IHBOFS: A Biomimetics-Inspired Hybrid Breeding Optimization Algorithm for High-Dimensional Feature Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

- An integrated multi-strategy improved hybrid breeding optimization algorithm is proposed, which effectively balances the exploration and exploitation capabilities.

- Ablation experiments are conducted on various types of benchmark functions to verify the effectiveness of the different enhancement strategies incorporated into the improved algorithm.

- The optimal combination of classifier and transfer function is identified based on experimental evaluations of the performance of different options.

- The performance of IHBOFS is evaluated against various metaheuristic-based FS methods on high-dimensional datasets to validate its effectiveness.

2. Related Works

2.1. Hybrid Breeding Optimization Algorithm

2.2. Good Point Set

2.3. Elite Opposition-Based Learning (EOBL)

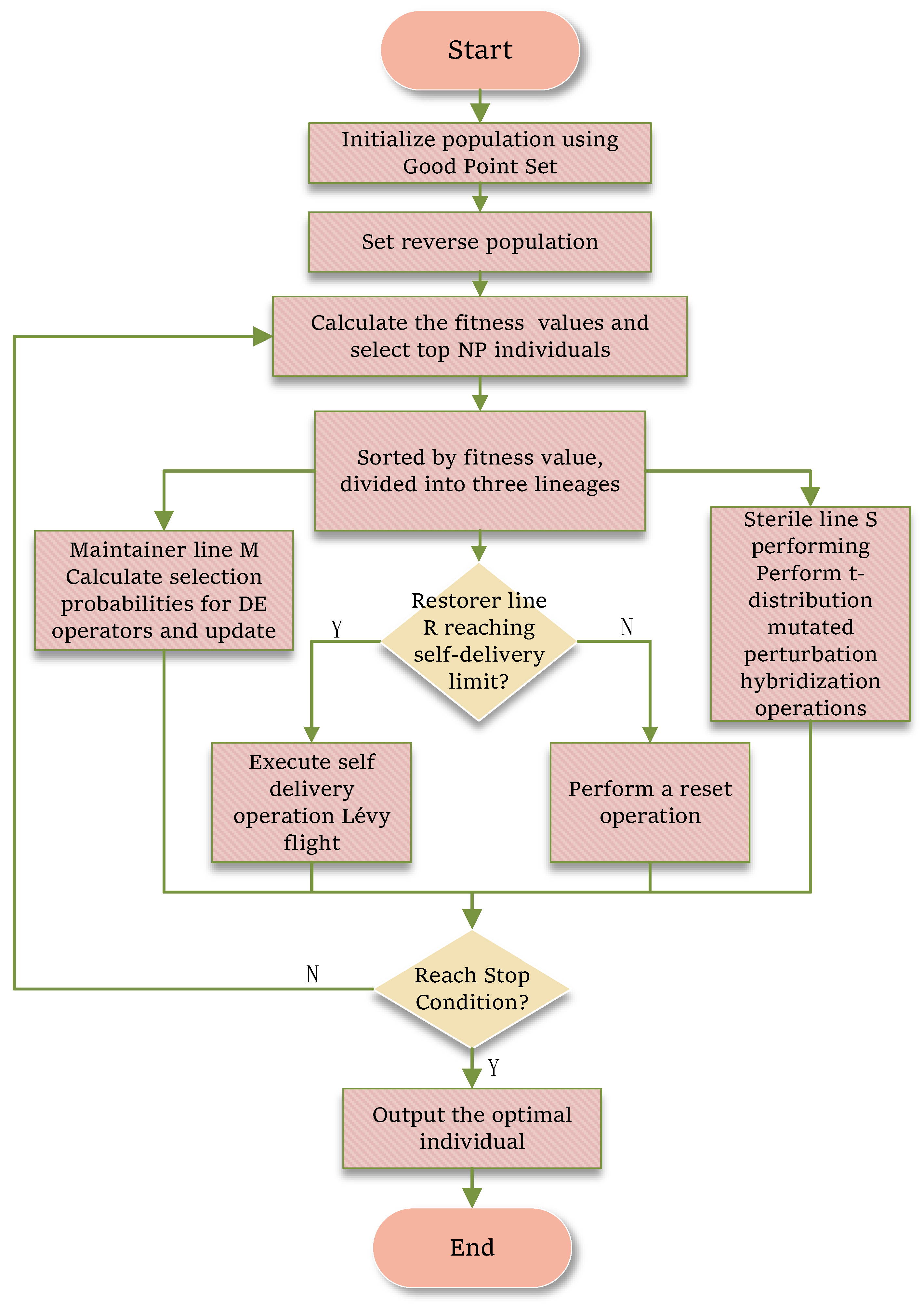

3. The Proposed Method

3.1. Integrated Multi-Strategy Improved HBO

3.1.1. Optimization of Initial Population Generation

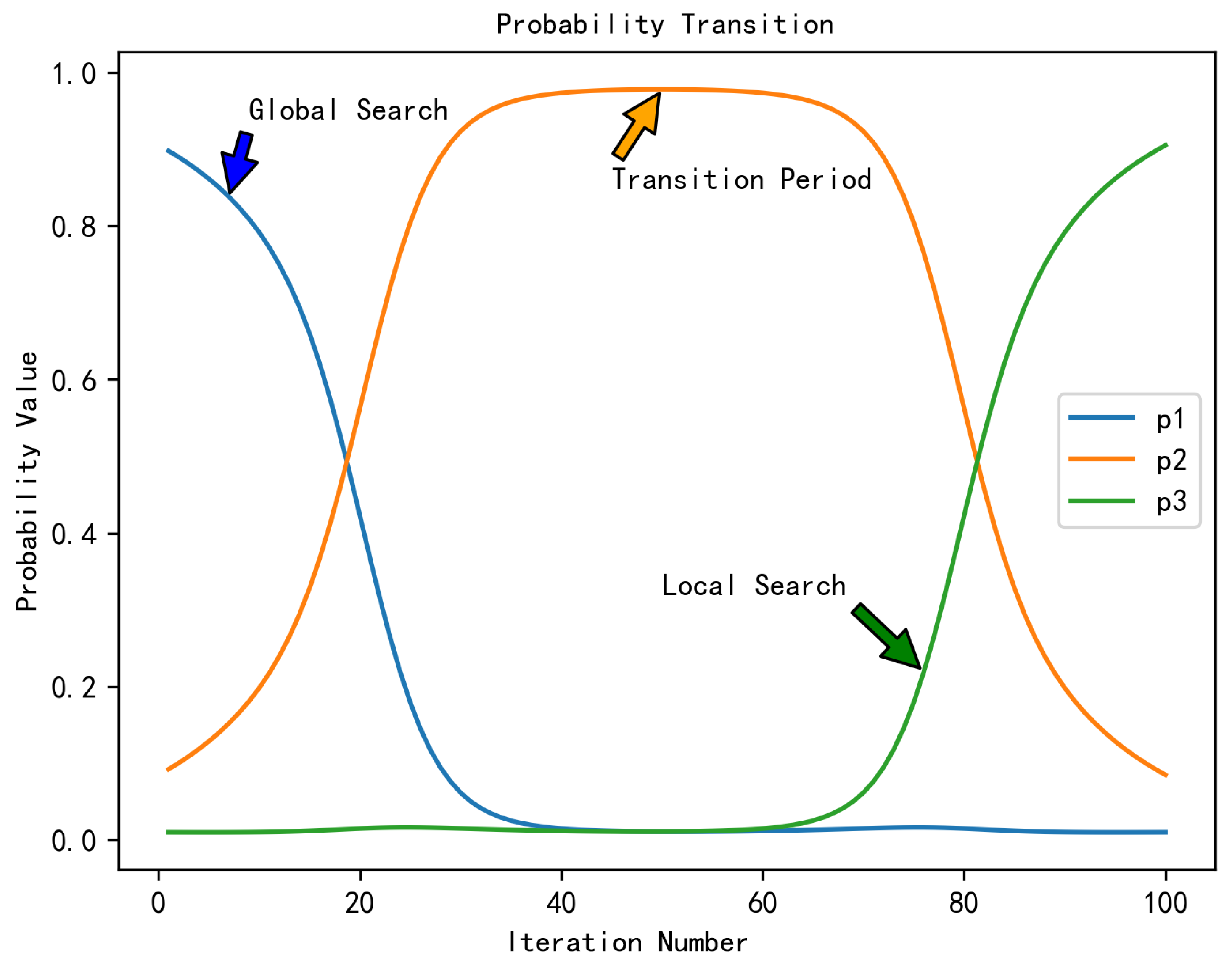

3.1.2. Operations for the Maintainer Line

3.1.3. Operations for the Hybridization Phase

3.1.4. Operations for the Selfing Phase

3.2. IHBOFS Method

3.2.1. Binary Encoding

3.2.2. Fitness Function

3.2.3. Complexity Analysis

4. Experiment Results and Discussion

- Ablation Study: this analysis aims to evaluate the role and significance of each component within the proposed IHBOFS, and experiments are conducted using different combinations of strategies on the CEC2022 test functions.

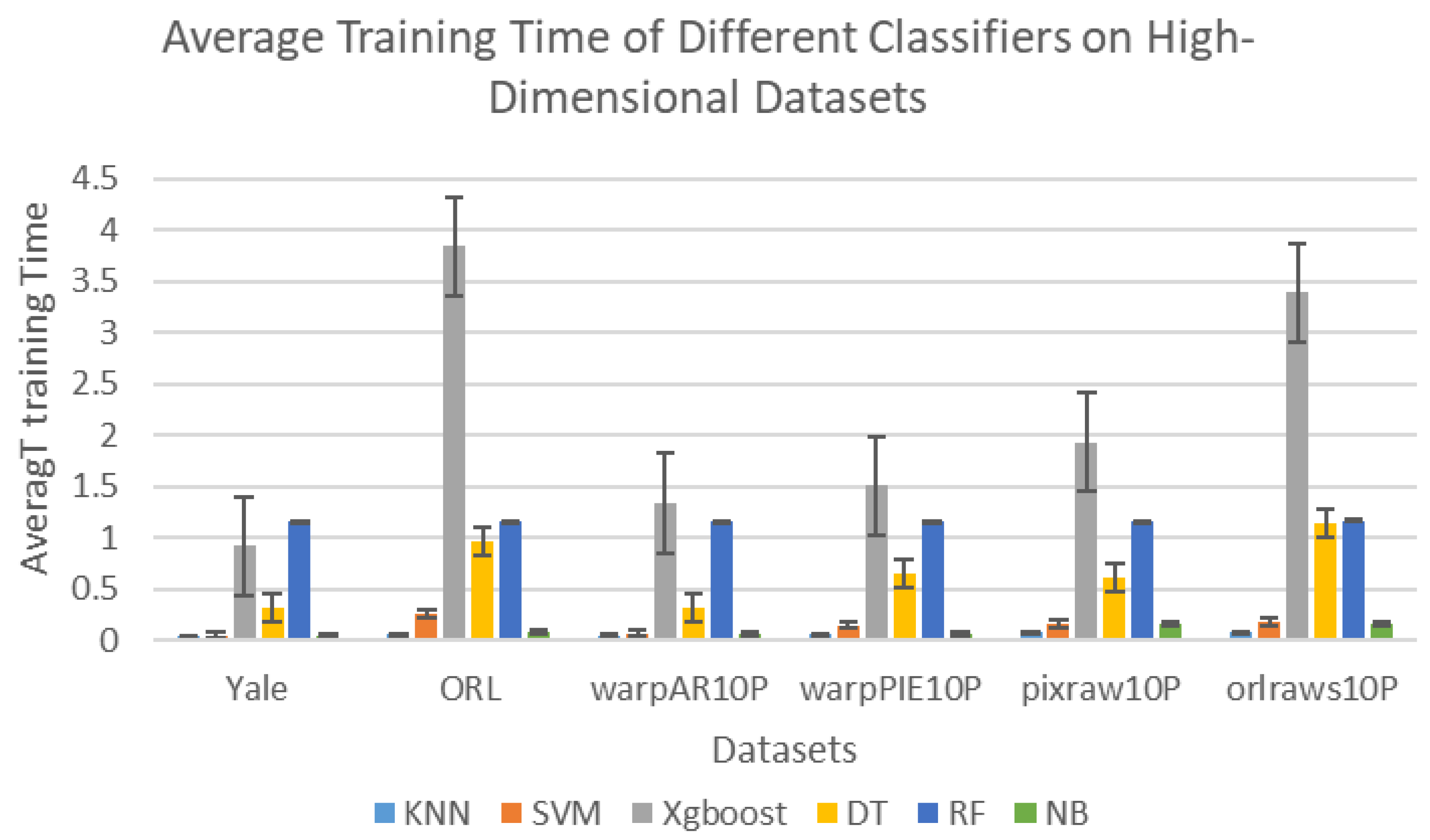

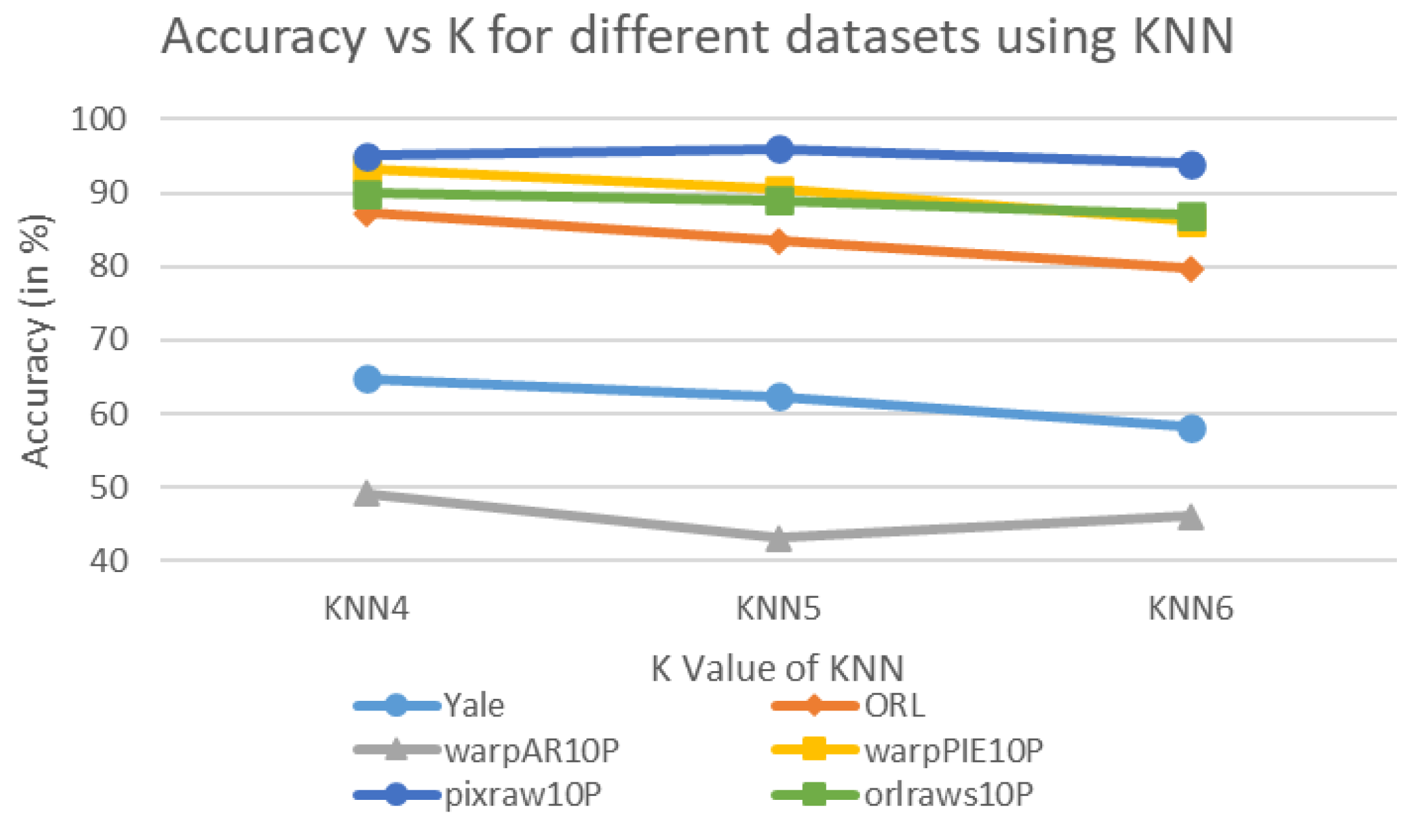

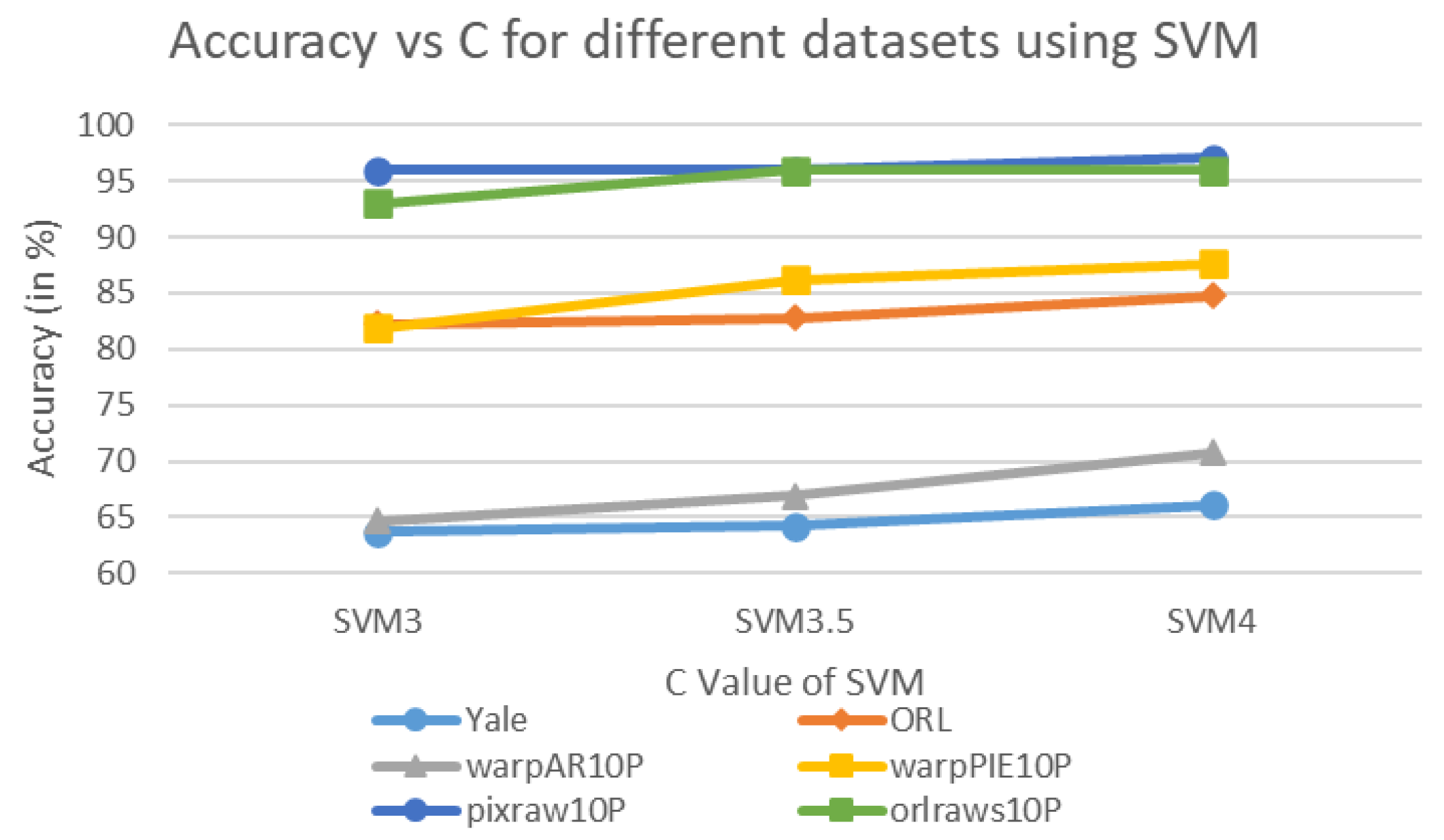

- Classifier and Transfer Function Selection: using high-dimensional real datasets from the Scikit feature selection repository, six classifiers (KNN, SVM, XGBoost, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Naive Bayes) are evaluated and selected based on performance; in addition, both standard HBO and IHBOFS are combined with eight different transfer functions to perform feature selection, in order to identify the best classifier and transfer function.

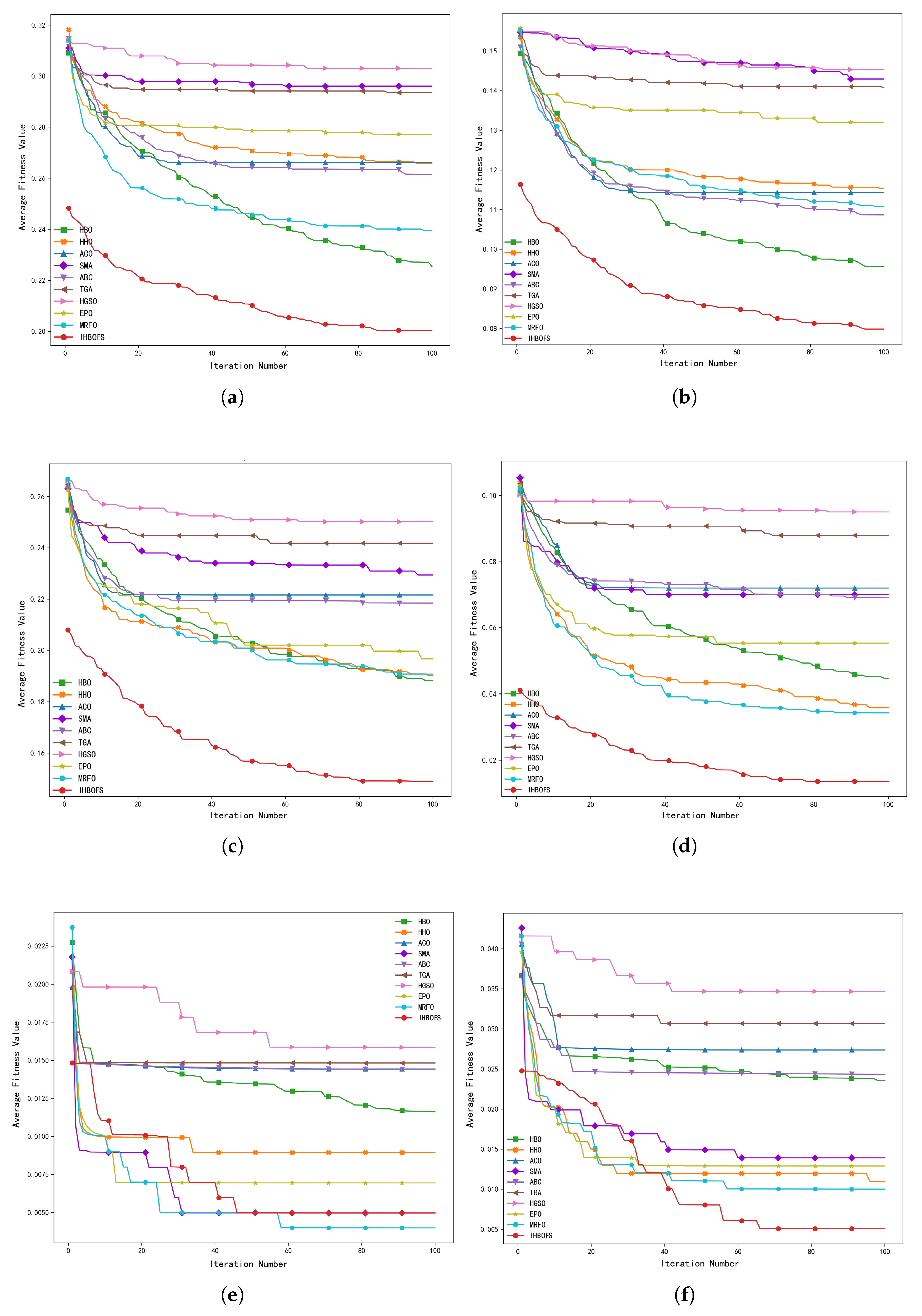

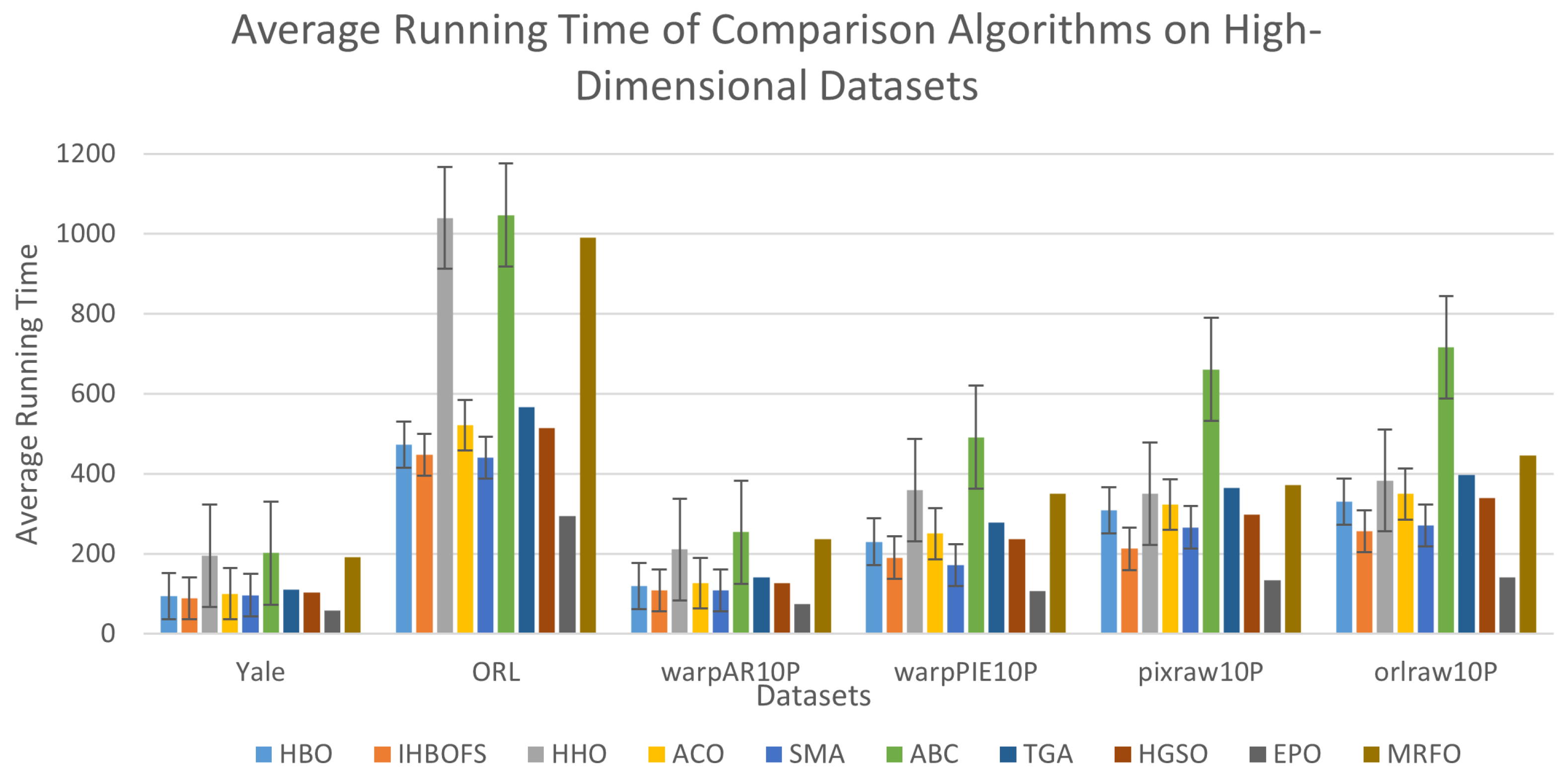

- Comparison with Other Algorithms: based on the selected SVM classifier and the S3 transfer function, IHBOFS is compared with various feature selection algorithms based on metaheuristics across multiple high-dimensional datasets.

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Experimental Settings

4.3. Comparison of Experimental Results and Analysis

4.3.1. Ablation Study

4.3.2. Classifier Performance Evaluation and Selection

4.3.3. Transfer Function Experiments

4.3.4. Comparison with Other Algorithms and Result Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Description of the CEC2022 Benchmark Functions

- Unimodal FunctionsUnimodal functions have only one global optimal solution and no other local optimal solutions in the search space. This category of functions is mainly used to test the convergence speed and accuracy of optimization algorithms, which is a core indicator to measure the basic optimization capability of algorithms.

- Multimodal FunctionsMultimodal functions possess multiple local optimal solutions and one global optimal solution in the search space. They are designed to evaluate the global search capability of optimization algorithms and their ability to avoid falling into local optima. To achieve better performance on multimodal functions, algorithms need to balance exploration and exploitation in the search process, where exploration focuses on discovering new search regions, and exploitation refines the current promising regions.

- Hybrid FunctionsHybrid functions are usually composed of multiple basic test functions, integrating the characteristics of both unimodal and multimodal functions to create more complex and challenging optimization problems. Such functions may contain both easily optimizable regions and difficult-to-optimize regions simultaneously, requiring algorithms to have the ability to switch search strategies adaptively and perform effective searches in different types of search spaces.

- Composition FunctionsComposition functions further extend the concept of hybrid functions by combining multiple hybrid functions or basic functions to construct extremely complex test environments. These functions typically have higher dimensions and more intricate search spaces. The core objective of composite functions is to provide a broader range of challenges to assess the adaptability and robustness of algorithms when facing various types of optimization problems, while also requiring algorithms to have stronger global optimization capabilities and higher computational efficiency to handle the increased complexity.

| Type | ID | Function Name | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unimodal Function | F1 | Shifted and Full Rotated Zakharov Function | 300 |

| Multimodal Functions | F2 | Shifted and Full Rotated Rosenbrock’s Function | 400 |

| F3 | Shifted and Full Rotated Expanded Schaffer’s f6 Function | 600 | |

| F4 | Shifted and Full Rotated Non-Continuous Rastrigin’s Function | 800 | |

| F5 | Shifted and Full Rotated Levy Function | 900 | |

| Hybrid Functions | F6 | Hybrid Function 1 (N = 3) | 1800 |

| F7 | Hybrid Function 2 (N = 6) | 2000 | |

| F8 | Hybrid Function 3 (N = 5) | 2200 | |

| Composition Functions | F9 | Composition Function 1 (N = 3) | 2300 |

| F10 | Composition Function 2 (N = 4) | 2400 | |

| F11 | Composition Function 3 (N = 5) | 2600 | |

| F12 | Composition Function 4 (N = 6) | 2700 |

Appendix B. Transfer Functions in Feature Selection

| S-Shaped Functions | V-Shaped Functions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Function Symbol | Transfer Function | Function Symbol | Transfer Function |

References

- Yang, G.; He, J.; Lan, X.; Li, T.; Fang, W. A fast dual-module hybrid high-dimensional feature selection algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2024, 681, 121185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, N.; Khalil, U.; Ahmad, B.; Alshanbari, H.M.; Hamraz, M.; Ahmad, B.; Khan, D.M. Improved nonparametric survival prediction using CoxPH, Random Survival Forest & DeepHit Neural Network. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Saraf, T.O.Q.; Fuad, N.; Taujuddin, N.S.A.M. Framework of meta-heuristic variable length searching for feature selection in high-dimensional data. Computers 2022, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osama, S.; Shaban, H.; Ali, A.A. Gene reduction and machine learning algorithms for cancer classification based on microarray gene expression data: A comprehensive review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 118946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancer, E.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M. A survey on feature selection approaches for clustering. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 4519–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandvakili, A.; Mansouri, N.; Javidi, M.M. A new feature selection algorithm based on fuzzy-pathfinder optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 17585–17614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaeedi, A.H.; Al-Mahmood, H.H.R.; Alnaseri, Z.F.; Aziz, M.R.; Al-Shammary, D.; Ibaida, A.; Ahmed, K. Fractal feature selection model for enhancing high-dimensional biological problems. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nssibi, M.; Manita, G.; Korbaa, O. Advances in nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization for feature selection problem: A comprehensive survey. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 49, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahawar, K.; Rattan, P. Empowering education: Harnessing ensemble machine learning approach and ACO-DT classifier for early student academic performance prediction. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 4639–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsahaf, A.; Petkov, N.; Shenoy, V.; Azzopardi, G. A framework for feature selection through boosting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 187, 115895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, C.; Ye, X.; Naidoo, R. Harnessing eXplainable artificial intelligence for feature selection in time series energy forecasting: A comparative analysis of Grad-CAM and SHAP. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjei, M.A.; Boostani, R. A hybrid feature selection scheme for high-dimensional data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 113, 104894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vommi, A.M.; Battula, T.K. A hybrid filter-wrapper feature selection using Fuzzy KNN based on Bonferroni mean for medical datasets classification: A COVID-19 case study. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 218, 119612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Rao, C.; Xiao, X.; Hu, F.; Goh, M. Multiple strategies based Grey Wolf Optimizer for feature selection in performance evaluation of open-ended funds. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 86, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Zhai, H. A feature selection based on genetic algorithm for intrusion detection of industrial control systems. Comput. Secur. 2024, 139, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.G. Particle swarm optimization algorithm and its applications: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 2531–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, R.R.; Hussien, A.G.; Gaheen, M.A.; Ewees, A.A.; Hashim, F.A. AEOWOA: Hybridizing whale optimization algorithm with artificial ecosystem-based optimization for optimal feature selection and global optimization. Evol. Syst. 2024, 15, 1753–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Abualigah, L.; Yildiz, A.R.; Hussien, A.G. Modified crayfish optimization algorithm for solving multiple engineering application problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wong, K.C.; Li, X. A self-adaptive weighted differential evolution approach for large-scale feature selection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 235, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, W. A feature weighting particle swarm optimization method to identify biomarker genes. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 December 2022; pp. 830–834. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi, S.K.R.; Saadat, A.; Abaid, Z.; Ni, W.; Li, K.; Guizani, M. Feature selection based on dataset variance optimization using hybrid sine cosine–firehawk algorithm (hscfha). Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 155, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Cui, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. A variable granularity search-based multiobjective feature selection algorithm for high-dimensional data classification. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 27, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, F. Evolutionary multitasking for feature selection in high-dimensional classification via particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 26, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, F. An evolutionary multitasking-based feature selection method for high-dimensional classification. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 52, 7172–7186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancer, E.; Xue, B.; Zhang, M. An evolutionary filter approach to feature selection in classification for both single-and multi-objective scenarios. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 280, 111008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Ma, L.; Chen, H. A hybrid rice optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th International Conference on Computer Science & Education (ICCSE), Nagoya, Japan, 23–25 August 2016; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Z.; Ye, Z.; Zong, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, M. A modified hybrid rice optimization algorithm for solving 0–1 knapsack problem. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 5751–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, M.; Zhang, S.; Ye, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhou, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, L.; Shen, J. A cooperative hybrid breeding swarm intelligence algorithm for feature selection. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 169, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Ma, F.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, W.; Wang, M.; He, Q.; Pan, H.; Shen, J. Dynamic niche technology based hybrid breeding optimization algorithm for multimodal feature selection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Luo, J.; Zhou, W.; Wang, M.; He, Q. An ensemble framework with improved hybrid breeding optimization-based feature selection for intrusion detection. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 151, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; He, C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Gong, D. Evolutionary computation for feature selection in classification: A comprehensive survey of solutions, applications and challenges. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 90, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, T.; Cheng, J.; Lei, Z.; Gao, S. Information gain ratio-based subfeature grouping empowers particle swarm optimization for feature selection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 286, 111380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, E.A.K.; Ahmad, A.; Mohamed, A. Adaptive threshold optimisation for online feature selection using dynamic particle swarm optimisation in determining feature relevancy and redundancy. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 156, 111477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Jing, C. Research on Stochastic Feature Selection Optimization Algorithm Fusing Symmetric Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), Jinan, China, 23–26 August 2024; pp. 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.S.; Al-Sahaf, H.; Mansoori, M.; Welch, I. Behavior-based ransomware classification: A particle swarm optimization wrapper-based approach for feature selection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 121, 108744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, T.; Santhakumar, D.; Balajee, A.; Shreenidhi, H.; Kumar, V.V.; Annand, J.R. Hybrid ant lion mutated ant colony optimizer technique with particle swarm optimization for leukemia prediction using microarray gene data. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 10910–10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Mei, F.; Sun, G.; Zhang, J. Enhancing IoT (Internet of Things) feature selection: A two-stage approach via an improved whale optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 256, 124936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Song, H.M.; Wang, J.S.; Song, Y.W.; Qi, Y.L.; Ma, X.R. GOG-MBSHO: Multi-strategy fusion binary sea-horse optimizer with Gaussian transfer function for feature selection of cancer gene expression data. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Abdalkarim, N.; Samee, N.A.; Alabdulhafith, M.; Mohamed, E. Improved Kepler Optimization Algorithm for enhanced feature selection in liver disease classification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 297, 111960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Arora, B. HFCCW: A novel hybrid filter-clustering-coevolutionary wrapper feature selection approach for network anomaly detection. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2024, 15, 4887–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Li, G.; Tang, H.; Li, Y.; Lv, X.; Wang, X. Dung beetle optimization algorithm based on quantum computing and multi-strategy fusion for solving engineering problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Dhanalakshmi, R.; Akila, M.; Sinha, B.B. Improved equilibrium optimization based on Levy flight approach for feature selection. Evol. Syst. 2023, 14, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, J.; Kang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, K. State of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on modified flower pollination algorithm-temporal convolutional network. Energy 2023, 283, 128742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehchopogh, F.S.; Namazi, M.; Ebrahimi, L.; Abdollahzadeh, B. Advances in sparrow search algorithm: A comprehensive survey. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 427–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H.; Zamani, H.; Asghari Varzaneh, Z.; Mirjalili, S. A systematic review of the whale optimization algorithm: Theoretical foundation, improvements, and hybridizations. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 4113–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhao, D.; Heidari, A.A.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. RIME: A physics-based optimization. Neurocomputing 2023, 532, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Jaya: A simple and new optimization algorithm for solving constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2016, 7, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehab, M.; Mashal, I.; Momani, Z.; Shambour, M.K.Y.; AL-Badareen, A.; Al-Dabet, S.; Bataina, N.; Alsoud, A.R.; Abualigah, L. Harris hawks optimization algorithm: Variants and applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 5579–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umarani, S.; Balaji, N.A.; Balakrishnan, K.; Guptha, N. Binary northern goshawk optimization for feature selection on micro array cancer datasets. Evol. Syst. 2024, 15, 1551–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolamroudi, M.K.; Ilkan, M.; Egelioglu, F.; Safaei, B. Feature selection by ant colony optimization and experimental assessment analysis of PV panel by reflection of mirrors perpendicularly. Renew. Energy 2023, 218, 119238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S. Slime mould algorithm: A new method for stochastic optimization. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 111, 300–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Gorkemli, B.; Akay, B.; Karaboga, D. A review on the studies employing artificial bee colony algorithm to solve combinatorial optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghalipour, A.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Paydar, M.M. Tree Growth Algorithm (TGA): A novel approach for solving optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 72, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Houssein, E.H.; Mabrouk, M.S.; Al-Atabany, W.; Mirjalili, S. Henry gas solubility optimization: A novel physics-based algorithm. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 646–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; He, Y. A two-step image segmentation based on clone selection multi-object emperor penguin optimizer for fault diagnosis of power transformer. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 244, 122940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, S.; Zhou, C.; Yan, S. Manta ray foraging optimization based on mechanics game and progressive learning for multiple optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 145, 110561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm | Domain | Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISPSO [32] | High-dimensional feature selection, classification tasks | Accuracy reaches 93.5%, with redundant features reduced by approximately 12%. | Sensitive to initial parameter selection; requires high adaptability to specific high-dimensional scenarios; susceptible to feature dimensionality. |

| Dynamic PSO [33] | Feature selection for dynamic data streams | Accuracy ranges from 88% to 92%; capable of handling high-dimensional dynamic data. | Suitable for dynamic environments but struggles with real-time high-frequency changes; high computational resources. |

| SU-GA [34] | Feature selection for bioinformatics data | Average accuracy attains 91%. | Poor performance on small-scale datasets. |

| PSO-GWO [35] | Various domains in UCI repositories, hybrid feature selection | Average accuracy of 90% with reduced computation time. | Further research needed on alternative fitness and transfer functions. |

| Hybrid Ant Lion PSO [36] | Feature identification for gene expression data | Prediction accuracy of 87.88%. | Room for improvement in convergence rate for large-scale data processing. |

| EWOA [37] | Internet of Things (IoT) | Average accuracy of 95.5% on Aalto IoT dataset and 98.8% on RT-IoT 2022 dataset; average feature reduction rate of 82.5% (Aalto IoT) and 62.3% (RT-IoT 2022). | Prone to the curse of dimensionality due to initial parameters; excellent performance on static tasks but weak adaptability to dynamic data. |

| GOG-MBSHO [38] | Cancer gene feature selection, high-dimensional classification | Outperforms all comparative algorithms in average fitness value across selected datasets; average number of selected features is 63. | Risk of performance degradation when processing extremely large datasets. |

| I-KOA [39] | Liver disease classification, medical data feature selection | Overall classification accuracy of 93.46%; feature selection size of 0.1042. | High computational cost and insufficient algorithm adaptability. |

| HFCCW [40] | Network anomaly detection | Accuracy of 92%; feature selection rate ranges from 10% to 20%. | High computational time consumption. |

| Stage | HBO | IHBOFS |

|---|---|---|

| Population Initialization | ||

| Preservation Sub-population Update | - | |

| Crossover | ||

| Self-crossover | ||

| Population Sorting | ||

| Optimal Solution Update | ||

| Total |

| ID | Dataset | Number of Samples | Number of Features | Number of Classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | Yale | 165 | 1024 | 15 |

| D2 | ORL | 400 | 1024 | 10 |

| D3 | warpAR10P | 130 | 2400 | 40 |

| D4 | warpPIE10P | 210 | 2400 | 10 |

| D5 | pixraw10P | 100 | 10,000 | 10 |

| D6 | orlraws10P | 100 | 10,304 | 10 |

| Algorithms | Parameter Setting |

|---|---|

| HBO | |

| HBO_INIT | , |

| HBO_DE | , , |

| HBO_TD | , , |

| HBO_SC |

| Algorithms | Parameter Settings |

|---|---|

| IHBOFS | |

| GA | , |

| FPA | , |

| SSA | |

| WOA | b = 1 |

| RIME | W = 1.5 |

| JAYA | − |

| GWO | |

| HHO | = 1.5 |

| Function | HBO | HBO_INIT | HBO_DE | HBO_TD | HBO_SC | IHBOFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Std | Mean ± Std | Mean ± Std | Mean ± Std | Mean ± Std | Mean ± Std | |

| F1 | 310.55 ± 17.63 | 317.80 ± 47.96 | 316.91 ± 31.64 | 307.11 ± 13.78 | 4787.90 ± 1189.40 | 300.00 ± 0.00 |

| F2 | 465.03 ± 9.89 | 461.10 ± 10.63 | 459.11 ± 14.66 | 485.41 ± 19.14 | 588.89 ± 30.81 | 448.94 ± 0.75 |

| F3 | 600.00 ± 0.00 | 600.00 ± 0.00 | 600.00 ± 0.01 | 600.00 ± 0.00 | 600.00 ± 0.00 | 600.00 ± 0.00 |

| F4 | 930.62 ± 34.88 | 927.49 ± 26.82 | 914.28 ± 46.02 | 1048.30 ± 20.70 | 982.61 ± 31.13 | 878.03 ± 28.94 |

| F5 | 901.13 ± 0.61 | 900.23 ± 0.26 | 900.49 ± 0.35 | 902.36 ± 0.70 | 901.45 ± 0.64 | 900.24 ± 0.20 |

| F6 | 707,110 ± 565,160 | 1,445,900 ± 2,195,100 | 34,424 ± 12,929 | 23,070,000 ± 15,035,000 | 631,090 ± 991,950 | 45,885 ± 13,119 |

| F7 | 1951.40 ± 83.46 | 1980.70 ± 79.73 | 1955.40 ± 81.69 | 2192.60 ± 247.34 | 2067.40 ± 51.13 | 1987.40 ± 76.82 |

| F8 | 2887.40 ± 510.22 | 2984.00 ± 583.25 | 2303.90 ± 166.67 | 6223.30 ± 2264.10 | 3241.90 ± 352.97 | 2154.00 ± 101.03 |

| F9 | 2642.60 ± 7.06 | 2628.80 ± 61.09 | 2624.70 ± 60.27 | 2639.30 ± 2.23 | 2741.20 ± 123.17 | 2635.70 ± 0.05 |

| F10 | 2358.00 ± 887.07 | 2144.30 ± 1011.40 | 2480.90 ± 678.15 | 2577.20 ± 512.51 | 2847.50 ± 481.64 | 2527.60 ± 370.76 |

| F11 | 2613.90 ± 11.51 | 2612.50 ± 11.26 | 2615.60 ± 18.51 | 2623.30 ± 3.04 | 2609.50 ± 11.71 | 2600.00 ± 0.01 |

| F12 | 2939.40 ± 18.22 | 2942.70 ± 20.43 | 2927.80 ± 9.85 | 2929.40 ± 7.68 | 3068.50 ± 55.48 | 2900.00 ± 0.00 |

| Classifiers | Yale | ORL | warpAR10P | warpPIE10P | pixraw10P | orlraws10P | Average | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | TIME | ACC | TIME | ACC | TIME | ACC | TIME | ACC | TIME | ACC | TIME | ACC | TIME | |

| KNN | 64.85 | 0.04 | 87.25 | 0.06 | 49.23 | 0.05 | 93.33 | 0.06 | 95.00 | 0.08 | 90.00 | 0.08 | 79.94 | 0.0617 |

| SVM | 66.06 | 0.05 | 84.75 | 0.26 | 70.77 | 0.07 | 87.62 | 0.15 | 97.00 | 0.16 | 96.00 | 0.18 | 83.70 | 0.1450 |

| Xgboost | 60.61 | 0.92 | 75.00 | 3.84 | 68.46 | 1.34 | 84.76 | 1.51 | 80.00 | 1.93 | 72.00 | 3.39 | 73.47 | 2.1550 |

| DT | 49.52 | 0.31 | 23.40 | 0.97 | 69.54 | 0.32 | 69.29 | 0.65 | 89.60 | 0.61 | 74.10 | 1.14 | 62.58 | 0.6667 |

| RF | 70.12 | 1.16 | 75.90 | 1.16 | 78.54 | 1.16 | 86.48 | 1.16 | 95.80 | 1.16 | 96.30 | 1.17 | 83.86 | 1.1617 |

| NB | 63.64 | 0.05 | 88.25 | 0.09 | 59.23 | 0.06 | 87.14 | 0.07 | 22.00 | 0.16 | 93.00 | 0.16 | 68.88 | 0.0983 |

| KNN4 | 64.85 | 0.04 | 87.25 | 0.06 | 49.23 | 0.05 | 93.33 | 0.06 | 95.00 | 0.08 | 90.00 | 0.08 | 79.94 | 0.0617 |

| KNN5 | 62.42 | 0.04 | 83.50 | 0.06 | 43.08 | 0.05 | 90.48 | 0.06 | 96.00 | 0.08 | 89.00 | 0.08 | 77.41 | 0.0617 |

| KNN6 | 58.18 | 0.04 | 79.75 | 0.07 | 46.15 | 0.05 | 86.19 | 0.07 | 94.00 | 0.08 | 87.00 | 0.08 | 75.21 | 0.0650 |

| SVM3 | 63.64 | 0.05 | 82.25 | 0.27 | 64.62 | 0.07 | 81.90 | 0.15 | 96.00 | 0.16 | 93.00 | 0.18 | 80.24 | 0.1467 |

| SVM3.5 | 64.24 | 0.05 | 82.75 | 0.26 | 66.92 | 0.07 | 86.19 | 0.15 | 96.00 | 0.17 | 96.00 | 0.18 | 82.02 | 0.1467 |

| SVM4 | 66.06 | 0.05 | 84.75 | 0.26 | 70.77 | 0.07 | 87.62 | 0.15 | 97.00 | 0.16 | 96.00 | 0.18 | 83.70 | 0.1450 |

| Dataset | Measures (%) | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yale | Best | 80.00 | 80.00 | 81.21 | 80.00 | 79.39 | 80.00 | 79.39 | 78.79 |

| Worst | 78.18 | 78.18 | 78.79 | 78.18 | 75.76 | 75.76 | 76.36 | 75.15 | |

| Mean | 79.33 | 79.27 | 80.12 | 79.45 | 77.45 | 77.27 | 77.58 | 77.03 | |

| Std | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 1.11 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.26 | |

| ORL | Best | 93.00 | 92.00 | 93.00 | 93.00 | 91.50 | 91.00 | 92.00 | 91.25 |

| Worst | 90.75 | 90.50 | 91.75 | 91.25 | 89.75 | 89.55 | 89.75 | 89.75 | |

| Mean | 91.33 | 91.25 | 92.35 | 92.23 | 90.73 | 90.25 | 90.50 | 90.30 | |

| Std | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.72 | 0.46 | |

| warpAR10P | Best | 85.38 | 86.92 | 86.15 | 87.69 | 84.62 | 84.62 | 86.92 | 83.85 |

| Worst | 81.54 | 82.31 | 83.85 | 82.31 | 80.77 | 79.23 | 80.77 | 80.77 | |

| Mean | 84.15 | 84.23 | 85.15 | 84.38 | 82.15 | 82.38 | 83.08 | 82.38 | |

| Std | 1.10 | 1.34 | 0.60 | 1.62 | 1.13 | 1.52 | 1.65 | 1.11 | |

| warpPIE10P | Best | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.52 | 99.05 | 99.52 | 99.52 | 98.10 |

| Worst | 97.14 | 97.14 | 97.62 | 97.14 | 95.71 | 95.24 | 96.67 | 94.76 | |

| Mean | 98.52 | 98.38 | 98.81 | 98.52 | 97.05 | 97.48 | 97.71 | 96.52 | |

| Std | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 1.22 | 1.51 | 0.92 | 1.04 | |

| pixraw10P | Best | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Worst | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | |

| Mean | 99.40 | 99.60 | 99.50 | 99.60 | 99.50 | 99.60 | 99.40 | 99.60 | |

| Std | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | |

| orlraws10P | Best | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Worst | 98.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 98.00 | 99.00 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 98.00 | |

| Mean | 99.50 | 99.50 | 99.50 | 99.20 | 99.30 | 98.80 | 99.00 | 99.00 | |

| Std | 0.81 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.63 |

| Transfer Functions | Yale | ORL | warpAR10P | warpPIE10P | pixraw10P | orlraws10P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg | Std | Avg | Std | Avg | Std | Avg | Std | Avg | Std | Avg | Std | |

| S1 | 409.10 | 31.49 | 410.60 | 50.08 | 454.10 | 176.20 | 430.20 | 159.87 | 24.00 | 9.86 | 138.90 | 188.01 |

| S2 | 397.60 | 48.38 | 451.00 | 42.01 | 474.90 | 233.89 | 430.00 | 205.92 | 27.90 | 13.49 | 91.00 | 38.04 |

| S3 | 361.70 | 77.88 | 420.70 | 25.98 | 472.00 | 131.48 | 253.60 | 117.91 | 20.00 | 5.39 | 110.40 | 68.14 |

| S4 | 408.40 | 51.10 | 364.50 | 70.05 | 419.30 | 202.34 | 351.20 | 155.36 | 21.30 | 6.07 | 154.90 | 119.42 |

| V1 | 262.60 | 59.37 | 373.10 | 68.78 | 400.40 | 208.35 | 430.10 | 264.03 | 39.30 | 15.32 | 123.70 | 55.84 |

| V2 | 287.30 | 66.58 | 408.70 | 69.11 | 458.80 | 204.12 | 332.40 | 261.49 | 45.10 | 28.07 | 132.70 | 53.86 |

| V3 | 290.20 | 80.84 | 401.40 | 50.58 | 386.50 | 137.02 | 218.90 | 93.76 | 40.30 | 31.87 | 151.10 | 92.95 |

| V4 | 313.10 | 71.76 | 405.90 | 50.04 | 417.60 | 141.61 | 418.30 | 232.10 | 41.80 | 26.16 | 155.40 | 105.44 |

| Datasets | Algorithms | Best | Worst | Mean | Std | Num | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | HBO | 78.79 | 76.36 | 77.58 | 0.61 | 351.6 | 94.47 |

| IHBOFS | 81.21 | 78.79 | 80.12 | 0.59 | 361.70 | 88.69 | |

| HHO | 75.76 | 71.52 | 73.39 | 1.34 | 238.30 | 194.68 | |

| ACO | 75.76 | 72.12 | 73.58 | 1.09 | 464.80 | 100.05 | |

| SMA | 71.52 | 69.09 | 70.18 | 0.76 | 89.60 | 96.89 | |

| ABC | 75.15 | 71.52 | 74.00 | 1.03 | 418.70 | 201.66 | |

| TGA | 72.12 | 69.70 | 70.85 | 0.69 | 504.80 | 110.49 | |

| HGSO | 70.30 | 69.09 | 69.88 | 0.39 | 493.20 | 103.12 | |

| EPO | 73.33 | 70.91 | 72.06 | 0.88 | 63.60 | 58.53 | |

| MRFO | 77.58 | 72.12 | 76.06 | 1.52 | 246.60 | 192.29 | |

| D2 | HBO | 91.50 | 89.75 | 90.72 | 0.55 | 384.20 | 472.91 |

| IHBOFS | 93.00 | 91.75 | 92.35 | 0.44 | 420.70 | 447.11 | |

| HHO | 90.50 | 87.50 | 88.63 | 1.13 | 281.90 | 1040.11 | |

| ACO | 90.25 | 87.50 | 88.92 | 0.74 | 479.00 | 521.61 | |

| SMA | 87.50 | 85.00 | 85.67 | 0.68 | 113.10 | 440.60 | |

| ABC | 89.75 | 89.25 | 89.47 | 0.21 | 457.90 | 1046.83 | |

| TGA | 87.00 | 85.75 | 86.28 | 0.36 | 503.40 | 567.56 | |

| HGSO | 86.75 | 85.25 | 85.83 | 0.45 | 506.40 | 514.93 | |

| EPO | 87.75 | 85.25 | 86.78 | 0.79 | 112.90 | 293.91 | |

| MRFO | 91.50 | 88.00 | 89.15 | 0.97 | 339.20 | 990.85 | |

| D3 | HBO | 83.85 | 80.00 | 81.31 | 1.09 | 751.60 | 119.10 |

| IHBOFS | 86.15 | 83.85 | 85.15 | 0.60 | 472.00 | 108.14 | |

| HHO | 83.08 | 78.46 | 80.92 | 1.75 | 280.10 | 210.61 | |

| ACO | 79.23 | 76.92 | 78.08 | 0.71 | 1093.70 | 126.27 | |

| SMA | 80.00 | 75.38 | 76.85 | 1.21 | 41.90 | 108.36 | |

| ABC | 79.23 | 77.69 | 78.38 | 0.41 | 1059.10 | 253.99 | |

| TGA | 76.92 | 74.62 | 76.08 | 0.64 | 1186.90 | 141.09 | |

| HGSO | 76.92 | 73.85 | 75.23 | 0.83 | 1190.60 | 127.22 | |

| EPO | 83.08 | 76.15 | 80.15 | 2.25 | 34.00 | 74.33 | |

| MRFO | 83.08 | 79.23 | 80.92 | 1.23 | 432.90 | 237.55 | |

| D4 | HBO | 98.10 | 94.29 | 95.81 | 1.04 | 765.30 | 230.18 |

| IHBOFS | 100.00 | 97.62 | 98.81 | 0.86 | 253.60 | 190.31 | |

| HHO | 97.62 | 95.71 | 96.43 | 0.65 | 115.10 | 359.06 | |

| ACO | 94.29 | 91.90 | 93.19 | 0.74 | 1109.20 | 250.45 | |

| SMA | 94.76 | 90.95 | 92.95 | 1.12 | 45.40 | 171.51 | |

| ABC | 94.76 | 92.86 | 93.48 | 0.71 | 1078.30 | 491.03 | |

| TGA | 92.38 | 90.95 | 91.62 | 0.49 | 1203.90 | 277.40 | |

| HGSO | 91.43 | 90.48 | 90.09 | 0.26 | 1203.20 | 236.71 | |

| EPO | 95.71 | 93.33 | 94.43 | 0.80 | 40.60 | 107.09 | |

| MRFO | 99.05 | 92.86 | 96.67 | 1.92 | 313.90 | 350.61 | |

| D5 | HBO | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 0.00 | 1716.90 | 308.34 |

| IHBOFS | 100.00 | 99.00 | 99.50 | 0.50 | 20.00 | 212.40 | |

| HHO | 100.00 | 99.00 | 99.10 | 0.30 | 23.00 | 350.00 | |

| ACO | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 0.00 | 4523.60 | 322.90 | |

| SMA | 100.00 | 99.00 | 99.50 | 0.50 | 16.90 | 266.08 | |

| ABC | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 0.00 | 4480.80 | 661.02 | |

| TGA | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 0.00 | 4917.50 | 365.06 | |

| HGSO | 99.00 | 98.00 | 98.90 | 0.30 | 4958.10 | 298.39 | |

| EPO | 100.00 | 99.00 | 99.30 | 0.46 | 13.60 | 134.40 | |

| MRFO | 100.00 | 99.00 | 99.60 | 0.49 | 31.50 | 372.00 | |

| D6 | HBO | 98.00 | 97.00 | 97.80 | 0.40 | 1830.80 | 330.51 |

| IHBOFS | 100.00 | 99.00 | 99.50 | 0.50 | 110.40 | 256.00 | |

| HHO | 100.00 | 98.00 | 98.90 | 0.70 | 47.30 | 383.50 | |

| ACO | 98.00 | 97.00 | 97.70 | 0.46 | 4730.30 | 349.58 | |

| SMA | 100.00 | 98.00 | 98.60 | 0.66 | 45.20 | 270.70 | |

| ABC | 98.00 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 0.00 | 4670.80 | 716.17 | |

| TGA | 98.00 | 97.00 | 97.40 | 0.49 | 5080.50 | 397.87 | |

| HGSO | 97.00 | 97.00 | 97.00 | 0.00 | 5107.60 | 338.67 | |

| EPO | 100.00 | 98.00 | 98.70 | 0.90 | 28.40 | 140.43 | |

| MRFO | 100.00 | 98.00 | 99.00 | 0.77 | 110.20 | 445.54 |

| Algorithm | Average Ranking | Final Rank | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IHBOFS | 1.166667 | 1 | 8.182420 × 10−10 |

| MRFO | 2.666667 | 2 | |

| HBO | 3.833333 | 3 | |

| HHO | 4.333333 | 4 | |

| EPO | 5.333333 | 5 | |

| ABC | 5.500000 | 6 | |

| ACO | 6.500000 | 7 | |

| SMA | 7.166667 | 8 | |

| TGA | 8.666667 | 9 | |

| HGSO | 9.833333 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiang, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, W. IHBOFS: A Biomimetics-Inspired Hybrid Breeding Optimization Algorithm for High-Dimensional Feature Selection. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010003

Xiang C, Zhou J, Zhou W. IHBOFS: A Biomimetics-Inspired Hybrid Breeding Optimization Algorithm for High-Dimensional Feature Selection. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Chunli, Jing Zhou, and Wen Zhou. 2026. "IHBOFS: A Biomimetics-Inspired Hybrid Breeding Optimization Algorithm for High-Dimensional Feature Selection" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010003

APA StyleXiang, C., Zhou, J., & Zhou, W. (2026). IHBOFS: A Biomimetics-Inspired Hybrid Breeding Optimization Algorithm for High-Dimensional Feature Selection. Biomimetics, 11(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010003