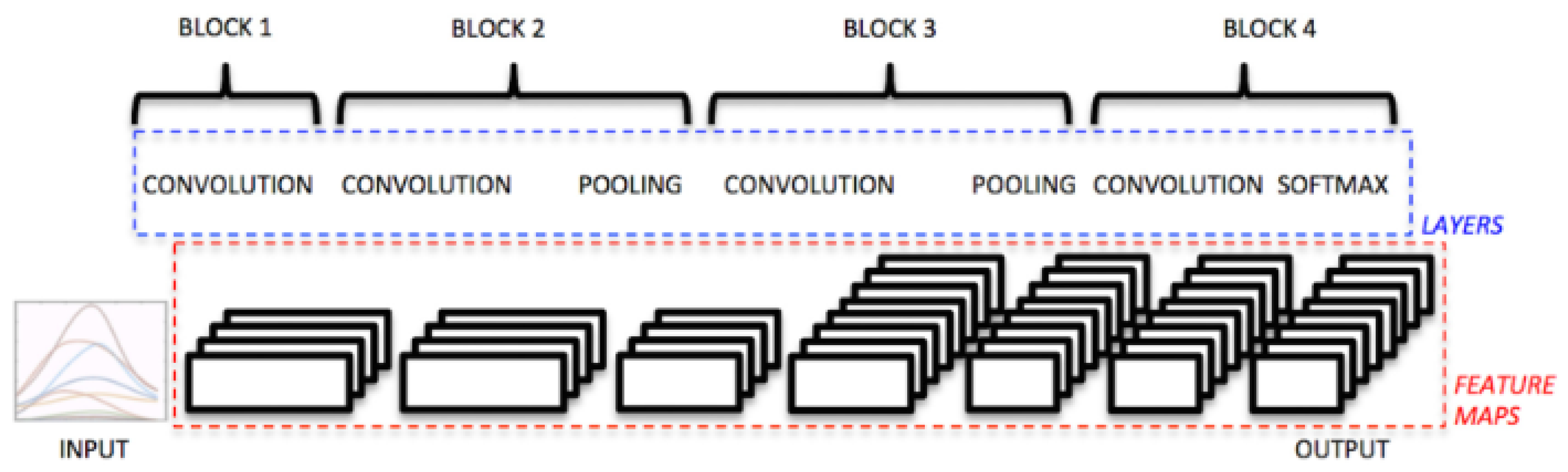

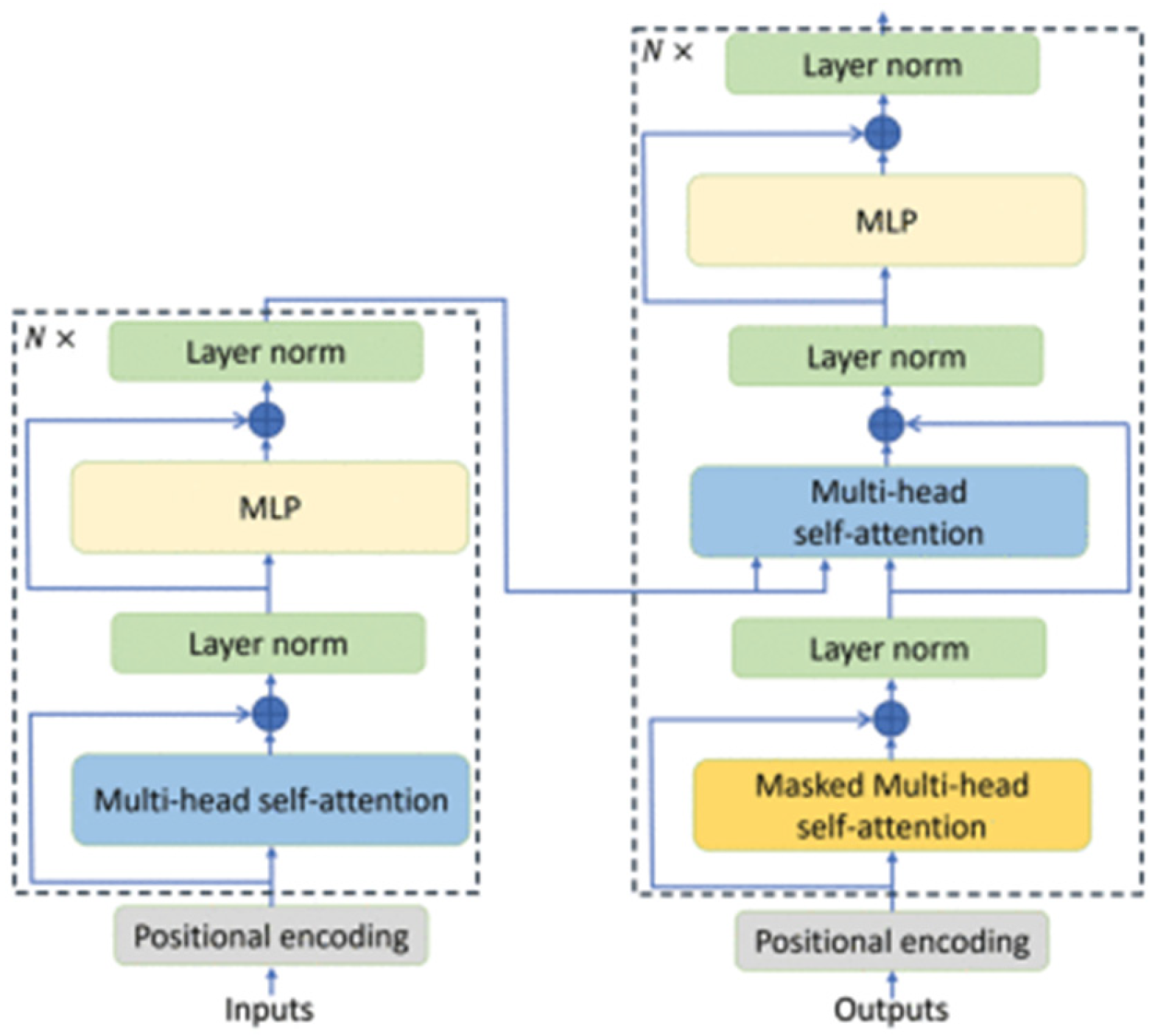

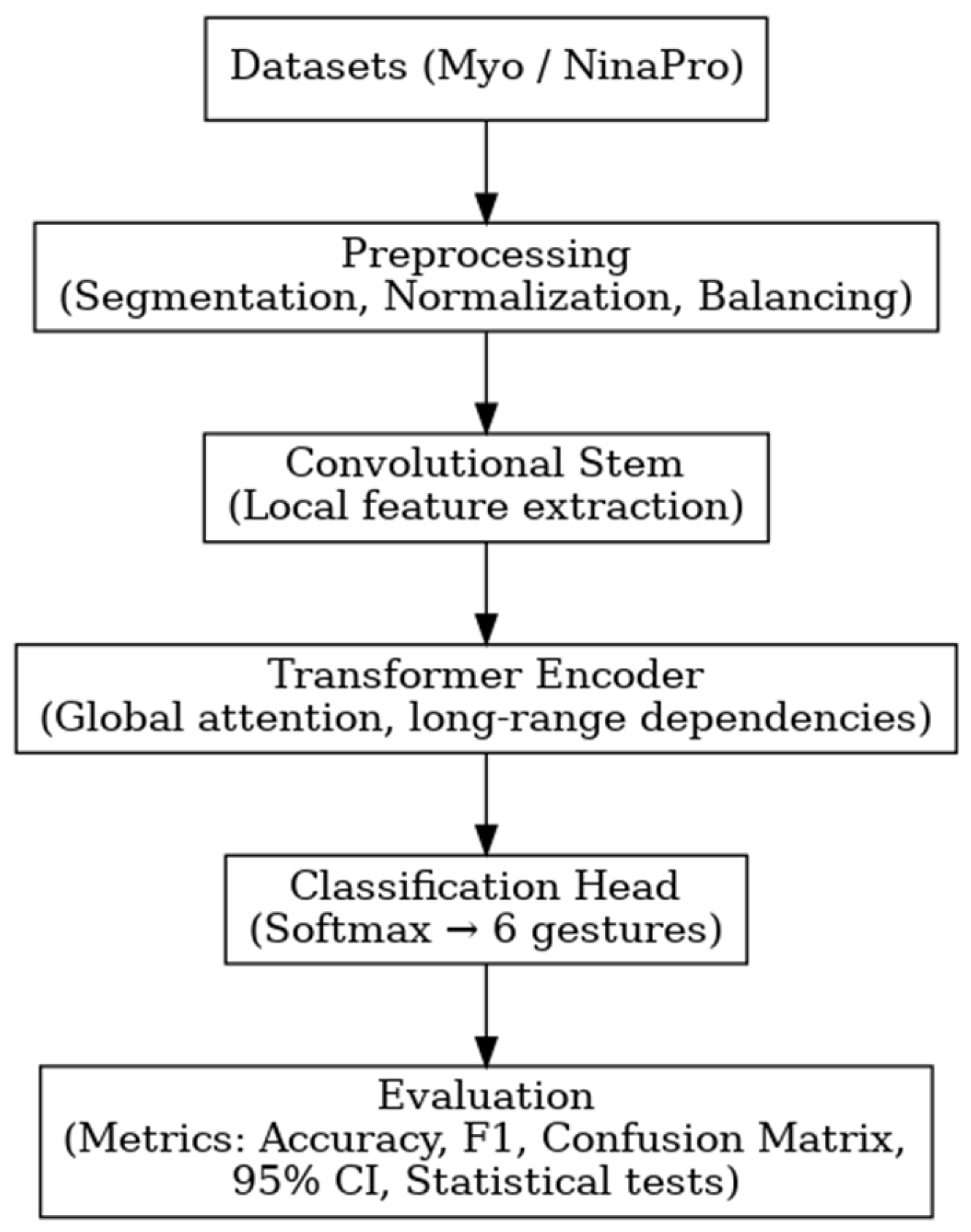

For the comparative evaluation, two reference architectures were considered: a CNN previously employed in the literature for myoelectric signal analysis (Atzori et al.) and the proposed model based on the Vision Transformer (ViT). Both architectures were trained and validated on two datasets—the proprietary Myo dataset and the public NinaPro DB3 dataset, allowing analysis of their behavior under different levels of subject variability and acquisition conditions. This section presents the obtained results, organized as global per-subject metrics and subsequently illustrated through confusion matrices, providing a comprehensive view of each model’s performance and error patterns.

3.1. Global Performance Metrics

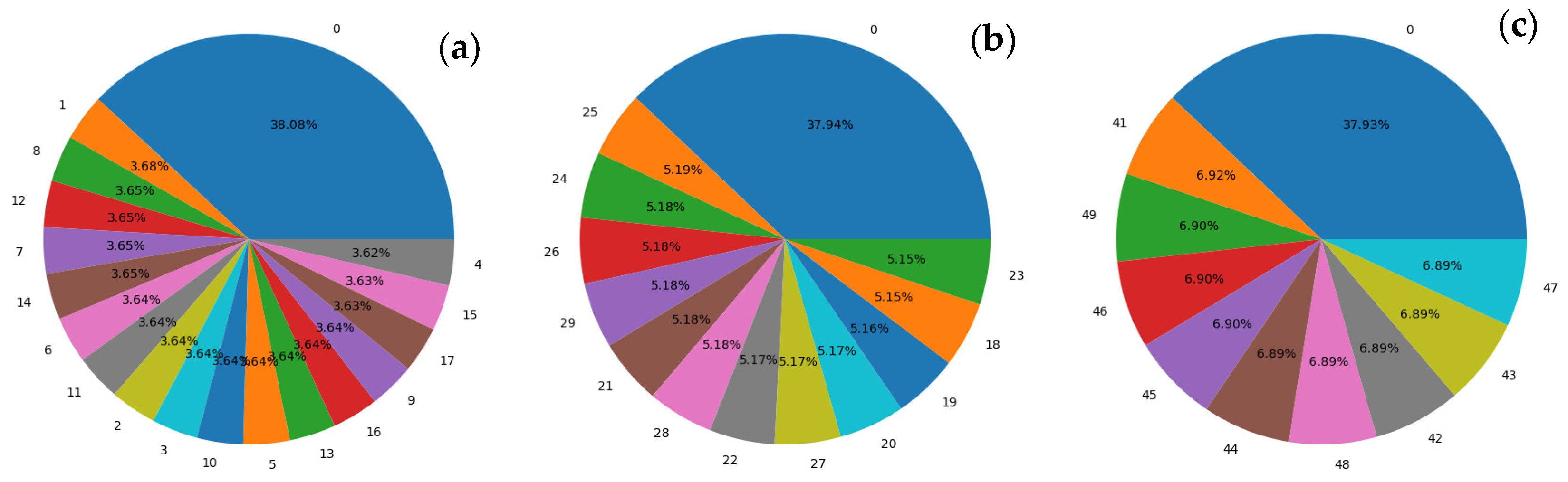

The results obtained on the Myo dataset (see

Table 7) show high and stable performance of the CNN across most subjects: Accuracy, Macro-Precision, Macro-Recall, and Macro-F1 range between 0.95 and 0.98 for eight out of ten participants, with very narrow 95% confidence intervals (even null for P1, P5, P8, and P10), suggesting low variability across repetitions and consistent classifier behavior. Notably, P4 achieved the highest performance (0.980), while P7 also performed strongly (0.965 ± 0.0052), demonstrating solid model generalization. The fact that all four metrics are nearly identical indicates a good balance among classes (similar precision and recall values) and the absence of marked biases toward majority gestures.

The exceptions are concentrated in P3 (≈0.885), P6 (≈0.913 ± 0.0073), and P9 (≈0.899 ± 0.0036), where a systematic performance drop and non-zero confidence intervals are observed—patterns consistent with greater intra-subject heterogeneity, less stable muscle contractions, or gesture overlap. These three cases account for the overall dispersion and suggest specific avenues for improvement: (i) rebalancing or cleaning problematic signal segments, (ii) increasing data for confusing gestures, (iii) applying temporal regularization or augmentation (e.g., jitter, mild warping), and (iv) incorporating multiscale temporal blocks or lightweight attention mechanisms to better capture sEMG variations.

A methodological nuance: the 95% confidence intervals were computed over n = 14 runs per subject; if these partitions are not entirely independent, the CIs may be slightly optimistic. Nevertheless, the consistency observed in P1, P5, P8, and P10 (SD ≈ 0) reinforces that the model remains stable when the signals are more regular.

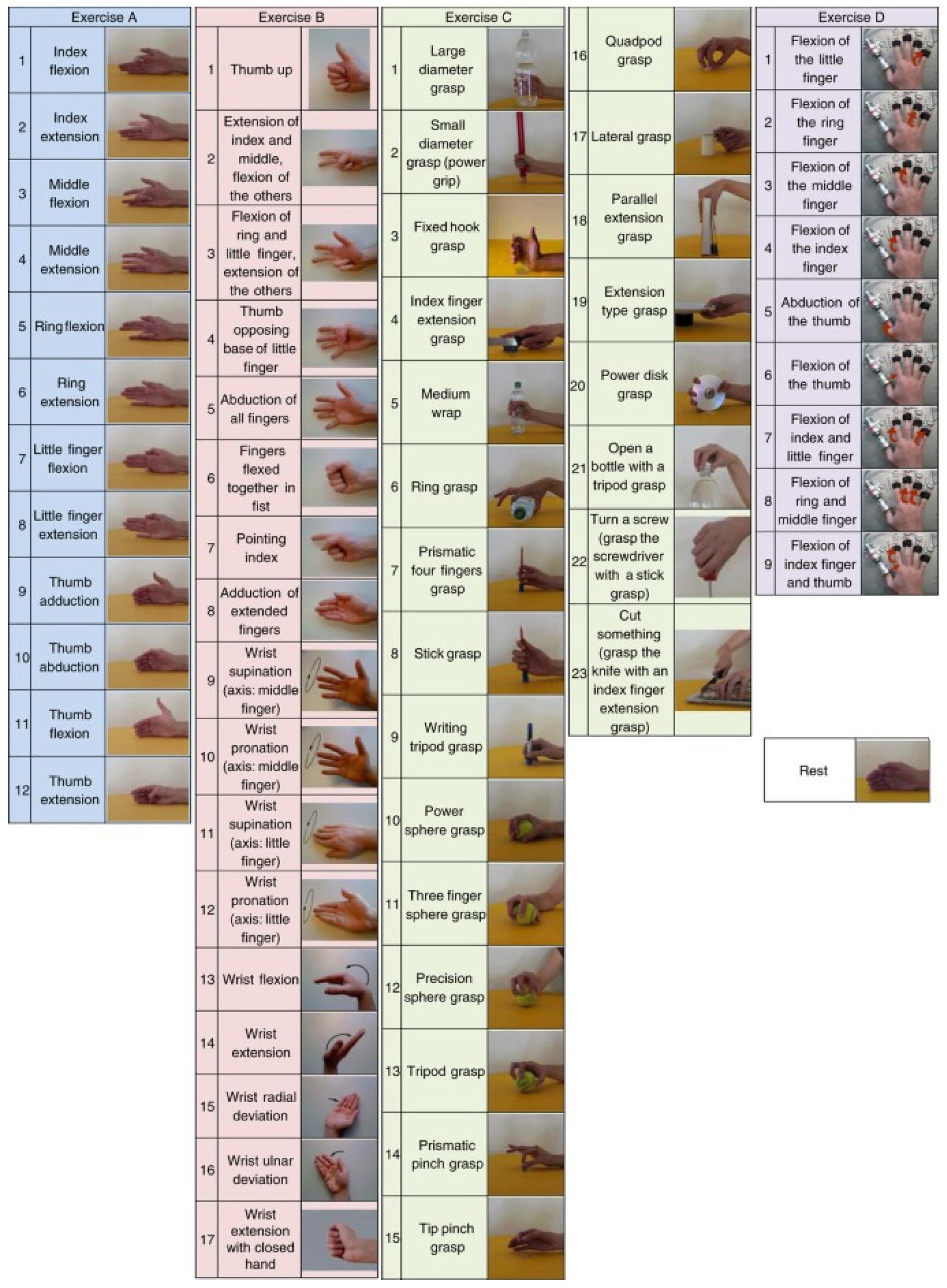

The evaluation of the CNN architecture on the public NinaPro DB3 dataset (

Table 8) reveals a markedly more heterogeneous performance compared to the proprietary Myo dataset, reflecting the greater clinical complexity and variability among amputee subjects included in this collection. Overall, patients A1, A6, A9, and A11 achieved the best performance, with accuracy values close to 0.96 and equally high macro-F1 and macro-recall metrics, indicating that the CNN maintains consistent classification capability in subjects with good residual muscle activity and clean signal acquisition.

However, several cases exhibit considerably lower results, confirming the high inter-subject variability inherent to NinaPro DB3. Patient A3 reached an accuracy of 0.718 ± 0.024, with a 95% confidence interval of ±0.016, indicating substantial dispersion in gesture recognition performance. More critically, Patient A7 recorded an average accuracy of 0.344 ± 0.011 (±0.0062), representing an outlier within the dataset. According to NinaPro DB3’s clinical metadata, this subject has 0% of residual forearm, implying the complete absence of muscle tissue suitable for electrode placement to capture useful electromyographic signals [

25]. This extreme anatomical condition explains the inability to obtain coherent myosensorial patterns, resulting in the CNN’s failure to extract discriminative features effectively.

The contrast between high-performing patients (A1, A6, A9, A11) and low-performing ones (A3 and A7) highlights the model’s sensitivity to physiological and experimental heterogeneity. Variations in electrode placement, contraction intensity, muscle fatigue, or signal noise directly affect prediction stability. Consequently, these findings emphasize the need for more robust normalization strategies, personalized calibration, or adaptive approaches (e.g., hybrid or attention-based models) that can compensate for individual variability and improve model generalization in real clinical contexts.

The performance of the CViT model on the Myo dataset (see

Table 9) is consistently high in test accuracy, ranging approximately from 0.858 to 0.995. Notable results include P4 (0.995 ± 0.0039), P10 (0.987 ± 0.0045), P7 (0.986 ± 0.0037), and P5 (0.983 ± 0.0039), all exhibiting low standard deviations and narrow confidence intervals, which indicate inter-repetition stability and strong intra-subject generalization. At the lower end, P3 (0.858 ± 0.0080) shows the lowest performance and the greatest relative dispersion within the cohort, suggesting greater difficulty in gesture separability for that subject.

In terms of macro-metrics, the expected pattern is observed: Macro-Precision and Macro-F1 tend to be slightly lower than Accuracy (e.g., P1: Acc 0.949 vs. F1-macro 0.921), reflecting that although the model achieves a high overall success rate, class balance is not entirely perfect. Macro-Recall is, on average, the most demanding metric (e.g., P1: 0.901; P10: 0.940), indicating that some classes still exhibit higher false-negative rates (gestures the model “fails to detect”). The 95% confidence intervals for the macro-metrics are moderately wider in some subjects (e.g., Recall in P3: ±0.0092), suggesting session-to-session or gesture-specific variability in certain classes.

Physiological/Methodological Interpretation: Inter-subject differences may be associated with variability in electrode placement, muscle activation level, fatigue, and consistency in gesture execution. The strong performance of P4, P7, and P10, along with their narrow confidence intervals, suggests signals with higher signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) or more consistent gesture patterns. In contrast, P3 likely exhibits lower class separability or increased noise and artifacts, which particularly penalize Recall performance.

The performance of the CViT model on the NinaPro DB3 dataset (see

Table 10) is high and stable for most subjects: test accuracy values, with few exceptions, range between 0.960 and 0.983 (e.g., A5 = 0.983 ± 0.0040, A11 = 0.982 ± 0.0051, A1 = 0.977 ± 0.0050, A4 = 0.975 ± 0.0033, A10 = 0.971 ± 0.0044, A2/A3 ≈ 0.970), with narrow standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals (typically ≤ 0.005–0.015 and ≤0.003–0.009, respectively). This indicates inter-repetition consistency and strong intra-subject generalization capability, even in a heterogeneous setting such as DB3.

In the macro-metrics, the usual pattern is observed: Macro-F1 and Macro-Precision are slightly lower than Accuracy (e.g., A1: Acc 0.977 vs. F1-macro 0.962; A4: Acc 0.975 vs. F1-macro 0.942), indicating that although overall performance is high, not all classes contribute equally. Macro-Recall tends to be the most demanding metric for some subjects (e.g., A6 = 0.911 ± 0.0109 (±0.0058), A9 = 0.905 ± 0.0144 (±0.0077), A8 = 0.930 ± 0.0112 (±0.0060)), revealing false negatives concentrated in difficult or underrepresented gestures. Nevertheless, the 95% confidence intervals remain moderate, suggesting controlled variability across repetitions.

The best performances correspond to A5, A11, and A1, which combine high accuracy with elevated Macro-F1 and Macro-Precision values (A5: F1-macro 0.962; A11: 0.954; A1: 0.962), reflecting signals with good signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), consistent execution, and more separable gesture classes within the CViT feature space. In contrast, A9 (Acc 0.914; F1-macro 0.894) and especially A7 (Acc 0.663; F1-macro 0.657) represent the lower-performance cases. Patient A7 exhibits a clear and homogeneous deterioration across all metrics, consistent with the clinical metadata reported for DB3 (0% residual forearm). In practice, the absence of usable muscle tissue prevents the capture of discriminative EMG activity, which compromises inter-gesture separability and substantially reduces Recall and Macro-F1. This case illustrates the physiological limit of conventional non-adaptive approaches.

3.2. Per-Class Performance and Confusion Matrices

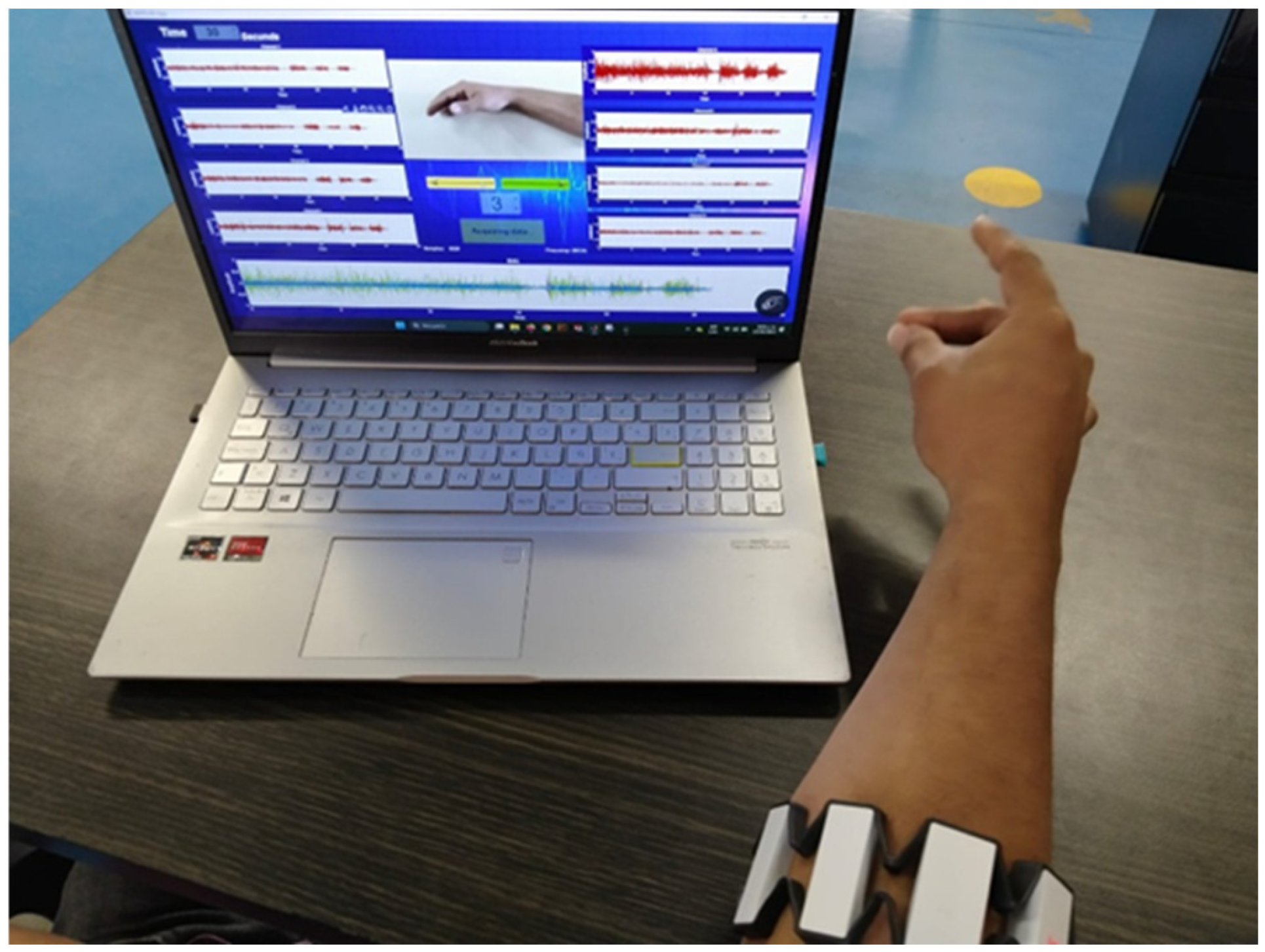

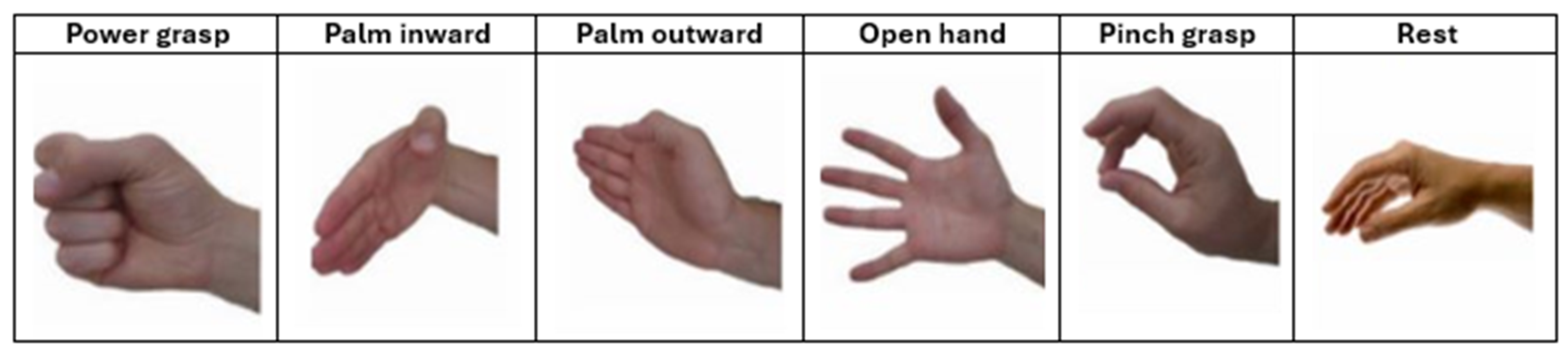

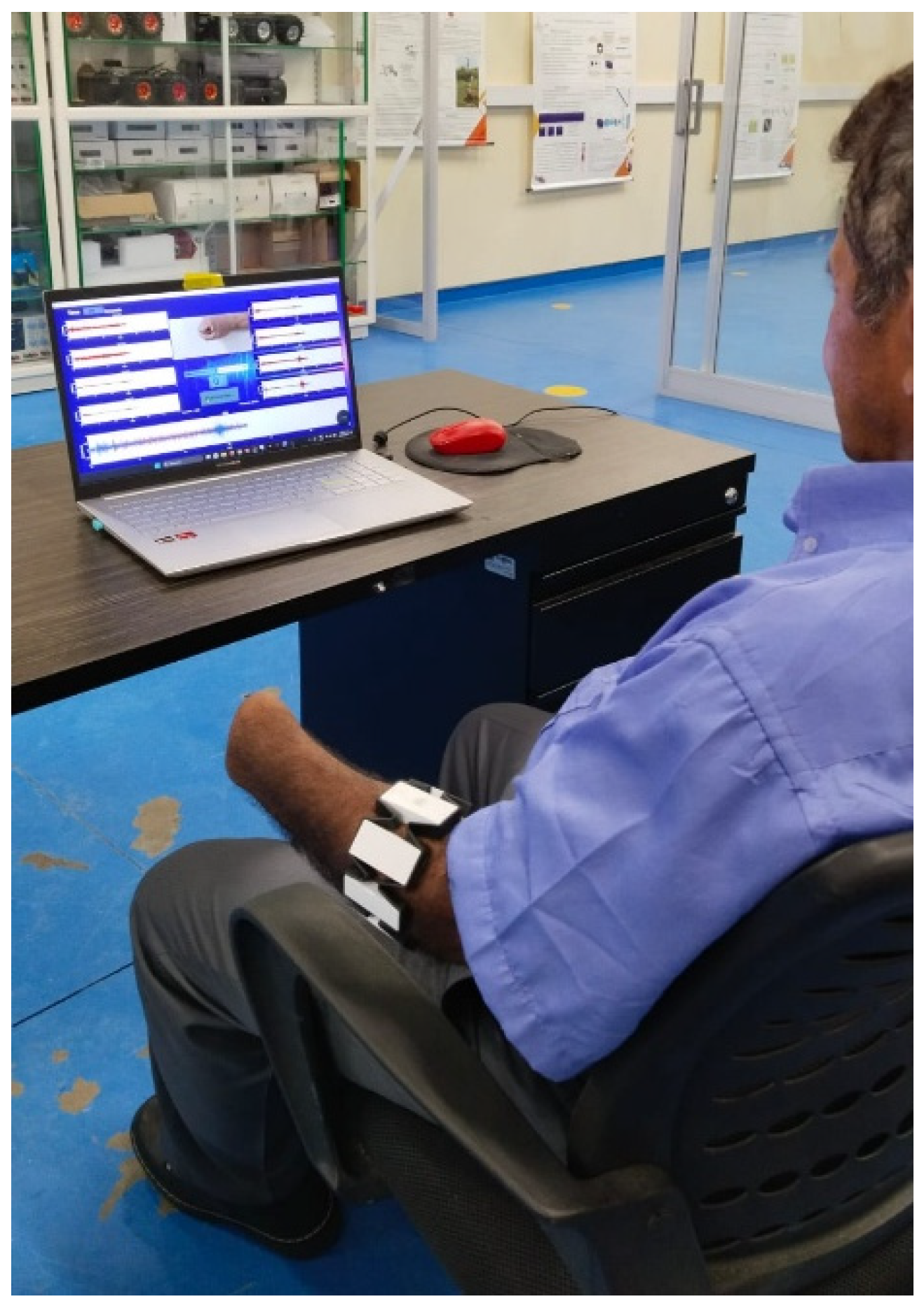

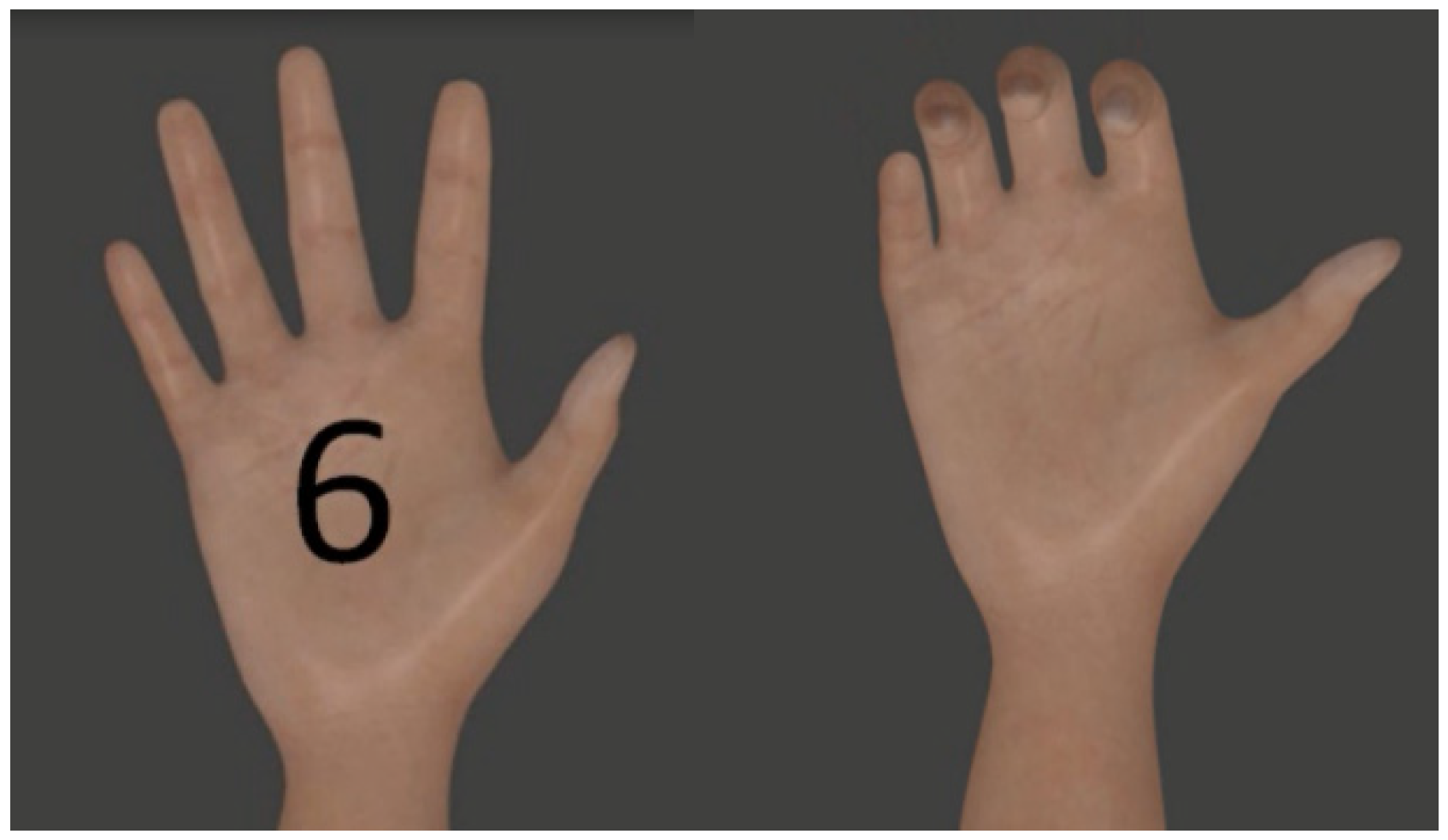

To complement the global metrics presented above, confusion matrices were employed to visually illustrate the model’s performance in classifying the different gestures. Each matrix summarizes the relationship between the true labels and the model’s predictions, where the main diagonal represents correct classifications and the off-diagonal values reflect gesture confusions. Two contrasting scenarios from the Myo dataset are included as examples: one patient with outstanding performance and another with intermediate performance. This comparison highlights both the model’s ability to accurately discriminate gestures and the challenges that may arise in subjects exhibiting greater variability in electromyographic signals.

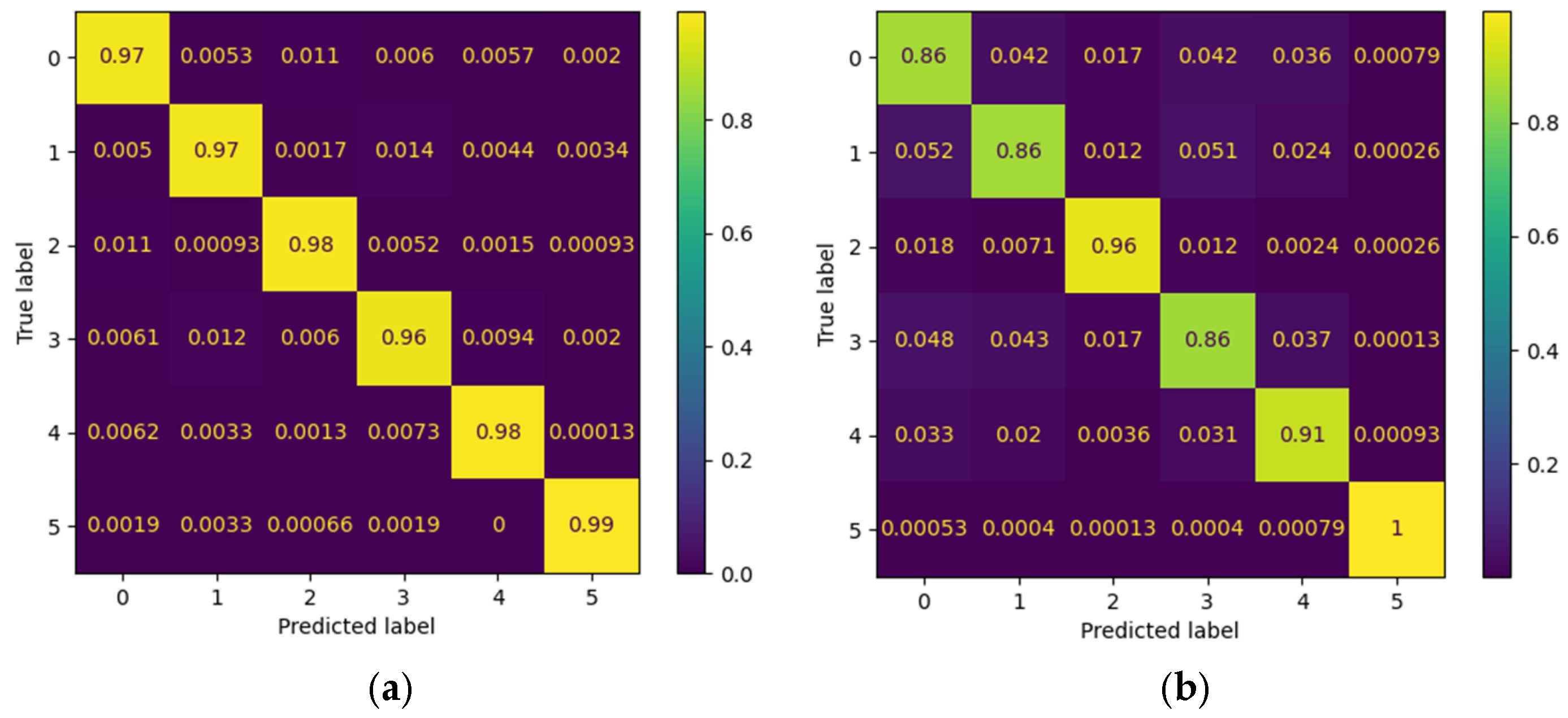

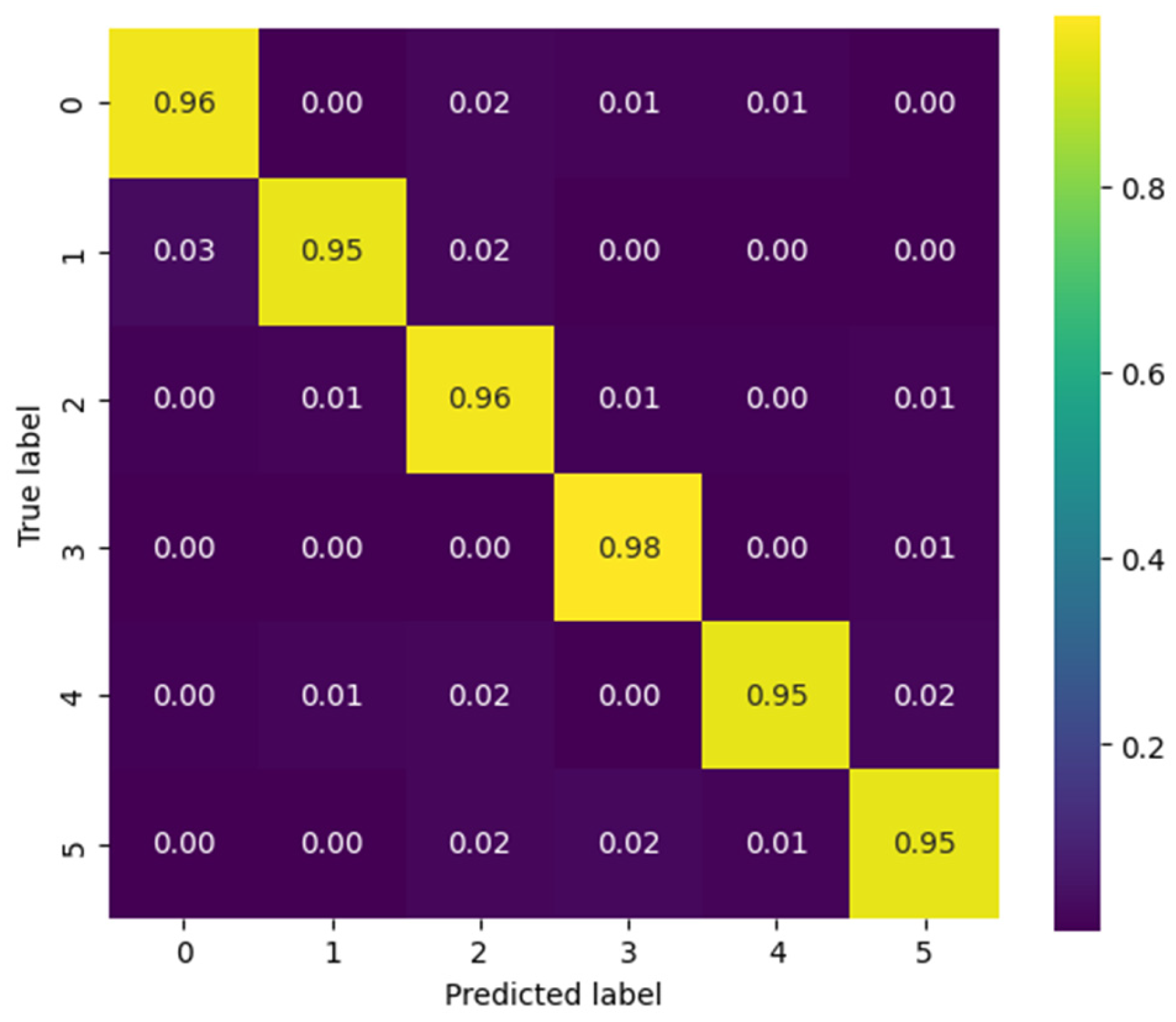

Figure 12 presents the confusion matrices corresponding to the CNN model applied to the Myo dataset, using the following gesture classes: 0—Rest (RE), 1—Power Grip (AP), 2—Palm Inward (PI), 3—Palm Outward (PO), 4—Open Hand (MO), and 5—Pinch Grip (AT). For Patient 4, the diagonal values range between 0.96 and 0.99, indicating highly accurate recognition across nearly all classes, with minimal confusion between Palm Outward (3–PO) and Pinch Grip (5–AT). In contrast, the matrix for patient 8 reflects an intermediate performance: although high diagonal values are maintained (≈0.86–0.96), more classification errors are observed—particularly between Rest (0–RE) and Power Grip (1–AP), as well as between Palm Outward (3–PO) and Open Hand (4–MO). These differences highlight how individual variability in myoelectric signals can significantly influence classifier performance.

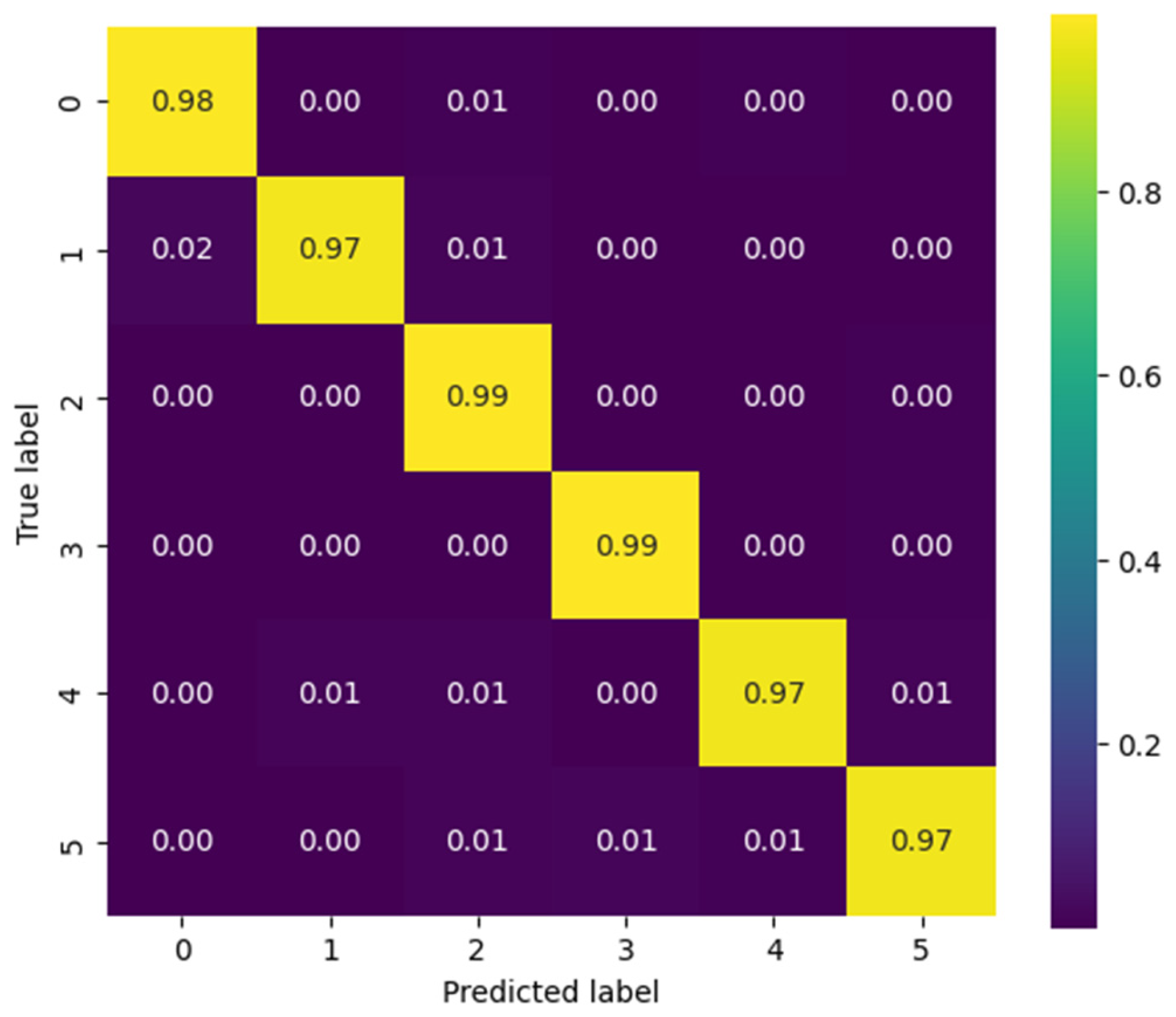

Figure 13 presents the confusion matrices corresponding to two representative patients from the public NinaPro DB3 dataset, evaluated using the CNN model. The first matrix corresponds to patient 3, who exhibits intermediate performance with notable confusions among similar classes, while the second corresponds to patient 6, who demonstrates outstanding performance with near-perfect predictions across all classes.

In the case of patient 3, the network correctly recognizes most instances of the “Rest (0)” and “Open Hand (MO, 3)” classes, with values near the main diagonal (1.00 and 0.98, respectively). However, notable confusions are observed among gestures such as “Palm Outward (PO, 2),” which achieves a 0.67 accuracy, and other classes like “Palm Inward (PI, 1)” and “Pinch Grip (AT, 4),” indicating difficulty in discriminating gestures with similar postural configurations. Likewise, the “Rest (0)” class was detected with complete accuracy, confirming the model’s robustness in distinguishing the absence of movement.

In contrast, the confusion matrix for patient 6 illustrates an almost ideal classification scenario. All classes exhibit diagonal values close to 1.00, with a maximum of 0.99 in the “Open Hand (MO, 3)” class. The absence of significant off-diagonal values demonstrates the model’s high generalization capability for this subject, with no relevant gesture confusions.

This contrast between the two matrices highlights the inter-subject variability characteristic of myoelectric data, where some users produce more consistent and well-separated signals across classes, while others exhibit overlaps that increase classifier confusion.

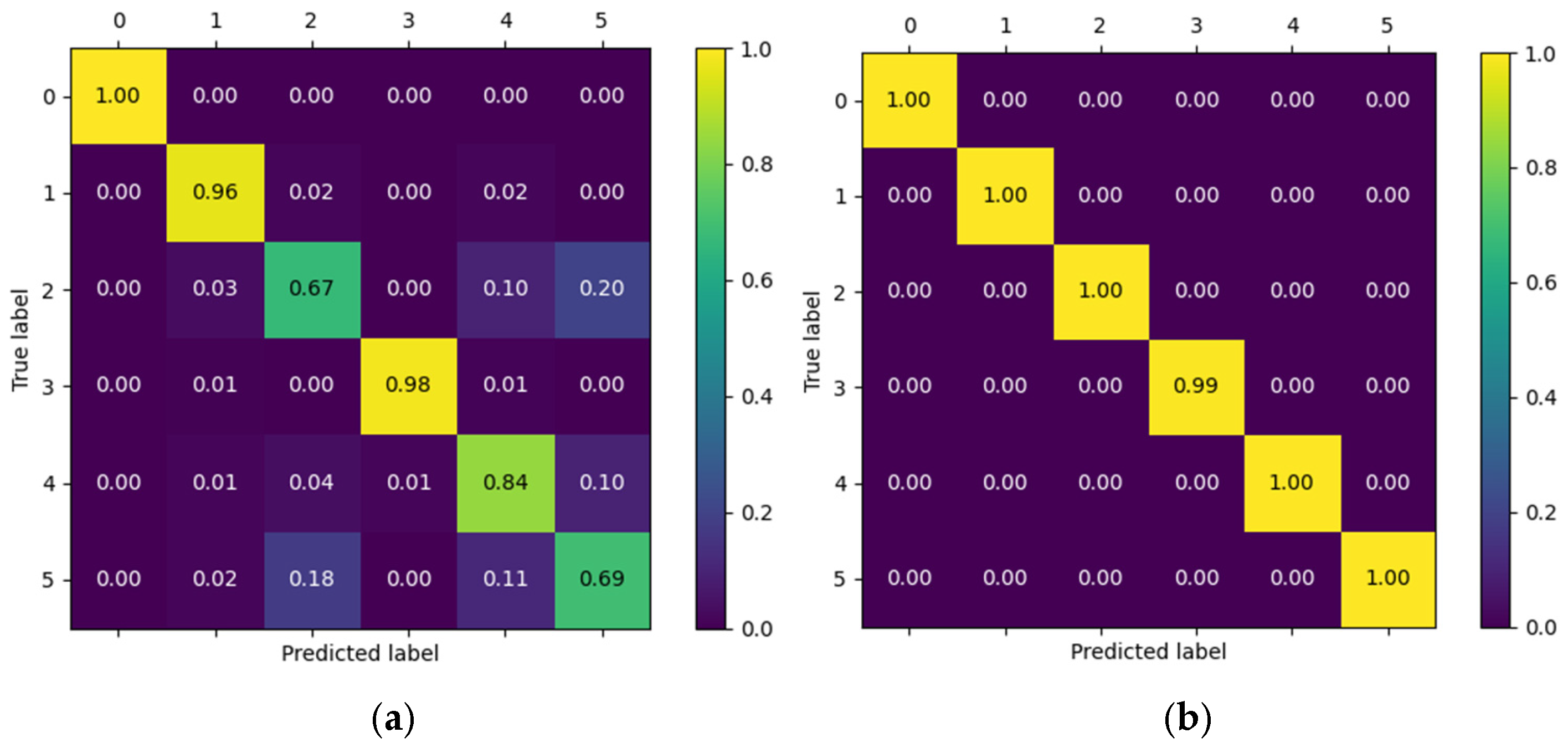

Figure 14 presents the confusion matrix corresponding to patient 3, evaluated using the CViT model on the Myo dataset. High performance is observed across most classes, with correct prediction values near 0.95–0.98 along the main diagonal, reflecting the model’s strong generalization capability. However, certain confusions are identified among gestures with similar biomechanics—such as between Palm Outward (PO, class 4) and Pinch Grip (AT, class 5), as well as between Palm Inward (PI, class 1) and Rest (RE, class 0). These misclassifications are consistent with the biomechanical similarity of these movements, a common challenge in EMG signal classification tasks. Despite these localized difficulties, the overall results demonstrate that CViT effectively discriminates the main gestures in the Myo dataset, confirming its robustness as an alternative to conventional convolutional architectures.

Figure 15, corresponding to the CViT model trained on the NinaPro DB3 dataset, shows highly consistent performance in the classification of the six gesture classes: Rest (0), Power Grip (1), Palm Inward (2), Palm Outward (3), Open Hand (4), and Pinch Grip (5). The values along the main diagonal reach accuracies close to or above 0.97 for all classes, reflecting the model’s strong discriminative capability. Off-diagonal confusions are minimal and uniformly distributed, with no dominant error pattern toward any particular class. This result confirms the CViT model’s ability to generalize effectively even in a more complex and heterogeneous dataset such as NinaPro DB3, highlighting its potential for practical applications in myoelectric gesture recognition.

3.3. Statistical Comparisons

The results of the statistical evaluation are presented in

Table 11. For the Myo dataset, both the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test (W = 8.0,

p = 0.049) and the paired Student’s

t-test (t = −2.36,

p = 0.043, n = 10) revealed statistically significant differences between the models, indicating a systematic advantage of CViT over CNN. The negative sign of the t statistic confirms that the mean difference favors CViT, reinforcing the conclusion that this architecture is more effective for classifying signals in the Myo dataset. Furthermore, the magnitude of the difference can be considered medium-to-high, which lends practical relevance to the finding beyond its statistical significance.

In contrast, no significant differences were observed between CNN and CViT in the NinaPro DB3 dataset. Both the Wilcoxon test (W = 21.0, p = 0.320) and the paired t-test (t = −1.33, p = 0.213, n = 11) failed to reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the two models exhibit statistically equivalent performance on this dataset. Although the statistics suggest a slight trend in favor of CViT, inter-subject variability and the limited sample size constrain the statistical power to detect small effects. This outcome reflects the greater complexity and heterogeneity of NinaPro, where algorithmic differences tend to be attenuated.

Finally, the Friedman test applied to the four experimental scenarios (CNN-Myo, CViT-Myo, CNN-NinaPro, and CViT-NinaPro) did not reveal any significant differences . This result confirms that, overall, the models exhibit comparable performance when all contexts are considered jointly. The absence of global significance implies that the advantages observed in the Myo dataset are not consistently reproduced in other scenarios, thereby diluting their impact at the aggregate level.

In addition to the statistical significance values,

Table 12 presents the effect sizes associated with each comparison. In the Myo dataset, the effect size computed using Cohen’s d was 0.75, corresponding to a medium-to-large magnitude, while the Wilcoxon r coefficient reached −0.63, considered a large effect. These results indicate that, beyond statistical significance (

p < 0.05), the observed difference between CNN and CViT in this dataset is of practical relevance, reflecting a substantial performance advantage of the CViT model.

In contrast, in the NinaPro dataset, the effect sizes were smaller: Cohen’s d = 0.40 and r = −0.32, corresponding to small-to-medium magnitudes. These values are consistent with the absence of statistical significance (p > 0.05), suggesting that although there is a slight trend in favor of CViT, the magnitude of the difference is not sufficient to be considered practically relevant.

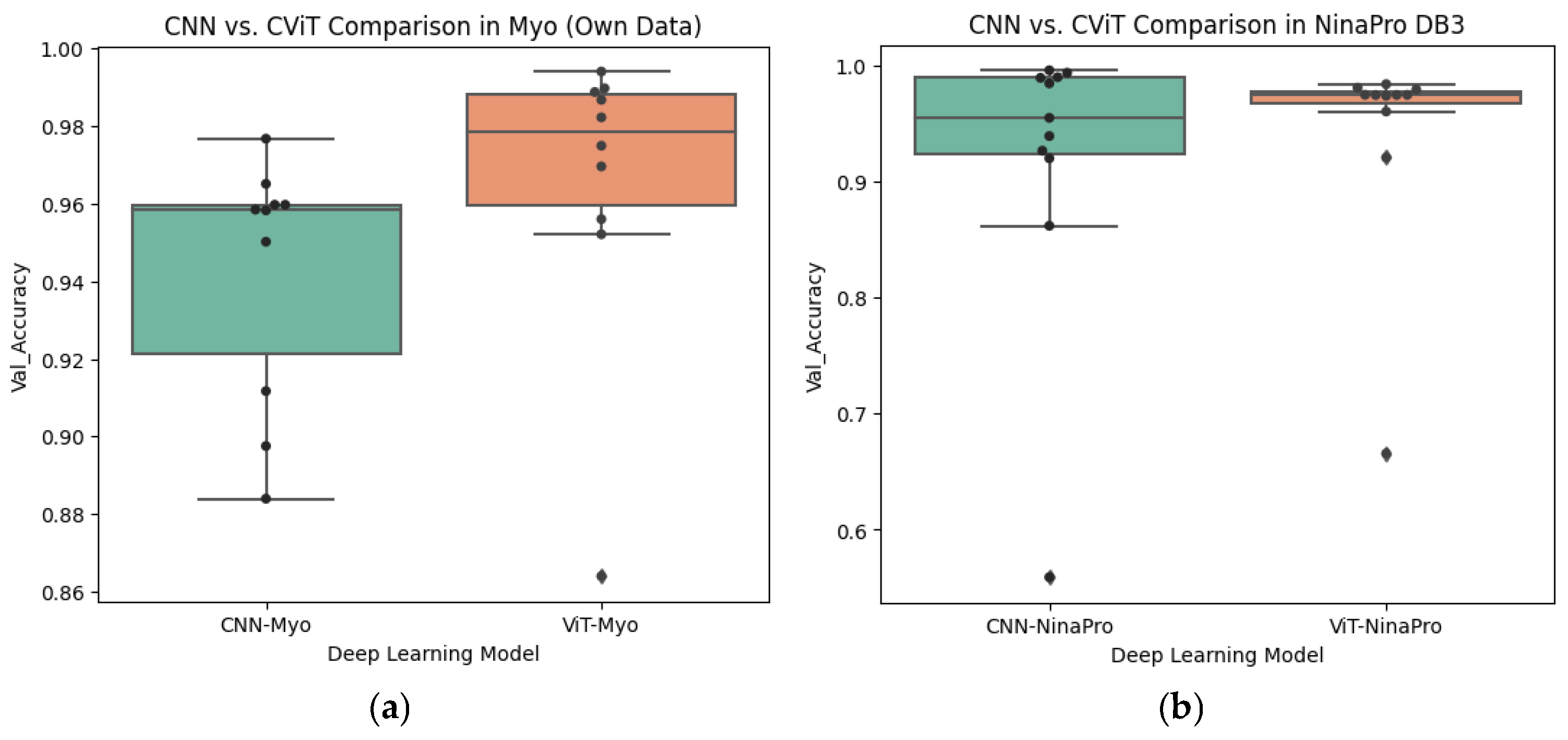

In

Figure 16a, it can be observed that within the Myo dataset, the CViT architecture consistently achieves higher values than the CNN, with a higher median and lower dispersion. The individual patient results (black dots) reinforce the trend of CViT outperforming CNN, which aligns with the statistically significant differences identified in the hypothesis tests and the medium-to-large effect sizes.

To control for potential inflation of Type I error arising from multiple pairwise comparisons, Bonferroni correction was applied to all

p-values obtained from Wilcoxon and paired

t-tests. Considering four simultaneous comparisons, the adjusted threshold was α_adj = 0.05/4 = 0.0125 (See

Table 13). Under this correction, none of the differences between CNN and CViT remained statistically significant (adjusted

p-values: Myo–Wilcoxon = 0.196, Myo–

t-test = 0.172, NinaPro–Wilcoxon = 1.0, NinaPro–

t-test = 0.852). Nevertheless, the CViT consistently achieved higher accuracy across all experimental configurations, supporting a performance advantage despite the conservative statistical adjustment.

In contrast,

Figure 16b shows that, within the NinaPro dataset, the distributions of CNN and CViT overlap considerably. Although there is a slight trend suggesting that CViT achieves higher values, inter-subject variability and the presence of outliers reduce the magnitude of this difference. This observation aligns with the absence of statistical significance and the small-to-medium effect sizes reported in

Table 11.