A Comprehensive Review of Computational and Experimental Studies on Skin Mechanics and Meshing: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Optimization Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

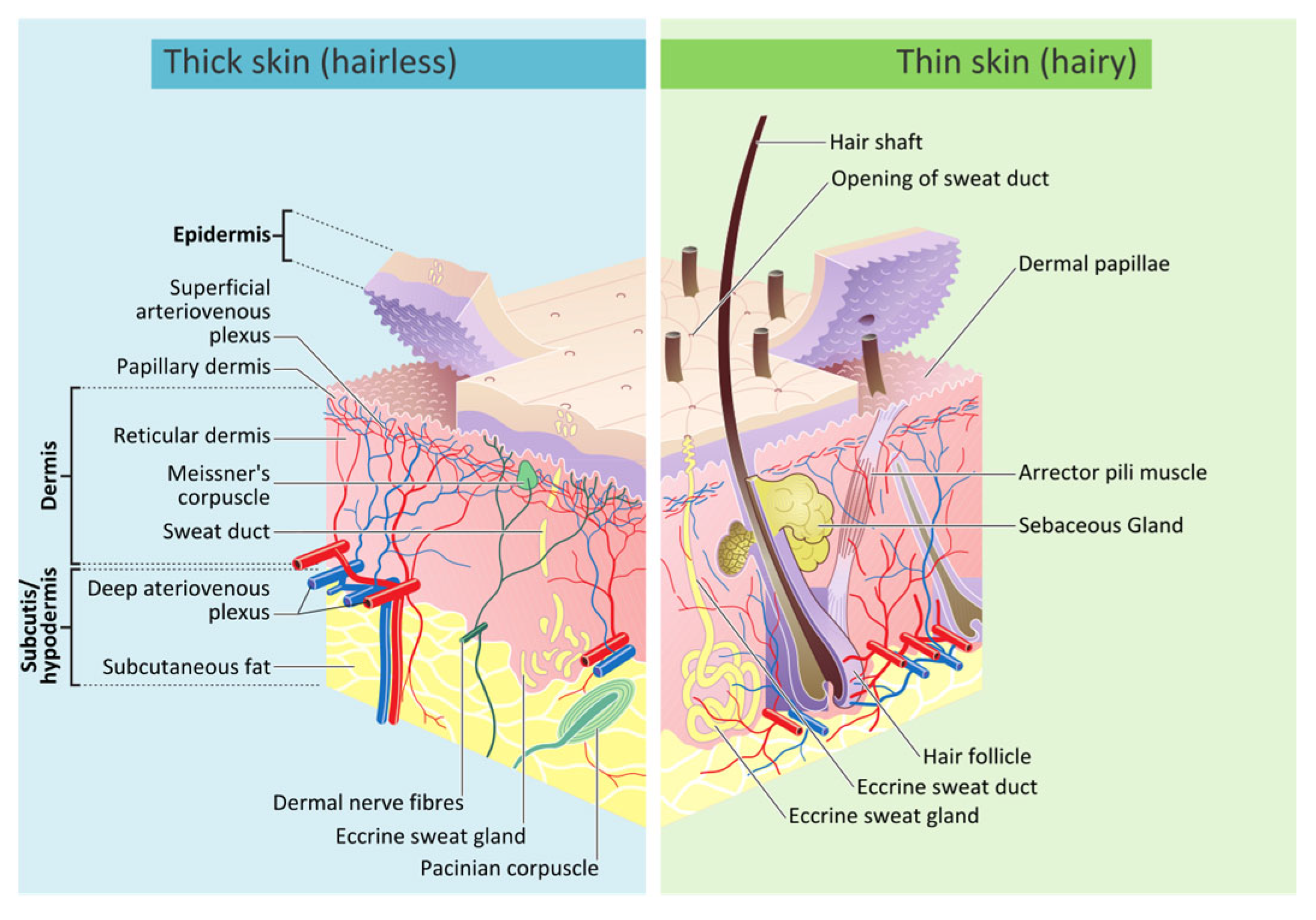

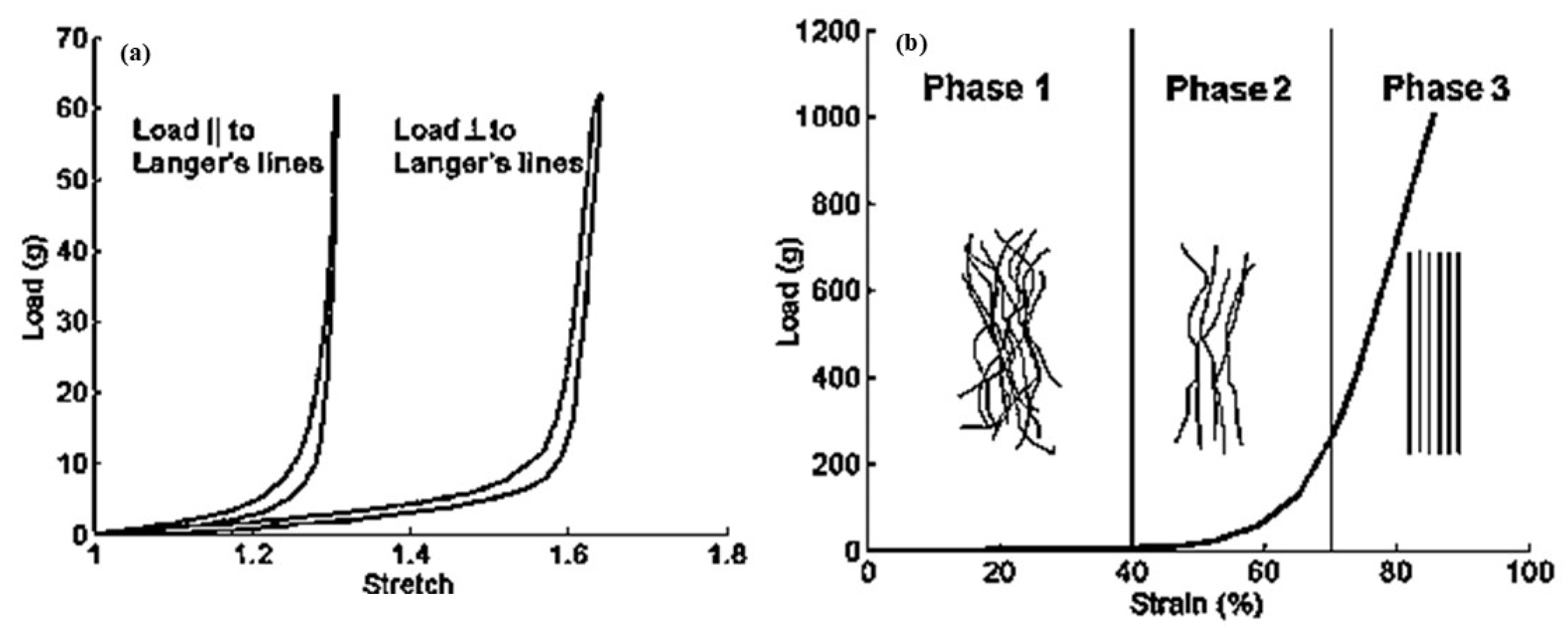

2. Biology of Human Skin

3. Burn Treatment Techniques for Human Skin

3.1. Skin Grafting

| Split-Thickness Skin Graft | Full-Thickness Skin Graft | |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Epidermis + part of the dermis | Epidermis + entire dermis |

| Graft survival | Higher initial graft survival rate due to quicker revascularization | Lower initial graft survival rate due to more complex revascularization |

| Resistance to trauma Cosmetic appearance | Less resistant Poor cosmetic appearance owing to poor color and texture match. Does not prevent contraction. | More resistant Superior cosmetic appearance. It is thicker, preventing wound contraction or distortion. |

| Indications | Temporarily or permanently after removal of skin cancer with a high chance of recurrence. If a flap is not available in areas with limited vascular supply. | When aesthetic outcome is essential (e.g., facial defects). |

| Common uses | Chronic lower-leg ulcers (e.g., venous, irradiated tissues; exposed periosteum, cartilage, or tendon) Surgically induced significant defects (e.g., birthmarks, nevi) | Facial defects: nasal tip, dorsum, ala or side wall, lower eyelid, ear |

| Donor site tissue | Anteromedial thigh, buttock, abdomen, inner or outer aspect of the arm, inner forearm. | Donor sites with a similar color/texture to the defect (e.g., preauricular, postauricular, supraclavicular areas). |

| Disadvantages | Poor cosmetic appearance, higher chance of contraction, limitations in certain burn areas [49]. | Greater risk of graft failure, prolonged healing time for the donor site, potential for hypertrophic scarring, and suitable for more minor burn treatments [48]. |

3.2. Sheet Graft

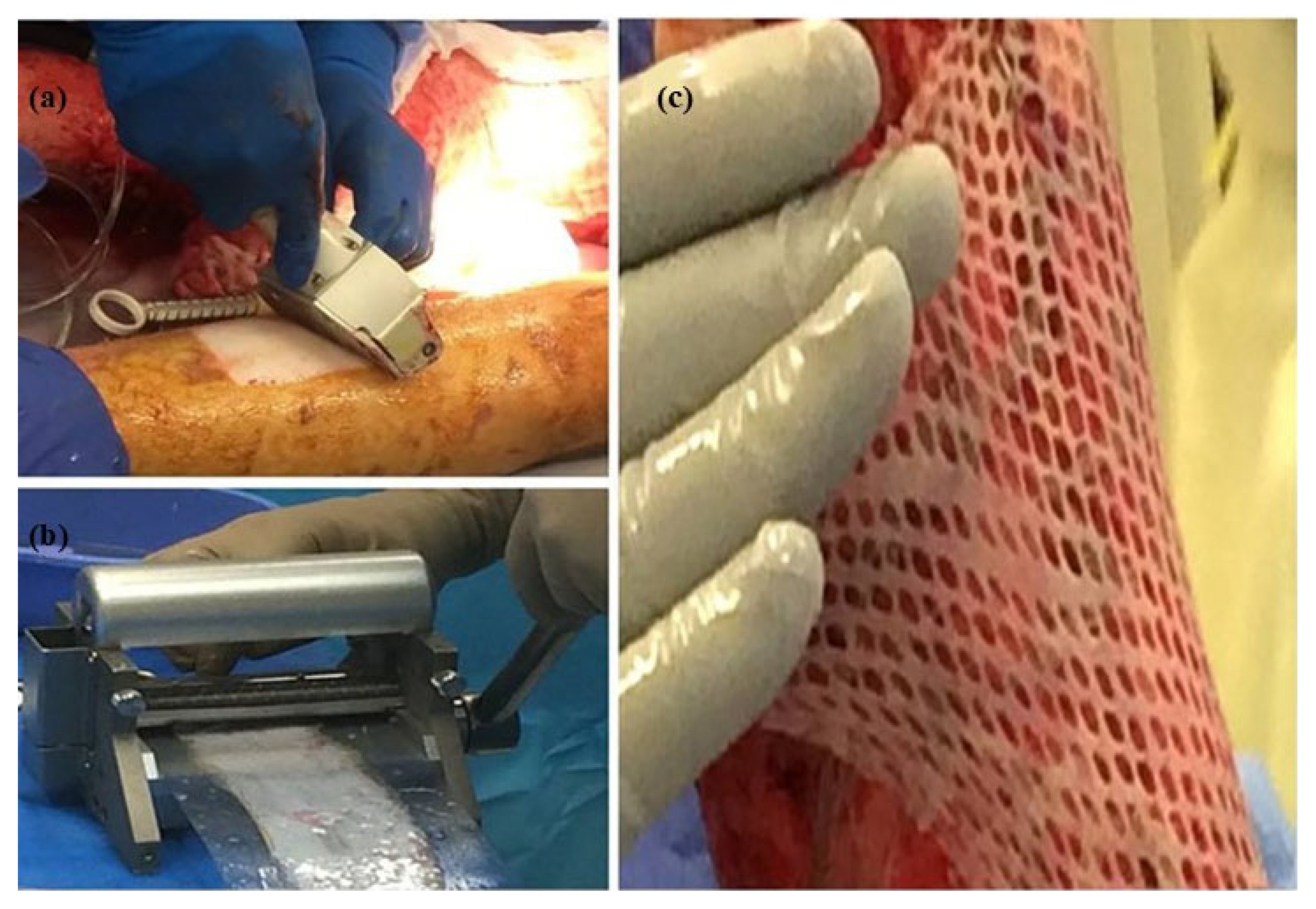

3.3. Skin Meshing

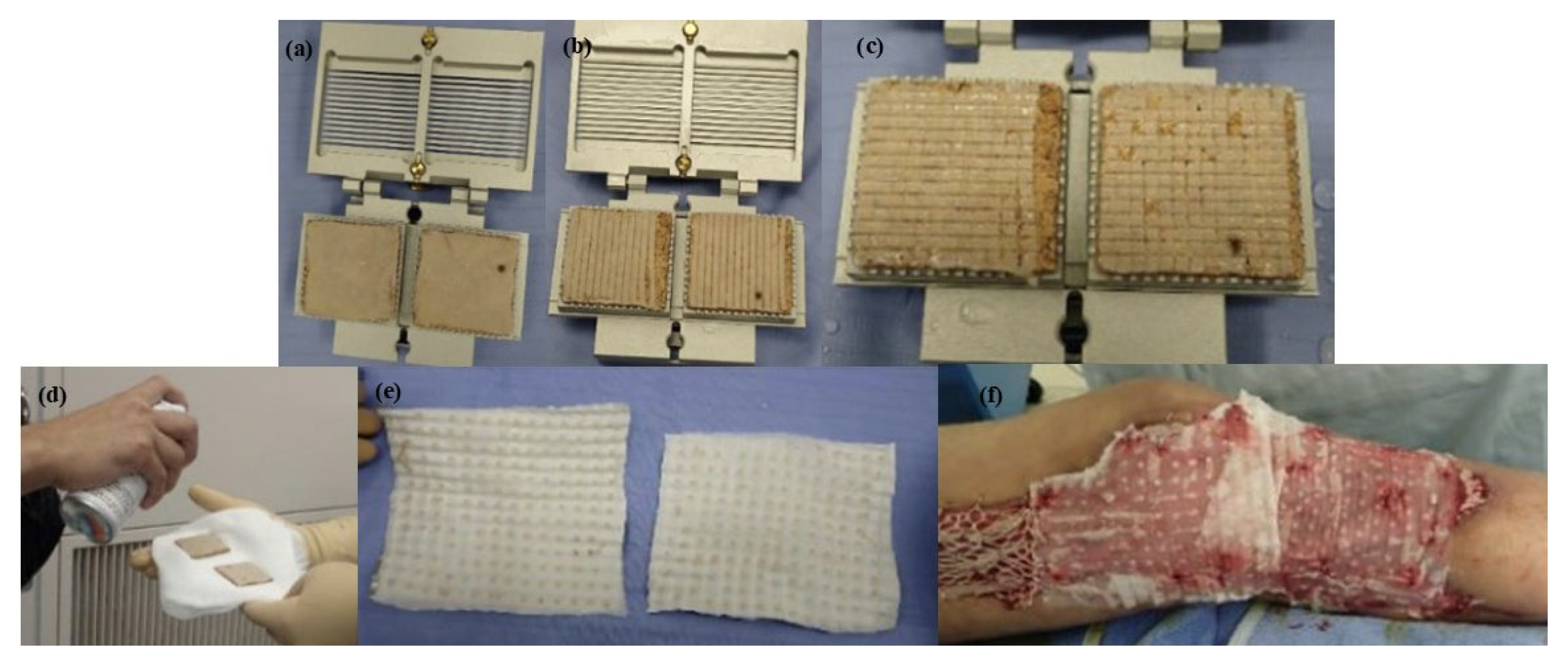

3.4. Meek Technique

4. Experimental and Clinical Studies on Skin Meshing

5. Computational Models of Skin

5.1. Hyperelastic Constitutive Models

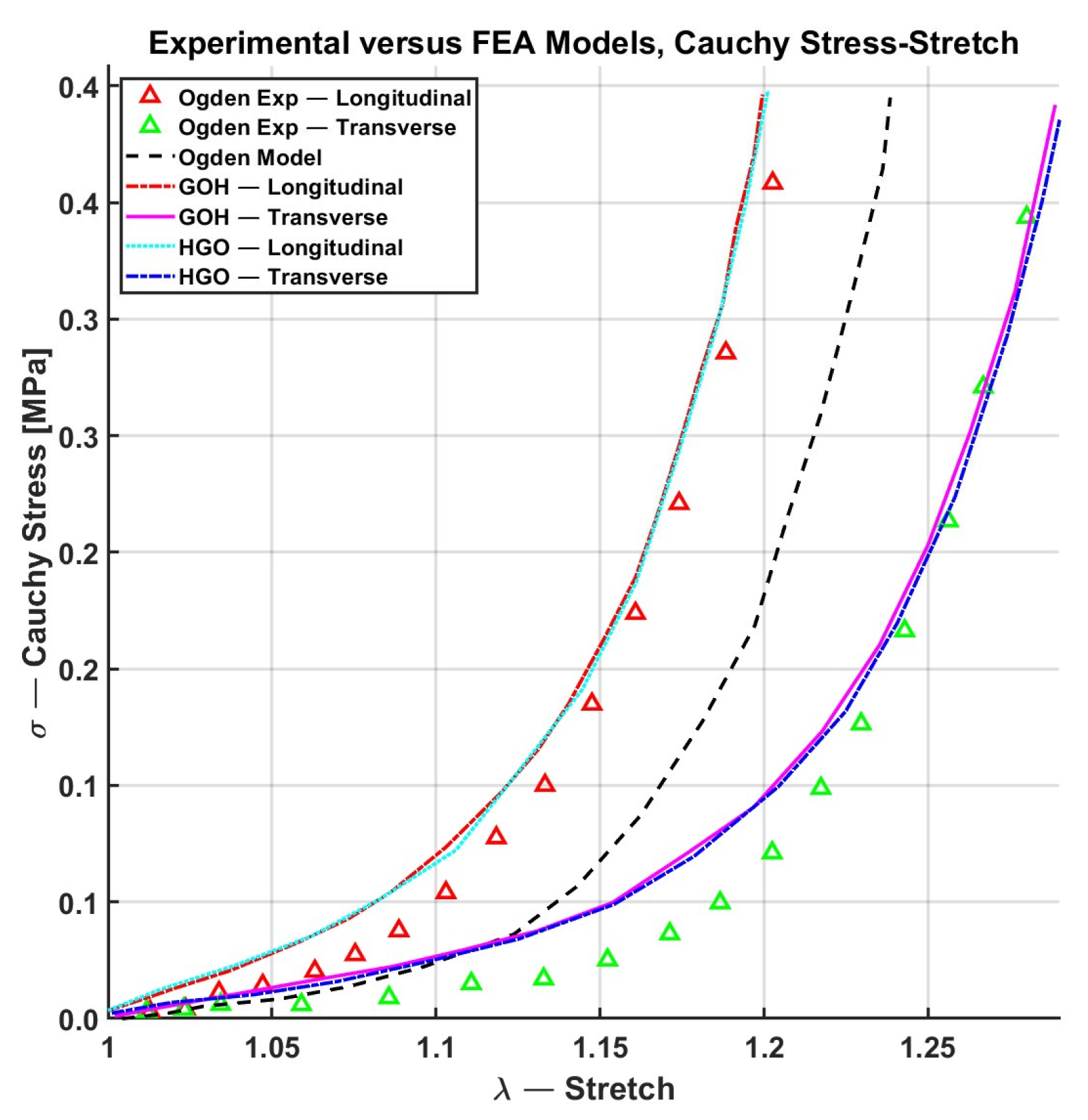

5.1.1. Classical Hyperelastic Models

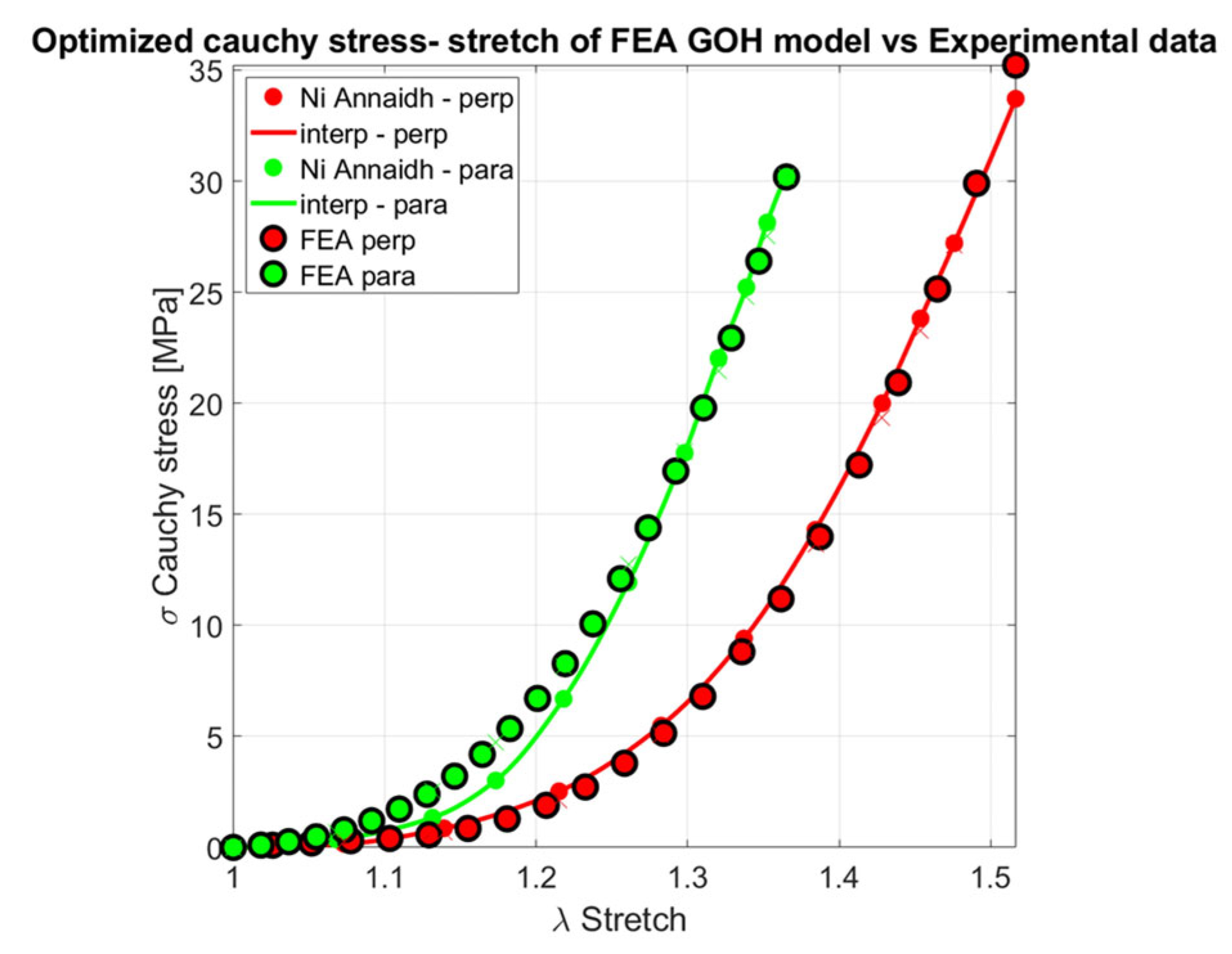

5.1.2. Fiber Distributed-Based Hyperelastic Models

5.1.3. Discrete Fiber-Based Models

5.2. Viscoelastic Constitutive Models

5.2.1. Viscoelastic Probability Density Function Models

5.2.2. Discrete Viscoelastic Constitutive Models

5.3. Quasi-Linear Viscoelastic (QLV) Constitutive Models

5.4. Summary of Constitutive Models and Transition to Damage Mechanics

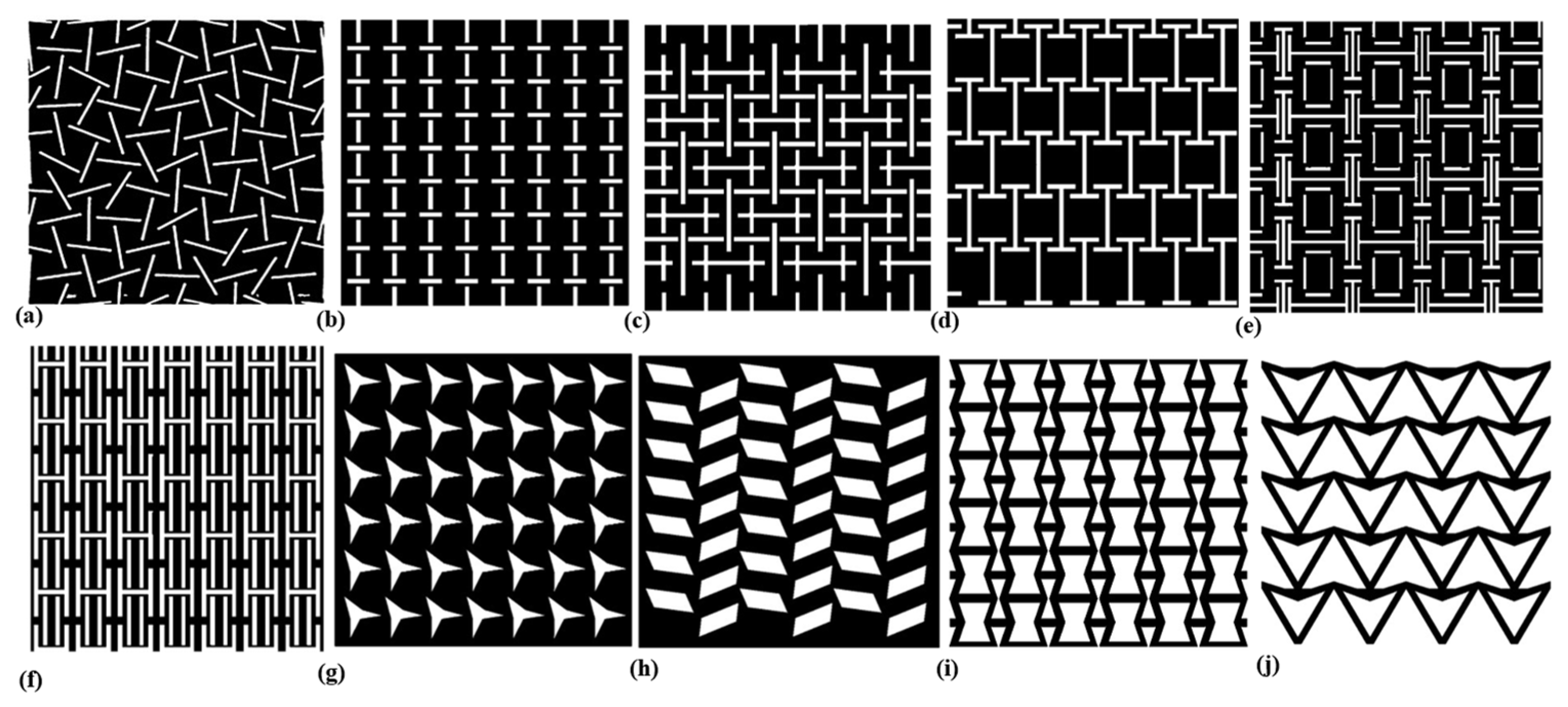

6. Skin Meshing Simulation and Pattern

Auxetic Design for Skin Meshing

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burns. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Peck, M.D. Epidemiology of Burns throughout the World. Part I: Distribution and Risk Factors. Burns 2011, 37, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlhauser, M.; Luze, H.; Nischwitz, S.P.; Kamolz, L.P. Historical Evolution of Skin Grafting—A Journey through Time. Medicina 2021, 57, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyhan, T. Split-Thickness Skin Grafts. In Skin Grafts-Indications, Applications and Current Research; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2011; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh, R.; Gilbert, P.M. Comparison of Commonly Used Mesher Types in Burns Surgery Revisited. Burns 2008, 34, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Nuutila, K.; Collins, K.C.; Huang, A. Evolution of Skin Grafting for Treatment of Burns: Reverdin Pinch Grafting to Tanner Mesh Grafting and Beyond. Burns 2017, 43, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, Z.J.; Kanmounye, U.S.; Naidu, P.; Tapia, M.F.; Bustamante, A.; Bradley, D.; Msokera, C.; Dutton, J.; Magee, W.P.; Gillenwater, J. 59 Burns in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scientometric Analysis of Peer-Reviewed Research. J. Burn Care Res. 2022, 43, S41–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyeh, B.S.; Hayek, S.N.; Gunn, S.W. New Technologies for Burn Wound Closure and Healing—Review of the Literature. Burns 2005, 31, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, E.R. Mesh Skin Grafting. In Current Techniques in Small Animal Surgery; Teton NewMedia: Jackson, WY, USA, 2014; pp. 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, M.; Fournier, J.; Krenek, M.; Paton, W. MESHR: A Modular, Economical Skin Graft Hand Roller. 2018. Available online: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/bioe_senior/77/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Noureldin, M.A.; Said, T.A.; Makeen, K.; Kadry, H.M. Comparative Study between Skin Micrografting (Meek Technique) and Meshed Skin Grafts in Paediatric Burns. Burns 2022, 48, 1632–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Singh, G.; Chanda, A. Development of Hierarchical Auxetic Skin Graft Simulants with High Expansion Potential. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 2023, 5, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.L.; Kagan, R.J. The True Meshing Ratio of Skin Graft Meshers. J. Burn. Care Res. 2014, 35, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, V.; Chanda, A. Biomechanical Modeling of Novel High Expansion Auxetic Skin Grafts. Int. J. Numer. Method. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Singh, G.; Chanda, A. Development and Testing of Skin Grafts Models with Varying Slit Orientations. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 3462–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jor, J.W.Y.; Parker, M.D.; Taberner, A.J.; Nash, M.P.; Nielsen, P.M.F. Computational and Experimental Characterization of Skin Mechanics: Identifying Current Challenges and Future Directions. WIREs Syst. Biol. Med. 2013, 5, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derler, S.; Gerhardt, L.C. Tribology of Skin: Review and Analysis of Experimental Results for the Friction Coefficient of Human Skin. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 45, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaghi Pey Ghaleh, M.; O’Mahoney, D. The Impact of Collagen Fiber and Slit Orientations on Meshing Ratios in Skin Meshing Models. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeput, J.; Nelissen, M.; Tanner, J.C.; Boswick, J. A Review of Skin Meshers. Burns 1995, 21, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, L.; Flynn, C.; Molitor, M.; Chong, S.; Henys, P. Graft Orientation Influences Meshing Ratio. Burns 2018, 44, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Chanda, A. Biomechanics of Skin Grafts: Effect of Pattern Size, Spacing and Orientation. Eng. Res. Express 2022, 4, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Chanda, A. Finite Element Analysis of Hierarchical Metamaterial-Based Patterns for Generating High Expansion in Skin Grafting. Math. Comput. Appl. 2023, 28, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Annaidh, A.; Bruyère, K.; Destrade, M.; Gilchrist, M.D.; Maurini, C.; Otténio, M.; Saccomandi, G. Automated Estimation of Collagen Fibre Dispersion in the Dermis and Its Contribution to the Anisotropic Behaviour of Skin. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 1666–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, T.C.; Ogden, R.W.; Holzapfel, G.A. Hyperelastic Modelling of Arterial Layers with Distributed Collagen Fibre Orientations. J. R. Soc. Interface 2006, 3, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Luo, X.Y. An Invariant-Based Damage Model for Human and Animal Skins. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 3109–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.; Chanda, A. Auxetic Incisions with Alternating Slit Shapes: A Promising Technique for Enhancing Synthetic Skin Grafts Expansion. Mater. Res. Express 2023, 10, 075802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarsick, P.A.J.; Kolarsick, M.A.; Goodwin, C. Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin. J. Dermatol. Nurses Assoc. 2011, 3, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, E. Skin Stem Cells: Rising to the Surface. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 180, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, H.; Alhajj, M.; Fakoya, A.O.; Sharma, S. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Mendivil, M.F.; Page, A.; Bressloff, N.W.; Limbert, G. A Mechanistic Insight into the Mechanical Role of the Stratum Corneum during Stretching and Compression of the Skin. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 49, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, G.L.; Brown, I.A.; Wildnauer, R.H. The Biomechanical Properties of Skin. CRC Crit. Rev. Bioeng. 1973, 1, 453–495. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Hwang, K. Skin Thickness of Korean Adults. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2002, 24, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Noor, S.N.A.; Mahmud, J. A Review on Synthetic Skin: Materials Investigation, Experimentation and Simulation. Adv. Mat. Res. 2014, 915–916, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- File:Skin Layers.Png—Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Skin_layers.png (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Valencia, I.C.; Falabella, A.F.; Eaglstein, W.H. SKIN GRAFTING. Dermatol. Clin. 2000, 18, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, F.M. Mechanical Behaviour of Human Skin In Vivo—A Literature Review; Nat. Lab. Unclassified Report 820; Philips Research Laboratories: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pissarenko, A.; Meyers, M.A. The Materials Science of Skin: Analysis, Characterization, and Modeling. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 110, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanir, Y.; Fung, Y.C. Two-Dimensional Mechanical Properties of Rabbit Skin—II. Experimental Results. J. Biomech. 1974, 7, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Singla, R.; Chanda, A. Development and Characterization of Novel Anisotropic Skin Graft Simulants. Dermato 2023, 3, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, C.H. Biomechanical Properties of Dermis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1982, 79, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Har-Shai, Y.; Bodner, S.R.; Egozy-Golan, D.; Lindenbaum, E.S.; Ben-Izhak, O.; Mitz, V.; Hirshowitz, B. Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of the Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1996, 98, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmichael, S.W. The Tangled Web of Langer’s Lines. Clin. Anat. 2014, 27, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BROWN, I.A. A Scanning Electron Microscope Study of the Effects of Uniaxial Tension on Human Skin. Br. J. Dermatol. 1973, 89, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, V.R.; Yang, W.; Meyers, M.A. The Materials Science of Collagen. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 52, 22–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissarenko, A.; Yang, W.; Quan, H.; Brown, K.A.; Williams, A.; Proud, W.G.; Meyers, M.A. Tensile Behavior and Structural Characterization of Pig Dermis. Acta Biomater. 2019, 86, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Cortés, V. Types of Skin Grafts. In Skin Grafts for Successful Wound Closure; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsner, R.S.; Falanga, V. Techniques of Split-thickness Skin Grafting for Lower Extremity Ulcerations. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1993, 19, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, D.J. Burn Reconstruction: The Problems, the Techniques, and the Applications. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2009, 36, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thourani, V.H.; Ingram, W.L.; Feliciano, D.V. Factors Affecting Success of Split-Thickness Skin Grafts in the Modern Burn Unit. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2003, 54, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, H.; Martinez, R.; Potgieter, D.; Adams, S.; Rogers, A.D. Experience and Outcomes of Micrografting for Major Paediatric Burns. Burns 2017, 43, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyeh, B.; Masellis, A.; Conte, F. Optimizing Burn Treatment in Developing Low- and Middle-Income Countries with Limited Health Care Resources (Part 1). Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2009, 22, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.; Arya, R.; Gillespie, P. Skin Graft Meshing, over-Meshing and Cross-Meshing. Int. J. Surg. 2012, 10, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, R.; Hubens, A. The Mesh Skin Graft—True Expansion Rate. Burns 1988, 14, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

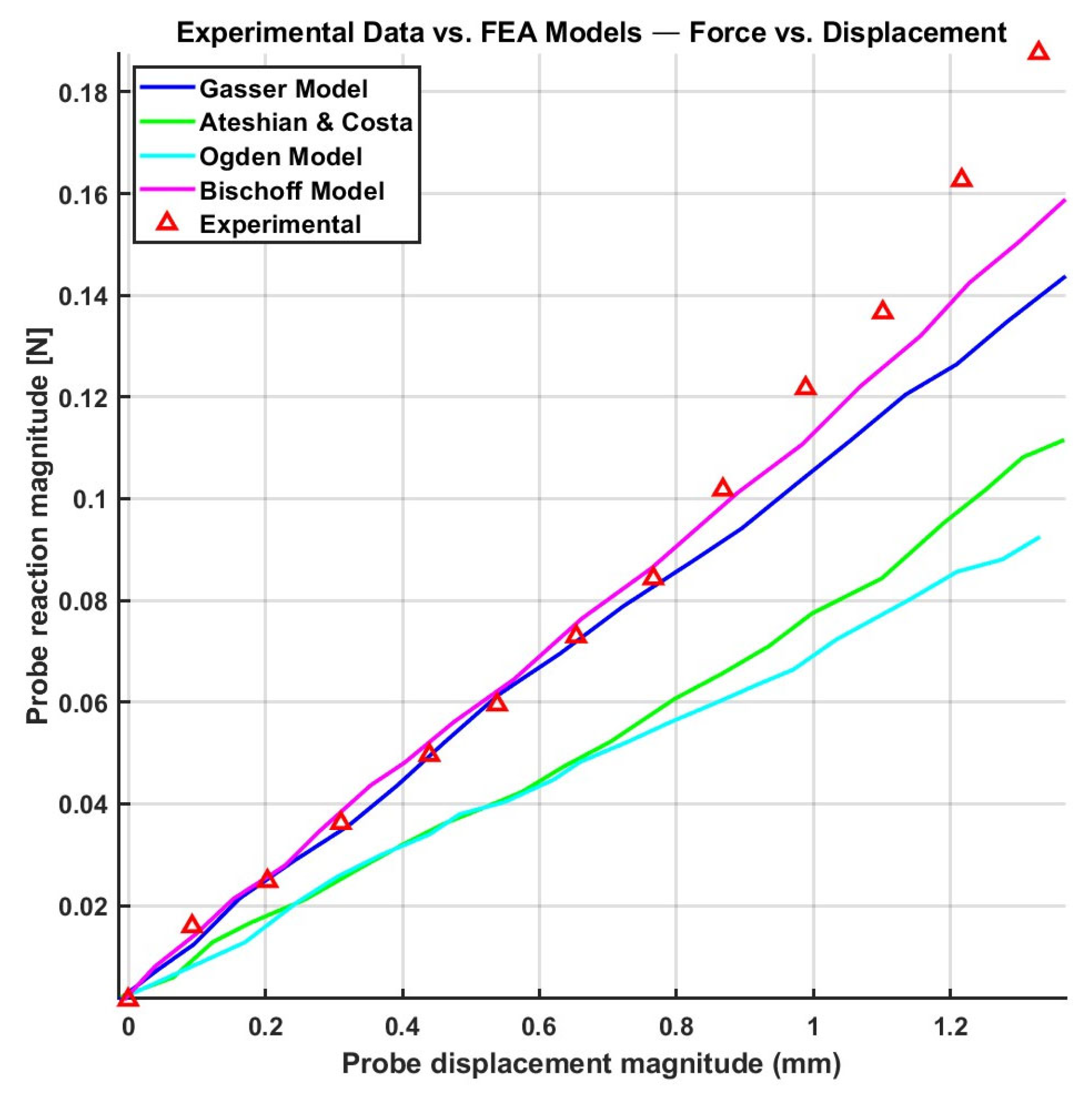

- Flynn, C.; Taberner, A.; Nielsen, P. Measurement of the Force–Displacement Response of in Vivo Human Skin under a Rich Set of Deformations. Med. Eng. Phys. 2011, 33, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Beekman, J.; Hew, J.; Jackson, S.; Issler-Fisher, A.C.; Parungao, R.; Lajevardi, S.S.; Li, Z.; Maitz, P.K.M. Burn Injury: Challenges and Advances in Burn Wound Healing, Infection, Pain and Scarring. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 123, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapking, C.; Panayi, A.; Haug, V.; Palackic, A.; Houschyar, K.S.; Claes, K.E.Y.; Kuepper, S.; Vollbach, F.; Kneser, U.; Hundeshagen, G. Use of the Modified Meek Technique for the Coverage of Extensive Burn Wounds. Burns 2024, 50, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, M.; Hihara, M.; Takeji, K.; Matsuoka, Y.; Okamoto, M.; Fujita, M.; Kakudo, N. Potent Micrografting Using the Meek Technique for Knee Joint Wound Reconstruction. Eplasty 2023, 23, e14. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Nuutila, K.; Kruse, C.; Robson, M.C.; Caterson, E.; Eriksson, E. Challenging the Conventional Therapy: Emerging Skin Graft Techniques for Wound Healing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136, 524e–530e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, D. Skin Grafting. Dermatol. Clin. 1998, 16, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branski, L.K.; Mittermayr, R.; Herndon, D.N.; Norbury, W.B.; Masters, O.E.; Hofmann, M.; Traber, D.L.; Redl, H.; Jeschke, M.G. A Porcine Model of Full-Thickness Burn, Excision and Skin Autografting. Burns 2008, 34, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J.M.; Mansour, J.M.; Davis, B.R. Dynamic Measurement of the Viscoelastic Properties of Skin. J. Biomech. 1991, 24, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.L.; Dodge, M.R.; Kahn, H.; Ballarini, R.; Eppell, S.J. Stress-Strain Experiments on Individual Collagen Fibrils. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 3956–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C. Computational Biophysics of the Skin; Querleux, B., Ed.; Pan Stanford: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Joodaki, H.; Panzer, M.B. Skin Mechanical Properties and Modeling: A Review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 2018, 232, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehsaeid, H.; Arghavani, J.; Naghdabadi, R. A Hyperelastic Constitutive Model for Rubber-like Materials. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2013, 38, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.; Fung, Y.C. The Stress-Strain Relationship for the Skin. J. Biomech. 1976, 9, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateshian, G.A.; Costa, K.D. A Frame-Invariant Formulation of Fung Elasticity. J. Biomech. 2009, 42, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, C.; Glass, P.; Sitti, M.; Di Martino, E.S. Biaxial Mechanical Modeling of the Small Intestine. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2011, 4, 1727–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shergold, O.A.; Fleck, N.A.; Radford, D. The Uniaxial Stress versus Strain Response of Pig Skin and Silicone Rubber at Low and High Strain Rates. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2006, 32, 1384–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Taberner, A.; Nielsen, P. Modeling the Mechanical Response of In Vivo Human Skin Under a Rich Set of Deformations. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 39, 1935–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manschot, J.F.M.; Brakkee, A.J.M. The Measurement and Modelling of the Mechanical Properties of Human Skin in Vivo--II. The Model. J. Biomech. 1986, 19, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanir, Y. The Rheological Behavior of the Skin: Experimental Results and a Structural Model. Biorheology 1979, 16, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Buehler, M.J.; Moran, B. A Constitutive Model of Soft Tissue: From Nanoscale Collagen to Tissue Continuum. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 37, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, G.A.; Gasser, T.C.; Ogden, R.W. A New Constitutive Framework for Arterial Wall Mechanics and a Comparative Study of Material Models. J. Elast. 2000, 61, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, G.A.; Gasser, T.C. A Viscoelastic Model for Fiber-Reinforced Composites at Finite Strains: Continuum Basis, Computational Aspects and Applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2001, 190, 4379–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M Moerman, K. GIBBON: The Geometry and Image-Based Bioengineering Add-On. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transtrum, M.K.; Sethna, J.P. Improvements to the Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm for Nonlinear Least-Squares Minimi-zation. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1201.5885. [Google Scholar]

- Jor, J.W.Y.; Nash, M.P.; Nielsen, P.M.F.; Hunter, P.J. Estimating Material Parameters of a Structurally Based Constitutive Relation for Skin Mechanics. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2011, 10, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanir, Y. Constitutive Equations for Fibrous Connective Tissues. J. Biomech. 1983, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, R.; Douven, L.F.A.; Oomens, C.W.J. Characterisation of Anisotropic and Non-Linear Behaviour of Human Skin In Vivo. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin 1999, 2, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, J.E.; Arruda, E.M.; Grosh, K. Finite Element Modeling of Human Skin Using an Isotropic, Nonlinear Elastic Constitutive Model. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, E.M.; Boyce, M.C. A Three-Dimensional Constitutive Model for the Large Stretch Behavior of Rubber Elastic Materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1993, 41, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, J.E.; Arruda, E.A.; Grosh, K. A Microstructurally Based Orthotropic Hyperelastic Constitutive Law. J. Appl. Mech. 2002, 69, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuyts, F.L.; Vanhuyse, V.J.; Langewouters, G.J.; Decraemer, W.F.; Raman, E.R.; Buyle, S. Elastic Properties of Human Aortas in Relation to Age and Atherosclerosis: A Structural Model. Phys. Med. Biol. 1995, 40, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulliger, M.A.; Fridez, P.; Hayashi, K.; Stergiopulos, N. A Strain Energy Function for Arteries Accounting for Wall Composition and Structure. J. Biomech. 2004, 37, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Rubin, M.B.; Nielsen, P. A Model for the Anisotropic Response of Fibrous Soft Tissues Using Six Discrete Fibre Bundles. Int. J. Numer. Method. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 27, 1793–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Rubin, M.B. An Anisotropic Discrete Fibre Model Based on a Generalised Strain Invariant with Application to Soft Biological Tissues. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2012, 60, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, R.B.; Coulman, S.A.; Birchall, J.C.; Evans, S.L. An Anisotropic, Hyperelastic Model for Skin: Experimental Measurements, Finite Element Modelling and Identification of Parameters for Human and Murine Skin. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 18, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.A.; Maker, B.N.; Govindjee, S. Finite Element Implementation of Incompressible, Transversely Isotropic Hyperelasticity. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1996, 135, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronda, D.R.; Westmann, R.A. Mechanical Characterization of Skin—Finite Deformations. J. Biomech. 1970, 3, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, J.E.; Arruda, E.M.; Grosh, K. A Rheological Network Model for the Continuum Anisotropic and Viscoelastic Behavior of Soft Tissue. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2004, 3, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoemaker, P.A.; Schneider, D.; Lee, M.C.; Fung, Y.C. A Constitutive Model for Two-Dimensional Soft Tissues and Its Application to Experimental Data. J. Biomech. 1986, 19, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassoler, J.M.; Reips, L.; Fancello, E. A Variational Framework for Fiber-reinforced Viscoelastic Soft Tissues. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2012, 89, 1691–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbenel, J.C.; Evans, J.H. The Time-Dependent Mechanical Properties of Skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1977, 69, 318–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, M.B.; Bodner, S.R. A Three-Dimensional Nonlinear Model for Dissipative Response of Soft Tissue. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2002, 39, 5081–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Y. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISSN ISBN 1475722575. [Google Scholar]

- Lokshin, O.; Lanir, Y. Micro and Macro Rheology of Planar Tissues. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3118–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, J.E. Reduced Parameter Formulation for Incorporating Fiber Level Viscoelasticity into Tissue Level Biomechanical Models. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 34, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Taberner, A.J.; Nielsen, P.M.F.; Fels, S. Simulating the Three-Dimensional Deformation of in Vivo Facial Skin. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 28, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldieri, A.; Terzini, M.; Bignardi, C.; Zanetti, E.M.; Audenino, A.L. Implementation and Validation of Constitutive Relations for Human Dermis Mechanical Response. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2018, 56, 2083–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Taberner, A.T.; Fels, S.; Nielsen, P.M.F. Comparison of Anisotropic Models to Simulate the Mechanical Response of Facial Skin. In Lecture Notes in Bioengineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, R.W. Large Deformation Isotropic Elasticity—On the Correlation of Theory and Experiment for Incompressible Rubberlike Solids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1972, 326, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volokh, K.Y. Modeling Failure of Soft Anisotropic Materials with Application to Arteries. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2011, 4, 1582–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volokh, K.Y. Prediction of Arterial Failure Based on a Microstructural Bi-Layer Fiber–Matrix Model with Softening. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grima, J.N.; Mizzi, L.; Azzopardi, K.M.; Gatt, R. Auxetic Perforated Mechanical Metamaterials with Randomly Oriented Cuts. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Singh, G.; Chanda, A. High Expansion Auxetic Skin Graft Simulants for Severe Burn Injury Mitigation. Eur. Burn. J. 2023, 4, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Gupta, V.; Chanda, A. Mechanical Characterization of Rotating Triangle Shaped Auxetic Skin Graft Simulants. Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2022, 23, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Chanda, A. Expansion Potential of Skin Grafts with Alternating Slit Based Auxetic Incisions. Forces Mech. 2022, 7, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Chanda, A. Expansion Potential of Skin Grafts with Novel I-Shaped Auxetic Incisions. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2022, 8, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, X.; Xu, C.; Franklin, D.; Vázquez-Guardado, A.; Bai, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, K.; Monti, G.; et al. Biocompatible Light Guide-Assisted Wearable Devices for Enhanced UV Light Delivery in Deep Skin. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; McCormack, B.A.O. Simulating the Wrinkling and Aging of Skin with a Multi-Layer Finite Element Model. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constitutive Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOH (parallel, Perpendicular) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Razaghi Pey Ghaleh, M.; Marques, D.; O’Mahoney, D. A Comprehensive Review of Computational and Experimental Studies on Skin Mechanics and Meshing: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Optimization Strategies. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010004

Razaghi Pey Ghaleh M, Marques D, O’Mahoney D. A Comprehensive Review of Computational and Experimental Studies on Skin Mechanics and Meshing: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Optimization Strategies. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleRazaghi Pey Ghaleh, Masoumeh, Douglas Marques, and Denis O’Mahoney. 2026. "A Comprehensive Review of Computational and Experimental Studies on Skin Mechanics and Meshing: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Optimization Strategies" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010004

APA StyleRazaghi Pey Ghaleh, M., Marques, D., & O’Mahoney, D. (2026). A Comprehensive Review of Computational and Experimental Studies on Skin Mechanics and Meshing: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Optimization Strategies. Biomimetics, 11(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010004