Biomimetic Assessment of 3D-Printed T-Shape Joints Bio-Inspired by the Stem-Branch Junction in Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) Trees

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. 3D Printing

2.3. X-Ray Micro-CT Imaging

2.4. Mechanical Tests and Data Processing

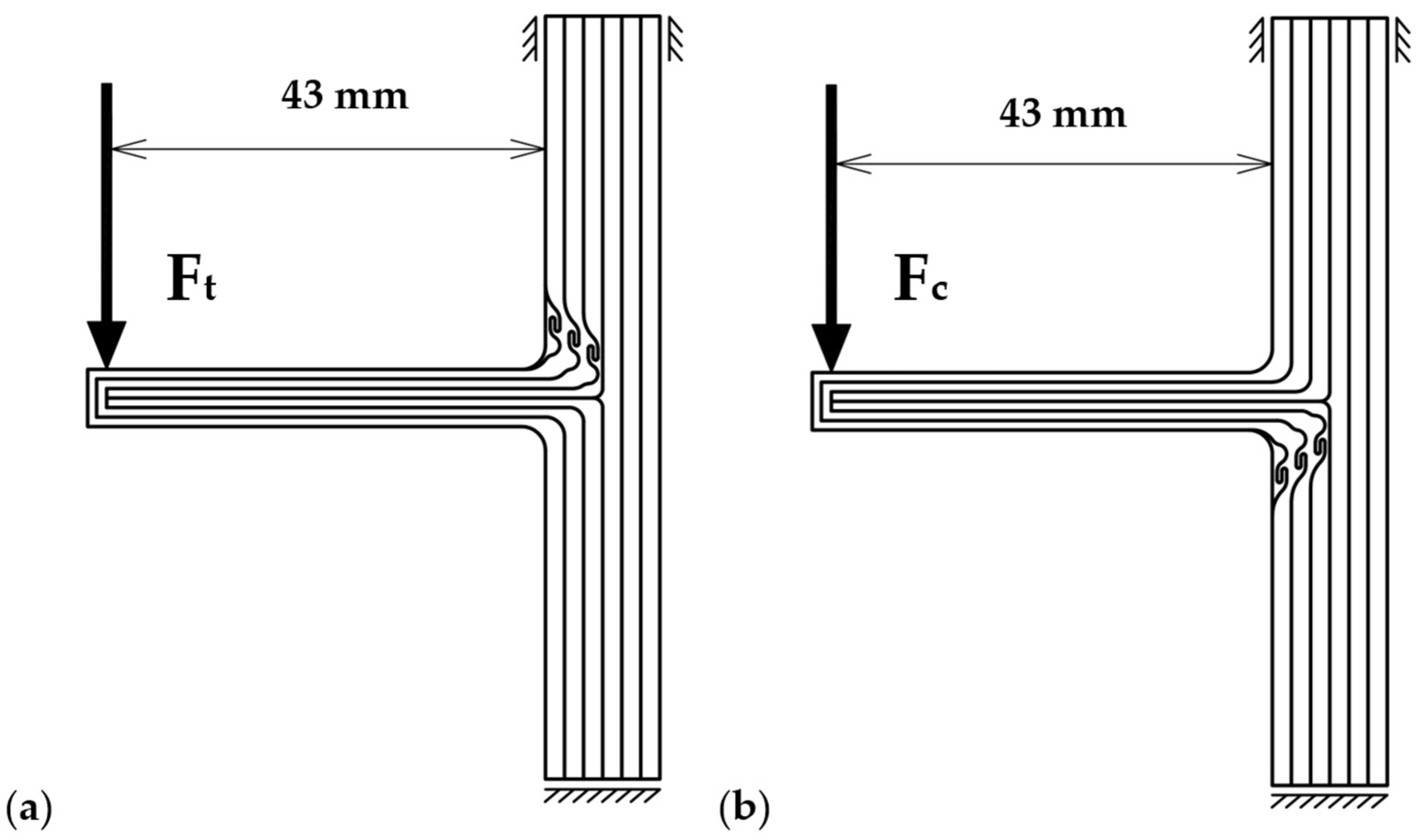

2.5. Mechanical Testing of 3D-Printed Samples

2.6. FEM of the Artificial 3D-Printed Samples

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Micro-CT Imaging

3.2. Mechanics of Branches

3.3. Mechanical Testing of 3D-Printed Joints

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ILA | Interlocked area |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| T-joint | T-shaped joint of two elements |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| micro-CT | Computed tomography at a microscopic level |

| 3D | Three dimensional |

| PETG | Polyethylene terephthalate glycol |

| MOE | Modulus of elasticity |

References

- Buck, N.T. The Art of Imitating Life: The Potential Contribution of Biomimicry in Shaping the Future of Our Cities. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2017, 44, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayemi, P.E.; Wanieck, K.; Zollfrank, C.; Maranzana, N.; Aoussat, A. Biomimetics: Process, Tools and Practice. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2017, 12, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, L.; Mouritz, A.P.; Pook, D.; Feih, S. Bio-Inspired Hierarchical Design of Composite T-Joints with Improved Structural Properties. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 69, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawasly, F.; Matsumoto, N.; Koshihara, M. Bio-Inspired Wood-Only Timber Frame Joint Typologies Based on the Seamless Fiber Continuities of a Tree’s Stem-Branch Junction. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 2021, 9, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Gindl, W.; Jeronimidis, G. Biomechanics of a Branch–Stem Junction in Softwood. Trees 2006, 20, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, D.; Ennos, A.R. Interlocking Wood Grain Patterns Provide Improved Wood Strength Properties in Forks of Hazel (Corylus avellana L.). Int. J. Urban For. 2015, 37, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungnikl, K.; Goebbels, J.; Burgert, I.; Fratzl, P. The Role of Material Properties for the Mechanical Adaptation at Branch Junctions. Trees 2009, 23, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, E.M.; Borkowski, M.H. Wood Grain Patterns at Branch Junctions: Modeling and Implications. Trees 2004, 18, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Brigget, A.; Olsson, A.; Johansson, M.; Oscarsson, J.; Säll, H. Growth Layer and Fibre Orientation Around Knots in Norway Spruce: A Laboratory Investigation. Wood Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Olsson, A.; Hall, S.; Seifer, T. Fibre Directions at a Branch–Stem Junction in Norway Spruce: A Microscale Investigation Using X-Ray Computed Tomography. Wood Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun, S.; Aloni, R. Vascular Differentiation in Branch Junctions of Trees: Circular Patterns and Functional Significance. Trees 1990, 4, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, D.; Bradley, R.S.; Withers, P.J.; Ennos, A.R. The Anatomy and Grain Pattern in Forks of Hazel (Corylus avellana L.) and Other Tree Species. Trees 2014, 28, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.; Hosseini, M.S.; Restrepo, D.; Murata, S.; Vasile, D.; Parkinson, D.Y.; Barnard, H.S.; Arakaki, A.; Zavattieri, P.; Kisailus, D. Toughening Mechanisms of the Elytra of the Diabolical Ironclad Beetle. Nature 2020, 586, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, Z.; Yazdani Sarvestani, H.; Gholipour Baradari, J.; Ashrafi, B. Bioinspired Hierarchical Ceramic Sutures for Multi-Modal Performance. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2300098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiawan, R.; Imaduddin, F.; Ariawan, D.; Ubaidillah, U.; Arifin, Z. A Review on the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D Printing: Filament Processing, Materials, and Printing Parameters. Open Eng. 2021, 11, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Chhabra, D.; Gupta, R.K.; Phogat, A.; Ahlawat, A. Modeling and Analysis of Significant Process Parameters of FDM 3D Printer Using ANFIS. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 21, 1592–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, R.; Ranganathan, R.; Sreebalaji, V.S.; Munusamy, S. Exploring the Impact of Surface Modifications on the Mechanical Characteristics of Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene Parts Manufactured Using Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 3811–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafeez, A.; Abdelrhman, Y.; Soliman, M.-E.; Ahmed, S.M. Comparative Effects of Carbon Fiber Reinforcement on Polypropylene and Polylactic Acid Composites in Fused Deposition Modeling. J. Eng. Sci. 2025, 53, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quader, R.; Narayanan, L.K. Effect of In-Situ Layer Scanning Ultrasonic Vibration on Mechanical and Morphological Properties of Fused Deposition Modeled Poly(Lactic) Acid Specimens. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 133, 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Z. Effect of Interlocking Structure on Mechanical Properties of Bio-Inspired Nacreous Composites. Compos. Struct. 2019, 226, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djumas, L.; Molotnikov, A.; Simon, G.P.; Estrin, Y. Enhanced Mechanical Performance of Bio-Inspired Hybrid Structures Utilising Topological Interlocking Geometry. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, D. Biomimicry Resource Handbook: A Seed Bank of Best Practices; Biomimicry 3.8; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Missoula, MT, USA, 2014; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Karadžić, D.; Stanivuković, Z.; Milanović, S.; Sikora, K.; Radulović, Z.; Račko, V.; Kardošová, M.; Ďurkovič, J.; Milenković, I. Development of Neonectria punicea Pathogenic Symptoms in Juvenile Fraxinus excelsior Trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 592260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorov, A.; Beichel, R.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Finet, J.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pujol, S.; Bauer, C.; Jennings, D.; Fennessy, F.M.; Sonka, M.; et al. 3D Slicer as an Image Computing Platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 30, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckelman, C.; Haviarova, E.; Erdil, Y.Z.; Tankut, A.N.; Akcay, H.; Denizli Tankut, N. Bending Moment Capacity of Round Mortise and Tenon Furniture Joints. For. Prod. J. 2004, 54, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Eckelman, C.; Erdil, Y.Z.; Haviarova, E. Effect of Shoulders on Bending Moment Capacity of Round Mortise and Tenon Joints. For. Prod. J. 2006, 56, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dizon, J.R.C.; Espera, A.H.; Chen, Q.; Advincula, R.C. Mechanical Characterization of 3D-Printed Polymers. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 20, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, R.J.M.; Šavija, B. Micromechanical Models for FDM 3D-Printed Polymers: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, A.; Abali, B.E.; Völlmecke, C.; Gerstel, J.; Auhl, D. Exploring the Role of Manufacturing Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties in Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) Using PETG. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2021, 28, 1799–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvez, S.; Silva, A.P.; Reis, P.N.B. Optimization of Printing Parameters to Maximize the Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed PETG-Based Parts. Polymers 2022, 14, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, M.-H.; Lai, C.-J.; Wang, S.-H.; Zeng, Y.-S.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Pan, C.-Y.; Huang, W.-C. Effect of Printing Parameters on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed PLA and PETG, Using Fused Deposition Modeling. Polymers 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgashyam, K.; Reddy, M.I.; Balakrishna, A.; Satyanarayana, K. Experimental Investigation on Mechanical Properties of PETG Material Processed by Fused Deposition Modeling Method. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 2052–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, K.L. Pruning Wounds and Occlusion: A Long-Standing Conundrum in Forestry. J. For. 2007, 105, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somireddy, M.; Czekanski, A.; Shrimpton, J. Flexural Behavior of FDM Parts: Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 15, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, Y.; Fang, J. Orthotropic mechanical properties of PLA materials fabricated by fused deposition modeling. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 199, 111800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeid, A.A.; Donaldson, S.L. Experimental and Finite Element Investigations of Damage Resistance in Biomimetic Composite Sandwich T-Joints. Materials 2016, 9, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type * | Valid N | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| c | 21 | 932 | 417 |

| t | 21 | 989 | 404 |

| SRbranch | 21 | 1.018 | 0.037 |

| Variable | Type | Valid N | Asymmetrical | Symmetrical | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no_ILA | ILA | no_ILA | ILA | |||

| MOE, MPa | t | 10 | 1658 | 1674 | 1657 | 1611 |

| (1.7%) | (2.0%) | (1.4%) | (3.3%) | |||

| c | 10 | 1682 | 1653 | 1658 | 1656 | |

| (2.0%) | (1.9%) | (2.1%) | (1.8%) | |||

| SR3D | t/c | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.97 | |

| Strength, MPa | t | 10 | 68.85 | 70.48 | 70.80 | 71.48 |

| (2.1%) | (1.4%) | (3.6%) | (3.2%) | |||

| c | 10 | 71.41 | 71.97 | 71.99 | 71.79 | |

| (2.9%) | (1.6%) | (2.6%) | (2.2%) | |||

| y max, mm | t | 10 | 12.10 | 11.16 | 13.08 | 12.86 |

| 5.6% | 7.4% | 3.1% | 2.7% | |||

| c | 10 | 12.09 | 12.19 | 13.16 | 12.68 | |

| 4.8% | 3.3% | 6.6% | 2.1% | |||

| y at 16 N, mm | t | 10 | 3.10 | 3.09 | 3.17 | 3.19 |

| 1.5% | 1.9% | 2.8% | 2.2% | |||

| c | 10 | 3.09 | 3.15 | 3.21 | 3.17 | |

| 1.1% | 1.3% | 3.2% | 1.0% | |||

| y at 16 N, mm | FEM t | 1 | 3.648 | 3.581 | 3.564 | 3.719 |

| FEM c | 1 | 3.572 | 3.538 | 3.564 | 3.658 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lagaňa, R.; Nôta, R.; Tončíková, Z.; Holeček, T.; Langová, N.; Ďurkovič, J. Biomimetic Assessment of 3D-Printed T-Shape Joints Bio-Inspired by the Stem-Branch Junction in Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) Trees. Biomimetics 2026, 11, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010015

Lagaňa R, Nôta R, Tončíková Z, Holeček T, Langová N, Ďurkovič J. Biomimetic Assessment of 3D-Printed T-Shape Joints Bio-Inspired by the Stem-Branch Junction in Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) Trees. Biomimetics. 2026; 11(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleLagaňa, Rastislav, Roman Nôta, Zuzana Tončíková, Tomáš Holeček, Nadežda Langová, and Jaroslav Ďurkovič. 2026. "Biomimetic Assessment of 3D-Printed T-Shape Joints Bio-Inspired by the Stem-Branch Junction in Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) Trees" Biomimetics 11, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010015

APA StyleLagaňa, R., Nôta, R., Tončíková, Z., Holeček, T., Langová, N., & Ďurkovič, J. (2026). Biomimetic Assessment of 3D-Printed T-Shape Joints Bio-Inspired by the Stem-Branch Junction in Common Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) Trees. Biomimetics, 11(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics11010015