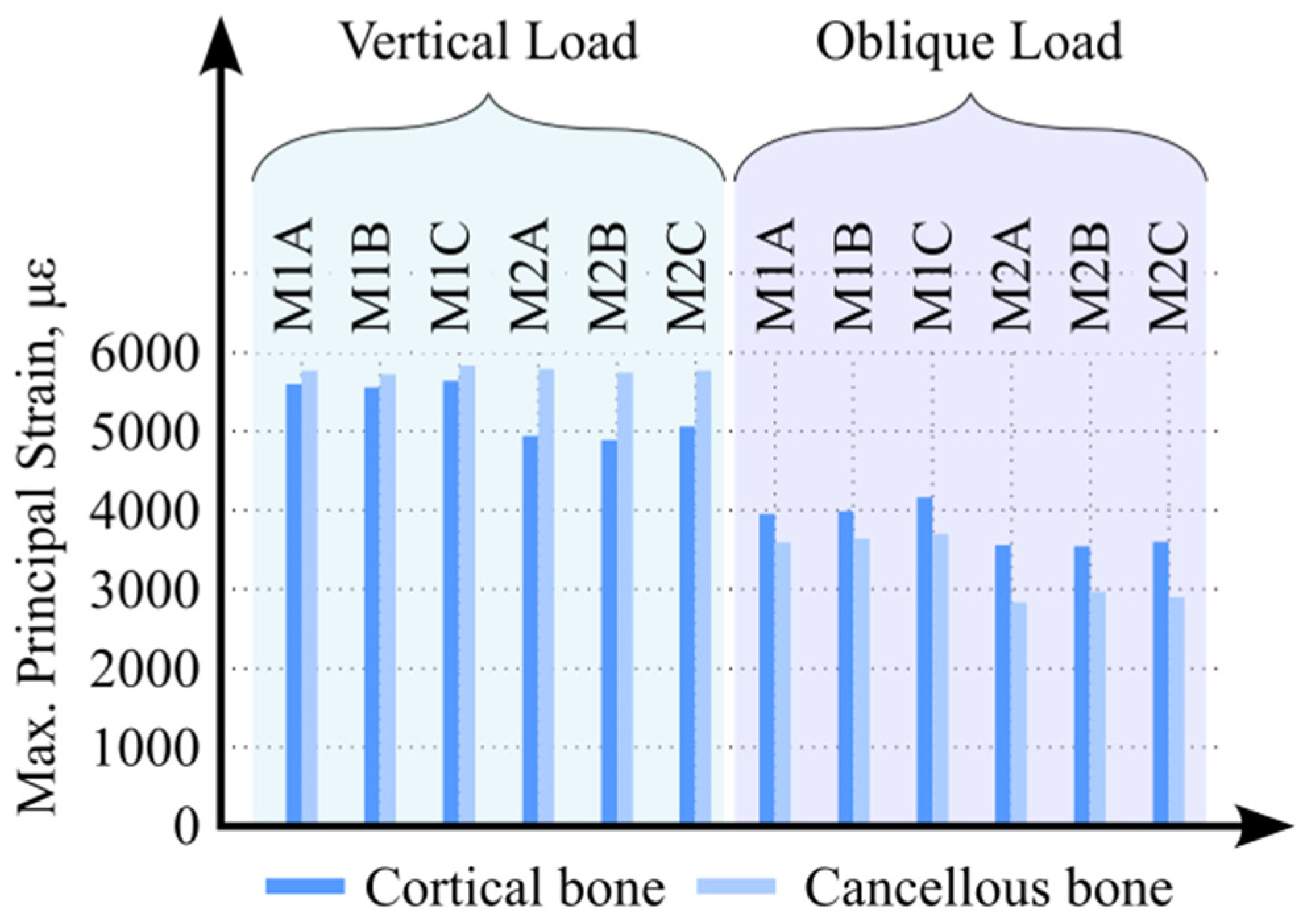

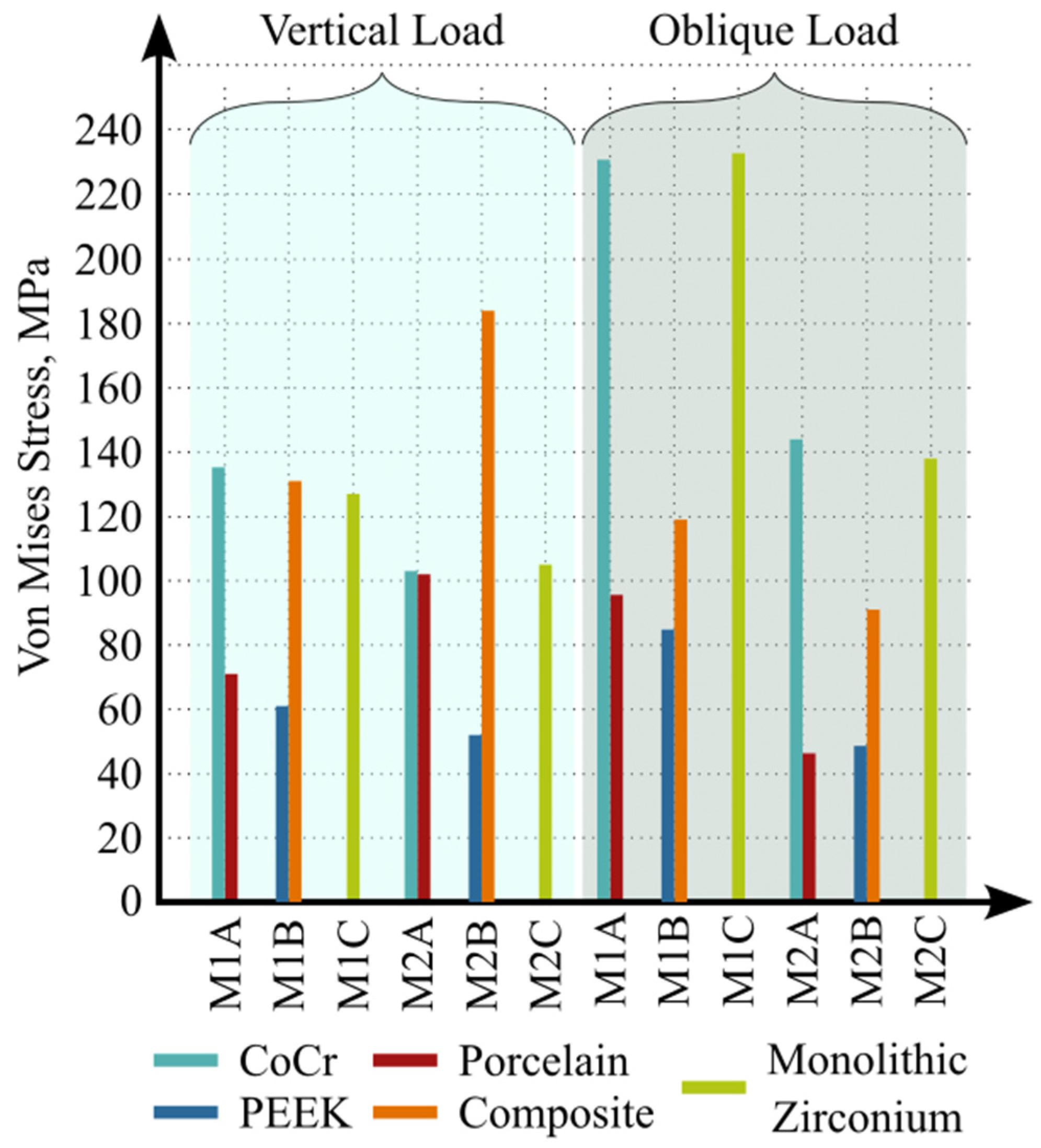

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satoh, T.; Maeda, Y.; Komiyama, Y. Biomechanical Rationale for Intentionally Inclined Implants in the Posterior Mandible Using 3D Finite Element Analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2005, 20, 533–539. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.-T.; Fu, J.-H.; Al-Hezaimi, K.; Wang, H.-L. Biomechanical Implant Treatment Complications: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies of Implants with at Least 1 Year of Functional Loading. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2012, 27, 894–904. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne, G.J.; Khoury, S.; Abe, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Raphael, K. Bruxism Physiology and Pathology: An Overview for Clinicians. J. Oral Rehabil. 2008, 35, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlberg, J.; Savolainen, A.; Rantala, M.; Lindholm, H.; Könönen, M. Reported Bruxism and Biopsychosocial Symptoms: A Longitudinal Study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2004, 32, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiamonte, T.; Abbate, M.F.; Pizzarello, F.; Lozada, J.; James, R. The Experimental Verification of the Efficacy of Finite Element Modeling to Dental Implant Systems. J. Oral Implantol. 1996, 22, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, A.; Consani, R.L.X.; Mesquita, M.F.; dos Santos, M.B.F. Effect of Framework Material and Vertical Misfit on Stress Distribution in Implant-Supported Partial Prosthesis under Load Application: 3-D Finite Element Analysis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2013, 71, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, A.; Consani, R.L.X.; Mesquita, M.F.; dos Santos, M.B.F. Stress Distribution in Fixed-Partial Prosthesis and Peri-Implant Bone Tissue with Different Framework Materials and Vertical Misfit Levels: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. J. Oral Sci. 2013, 55, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriç, G.; Erkmen, E.; Kurt, A.; Tunç, Y.; Eser, A. Influence of Prosthesis Type and Material on the Stress Distribution in Bone around Implants: A 3-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. J. Dent. Sci. 2011, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menini, M.; Conserva, E.; Tealdo, T.; Bevilacqua, M.; Pera, F.; Signori, A.; Pera, P. Shock Absorption Capacity of Restorative Materials for Dental Implant Prostheses: An in Vitro Study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2013, 26, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo Nobre, M.; Moura Guedes, C.; Almeida, R.; Silva, A. Poly-Ether-Ether-Ketone and Implant Dentistry: The Future of Mimicking Natural Dentition Is Now! Polym. Int. 2021, 70, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Sonwal, S.; Sharma, R.P.; Saini, S.; Huh, Y.S.; Brambilla, E.; Ionescu, A.C. Ranking Analysis of Tribological, Mechanical, and Thermal Properties of Nano Hydroxyapatite Filled Dental Restorative Composite Materials Using the R-Method. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid-Verdejo, R.; Chávez Farías, C.; Martínez-Pozas, O.; Meléndez Oliva, E.; Cuenca-Zaldívar, J.N.; Ardizone García, I.; Martínez Orozco, F.J.; Sánchez Romero, E.A. Instrumental Assessment of Sleep Bruxism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2024, 74, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assiri, H.A.; Almuawi, L.F.; Asiri, B.A.; Abumelha, S.T.; Alahmari, R.M.; Hameed, M.S.; Egido-Moreno, S.; López-López, J. Bruxism Treatment Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2025, 104, e46247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.-B.; Cho, W.-T.; Park, D.-H.; Hwang, S.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Yun, M.-J.; Jeong, C.-M.; Huh, J.-B. Comparison of Fit and Trueness of Zirconia Crowns Fabricated by Different Combinations of Open CAD-CAM Systems. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2023, 15, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcinelli, C.; Valente, F.; Vasta, M.; Traini, T. Finite Element Analysis in Implant Dentistry: State of the Art and Future Directions. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó-Navés, O.; Medina-Galvez, R.; Marimon, X.; Ferrer, M.; Figueras-Álvarez, Ó.; Cabratosa-Termes, J. A 3D Finite Element Analysis Model of Single Implant-Supported Prosthesis under Dynamic Impact Loading for Evaluation of Stress in the Crown, Abutment and Cortical Bone Using Different Rehabilitation Materials. Materials 2021, 14, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevimay, M.; Turhan, F.; Kiliçarslan, M.A.; Eskitascioglu, G. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis of the Effect of Different Bone Quality on Stress Distribution in an Implant-Supported Crown. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2005, 93, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, B.A.; Gultekin, P.; Yalcin, S. Application of Finite Element Analysis in Implant Dentistry. In Finite Element Analysis—New Trends and Developments; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-0769-9. [Google Scholar]

- Eskitascioglu, G.; Usumez, A.; Sevimay, M.; Soykan, E.; Unsal, E. The Influence of Occlusal Loading Location on Stresses Transferred to Implant-Supported Prostheses and Supporting Bone: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2004, 91, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourya, A.; Nahar, R.; Mishra, S.K.; Chowdhary, R. Stress Distribution around Different Abutments on Titanium and CFR-PEEK Implant with Different Prosthetic Crowns under Parafunctional Loading: A 3D FEA Study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2021, 11, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-L.; Chang, Y.-H.; Liu, P.-R. Multi-Factorial Analysis of a Cusp-Replacing Adhesive Premolar Restoration: A Finite Element Study. J. Dent. 2008, 36, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Tabares, S.; Stenport, V.F.; Hjalmarsson, L.; Johansson, C.B. Limited Effect of Cement Material on Stress Distribution of a Monolithic Translucent Zirconia Crown: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 31, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, E.; Korkmaz, İ.H. Effect of Different Design of Abutment and Implant on Stress Distribution in 2 Implants and Peripheral Bone: A Finite Element Analysis Study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 664.e1–664.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörn, D.; Kohorst, P.; Besdo, S.; Rücker, M.; Stiesch, M.; Borchers, L. Influence of Lubricant on Screw Preload and Stresses in a Finite Element Model for a Dental Implant. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.S.; Verri, F.R.; Lemos, C.A.A.; Martins, C.M.; Pellizzer, E.P.; de Souza Batista, V.E. Biomechanical Effect of an Occlusal Device for Patients with an Implant-Supported Fixed Dental Prosthesis under Parafunctional Loading: A 3D Finite Element Analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 223.e1–223.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcato, L.B.; Pellizzer, E.P.; Verri, F.R.; Falcón-Antenucci, R.M.; Santiago Júnior, J.F.; de Faria Almeida, D.A. Influence of Parafunctional Loading and Prosthetic Connection on Stress Distribution: A 3D Finite Element Analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.-H.; Chen, P.-H.; Fok, A.S.L.; Chen, Y.-F. Contact Fracture Test of Monolithic Hybrid Ceramics on Different Substrates for Bruxism. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göre, E.; Evlioğlu, G. Assessment of the Effect of Two Occlusal Concepts for Implant-Supported Fixed Prostheses by Finite Element Analysis in Patients with Bruxism. J. Oral Implantol. 2014, 40, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustrell-Barral, M.; Zamora-Olave, C.; Khoury-Ribas, L.; Rovira-Lastra, B.; Martinez-Gomis, J. Reliability, Reference Values and Factors Related to Maximum Bite Force Measured by the Innobyte System in Healthy Adults with Natural Dentitions. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, D.; Bucci, M.B.; Sabattini, V.B.; Lobbezoo, F. Bruxism: Overview of Current Knowledge and Suggestions for Dental Implants Planning. CRANIO® 2011, 29, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Brouwers, J.E.I.G.; Cune, M.S.; Naeije, M. Dental Implants in Patients with Bruxing Habits. J. Oral Rehabil. 2006, 33, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. Bruxism and Dental Implant Treatment Complications: A Retrospective Comparative Study of 98 Bruxer Patients and a Matched Group. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2017, 28, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Fernandez, E.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, I.; deLlanos-Lanchares, H.; Mauvezin-Quevedo, M.A.; Brizuela-Velasco, A.; Alvarez-Arenal, A. Mandibular Flexure and Peri-Implant Bone Stress Distribution on an Implant-Supported Fixed Full-Arch Mandibular Prosthesis: 3D Finite Element Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8241313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, F.; Aldini, N.N.; Fini, M.; Corinaldesi, G. Immediate Occlusal Loading of Immediately Placed Implants Supporting Fixed Restorations in Completely Edentulous Arches: A 1-Year Prospective Pilot Study. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayan, S.C.; Geckili, O. The Influence of Framework Material on Stress Distribution in Maxillary Complete-Arch Fixed Prostheses Supported by Four Dental Implants: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 24, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, C.A.A.; Verri, F.R.; Noritomi, P.Y.; de Souza Batista, V.E.; Cruz, R.S.; de Luna Gomes, J.M.; de Oliveira Limírio, J.P.J.; Pellizzer, E.P. Biomechanical Evaluation of Different Implant-Abutment Connections, Retention Systems, and Restorative Materials in the Implant-Supported Single Crowns Using 3D Finite Element Analysis. J. Oral Implantol. 2022, 48, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, S.; Değer, Y.; Demirci, F. Evaluation of the Use of PEEK Material in Implant-Supported Fixed Restorations by Finite Element Analysis. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 22, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirandoni, D.; Leal, E.; Weber, B.; Noritomi, P.Y.; Fuentes, R.; Borie, E. Effect of Different Framework Materials in Implant-Supported Fixed Mandibular Prostheses: A Finite Element Analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, e107–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, V.; Ghodsi, S.; Alikhasi, M.; Sahebi, M.; Shamshiri, A.R. Fracture Strength of Three-Unit Implant Supported Fixed Partial Dentures with Excessive Crown Height Fabricated from Different Materials. J. Dent. 2016, 13, 400–406. [Google Scholar]

- Niem, T.; Gonschorek, S.; Wöstmann, B. Investigation of the Damping Capabilities of Different Resin-Based CAD/CAM Restorative Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ö.; Külünk, T.; Külünk, Ş. Influence of Different Implant-Abutment Connections on Stress Distribution in Single Tilted Implants and Peripheral Bone: A Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2018, 29, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammour, S.R.; Ziqi, X.; Ogawa, T.; Yoda, N. Impact of Implant Abutment Connection Designs and Cyclic Loading on Screw Stability in Dental Implants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.-H.; Choi, H. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis of Stress Distribution in Dental Implant Prosthesis and Surrounding Bone Using PEEK Abutments. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shash, Y.H.; El-Wakad, M.T.; El-Dosoky, M.A.A.; Dohiem, M.M. Evaluation of Stresses on Mandible Bone and Prosthetic Parts in Fixed Prosthesis by Utilizing CFR-PEEK, PEKK and PEEK Frameworks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekholm, U.; Gunne, J.; Henry, P.; Higuchi, K.; Lindén, U.; Bergström, C.; van Steenberghe, D. Survival of the Brånemark Implant in Partially Edentulous Jaws: A 10-Year Prospective Multicenter Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 1999, 14, 639–645. [Google Scholar]

- Turnea, M.; Mucileanu, C.; Duduca, I.; Rotariu, M. Mechanical Modeling of the Premolar: Numerical Analysis of Stress Distribution Under Masticatory Forces. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados-Privado, M.; Martínez-Martínez, C.; Gehrke, S.A.; Prados-Frutos, J.C. Influence of Bone Definition and Finite Element Parameters in Bone and Dental Implants Stress: A Literature Review. Biology 2020, 9, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H. Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials, Fourteenth Edition. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwanshi, M.; Jayaswal, P.; Aherwar, A. Mechanical Behaviour Investigation of PEEK Coated Titanium Alloys for Hip Arthroplasty Using Finite Element Analysis. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 56, 2808–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, R.L.; Ferracane, J.; Powers, J.M. Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials, 14th ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cervino, G.; Romeo, U.; Lauritano, F.; Bramanti, E.; Fiorillo, L.; D’Amico, C.; Milone, D.; Laino, L.; Campolongo, F.; Rapisarda, S.; et al. Fem and Von Mises Analysis of OSSTEM® Dental Implant Structural Components: Evaluation of Different Direction Dynamic Loads. Open Dent. J. 2018, 12, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misch, C. Dental Implant Prosthetics, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 978-0-323-07845-0. [Google Scholar]

| Material | Elasticity Modulus [MPa] | Poisson’s Ratios | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titanium (Ti6Al4V) | 110,000 | 0.35 | [17] |

| Cortical bone | 13,700 | 0.3 | [17] |

| Trabecular bone | 1370 | 0.3 | [17] |

| Cobalt–chromium alloy (CoCr) | 218,000 | 0.33 | [18] |

| Feldspathic porcelain | 82,800 | 0.35 | [19] |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | 4000 | 0.37 | [20] |

| Indirect Resin Composite | 50,000 | 0.3 | [21] |

| Monolithic zirconia | 210,000 | 0.3 | [22] |

| Dual-cure resin cement | 6500 | 0.3 | [22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aslan, D.; Korkmaz, İ.H.; Yanıkoğlu, N.; Şensoy, A.T. Influence of Prosthetic Material Properties and Implant Number on Stress Distribution in Implant–Bone Systems Under Bruxism Loading: A Finite Element Study. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020089

Aslan D, Korkmaz İH, Yanıkoğlu N, Şensoy AT. Influence of Prosthetic Material Properties and Implant Number on Stress Distribution in Implant–Bone Systems Under Bruxism Loading: A Finite Element Study. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(2):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020089

Chicago/Turabian StyleAslan, Derya, İsmail Hakkı Korkmaz, Nuran Yanıkoğlu, and Abdullah Tahir Şensoy. 2026. "Influence of Prosthetic Material Properties and Implant Number on Stress Distribution in Implant–Bone Systems Under Bruxism Loading: A Finite Element Study" Biomimetics 11, no. 2: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020089

APA StyleAslan, D., Korkmaz, İ. H., Yanıkoğlu, N., & Şensoy, A. T. (2026). Influence of Prosthetic Material Properties and Implant Number on Stress Distribution in Implant–Bone Systems Under Bruxism Loading: A Finite Element Study. Biomimetics, 11(2), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11020089