Design and Characterization of Sustainable PLA-Based Systems Modified with a Rosin-Derived Resin: Structure–Property Relationships and Functional Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Blends Compounding and Sample Preparation

2.3. Thermal Characterization of PLA Blends with UP Resin

2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

2.5. Mechanical Properties

2.6. Rotational Rheology

2.7. Morphological Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

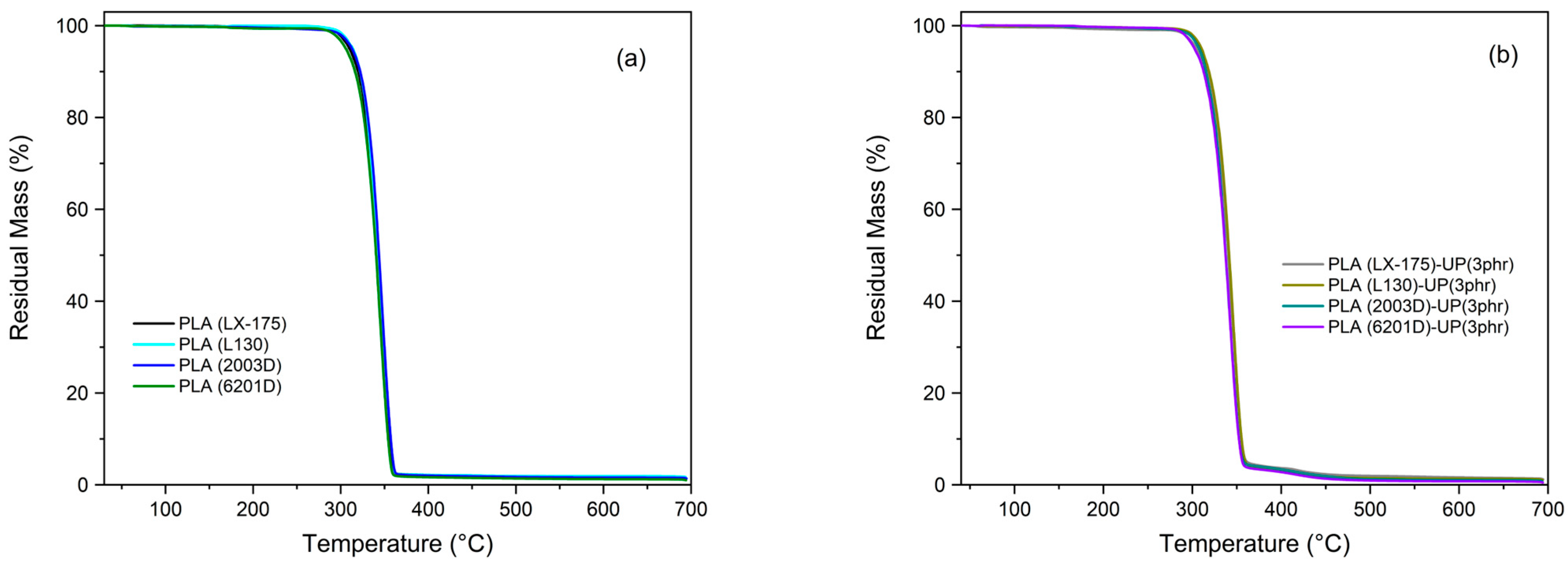

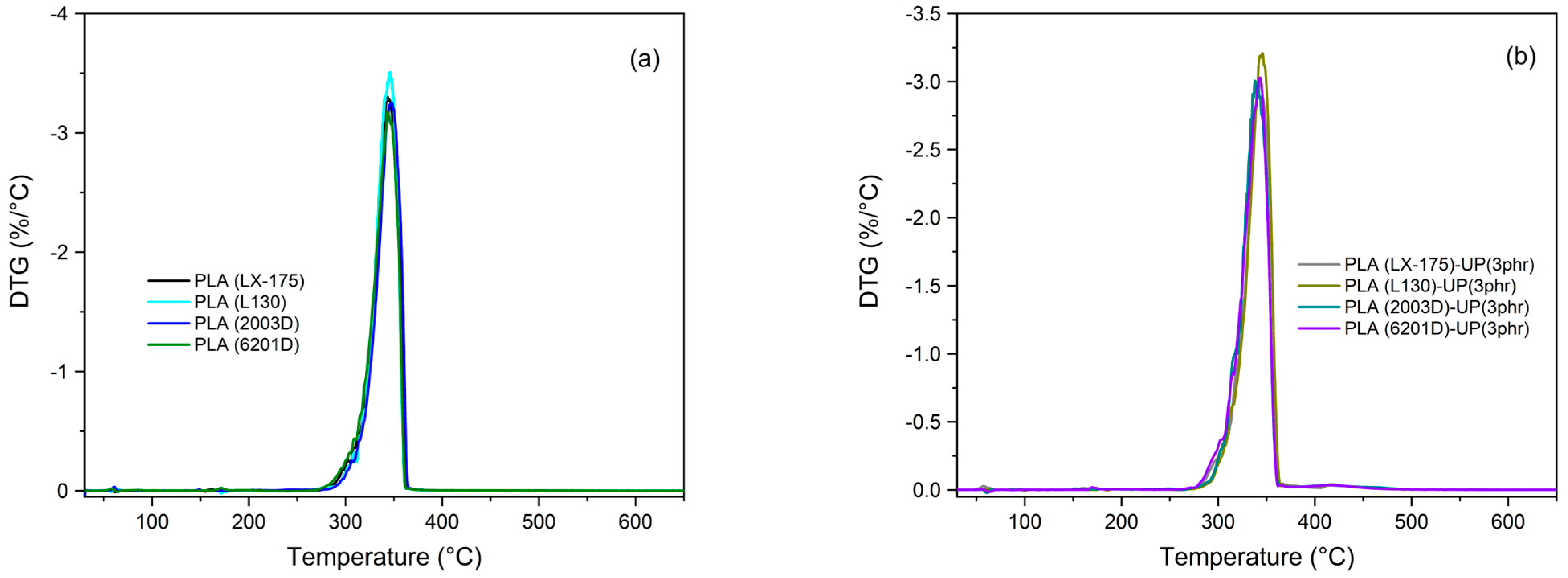

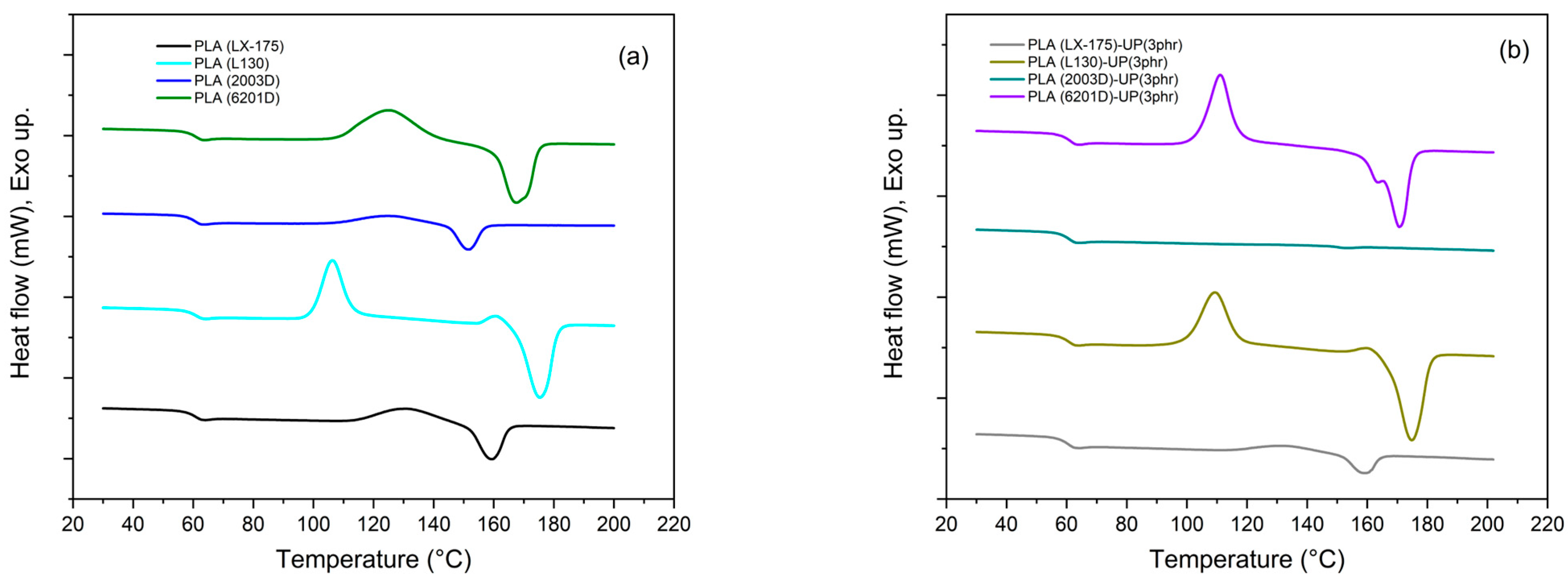

3.1. Thermal Behavior of TPS/PVA Materials

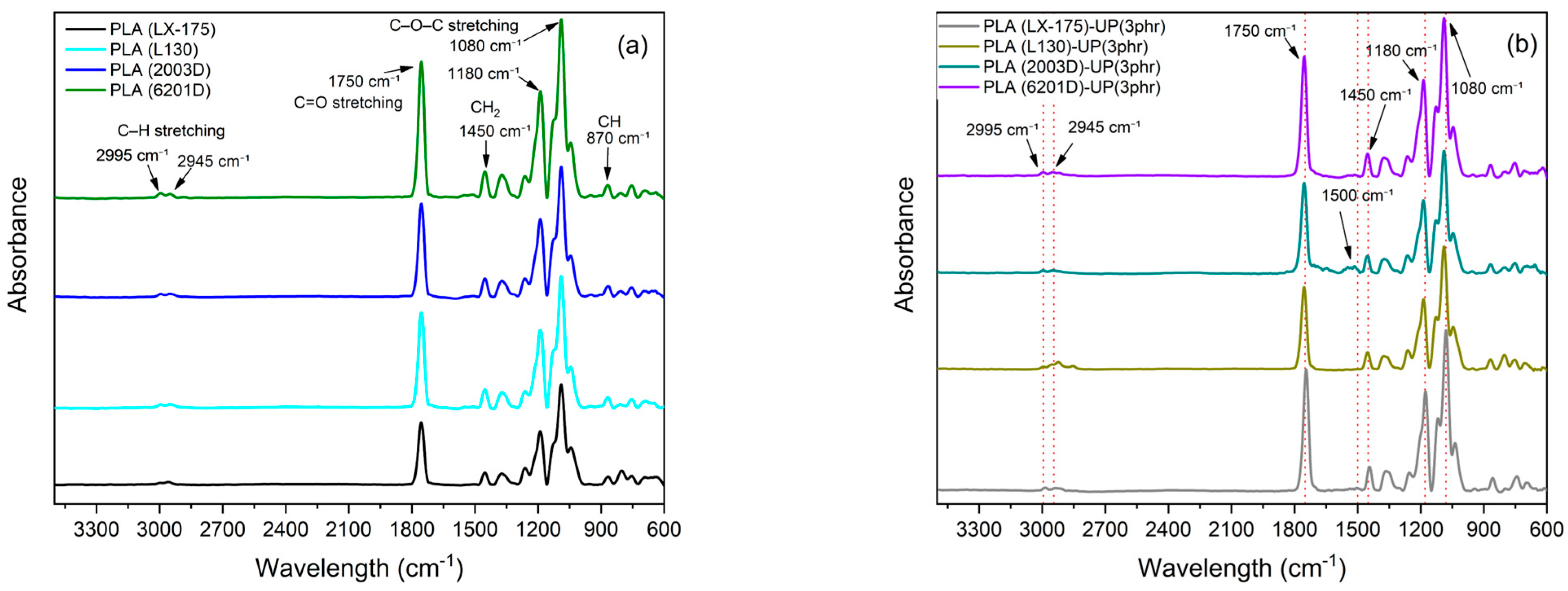

3.2. FTIR Analysis of TPS/PVA Blend

3.3. Mechanical Performance of TPS/PVA Blends

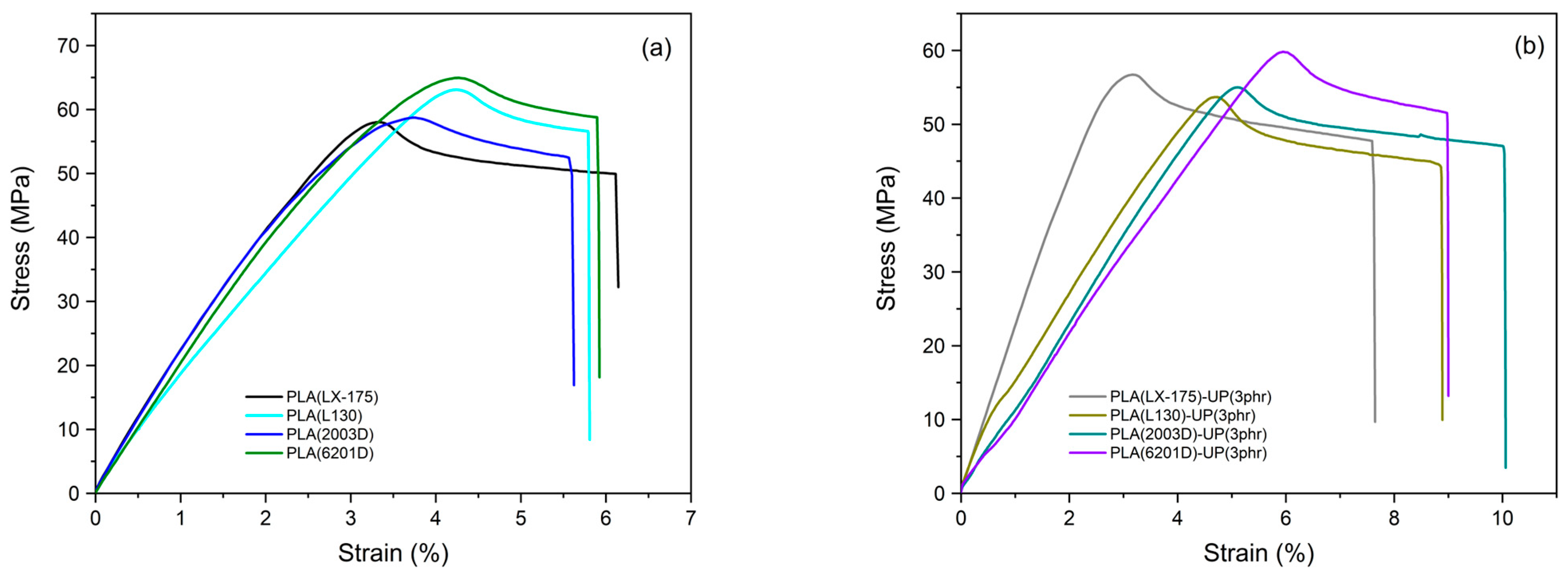

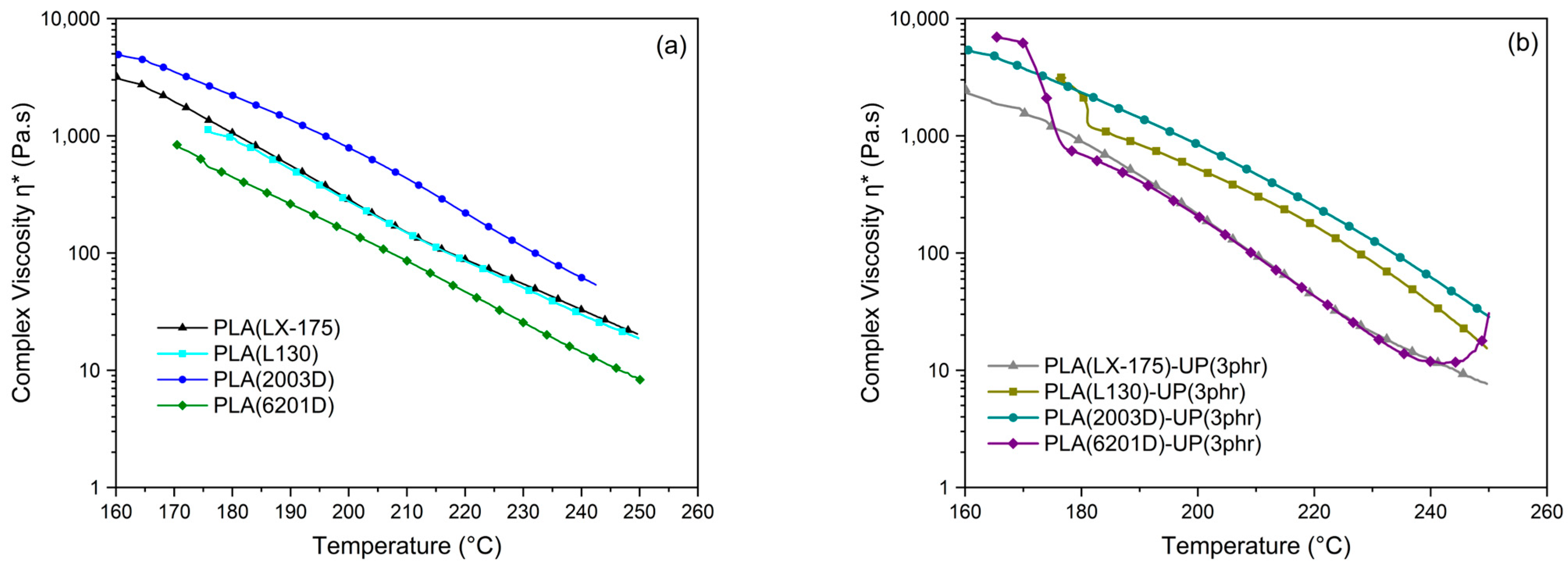

3.4. Dynamic Rheological Analysis

3.5. Microstructural Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLA | Poly(lactic acid) |

| UP | Phenol-free modified rosin resin (Unik Print™ 3340) |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| DTG | Derivative Thermogravimetry |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| Tg | Glass Transition Temperature |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

| Tcc | Cold Crystallization Temperature |

| T5% | Onset Degradation Temperature (at 5% weight loss) |

| Tmax | Maximum Degradation Temperature |

| ΔHm | Melting Enthalpy |

| ΔHcc | Cold Crystallization Enthalpy |

| Xc | Degree of Crystallinity |

| FESEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| phr | Parts per Hundred of Resin (by weight) |

| Mw | Molecular Weight |

| L/D | Length-to-Diameter Ratio (of the extruder) |

| MFR | Melt Flow Rate |

| DMA | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis |

| UPR | Unsaturated Polyester Resin (general abbreviation, for comparison) |

References

- Nanda, S.; Patra, B.R.; Patel, R.; Bakos, J.; Dalai, A.K. Innovations in applications and prospects of bioplastics and biopolymers: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 20, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, P.I.C.; Neto, A.R.S.; Bibbo, A.C.C.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Bastos, M.S.R.; Marconcini, J.M. Biodegradable blends with potential use in packaging: A comparison of PLA/chitosan and PLA/cellulose acetate films. J. Polym. Environ. 2016, 24, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa-Ramírez, H.; Aldas, M.; Ferri, J.M.; López-Martínez, J.; Samper, M.D. Modification of poly(lactic acid) through the incorporation of gum rosin and gum rosin derivative: Mechanical performance and hydrophobicity. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruchelvi, R.; Das, A.; Sikdar, E. Bioplastics as better alternative to petro plastic. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 37, 1634–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, M.S.; Zinjarde, S.S.; Gokhale, D.V. Polylactic acid: Synthesis and biomedical applications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Hernández, B.; Lieske, A. Widening the application range of PLA-based thermoplastic materials through the synthesis of PLA-polyether block copolymers: Thermal, tensile, and rheological properties. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2024, 309, 2300309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virág, Á.D.; Tóth, C.; Polyák, P.; Musioł, M.; Molnár, K. Tailoring the mechanical and rheological properties of poly(lactic acid) by sterilizing UV-C irradiation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; Samper, M.D.; Jiménez-López, M.; Aldas, M.; López, J. Combined effect of linseed oil and gum rosin as natural additives for PVC. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 99, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlberg, A.T.; Hagvall, L. Colophony: Rosin in unmodified and modified form. In Kanerva’s Occupational Dermatology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.B.; Jin, M.Y.; Oh, S.S.; Ryu, D.H. Synthesis of an environmentally friendly phenol-free resin for printing ink. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2012, 33, 3413–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, C. Recent advancements in bio-based plasticizers for polylactic acid (PLA): A review. Polym. Test. 2024, 140, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavon, C.; Aldas, M.; López-Martínez, J.; Ferrándiz, S. New materials for 3D printing based on polycaprolactone with gum rosin and beeswax as additives. Polymers 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldas, M.; Pavon, C.; López-Martínez, J.; Arrieta, M.P.P. Pine resin derivatives as sustainable additives to improve the mechanical and thermal properties of injected moulded thermoplastic starch. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2561–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa-Ramírez, H.; Dominici, F.; Ferri, J.M.; Luzi, F.; Puglia, D.; Torre, L.; López-Martínez, J.; Samper, M.D. Pentaerythritol and glycerol esters derived from gum rosin as bio-based additives for the improvement of processability and thermal stability of polylactic acid. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 5446–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, E.; Akkoyun Kurtlu, M. Impact of production methods on properties of natural rosin added polylactic acid/sodium pentaborate and polylactic acid/calcium carbonate films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265, 130965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa-Ramírez, H.; Aldas, M.; Ferri, J.M.; Pawlak, F.; López-Martínez, J.; Samper, M.D. Control of biodegradability under composting conditions and physical performance of poly(lactic acid)-based materials modified with phenolic-free rosin resin. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 5462–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamadiala, I.; Croitoru, C.; Pop, M.A.; Roata, I.C. Enhancing polylactic acid (PLA) performance: A review of additives in fused deposition modelling (FDM) filaments. Polymers 2025, 17, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, R.; Ray, S.S. Role of rheology in morphology development and advanced processing of thermoplastic polymer materials: A review. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 27969–28001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, F.; García, D.G.; Fombuena, V.; Luzi, F.; Puglia, D.; Torre, L.; Balart, R. Bio-polyethylene-based composites reinforced with alkali and palmitoyl chloride-treated coffee silverskin. Molecules 2019, 24, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B.A. Rheology of polymer melts. In The Science and Technology of Flexible Packaging; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bhasney, S.M.; Patwa, R.; Kumar, A.; Katiyar, V. Plasticizing effect of coconut oil on morphological, mechanical, thermal, rheological, barrier, and optical properties of poly(lactic acid): A promising candidate for food packaging. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, M.; Kwolek, S.; Szparaga, G.; Chrzanowski, M.; Krucinska, I. Investigation of the influence of PLA molecular structure on the crystalline forms (α′ and α) and mechanical properties of wet spinning fibres. Polymers 2017, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN ISO 527-2:2012; Plásticos—Determinación de las Propiedades en Tracción—Parte 2: Condiciones de Ensayo Para Plásticos Para Moldeo y Extrusión. Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE): Madrid, Spain, 2012.

- UNE-EN ISO 179-1:2010; Plásticos—Determinación de las Propiedades al Impacto Charpy—Parte 1: Ensayo no Instrumentado. Asociación Española de Normalización (UNE): Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- Palai, B.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. A comparison on biodegradation behaviour of polylactic acid (PLA)-based blown films by incorporating thermoplasticized starch (TPS) and poly(butylene succinate-co-adipate) (PBSA) biopolymer in soil. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 2772–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signori, F.; Coltelli, M.B.; Bronco, S. Thermal degradation of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and their blends upon melt processing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, F.; Pérez, O.S.; Maspoch, M.L. Kinetics of the thermal degradation of poly(lactic acid) and polyamide bioblends. Polymers 2021, 13, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.E.; Bezci, B.; Özdemir, B.; Göksu, Y.A.; Ghanbari, A.; Jalali, A.; Nofar, M. Thermal and environmentally induced degradation behaviors of amorphous and semicrystalline PLAs through rheological analysis. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 3412–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Ishak, W.H.; Rosli, N.A.; Ahmad, I. Influence of amorphous cellulose on mechanical, thermal, and hydrolytic degradation of poly(lactic acid) biocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pölöskei, K.; Csézi, G.; Hajba, S.; Tábi, T. Investigation of the thermoformability of various D-lactide content poly(lactic acid) films by ball burst test. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauliac, D.; Pullammanappallil, P.C.; Ingram, L.O.; Shanmugam, K.T. A combined thermochemical and microbial process for recycling polylactic acid polymer to optically pure L-lactic acid for reuse. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarska, K.; Piorkowska, E.; Bojda, J. The influence of matrix crystallinity, filler grain size and modification on properties of PLA/calcium carbonate composites. Polym. Test. 2017, 62, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perinović Jozić, S.; Jozić, D.; Jakić, J.; Andričić, B. Preparation and characterization of PLA composites with modified magnesium hydroxide obtained from seawater. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 1877–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlotta, D. A literature review of poly(lactic acid). J. Polym. Environ. 2001, 9, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, S.K. Rosin: A naturally derived excipient in drug delivery systems. Polim. Med. 2013, 43, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, L.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Biodegradable polymers as biomaterials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 762–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Ramos, P.; Fernández-Coppel, I.A.; Ruíz-Potosme, N.M.; Martín-Gil, J. Potential of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy for the classification of natural resins. Biol. Eng. Med. Sci. Rep. 2018, 4, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaba, N.F.; Jaafar, M.; Ismail, H. Tensile and morphological properties of nanocrystalline cellulose and nanofibrillated cellulose reinforced PLA bionanocomposites: A review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2021, 61, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofar, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Carreau, P.J. Effect of TPU hard segment content on the rheological and mechanical properties of PLA/TPU blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; George, S.C.; Anil Kumar, S.; Thomas, S. Liquid transport characteristics in polymeric systems. In Transport Properties of Polymeric Membranes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Comyn, J. What are adhesives and sealants and how do they work? In Adhesive Bonding: Science, Technology and Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, R.J.; Robertson, A.; Mallon, P.E.; Thompson, R.L. The impact of plasticizer and degree of hydrolysis on free volume of poly(vinyl alcohol) films. Polymers 2018, 10, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promnil, S.; Numpaisal, P.O.; Ruksakulpiwat, Y. Effect of molecular weight on mechanical properties of electrospun poly(lactic acid) fibers for meniscus tissue engineering scaffold. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 3496–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldas, M.; Ferri, J.M.; López-Martínez, J.; Samper, M.D.; Arrieta, M.P. Effect of pine resin derivatives on the structural, thermal, and mechanical properties of Mater-Bi type bioplastic. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 137, 48236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenek, S.; Fernandes-Nassar, S.; Ducruet, V. Rheology, mechanical properties, and barrier properties of poly(lactic acid). Adv. Polym. Sci. 2018, 279, 303–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, F.; Aldas, M.; López-Martínez, J.; Samper, M.D. Effect of different compatibilizers on injection-molded green fiber-reinforced polymers based on poly(lactic acid)-maleinized linseed oil system and sheep wool. Polymers 2019, 11, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.Z.; Deiab, I.; Darras, B.M. Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), green alternatives to petroleum-based plastics: A review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 17151–17196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spasojevic, P.; Seslija, S.; Markovic, M.; Pantic, O.; Antic, K.; Spasojevic, M. Optimization of reactive diluent for bio-based unsaturated polyester resin: A rheological and thermomechanical study. Polymers 2021, 13, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisar, J.; Pummerova, M.; Drohsler, P.; Masar, M.; Sedlarik, V. Changes in the thermal and structural properties of polylactide and its composites during a long-term degradation process. Polymers 2025, 17, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaavessina, M.; Distantina, S.; Chafidz, A.; Utama, A.; Anggraeni, V.M.P. Blends of low molecular weight poly(lactic acid) (PLA) with gondorukem (gum rosin). AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1931, 030006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, V.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Perspective on poly(lactic acid) (PLA)-based sustainable materials for durable applications: Focus on toughness and heat resistance. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2899–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physical Property | Commercial Name | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminy® LX-175 | Luminy® L130 | Ingeo™ 2003D | Ingeo™ 6201D | |

| Molecular weight (kg mol−1) | 245 b | 170 b | 120 b | 59 b |

| Density (g cm−3) | 1.24 a,b | 1.24 b | 1.24 a,b | 1.24 b |

| Melting temperature Tm DSC (°C) | 155 a | 175 a | 145–160 a | 155–170 a |

| Glass transition temperature Tg DSC (°C) | 60 a | 60 a | 55–60 a | 55–60 a |

| MFR (210 °C/2.16 kg) (g 10 min−1) | 8 b | 23 a | 6 a,b | 15–30 b |

| MFR (190 °C/2.16 kg) (g 10 min−1) | 3 b | 10 b | Not detailed | Not detailed |

| Stereochemical purity (% L-isomer) | 96 a | min. 99 a | 95.7 b | 98.6 b |

| Sample Label | PLA Grade | UP Content (phr) |

|---|---|---|

| PLA (LX-175)-UP (3 phr) | LX-175 | 3 |

| PLA (L130)-UP (3 phr) | L130 | 3 |

| PLA (2003D)-UP (3 phr) | 2003D | 3 |

| PLA (6201D)-UP (3 phr) | 6201D | 3 |

| TGA | DSC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | T5% (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Char Residue (%) (at 600 °C) | Tg (°C) | Tcc (°C) | ΔHcc (Jg−1) | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (Jg−1) | Xc (%) |

| PLA (LX-175) | 309.8 | 343.5 | 1.8 | 61.6 | 131.5 | 20.6 | 159.3 | 22.1 | 1.6 |

| PLA (LX-175)-UP (3 phr) | 304.7 | 341.7 | 1.6 | 61.4 | 132.7 | 8.7 | 158.8 | 8.7 | <0.5 * |

| PLA (L130) | 313.6 | 345.9 | 1.8 | 61.9 | 106.2 | 39.6 | 175.4 | 48.9 | 10.0 |

| PLA (L130)-UP (3 phr) | 310.4 | 345.8 | 1.3 | 62.1 | 109.3 | 34.4 | 174.8 | 46.4 | 12.9 |

| PLA (2003D) | 312.8 | 347.1 | 1.6 | 61.3 | 125.3 | 13.2 | 151.4 | 13.6 | 0.4 |

| PLA (2003D)-UP (3 phr) | 307.7 | 341.3 | 1.0 | 61.3 | - | - | 152.1 | 0.2 | <0.5 * |

| PLA (6201D) | 305.8 | 343.4 | 1.2 | 62.9 | 125.4 | 27.9 | 172.0 | 41.4 | 14.5 |

| PLA (6201D)-UP (3 phr) | 302.3 | 343.1 | 0.8 | 62.0 | 111.0 | 41.2 | 170.6 | 44.0 | 3.1 |

| Unmodified PLA | Toughness (kJ/m3) | Modified PLA | Toughness (kJ/m3) | Toughness Increment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA (LX-175) | 2585.2 ± 30.4 | PLA (LX-175)-UP(3 phr) | 3313.9 ± 32.8 | 28.2 |

| PLA (L130) | 2411.5 ± 37.8 | PLA (L130)-UP(3 phr) | 3415.0 ± 41.5 | 41.6 |

| PLA (2003D) | 2372.9 ± 35.6 | PLA (2003D)-UP(3 phr) | 3939.5 ± 52.5 | 66.0 |

| PLA (6201D) | 2654.2 ± 46.7 | PLA (6201D)-UP(3 phr) | 3537.9 ± 37.2 | 33.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosa-Ramírez, H.d.l.; Aldas, M.; Pavon, C.; Dominici, F.; Rallini, M.; Puglia, D.; Torre, L.; López-Martínez, J.; Samper, M.D. Design and Characterization of Sustainable PLA-Based Systems Modified with a Rosin-Derived Resin: Structure–Property Relationships and Functional Performance. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120801

Rosa-Ramírez Hdl, Aldas M, Pavon C, Dominici F, Rallini M, Puglia D, Torre L, López-Martínez J, Samper MD. Design and Characterization of Sustainable PLA-Based Systems Modified with a Rosin-Derived Resin: Structure–Property Relationships and Functional Performance. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(12):801. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120801

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosa-Ramírez, Harrison de la, Miguel Aldas, Cristina Pavon, Franco Dominici, Marco Rallini, Debora Puglia, Luigi Torre, Juan López-Martínez, and María Dolores Samper. 2025. "Design and Characterization of Sustainable PLA-Based Systems Modified with a Rosin-Derived Resin: Structure–Property Relationships and Functional Performance" Biomimetics 10, no. 12: 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120801

APA StyleRosa-Ramírez, H. d. l., Aldas, M., Pavon, C., Dominici, F., Rallini, M., Puglia, D., Torre, L., López-Martínez, J., & Samper, M. D. (2025). Design and Characterization of Sustainable PLA-Based Systems Modified with a Rosin-Derived Resin: Structure–Property Relationships and Functional Performance. Biomimetics, 10(12), 801. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10120801