A Perspective on Bio-Inspired Approaches as Sustainable Proxy Towards an Accelerated Net Zero Emission Energy Transition

Abstract

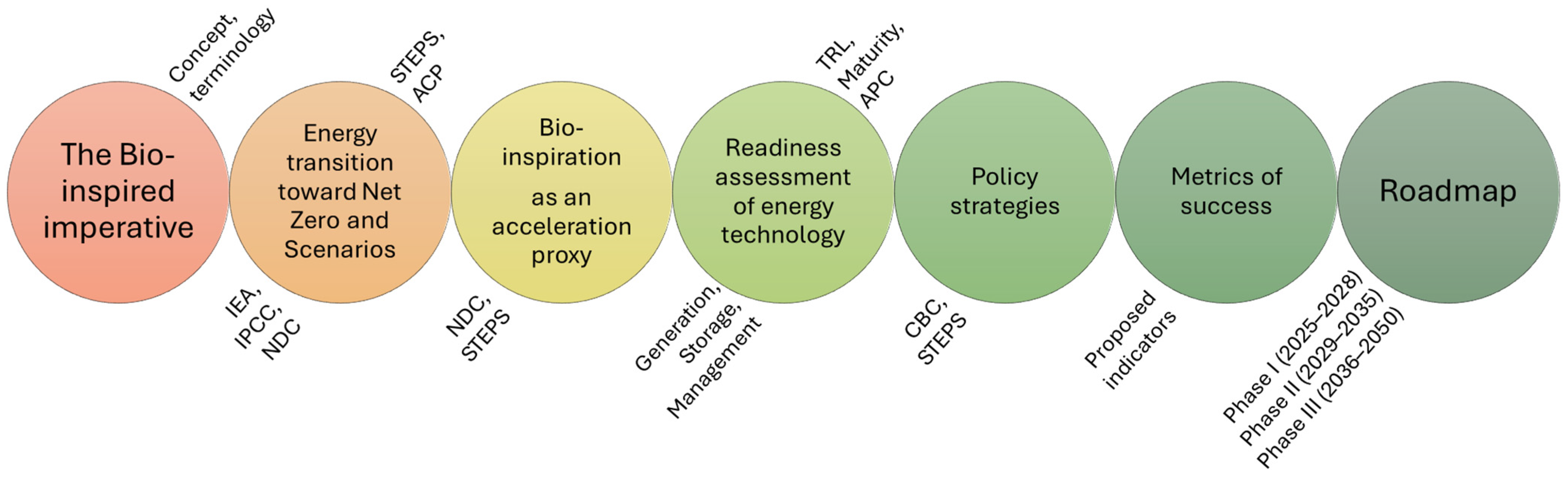

1. Introduction

- i.

- Synthesizing bio-inspired energy solutions across generation, storage, and management domains.

- ii.

- Introducing a reproducible codebook for classifying biomimetic approaches.

- iii.

- Evaluating their readiness using TRL and validation criteria.

- iv.

- Connecting biological principles to socio-technical CBCs.

- v.

- Outlining a coherent, policy-oriented roadmap for how biomimicry can contribute to achieving national net zero pledges under an APC-aligned pathway.

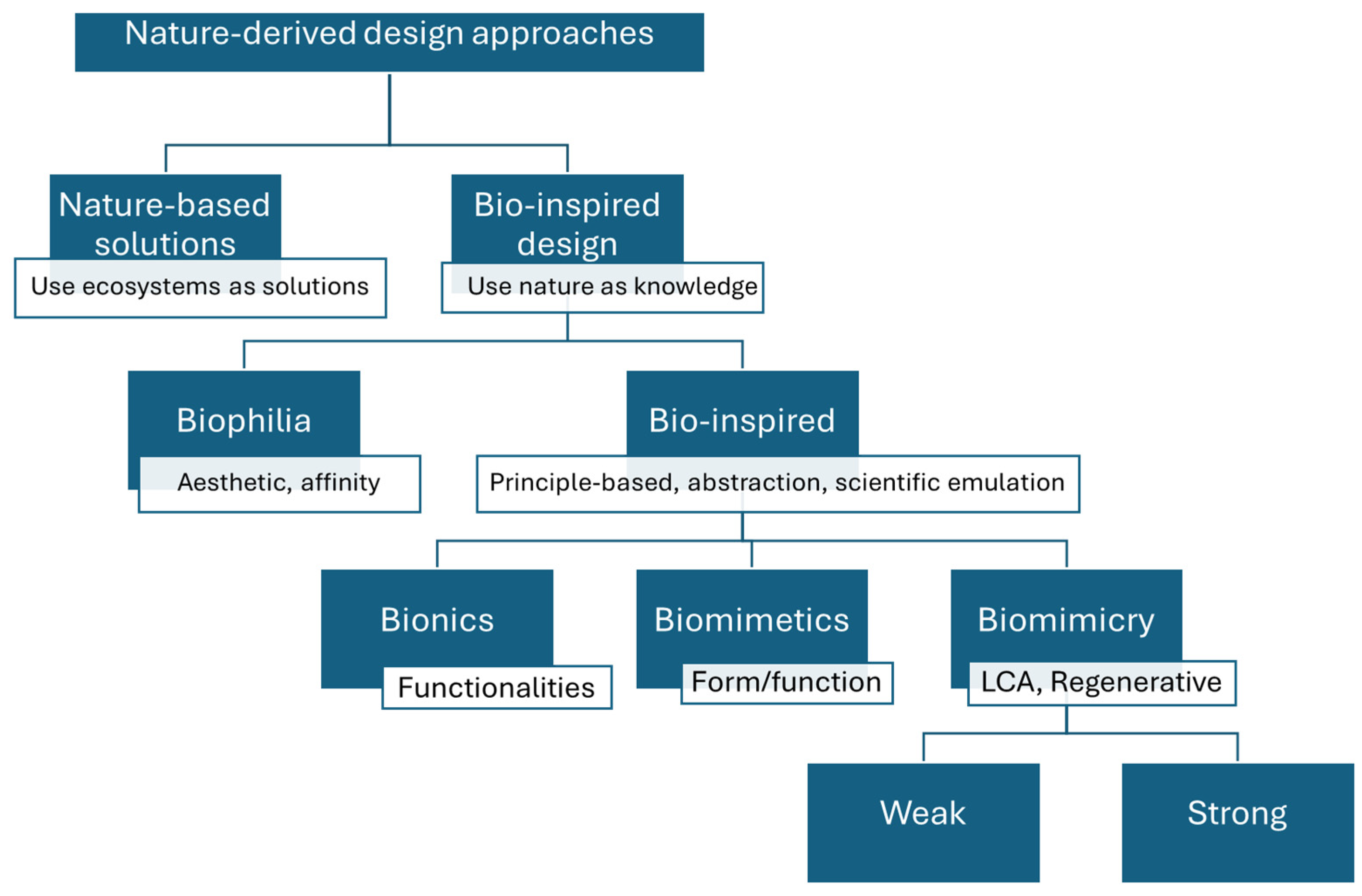

2. The Bio-Inspired Imperative

- The biological functionality is successfully transferred (biomimetics) using conventional manufacturing processes (with high pressure and high temperature), and alloys with either non-local or toxic materials.

- Or the biological functionality is successfully transferred together with low-negative environmental impact manufacturing processes and local non-toxic materials, considering and leveraging its life cycle and end of life (biomimicry).

3. The Typical Need to Focus on Energy Transition to Reach Net Zero Emissions

4. Energy Transition Framed in NZE Scenarios and Actions

- Renewables reach almost 90% of total electricity generation.

- Nearly 70% of electricity generation globally from solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind.

- More than 85% of buildings are zero-carbon ready.

- More than 90% of heavy industrial production is low emissions.

- A total of around 7.6 Gt CO2 is captured.

- A total of around 0.52 Gt CO2 is from low-carbon hydrogen.

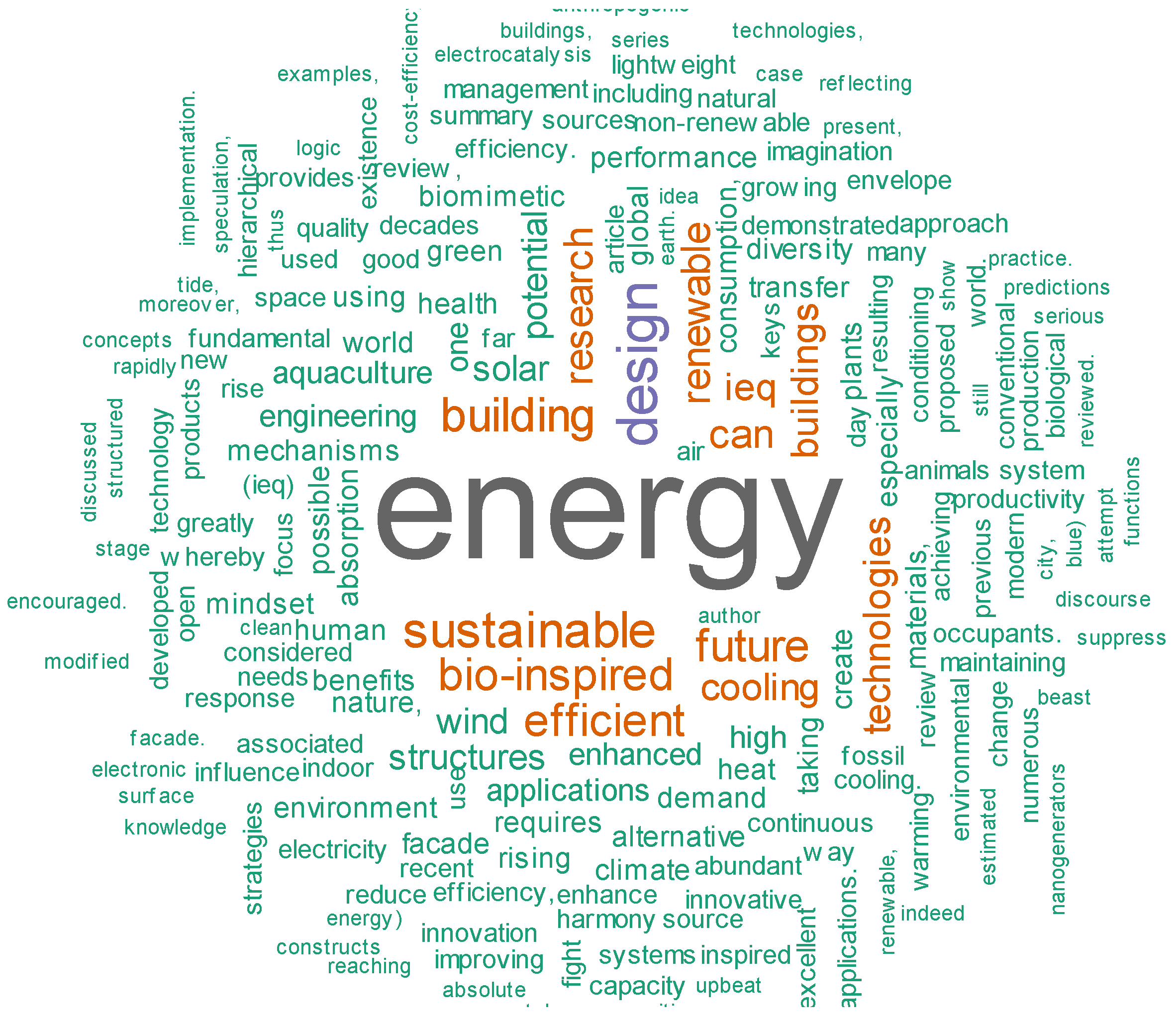

5. Bio-Inspiration as an Acceleration Proxy Towards an Integrated NZE Future

6. Readiness Assessment of Energy Technology Developments to Foster an APC Scenario Pathway

- (a)

- Technological readiness and validation context

- (b)

- Alignment with APC transformation pillars

- (c)

- Integration barriers and enabling mechanisms

- (d)

- Readiness outlook for APC implementation

7. Discussion

7.1. Policy Recommendations for Formalizing Bio-Inspired Integration in Strengthening a STEPS Pathway

7.2. A Proposed Metric of Success for Bio-Inspired Energy Solutions

7.3. Proposed Roadmap

- (a)

- Phase I (2025–2028): Deployment of Prototypes and Design of LCA

- (b)

- Phase II (2029–2035): Scaling, Evidence, and Standardization

- (c)

- Phase III (2036–2050): Consolidation and Regenerative Integration

7.4. Main Limitations

- (a)

- Limited Empirical Validation (TRL Gap):

- The core argument relies on the low TRLs (3–6) of biomimetic solutions. However, the work does not include a detailed, longitudinal analysis of successful scaling efforts to determine the specific, systemic obstacles (beyond general “policy gaps”) that have historically prevented these technologies from moving from TRL 6 to TRL 9. No patent or utility models were looked for at this stage in the research due to difficulties in assessing viable functionality and lack of theoretical description and evaluation evidence.

- The paper establishes the Maturity Gap but does not present a case study demonstrating how the proposed FPI or LCSI metrics would have accelerated a technology’s passage through the phase between R&D funding and commercialization.

- (b)

- Assessment of Economic and Social Integration:

- While the paper proposes the LCOE-B and SRC Avoided metrics, the economic models for quantifying the long-term, distributed benefits of resilience and self-healing (core biomimicry advantages) are not provided. These benefits are complex to monetize and are often seen as “externalities” by traditional investors.

- The social aspect mentioned in the introduction, is primarily addressed by the CBCs (Common Boundary Concepts) but lacks specific socio-economic indicators that can measure community acceptance, equitable access, or job creation specific to the biomimetic supply chain.

- (c)

- Policy Implementation Specificity:

7.5. Future Directions

- (a)

- Develop Standardized Quantitative Tools:

- Prioritize the development and calibration of the Life Cycle Sustainability Index (LCSI) and the Functional Performance Index (FPI). Future work should create open-source, user-friendly toolkits (e.g., a BiomiMETRIC software tool) that allow researchers and policymakers to calculate these metrics consistently, enabling true cross-technology comparison.

- Develop standardized economic models to quantify the long-term monetary benefits of SRC Avoided and MIR in large-scale energy infrastructure projects, making a clear business case for biomimicry.

- (b)

- Longitudinal Case Studies and Pilot Programs:

- Conduct in-depth longitudinal case studies on biomimetic technologies that have successfully passed TRL 7. Analyze the policy and financial mechanisms that did or could have facilitated their scaling, using the proposed FPI, MIR, and LCSI metrics in a retrospective analysis.

- Propose and execute pilot demonstration projects in collaboration with national or regional energy agencies to test the efficacy of the NbI policy classification and the new metrics (LCSI) in attracting targeted Green Bond financing.

- (c)

- Refine Policy and Governance Roadmap:

- Focus on generating explicit policy language for integrating biomimicry into global governance frameworks. This includes drafting model text for NDCs or national energy transition acts that explicitly mandate reporting on FPI and MIR for publicly funded energy projects.

- Further elaborate on the Common Boundary Concepts (CBCs) to develop a framework for stakeholder engagement that ensures the regenerative principles of biomimicry translate into tangible, positive social and ethical outcomes.

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Announced Pledges Case | APC |

| Carbon capture, usage, and storage | CCUS |

| Circular economy | CE |

| Common Boundary Concepts | CBC |

| Energy transition systems | ETS |

| Global Industry Classification Standard | GICS |

| Greenhouse gas | GHG |

| International Energy Agency | IEA |

| Life cycle assessment | LCA |

| Nature-based solutions | NBS |

| Net zero emissions | NZE |

| Nationally Determined Contributions | NDC |

| Plant-Microbial Fuel Cell | PMFC |

| Stated Policies Scenario | STEPS |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Operational Codebook

| TRL | Definition | Typical Validation Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Basic principles observed | Theoretical/concept only |

| 2 | Technology concept formulated | Analytical/early model |

| 3 | Experimental proof of concept | Lab-scale, basic validation |

| 4 | Technology validated in lab | Controlled lab testing |

| 5 | Technology validated in relevant environment | Lab + partial system integration |

| 6 | Prototype demonstrated in relevant environment | Small pilot/integrated subsystem |

| 7 | System prototype demonstration in operational environment | Field pilot |

| 8 | System complete and qualified | Real-world validation complete |

| 9 | System proven in operational use | Commercial deployment |

| Category * | Working Definition | Tagging Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Nature-inspired | Broad category where nature serves as a conceptual or aesthetic inspiration rather than a direct biological model. Does not require scientific analogy or biological fidelity. | Tag when nature influences general orientation, shape, or concept, but no specific organism/process is clearly emulated. |

| Nature-based solutions (NbS) | Actions that use (or restore) natural ecosystems to address societal challenges (climate mitigation, resilience, biodiversity, sustainable infrastructure). Based on ecosystem use, conservation, or restoration. | Tag when the intervention uses real ecosystems, vegetation, soil, water cycles, ecological restoration, or hybrid green–grey infrastructures. This is not biomimicry but a complementary category. |

| Bio-inspired | Uses biological principles as conceptual heuristics to guide engineering design, often at the abstract level (patterns, networks, distributed intelligence). | Tag when the analogy is conceptual, mathematical, or systemic (e.g., “ant colony optimization algorithm,” “mycelium-like networks”). |

| Bionics | Applies biological functions to technical systems with a strong engineering and cybernetic lens. Often mechanistic and focused on translating biological performance into devices/sensors. | Tag when biological functions are converted into mechanical, robotic, or electromechanical systems (e.g., artificial muscles, insect-wing-inspired micro-robots). |

| Biomimicry (regenerative/life cycle) | Umbrella category covering both weak and strong biomimicry. Focuses on using nature’s principles to restore, sustain, or enhance material, energy, or ecological flows. | Use when the design logic follows ecosystem behavior rather than isolated structural mimicry. |

| Biomimetics (form/function) | Engineering approach that imitates natural structures, mechanics, or geometries to improve performance, efficiency, or durability. Does not integrate system-level ecological principles. | Tag when the solution copies a form, pattern, or mechanism from nature to optimize a technical function (drag reduction, antireflection, cooling, etc.). |

| Weak biomimicry | Uses biological ideas or metaphors superficially, without achieving measurable ecological, regenerative, or systemic benefits. | Tag when sustainability effects are unverified, incidental, or symbolic, even if nature is referenced. |

| Strong biomimicry | Emulates natural processes, ecosystem dynamics, or life cycles to produce regenerative, closed-loop, or self-sustaining outcomes. | Tag when the solution shows measurable life cycle benefits, restorative effects, circularity, or ecosystem integration. |

| Pinnacle (biological analog) | The specific organism, biological structure, ecosystem, or natural process that inspires the design. Represents the natural reference model. | Always specify the pinnacle in the case description (e.g., “lotus leaf → self-cleaning PV coating”). |

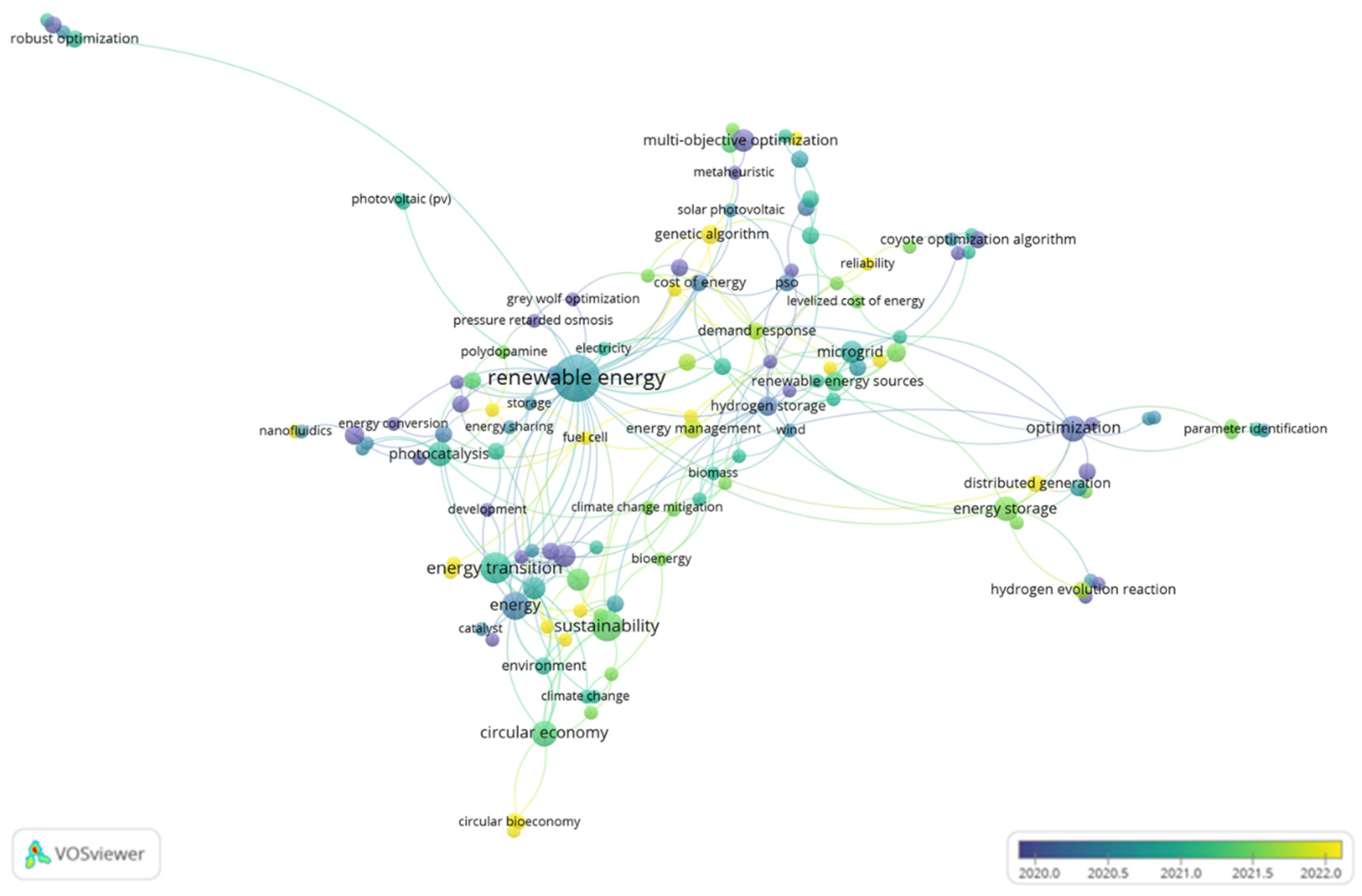

Appendix A.2. Literature Searching Protocol

- Databases: Google Scholar and ScienceDirect.

- Time window restriction: 2010–2025.

- Keyword combination query: (energy generation OR energy storage OR energy management OR optimization) AND inspired AND (nature OR biomimicry OR biomimetic) NOT architecture

- Screening: Title/abstract, then full text.

- Types of documents accepted: Gray literature and peer-reviewed documents such as books, book chapters, scientific articles, thesis, and conference papers.

- Inclusion criteria: Studies with at least one level of system validation such as simulation (not just the idea), English language, peer-reviewed, energy-relevant (generation/storage/management), and reports a mechanism, metric, or validation.

- Exclusion criteria: Non-energy applications (studies related to architecture, biophilic considerations), studies with purely metaphorical uses without mechanism, and review articles unless they contain primary metrics.

- Extraction fields: Domain, pinnacle, approach (biomimetics/biomimicry), device/system, objective metric, validation level, maturity, LCA evidence, social impact evidence, and citation.

Appendix A.3. Current Evidence on Bio-Inspired System Design for Energy Generation, Energy Storage and Energy Management

Appendix A.3.1. Key Aspects When Considering How Nature Acts in the Design of Energy Systems

| Domain | Pinnacle | Approach | Energy System/Device | Validation Level | Maturity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy generation | Central fovea (retina) | Biomimetics | Thin-film PV/light-trapping textures | Simulation/Lab | Concept–Prototype | [55] |

| Energy generation | Coleoptera beetle scales | Biomimetics | Thin-film PV/light-trapping textures | Simulation/Lab | Concept–Prototype | [55] |

| Energy generation | Pink butterfly wings | Biomimetics | Thin-film PV/light-trapping textures | Simulation/Lab | Concept–Prototype | [55] |

| Energy generation | Moth eye nanostructure | Biomimetics | PV cover/AR surface | Lab | Prototype | [56] |

| Energy generation | Lotus leaves, rice leaves and water strider legs (superhydrophobic) | Biomimetics | PV self-cleaning film | Lab | Prototype | [8] |

| Energy generation | ‘Sweat’ cooling strategy | Biomimicry | PV panel cooling gel | Lab/Small pilot | Prototype | [7] |

| Energy generation | Leaf anatomy/photosynthesis | Biomimicry | Leaf-mimic PV light-capturing layer | Lab | Prototype | [57] |

| Energy generation | Eastern hornet queen | Biomimetics | Electrical cell | Lab | Basic research | [58] |

| Energy generation | Protein nanowires (Geobacter) | Biomimicry | Ambient humidity harvester | Lab | Concept–Prototype | [59] |

| Energy generation | Bacteria | Biomimetics | Microbial Fuel Cell | Lab | Prototype | [60] |

| Energy generation | Bird feathers (movement) | Biomimetics | Kinetic façade energy harvester | Simulation | Concept | [61,62] |

| Energy generation | Owl feathers and the tubercles of humpback whale fins | Biomimetics | Solves aerodynamic noise | Lab testing | Laboratory component prototype. | [61] |

| Energy generation | Nelumbo nucifera (Sacred Lotus) | Biomimetics | Horizontal-axis wind blade | Simulation + Experiment | Prototype | [63] |

| Energy generation | Maple seed leaf | Biomimetics | Blades in vertical axis turbines | Simulations | Concept/Simulation | [64] |

| Energy generation | Fish schooling | Biomimetics | Vertical axis wind turbines array layout | Simulation/Theory | Concept | [65] |

| Energy generation | Rock crab legs | Biomimicry | Wave power turbine-generator systems | Concept/prototype | Concept | [66] |

| Energy generation | Sea fauna mix | Biomimetics | TALOS device | Theoretical application | Concept–Prototype | [67] |

| Energy generation | Leaf flutters (Palm leaf) | Biomimicry | Wind energy collectors (Artificial blades) | Wind tunnel tests | Prototype | [68] |

| Energy generation | Metamaterials (Defective state) | Biomimetics | Ocean monitoring systems (Wave energy harvester) | Simulation/Lab | Prototype | [69] |

| Energy storage | Photosynthesis (system-level emulation) | Biomimetics | PV + electrochem. H2 modules | Lab system integration | Concept–Prototype | [70] |

| Energy storage | Wood hierarchical porosity | Biomimetics | Battery components (separators etc.) | Lab | Prototype | [71] |

| Energy storage | Lignin quinones; Venus flytrap cage | Biomimetics | Graphene-reconfigured lignin cathode | Lab | Prototype | [72] |

| Energy storage | Sucrose-derived carbon | Biomimetics | Li4Ti5O12 anode modification | Lab | Prototype | [73] |

| Energy storage | Polysaccharides/ingestible design | Biomimetics | Edible battery + nanogenerator | Lab | Prototype | [74] |

| Energy storage | Plant leaf veins (Fractal dimensions) | Biomimetics | LHTES systems (Vertically aligned annular fins) | Numerical and experimental validations | Small pilot/Prototype | [75] |

| Energy storage | Conch shell (Spiral fins) | Biomimetics | Phase change capsule (Thermal energy storage) | Simulation | Concept–Prototype | [76] |

| Energy management | Ant pheromone foraging | Biomimicry | Dispatch/routing algorithms | Simulation | Concept | [77] |

| Energy management | Mold physarum network growth | Biomimicry | Network design/microgrids | Lab analog/Simulation | Concept | [77] |

| Energy management | Mold physarum network growth | Biomimicry | Transportation organization | Laboratory experiments with living physarum polycephalum plasmodium using physical analogs (oat flakes representing cities). | Analog lab model/Proof-of-Concept. | [78,79] |

| Energy management | Particle swarm optimization (PSO)/Genetic algorithm (GA) | Biomimetics | Renewable energy system optimization (University microgrid) | Theoretical application/Simulation | Concept | [80] |

Appendix A.3.2. Energy Generation

Appendix A.3.3. Energy Storage

Appendix A.3.4. Energy Management Optimization

References

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, 1st ed.; Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, F. Towards a Deeper Philosophy of Biomimicry. Organ. Environ. 2011, 24, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Gremmen, B. Ecological Innovation: Biomimicry as a New Way of Thinking and Acting Ecologically. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerola, A.; Robaey, Z.; Blok, V. What Does it Mean to Mimic Nature? A Typology for Biomimetic Design. Philos. Technol. 2023, 36, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, N.E.; Mead, T. Sustainability in the Biom. In Bionics and Sustainable Design; Palombini, F.L., Muthu, S.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombini, F.L.; Muthu, S.S. (Eds.) Bionics and Sustainable Design; Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, Y.; Wu, M.; Hong, S.; Wang, P. Photovoltaic panel cooling by atmospheric water sorption–evaporation cycle. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gu, X.; Ma, P.; Zhang, W.; Yu, D.; Chang, P.; Chen, X.; Li, D. Microstructured superhydrophobic anti-reflection films for performance improvement of photovoltaic devices. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 91, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorst, H.; van der Jagt, A.; Runhaar, H.; Raven, R. Structural conditions for the wider uptake of urban nature-based solutions—A conceptual framework. Cities 2021, 116, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi Asl, S. Re-powering the Nature-Intensive Systems: Insights From Linking Nature-Based Solutions and Energy Transition. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.C.; Zhong, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, T.W.; Chan, K.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Chao, C.Y.H. Bio-inspired cooling technologies and the applications in buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 225, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Liu, X.; Cheng, G.; Zhu, J. Solar steam generation through bio-inspired interface heating of broadband-absorbing plasmonic membranes. Appl. Energy 2017, 195, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18458:2015; Biomimetics—Terminology, Concepts and Methodology. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/62500.html (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2024. UNEP-UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Lee, H.; Birol, F. Energy Is at the Heart of the Solution to the Climate Challenge—IPCC. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/2020/07/31/energy-climatechallenge/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Bruce, B. Portfolio construction. In Student-Managed Investment Funds; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 129–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, B. The 3 Biggest Future Trends (and Challenges) in the Energy Sector. Available online: https://usnd.to/uGV8 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Motlagh, N.H.; Mohammadrezaei, M.; Hunt, J.; Zakeri, B. Internet of Things (IoT) and the Energy Sector. Energies 2020, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadis, E.; Tsatsaronis, G. Challenges in the decarbonization of the energy sector. Energy 2020, 205, 118025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D. Top 10 Issues Facing the Energy Industry. Energy Magazine. Available online: https://energydigital.com/top10/top-10-issues-facing-the-energy-industry (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Spending on Energy R&D by Governments, 2015–2021-Charts-Data & Statistics-IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/spending-on-energy-rd-by-governments-2015-2022 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Sagar, A.D.; Holdren, J.P. Assessing the global energy innovation system: Some key issues. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A. A Preview of Key Energy Challenges for the 2020s. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/andystone/2020/03/02/a-preview-of-key-energy-challenges-for-the-2020s/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Net Zero by 2050—A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector 2050. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2025 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- United Nations. All About the NDCs. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/all-about-ndcs (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Share: 2025 NDCs Synthesis Report Highlights Momentum Toward the Climate Transition and Calls for Accelerated Global Cooperation Ahead of COP30. Available online: https://cop30.br/en/news-about-cop30/2025-ndc-synthesis-report-highlights-momentum-toward-the-climate-transition-and-calls-for-accelerated-global-cooperation-ahead-of-cop30 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- 2025 NDC Synthesis Report, UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/2025-ndc-synthesis-report (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Wilson, J.O.; Rosen, D.; Nelson, B.A.; Yen, J. The effects of biological examples in idea generation. Des. Stud. 2010, 31, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, E.; Blanco, E.; Aujard, F.; Raskin, K. Has Biomimicry in Architecture Arrived in France? Diversity of Challenges and Opportunities for a Paradigm Shift. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Austin, M.; Garzola, D.; Delgado, N.; Jiménez, J.U.; Mora, D. Inspection of Biomimicry Approaches as an Alternative to Address Climate-Related Energy Building Challenges: A Framework for Application in Panama. Biomimetics 2020, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, A.; Zarzavilla, M.; Tejedor-Flores, N.; Mora, D.; Chen Austin, M. Sustainability Assessment of the Anthropogenic System in Panama City: Application of Biomimetic Strategies towards Regenerative Cities. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NDCs for Buildings: Ambitious, Investable, Actionable, and Inclusive, GlobalABC. Available online: https://globalabc.org/resources/publications/ndcs-buildings-ambitious-investable-actionable-and-inclusive (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Han, W.; Banat, F.; Taher, H.; Chia, W.Y.; Show, P.L. Biomimetic Approaches for Renewable Energy and Carbon Neutrality: Advancing Nature-Inspired Approaches for Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 6717–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimijazi, F.; Parra, E.; Barstow, B. Electrical Energy Storage with Engineered Biological Systems. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Austin, M.; Solano, T.; Tejedor-Flores, N.; Quintero, V.; Boya, C.; Mora, D. Bio-inspired Approaches for Sustainable Cities Design in Tropical Climate. Environ. Footpr. Eco-Des. Prod. Process. 2022, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarnah Kadri, L. Towards the LIVING Envelope: Biomimetics for Building Envelope Adaptation. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beermann, K.; Chen Austin, M. An Inspection of the Life Cycle of Sustainable Construction Projects: Towards a Biomimicry-Based Road Map Integrating Circular Economy. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrier, P.; Glaus, M.; Raufflet, E. BiomiMETRIC assistance tool: A quantitative performance tool for biomimetic design. Biomimetics 2019, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farjana, S.H.; Mahmud, M.A.P.; Huda, N. Impact analysis of goldsingle bondsilver refining processes through life-cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.O.; Gaspar, P.; de Brito, J. On the concept of sustainable sustainability: An application to the Portuguese construction sector. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstruktionspraxis Article: Why the Combination of Bionics and AI Is so Promising. Available online: https://www.synera.io/news/promising-combination-ai-bionics (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Building Circularity into Nationally Determined Contributions—Learning for Nature. Available online: https://www.learningfornature.org/en/building-circularity-into-nationally-determined-contributions/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- BiomiMETRIC Assistance Tool: A Quantitative Performance Tool for Biomimetic Design. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2313-7673/4/3/49 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Austin, M.C.; Beermann, K.; Austin, M.C.; Beermann, K. Including Nature-Based Success Measurement Criteria in the Life Cycle Assessment. In Life Cycle Assessment—Recent Advances and New Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Why Nature-Based Solutions Are Critical for Climate Change Adaptation. UNDP Climate Promise. Available online: https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/why-nature-based-solutions-are-critical-climate-change-adaptation (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Castelo, S.; Amado, M.; Ferreira, F. Challenges and Opportunities in the Use of Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Adaptation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education for Climate Action: Integrating Education into Nationally Determined Contributions. Documents. Global Partnership for Education. Available online: https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/education-climate-action-integrating-education-nationally-determined-contributions (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Toolbox for Teaching Climate & Energy. NOAA Climate.gov. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/teaching/toolbox (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Curriculum. Climate Change Education. Available online: https://climatechange.stanford.edu/curriculum (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Technology Readiness Levels (TRL). Available online: https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/Shaping_the_Future/Technology_Readiness_Levels_TRL (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Huyton, E. Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 1 to 9 Explained. DefProc. 2024. Available online: https://www.defproc.co.uk/insights/technology-readiness-level-trl-explained/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Solano, T.; Bernal, A.; Mora, D.; Austin, M.C. How bio-inspired solutions have influenced the built environment design in hot and humid climates. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1267757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil, R.; Yuvaraj, S. A comprehensive review on bioinspired solar photovoltaic cells. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 1068–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, N.; Kim, O.N.; Tokimitsu, T.; Nakai, Y.; Masuda, H. Optimization of anti-reflection moth-eye structures for use in crystalline silicon solar cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2011, 19, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, M.J.; Sim, Y.H.; Cha, S.I.; Lee, D.Y. Leaf Anatomy and 3-D Structure Mimic to Solar Cells with light trapping and 3-D arrayed submodule for Enhanced Electricity Production. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.J.; Al-Nakeeb, K.; Petersen, B.; Dalén, L.; Blom, N.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T. Complete mitochondrial genome of the Oriental Hornet, Vespa orientalis F. (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2017, 2, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Ward, J.E.; Liu, X.; Yin, B.; Fu, T.; Chen, J.; Lovley, D.R.; Yao, J. Power generation from ambient humidity using protein nanowires. Nature 2020, 578, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Liang, P.; Jiang, Y.; Hao, W.; Miao, B.; Wang, D.; Huang, X. Stimulated electron transfer inside electroactive biofilm by magnetite for increased performance microbial fuel cell. Appl. Energy 2018, 216, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G. Bio-Inspired Wind Turbine Blade Profile Design. 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10829/8227 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Wayne, B.M.; Santoso Mintorogo, D.; Arifin, L.S. Biomimicry Kinetic Facade as Renewable Energy. Acesa 2019, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, I.A.; Mahmoud, M.Y.; Abdelfattah, M.M.; Metwaly, Z.H.; AbdelGawad, A.F. Computational And Experimental Investigation of Lotus-Inspired Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbine Blade. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2021, 87, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathik, V.; Narayanan, U.K.; Kumar, P. Design Analysis of Vertical Axis Wind Turbine Blade Using Biomimicry. J. Mod. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2021, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittlesey, R.W.; Liska, S.; Dabiri, J.O. Fish schooling as a basis for vertical axis wind turbine farm design. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2010, 5, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, M.; Adamo, G.; Hanna, J.; Auger, J. Towards Sustainable Island Futures: Design for Ocean Wave Energy. J. Futures Stud. 2021, 25, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sheng, W.; Zha, Z.; Aggidis, G. A Preliminary Study on Identifying Biomimetic Entities for Generating Novel Wave Energy Converters. Energies 2022, 15, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xia, W.; Ren, J.; Yu, W.; Feng, H.; Hu, S. Wind energy harvesting inspired by Palm leaf flutter: Observation, mechanism and experiment. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 284, 116971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.-Q.; Zhao, L.; Fu, H.-L.; Yeatman, E.; Ding, H.; Chen, L.-Q. Ocean wave energy harvesting with high energy density and self-powered monitoring system. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, K.; Fujii, K.; Kawano, T.; Wada, S. Bio-mimic energy storage system with solar light conversion to hydrogen by combination of photovoltaic devices and electrochemical cells inspired by the antenna-associated photosystem II. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1723946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, I.; Lizundia, E. Biomimetic Wood-Inspired Batteries: Fabrication, Electrochemical Performance, and Sustainability within a Circular Perspective. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2021, 5, 2100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, L.; Yang, L.; Hamel, J.; Giummarella, N.; Henriksson, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, H. Bioinspired Ultrastable Lignin Cathode via Graphene Reconfiguration for Energy Storage. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3553–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Deng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Gao, X.; Tang, S.; Cao, Y.C. Study on sucrose modification of anode material Li4Ti5O12 for Lithium-ion batteries. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-H.; Hsu, W.-S.; Preet, A.; Yeh, L.-H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Pao, Y.-P.; Lin, S.-F.; Lee, S.; Fan, J.-C.; Wang, L.; et al. Ingestible polysaccharide battery coupled with a self-charging nanogenerator for controllable disinfection system. Nano Energy 2021, 79, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qin, X.; Tian, Y.; Luo, Q.; Yao, H.; Wang, J.; Dang, C.; Xu, Q.; Lv, S.; Xuan, Y. Biomimetic optimized vertically aligned annular fins for fast latent heat thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Rao, Z. Biomimetic phase change capsules with conch shell structures for improving thermal energy storage efficiency. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tero, A.; Takagi, S.; Saigusa, T.; Ito, K.; Bebber, D.P.; Fricker, M.D.; Yumiki, K.; Kobayashi, R.; Nakagaki, T. Rules for biologically inspired adaptive network design. Science 2010, 327, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamatzky, A.; Martínez, G.J.; Chapa-Vergara, S.V.; Asomoza-Palacio, R.; Stephens, C.R. Approximating Mexican highways with slime mould. Nat. Comput. 2011, 10, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adamatzky, A.; Alonso-Sanz, R. Rebuilding Iberian motorways with slime mould. Biosystems 2011, 105, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Pinzón, O.; Aguilar Gallardo, O.; Chen Austin, M. A Bio-Optimization Approach for Renewable Energy Management: The Case of a University Building in a Tropical Climate. Energies 2025, 18, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royall, E.; Lang, W. Defining Biomimicry: Architectural Applications in Systems and Products. Center for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://docslib.org/doc/7925086/defining-biomimicry-architectural-applications-in-systems-and-products (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Prasann, S.; Gurram, G.; Engineering, E. A novel electricity generation with green technology by Plant-e from living plants and bacteria: A natural solar power from living power plant. In Proceedings of the 2017 6th International Conference on Computer Applications In Electrical Engineering-Recent Advances (CERA), Roorkee, India, 5–7 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Pigments Absorb Solar Energy—Biological Strategy—AskNature. Available online: https://asknature.org/strategy/pigments-absorb-solar-energy/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Chen, H.; Dong, F.; Minteer, S.D. The progress and outlook of bioelectrocatalysis for the production of chemicals, fuels and materials. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirniazmandan, S.; Rahimianzarif, E. Biomimicry, An Approach Toward Sustainability of High-Rise Buildings. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2018, 42, 1837–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiron, R.; Mallon, F.; Dias, F.; Reynaud, E.G. The challenging life of wave energy devices at sea: A few points to consider. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Aggidis, G.A. Nature rules hidden in the biomimetic wave energy converters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 97, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodón, A.; Quintero, V.; Austin, M.C.; Mora, D. Bio-inspired electricity storage alternatives to support massive demand-side energy generation: A review of applications at building scale. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Liu, Q.; Pei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Lin, S.; Chen, W.; Ling, S.; Kaplan, D.L. Bioinspired Energy Storage and Harvesting Devices. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2001301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, I.K.; Galli, V.; Lamanna, L.; Cataldi, P.; Pasquale, L.; Annese, V.F.; Athanassiou, A.; Caironi, M. An Edible Rechargeable Battery. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2211400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, V.S.C. 7 Modelo de Optimización Combinatoria Para Bioflujos del Transporte; Libros Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia: Virtual, 2019; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Mu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, C.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Cui, M. Multi-objective microgrid optimal dispatching based on improved bird swarm algorithm. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2022, 5, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CBC [10] | Proposed Function of the Coupled Bio-Inspred and ETS [10] | Biomimicry Principle/Pinnacle Analogy | Interpretation for Energy Transition | Policy Instrument | Instrument Applicability Scale ** | Instrument Purpose/Function *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-technical factors | Respond to global societal and environmental challenges such as land rush, uneven distribution, and the lack of budget as cost-benefit solutions. | Symbiotic cooperation among species ensuring shared benefits within limited ecosystems. | Bio-inspired governance mechanisms emulate mutualism and resource sharing, enabling fair access to clean energy. | Global carbon tax *, international climate finance, inclusive energy governance frameworks. | Global/supranational | Establish shared accountability and equity in emissions reduction; ensure fair resource distribution and financial support for developing nations. |

| Urban infrastructure regime | Help stakeholders and landowners to use aggregated incentives and other available financial and institutional re-sources. | Rewarding species that enhance system-wide efficiency (e.g., mycorrhizal networks). | Biomimetic coordination in smart grids and distributed networks modeled on cooperative biological systems. | Green infrastructure bonds, public–private partnerships, adaptive regulatory frameworks. | National/metropolitan | Mobilize capital and foster institutional collaboration for adaptive, bio-inspired energy and infrastructure systems. |

| Social innovation (niche) | Coupled solar panels and green infrastructure may have multiple benefits in terms of better cooling effects and less environmental disturbances. | Mycorrhizal fungi and underground networks distribute nutrients and information for mutual resilience. | Represents local biomimicry niches that incubate transition pathways at pilot scales. | Living labs, innovation vouchers, community energy cooperatives. | Local/regional | Promote participatory experimentation and co-creation of bio-inspired energy solutions; accelerate niche innovation and social learning. |

| Natural capital | People can become familiar with both renewable energy technologies and natural infrastructure living labs at the same place and access real time data. | Regeneration and care of progeny in ecosystems; principles of strong biomimicry. | Regenerative design replenishes ecosystems while producing energy. | Ecosystem service valuation, biodiversity credits, payments for ecosystem services (PES). | Regional/national | Internalize ecological value within energy and economic planning; incentivize regenerative and restorative design. |

| Energy landscape | Smoothly transform traditional infrastructure to new natural infrastructure, e.g., use contaminated lands as natural capital for renewable energies. | Tree leaves and soil organisms recycle carbon and nutrients. | Bio-inspired land use that transforms energy landscapes into regenerative carbon sinks. | Land use planning reforms, renewable zoning, restorative energy programs. | Regional/municipal | Integrate bio-inspired land management and renewable infrastructure, transforming degraded areas into regenerative energy landscapes. |

| Resource management | Support both waste and resources management by using less land, efficiency, or using more sustainable resources. | Mycelium networks and circular metabolism in ecosystems. | Circular energy loops emulating natural metabolism for waste minimization and nutrient reuse. | Circular economy regulation, industrial symbiosis platforms, eco-labeling standards. | National/sectoral | Promote closed-loop material and energy flows across industries, enhancing efficiency and reducing waste. |

| Urban ecosystem services | Support more services in terms of ecosystem restoration and conservation, energy efficiency and learning services in urban areas for people. | Cooperative adaptation and interspecies resilience in ecosystems. | Bio-inspired energy infrastructures deliver co-benefits (cooling, air quality, biodiversity). | NbS design guidelines, urban restoration funds, environmental education policies. | Municipal/community | Enhance biodiversity, microclimate regulation, and social well-being through nature-based urban energy interventions. |

| Land sink | Reduce embodied carbon emissions by using natural environments, land, and renewable energies. | Soil organisms and carbon-sequestering plants converting waste into resources. | Integrates biomimicry for carbon capture and regenerative land-energy systems. | Carbon pricing *, soil carbon credits, regenerative agriculture incentives. | National/local (rural) | Stimulate carbon sequestration and restoration practices that transform land into active carbon sinks supporting net zero goals. |

| Challenges | Recommendation/Action Area | Core Requirement/Mechanism | Rationale/NDC Goal Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formalizing Bio-Inspired Design Language in NDCs | |||

| Without formal recognition of biomimetics, there is a risk that countries will meet their NbS quotas with minimal, easily implemented projects, failing to drive the deep technological and systemic shifts required for long-term climate resilience. | Elevating NbS to NbI (Nature-based Innovation) | Explicitly recognize Nature-based Solutions (NbS) as the foundation for Nature-based Innovation (NbI), encouraging the systematic extraction of functional, resource-efficient principles via biomimetics. | Compels rigorous R&D and interdisciplinary planning, ensuring NbS is not relegated to minimal projects. |

| NDC implementation requires “new and innovative approaches to unlock finance and support for developing country Parties at scale” and relies heavily on technology transfer [29]. Investors are often hesitant regarding complex, novel climate technologies. | Explicit Technology Transfer Pathways | Mandate the inclusion of specific biomimetic and bionic research and development (R&D) in Technology Needs Assessments (TNAs). | Elevates technologies, such as AI-driven bionics for lightweight material optimization [43], to nationally supported climate technologies eligible for international finance and transfer. |

| Increases ambition beyond the current low 28% CE explicit mention rate [44]. | Specific Circularity and Regenerative Targets | Introduce mandatory quantitative targets for resource efficiency based on biological standards; promote bio-based materials and mandate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) tools. | Ensures evaluation of material choices in infrastructure projects via indices comparable to natural systems. |

| Financing the Bio-Shift and Measuring Impact | |||

| Strive for bio-inspired design-dedicated financing mechanisms and rigorous, tailored performance metrics, such as the ones proposed in [45,46]. | Blending Finance for Bio-Innovation | Commit to leveraging national budgets, private investment, and multilateral funds (GCF) to de-risk pilot projects, e.g., bio-adaptive infrastructure [47] (bio-adaptive coastal protection zones or self-regulating, and passively cooled urban structures [48]). | Unlocks new finance and support via mechanisms like Green Bonds earmarked for innovation demonstrating biomimetic/bionic resource efficiency gains. |

| Developing Mitigation Metrics | Integrate Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): tracking Material Intensity Reduction (MIR) and Embodied Carbon Efficiency (ECE) achieved through bionic optimization [43]. | Provides a quantifiable link between bio-inspired structural efficiency and industry/building sector mitigation goals. | |

| Developing Adaptation Metrics | Integrate Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): measure resilience using a Functional Performance Index (FPI) assessing structural longevity, self-repair, and multi-functional ecological benefits. | Provides a robust comparison against conventional infrastructure. | |

| Integrating Biomimicry into Capacity Building | |||

| Many parties have identified capacity needs specifically related to technology deployment. Energy demand or urban metabolism reduction via more “educated” users. | Curriculum Standardization (ACE) | Integrate biomimicry and ecological literacy as required components of national Climate Action Education (ACE) strategies [49,50,51]. | Directly addresses the need for systems thinking and knowledge transfer, empowering youth as future drivers of the green economy and net zero commitments. |

| The development of the specialized workforce needed for the green economy depends on incorporating bio-inspired systems thinking into capacity building efforts. | Targeted Professional Training | Establish standardized training programs for architects, engineers, urban planners, and manufacturers focused on bio-based materials, LCA, passive biomimetic cooling, among others. | Ensures the workforce is equipped to implement regenerative design at scale [34]. |

| Criterion | Indicator | Unit/Assessment | Relevance to Biomimicry/APC | Justification | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Functional Performance Index (FPI) | Dimensionless index or specific output (e.g., kWh/kg) | Quantifies the multi-functionality (design excellence) and efficiency relative to a conventional baseline. | Quantifies the success of emulating nature’s multi-functionality and performance-per-mass, which is a core tenet of efficient biological design. Critical for lightweight, integrated energy systems. | Biological Multi-Functionality: The ability of a single structure like a leaf to optimize fluid flow, gas exchange, and energy harvesting simultaneously. |

| Material Intensity Reduction (MIR) | Percentage reduction | Tracks the reduction in virgin material mass required per unit of function, focusing on resource efficiency and lightweighting. | Directly addresses the resource demands of the energy transition. Biomimicry often uses scarce, locally available materials, enforcing resource efficiency and reducing embodied carbon (e.g., using hierarchical structures to achieve strength with minimal mass). | Nature’s Material Economy: The efficient use of common elements like carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen over scarce metals. Eco-efficiency metrics. | |

| Environmental | Life Cycle Sustainability Index (LCSI) | Index (0–1) based on ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 | Measures the regenerative potential by assessing full cradle-to-cradle impact, including biodegradability and toxicity, moving beyond CO2 equivalence. | Expands traditional LCA to measure the regenerative potential by including metrics on circularity, toxicity, and end-of-life biodegradability, aligning with the ‘cradle-to-cradle’ ethos of true biomimicry. | Cradle-to-Cradle Design: The framework of William McDonough and Michael Braungart, requiring products to be either biological or technical nutrients. |

| Water Footprint Reduction (WFR) | Liters of water saved per unit of energy | Critical for resilience and sustainable operation in water-scarce regions, inspired by nature’s water management. | Water scarcity is a critical resilience factor for future energy systems (e.g., cooling power plants). Emulating nature’s closed-loop water strategies (e.g., fog harvesting) ensures the energy solution is ecologically compatible. | Nexus Thinking: The energy-water-food nexus where reducing water use improves system resilience. Biological water management (e.g., desert beetles). | |

| Economic | Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE-B) | EUR€/MWh or USD$/MWh | LCOE adjusted for biomimetic benefits (e.g., lower maintenance and materials costs) over the system’s full lifetime. | A standard economic metric, but adjusted to factor in the long-term cost benefits of biomimicry, such as reduced maintenance costs (due to self-cleaning/healing) and lower material input (MIR). | Full Cost Accounting (FCA): Moving beyond initial capital expenditure to include externalities and lifetime operational savings. |

| System Resilience Cost (SRC) Avoided | Monetary value of avoided losses/damages | Quantifies the economic value of increased reliability due to biomimetic design (e.g., anti-fouling, self-healing). | Translates the reliability and robustness benefits into a financial value. A key metric for de-risking investment in high-impact, novel solutions needed for the APC. | Value of Lost Load (VoLL): A metric used in grid planning to quantify the economic impact of power outages. | |

| Reliability/Robustness | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | TRLs (1–9) | The standard measure of maturity required to guide technology choices and de-risk investment for the APC acceleration. | The essential criterion for guiding policy and funding choices. It identifies the necessary developmental effort (Maturity Gap) required to meet the rapid deployment goals of the APC. | NASA/DoD Standard TRL Scale: A universal tool for comparing technological maturity and risk. |

| Self-Healing/Adaptability Score (SHAS) | Index or MTTR reduction (%) | Assesses the system’s inherent ability to recover from damage (self-healing) or adapt to changing conditions (e.g., flow, temperature), a core tenet of biological systems. | Directly assesses the biological imperative for survival and resilience through autonomous repair and flexible response to environmental change. Essential for minimizing downtime in critical energy infrastructure. | Nature’s Strategies for Resilience: Autonomic repair mechanisms (self-healing polymers) and optimal network topologies (Physarum polycephalum). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen Austin, M.; Chung-Camargo, K. A Perspective on Bio-Inspired Approaches as Sustainable Proxy Towards an Accelerated Net Zero Emission Energy Transition. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120842

Chen Austin M, Chung-Camargo K. A Perspective on Bio-Inspired Approaches as Sustainable Proxy Towards an Accelerated Net Zero Emission Energy Transition. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(12):842. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120842

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen Austin, Miguel, and Katherine Chung-Camargo. 2025. "A Perspective on Bio-Inspired Approaches as Sustainable Proxy Towards an Accelerated Net Zero Emission Energy Transition" Biomimetics 10, no. 12: 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120842

APA StyleChen Austin, M., & Chung-Camargo, K. (2025). A Perspective on Bio-Inspired Approaches as Sustainable Proxy Towards an Accelerated Net Zero Emission Energy Transition. Biomimetics, 10(12), 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120842