3.3.1. Bio-Inspired Handover Motion Planning Strategy for the Robot

Being inspired by the results of experiment 1, a novel trust-based handover motion planning strategy for the robot was proposed in this section. We assume that a real-time or nearly real-time measure of robot trust in its human co-worker was given. Then, the objective was to use the computed robot trust values to modify and adjust the handover behaviors of the robot, i.e., modify the robot’s motion and configuration during object handover [

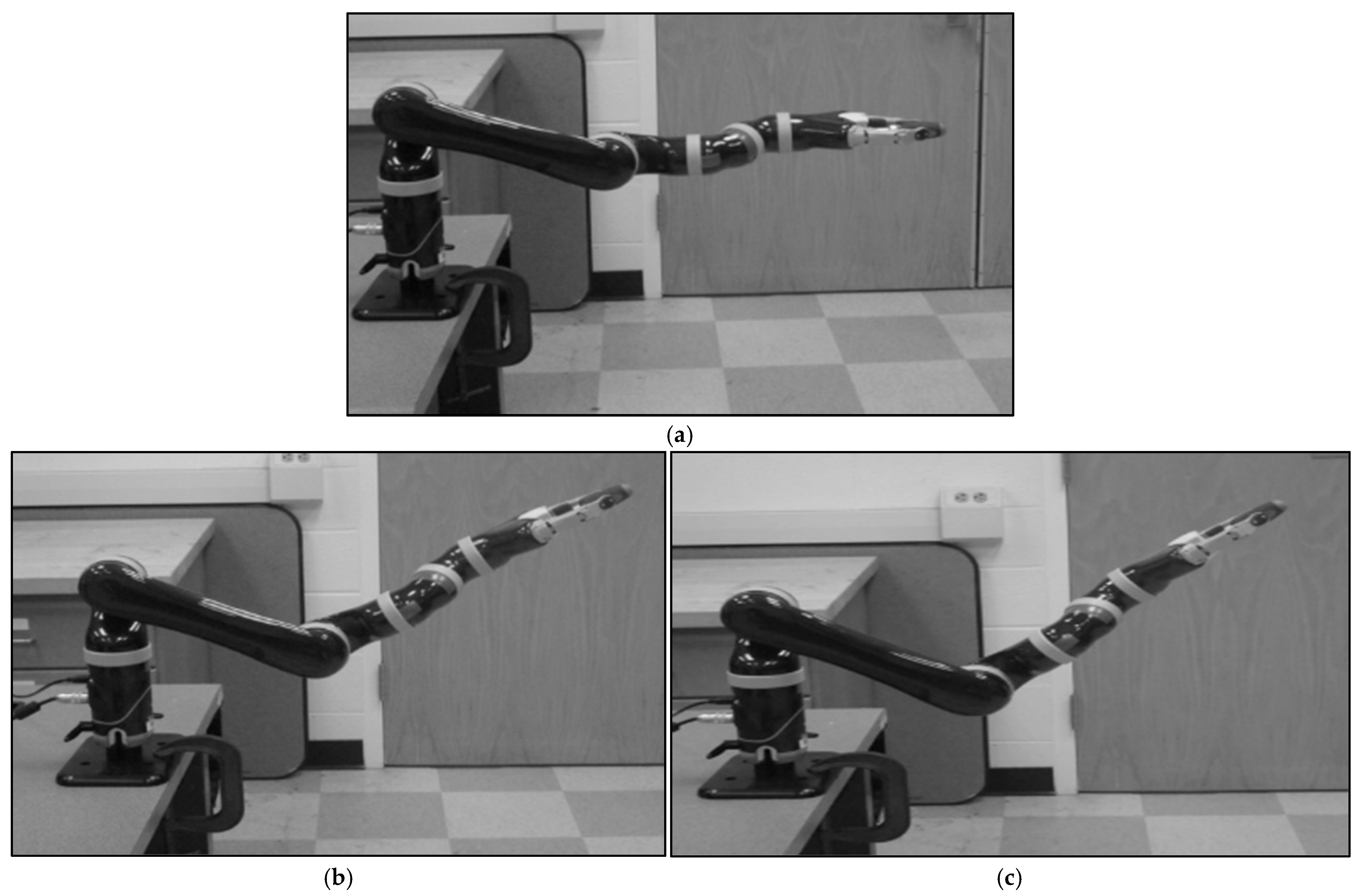

42]. We divided the handover motion planning of the robot into two different categories: (i) normal or default handover, and (ii) corrective or adjusted handover. The robot’s handover motion and configuration were considered normal or default (human hand was to be in parallel/co-linear with the robot end effector) when the robot’s trust in its human co-worker remained high, as shown in

Figure 2a [

42]. In this condition, the robot would follow the preplanned task-optimal handover trajectory, which would be safe for the human co-worker because the human might be in a well-planned situation and thus would be aware of potential impulse forces since the human would maintain high robot trust in them through their high performance and reduced faults during the handover. However, when robot trust in humans drops to below a pre-specified threshold, we might need to correct or adjust the robot’s handover motion trajectory based on the computed trust values, as shown in

Figure 2b. As the figure shows, when robot trust in humans is reduced from high to medium, the robot would try to generate a partial braced handover configuration with reduced handover motion to mitigate the potential impulse forces generated during the handover. When robot trust in humans is low, it means that humans would not be in a good position to collaborate with the robot, i.e., humans would be unprepared for the collaboration. As a result, if the robot handed an object over to the human, the human might be unable to receive the object properly. It means, in the low robot trust in the human, the human might prove unreliable to receive the object. If the robot handed an object over to the human when the human was unprepared and unreliable, impulse or impact forces due to unplanned and unwanted relative motions between the human hand and the robot end effector via the object might be generated during the handover, and the forces might be exerted on the human hand via the object. Such impulse forces might be unsafe for the human’s occupational health and safety and for the successful completion of the handover task (the payload might drop off, or it might be damaged). As a result, the robot would generate a braced configuration with a reduced handover speed (cautious trajectory) to mitigate potential impulse forces, as

Figure 2c illustrates [

42].

A robot manipulator may have high accuracy and repeatability in motion planning, including handover motion planning. As a result, the robot can generate normal handover motion even when its trust in the collaborating human becomes low. However, we cannot directly control or adjust the handover motion of the human co-worker because the human’s handover motion planning is related to human psychology. As a result, to mitigate or minimize the effects of unwanted relative motion and resulting impulse forces for the condition when the robot’s trust in the human becomes low, we may adopt a novel handover motion planning strategy for the robot itself, as

Figure 2 illustrates. The novel handover motion planning strategy for the robot may be such that the robot itself may take an initiative to control its own handover motion to minimize the effects of potential impulse forces resulting from relative motions (unexpected contact between the human hand and robot end effector through the object) when robot trust in the human becomes low [

42]. To realize this novel handover motion planning strategy for the robot, we here adopt a two-fold approach: (i) the robot follows a ‘cautious’ handover motion, which is such that the robot slows down the handover motion, and (ii) the robot forms a ‘braced configuration’ when handing over an object to the human. It is assumed that the slow motion and the braced handover configuration can avoid or minimize potential collision and the resulting impulse forces in the direction of the human co-worker receiving an object (payload) from the robot during the handover operation when the robot’s trust in the human is low. This strategy may slightly reduce the efficiency of the handover task, but it may enhance overall safety and productivity of the assembly task involving object handover operations [

73]. Taking inspiration from

Table 3, the absolute velocities for the handover configurations in

Figure 2a–c were empirically decided as 0.7, 0.6, and 0.4 of the robot arm’s maximum speed (1.0), respectively.

3.3.3. Experimental Protocols and Procedures

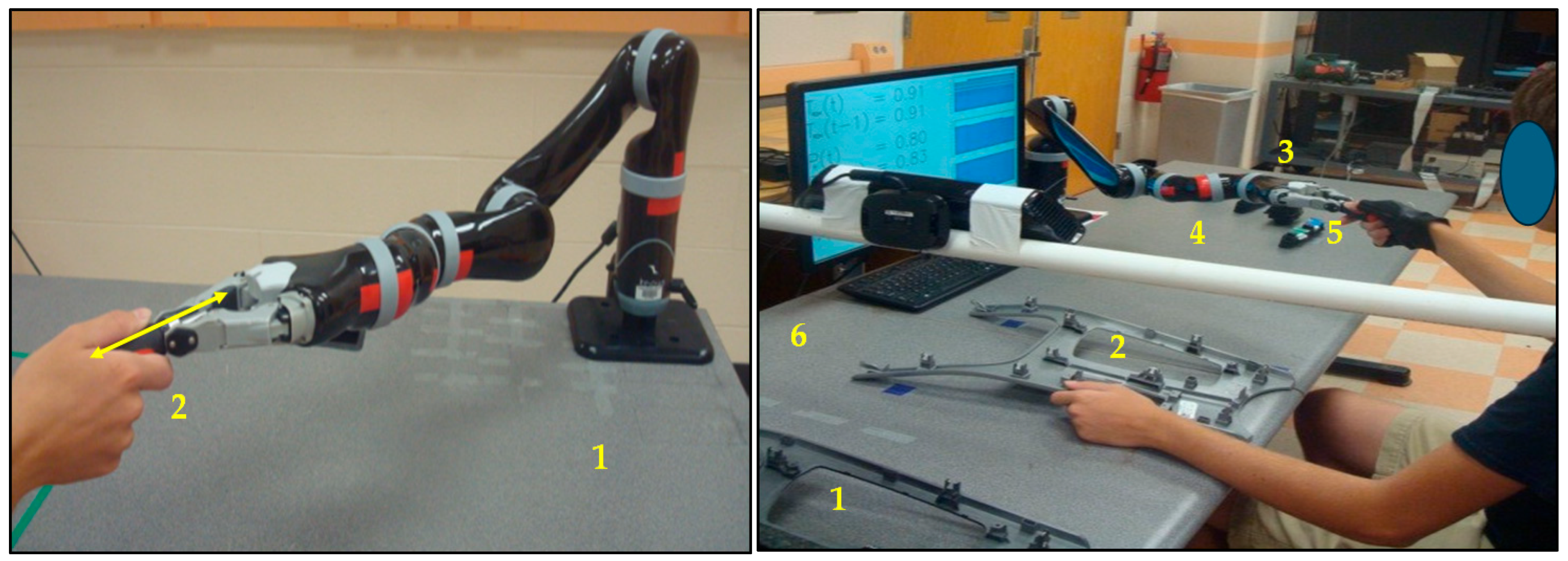

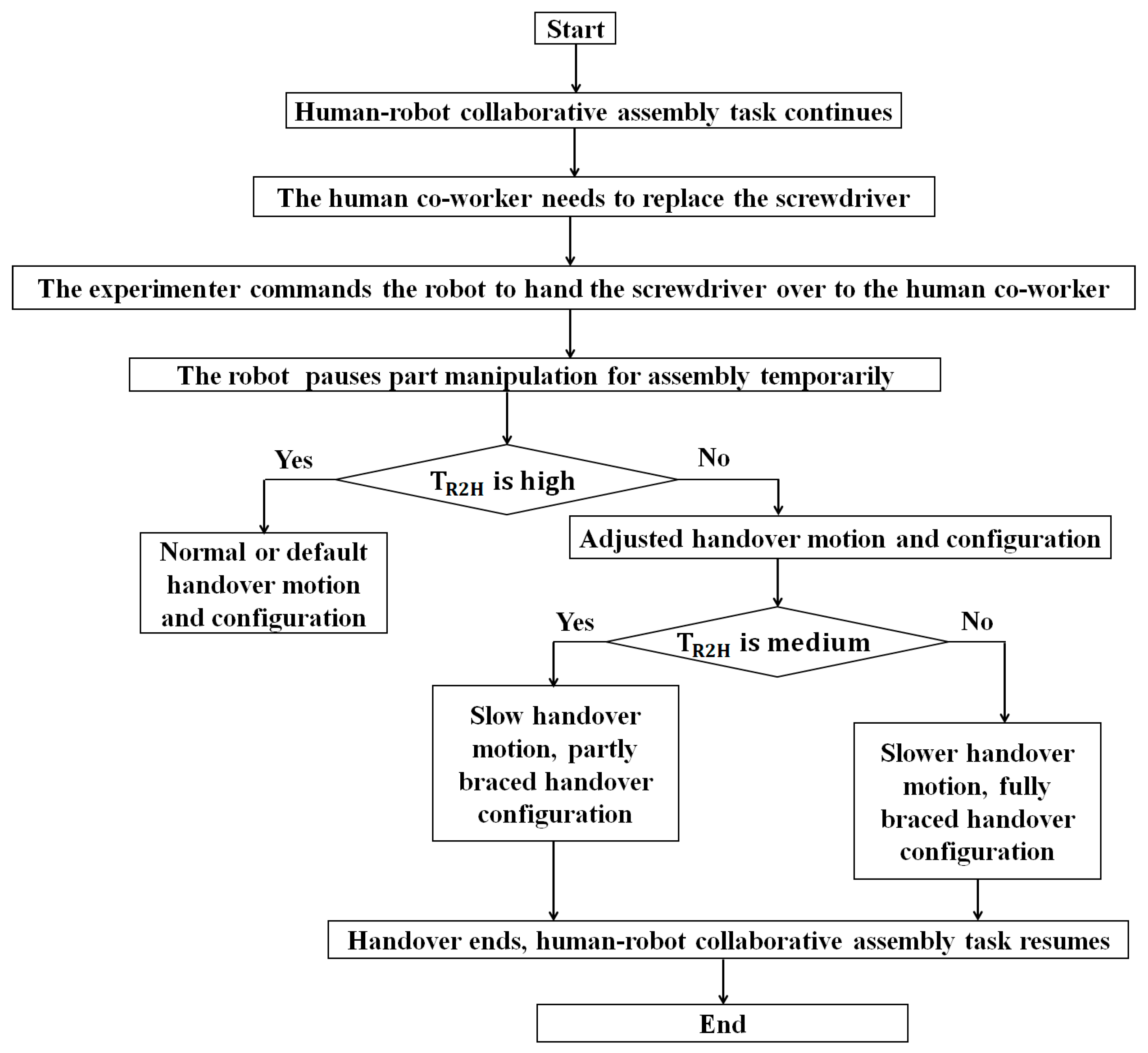

The objective of this experiment was to evaluate the effectiveness of the bio-inspired robot-to-human object handover algorithm proposed in

Figure 4 in a human–robot collaborative assembly task setup as introduced in

Figure 1 (right). In this experiment, we used the same human subjects that we used in experiment 1. Each subject separately conducted the collaborative assembly task with the robot, and the assembly task also included a robot-to-human handover operation. There were two experimental protocols, as follows:

- (i).

The collaborative assembly task, including a robot-to-human handover operation, was executed, and the handover followed the handover configurations introduced in

Figure 2 and the algorithm introduced in

Figure 4, depending on computed robot trust values. We call this experimental protocol “Bio-inspired (trust-triggered) handover”.

- (ii).

The collaborative assembly task, including a robot-to-human payload handover operation, was executed, but the handover did not follow the algorithm introduced in

Figure 4 (i.e., the robot used the default or normal handover motion and configuration as

Figure 2a demonstrates. We call this experimental protocol “Default handover”.

For the assembly task associated with bio-inspired handover, human subjects and the robot performed the collaborative assembly, including a handover event, following

Figure 1 (right). Each subject separately performed the assembly task with the robot based on the subtask allocation for 5 min, following the same procedures as described in Experiment 1.

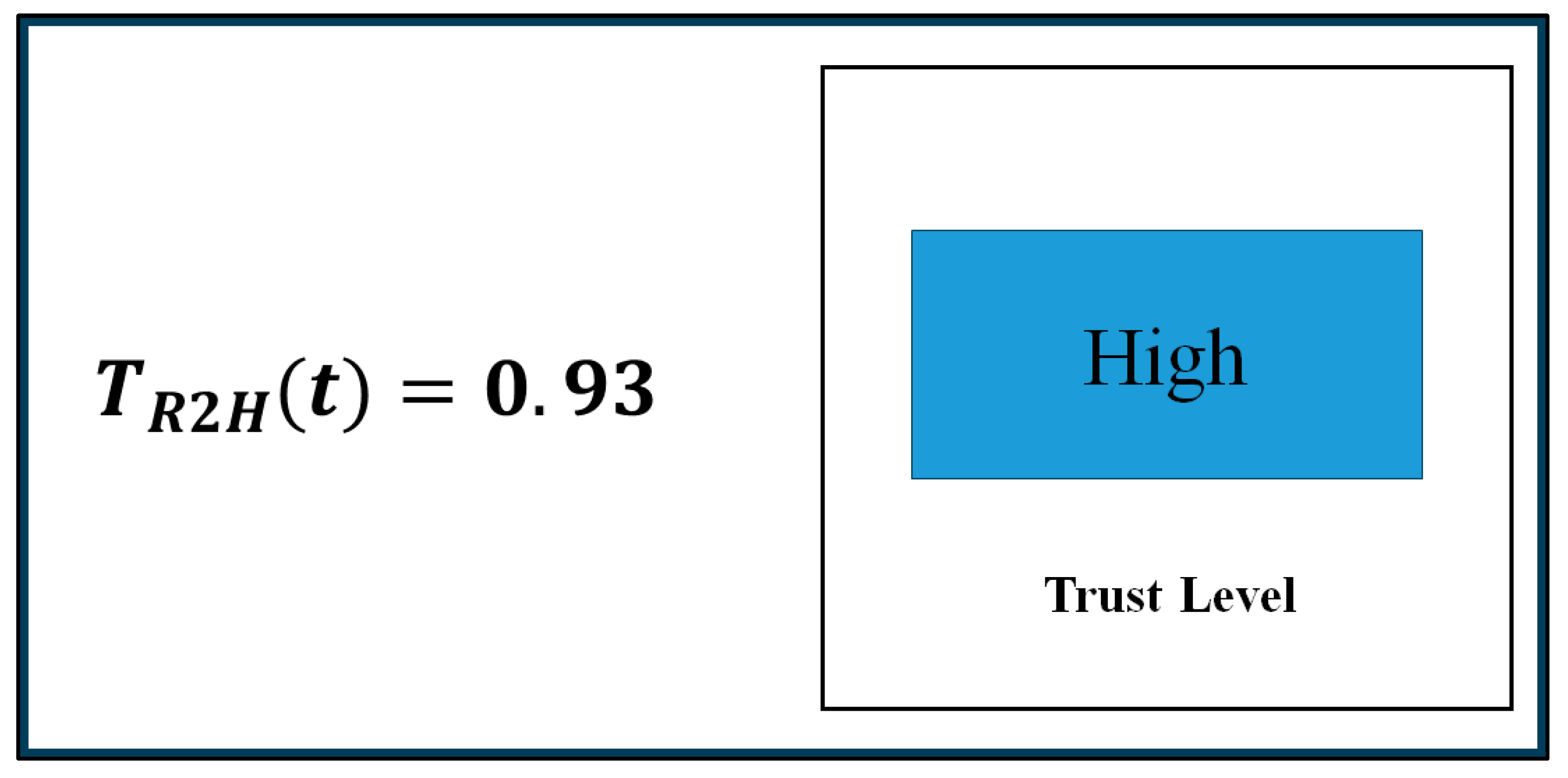

was measured and displayed on the screen in real time (see

Figure 3). While the assembly operation was going on, the experimenter randomly decided a time during the assembly and asked the human subject to use a new screwdriver, replacing the existing screwdriver. The subject then sent a handover command to the robot by pushing the “Enter” key on the keyboard. The robot then stopped manipulating assembly parts and moved to pick the screwdriver from a corner of the table, manipulated it to the human, and handed it over to the human, as

Figure 1 (right) demonstrates. The robot followed one of the three handover configurations (

Figure 2a–c) with corresponding handover motions (normal/fast, slow, or very slow motion) based on the computed robot trust (value) in the human at that time step, according to the algorithm demonstrated in

Figure 4. At the end of the handover trial, the assembly operation resumed. At the end of the assembly task, we evaluated the collaborative assembly task, including the handover operation, following a comprehensive evaluation scheme, as follows. Each subject took part in the experiment separately, and they were selected for the experiment randomly.

For the assembly task without an associated bio-inspired handover (default handover), the above procedures were repeated, and

was measured and displayed in real time (

Figure 3). However, the robot handed over the screwdriver to the human following a fixed (default) handover configuration and motion as illustrated in

Figure 2a.

3.3.4. Evaluation Scheme

We developed an evaluation scheme to evaluate each of the experiment protocols introduced above. The evaluation scheme included HRI (human–robot interaction) criteria and collaborative assembly performance criteria related to the KPI (key performance indicator) of the collaborative assembly [

24]. The HRI criteria were categorized into pHRI (physical HRI) and cHRI (cognitive HRI) categories [

74]. The pHRI criteria were subjectively assessed by each human subject for the entire assembly task (including the handover operation) using a Likert scale between 1 and 5 as shown in

Figure 5, where score 5 indicated very high and score 1 indicated extremely low pHRI. We determined a set of pHRI criteria as explained in

Table 5. We expressed cHRI in two criteria: (i) human subject’s trust in the robot, and (ii) human subject’s cognitive workload while collaborating with the robot for the collaborative assembly task, including the handover operation [

42,

46]. We used the same Likert scale as shown in

Figure 5 to assess human trust. We followed the paper-based NASA TLX [

75] for assessing the cognitive workload of the subjects while collaborating with the robot for the task.

We expressed the assembly performance in several criteria as follows: (i) Handover success rate (

) was computed using the formula expressed in Equation (4), where

stands for the number of failed handover trials and

stands for the total number of handover trials. (ii) Safety in the handover (

) was computed using the formula expressed in Equation (5), where

stands for the number of handover trials when human subjects experienced impulse forces, and

stands for the total number of handover trials. (iii) Handover efficiency (

) was computed using the formula expressed in Equation (6), where

stands for the mean targeted or standard time and

stands for the mean recorded time for a handover trial. (iv) Assembly efficiency (

) was computed using the formula expressed in Equation (7), where

stands for the mean targeted or standard time for an assembly trial including handover and

stands for the mean recorded time for an assembly trial including handover. All criteria were evaluated through the experiment for each subject separately.

In addition to the HRI criteria and assembly performance criteria, we measured the human and robot kinematics data for each assembly trial. An encoder-type position sensor was attached to the gripper of the robot manipulator to measure the absolute velocity of the robot arm’s last link (end effector) in each trial. A foil strain gauge-type force sensor was attached inside the robot end effector (gripper) to measure the grip force of the robot arm’s last link (end effector) in each trial.

3.3.5. Experimental Results and Analyses

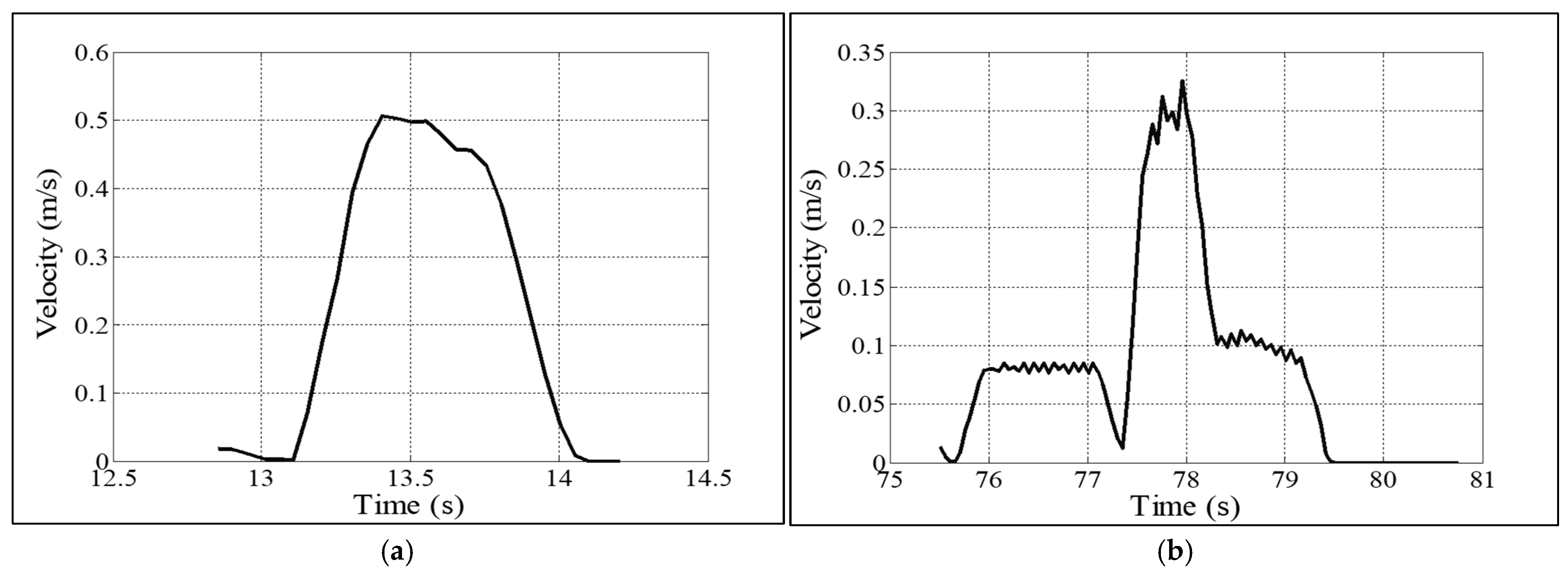

We compared the absolute velocities of the robot’s last link (end effector) during the handover at high trust, medium trust, and low trust of the robot in the human.

Figure 6 shows sample absolute velocity profiles of the robot arm’s last link (end effector) for the robot’s high-trust and low-trust situations.

Table 6 compares the mean values of the robot arm’s end effector’s absolute velocities for different computed robot trust levels in the human. The results show that the robot used modified (braced type) handover configurations with reduced absolute velocities when the robot had medium and low trust in the human [

42]. The reason might be that the robot needed to be more cautious in its handover motion planning when it realized that its trust in the human became medium to low.

Table 6 also compares the mean values of the robot arm’s end effector’s grip forces for different computed robot trust levels in humans. The results show that the robot used modified (braced type) handover configurations with higher grip forces when the robot had medium and low trust in the humans. The reason might be that the robot needed to be more cautious to secure the object (payload) when it realized that its trust in humans became medium to low [

42].

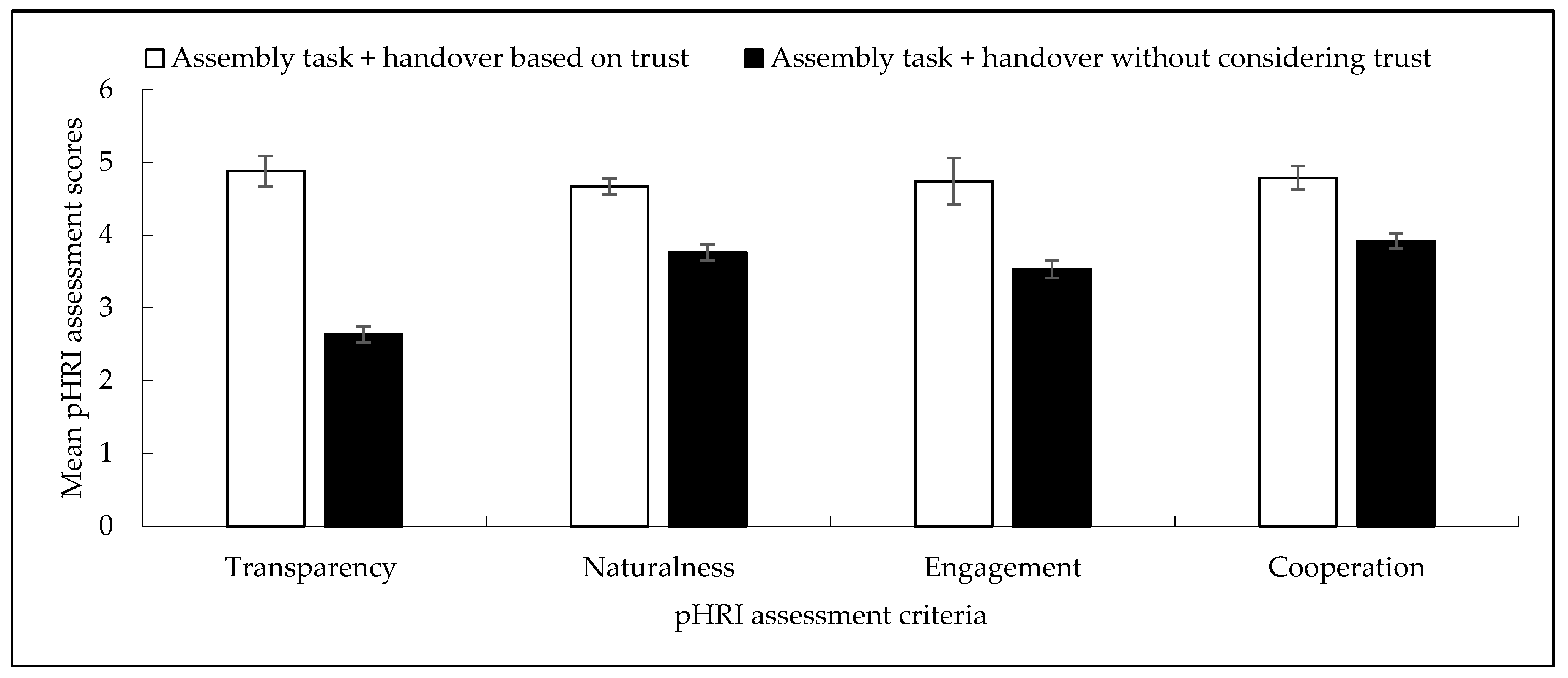

Figure 7 compares the pHRI perceived by human subjects between two different experimental conditions: assembly task plus handover based on trust (“trust-based handover”) and assembly task plus handover without considering trust (“traditional handover”). The comparison results showed that the pHRI results for the trust-based handover were significantly better than those for the traditional handover. It is believed that the real-time display of trust and trust levels served as warning messages to the human collaborators and made the contextual information transparent to them. The change in robot handover configurations based on its trust in humans also acted as a high-class communication approach by the robot manipulator to convey the prevailing trust situations and potential consequences due to trust status to the humans [

76], which might enhance transparency in the human–robot collaborative assembly and handover task. It is also believed that the prevailing transparency and the “cautious (slow)” handover configurations and kinematic strategies helped the human feel natural, which might enhance naturalness in the collaborative task perceived by the human co-workers. On the other hand, the real-time trust display (higher transparency) and adjustments in handover configurations helped the humans mentally and physically connect and attune with the robot manipulator, which might enhance the engagement level of the human with the robot [

77]. We may also argue that the highly transparent, natural, and engaged collaboration between the human and the robot during the collaborative task resulted in the perception of more intense cooperation between the human and the robot for the trust-based handover condition over the traditional handover condition. Those were the most probable reasons behind the comparatively better perceived pHRI for the trust-based handover condition [

42].

We conducted analysis of variances (ANOVAs) on each pHRI criterion (transparency, naturalness, engagement, cooperation, team fluency) separately. ANOVA results showed that variations in pHRI assessment results due to consideration of robot trust in robot handover configuration and kinematic adjustment were statistically significant (

for each pHRI criterion, e.g., for transparency,

), which indicated that consideration of robot trust produced significantly differential effects on pHRI perceived by the subjects. On the other hand, variations between the subjects who participated in the study were not statistically significant (

for each pHRI criterion, e.g., for transparency,

), which indicated that the results could be considered as the general results even though a comparatively small number of human subjects participated in the study [

46].

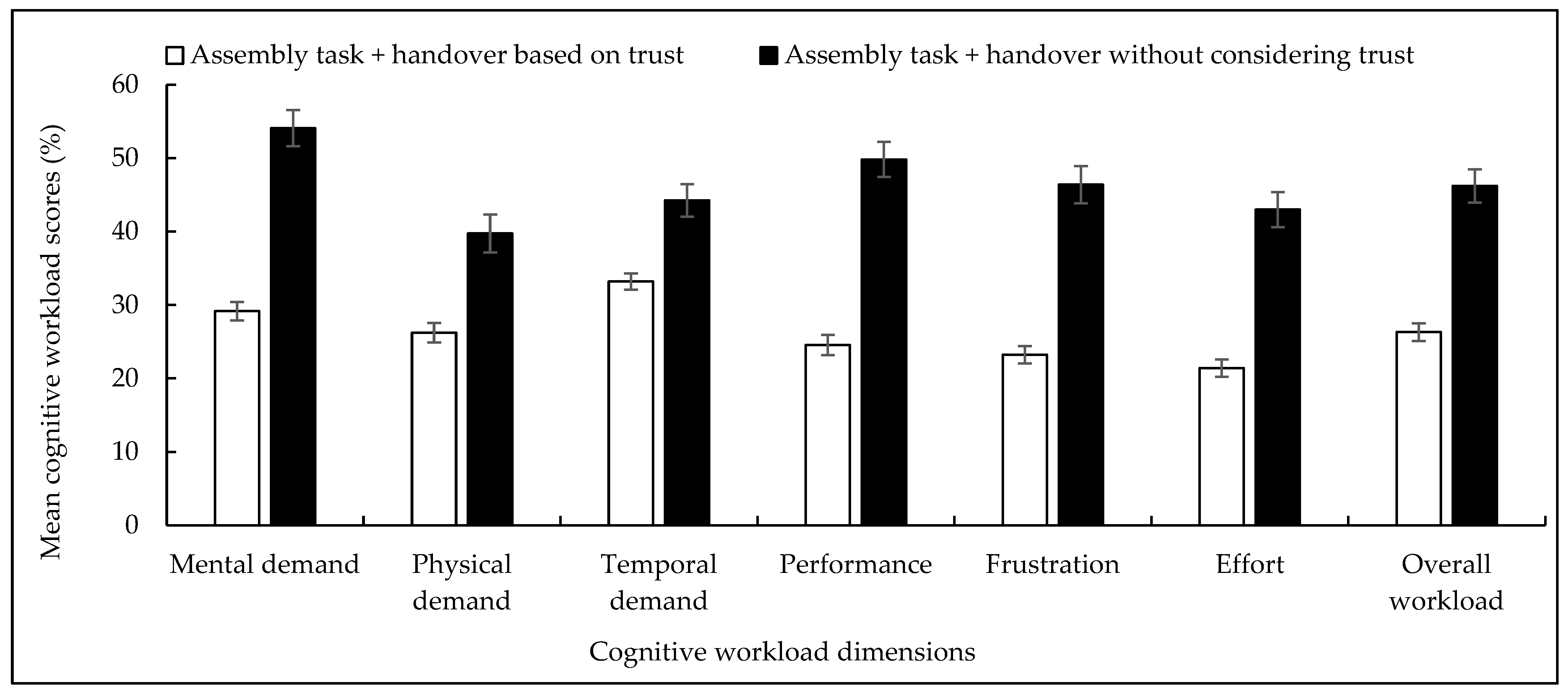

As we compared the cHRI assessment results,

Table 7 shows a 43.09% reduction in the mean cognitive workload and a 27.70% increment in human trust (subjectively assessed) in the robot for the trust-based handover condition compared to the traditional handover condition. It is believed that the advantages in the pHRI results (especially the prevailing transparency in the performance and fault status of the human co-workers expressed through the computed trust values displayed on the screen) might reduce the cognitive workloads of humans.

Figure 8 shows the comparison of the overall cognitive workloads between the two handover conditions. The figure also compares in detail the assessment results for each of the six dimensions of the NASA TLX between the trust-based and traditional handover conditions. We conducted ANOVAs on each of the cHRI criteria (workload and human trust) separately. ANOVA results showed that variations in the cHRI assessment results were statistically significant (

for each criterion, e.g., for cognitive workload,

). The results showed the significance of the effects of consideration of robot trust in the handover design on cHRI assessment results for the human co-workers. For the ANOVA results, variations between the human subjects were not statistically significant (

at each criterion, e.g., for cognitive workload,

). ANOVA results proved the generality of the cHRI results even though a comparatively small number of human subjects participated in the study [

24].

The results in

Table 8 show 30%, 30%, and 7.82% improvement in handover safety, overall handover success rate, and overall assembly efficiency, respectively, for the trust-based handover condition over the traditional handover condition.

Table 9 compares the mean impulse (collision) forces between trust-based and traditional handover conditions. It is believed that the “cautious (slow)” handover kinematics (motion) and “braced-like” handover configurations of the robot’s end effector for comparatively low robot trust situations (medium and low trust situations) might reduce potential collisions and impulse forces during the handover operation. It is also believed that the reduction in the potential collisions and impulse forces might improve the safety for the trust-based handover over the traditional handover [

46]. It also seemed to be rational that enhanced safety and pHRI might improve the overall handover success rate for the trust-based handover condition over the traditional handover condition [

78].

We see that the results in

Table 8 show 0.90% less handover efficiency for the trust-based handover condition compared to the traditional handover condition. It is assumed that it might happen due to the requirement of larger handover time for the cautious (slower) handover motions that we set for different cautious handover strategies demonstrated in

Figure 2b,c for the low trust situations. However, the mean overall assembly efficiency involving the trust-based handover operation was clearly higher than the mean overall assembly efficiency involving the traditional handover operation, as we can see in

Table 8. This phenomenon can be explained by considering the overall performance of the human–robot collaborative task. It is believed that the “cautious” handover motions for low trust situations reduced the handover efficiency a little bit due to the reduced absolute speeds we set for low trust conditions, as demonstrated in

Figure 2b,c. However, the advantages gained in pHRI, cognitive workload, and safety made up the loss of efficiency reduction due to the “cautious” handover operations and thus helped increase the overall efficiency of the entire assembly task involving the trust-based handover condition [

42].

Moreover, the handover operations followed the “cautious” motions only when the robot’s trust in humans was low. It is believed that trust display and trust-based warning messages (

Figure 3), superior pHRI, and reduced cognitive workload enhanced human performance and reduced human faults in the collaborative task, which helped maintain a high

. Consequently, the robot in most cases followed the default handover trajectory (

Figure 2a) as reflected in the results presented in

Table 9. The results in

Table 9 show that the robot did not need to follow the cautious handover motions in 80% of the assembly trials. The table also shows that the robot followed the medium cautious handover trajectory (

Figure 2b) in 15% assembly trials, and the very cautious handover trajectory in only 5% assembly trials. As the results show, the prevailing high-trust situations did not necessitate cautious handover trajectories in most trials. As cautious handover motions occurred in only 20% of the trials, it did not adversely affect the overall assembly efficiency too much, and thus, the overall assembly efficiency got a chance to increase. The results also showed that the measurement and display of

in conjunction with the handover operation played a significant role in increasing robot trust in humans (

Table 7). The results shown in

Table 7 revealed that improvements in HRI, safety, and assembly efficiency for the assembly task involving trust-based handover operation enhanced human trust in the robot as well.

Table 10 compares the mean impulse (collision) forces between trust-based and traditional handover conditions. The results showed that the impulse (collision) forces for the trust-based handover condition were almost zero, though there were impulse (collision) forces for the traditional handover condition. Those results clearly showed the superiority of the trust-based handover operation over the traditional handover operation in the collaborative assembly task [

42,

46].