Artificial Intelligence in Organoid-Based Disease Modeling: A New Frontier in Precision Medicine

Abstract

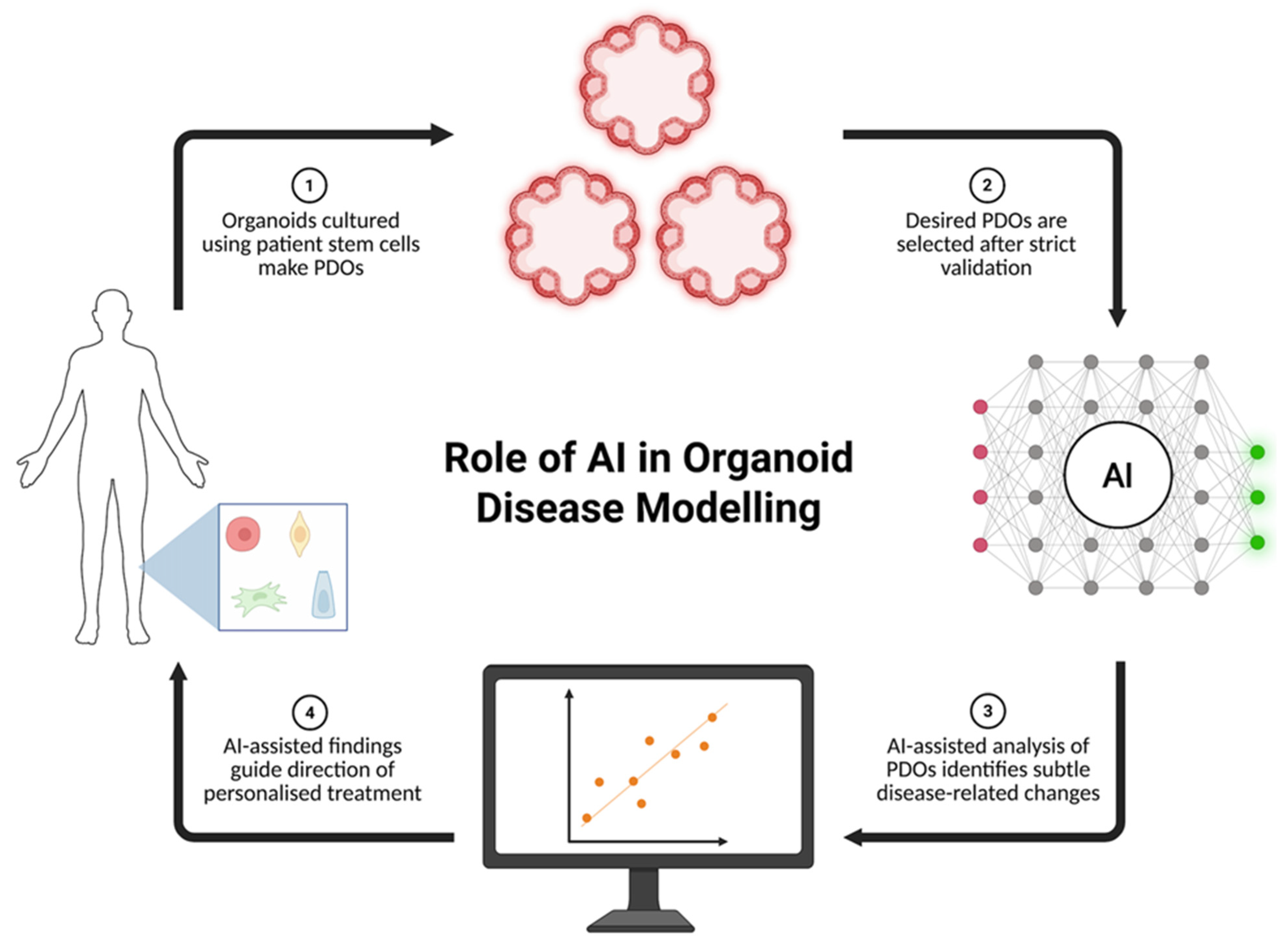

1. Introduction

2. Organoids as Disease Models

3. AI Methodologies for Organoid Analysis

3.1. High-Content Image Analysis (Segmentation, Profiling, Screening)

3.2. Spatio-Temporal Modeling of Organoid Development

3.3. Omics Data Integration Using Machine Learning

3.4. Drug Screening and Personalized Medicine Applications

3.5. Organoid Quality Control and Standardization

3.6. Organoid-on-Chip Systems and Organoid Intelligence

4. AI Applications in Disease-Specific Organoid Model

5. Challenges and Limitations

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sato, T.; Vries, R.G.; Snippert, H.J.; Van De Wetering, M.; Barker, N.; Stange, D.E.; Van Es, J.H.; Abo, A.; Kujala, P.; Peters, P.J.; et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 2009, 459, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Renner, M.; Martin, C.A.; Wenzel, D.; Bicknell, L.S.; Hurles, M.E.; Homfray, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Jackson, A.P.; Knoblich, J.A. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 2013, 501, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Organogenesisin a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 2014, 345, 1247125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huch, M.; Gehart, H.; Van Boxtel, R.; Hamer, K.; Blokzijl, F.; Verstegen, M.M.A.; Ellis, E.; van Wenum, M.; Fuchs, S.A.; de Ligt, J.; et al. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell 2015, 160, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorel, L.; Perréard, M.; Florent, R.; Divoux, J.; Coffy, S.; Vincent, A.; Gaggioli, C.; Guasch, G.; Gidrol, X.; Weiswald, L.-B.; et al. Patient-derived tumor organoids: A new avenue for preclinical research and precision medicine in oncology. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandino, G.; Satchi-Fainaro, R.; Tinhofer, I.; Tonon, G.; Heilshorn, S.C.; Kwon, Y.J.; Ciliberto, G. Cancer Organoids as reliable disease models to drive clinical development of novel therapies. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Li, P.; Du, F.; Shang, L.; Li, L. The role of organoids in cancer research. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Xu, H.; Zeng, K.; Ye, M.; Pei, R.; Wang, K. Advances in liver organoids: Replicating hepatic complexity for toxicity assessment and disease modeling. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, R.; Koike, H. Modeling human liver organ development and diseases with pluripotent stem cell-derived organoids. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1133534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.O.; Rodriguez-Romera, A.; Reyat, J.S.; Olijnik, A.A.; Colombo, M.; Wang, G.; Wen, W.X.; Sousos, N.; Murphy, L.C.; Grygielska, B.; et al. Human Bone Marrow Organoids for Disease Modeling, Discovery, and Validation of Therapeutic Targets in Hematologic Malignancies. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 364–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, M.C. Inducing definitive hematopoiesis in a dish. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Lanzon, M.; Kroemer, G.; Maiuri, M.C. Organoids for Modeling Genetic Diseases. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 337, 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi, T.; Hiratsuka, K.; Saiz, E.G.; Morizane, R. Kidney organoids in translational medicine: Disease modeling and regenerative medicine. Dev. Dyn. 2020, 249, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gong, B. Human Organoids and Their Application in Tumor Models, Disease Modeling, and Tissue Engineering. Med. Bull. 2025, 1, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.J.; Murray, G.I.; McLean, M.H. Current concepts in tumour-derived organoids. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhare, R.; Gandhi, K.A.; Kadam, A.; Raja, A.; Singh, A.; Madhav, M.; Chaubal, R.; Pandey, S.; Gupta, S. Integration of Organoids with CRISPR Screens: A Narrative Review. Biol. Cell 2025, 117, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xiang, Y.; Gan, S.; Wu, L.; Yan, J.; Ye, D.; Zhang, J. Application of artificial intelligence in medical imaging for tumor diagnosis and treatment: A comprehensive approach. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckchash, H.; Verma, G.K.; Prasad, D.K. Applications and Challenges of AI and Microscopy in Life Science Research: A Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13135. arXiv:2501.13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cen, X.; Yi, C.; Wang, F.A.; Ding, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y. Challenges in AI-driven Biomedical Multimodal Data Fusion and Analysis. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2025, 23, qzaf011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, M.; Dallio, M.; Napolitano, C.; Basile, C.; Di Nardo, F.; Vaia, P.; Iodice, P.; Federico, A. Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Human Cancer: Is It Time to Update the Diagnostic and Predictive Models in Managing Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)? Diagnostics 2025, 15, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.D.; Sartorelli, V. A deep learning adversarial autoencoder with dynamic batching displays high performance in denoising and ordering scRNA-seq data. iScience 2024, 27, 109027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdiratta, G.; Duda, J.T.; Elahi, A.; Borthakur, A.; Chatterjee, N.; Gee, J.; Sagreiya, H.; Witschey, W.R.T.; Kahn, C.E. Automated Integration of AI Results into Radiology Reports Using Common Data Elements. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2025, 38, 2623–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.M.I.; Mohanraj, J. Revolutionizing diabetic retinopathy screening and management: The role of artificial intelligence and machine learning. World J. Clin. Cases 2025, 13, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Cai, X.; Guan, R. Recent progress on the organoids: Techniques, advantages and applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 185, 117942. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0753332225001362?via%3Dihub (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Cui, W.; Zhang, B.; Fonseca, P.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, P.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Seashore-Ludlow, B.; et al. Patient-derived organoids in precision cancer medicine. Med 2024, 5, 1351–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Huch, M. Disease modelling in human organoids. DMM Dis. Models Mech. 2019, 12, dmm039347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgasi, C.; Cucci, A.; Follenzi, A. IPSC-derived liver organoids: A journey from drug screening, to disease modeling, arriving to regenerative medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aili, Y.; Maimaitiming, N.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Brain organoids: A new tool for modelling of neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcez, P.P.; Loiola, E.C.; Da Costa, R.M.; Higa, L.M.; Trindade, P.; Delvecchio, R.; Nascimento, J.M.; Brindeiro, R.; Tanuri, A.; Rehen, S.K. Zika virus: Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids. Science 2016, 352, 816–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgine, P.E. Human bone marrow organoids: Emerging progress but persisting challenges. In Trends in Biotechnology; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, K.; Li, E.; Aydemir, I.; Liu, Y.; Han, X.; Bi, H.; Wang, P.; Tao, K.; Ji, A.; Chen, Y.-H.; et al. Development of iPSC-derived human bone marrow organoid for autonomous hematopoiesis and patient-derived HSPC engraftment. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Su, J. AI-enabled organoids: Construction, analysis, and application. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 31, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, Q.; Yang, S.; Jiang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Gu, Z. Organoids revealed: Morphological analysis of the profound next generation in-vitro model with artificial intelligence. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2023, 6, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; You, X.; Zhao, G. Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for human living organoid research. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 42, 140–164. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452199X24003657 (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Branciforti, F.; Salvi, M.; D’Agostino, F.; Marzola, F.; Cornacchia, S.; De Titta, M.O.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Meloni, I.; Moschetta, M.; Porciani, N.; et al. Segmentation and Multi-Timepoint Tracking of 3D Cancer Organoids from Optical Coherence Tomography Images Using Deep Neural Networks. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Chen, J.; He, G.; Peng, Q. Artificial intelligence in high-dose-rate brachytherapy treatment planning for cervical cancer: A review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1507592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, H.; Tabibzadeh, N.; Morizane, R. Advancing preclinical drug evaluation through automated 3D imaging for high-throughput screening with kidney organoids. Biofabrication 2024, 16, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampart, F.L.; Iber, D.; Doumpas, N. Organoids in high-throughput and high-content screenings. Front. Chem. Eng. 2023, 5, 1120348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, S.; Yu, P.; Li, L.; Guo, C.; Li, R. A novel deep learning segmentation model for organoid-based drug screening. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1080273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Singh, B.; Ethakota, J.; John Ogedegbe, O.; Lanny Ntukidem, O.; Chitkara, A.; Malik, D.B. The role of artificial intelligence in colorectal cancer and polyp detection: A sys-tematic review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.; Edwards, L.; Singh, R. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Colorectal Cancer Screening: Lesion Detection and Lesion Characterization. Cancers 2023, 15, 5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Li, G.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z.; Cheung, M.; Luo, X. A deep learning model for detection and tracking in high-throughput images of organoid. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 134, 104490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, L.; Jung-Klawitter, S.; Mikut, R.; Richter, P.; Fischer, M.; Karimian-Jazi, K.; Breckwoldt, M.O.; Bendszus, M.; Heiland, S.; Kleesiek, J.; et al. An AI-based segmentation and analysis pipeline for high-field MR monitoring of cerebral organoids. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scipioni, L.; Tedeschi, G.; Atwood, S.; Digman, M.A.; Gratton, E. Spatiotemporal single-cell phenotyping in living 3D skin organoids. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 129a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Betjes, M.A.; Ender, P.; Goos, Y.J.; Huelsz-Prince, G.; Clevers, H.; van Zon, J.S.; Tans, S.J. Organoid cell fate dynamics in space and time. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Betjes, M.A.; Goos, Y.J.; Huelsz-Prince, G.; Clevers, H.; van Zon, J.S.; Tans, S.J. Following cell type transitions in space and time by combining live-cell tracking and endpoint cell identity in intestinal organoids. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelori, B.; Bardella, G.; Spinelli, I.; Ramawat, S.; Pani, P.; Ferraina, S.; Scardapane, S. Spatio-temporal transformers for decoding neural movement control. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 016023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maramraju, S.; Kowalczewski, A.; Kaza, A.; Liu, X.; Singaraju, J.P.; Albert, M.V.; Ma, Z.; Yang, H. AI-organoid integrated systems for biomedical studies and applications. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2024, 9, e10641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballav, S.; Ranjan, A.; Sur, S.; Basu, S. Organoid Intelligence: Bridging Artificial Intelligence for Biological Computing and Neurological Insights. In Technologies in Cell Culture: A Journey From Basics to Advanced Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Zambare, W.; Huang, H.; Wu, C.; Yoder, S.; Gao, Y.; Kim, J.; Romesser, P.B. Leveraging a Patient-Derived Tumoroid Platform for Precision Radiotherapy: Uncovering DNA Damage Repair Inhibitor-Mediated Radiosensitization and Therapeutic Resistance in Rectal Cancer. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassé, M.; El Saghir, J.; Berthier, C.C.; Eddy, S.; Fischer, M.; Laufer, S.D.; Kylies, D.; Hutzfeldt, A.; Bonin, L.L.; Dumoulin, B.; et al. An integrated organoid omics map extends modeling potential of kidney disease. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Ma, M.; Sun, P.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X. Multi-omics perspective: Mechanisms of gastrointestinal injury repair. Burn. Trauma. 2025, 13, tkae057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldner-Busztin, D.; Nisantzis, P.F.; Edmunds, S.J.; Boza, G.; Racimo, F.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Limborg, M.T.; Lahti, L.; de Polavieja, G.G. Dealing with dimensionality: The application of machine learning to multi-omics data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Shen, L.; Long, Q. Deep learning-based approaches for multi-omics data integration and analysis. BioData Min. 2024, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.R.; Hashmy, R. Artificial Intelligence-based Multiomics Integration Model for Cancer Subtyping. In Proceedings of the 2022 9th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development, New Delhi, India, 23–25 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mataraso, S.J.; Espinosa, C.A.; Seong, D.; Reincke, S.M.; Berson, E.; Reiss, J.D.; Kim, Y.; Ghanem, M.; Shu, C.-H.; James, T.; et al. A machine learning approach to leveraging electronic health records for enhanced omics analysis. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghav, S.; Suri, A.; Kumar, D.; Aakansha, A.; Rathore, M.; Roy, S. A hierarchical clustering approach for colorectal cancer molecular subtypes identification from gene expression data. Intell. Med. 2024, 4, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, K.; Huber, C.; Furst, J.D.; Raicu, D.S.; Tchoua, R. Iterative K-means clustering for disease subtype discovery. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Medical Imaging and Computer-Aided Diagnosis (MICAD 2023), Cambridge, UK, 9–10 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Ruhel, R.; van Wijnen, A.J. Unlocking biological complexity: The role of machine learning in integrative multi-omics. Acad. Biol. 2024, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahan, P.; Cacchiarelli, D.; Dunn, S.J.; Hemberg, M.; de Sousa Lopes, S.M.C.; Morris, S.A.; Rackham, O.J.; del Sol, A.; Wells, C.A. Computational Stem Cell Biology: Open Questions and Guiding Principles. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.; Jamal, T.; Ali, A.; Parthasarathi, R. Multiscale computational and machine learning models for designing stem cell-based regenerative medicine therapies. In Computational Biology for Stem Cell Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Obreque, J.; Vergara-Gómez, L.; Venegas, N.; Weber, H.; Owen, G.I.; Pérez-Moreno, P.; Leal, P.; Roa, J.C.; Bizama, C. Advances towards the use of gastrointestinal tumor patient-derived organoids as a therapeutic decision-making tool. Biol. Res. 2023, 56, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittner, M.I.; Farajnia, S. AI in drug discovery: Applications, opportunities, and challenges. Patterns 2022, 3, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Byrne, R.; Schneider, G.; Yang, S. Concepts of Artificial Intelligence for Computer-Assisted Drug Discovery. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10520–10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Blair Richardson, A.; Rosati, R.; Rajewski, A.; Diaz, R.; Appleyard, L.; Pereira, S.; Bernard, B.; Javle, M.M.; King, G.T.; et al. Association between ex vivo pharmacotyping of patient-derived tumor organoids and personalized therapeutic options for patients with biliary tract cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapcsak, S.; Qiao, Y.; Huang, X.; Sera, T.D.; Bailey, M.H.; Welm, B.E.; Welm, A.L.; Marth, G.T. Abstract 2723: Model-based cancer therapy selection by linking tumor vulnerabilities to drug mechanism. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.T.; Huang, P.H. Exploiting vulnerabilities in cancer signalling networks to combat targeted therapy resistance. Essays Biochem. 2018, 62, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, M.; Gaggianesi, M.; D’Accardo, C.; Porcelli, G.; Turdo, A.; Di Marco, C.; Patella, B.; Di Franco, S.; Modica, C.; Di Bella, S.; et al. A Novel Tumor on Chip Mimicking the Breast Cancer Microenvironment for Dynamic Drug Screening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Wright, J.A.; Worthley, D.L.; Murphy, E.; Woods, S.L. Precision Medicine for Peritoneal Carcinomatosis—Current Advances in Organoid Drug Testing and Clinical Applicability. Organoids 2025, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehling, K.; Parekh, S.; Schneider, F.; Kirchner, M.; Kondylis, V.; Nikopoulou, C.; Tessarz, P. RNA-sequencing of single cholangiocyte-derived organoids reveals high organoid-to organoid variability. Life Sci. Alliance 2022, 5, e202101340. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Sun, H.; Hou, X.; Sun, J.; Tang, M.; Zhang, Y.B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, C. Standard operating procedure combined with comprehensive quality control system for multiple LC-MS platforms urinary proteomics. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Kowalczewski, A.; Vu, D.; Liu, X.; Salekin, A.; Yang, H.; Ma, Z. Organoid intelligence: Integration of organoid technology and artificial intelligence in the new era of in vitro models. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2024, 21, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Yu, Y. Living biobank: Standardization of organoid construction and challenges. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 3050–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.J.; Lee, S.; Kwon, D.; Oh, S.; Park, C.; Jeon, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, T.S.; Oh, I.U. Essential Guidelines for Manufacturing and Application of Organoids. Int. J. Stem Cells 2024, 17, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhito, I.R.; Kim, T.H. Recent advances and challenges in organoid-on-a-chip technology. Organoid 2022, 2, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, Z.; Li, C.; Zeng, X.; Tuan, R.S.; Li, Z.A. When artificial intelligence (AI) meets organoids and organs-on-chips (OoCs): Game-changer for drug discovery and development? Innov. Life 2025, 3, 100115-1–100115-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Marucci, L.; Homer, M.E. In silico modelling of organ-on-a-chip devices: An overview. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1520795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnova, L.; Caffo, B.S.; Gracias, D.H.; Huang, Q.; Morales Pantoja, I.E.; Tang, B.; Zack, D.J.; Berlinicke, C.A.; Boyd, J.L.; Harris, T.D.; et al. Organoid intelligence (OI): The new frontier in biocomputing and intelligence-in-a-dish. Front. Sci. 2023, 1, 1017235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T.; Morales Pantoja, I.E.; Smirnova, L. Brain organoids and organoid intelligence from ethical, legal, and social points of view. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1307613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawai, T.; Koike, M.; Kataoka, M. Human brain organoid research: An analysis of public attitudes and ethical concerns in Japan. Mol. Psychol. Brain Behav. Soc. 2025, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, T.; Aina, K.; Maass, C.; Cipriano, M.; Lambrecht, J.; Tacke, F.; Mosig, A.; Loskill, P. Studying metabolism with multi-organ chips: New tools for disease modelling, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Open Biol. 2022, 12, 210333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G.; Jordan, M.; Ilono, P. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks in Medical Image Analysis: A Review. Information 2025, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, J.J.; Pereda, C.; Adhikari, A.; Haremaki, T.; Galgoczi, S.; Siggia, E.D.; Brivanlou, A.H.; Etoc, F. Deep-learning analysis of micropattern-based organoids enables high-throughput drug screening of Huntington’s disease models. Cell Rep. Methods 2022, 2, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Swaney, J.M.; Yun, D.H.; Evans, N.B.; Antonucci, J.M.; Velasco, S.; Sohn, C.H.; Arlotta, P.; Gehrke, L.; Chung, K. Multiscale 3D phenotyping of human cerebral organoids. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Choi, Y.S.; Cho, G.; Jang, S.J. The Patient-Derived Cancer Organoids: Promises and Challenges as Platforms for Cancer Discovery. Cancers 2022, 14, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, E.B.; Kim, S.; Choi, B.; Schmid, J.K.; Kaura, K.; Lenz, H.J.; Foo, J. Understanding patient-derived tumor organoid growth through an integrated imaging and mathematical modeling framework. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, L.; Xu, J.; Sotra, A.; Chaudary, A.; Gao, J.; Rajasekar, S.; Anvari, N.; Mahyar, H.; Zhang, B. D-CryptO: Deep learning-based analysis of colon organoid morphology from brightfield images. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 4118–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, K.; Takagi, M.; Hiyama, G.; Goda, K. A deep-learning model for characterizing tumor heterogeneity using patient-derived organoids. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, M.; Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Z. Image-based profiling and deep learning reveal morphological heterogeneity of colorectal cancer organoids. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 173, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.M.; Schuster, B.; Kashaf, S.S.; Liu, P.; Ben-Yishay, R.; Ishay-Ronen, D.; Izumchenko, E.; Shen, L.; Weber, C.R.; Bielski, M.; et al. OrganoID: A versatile deep learning platform for tracking and analysis of single-organoid dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Schriever, H.; Jiang, S.; Bais, A.; Wu, H.; Kostka, D.; Li, G. Computational profiling of hiPSC-derived heart organoids reveals chamber defects associated with NKX2-5 deficiency. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzel, A.S.; Hemmer, K.; Kaoma, T.; Smits, L.M.; Bolognin, S.; Lucarelli, P.; Rosety, I.; Zagare, A.; Antony, P.; Nickels, S.L.; et al. Machine learning-assisted neurotoxicity prediction in human midbrain organoids. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 75, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Hayat, H.; Liu, S.; Tull, E.; Bishop, J.O.; Dwan, B.F.; Gudi, M.; Talebloo, N.; Dizon, J.R.; Li, W.; et al. 3D in vivo Magnetic Particle Imaging of Human Stem Cell-Derived Islet Organoid Transplantation Using a Machine Learning Algorithm. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 704483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alani, M.; Jalab, H.A.; Pars, S.; Al-Mhanawi, B.; Taha, R.Z.; Wolvetang, E.J.; Shaker, M.R. Enhanced U-Net-Based Deep Learning Model for Automated Segmentation of Organoid Images. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Kim, T.K.; Han, Y.D.; Kim, K.A.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.S. Development of a deep learning based image processing tool for enhanced organoid analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.; Karimijafarbigloo, S.; Roggenbuck, D.; Rödiger, S. Applications of Neural Networks in Biomedical Data Analysis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebler, R.; Reinecke, I.; Sedlmayr, M.; Goldammer, M. Enhancing Clinical Data Infrastructure for AI Research: Comparative Evaluation of Data Management Architectures. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e74976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, B.J.; Kitchen, A.C.; Tran, N.T.; Habibollahi, F.; Khajehnejad, M.; Parker, B.J.; Bhat, A.; Rollo, B.; Razi, A.; Friston, K.J. In vitro neurons learn and exhibit sentience when embodied in a simulated game-world. Neuron 2022, 110, 3952–3969.e8. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896627322008066 (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wadan, A.H.S. Organoid intelligence and biocomputing advances: Current steps and future directions. Brain Organoid Syst. Neurosci. J. 2025, 3, 8–14. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S294992162500002X#bib2 (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T.; Smirnova, L.; Morales Pantoja, I.E.; Akwaboah, A.; Alam El Din, D.M.; Berlinicke, C.A.; Boyd, J.L.; Caffo, B.S.; Cappiello, B.; Cohen-Karni, T.; et al. The Baltimore declaration toward the exploration of organoid intelligence. Front. Sci. 2023, 1, 1068159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajueiro, D.O.; Celestino, V.R.R. A comprehensive review of Artificial Intelligence regulation: Weighing ethical principles and innovation. J. Econ. Technol. 2026, 4, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshjou, R.; Vodrahalli, K.; Novoa, R.A.; Jenkins, M.; Liang, W.; Rotemberg, V.; Chiou, A.S. Disparities in dermatology AI performance on a diverse, curated clinical image set. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, D.B.; Hosseini, M. The ethics of using artificial intelligence in scientific research: New guidance needed for a new tool. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 1499–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutgens, F.; Clevers, H. Human Organoids: Tools for Understanding Biology and Treating Diseases. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2020, 15, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, G.; Hedayat, S.; Vatsiou, A.; Jamin, Y.; Fernández-Mateos, J.; Khan, K.; Lampis, A.; Eason, K.; Huntingford, I.; Burke, R.; et al. Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science 2018, 359, 920–926. Available online: https://www.science.org (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corral-Acero, J.; Margara, F.; Marciniak, M.; Rodero, C.; Loncaric, F.; Feng, Y.; Lamata, P. The “Digital Twin” to enable the vision of precision cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 4556–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, M.; Allegri, L.; Caldarelli, G.; d’Andrea, V.; Di Camillo, B.; Rocha, L.M.; Rozum, J.; Sbarbati, R.; Zambelli, F. Challenges and opportunities for digital twins in precision medicine from a complex systems perspective. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, K.; Lin, E.Y.T.; Vogel, S. Global Regulatory Frameworks for the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Healthcare Services Sector. Healthcare 2024, 12, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Input Data | Organoid | Algorithm | Disease Studied | Main Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | hiPSC-Brain | Random Forest | Parkinson’s Disease | Random forest model labelled healthy and 6-OHDA brain organoids from imaging data. | Monzel et al. (2020) [93] |

| Imaging | hiPSC-Islet | K-means++ clustering | Type 1 Diabetes | Used ML to monitor islet organoids in real-time post-transplantation using magnetic particle imaging. | Sun et al. (2021) [94] |

| Imaging | PDTO-Colon | CNN | Colorectal Cancer | Growth of CRC organoids was monitored in real-time by 3D imaging data. | Gunnarsson et al. (2024) [86] |

| scRNA-seq | hiPSC-Cardiac | Random Forest | Ebstein’s Anomaly | The model identified an upregulation of genes associated with atrialisation in ventricle-lineage organoids. | Feng et al. (2022) [91] |

| Imaging | PDTO-Lung | CNN | Lung Cancer | The CNN model mapped morphological data to RNA-seq data and managed to predict the drivers of tumor heterogeneities. | Takagi et al. (2024) [88] |

| Imaging | hiPSC-Brain | CNN | Zika Virus | The SCOUT pipeline applies a CNN to high-resolution images to analyse genetic and cytoarchitectural data of brain organoids. | Albanese et al. (2020) [84] |

| Imaging | hESC-Neural | CNN | Huntington’s Disease | The CNN classified healthy and diseased neural organoids with high accuracy and was used as a drug screening tool. | Metzger et al. (2022) [83] |

| Imaging | PDTO-Colon | CNN (and others) | Colorectal Cancer | The model was used for image classification of different colorectal cancer morphologies. | Abdul et al. (2022) [87] |

| Imaging | PDTO-Colon | CNN | Colorectal Cancer | The model classified cystic and solid morphologies, and predicted apoptosis using fluorescent imaging. | Huang et al. (2024) [89] |

| Imaging | Murine-Breast | CNN | Breast Cancer | Used CNN models to track breast cancer organoid development for 13 days. | Branciforti et al. (2024) [35] |

| Imaging | PDTO-Pancreas | CNN | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | The CNN model, termed OrganoID, labels and tracks single organoids with high precision. | Matthews et al. (2022) [90] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balkhair, O.; Albalushi, H. Artificial Intelligence in Organoid-Based Disease Modeling: A New Frontier in Precision Medicine. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120845

Balkhair O, Albalushi H. Artificial Intelligence in Organoid-Based Disease Modeling: A New Frontier in Precision Medicine. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(12):845. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120845

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalkhair, Omar, and Halima Albalushi. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence in Organoid-Based Disease Modeling: A New Frontier in Precision Medicine" Biomimetics 10, no. 12: 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120845

APA StyleBalkhair, O., & Albalushi, H. (2025). Artificial Intelligence in Organoid-Based Disease Modeling: A New Frontier in Precision Medicine. Biomimetics, 10(12), 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120845