1. Introduction

Neck dysfunctions result from musculoskeletal disorders and/or neurologic issues caused by diseases (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [

1] and head and neck cancer (HNC) [

2]) or accidents (e.g., whiplash due to an impact [

3]). Most of these causes yield neck pain [

4] and a reduction in the Range Of Motion (ROM) of the cervical spine (i.e., of the relative motion between the head and the shoulders), since they ultimately lead the patient to reduce their neck’s ROM to avoid pain. Neck pain globally affected 203 million people [

5] in 2020 (i.e., 2450 people per 100,000 population) and has a high social cost [

6] due to absences from work and health care requirements. These data show that neck pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal disorders.

The application of mechanical actions to the patient’s neck by means of neck braces [

3] is one of the physical therapies that is often necessary to either alleviate or even heal neck dysfunctions. Indeed [

4,

7], immobilization, stretching, or passive mobilization of the neck yield benefits in many cases. Neck braces are also used for the measurements [

8,

9] that are necessary to quantify neck impairment or to set up suitable therapy.

Static and dynamic neck braces have been proposed for neck therapies. Static neck braces are mainly collars that allow for the immobilization of the neck at a fixed posture [

3,

10] to match the needs of cervical spine injury (CSI) healing and of post-cervical spine surgery [

11]. Conversely, dynamic neck braces are mechanisms that allow for a guided relative motion between the head and the shoulders and, in general, can be implemented in any type of neck physical therapy.

Serial [

9,

12,

13] and parallel mechanisms [

8,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] have been proposed such as neck braces both for Wearable Assistive Devices (WADs) and for outpatient therapies. Such mechanisms connect a frame, fixed either to the patient’s shoulders (e.g., through a vest) or to the seat the patient is sitting on, to a distal link (end-effector) fixed to the patient’s head (e.g., through a harness surrounding the forehead (i.e., frontal, parietal, and occipital bones) or a chin carrier suitably connected to the back of the head). In serial (parallel) mechanisms, one kinematic chain (a number of kinematic chains (limbs)) with links connected in series joins (simultaneously) these two ending links. In general, Serial Mechanisms (SMs) allow for a ROM that is wider than that of Parallel Mechanisms (PMs), but they are less precise and stiff than PMs. In terms of kinetostatic performance, a good compromise might be a PM with a reduced number of limbs.

The natural motion that the neck allows for the head with respect to the shoulders is a spatial motion with six Degrees Of Freedom (DOFs) where the three translational DOFs have limited ROMs and the three rotational DOFs have large ROMs [

21,

22]. Consequently, a three-DOF spherical or quasi-spherical motion [

23] can approximately mimic this motion. Accordingly, dynamic neck braces with less than three DOFs [

13,

19] perform only specific tasks, whereas those with three [

8,

12,

16,

17,

20] or more (up to six) [

9,

14,

15] are general-purpose, and they are conceived to implement any task.

A reduced number of DOFs facilitates the design of PMs with a reduced number of limbs, since having only one actuated pair per limb, which is located on the frame, is a common design choice. Consequently, in the literature, neck braces based on PM types with three DOFs (3RRS [

8], 3RPS [

16,

17], and 3RXS [

20]

1) are much more common than those with six DOFs (6SPS with a 6-3 [

14] and 6-6 [

15] limb arrangement). The limb number can be further reduced to two by adopting three-DOF single-loop architectures with two actuated joints on the frame and a third near the frame. Here, the use of these types of architectures as neck braces is investigated and a novel type of dynamic neck brace is proposed together with the kinematic analysis and dimensional synthesis thereof. The proposed neck brace can be sized to generate both spherical and quasi-spherical motion since it is based on a non-overconstrained single-loop three-DOF spatial architecture.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides the necessary background materials, identifies the design requirements of a general-purpose dynamic neck brace, and presents the architecture of the novel dynamic neck brace together with its kinematic and singularity analyses. Then,

Section 3 uses the relationships deduced in the previous section to address the dimensional synthesis of the proposed orthosis and the workspace analysis of the mechanism. Finally,

Section 4 discusses the obtained results, and

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

Analysis of the neck’s natural motion is central to the definition of the design requirements of a dynamic neck brace. In this section, neck biomechanics is firstly briefly recalled to identify these requirements. Then, the selection of the proposed single-loop architecture is discussed with reference to the literature on dynamic neck braces and on spherical 3-DOF non-overconstrained PMs. Eventually, the kinematics of the proposed mechanism is studied to deduce all the relationships needed to size it according to given motion requirements.

2.1. Summary of Neck Biomechanics and Identification of Neck Brace Requirements

The kinematic constraint that the neck imposes on the relative motion between the head and the shoulders in healthy subjects and patients with neck injuries has been analyzed in many papers (see, for instance, [

24,

25,

26,

27]) and textbooks (see, for instance, [

21,

22]).

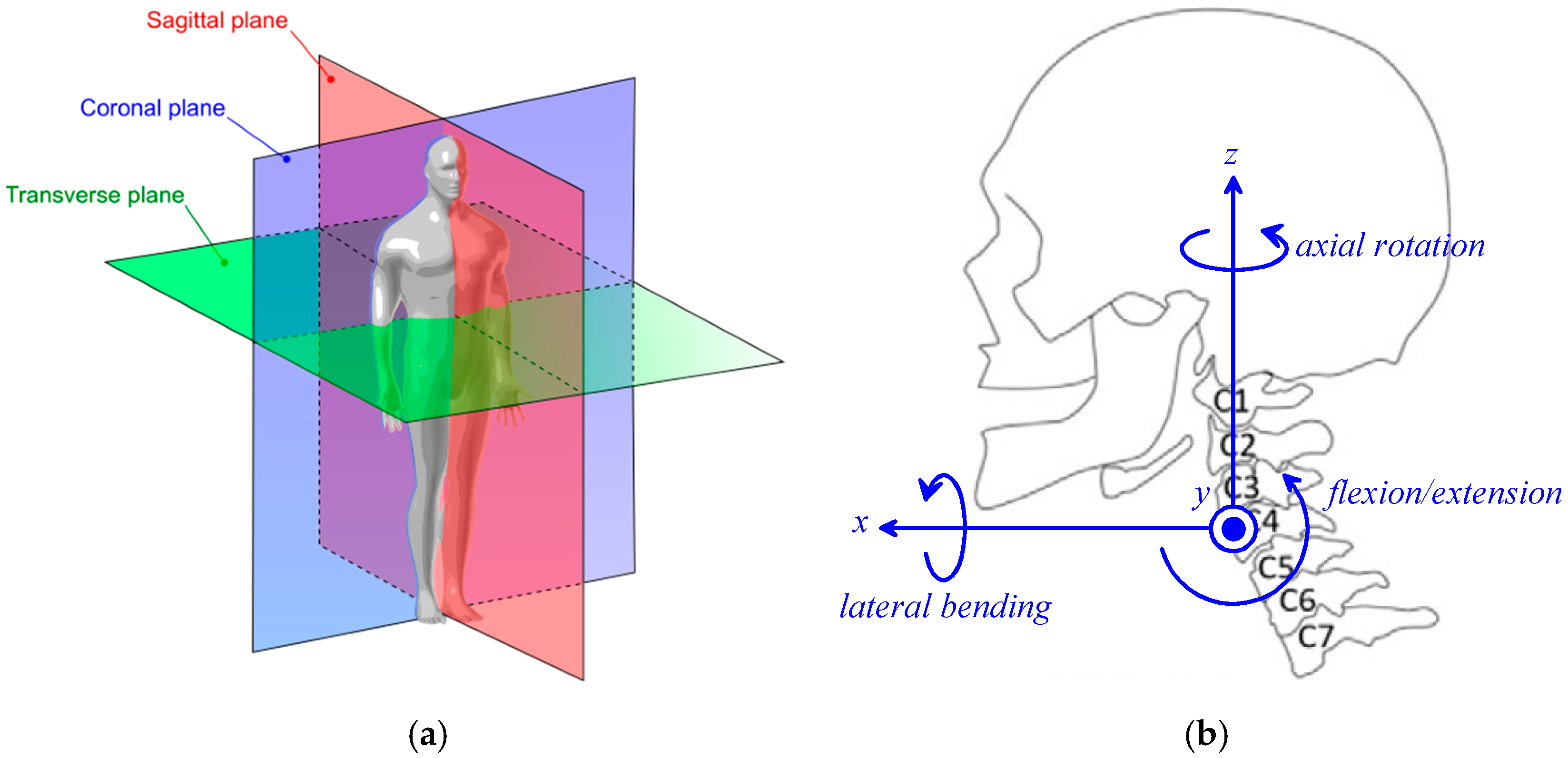

The head displacements are measured by taking as pose reference the

standard anatomical position (see chapter 1.4A of Ref. [

28]), also named

Frankfurt plane, and hereafter referred to as

neutral position. The neutral position of the head (

Figure 1b) is the one assumed by the skull when the subject is standing upright and looking straight ahead (

Figure 1a) with the orbitales (eye sockets), lower margins of the orbits, and the poria (ear canal upper margins) all lying on the same horizontal plane, which is parallel to the transverse plane (see

Figure 1a). In this pose, introducing the two coincident Cartesian reference systems shown in

Figure 1b, one fixed to the skull and the other fixed to the shoulders, makes it possible to define the following head displacements (note that the xz-coordinate plane coincides with the sagittal plane (see

Figure 1a) and the coordinate planes xy and yz are parallel to the transverse and the coronal plane, respectively):

- -

Counterclockwise rotation around the x-axis, named Right(+)/Left(−) Lateral Bending;

- -

Translation along the x-axis, named Protraction(+)/Retraction(−);

- -

Counterclockwise rotation around the y-axis, named Flexion(+)/Extension(−);

- -

Translation along the y-axis, named Left(+)/Right(−) translation;

- -

Counterclockwise rotation around the z-axis, named Left(+)/Right(−) Axial Rotation;

- -

Translation along the z-axis, named Upward(+)/Downward(−) translation.

From a mechanical point of view, the cervical spine consists of seven links (see

Figure 1b), the vertebrae C1 (atlas), C2 (axis), C3, …, C7, that connect the occipital bone (O) of the skull to the first vertebra of the thoracic spine, T1. The intervertebral joints O-C1 and C1–C2 have a structure that is different from the remaining joints. Nevertheless, in general, all the intervertebral joints can be considered as spherical pairs with a limited mobility that, in the O-C1, is very limited in all the coordinate planes and, in the C1-C2, is much larger in the horizontal plane (axial rotation). Consequently, the number of DOFs of the cervical spine is higher than six. Even though the cervical spine is a redundant spatial kinematic chain, the limited ROM of each intervertebral joint makes the translation of the skull with respect to the shoulders an unnatural motion, limited to few centimeters along the x axis [

29] and negligible along the y and z axis, which, in practice, reduces the actual number of DOFs mainly to three rotations. Mechanisms that try to replicate the kinematic structure of the cervical spine have been presented in the literature (see, for instance, [

30,

31]).

The fact that rotations are prevalent in neck motion has led to the characterization of head mobility by evaluating only these three rotations using different measurement techniques [

32]. Almost all the reported measurements consider these three movements as independent planar motions occurring in the three coordinate planes (i.e., the sagittal, horizontal, and coronal planes for flexion/extension, axial rotation, and lateral bending, respectively), and give their extreme values when performed starting from the neutral position.

Table 1 summarizes these values as presented in [

21] and

Table 2 provides the contribution to the ROM due to each intervertebral joint as presented in [

22]. These values suggest the adoption of the values reported in

Table 3 for the ROM of a dynamic neck brace that has to match the motion needs of nearly all potential patients. Also, if a 3-DOF spherical/quasi-spherical mechanism is adopted, the fact that the neck anatomy allows very limited translations leads the designer to impose that the spherical motion center (SMC) of the brace be located on the cervical spine more or less in the middle (i.e., at the level of vertebra C4 (see

Figure 1b). Indeed, this choice minimizes the relative translation between two adjacent vertebrae that occurs when the patient’s neck has to follow the motion imposed by the dynamic neck brace. The best position of the SMC could also be determined through self-alignment techniques similar to the ones presented in [

33,

34], when the patient starts wearing the brace, by making the patients move their head with a brace that follows these movements with the calibration joints unlocked. Below,

Section 4 discusses how to locate the SMC in greater depth.

2.2. The RRU-RRS Mechanism

From an architectural point of view, as explained above, a 3-DOF, spherical, non-overconstrained, single-loop mechanism is a good compromise, combining structural simplicity with good stiffness and a sufficiently large workspace, as well as the potential for quasi-spherical motion. The type synthesis of spherical 3-DOF mechanisms has been addressed in the literature [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], and single-loop architectures have been identified.

The Chebychev–Grübler–Kutzbach criterion and Euler’s formula [

40,

41] applied to single-loop mechanisms yield

where

l is the mechanism’s DOF number,

n is the link number,

ci is the number of joints with

i DOFs, and

f is the DOF number of the free rigid body, which is equal to 6 for spatial motion and to 3 for spherical motion. A single-loop spherical mechanism, that is, with

l ≥ 1 for

f = 3 in Equation (1), is overconstrained if Equation (1) gives

l ≤ 0 for

f = 6, and non-overconstrained otherwise. This means that, if the geometric conditions that impose the spherical motion of all the links are not satisfied, overconstrained mechanisms become isostatic (

l = 0) or hyperstatic (

l < 0) structures and jam, whereas non-overconstrained ones remains hypostatic (

l ≥ 1) structures and keep moving with a spatial quasi-spherical motion. Consequently, a single-loop 3-DOF neck brace requires a spherical non-overconstrained architecture yielding

l = 3 for

f = 6 in Equation (1) to enable the distal link to execute both spherical and quasi-spherical motion. Moreover, in such a mechanism, each of the two limbs simultaneously connecting the frame and the distal link must have a

connectivity of at least 3. By extension from [

42], the

limb connectivity is defined as the number of DOFs that the distal link would possess, with respect to the frame, if it were connected to the frame only by that limb. Indeed, the number of DOFs of the relative motion between the distal link and the frame cannot be higher than the minimum value of the connectivity of the limbs.

Based on the considerations outlined above, the 3-DOF spherical, non-overconstrained, single-loop architecture proposed here was derived from a spherical architecture of type n RRR-RRS (

Figure 2a) where all of the R-pair axes share a common intersection point (point C in

Figure 2a). Having a common intersection point shared by all of the R-pair axes is the geometric condition that imposes the spherical motion on all of the links, with this point serving as the SMC. This particular RRR-RRS architecture consists of two limbs, one of type RRR and the other of type RRS, that simultaneously connect the distal link to the frame. The RRR limb, which has a connectivity of three, makes the distal link perform only spherical motion with respect to the frame, since the axes of its three R pairs share a common point. Conversely, the RRS limb, which has a connectivity of five, only limits/controls the spherical motion imposed by the RRR limb. For this architecture, Equation (1) gives five DOFs for

f = 3, but only three DOFs are possible for the distal link due to the RRR limb (i.e., the remaining two DOFs are idle and could be eliminated by replacing the S pair with another R pair whose axis passes through the SMC), but, unfortunately, only two DOFs for

f = 6. Therefore, if the geometric condition that guarantees the spherical motion is violated, this mechanism will perform a quasi-spherical motion with only two DOFs, which are not sufficient for its application in a neck brace. This problem is solvable by adding an idle R pair at the end, adjacent to the distal link, of the RRR limb whose axis is perpendicular to the axis of the third R pair of this limb (

Figure 2b). The resulting architecture is of type RRU-RRS (

Figure 2b), where U stands for universal joint. The U joint of the RRU limb is constituted by two mutually orthogonal R pairs: the first one is not adjacent to the distal link, with axis passing through the SMC of the old RRR limb, and the second one is adjacent to the distal link. For this new mechanism, the following statement gives the geometric condition that guarantees the spherical motion of all links.

Statement. In an RRU-RRS mechanism, if, out of singularities, the axes of the first three R pairs of the RRU limb and of the two R pairs of the RRS limb share a common intersection point, all the links are constrained to perform a spherical motion with the common intersection point being the SMC.

The proof of this statement is as follows.

Proof. In the RRU limb, the two links that join the three joints of this limb and the cross link of the U joint (link 4 in

Figure 2b), when manufactured and assembled so that the axes of the first three R pairs share a common intersection point, physically keep this point shared during motion. Therefore, they are physically constrained to perform a spherical motion with this shared point as the SMC, hereafter termed SMC

RRU, and the center of the U joint (point C

U in

Figure 2b), which is the intersection point of the axes of the two mutually orthogonal R pairs constituting the U joint, must always move on a sphere centered at SMC

RRU.

Moreover, in the RRS limb, if the link that joins the two R pairs is manufactured such that the axes of these two R pairs share a common intersection point, it physically keeps this point shared during motion. Therefore, the two links that join the three joints of this other limb are physically constrained to perform a spherical motion with this intersection point as the SMC, hereafter termed SMC

RRS, which constrains the center of the S joint (point C

S in

Figure 2b) to move on a sphere centered at SMC

RRS.

If such RRU and RRS limbs are assembled in an RRU-RRS mechanism such that SMCRRU coincides with SMCRRS, five of the six mobile links of the mechanism must perform a spherical motion with the same SMC and the two points CU and CS must move on concentric spheres that have this SMC as their center. Therefore, under this condition, if also the distal link, which is the sixth mobile link, performs a spherical motion with the same SMC, the proof of the above statement is complete.

Such a demonstration can be given as follows. The two points CU and CS are points at rest with respect to the distal link and can be considered part of it together with the segment CUCS, which, due to the particular motion of these two points, can only perform a spherical motion with the same SMC as the other five mobile links. Moreover, the U joint forbids the rotation of the distal link around axes that do not lie on the plane that passes through CU and is parallel to its R-pair axes. Therefore, provided that point CS does not lie on this plane, which is a particular geometric condition that can be avoided by suitably sizing the links (i.e., it is a structural singularity), the distal link cannot rotate around the segment CUCS. Since such a rotation is the only motion that would make the distal link perform a non-spherical motion around the same SMC as the other links, the conclusion is that even the distal link must perform such a spherical motion. Q.E.D. □

The thusly deduced spherical RRU-RRS is also obtainable from the spherical non-overconstrained 3RRS architecture proposed in [

43], which was used in [

8] to obtain a quasi-spherical neck brace, by eliminating one RRS limb and, successively, replacing one S pair with one U joint in one out of the two remaining RRS limbs. The 3RRS neck brace proposed in [

8] has been employed for measurements [

44] and rehabilitation therapies [

45,

46,

47]. It has a wide workspace that covers 63% of the flexion/extension ROM, 65% of the axial rotation ROM and 85% of the lateral-bending ROM. Therefore, the structural simplification introduced with the novel RRU-RRS architecture is expected to extend this workspace to meet the design requirements of

Table 3 and to better satisfy all the needs of those measurements and therapies where the 3RRS neck brace is employed.

2.3. Position Analysis of the RRU-RRS Mechanism

In the proposed RRU-RRS neck brace, for all the applications where the brace moves the patient’s head, while remaining fixed to the distal link, the actuated joints are the two R pairs of the RRS limb and the R pair of the RRU limb that is adjacent to the frame, which is fixed to the patient’s shoulders. This choice satisfies the requirement of having two actuated joints on the frame and the third one near the frame.

The position analysis of a mechanism consists of the solution of two problems: the Inverse Position Analysis (IPA) and the Forward Position Analysis (FPA). The IPA is the determination of the actuated joints’ variables for an assigned pose of the output link, which here is the distal link. Conversely, the FPA is the determination of the output link’s pose(s) compatible with assigned values of the actuated joints’ variables. In order to design a control system for the mechanism’s motion, the solution of both these problems is necessary.

Figure 3 shows the notations adopted here. With reference to

Figure 3, the vectors

ui and the angles θ

i, for

i = 2, …, 7, are the axes’ unit vectors and the joints’ variables, respectively, for the six R pairs, and their right subscript

i is the number associated with the R pair they refer to. The angle θ

i, for

i = 2, …, 7, is positive if counterclockwise with respect to

ui, and is equal to zero when the two links joined by the

i-th pair are folded onto one another with the geometric elements of their end joints (i.e., the center for the S pair and the axis for the R pair) lying on the same plane. Points C, C

U, and C

S are the centers of the mechanism’s spherical motion (i.e., the SMC), the U joint and the S pair, respectively. Points C

6 and C

7 are the feet of the perpendiculars from point C

S to the axes of R pairs 6 and 7, respectively. Points C

3, C

2, and C

5 are the feet of the perpendiculars from points C

U, C

3, and C

6, respectively, to the axes of R pairs 3, 2, and 5, respectively.

d2,

d3,

d5,

d6,

dU, and

dS are the distances of points C

2, C

3, C

5, C

6, C

U, and C

S, respectively, from point C; whereas,

d7 is a signed distance defined such that the vector relationship (C

U − C

7) =

d7 u7 holds.

h2,

h3,

h5,

h6, and

h7 are the lengths of the segments C

2C

3, C

3C

U, C

5C

6, C

6C

S, and C

7C

S, respectively, The vectors

v1 and

v7 are unit vectors defined such that the vector relationships (C

S − C) =

dS v1 and (C

S − C

7) =

h7 v7 hold. φ

i and v

i, for

i = 1, 2, 3, are the joint variables and the axial unit vectors, respectively, of a virtual RRR spherical kinematic chain that replaces the S pair to analytically model its kinematics. Finally, α

1, α

2, α

3, and α

5 are the angles formed by the axes of the two R pairs at the ends of links 1, 2, 3, and 5, respectively.

Using the notation defined above, the actuated joints’ variables are θ

2, θ

5, and θ

6, and the following relationships among geometric constants hold:

Equation (2a–c) and

Figure 3 highlight that the independent geometric constants that fully define the mechanism geometry are only 9; that is, the constant angles α

1, α

2, α

3, and α

5 plus the linear constants

dU,

dS,

d7,

h6, and

h7, which allow for the computation of all the remaining constants through Formula (2a–c).

Moreover, the following relationships hold (

Figure 3):

where the three vectors

,

, and

(the three vectors

,

, and

) constitute a right-handed triplet of unit vectors fixed to the frame (to the distal link).

The vector closure equation of the RRU-RRS single-loop mechanism can be written as follows (see

Figure 3):

The dot products of Equation (4) by

,

, and

yield the following system of three scalar equations:

where

System (5), after the introduction of Formula (3a–j), relates the three actuated joints’ variables θ2, θ5, and θ6 to the remaining three R pairs’ variables θ3, θ4, and θ7, which are sufficient to compute the pose of the distal link through Formula (3e,f).

2.3.1. Inverse Position Analysis (IPA)

In the studied mechanism, the IPA consists of determining the values of the three-tuple (θ

2, θ

5, θ

6) compatible with one assigned pose of the distal link. If the pose of the distal link is known (see

Figure 3), the positions of points C

U and C

S are known in a reference system fixed to the frame. Also, since point C and unit vectors

and

are fixed to the frame, unit vectors

and

are also known in the same reference system. As a consequence, the dot products

and

are known. Such products, by exploiting Formula (3d,j), can be written as follows:

where the following identities have been used (see

Figure 3):

Moreover, the replacement of the explicit expressions of

and

given by Formulas (3b,h), respectively, into Formulas (3d,j), respectively, yields

where vectors

and

, for

k = 0,1,2, uniquely depend on θ

3 and θ

6, respectively, through the following explicit formulas:

The above-deduced Equations (7) and (9) allow for the closed-form solution of the IPA as below. Firstly, Equation (7a,b) yield the following values for θ

3 and θ

6:

Successively, for each value of θ

3 and θ

6 computed through Formulas (11a,b), respectively, Equations (9a,b) allow for the computation of the corresponding value of θ

2 and θ

5 through the following formulas:

Formulas (11) and (12) lead to the computation of at most four values of the three-tuple (θ2, θ5, θ6). Consequently, the IPA of the studied mechanism has at most four solutions.

2.3.2. Forward Position Analysis

In the studied mechanism, the FPA consists of the determination of the poses of the distal link (i.e., of unit vectors

and

) compatible with one assigned value of the three-tuple (θ

2, θ

5, θ

6). If the angles θ

2, θ

5, and θ

6 are known (see

Figure 3), the positions of point C

S and unit vectors

and

are known in a reference system fixed to the frame. Also, since point C and unit vectors

and

are fixed to the frame, unit vector

is also known in the same reference system.

Consequently, Formulas (3d,k) make it possible to write the following relationship:

which can be rewritten as follows:

where

Equation (14) is transformable into a quadratic equation in

t = tan(θ

3/2) through the half-angle tangent substitution—that is, the introduction of the trigonometric identities cosθ

3 = (1 − t

2)/(1 + t

2) and sinθ

3 = 2t/(1 + t

2)—and this is then solvable in closed form through the formula

which gives up to two values of θ

3—that is, θ

3,i = 2 arctan(

ti) for

i = 1, 2—and, through Formula (3d), as many values of

and corresponding positions of point C

U.

Since the position of point C

S is known, for each computed position of point C

U, a corresponding vector (C

S−C

U) is computable and, by introducing expression (3e) of unit vector

into Formula (3f), can be used to write the following vector equation:

where the unit vectors

,

, and

constitute a right-handed triplet of unit vectors fixed to link 3 (see

Figure 3). Equation (17) can be rewritten as follows:

where

and

depend only on θ

7 through the formulas

By noting that the triplet of vectors

,

, and

are mutually orthogonal, Equation (18) yields the following solution formulas for θ

4 and θ

7:

The conclusion is that the FPA leads to computing at most four poses of the distal link compatible with one set of values of the actuated joint variables (i.e., of (θ2, θ5, θ6)). Indeed, Equation (16) gives two values for θ3, which, when replaced into Equation (3d), yield as many values for and , whose introduction into Equation (20a) gives at most four values for θ7, to which Equation (20b) associates as many values of θ4. All the FPA solutions are computable through closed-form formulas.

2.4. Instantaneous Kinematics and Singularity Analysis of the RRU-RRS Mechanism

The velocity,

, of point

C, when considered fixed to the distal link, and the angular velocity,

ω, of the distal link are computable by moving from the frame to the distal link along one or the other of the two limbs. This computation yields the following two different analytic expressions for

ω and

(see

Figure 3):

Equating the so-obtained analytic expressions of

ω and

yields the following velocity-loop equations of the studied mechanism:

Equation (22a) is a linear and homogeneous system of three equations in three unknowns that can be written in matrix form as follows:

where the following definitions for the coefficient matrix

M and the unknown vector

ζ have been introduced

If det(

M) ≠ 0, system (23) admits only the trivial solution

ζ =

0, which corresponds to

(see Equations (21a) and (21b)) and makes the distal link perform a spherical motion with point

C as its SMC. Conversely, if det(

M) = 0, system (23) admits an infinity of solutions for

ζ, which can also be non-null; that is, a

constraint singularity [

48] occurs where the distal link can exit from the spherical motion. From an analytic point of view, the determinant of a 3 × 3 matrix is the mixed product of its column vectors, which, in this case, yields the following formula:

By excluding the case in which one of the three vectors is a null vector, a mixed product is equal to zero if and only if the three involved vectors are all parallel to one plane. In the case under study (see

Figure 3), none of the three involved vectors is a null vector. The two vectors

and

are both perpendicular to

and identify a pencil of parallel planes that are perpendicular to the line passing through points

C and

CS; whereas, the remaining third vector

is perpendicular to the plane of the U joint’s cross link, which is the one located by the three points

C,

C7, and

CU (

Figure 3). Consequently, the parallelism of these three vectors to one plane (i.e., a constraint singularity) can occur if and only if point

CS lies on the plane of the U joint’s cross link. Such a result analytically confirms what was concluded, using kinematic reasoning, in

Section 2.2 when proving the statement reported there. This geometric condition is avoidable by sizing the mechanism such that the triangle C

UCC

S does not degenerate into a segment; that is, by imposing

during the design of the mechanism, and by assembling the mechanism at a configuration where point C

S does not lie on the plane of the U-joint’s cross link. Indeed, if the mechanism is assembled at a non-singular configuration—that is, with point C

S out of the plane of the U-joint’s cross link—the distal link can only perform spherical motions that make the triangle C

7C

UC

S rigidly rotate around the line passing through points

C and

CU, which always keeps point C

S out of the plane of the U-joint’s cross link.

Condition (26) contains only geometric constants of the mechanism (i.e., it is a

structural condition). Therefore, if the mechanism is sized such that it satisfies inequality (26) and is assembled with point C

S out of the plane of the U-joint’s cross link, the possible occurrence of a constraint singularity is definitely excluded and the distal link can only perform spherical motion. This implies that

ζ is always a null vector, which leads to simplification of Equation (22b) as follows:

where the following definitions have been introduced:

Formulas (28) highlight that

A and

B are 3 × 3 matrices that depend on the mechanism configuration. Such matrices are named

Jacobians.

Equation (27) relates the actuated joint rates (i.e.,

,

, and

), which are the instantaneous inputs, to the remaining R-pair joint rates (i.e.,

and

(see Equation 21b)) that are necessary to compute the angular velocity,

ω, which is the instantaneous output, and is sufficient to identify the instantaneous spherical motion of the distal link. This is the

input-output instantaneous relationship of the studied mechanism. Equation (27) allows for the solution of two problems [

49,

50,

51]: the Inverse Instantaneous Kinematics (IIK) problem and the Forward Instantaneous Kinematics (FIK) problem. The IIK problem is the determination of the instantaneous inputs’ values (i.e., in the studied case, of

,

, and

) compatible with one assigned set of instantaneous outputs (i.e., in the studied case, of

ω or, which is the same, of

and

). Vice versa, the FIK problem is the determination of the instantaneous outputs’ values (i.e., in the studied case, of

ω or, which is the same, of

and

) compatible with one assigned set of instantaneous inputs (i.e., in the studied case, of

,

, and

).

The IIK and FIK solutions depend on the mechanism’s configuration since matrices

A and

B depend on it. The mechanism configurations that make Instantaneous Kinematics (IK) problems indeterminate are the mechanism’s

singularities. Such singularities are collectable into three main groups [

49]: (i) those that make the IIK indeterminate, named serial (or type-I) singularities; (ii) those that make the FIK indeterminate, named parallel (or type-II) singularities; and (iii) those that make both the IK problems indeterminate, named type-III singularities.

At a serial singularity, the output link (i.e., the distal link in the studied case) can stay at rest even though the actuated joint rates are different from zero; that is, it has a local reduction in DOFs since the motion of one or more actuated joints does not affect its motion. Since this kinematic condition identifies configurations that are at the boundaries of the workspace, serial singularities are located at the workspace boundaries, and identifying them is one of the methods used for determining the output link’s workspace.

Conversely, at a parallel singularity, the output link can perform an instantaneous motion even though the actuated joints are at rest; that is, it locally acquires further DOFs since the actuated joints are no longer able to control its motion. Parallel singularities may be located inside the workspace. The virtual work principle demonstrates that, at a parallel singularity, even an infinitesimal external load applied to the output link requires that one or more actuators must apply an infinite generalized torque to equilibrate it. Such a static condition leads to the breakdown either of some actuators or of some links. Therefore, parallel singularities must be identified during the design stage and avoided during operation.

The analysis of Equation (27) reveals that serial singularities satisfy the analytic and geometric condition

and that parallel singularities satisfy this other analytic and geometric condition:

Condition (29) (Condition (30)) is satisfied when the involved unit vectors are coplanar.

The configurations farthest from parallel singularities are those that provide the best kinetostatic performances of a parallel mechanism. In the case under study, these configurations are those that maximize the absolute value of det(

A) (see Equation (30)). From a geometric point of view, the identity

, which implies

, leads to the conclusion that they occur when the plane of the triangle C

SCC

U is perpendicular to the plane of the triangle C

3CC

U (see

Figure 3). Consequently, the angle μ between these two planes plays the role of a

transmission angle for this mechanism and the parameter

, which is dimensionless and equal to 1 (equal to 0) for μ = 90° (for μ = 0 or μ = 180°; that is, at a parallel singularity), is adoptable as a performance index. As a rule of thumb, for this type of application, which does not require high precision and does not involve high loads (it is worth stressing that, when the brace guides the head motion, the head weight still is carried by the neck), a maximum deviation of ±70° from 90° is still acceptable for μ. Thus, in the studied case, the minimum permissible value for s

μ is 0.342.

3. Results

In this section, the above-reported kinematic analyses are used to size an RRU-RRS spherical mechanism that matches the design requirements of dynamic neck braces reported in

Table 3. As stressed in the previous section, the independent geometric constants that fully define the geometry of this mechanism are nine (

Figure 3): the four angles α

1, α

2, α

3, and α

5, plus the five lengths

dU,

dS,

d7,

h6, and

h7. Consequently, the dimensional synthesis problem to address is the determination of the values of these nine constants that make the free-from-singularity orientation workspace of the distal link match the design requirements of

Table 3.

Since the studied mechanism is spherical, the distal link’s orientation workspace remains unchanged when the mechanism is scaled. Scalability is a sought-after feature when designing an orthosis since it must be adaptable to the size of the patient without changing its mobility. In addition, it makes it possible to normalize the linear constants that must be sized. Accordingly, in the studied case, the five constant lengths are replaced by their ratios to dS; that is, by dU/dS, 1 = dS/dS, d7/dS, h6/dS and h7/dS. Therefore, the independent constants to be determined are reduce to eight: the four angles α1, α2, α3, and α5, plus the four dimensionless ratios dU/dS, d7/dS, h6/dS, and h7/dS.

With reference to

Figure 1b and

Figure 3, in order to identify a symmetric brace that is also easy to wear, the following assumptions are introduced:

- (i)

Point C is located at the centroid of vertebra C4 and is the origin of the two Cartesian reference systems (

Figure 1b), one fixed to the frame (i.e., to the shoulders of the patient) and the other fixed to the distal link (i.e., to the skull of the patient), that coincide with one another at the neutral position;

- (ii)

In the frame (link 1), point C and the two R-pair axes fixed to the frame lie on the xy-coordinate plane of the reference system fixed to the frame with the two R-pair axes that are symmetrically located with respect to the sagittal plane (

Figure 1);

- (iii)

In the distal link, the vectors u7, v7, and

are all parallel to the xy-coordinate plane of the reference system fixed to the distal link with the points CU and CS that lie on the yz-coordinate plane of the same reference system;

- (iv)

α1 = 60°, α2 = α5, sinα3 = h6/dS, 0 = d7/dS, 1 = dU/dS, and v1·u4 = cosα1.

The assumption 0 =

d7/

dS leads to

(

Figure 3), which, when combined with the assumptions α

1 = 60°,

v1·

u4 = cosα

1, and 1 =

dU/

dS, leads to the conclusion that

h7/

dS = 1; that is, the triangle CC

UC

S is equilateral. Such a triangle, for the assumptions (ii) and (iii), is located on the yz-coordinate plane of the distal link and, at the neutral position, is perpendicular to the transverse (horizontal) plane (

Figure 1).

Figure 4, shows the frame (link 1) and the distal link (link 7) in a generic configuration together with the Cartesian reference systems

Cxfyfzf, fixed to the frame, and

Cxdydzd, fixed to the distal link, for a mechanism sized in line with the above-listed assumptions. Hereafter,

if,

jf, and

kf (

id,

jd and

kd) will denote the unit vectors, respectively, of the x, y, and z coordinate axes of

Cxfyfzf (of

Cxdydzd). All of the above-listed assumptions leave only the geometric constants α

2 (= α

5) and α

3 (= arcsin(

h6/

dS)) to be determined by imposing the design requirements from

Table 3, and lead to compute the following values of vector components:

where the left superscripts

f or

d on vector symbols denote vectors measured in the reference system fixed to the frame or to the distal link, respectively.

The rotation matrix,

fRd, that transforms a vector,

da, measured in

Cxdydzd to the same vector,

fa, measured in

Cxfyfzf through the relationship

fa = fRd da has the general form

which, by introducing the Cardan angles ψ

1, ψ

2, and ψ

3 of the ZYX convention, yields the following explicit formula:

It is easy to realize that the angles ψ

1, ψ

2, and ψ

3 defined in this way correspond, respectively, to the axial rotation, the flexion/extension, and the lateral bending of the head (

Figure 1b). With reference to

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, the Orientation Workspace (OW) of the distal link can be defined as the set of all the rotation matrices,

fRd, that identify distal link orientations for which β

1, β

2 ≤ α

2 + α

3, in formulas

Since only the sum of α

2 and α

3 enters into Formula (34), without losing generality, the further assumption α

2 = α

3 can be adopted, which makes the limbs more symmetric and reduces the dimensional synthesis to the determination of only one angle. Also, since, in Formula (34), β

1 and β

2 are the lower extreme of the admissible range of values for α

2 + α

3, the dimensional synthesis can be implemented by looking for the maximum values β

1,max and β

2,max of β

1 and β

2, respectively, that are necessary to satisfy all the design requirements of

Table 3 and, then, by choosing α

2 = α

3 > max(β

1,max, β

2,max)/2. From an analytic point of view (

Figure 4), the following relationships hold:

The introduction of the design requirements of

Table 3 into Formula (33) and of the resulting rotation matrix

fRd together with the vector data given by Equation (31) into Formula (35), yields the extreme values of β

1 and β

2 reported in

Table 4. Analysis of

Table 4 reveals that the condition α

2 = α

3 > max(β

1,max, β

2,max)/2 is satisfied by choosing α

2 = α

3 = 56°.

Table 5 summarizes the values of the geometric constants of the RRU-RRS neck brace sized in this way, which satisfy all the design requirements of

Table 3.

By using GeoGebra [

52,

53,

54,

55], an animated 3D kinematic model of the neck brace, sized with the values reported in

Table 5, was built and used to check that, during motion, the singularity conditions, identified in

Section 2.4, do not occur inside the workspace. Such a model controls/changes the mechanism configuration by using the inverse position–analysis relationships determined in

Section 2.3.1 with the distal link orientation that is assigned by the user through the above-defined angles ψ

1, ψ

2, and ψ

3 (see Formula (33) and the accompanying comments). This control algorithm is the same as the one that a controller should use to move the real neck brace during a passive mobilization program for the patient’s neck. The built model is indeed a kinematic digital twin of the mechanism that can be used to simulate its motion.

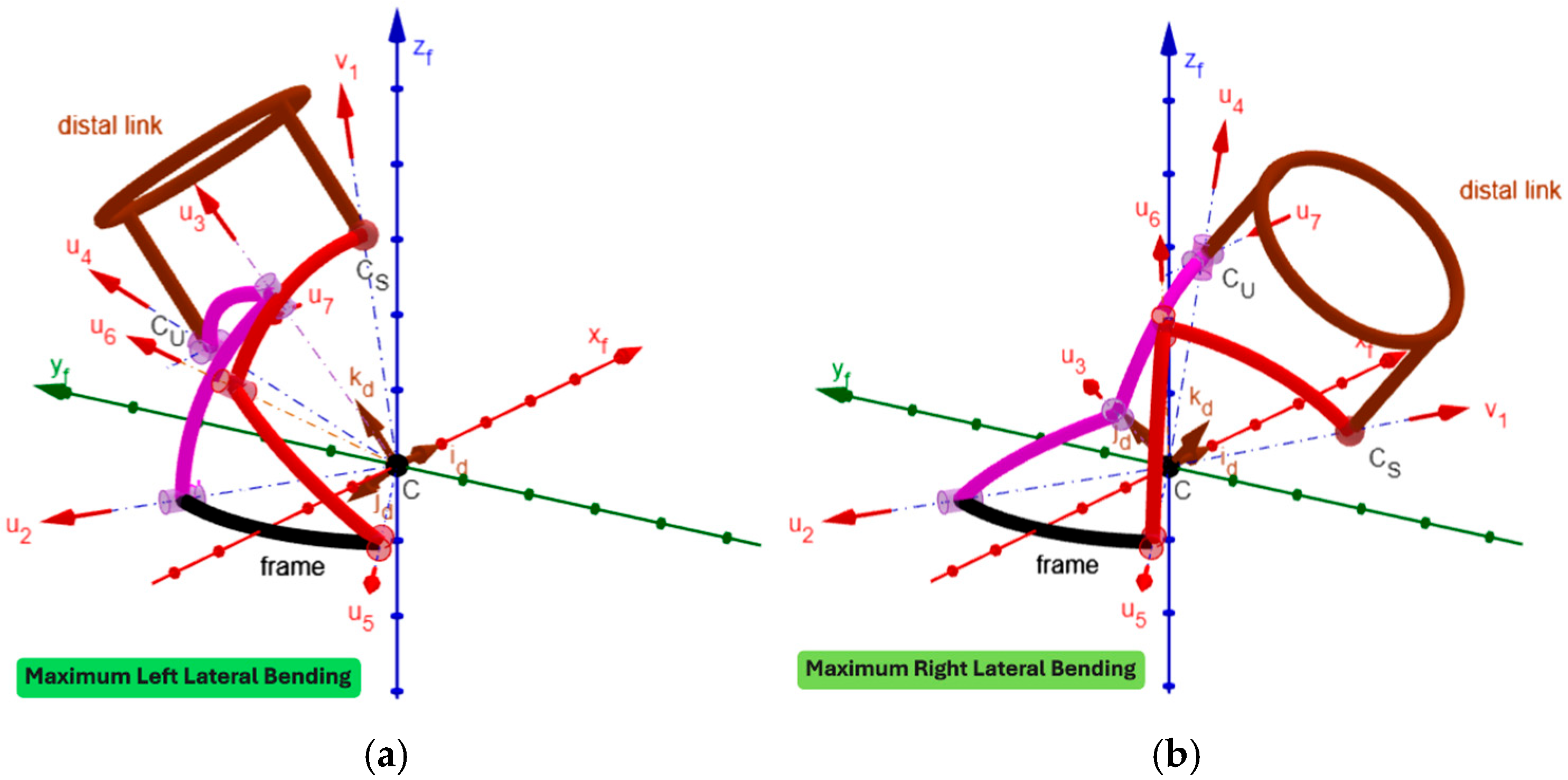

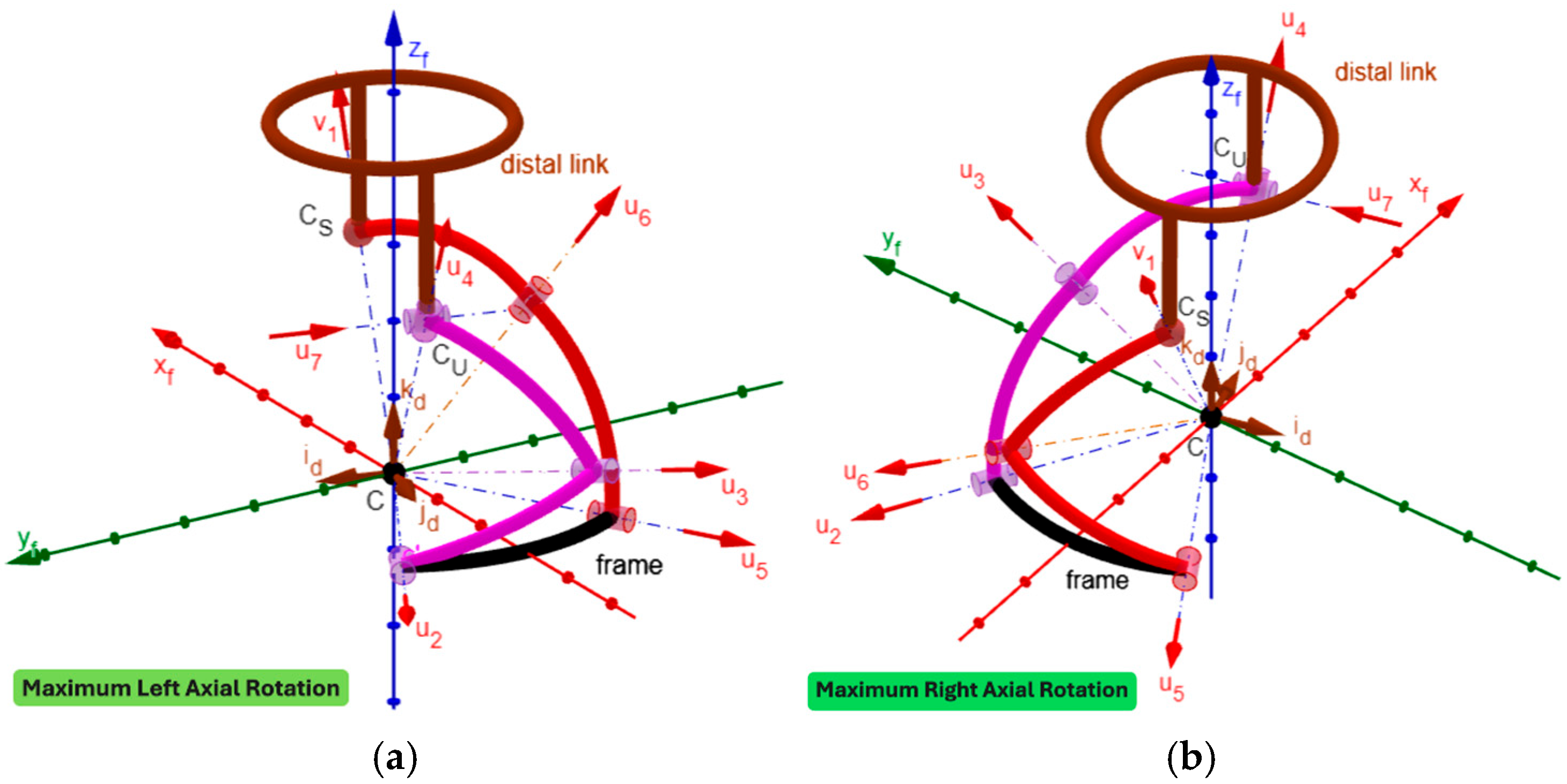

Figure 5 shows the 3D kinematic model built in this way with the distal link at the neutral position, and

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the mechanism configurations with the distal link at the extreme poses of flexion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation, respectively. In the

Supplementary Materials accompanying this paper, the interested reader can find the GeoGebra program used to build the model and four videos that show the neutral position from different points of view, the axial rotation animation, the flexion/extension animation, and the lateral bending animation. These three animations clearly show that the mechanism sized in this way has no singularity inside its workspace.

Regarding the kinetostatic performance, the index sμ is equal to 0.85 (corresponding to μ = 58.31°) at the neutral position. During one cycle of flexion–extension, sμ assumes its minimum value, equal to 0.11 (corresponding to μ = 6.14°), at the maximum extension, and increases with the reduction in the extension, thus reaching its acceptable value (i.e., 0.342) at 55° of extension, its maximum value (i.e., 1) at 28.65° of flexion, and the value 0.82 (corresponding to μ = 54.98°) at the maximum flexion.

During one cycle of axial rotation, sμ assumes its minimum value, equal to 0.6 (corresponding to μ = 36.91° and greater than its minimum acceptable value (i.e., 0.342)), at the maximum right rotation and increases with the reduction in the right rotation, thus reaching its maximum value (i.e., 1) at 33.8° of left rotation and the value 0.77 (corresponding to μ = 50.56°) at the maximum left rotation.

During one cycle of lateral bending, sμ assumes its minimum value, equal to 0.58 (corresponding to μ = 35.3° and greater than its minimum acceptable value (i.e., 0.342)), at the maximum left bending, and increases with the reduction in the left bending, thus reaching the maximum value, equal to 0.98 (corresponding to μ = 77.17°) at the maximum right bending.

In short, only near the maximum extension (i.e., for extensions between 56° and 80°) sμ assumes critical values. Nevertheless, since this region is near the extreme extension, the possible locking of the two passive joints, the one connecting links 2 and 3, and the other one connecting links 3 and 4, is avoidable by introducing a non-linear spring that intervenes only in this region (i.e., an elastic limit switch) to force the joint to unlock.

4. Discussion

The above-reported results can be summarized as follow. The proposed architecture is simple to control since its position–analysis problems are solvable in closed form. In addition, it is able to satisfy all the design requirements of a dynamic neck brace by providing a free-from-singularity workspace that covers the whole ROM of a human neck.

From a manufacturing point of view, the link interferences visible in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 can be easily eliminated by making the links lie on different concentric spherical shells. Moreover, the single-loop architecture of the proposed mechanism makes it possible to mount links 3, 2, 1, 5, and 6 (see

Figure 3) as a serial chain of binary links. This feature makes the intersection of all R-pair axes at the SMC (point C in

Figure 3) much easier to obtain, during the mechanism assembly, than it would be in a multi-loop architecture. Finally, the fact that the proposed architecture has three DOFs when considered as a spatial mechanism (i.e., for

f = 6 in Equation (1)) makes it work as a quasi-spherical mechanism if the intersection of all the R-pair axes at the SMC is not obtained during assembly.

When the mechanism works as a quasi-spherical mechanism (i.e., when the SMCs of the two limbs, named SMC

RRS and SMC

RRU in

Section 2.2, do not coincide with one another), the formulas of the IPA solution reported in

Section 2.3.1 still hold since their deduction does not use the coincidence of SMC

RRS and SMC

RRU. Conversely, those of the FPA solution reported in

Section 2.3.2 do not hold any longer, but the FPA still is solvable in closed form with a technique similar to the one reported in

Section 2.3.2. Consequently, the proposed neck brace remains easy to use even in those applications where the quasi-spherical motion of the neck is not negligible.

How to locate the brace’s SMC (point C in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) on the patient’s neck needs a deeper discussion. In the literature (see, for instance, [

22,

24,

27,

56,

57]), the neck’s movements are analyzed by considering the three neck rotations mainly as three planar motions occurring in three mutually orthogonal planes. This approach leads to the identification of three different Instantaneous Axes of Rotation (IAR) that are mutually orthogonal and change their positions during a finite movement of the neck. Consequently, if these data were available or, as an alternative, the fixed axode [

42] traced by the Instantaneous Screw Axis (ISA) during the neck motion were known, the best location of the brace’s SMC would be the point that minimizes the sum of its distances from all these axes. The determination of such a point is cumbersome, impractical, and, ultimately, unnecessary for making a patient wear a neck brace. Indeed, as stressed in

Section 2.1, the cervical spine is a redundant spatial mechanism. Its redundant mobility makes it able to perform many different paths to move the distal link from one pose to another, provided that the path keeps the joints’ motion within their ROM. This condition is certainly satisfied during a spherical motion of the distal link that has its SMC nearly coincident with the centroid of vertebra C4 (

Figure 1b).

To reach this location, the neck brace must contain additional joints (alignment joints) that make the brace’s SMC (point C in

Figure 3) translate in the sagittal plane by moving the brace’s frame (link 1 in

Figure 3) with respect to the vest that fixes the brace to the patient’s shoulders. Of course, once the brace’s SMC has been correctly located all the alignment joints must be locked. Many planar kinematic chains can provide this two-DOF translation; among these chains, the double parallelogram mechanism (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) may be the most practical since it contains only passive R pairs, which are easy to move and lock.

The identification of the centroid of vertebra C4 on the patient’s neck could be achieved through radiographs, but the use of self-alignment techniques [

33,

34] is more practical for the identification of the best location for the brace’s SMC. In this case, such techniques consist of the implementation of the following steps:

- (i)

The patient, with their shoulders and neck in the neutral position (

Figure 1), wears the brace with the alignment joints unlocked and the actuated joints non-actuated (i.e., with the actuators unpowered and unlocked).

- (ii)

The physiotherapist makes the brace’s SMC lie on the sagittal plane (

Figure 1), the axes of the two R pairs adjacent to the frame (link 1 in

Figure 3) parallel to the transversal plane, and the plane of motion of the alignment joints parallel to the sagittal plane. Then, he fixes the brace’s vest to the patient shoulders and the brace’s distal link (link 7 in

Figure 3) to the patient’s forehead.

- (iii)

The patient sequentially performs one full cycle of flexion/extension, one full cycle of axial rotation, and one full cycle of lateral bending, during which the values assumed by the joint variables of the alignment joints are recorded.

- (iv)

The average values of the joint variables recorded in step (iii) are computed.

- (v)

The physiotherapist locks the alignment joints at the values of their joint variables computed in step (iv) and then makes the patient repeat the three full-cycle motions to check that he does not feel distress or pain in the neck when moving the head and whether a ROM reduction occurs when moving the head with the alignment joints locked in place.

Regarding brace’s wearability, the spherical nature of the proposed brace makes it scalable without affecting its motion and, consequently, its motion control system. Therefore, adapting the size of the brace to the size of the patient can be simply achieved by providing either different brace sizes, or a brace with links whose dimensions are adjustable according to the size of the patient. Also, since the geometric constants that affect the brace’s motion are only the four angles α1, α2, α3, and α5, and the four dimensionless ratios dU/dS, d7/dS, h6/dS, and h7/dS, scaling the brace can be achieved by varying dS while keeping these eight parameters unchanged. This means that, for instance, the shape of the distal link can be modified freely provided that d7/dS and h7/dS are kept unchanged and that similar considerations hold for all the other links. In short, designers have many parameters available to improve the brace’s wearability and adaptability.