Impact of RAMPA Therapy on Nasal Cavity Expansion and Paranasal Drainage: Fluid Mechanics Analysis, CAE Simulation, and a Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

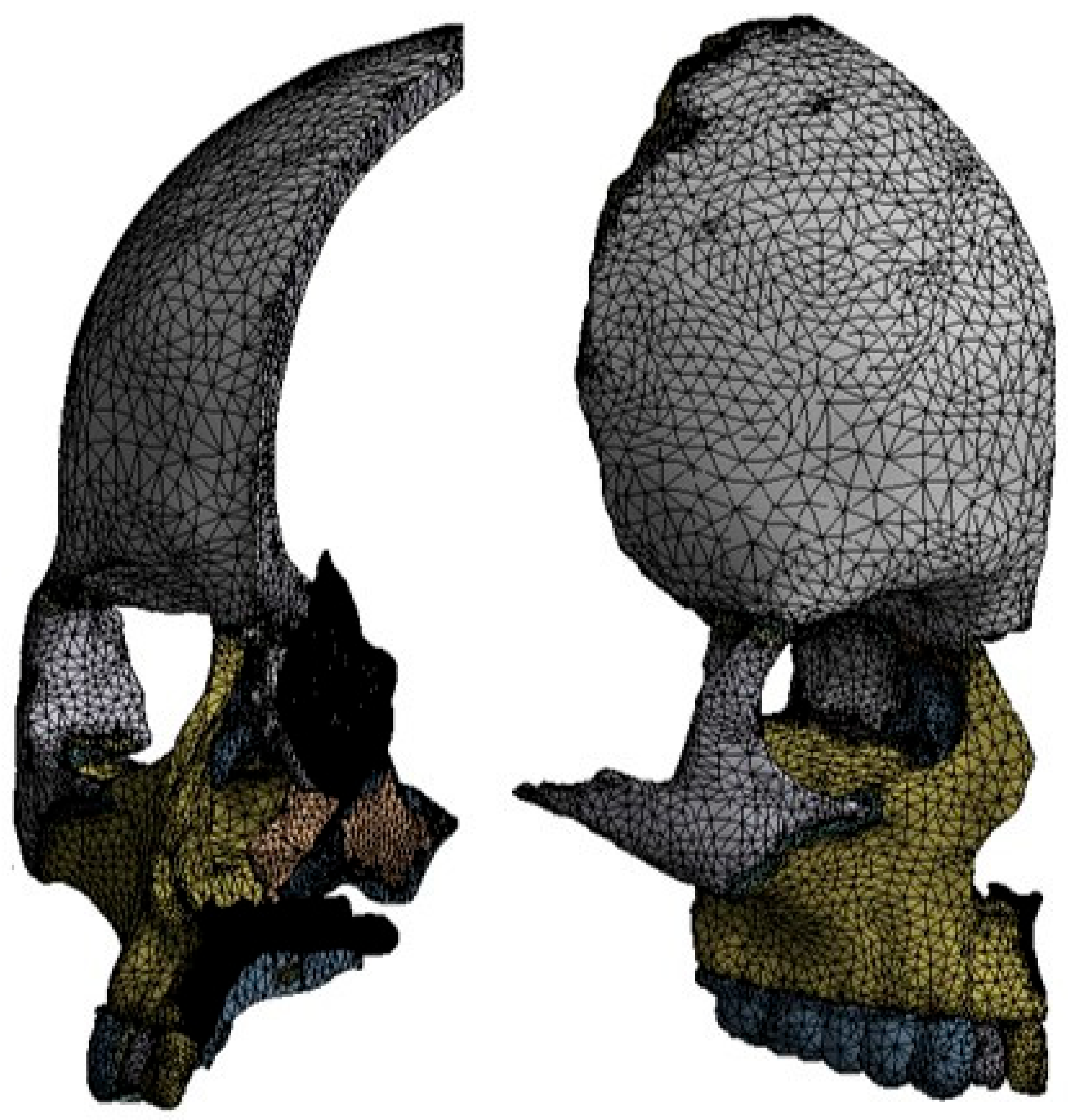

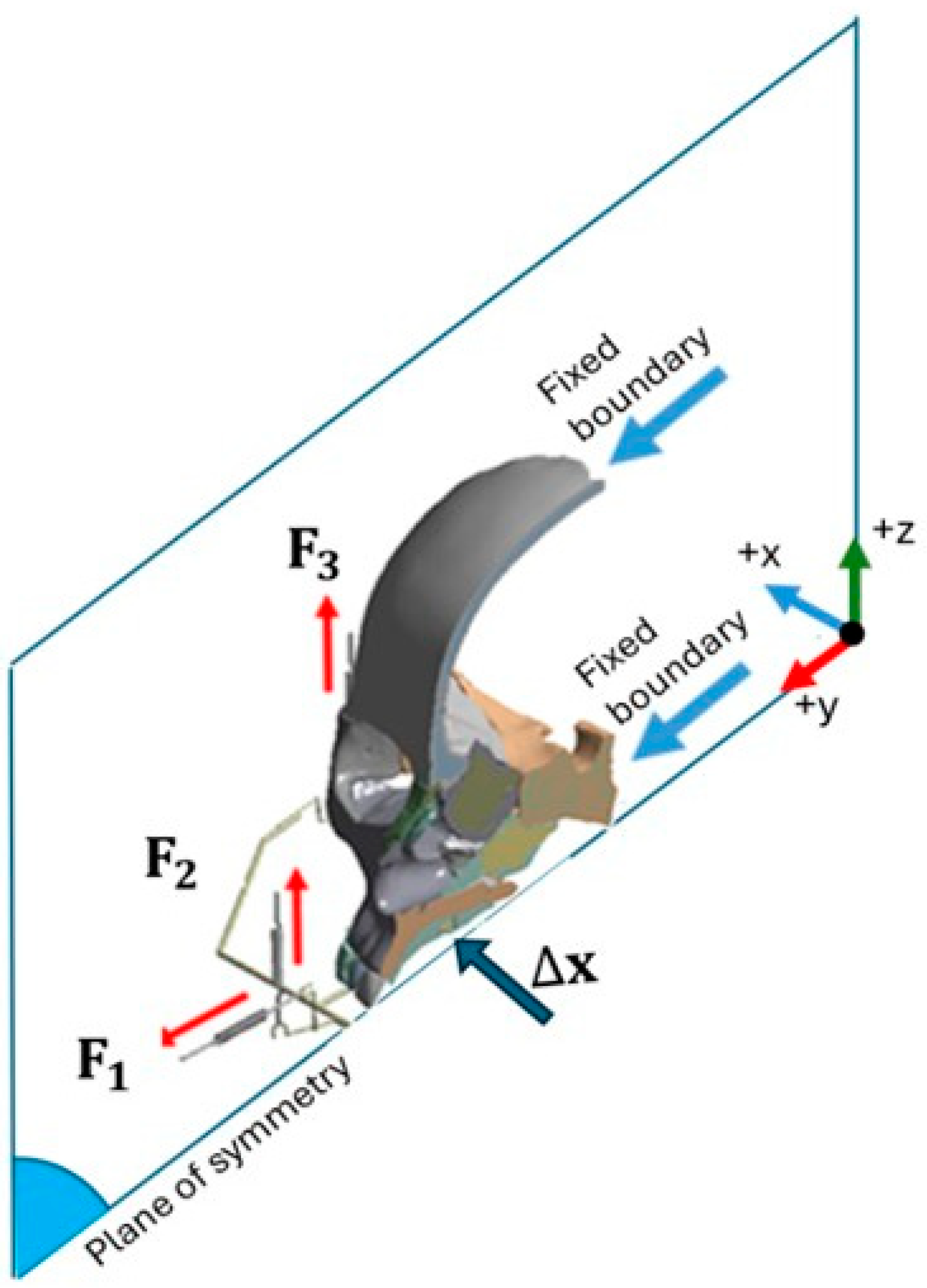

2.1. Finite Element Method

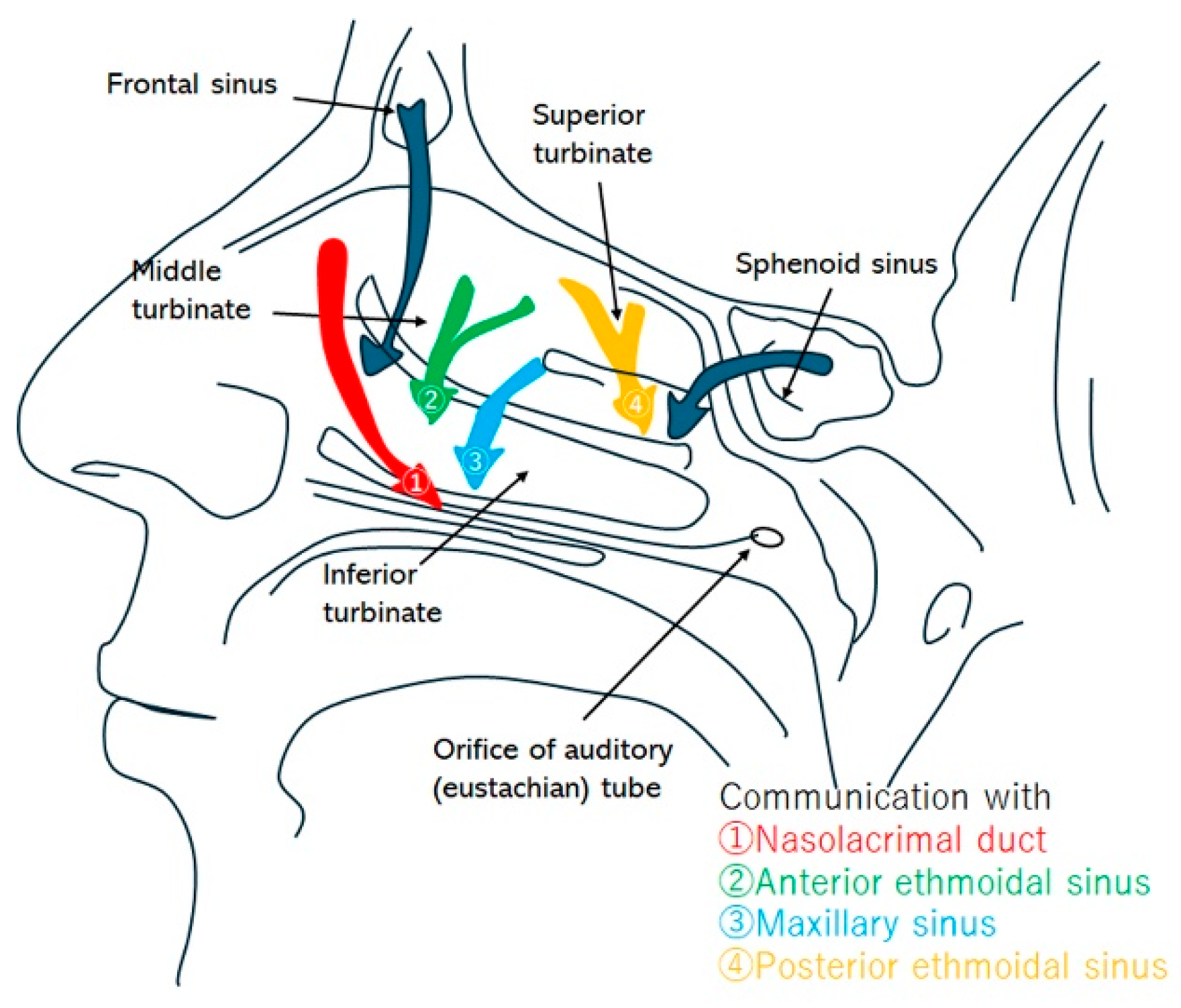

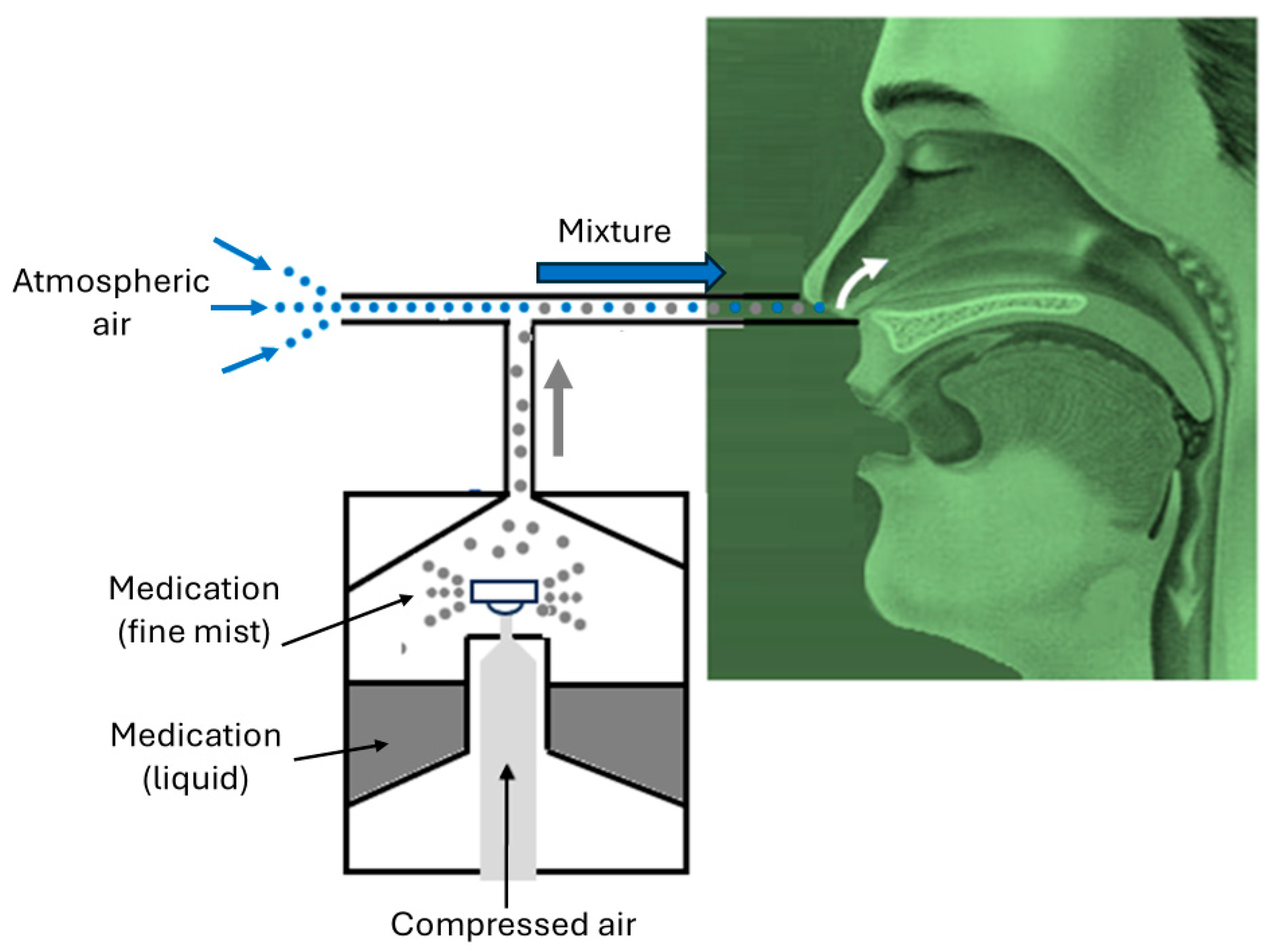

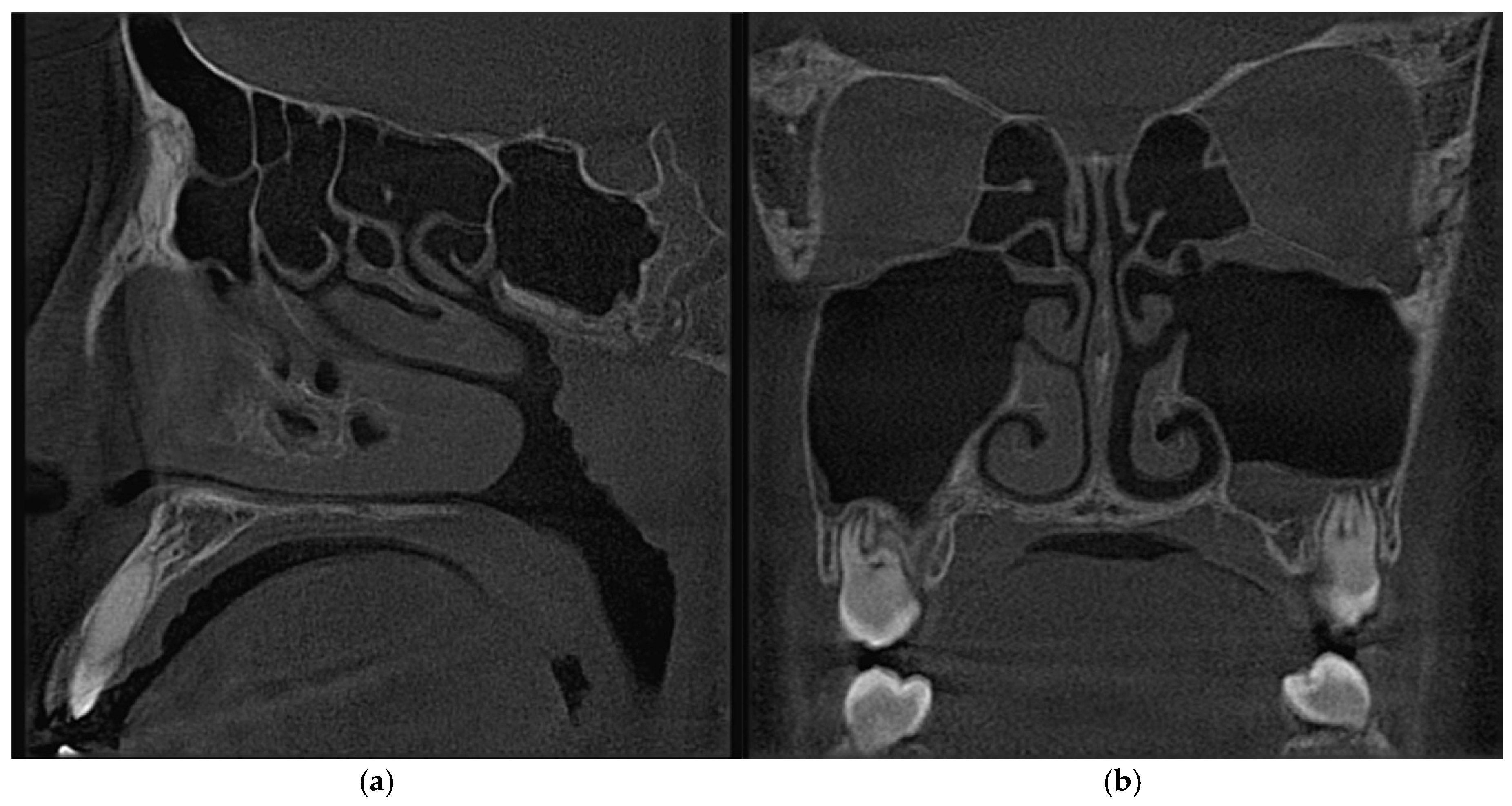

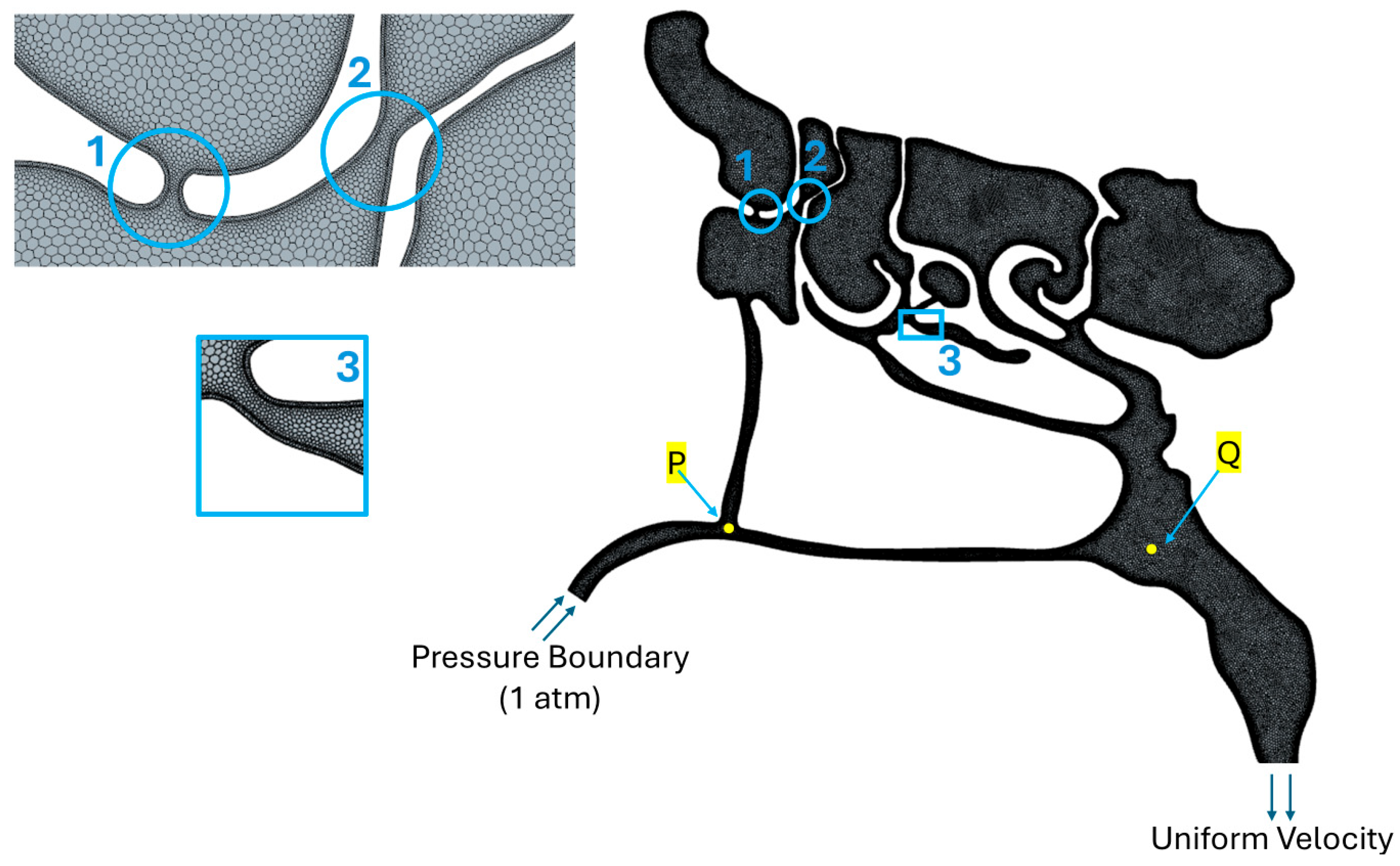

2.2. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations

2.3. Clinical Study

3. Results and Discussions

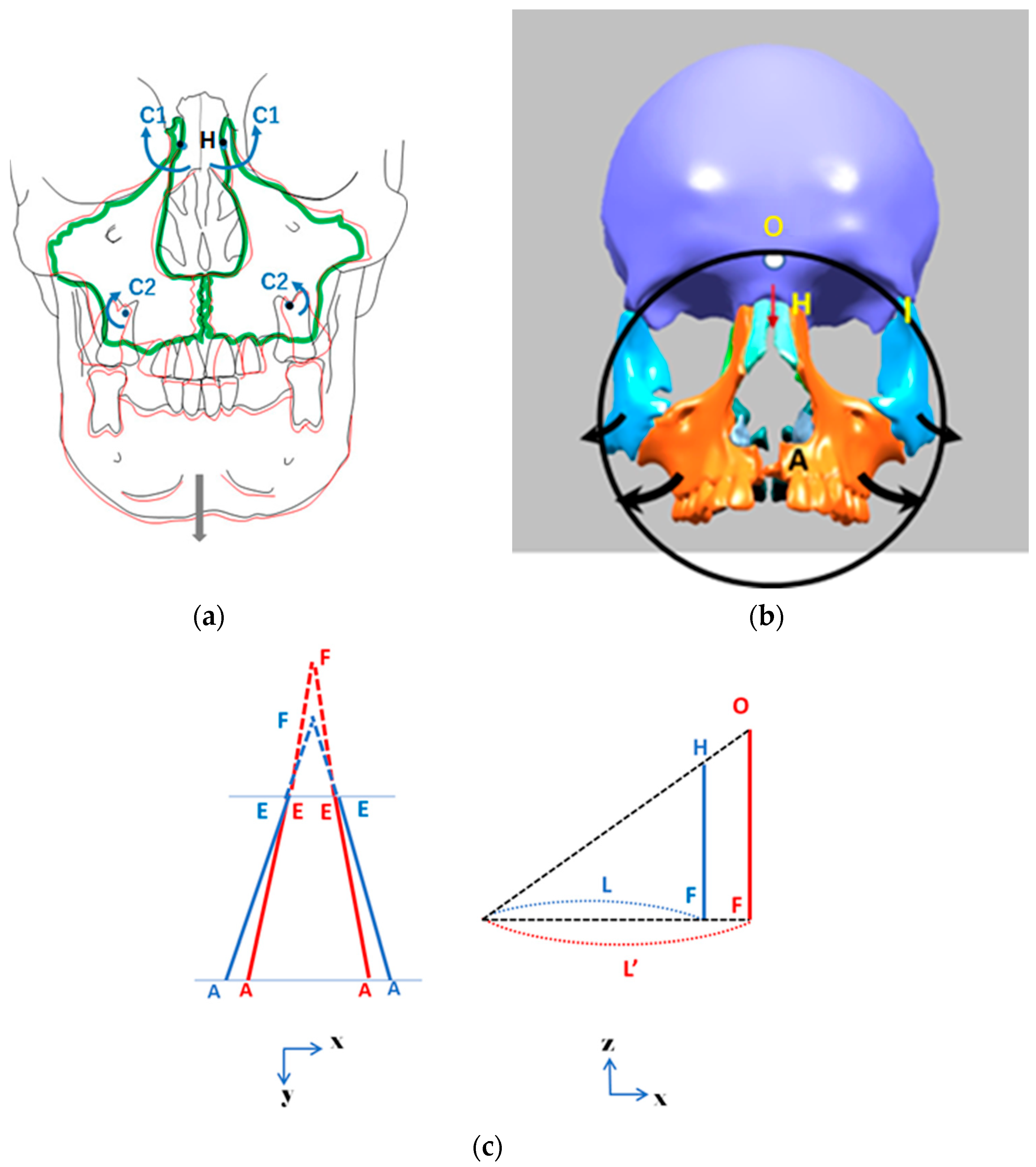

3.1. FEM Analyses of RAMPA’s Impact on Nasal Cavity Expansion

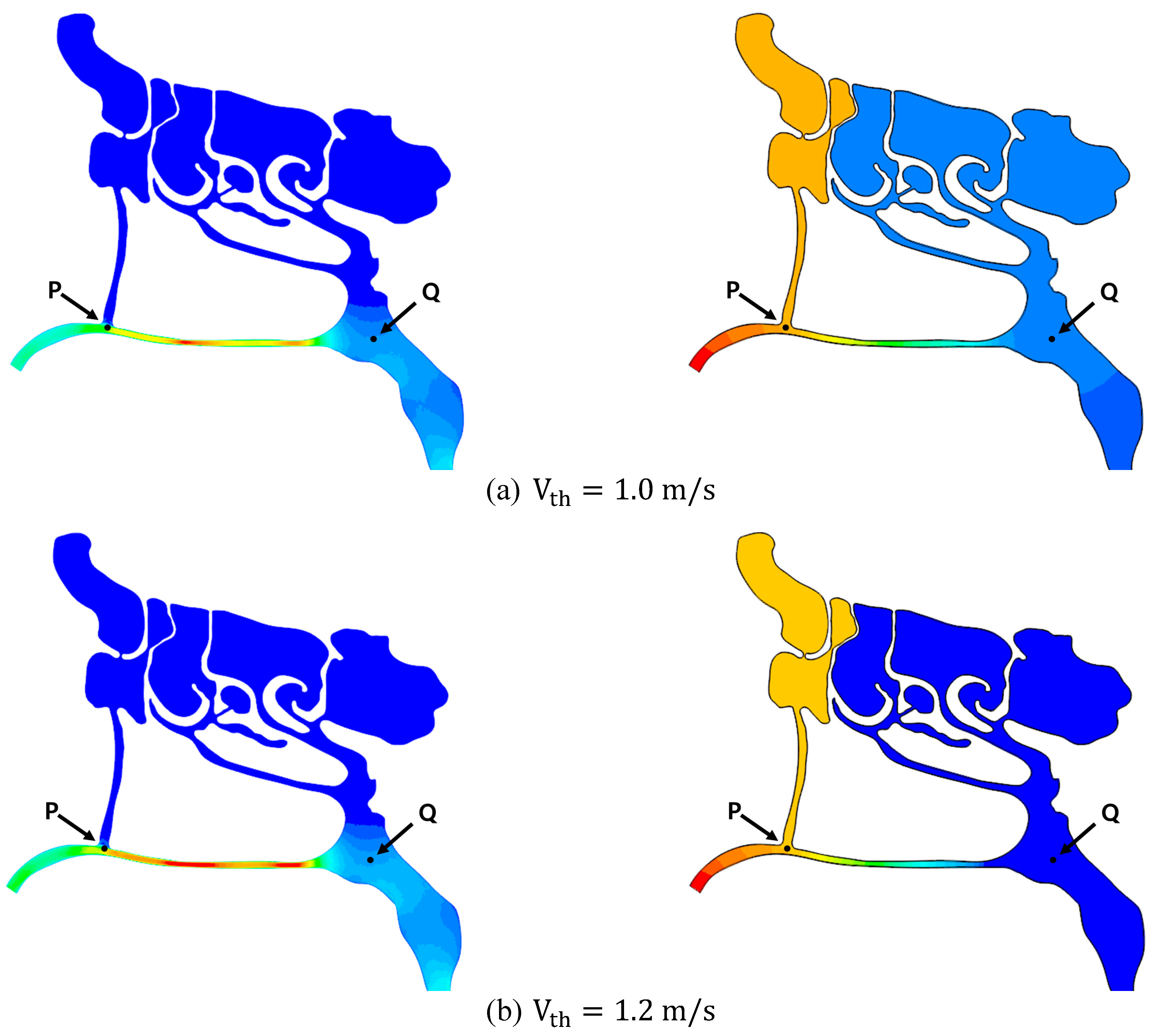

3.2. CFD Simulations of Air and Air–Mucus Transport

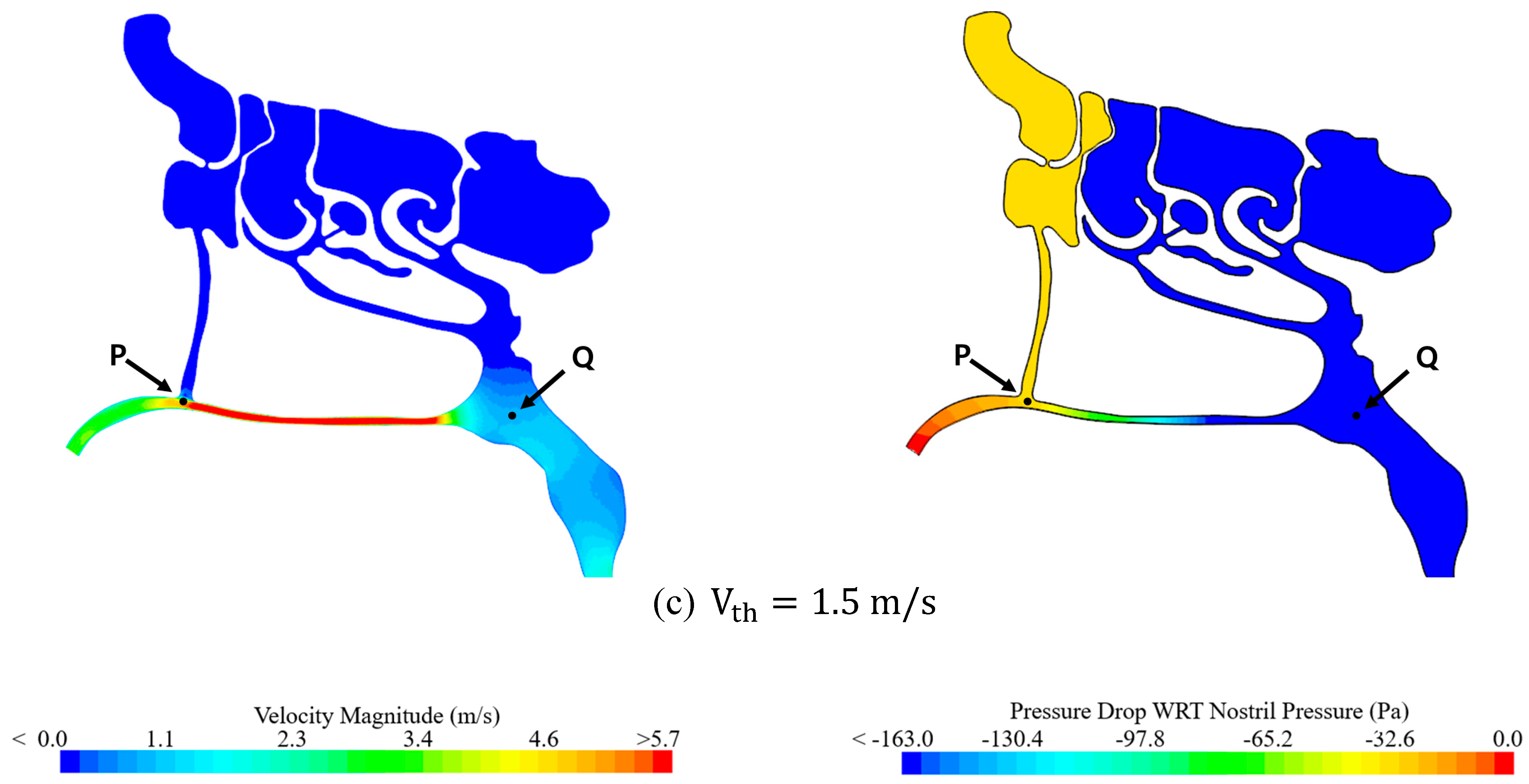

3.2.1. Effect of Air Speed on Local Pressure Inside the Nasal Cavity

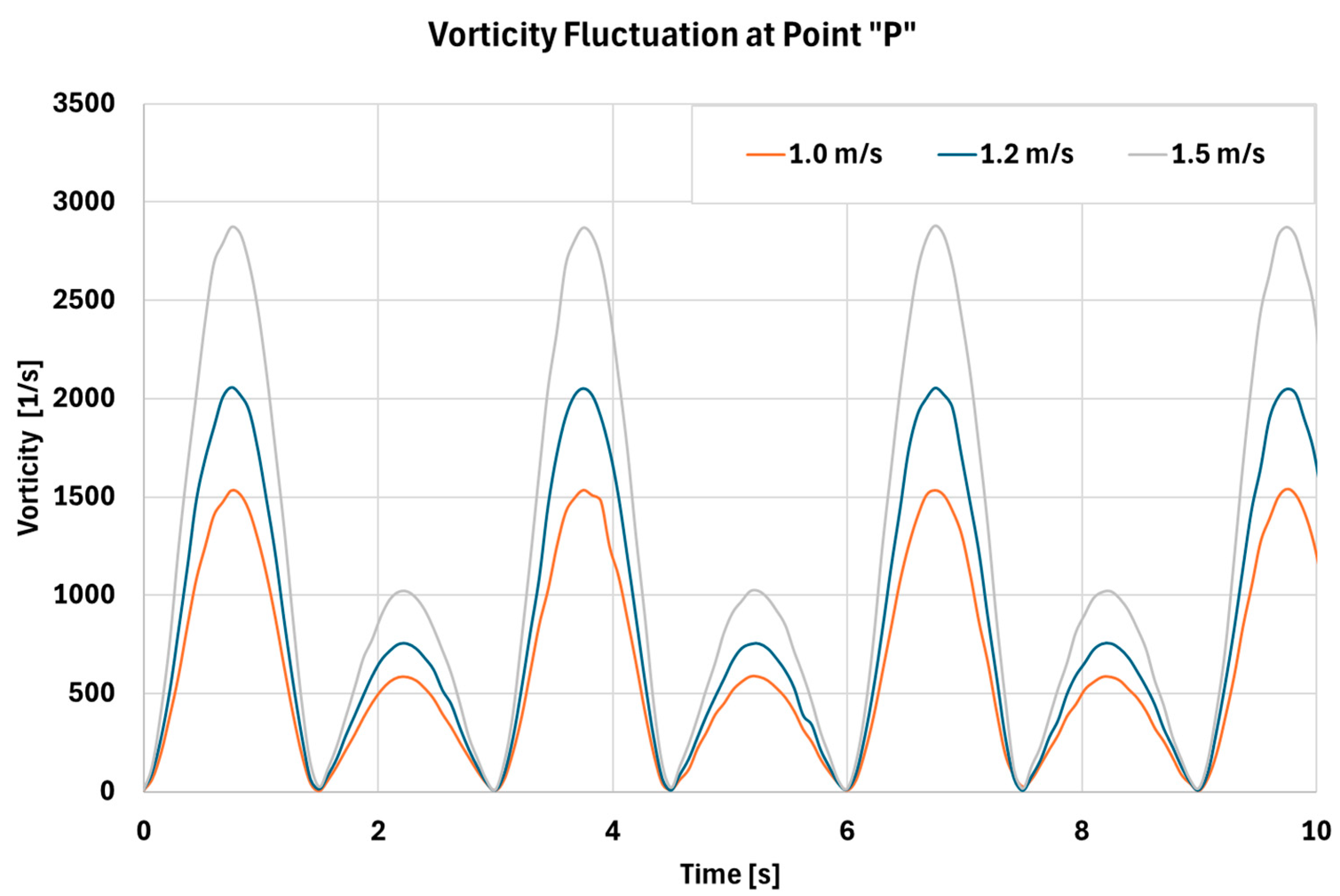

3.2.2. Effect of Sinusoidal Respiration on Flow Fluctuation Inside Nasal Cavity

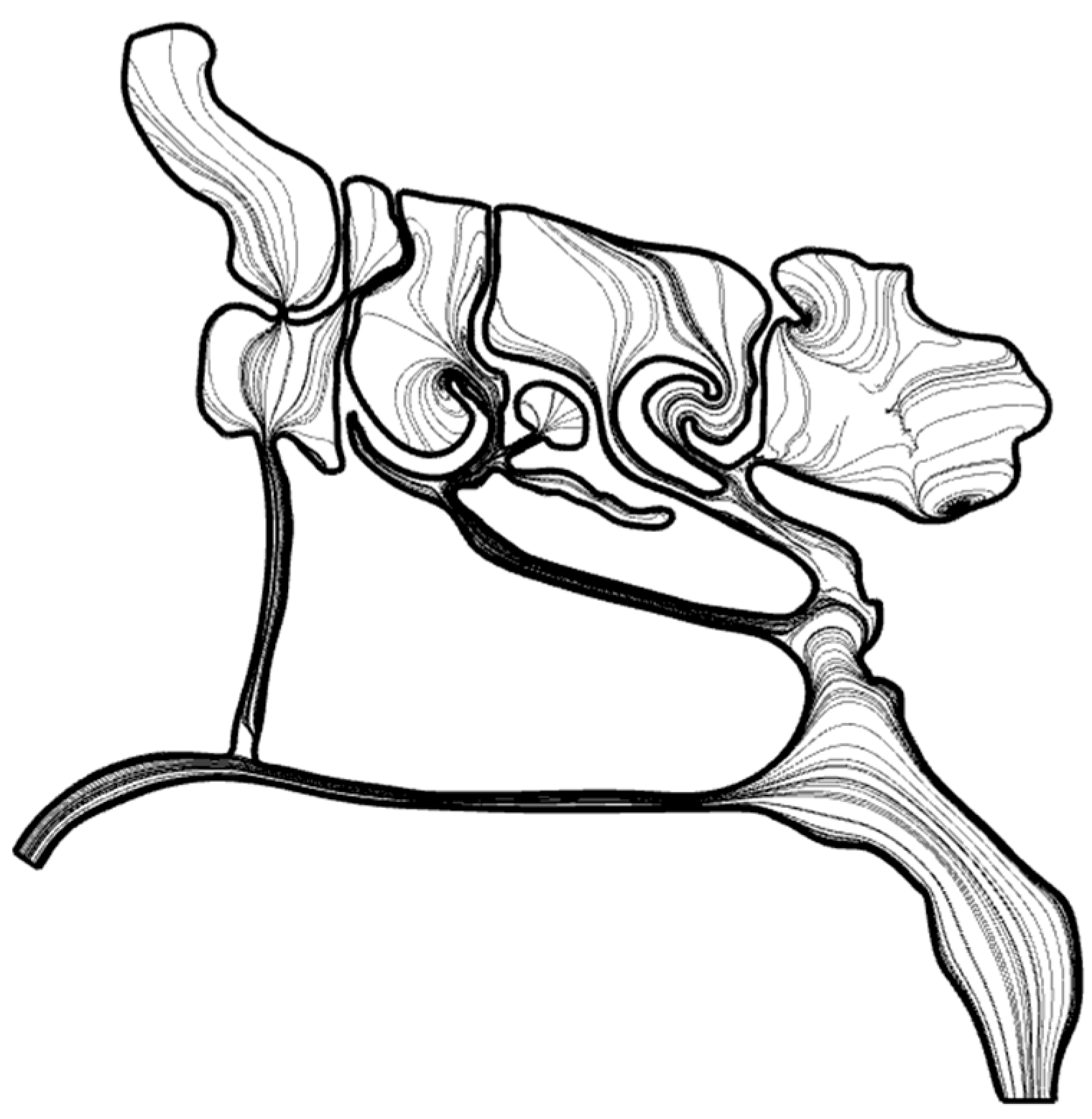

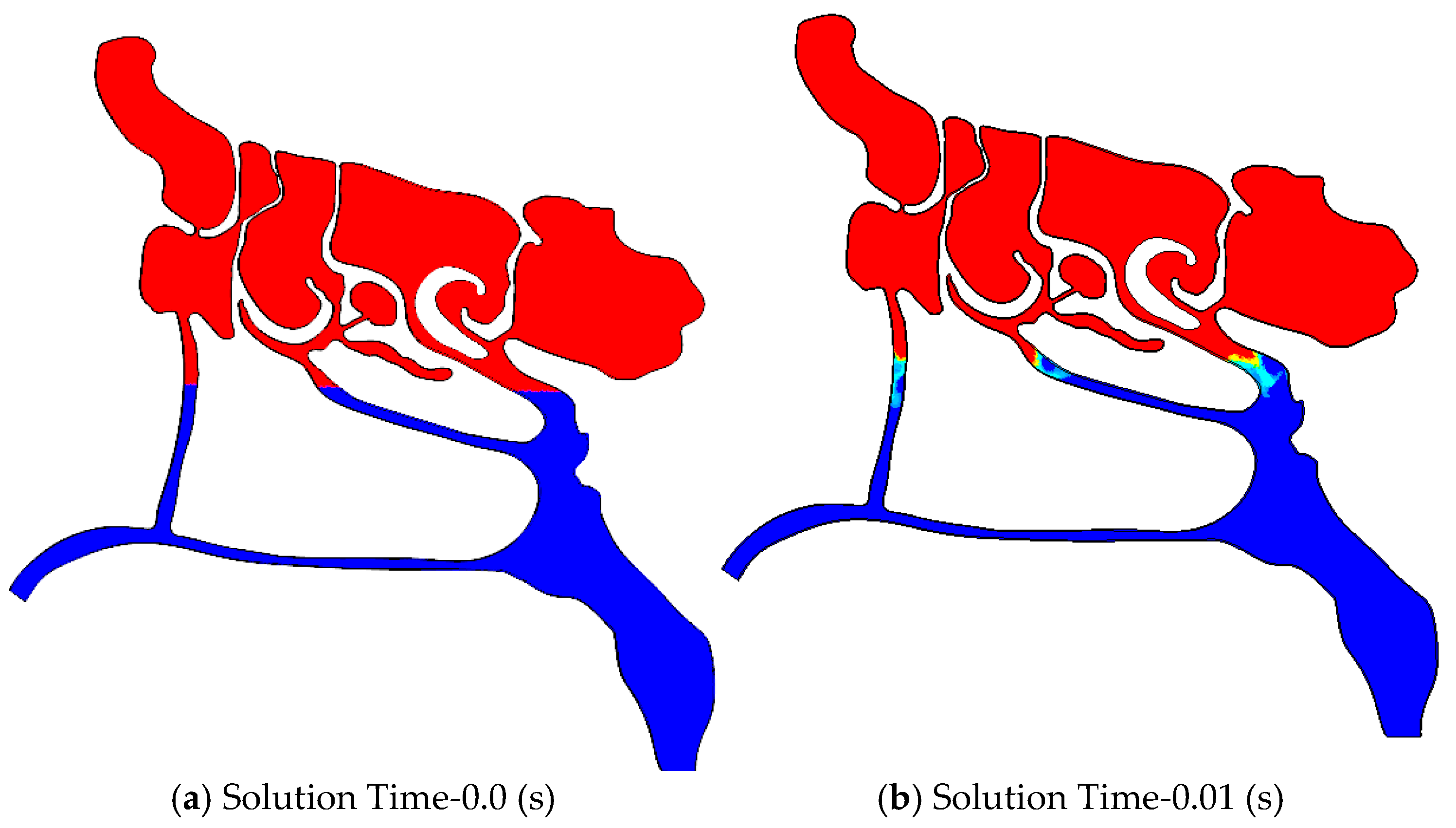

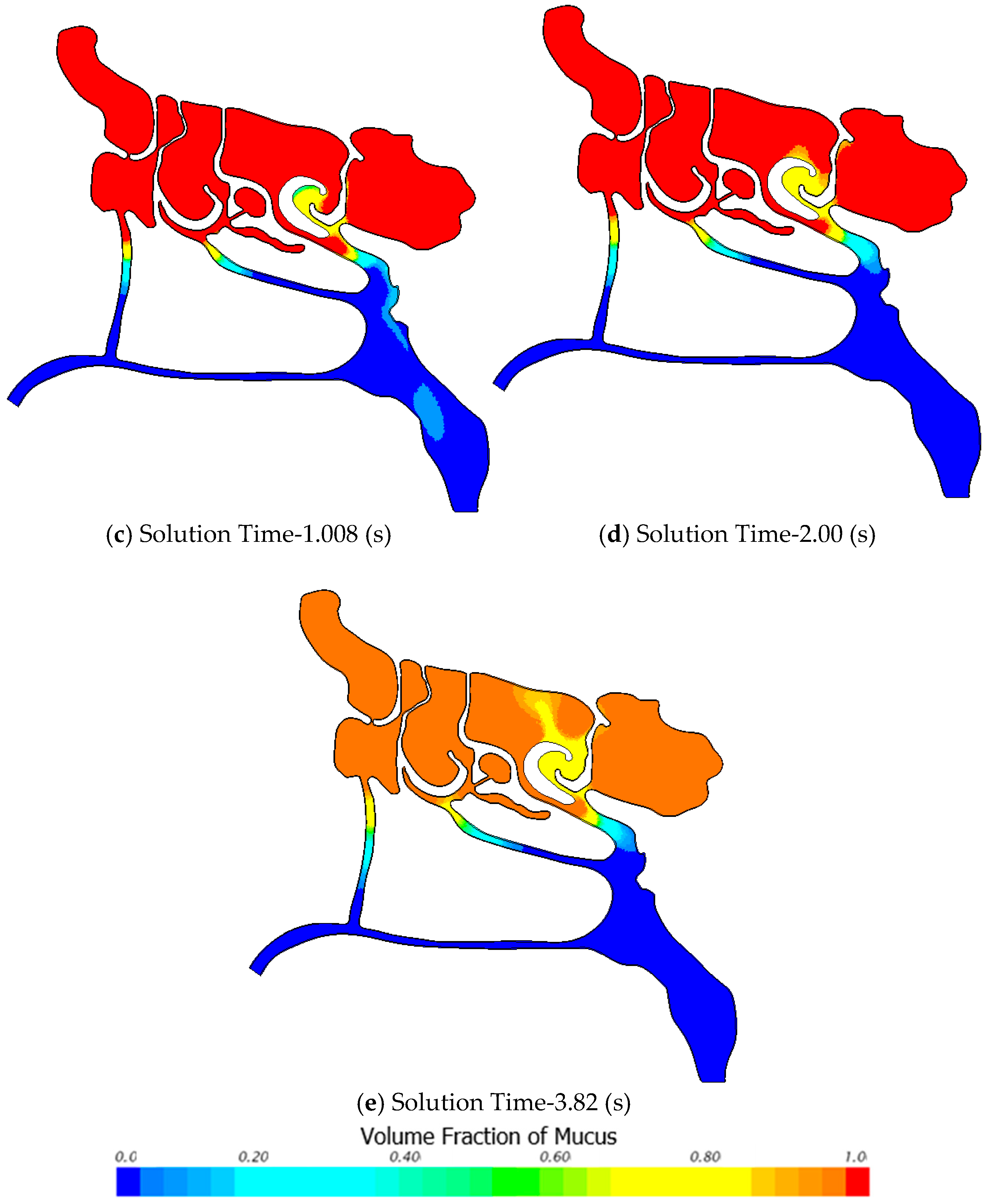

3.2.3. Air-Mucus Two-Phase Flow Simulation

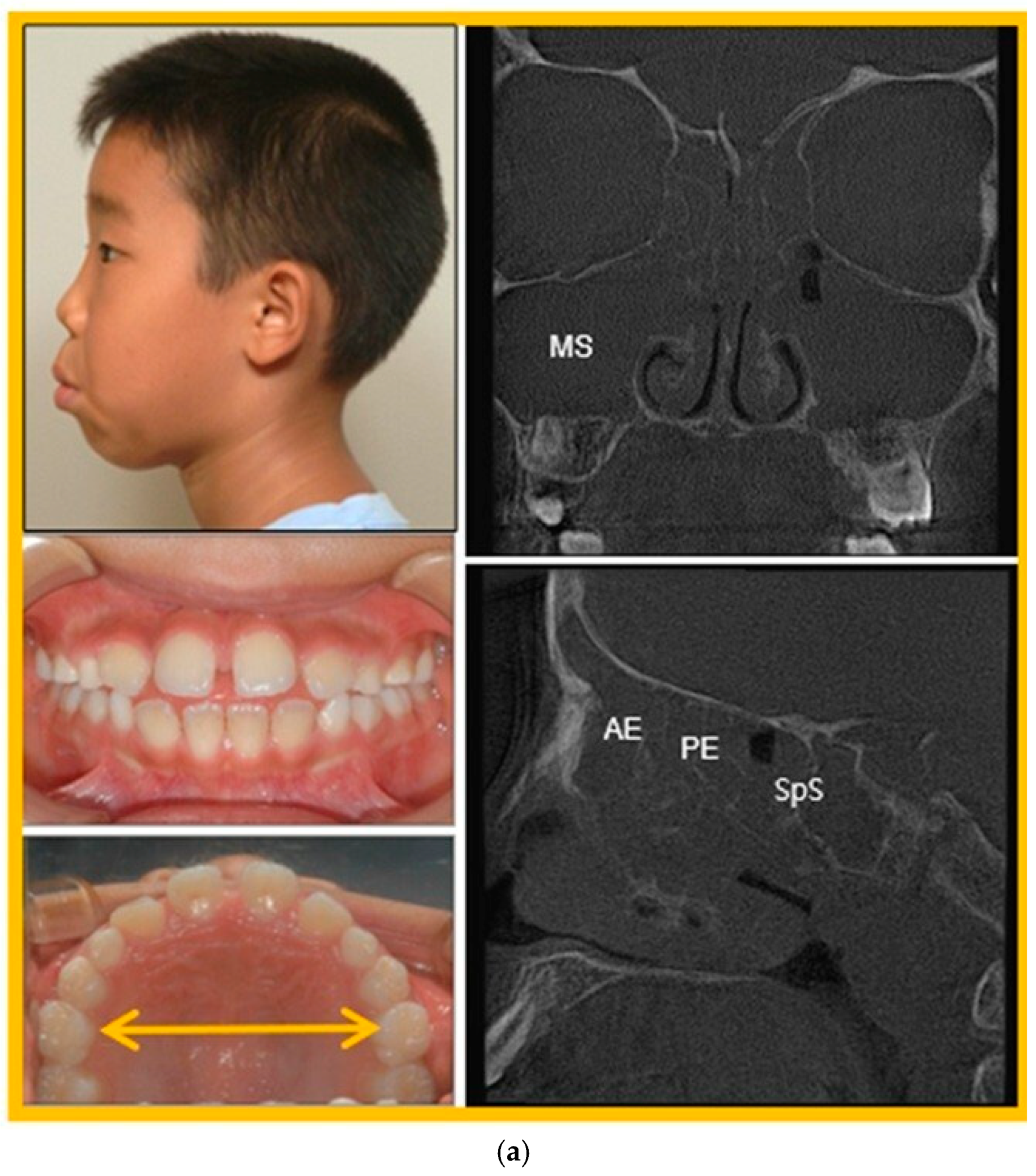

3.3. Patient Case Report

4. Limitations of This Research

5. Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Derichsweiler, H. Die Gaumennahtsprengung. Fortschr. Kieferorthop. 1953, 14, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, H. The apical base after rapid spreading of the maxillary bones. Trans. Eur. Orthod. Soc. 1956, 32, 266–278. [Google Scholar]

- Mew, J.R. Semi-rapid maxillary expansion. Br. Dent. J. 1977, 143, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseri, H.; Ozsoy, S. Semirapid maxillary expansion—A study of long-term transverse effects in older adolescents and adults. Angle Orthod. 2004, 74, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, T.; Saitoh, I.; Takemoto, Y.; Inada, E.; Kanomi, R.; Hayasaki, H.; Yamasaki, Y. Improvement of nasal airway ventilation after rapid maxillary expansion evaluated with computational fluid dynamics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2012, 141, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Koenig, L.J.; Pruszynski, J.E.; Bradley, T.G.; Bosio, J.A.; Liu, D. Dimensional changes of upper airway after rapid maxillary expansion: A prospective cone-beam computed tomography study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Filho, V.A.; Monnazzi, M.S.; Gabrielli, M.A.; Spin-Neto, R.; Watanabe, E.R.; Gimenez, C.M.; Santos-Pinto, A.; Gabrielli, M.F. Volumetric upper airway assessment in patients with transverse maxillary deficiency after surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Mathur, R. Maxillary expansion. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2010, 3, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Choi, J.; Kim, H.; Yi, S.; Yang, Y.; Mitani, Y. Protraction effect of RAMPA on maxillae, upper airway and hyoid bone position; finite element analysis. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2018, 2, 2423–2428. [Google Scholar]

- Mitani, Y.; Choi, B.; Choi, J. Anterosuperior protraction of maxillae using the extra-oral device, RAMPA; finite element method. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 21, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshfeghi, M.; Mitani, Y.; Choi, B.; Emamy, P. Finite element simulations of the effects of an extra-oral device, RAMPA, on anterosuperior protraction of the maxilla and comparison with gHu-1 intraoral device. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitani, Y.; Moshfeghi, M.; Kumamoto, N.; Choi, B. Finite element and clinical analyses of effects of a new intraoral device (VomPress) combined with extra-oral RAMPA on improving the overjet of craniofacial complex. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 25, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshfeghi, M.; Mitani, Y.; Okai-Kojima, Y.; Choi, B.; Emamy, P. RAMPA therapy: Impact of suture stiffness on the anterosuperior protraction of maxillae; finite element analysis. Oral 2025, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jory, M.; Donnarumma, D.; Blanc, C.; Bellouma, K.; Fort, A.; Vachier, I.; Massiera, G. Mucus from human bronchial epithelial cultures: Rheology and adhesion across length scales. Interface Focus 2022, 12, 20220028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauwald, S.M.; Michel, J.; Brandt, M.; Vielsmeier, V.; Stemmer, C.; Krenkel, L. Experimental studies and mathematical modelling of the viscoelastic rheology of tracheobronchial mucus from respiratory-healthy patients. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2023, 18, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R.R.; Banerjee, A. Effect of non-Newtonian dynamics on the clearance of mucus from bifurcating lung airway models. J. Biomech. Eng. 2021, 143, 021011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Seto, R.; Zhang, H.; Che, B.; Liu, L.; Deng, L. Highly distinctive linear and nonlinear rheological behaviours of mucin-based protein solutions as simulated normal and asthmatic human airway mucus. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 043108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.T.; Wain, R.A.J.; Dari, S.; Whitty, J.P.; Smith, D.J. Non-identifiability of parameters for a class of shear-thinning rheological models, with implications for haematological fluid dynamics. J. Biomech. 2019, 85, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tretiakow, D.; Witkowska, E.; Skorek, A. Maxillary sinus aeration analysis using computational fluid dynamics. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfield-McAlpine, P.; Fletcher, D.F.; Zhang, F.; Inthavong, K. Increasing Airflow Ventilation in a nasal maxillary ostium using optimised shape and pulsating flows. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2025, 24, 1343–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modaresi, M.A. Numerical investigation of mucociliary clearance using power law and thixotropic mucus layers under discrete and continuous cilia motion. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2023, 22, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Influence of intranasal drugs on human nasal mucociliary clearance and ciliary beat frequency. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2019, 11, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.H.; Lee, H.P.; Lim, K.M.; Wang, D.Y. Effect of accessory ostia on maxillary sinus ventilation: A computational fluid dynamics analysis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 76, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, N.; Wilson, A.N.; Jones, M.; Middleton, J.; Robertson, N.R. Stresses induced by edgewise appliances in the periodontal ligament—A finite element study. Angle Orthod. 1992, 62, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rees, J.S.; Jacobsen, P.H. Elastic modulus of the periodontal ligament. Biomaterials 1997, 18, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.K.; Bayome, M.; Ahn, C.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, K.B.; Mo, S.S.; Kook, Y.-A. Stress distribution and displacement by different bone-borne palatal expanders with micro-implants: A three-dimensional finite-element analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2014, 36, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.C.; Park, J.H.; Bayome, M.; Kim, K.B.; Araujo, E.A.; Kook, Y.A. Effect of bone-borne rapid maxillary expanders with and without surgical assistance on the craniofacial structures using finite element analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 145, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaida, L.; Moldovan, L.; Lile, I.E.; Todor, B.I.; Porumb, A.; Tig, I.; Bratu, D.C. A comparative study on mechanical properties of some thermoplastic and thermoset resins used for orthodontic appliances. Mater. Plast. 2015, 52, 364–367. [Google Scholar]

- Miroshnichenko, K.; Liu, L.; Tsukrov, I.; Li, Y. Mechanical model of suture joints with fibrous connective layer. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2018, 111, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.K.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wirtz, D.; Hanes, J. Micro- and macrorheology of mucus. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.; Thompson, M.; Stevens, R.; Heneghan, C.; Plüddemann, A.; Maconochie, I.; Tarassenko, L.; Mant, D. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children: A systematic review. Lancet 2011, 377, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sinus | Drainage Pathway | Approximate Size/Features |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal sinus | Frontal drainage pathway → direct to middle meatus, or via infundibulum to middle meatus → nasal cavity → nasopharynx | ~2–4 mm |

| Ethmoid bulla | Typically drains posteriorly through retrobullar cleft → middle meatus → nasal cavity → nasopharynx | Variable pneumatization (up to several mm); one of the largest ethmoid air cells |

| Maxillary sinus | Infundibulum → middle meatus → nasal cavity → nasopharynx | ~2–4 mm |

| Posterior ethmoid air cells | Superior meatus (and supreme when present) → sphenoethmoid recess → nasal cavity → nasopharynx | Several small ostia (<2 mm each) |

| Sphenoid sinus | Sphenoethmoid recess → nasal cavity → nasopharynx | ~2–5 mm |

| Item | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio (-) |

|---|---|---|

| Cortical bone | 13,800 | 0.26 |

| Cancellous bone | 1370 | 0.3 |

| Periodontal ligament | 50 | 0.49 |

| Teeth | 18,600 | 0.31 |

| Suture (Cartilage) | 10 | 0.49 |

| Acrylic Resin (Orthocryl® DENTAURUM, Ispringen, Germany) | 3543 | 0.3 |

| Stainless steel (AISI 316) | 193,000 | 0.31 |

| Dimensions (mm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.94 | 1.44 | 4.0 | 190 | 105 | 160 | 185 | 35 | 50 |

| Point | With RAMPA (mm) |

|---|---|

| A (near incisive foramen) | 0.151 |

| B | 0.144 |

| C | 0.138 |

| D | 0.128 |

| E (near palatine bone) | 0.101 |

| Air Speed (m/s) | Pressure Drop WRT to Nostril (Pa) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throat | Nostril | Point “P” | Point “Q” | Point “P” | Point “Q” | |

| Case 1 | 1.0 | 1.74 | 2.44 | 0.54 | −26.11 | −149.73 |

| Case 2 | 1.2 | 2.11 | 2.93 | 0.64 | −33.02 | −185.42 |

| Case 3 | 1.5 | 2.62 | 3.67 | 0.78 | −44.21 | −237.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moshfeghi, M.; Mitani, Y.; Okai-Kojima, Y.; Choi, B. Impact of RAMPA Therapy on Nasal Cavity Expansion and Paranasal Drainage: Fluid Mechanics Analysis, CAE Simulation, and a Case Study. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010005

Moshfeghi M, Mitani Y, Okai-Kojima Y, Choi B. Impact of RAMPA Therapy on Nasal Cavity Expansion and Paranasal Drainage: Fluid Mechanics Analysis, CAE Simulation, and a Case Study. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoshfeghi, Mohammad, Yasushi Mitani, Yuko Okai-Kojima, and Bumkyoo Choi. 2026. "Impact of RAMPA Therapy on Nasal Cavity Expansion and Paranasal Drainage: Fluid Mechanics Analysis, CAE Simulation, and a Case Study" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010005

APA StyleMoshfeghi, M., Mitani, Y., Okai-Kojima, Y., & Choi, B. (2026). Impact of RAMPA Therapy on Nasal Cavity Expansion and Paranasal Drainage: Fluid Mechanics Analysis, CAE Simulation, and a Case Study. Biomimetics, 11(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010005