MEIAO: A Multi-Strategy Enhanced Information Acquisition Optimizer for Global Optimization and UAV Path Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The integration of Levy Flight-based information collection, adaptive differential evolution, and globally guided boundary handling into the original IAO results in the proposed MEIAO, which comprehensively enhances algorithm performance in high-dimensional, multimodal, and complex-constrained scenarios.

- (2)

- Extensive experiments on the CEC2017 and CEC2022 benchmark suites compare MEIAO with eight mainstream algorithms. Evaluation metrics including mean, standard deviation, Friedman mean rank, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests demonstrate MEIAO’s superior performance in local exploitation of unimodal functions, global exploration of multimodal functions, and complex adaptation of composite functions.

- (3)

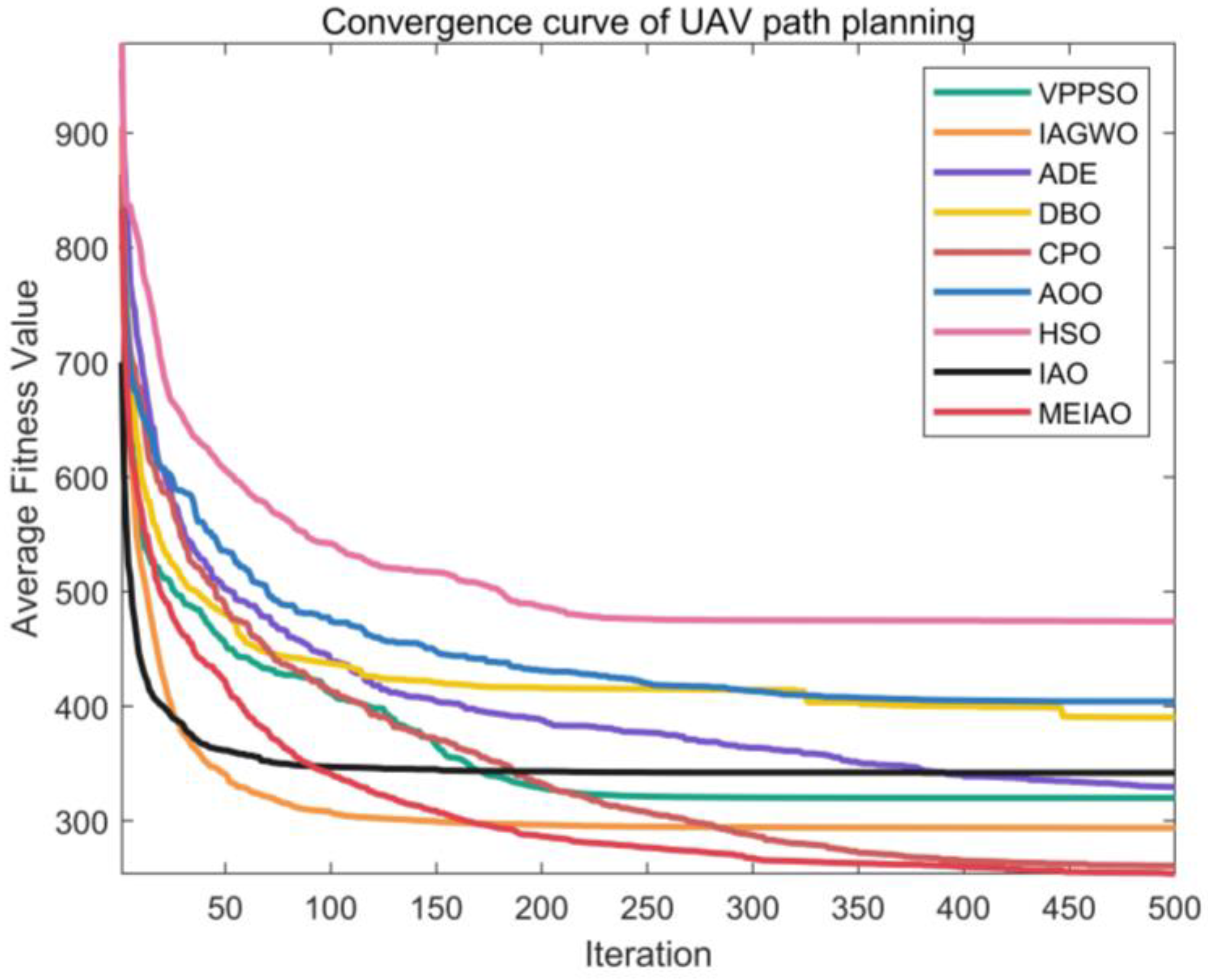

- MEIAO is applied to UAV path planning in 3D mountainous environments, with a comprehensive cost optimization model considering path length, altitude standard deviation, and turning smoothness. Through quantitative analysis of path costs (best/worst/average), 3D path visualization, and convergence curves, MEIAO is shown to generate shorter, smoother, and collision-free feasible paths. It also exhibits strong robustness across multiple trials, providing an efficient and reliable path optimization solution for practical UAV operations.

2. Information Acquisition Optimizer and the Proposed Methodology

2.1. Information Acquisition Optimizer (IAO)

2.1.1. Information Collection

2.1.2. Information Filtering and Evaluation

2.1.3. Information Analysis and Organization

2.2. Proposed Multi-Strategy Enhanced Information Acquisition Optimizer (MEIAO)

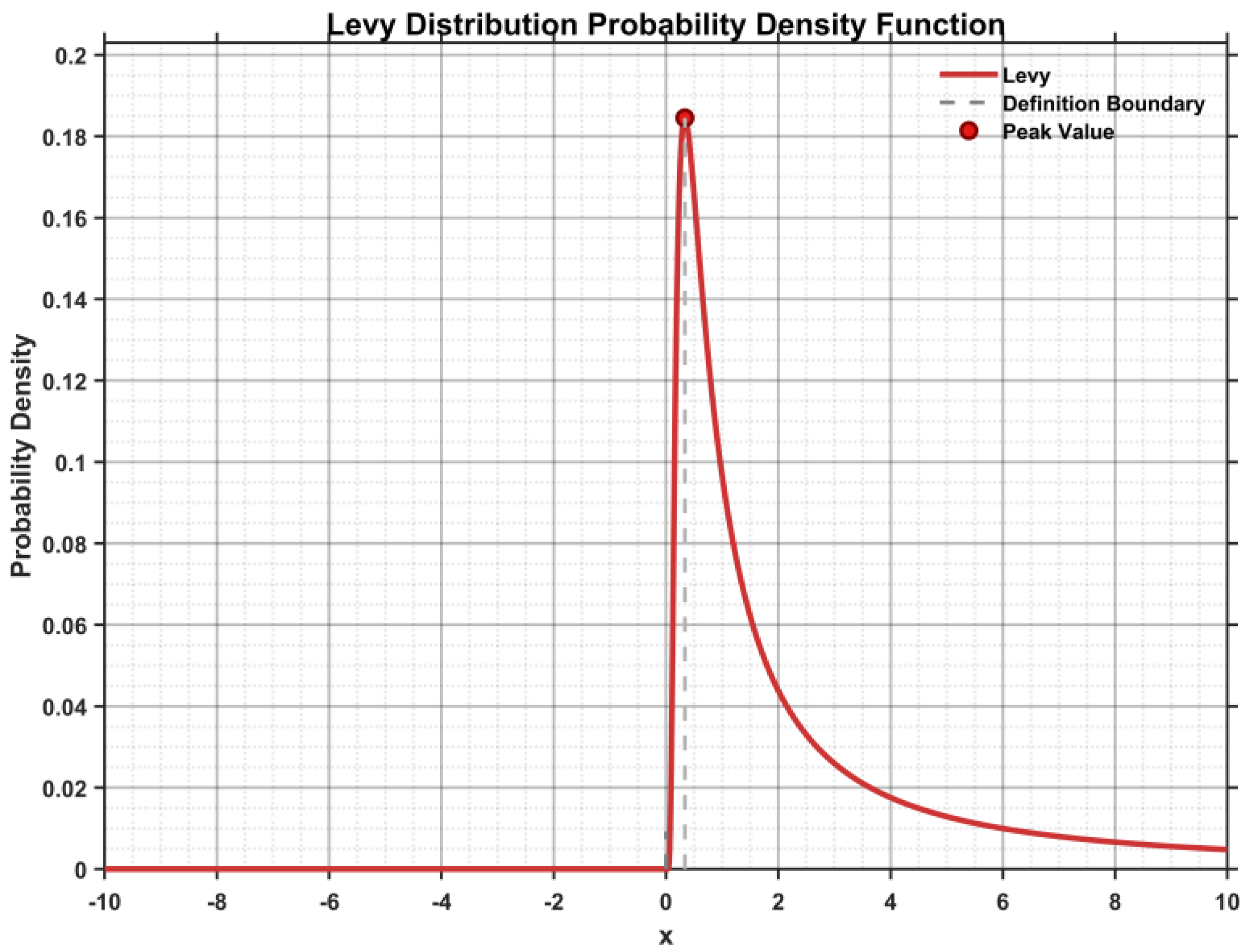

2.2.1. Levy Flight-Based Information Collection Strategy

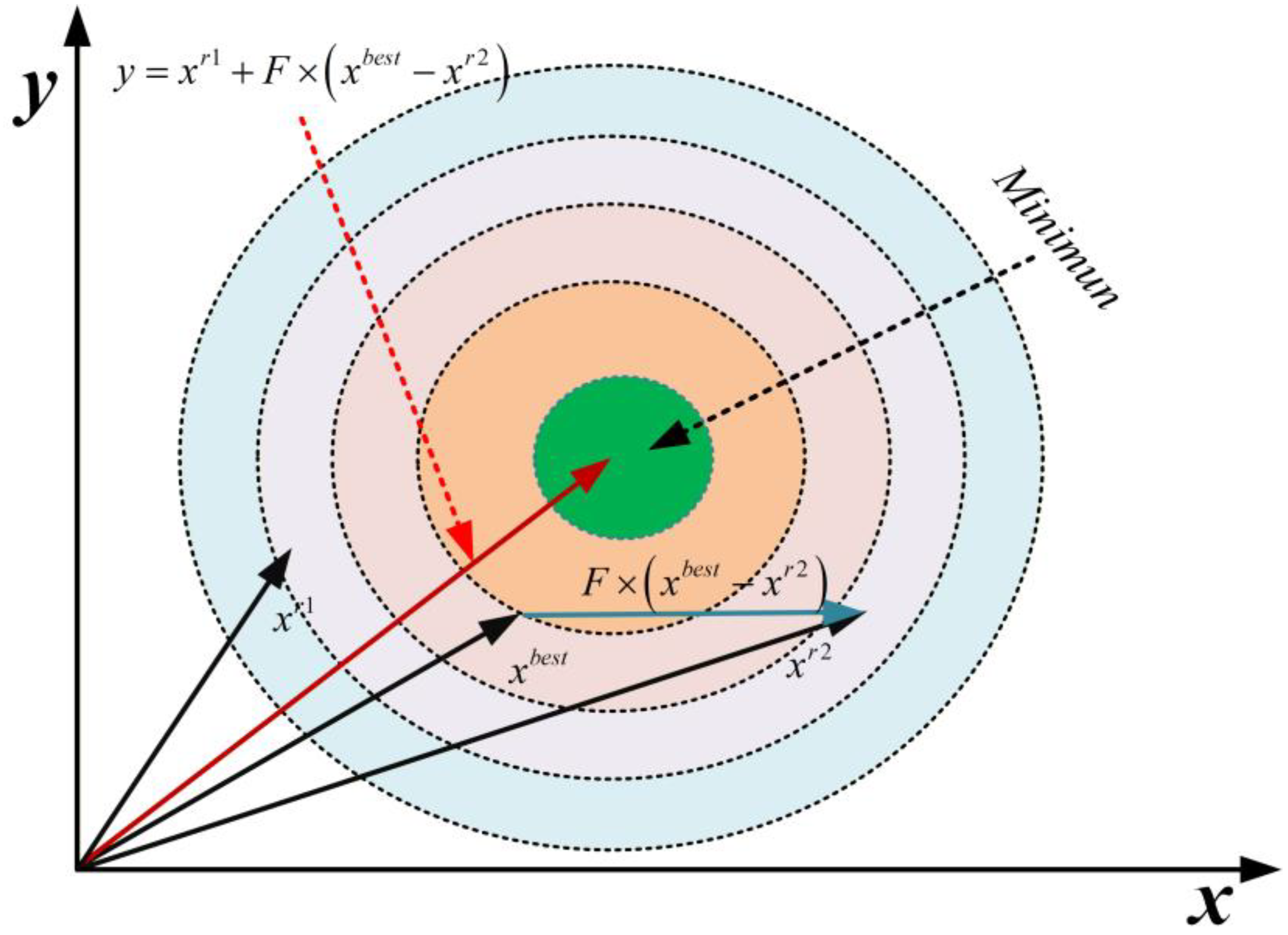

2.2.2. Adaptive Differential Evolution Operator

- Design of the adaptive mutation factor

- 2.

- Crossover operation and greedy selection

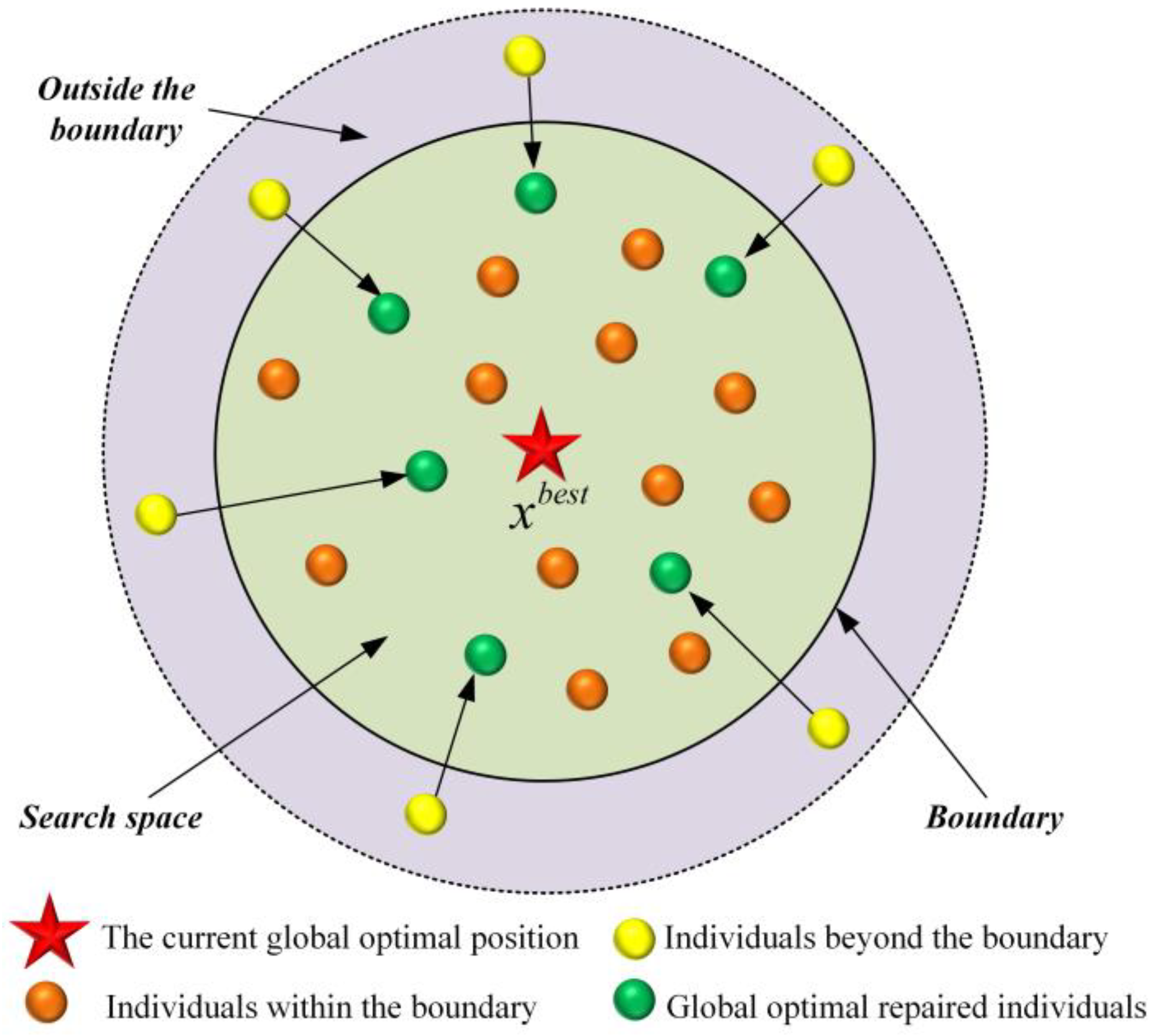

2.2.3. Global Optimal Guided Boundary Processing Strategy

| Algorithm 1. Pseudo-Code of MEIAO |

| 1: Initialize Problem Setting (population(N), dim, ub, lb), Max iterations. 2: Initialize the solution’s positions (). 3: while do 4: Calculate the energy factor using Equation (8). 5: Generate a random number between . 6: Generate randomly two integers and between . 7: Generate a candidate population by Equations (8)–(10). 8: for do 9: Calculate the fitness by Equations (2)–(5). 10: Boundary processing by Equation (15). 11: end for 12: for do 13: Calculate the fitness by Equations (6) and (7). 14: Boundary processing by Equation (15). 15: end for 16: Adaptive differential evolution operator by Equations (11)–(14). 17: Boundary processing by Equation (15). 18: end for 19: Update the position of solution and its fitness value. 20: Find the best solution position and fitness value so far. 21: end while 22: Return the best solution. |

2.3. Evaluation of MEIAO’s Computational Efficiency

3. Numerical Experiments

3.1. Settings of Key Algorithm Parameters

3.2. Qualitative Analysis of MEIAO

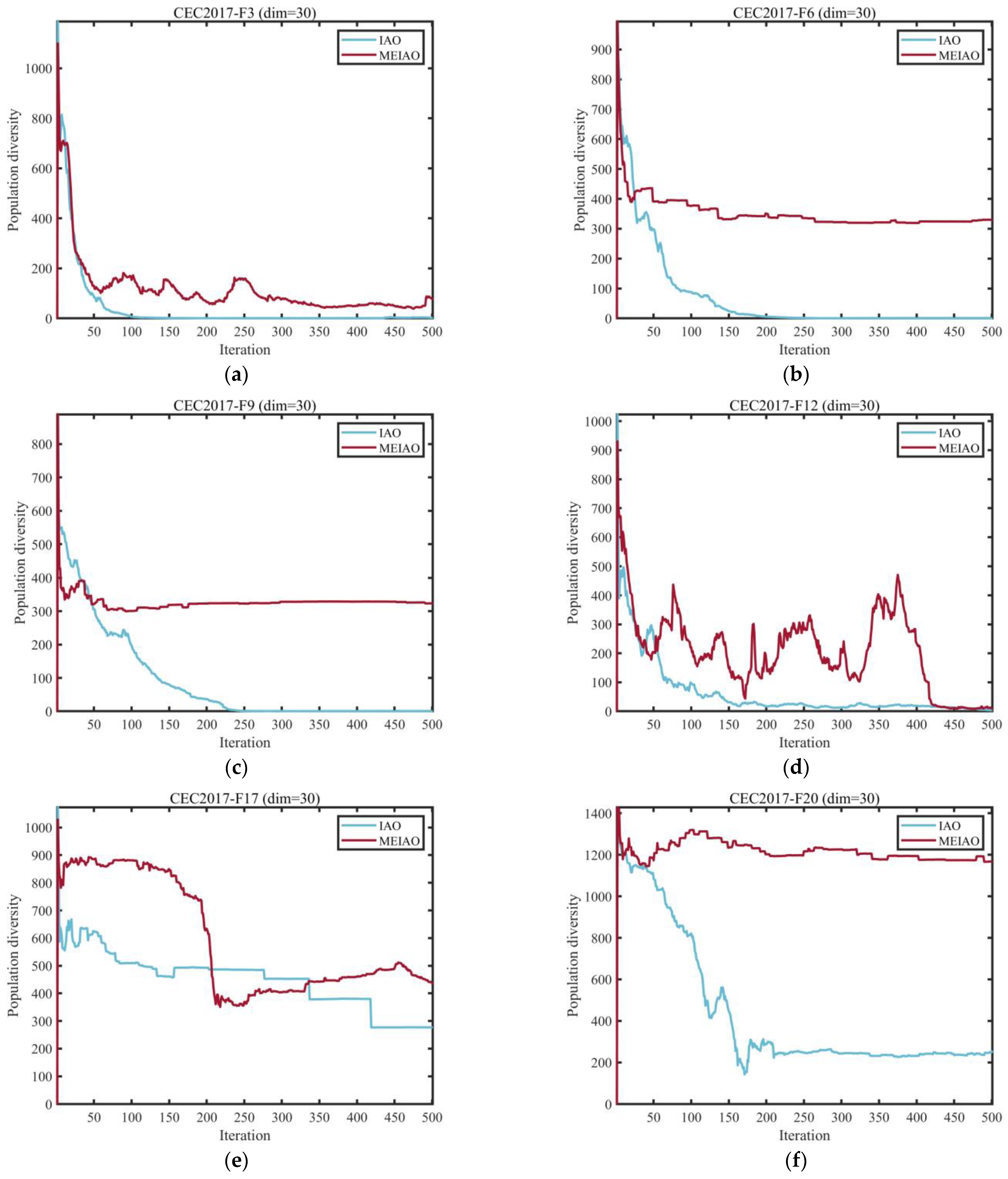

3.2.1. Analysis of the Population Diversity

3.2.2. Evaluation of Exploration and Exploitation Behavior

3.2.3. Assessment of the Effects of the Proposed Strategy

3.2.4. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

3.3. Experimental Results and Analysis of CEC2017 and CEC2022 Test Suite

3.4. Statistical Analysis

3.4.1. Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test

3.4.2. Friedman Mean Rank Test

4. Evaluate the Proposed MEIAO for UAV Path Planning

4.1. Three-Dimensional Mathematical Model

4.2. Simulation Experiment

5. Summary and Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gong, R.; Gong, H.; Hong, L.; Li, T.; Xiang, C. A novel marine predator algorithm for path planning of UAVs. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Huang, P.; Gao, H.; Qin, Q.; Guo, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. A Photosensitivity-Enhanced Plant Growth Algorithm for UAV Path Planning. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jia, C.; Zhao, J.; Xia, C.; Peng, W.; Huang, J.; Li, L. An Enhanced Artificial Lemming Algorithm and Its Application in UAV Path Planning. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, N.; Boudjit, S.; Dauphin, G.; Zeadally, S. An obstacle avoidance approach for UAV path planning. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2023, 129, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Chen, J. Adaptive path planning method for UAVs in complex environments. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 115, 103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Zou, A.; Cai, J.; He, H.; Tan, T. Path Planning for UAV Based on Improved PRM. Energies 2022, 15, 7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Y. Survey on computational-intelligence-based UAV path planning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2018, 158, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Saripalli, S. Sampling-Based Path Planning for UAV Collision Avoidance. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 18, 3179–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, M. An improved chaos sparrow search algorithm for UAV path planning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Su, Y.; Xie, A.; Kong, L. A newly bio-inspired path planning algorithm for autonomous obstacle avoidance of UAV. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, S.; Ding, Y.; Qin, X.; Xia, Q. UAV Path Planning Algorithm Based on Improved Harris Hawks Optimization. Sensors 2022, 22, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W. FC-RRT*: An Improved Path Planning Algorithm for UAV in 3D Complex Environment. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, R.; Li, S. A Novel Improved Dung Beetle Optimization Algorithm for Collaborative 3D Path Planning of UAVs. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yan, F.; Zhang, J.; Peng, C. Hybrid chaos game and grey wolf optimization algorithms for UAV path planning. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 142, 115979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Chen, C. DBO-AWOA: An Adaptive Whale Optimization Algorithm for Global Optimization and UAV 3D Path Planning. Sensors 2025, 25, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Research of UAV 3D path planning based on improved Dwarf mongoose algorithm with multiple strategies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhao, H.; Lyu, L.; Yang, F. Multi-strategy improved gazelle optimization algorithm for numerical optimization and UAV path planning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; Volume 1944, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt, C.D.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The Whale Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: A new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. J. Supercomput. 2022, 79, 7305–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; He, L. Secretary bird optimization algorithm: A new metaheuristic for solving global optimization problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, K.; Huang, H.; Ma, C.; Fan, Q.; Zhu, Y. Red-billed blue magpie optimizer: A novel metaheuristic algorithm for 2D/3D UAV path planning and engineering design problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Diabat, A.; Mirjalili, S.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Gandomi, A.H. The Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 376, 113609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Ren, C.; Niu, J.; Wang, P.; Shang, Y. Great Wall Construction Algorithm: A novel meta-heuristic algorithm for engineer problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 233, 120905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-L.; Gu, S.-W.; Liu, R.-J.; Chen, L.-Q.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, Z.-Q. Cuckoo catfish optimizer: A new meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Escape after love: Philoponella prominens optimizer and its application to 3D path planning. Clust. Comput. 2024, 28, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Khodadadi, N.; Trojovský, P.; Li, L.; Mansor, Z.; Abualigah, L.; Alharbi, A.H.; El-Kenawy, E.-S.M. Kirchhoff’s law algorithm (KLA): A novel physics-inspired non-parametric metaheuristic algorithm for optimization problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, G.; Mirjalili, S.; Khodadadi, N.; Hussien, A.G.; Liao, Y.; Zhao, W. Tianji’s horse racing optimization (THRO): A new metaheuristic inspired by ancient wisdom and its engineering optimization applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braik, M.; Al-Hiary, H.; Alzoubi, H.; Hammouri, A.; Azmi Al-Betar, M.; Awadallah, M.A. Tornado optimizer with Coriolis force: A novel bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for solving engineering problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1997, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharet, D.G.; Neto, A.A.; Campos, M.F.M. Feasible UAV Path Planning Using Genetic Algorithms and Bézier Curves. In Proceedings of the Advances in Artificial Intelligence—SBIA 2010, São Bernardo do Campo, Brazil, 23–28 October 2010; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, S.; Peng, Y.; He, C.; Du, Y. Efficient path planning for UAV formation via comprehensively improved particle swarm optimization. ISA Trans. 2020, 97, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, N.; Shang, J. Multi-UAV Path Planning Based on Fusion of Sparrow Search Algorithm and Improved Bioinspired Neural Network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 124670–124681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Gao, F.; Fang, X.; Lan, Z. Improved Bat Algorithm for UAV Path Planning in Three-Dimensional Space. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 20100–20116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhou, X.; Ran, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Deng, W. Adaptive cylinder vector particle swarm optimization with differential evolution for UAV path planning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 121, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Gai, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, M. A novel hybrid grey wolf optimizer algorithm for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) path planning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 194, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, N.; Wang, X.; Li, M. A hybrid algorithm based on grey wolf optimizer and differential evolution for UAV path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 215, 119327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hao, Z. Multi-Strategy Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm and Its Engineering Applications. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Q.; Wu, X.; Wan, L.; Huang, J. Secretary bird optimization algorithm based on quantum computing and multiple strategies improvement for KELM diabetes classification. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Y. Information acquisition optimizer: A new efficient algorithm for solving numerical and constrained engineering optimization problems. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 25736–25791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shami, T.M.; Mirjalili, S.; Al-Eryani, Y.; Daoudi, K.; Izadi, S.; Abualigah, L. Velocity pausing particle swarm optimization: A novel variant for global optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 9193–9223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Xu, J.; Liang, W.; Qiu, Y.; Bao, S.; Tang, L. Improved multi-strategy adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization for practical engineering applications and high-dimensional problem solving. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, B.; Majidnezhad, V.; Mirjalili, S. ADE: Advanced differential evolution. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 15407–15438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, R.; Abouhawwash, M. Crested Porcupine Optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 284, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-B.; Hu, R.-B.; Geng, F.-D.; Xu, L.; Chu, S.-C.; Pan, J.-S.; Meng, Z.-Y.; Mirjalili, S. The Animated Oat Optimization Algorithm: A nature-inspired metaheuristic for engineering optimization and a case study on Wireless Sensor Networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 318, 113589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Rahimnejad, A.; Gadsden, S.A. Holistic swarm optimization: A novel metaphor-less algorithm guided by whole population information for addressing exploration-exploitation dilemma. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 445, 118208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Qin, F.; Zhou, K.-Q.; Yin, P.-F.; Mo, L.-P.; Mohd Zain, A.J.S. An improved grey wolf optimizer with multi-strategies coverage in wireless sensor networks. Symmetry 2024, 16, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Houssein, E.H.; Mostafa, R.R.; Hussien, A.G.; Helmy, F. An efficient adaptive-mutated Coati optimization algorithm for feature selection and global optimization. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 85, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-c.; Tian, W.-c.; Xu, D.-m.; Zang, H.-f. Arctic puffin optimization: A bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering design optimization. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 195, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.O.; Aghdasi, H.S.; Salehpour, P. Dhole optimization algorithm: A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Yang, F. MMPA: A modified marine predator algorithm for 3D UAV path planning in complex environments with multiple threats. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 257, 124955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Soleimanian Gharehchopogh, F.; Mirjalili, S. An improved whale optimization algorithm based on multi-population evolution for global optimization and engineering design problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 215, 119269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belge, E.; Altan, A.; Hacioglu, R. Metaheuristic Optimization-Based Path Planning and Tracking of Quadcopter for Payload Hold-Release Mission. Electronics 2022, 11, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Fu, Y. Augmented Harris hawks optimization and for engineering design problems and UAV path planning. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2025, 16, 6295–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.; Ren, J. Dynamic Mission Planning Algorithm for UAV Formation in Battlefield Environment. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 3750–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithms | Name of the Parameter | Value of the Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| VPPSO | 2, 2, 0.8, [1,0], 0.15, 0.15 | |

| IAGWO | [−20,20], [0,2], [0.3,0.9], 0.5 | |

| ADE | 4, 28, 0.2 | |

| DBO | ||

| CPO | ||

| AOO | ||

| HSO | 3 | |

| IAO | ||

| MEIAO |

| Function | Metric | VPPSO | IAGWO | ADE | DBO | CPO | AOO | HSO | IAO | MEIAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Ave | 5.6690 × 106 | 1.7196 × 106 | 4.7848 × 106 | 2.5261 × 108 | 7.8801 × 105 | 8.4743 × 104 | 9.1857 × 103 | 4.1305 × 1010 | 3.9158 × 103 |

| Std | 2.5932 × 107 | 7.7368 × 105 | 2.9861 × 106 | 1.5725 × 108 | 6.9025 × 105 | 4.4261 × 104 | 7.7074 × 103 | 7.9398 × 109 | 4.5756 × 103 | |

| F2 | Ave | 1.6098 × 1023 | 1.4519 × 1033 | 2.9671 × 1032 | 1.7732 × 1032 | 5.3667 × 1023 | 3.3146 × 1016 | 1.2694 × 1016 | 2.9482 × 1037 | 1.9892 × 1012 |

| Std | 4.8590 × 1023 | 7.6387 × 1033 | 1.0651 × 1033 | 9.4488 × 1032 | 2.9378 × 1024 | 7.4215 × 1016 | 3.1881 × 1016 | 1.6066 × 1038 | 7.7583 × 1012 | |

| F3 | Ave | 4.4098 × 104 | 5.5238 × 104 | 1.5964 × 105 | 9.5621 × 104 | 6.1922 × 104 | 2.8241 × 104 | 5.0767 × 104 | 5.6804 × 104 | 8.3114 × 103 |

| Std | 1.0947 × 104 | 1.7144 × 104 | 3.7210 × 104 | 3.5696 × 104 | 1.1275 × 104 | 1.1583 × 104 | 1.1256 × 104 | 1.2667 × 104 | 3.3681 × 103 | |

| F4 | Ave | 5.2585 × 102 | 6.1821 × 102 | 5.1202 × 102 | 6.4624 × 102 | 5.1317 × 102 | 5.0597 × 102 | 7.1004 × 102 | 8.1367 × 103 | 4.8202 × 102 |

| Std | 2.9692 × 101 | 2.0992 × 102 | 2.1201 × 101 | 1.1306 × 102 | 1.7954 × 101 | 2.3804 × 101 | 1.2088 × 102 | 3.7042 × 103 | 3.8188 × 101 | |

| F5 | Ave | 6.4802 × 102 | 6.5832 × 102 | 6.9209 × 102 | 7.3702 × 102 | 6.9559 × 102 | 6.2225 × 102 | 6.9554 × 102 | 7.8512 × 102 | 5.9882 × 102 |

| Std | 3.3030 × 101 | 3.0228 × 101 | 1.4269 × 101 | 5.4960 × 101 | 1.3094 × 101 | 3.4383 × 101 | 3.2265 × 101 | 3.4714 × 101 | 2.9908 × 101 | |

| F6 | Ave | 6.3982 × 102 | 6.2087 × 102 | 6.0086 × 102 | 6.5289 × 102 | 6.0195 × 102 | 6.2937 × 102 | 6.4985 × 102 | 6.6317 × 102 | 6.0005 × 102 |

| Std | 8.6758 × 100 | 8.9957 × 100 | 2.8585 × 10-1 | 1.3621 × 101 | 6.4276 × 10-1 | 1.2878 × 101 | 4.3994 × 100 | 9.6443 × 100 | 1.2340 × 10-1 | |

| F7 | Ave | 9.5491 × 102 | 9.2931 × 102 | 9.5104 × 102 | 1.0321 × 103 | 9.3631 × 102 | 8.6880 × 102 | 1.0261 × 103 | 1.2451 × 103 | 8.5076 × 102 |

| Std | 7.2265 × 101 | 4.2149 × 101 | 1.6110 × 101 | 7.3775 × 101 | 1.8655 × 101 | 3.1376 × 101 | 6.7642 × 101 | 7.1681 × 101 | 4.0520 × 101 | |

| F8 | Ave | 9.2517 × 102 | 9.2110 × 102 | 9.9923 × 102 | 1.0252 × 103 | 9.8488 × 102 | 9.1146 × 102 | 1.0499 × 103 | 1.0379 × 103 | 8.9811 × 102 |

| Std | 2.7880 × 101 | 2.5167 × 101 | 1.4565 × 101 | 5.4044 × 101 | 1.5220 × 101 | 2.6424 × 101 | 2.6958 × 101 | 1.8622 × 101 | 2.4641 × 101 | |

| F9 | Ave | 3.8477 × 103 | 4.4491 × 103 | 2.2953 × 103 | 7.4125 × 103 | 1.3123 × 103 | 3.5631 × 103 | 2.6024 × 103 | 6.7736 × 103 | 1.1765 × 103 |

| Std | 1.2047 × 103 | 1.0776 × 103 | 7.7471 × 102 | 2.7722 × 103 | 2.3559 × 102 | 1.3125 × 103 | 7.1535 × 102 | 9.0925 × 102 | 5.0249 × 102 | |

| F10 | Ave | 4.8963 × 103 | 4.4177 × 103 | 7.5573 × 103 | 6.6404 × 103 | 7.6832 × 103 | 4.8879 × 103 | 4.1716 × 103 | 6.5395 × 103 | 5.0975 × 103 |

| Std | 6.2399 × 102 | 5.1742 × 102 | 3.0922 × 102 | 1.1699 × 103 | 2.4277 × 102 | 6.6403 × 102 | 5.9473 × 102 | 4.8619 × 102 | 1.0348 × 103 | |

| F11 | Ave | 1.4231 × 103 | 1.9963 × 103 | 2.1519 × 103 | 1.8908 × 103 | 1.2701 × 103 | 1.2820 × 103 | 1.7550 × 103 | 2.7124 × 103 | 1.1985 × 103 |

| Std | 1.2364 × 102 | 1.0616 × 103 | 7.7332 × 102 | 5.6341 × 102 | 2.3177 × 101 | 5.6131 × 101 | 1.6297 × 102 | 1.0344 × 103 | 5.0022 × 101 | |

| F12 | Ave | 2.3167 × 107 | 2.9292 × 107 | 2.5697 × 107 | 5.4373 × 107 | 9.9186 × 105 | 1.2236 × 107 | 4.8375 × 105 | 2.9285 × 109 | 1.0331 × 105 |

| Std | 1.6452 × 107 | 3.9613 × 107 | 1.4775 × 107 | 8.6360 × 107 | 4.4788 × 105 | 1.0567 × 107 | 7.7607 × 105 | 2.0293 × 109 | 5.8236 × 104 | |

| F13 | Ave | 9.6858 × 104 | 9.0303 × 104 | 2.6443 × 106 | 8.7064 × 106 | 1.8638 × 104 | 1.1176 × 105 | 2.7696 × 104 | 1.3956 × 105 | 1.5235 × 104 |

| Std | 4.1162 × 104 | 4.1336 × 105 | 4.8583 × 106 | 1.8910 × 107 | 9.4613 × 103 | 6.1402 × 104 | 2.5883 × 104 | 1.3814 × 105 | 1.2447 × 104 | |

| F14 | Ave | 9.8899 × 104 | 6.8194 × 105 | 5.2854 × 105 | 2.6880 × 105 | 2.1858 × 103 | 6.5224 × 104 | 1.1323 × 104 | 1.6171 × 103 | 2.4378 × 103 |

| Std | 8.8113 × 104 | 5.0770 × 105 | 4.7443 × 105 | 4.0834 × 105 | 8.0051 × 102 | 5.1982 × 104 | 1.4594 × 104 | 6.9851 × 101 | 2.0571 × 103 | |

| F15 | Ave | 5.0031 × 104 | 6.6572 × 103 | 3.9512 × 105 | 1.0727 × 105 | 5.1724 × 103 | 5.3607 × 104 | 9.6234 × 103 | 9.4019 × 103 | 3.4686 × 103 |

| Std | 5.2911 × 104 | 5.1594 × 103 | 3.2991 × 105 | 1.0802 × 105 | 4.2356 × 103 | 4.3377 × 104 | 5.3313 × 103 | 5.8916 × 103 | 2.1578 × 103 | |

| F16 | Ave | 2.8199 × 103 | 3.0840 × 103 | 3.0126 × 103 | 3.3568 × 103 | 3.1547 × 103 | 2.8082 × 103 | 2.8221 × 103 | 3.0147 × 103 | 2.2456 × 103 |

| Std | 2.8000 × 102 | 3.6801 × 102 | 1.9417 × 102 | 4.0722 × 102 | 2.0782 × 102 | 3.3971 × 102 | 3.4491 × 102 | 3.9271 × 102 | 1.9430 × 102 | |

| F17 | Ave | 2.1317 × 102 | 2.3921 × 103 | 2.2180 × 103 | 2.6455 × 103 | 2.0858 × 103 | 2.1587 × 103 | 2.6166 × 103 | 2.1558 × 103 | 1.8550 × 103 |

| Std | 2.1093 × 102 | 2.3588 × 102 | 1.3183 × 102 | 2.6845 × 102 | 1.1495 × 102 | 2.0909 × 102 | 2.8349 × 102 | 1.2667 × 102 | 9.0259 × 101 | |

| F18 | Ave | 8.0407 × 105 | 1.4113 × 106 | 3.5970 × 106 | 3.9830 × 106 | 1.4249 × 105 | 1.3471 × 106 | 1.8414 × 105 | 3.5612 × 104 | 5.7037 × 104 |

| Std | 7.4493 × 105 | 2.3882 × 106 | 1.9999 × 106 | 4.4045 × 106 | 1.3729 × 105 | 1.2929 × 106 | 1.5553 × 105 | 2.9136 × 104 | 3.5610 × 104 | |

| F19 | Ave | 2.1676 × 106 | 9.0207 × 103 | 5.0354 × 105 | 6.6217 × 106 | 5.8460 × 103 | 5.9576 × 105 | 1.2680 × 104 | 1.7063 × 105 | 4.2762 × 103 |

| Std | 1.4330 × 106 | 6.9685 × 103 | 6.7714 × 105 | 2.0342 × 107 | 3.2263 × 103 | 9.0051 × 105 | 1.0265 × 104 | 3.0535 × 105 | 2.7734 × 103 | |

| F20 | Ave | 2.5403 × 103 | 2.6639 × 103 | 2.5282 × 103 | 2.6826 × 103 | 2.4734 × 103 | 2.4766 × 103 | 2.6210 × 103 | 2.4449 × 103 | 2.2019 × 103 |

| Std | 1.9672 × 102 | 2.8078 × 102 | 9.4061 × 101 | 2.3210 × 102 | 1.2799 × 102 | 1.8194 × 102 | 2.5989 × 102 | 9.6247 × 101 | 9.2881 × 101 | |

| F21 | Ave | 2.4236 × 103 | 2.4502 × 103 | 2.4922 × 103 | 2.5749 × 103 | 2.4835 × 103 | 2.4052 × 103 | 2.5754 × 103 | 2.5781 × 103 | 2.3733 × 103 |

| Std | 3.2354 × 101 | 3.0929 × 101 | 1.3765 × 101 | 3.8033 × 101 | 1.7068 × 101 | 1.8580 × 101 | 1.9217 × 101 | 4.7140 × 101 | 2.0044 × 101 | |

| F22 | Ave | 2.8635 × 103 | 3.6435 × 103 | 8.2993 × 103 | 5.1692 × 103 | 2.3087 × 103 | 4.3348 × 103 | 4.6175 × 103 | 6.4418 × 103 | 2.3007 × 103 |

| Std | 1.3622 × 103 | 1.9491 × 103 | 1.3300 × 103 | 2.3880 × 103 | 2.6450 × 100 | 2.1234 × 103 | 1.7695 × 103 | 1.1595 × 103 | 1.4514 × 100 | |

| F23 | Ave | 2.8216 × 103 | 3.0915 × 103 | 2.8440 × 103 | 3.0256 × 103 | 2.8462 × 103 | 2.7910 × 103 | 2.9108 × 103 | 3.0503 × 103 | 2.7211 × 103 |

| Std | 5.8145 × 101 | 1.3892 × 102 | 1.8851 × 101 | 9.2318 × 101 | 1.8488 × 101 | 4.6115 × 101 | 1.4101 × 101 | 6.5105 × 101 | 2.6615 × 101 | |

| F24 | Ave | 2.9542 × 103 | 3.3170 × 103 | 3.0399 × 103 | 3.1835 × 103 | 3.0147 × 103 | 2.9661 × 103 | 3.0428 × 103 | 3.2188 × 103 | 2.8836 × 103 |

| Std | 4.6096 × 101 | 1.3003 × 102 | 1.8516 × 101 | 8.6162 × 101 | 1.8863 × 101 | 5.5403 × 101 | 1.2211 × 101 | 9.2672 × 101 | 1.5594 × 101 | |

| F25 | Ave | 2.9464 × 103 | 2.9479 × 103 | 2.9017 × 103 | 2.9680 × 103 | 2.9174 × 103 | 2.9106 × 103 | 3.1941 × 103 | 3.9002 × 103 | 2.8993 × 103 |

| Std | 2.3105 × 101 | 3.4193 × 101 | 6.8458 × 100 | 4.7377 × 101 | 1.7744 × 101 | 1.7010 × 101 | 8.8364 × 101 | 3.5360 × 102 | 1.7045 × 101 | |

| F26 | Ave | 4.6539 × 103 | 4.9468 × 103 | 5.5982 × 103 | 6.9814 × 103 | 4.4188 × 103 | 4.4033 × 103 | 5.3116 × 103 | 9.0990 × 103 | 3.3874 × 103 |

| Std | 1.3304 × 103 | 1.8361 × 103 | 1.4890 × 102 | 1.1188 × 103 | 1.4182 × 103 | 1.0682 × 103 | 2.7459 × 102 | 9.1218 × 102 | 7.7003 × 102 | |

| F27 | Ave | 3.2960 × 103 | 3.2311 × 103 | 3.2293 × 103 | 3.3437 × 103 | 3.2743 × 103 | 3.2564 × 103 | 3.3319 × 103 | 3.3688 × 103 | 3.2231 × 103 |

| Std | 4.5942 × 101 | 9.4039 × 101 | 7.4285 × 100 | 8.4743 × 101 | 1.1966 × 101 | 2.1780 × 101 | 5.3624 × 101 | 7.6658 × 101 | 1.3910 × 101 | |

| F28 | Ave | 3.3074 × 103 | 3.3806 × 103 | 3.3029 × 103 | 3.4689 × 103 | 3.2771 × 103 | 3.2434 × 103 | 3.6197 × 103 | 5.5229 × 103 | 3.2108 × 103 |

| Std | 2.6216 × 101 | 1.1706 × 102 | 1.8218 × 101 | 2.0189 × 102 | 2.8145 × 101 | 2.3446 × 101 | 1.3293 × 102 | 6.8478 × 102 | 1.5174 × 101 | |

| F29 | Ave | 4.3235 × 103 | 4.0141 × 103 | 4.2032 × 103 | 4.3755 × 103 | 4.0285 × 103 | 4.0544 × 103 | 4.4109 × 103 | 4.6288 × 103 | 3.5306 × 103 |

| Std | 2.2984 × 102 | 2.6755 × 102 | 1.3381 × 102 | 4.1062 × 102 | 1.2941 × 102 | 2.2522 × 102 | 2.8289 × 102 | 3.5041 × 102 | 1.4579 × 102 | |

| F30 | Ave | 7.7918 × 106 | 8.9931 × 105 | 4.9473 × 105 | 2.3378 × 106 | 1.3009 × 105 | 3.8818 × 106 | 1.0325 × 105 | 2.9842 × 106 | 8.5852 × 103 |

| Std | 4.8852 × 106 | 4.7353 × 106 | 4.7521 × 105 | 4.8571 × 106 | 7.1280 × 104 | 2.5847 × 106 | 2.2967 × 105 | 3.2378 × 106 | 2.5251 × 103 |

| Function | Metric | VPPSO | IAGWO | ADE | DBO | CPO | AOO | HSO | IAO | MEIAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Ave | 8.6519 × 108 | 1.6967 × 107 | 3.4660 × 108 | 7.5407 × 109 | 1.9149 × 108 | 1.6058 × 106 | 1.1395 × 105 | 9.1339 × 1010 | 3.0734 × 103 |

| Std | 8.6138 × 108 | 4.7766 × 106 | 1.9634 × 108 | 1.3188 × 1010 | 1.0618 × 108 | 7.1646 × 105 | 8.7181 × 104 | 1.1713 × 1010 | 4.2047 × 103 | |

| F2 | Ave | 8.2829 × 1052 | 5.9461 × 1059 | 1.8067 × 1065 | 1.2539 × 1071 | 5.6909 × 1045 | 5.1593 × 1043 | 1.8908 × 1047 | 2.4757 × 1073 | 3.7443 × 1030 |

| Std | 3.3455 × 1053 | 1.7432 × 1060 | 7.1925 × 1065 | 6.8679 × 1071 | 1.7901 × 1046 | 2.8048 × 1044 | 8.2975 × 1047 | 1.3516 × 1074 | 1.9272 × 1031 | |

| F3 | Ave | 1.5443 × 105 | 1.8438 × 105 | 3.3024 × 105 | 2.4440 × 105 | 1.8671 × 105 | 1.3498 × 105 | 1.4124 × 105 | 1.3800 × 105 | 6.2225 × 104 |

| Std | 2.2522 × 104 | 4.1368 × 104 | 5.2828 × 104 | 5.3706 × 104 | 2.1483 × 104 | 2.7651 × 104 | 2.2548 × 104 | 1.9540 × 104 | 1.0831 × 104 | |

| F4 | Ave | 8.2473 × 102 | 7.0316 × 102 | 7.6686 × 102 | 1.3339 × 103 | 7.0386 × 102 | 6.3427 × 102 | 1.2444 × 103 | 2.4675 × 104 | 5.4567 × 102 |

| Std | 1.1894 × 102 | 9.8886 × 101 | 4.6648 × 101 | 4.8383 × 102 | 6.8080 × 101 | 5.3096 × 101 | 2.0276 × 102 | 4.8012 × 103 | 5.9264 × 101 | |

| F5 | Ave | 7.7832 × 102 | 7.7192 × 102 | 9.3231 × 102 | 9.7314 × 102 | 9.3263 × 102 | 7.6830 × 102 | 9.2216 × 102 | 1.0513 × 103 | 7.5704 × 102 |

| Std | 6.1473 × 101 | 3.0960 × 101 | 2.0089 × 101 | 1.0694 × 102 | 2.5165 × 101 | 4.8688 × 101 | 3.7878 × 101 | 3.3841 × 101 | 4.7710 × 101 | |

| F6 | Ave | 6.5344 × 102 | 6.3729 × 102 | 6.0620 × 102 | 6.6595 × 102 | 6.1072 × 102 | 6.5062 × 102 | 6.6846 × 102 | 6.8388 × 102 | 6.0140 × 102 |

| Std | 7.7034 × 100 | 7.5913 × 100 | 1.5077 × 100 | 9.3590 × 100 | 2.9076 × 100 | 1.0849 × 101 | 3.5738 × 100 | 5.6532 × 100 | 7.3146 × 10-1 | |

| F7 | Ave | 1.2520 × 103 | 1.1908 × 103 | 1.2590 × 103 | 1.4422 × 103 | 1.2505 × 103 | 1.0828 × 103 | 1.6340 × 103 | 1.8545 × 103 | 1.0906 × 103 |

| Std | 1.4127 × 101 | 7.1514 × 101 | 2.2955 × 101 | 1.4652 × 102 | 4.1872 × 101 | 9.4746 × 101 | 1.8819 × 102 | 1.0459 × 102 | 1.0441 × 102 | |

| F8 | Ave | 1.0802 × 103 | 1.0818 × 103 | 1.2327 × 103 | 1.3194 × 103 | 1.2184 × 103 | 1.0689 × 103 | 1.2888 × 103 | 1.3764 × 103 | 1.0685 × 103 |

| Std | 4.0636 × 101 | 3.6263 × 101 | 2.2151 × 101 | 1.0216 × 102 | 3.5062 × 101 | 6.6929 × 101 | 4.3488 × 101 | 3.4139 × 101 | 5.7494 × 101 | |

| F9 | Ave | 1.0020 × 104 | 1.5602 × 104 | 8.2739 × 103 | 2.7061 × 104 | 8.6308 × 103 | 1.2361 × 104 | 9.2946 × 103 | 2.5951 × 104 | 6.3306 × 103 |

| Std | 2.1513 × 103 | 3.1155 × 103 | 2.2699 × 103 | 7.1653 × 103 | 2.3180 × 103 | 4.1118 × 103 | 2.4588 × 103 | 2.5850 × 103 | 6.0180 × 103 | |

| F10 | Ave | 8.5719 × 103 | 7.0527 × 103 | 1.3867 × 104 | 1.1596 × 104 | 1.3639 × 104 | 7.9258 × 103 | 8.1840 × 103 | 1.2242 × 104 | 9.6841 × 103 |

| Std | 1.2876 × 103 | 1.2947 × 103 | 4.2281 × 102 | 2.2463 × 103 | 4.5364 × 102 | 9.5251 × 102 | 9.4520 × 102 | 4.8826 × 102 | 1.7152 × 103 | |

| F11 | Ave | 2.5830 × 103 | 4.8786 × 103 | 7.8303 × 103 | 4.3022 × 103 | 1.8897 × 103 | 1.5579 × 103 | 2.8510 × 103 | 1.5118 × 104 | 1.2659 × 103 |

| Std | 5.3000 × 102 | 3.0071 × 103 | 2.9027 × 103 | 1.6812 × 103 | 2.9842 × 102 | 8.8634 × 101 | 8.0991 × 102 | 3.8780 × 102 | 3.6211 × 103 | |

| F12 | Ave | 1.9132 × 108 | 1.2752 × 108 | 3.9502 × 108 | 7.4820 × 108 | 2.1047 × 107 | 8.5109 × 107 | 4.9589 × 106 | 4.1808 × 1010 | 2.8964 × 106 |

| Std | 1.2186 × 108 | 4.4245 × 108 | 1.6550 × 108 | 5.2333 × 108 | 9.3981 × 106 | 5.2053 × 107 | 5.5135 × 106 | 1.6144 × 1010 | 1.7058 × 106 | |

| F13 | Ave | 1.0844 × 105 | 5.7383 × 104 | 6.3902 × 106 | 1.5218 × 108 | 1.8196 × 104 | 1.3917 × 105 | 3.0575 × 104 | 8.9552 × 109 | 5.5717 × 103 |

| Std | 5.5370 × 104 | 2.0077 × 105 | 1.0259 × 107 | 2.2493 × 108 | 2.6940 × 104 | 9.0162 × 104 | 2.0009 × 104 | 7.2421 × 109 | 5.8322 × 103 | |

| F14 | Ave | 6.0811 × 105 | 8.9041 × 106 | 3.9821 × 106 | 5.8826 × 106 | 1.4498 × 105 | 3.4243 × 105 | 6.5313 × 104 | 3.7417 × 104 | 4.2656 × 104 |

| Std | 4.4206 × 105 | 1.1458 × 107 | 1.9004 × 106 | 4.5658 × 106 | 1.4222 × 105 | 2.7049 × 105 | 5.9888 × 104 | 4.8767 × 104 | 2.9291 × 104 | |

| F15 | Ave | 4.0619 × 104 | 2.1122 × 107 | 1.1352 × 106 | 3.8551 × 107 | 1.3645 × 104 | 5.3867 × 104 | 1.4510 × 104 | 5.3517 × 107 | 1.1520 × 104 |

| Std | 2.3228 × 104 | 6.3243 × 107 | 1.8480 × 106 | 9.7499 × 107 | 6.6070 × 103 | 3.1235 × 104 | 5.5899 × 103 | 1.3081 × 108 | 6.0694 × 103 | |

| F16 | Ave | 3.7966 × 103 | 3.8958 × 103 | 4.9647 × 103 | 4.7601 × 103 | 4.5602 × 103 | 3.5355 × 103 | 3.5296 × 103 | 5.6611 × 103 | 2.8123 × 103 |

| Std | 5.5317 × 102 | 7.0550 × 102 | 2.6068 × 102 | 6.6489 × 102 | 3.0039 × 102 | 4.5633 × 102 | 3.5069 × 102 | 9.8291 × 102 | 3.9447 × 102 | |

| F17 | Ave | 3.5253 × 103 | 3.4156 × 103 | 3.6900 × 103 | 4.3774 × 103 | 3.4723 × 103 | 3.1505 × 103 | 3.4663 × 103 | 3.8770 × 103 | 2.5950 × 103 |

| Std | 3.8233 × 102 | 3.3934 × 102 | 2.0682 × 102 | 4.9180 × 102 | 1.9631 × 102 | 3.2729 × 102 | 2.8992 × 102 | 5.1077 × 102 | 2.1353 × 102 | |

| F18 | Ave | 4.2134 × 106 | 6.6806 × 106 | 2.3374 × 107 | 1.2352 × 107 | 2.4199 × 106 | 2.6121 × 106 | 1.2468 × 106 | 1.0159 × 106 | 4.8059 × 105 |

| Std | 2.8302 × 106 | 4.9074 × 106 | 9.2913 × 106 | 1.4539 × 107 | 1.0963 × 106 | 1.8049 × 106 | 9.8430 × 105 | 1.1779 × 106 | 5.1644 × 105 | |

| F19 | Ave | 1.2013 × 106 | 1.6232 × 104 | 6.3525 × 105 | 8.1998 × 106 | 1.8723 × 104 | 1.2200 × 106 | 2.9702 × 104 | 1.9072 × 107 | 1.7740 × 104 |

| Std | 1.5680 × 106 | 8.9557 × 103 | 9.5841 × 105 | 1.1849 × 107 | 5.5918 × 103 | 7.6072 × 105 | 4.6708 × 104 | 2.7724 × 107 | 8.1386 × 103 | |

| F20 | Ave | 3.2165 × 103 | 3.2702 × 103 | 3.7755 × 103 | 3.7526 × 103 | 3.6186 × 103 | 3.2645 × 103 | 3.2091 × 103 | 3.1639 × 103 | 2.7691 × 103 |

| Std | 2.9191 × 102 | 2.9951 × 102 | 1.7398 × 102 | 3.8260 × 102 | 1.7512 × 102 | 2.7182 × 102 | 3.0907 × 102 | 1.8463 × 102 | 2.0685 × 102 | |

| F21 | Ave | 2.6042 × 103 | 2.6411 × 103 | 2.7359 × 103 | 2.8660 × 103 | 2.7075 × 103 | 2.5513 × 103 | 2.8762 × 103 | 2.9289 × 103 | 2.4772 × 103 |

| Std | 6.4250 × 101 | 1.0573 × 102 | 2.1015 × 101 | 6.4780 × 101 | 2.1454 × 101 | 4.7574 × 101 | 3.7007 × 101 | 7.2025 × 101 | 5.6235 × 101 | |

| F22 | Ave | 9.6764 × 103 | 9.4864 × 103 | 1.5584 × 104 | 1.3208 × 104 | 1.2780 × 104 | 9.4708 × 103 | 9.6656 × 103 | 1.4005 × 104 | 7.8477 × 103 |

| Std | 8.5974 × 102 | 8.4512 × 102 | 5.8690 × 102 | 2.1911 × 103 | 5.2676 × 103 | 1.0315 × 103 | 1.0172 × 103 | 5.6818 × 102 | 5.0326 × 103 | |

| F23 | Ave | 3.0880 × 103 | 3.8443 × 103 | 3.1658 × 103 | 3.5568 × 103 | 3.1799 × 103 | 3.0555 × 103 | 3.2830 × 103 | 3.7363 × 103 | 2.9316 × 103 |

| Std | 7.9708 × 101 | 4.0113 × 102 | 2.2225 × 101 | 1.3755 × 102 | 2.6344 × 101 | 7.0657 × 101 | 3.7022 × 101 | 1.8000 × 102 | 5.9147 × 101 | |

| F24 | Ave | 3.2494 × 103 | 4.0540 × 103 | 3.3516 × 103 | 3.7382 × 103 | 3.3427 × 103 | 3.2264 × 103 | 3.3456 × 103 | 3.7743 × 103 | 3.0600 × 103 |

| Std | 6.4343 × 101 | 2.6734 × 102 | 1.8478 × 101 | 1.5889 × 102 | 3.2241 × 101 | 8.6094 × 101 | 1.8244 × 101 | 1.1511 × 102 | 5.4740 × 101 | |

| F25 | Ave | 3.3587 × 103 | 3.2885 × 103 | 3.1945 × 103 | 3.6633 × 103 | 3.2314 × 103 | 3.0988 × 103 | 3.7165 × 103 | 1.2572 × 104 | 3.0974 × 103 |

| Std | 1.1910 × 102 | 1.0461 × 102 | 4.7756 × 101 | 9.3379 × 102 | 6.4636 × 101 | 4.1665 × 101 | 2.4642 × 102 | 1.6156 × 103 | 3.0998 × 101 | |

| F26 | Ave | 8.0969 × 103 | 8.7493 × 103 | 8.0014 × 103 | 1.1317 × 104 | 8.0100 × 103 | 5.7871 × 103 | 7.9508 × 103 | 1.5517 × 104 | 3.3327 × 103 |

| Std | 2.0458 × 103 | 2.3274 × 103 | 2.3182 × 102 | 1.3982 × 103 | 1.9005 × 103 | 2.2161 × 103 | 5.6026 × 102 | 8.6294 × 102 | 9.9177 × 102 | |

| F27 | Ave | 3.7694 × 103 | 3.7798 × 103 | 3.5320 × 103 | 4.0281 × 103 | 3.7430 × 103 | 3.6255 × 103 | 3.7277 × 103 | 4.1103 × 103 | 3.4265 × 103 |

| Std | 1.3805 × 102 | 8.4163 × 102 | 8.4631 × 101 | 3.0138 × 102 | 9.0074 × 102 | 1.0779 × 102 | 1.4505 × 102 | 2.5652 × 102 | 7.6224 × 101 | |

| F28 | Ave | 3.8533 × 103 | 3.6211 × 103 | 4.9503 × 103 | 5.7094 × 103 | 3.6853 × 103 | 3.3839 × 103 | 5.0837 × 103 | 1.0372 × 104 | 3.3638 × 103 |

| Std | 1.4607 × 102 | 3.8148 × 102 | 6.3689 × 102 | 2.3421 × 103 | 9.7160 × 101 | 3.8751 × 101 | 1.4174 × 103 | 1.1033 × 103 | 2.6029 × 101 | |

| F29 | Ave | 5.4812 × 103 | 4.6897 × 103 | 5.5892 × 103 | 6.6335 × 103 | 5.2475 × 103 | 5.0831 × 103 | 5.4732 × 103 | 8.9046 × 103 | 4.0101 × 103 |

| Std | 4.0343 × 102 | 8.8628 × 102 | 2.9354 × 102 | 1.1993 × 103 | 1.8873 × 102 | 4.9784 × 102 | 3.3283 × 102 | 1.7655 × 103 | 3.3210 × 102 | |

| F30 | Ave | 1.2068 × 108 | 8.6313 × 107 | 3.7308 × 107 | 4.3751 × 107 | 9.8868 × 106 | 5.2689 × 107 | 4.5924 × 106 | 5.1042 × 108 | 9.2893 × 105 |

| Std | 4.2359 × 107 | 4.6330 × 108 | 1.4515 × 107 | 4.2792 × 107 | 3.9091 × 106 | 1.3199 × 107 | 2.5314 × 106 | 4.8616 × 108 | 1.6536 × 105 |

| Function | Metric | VPPSO | IAGWO | ADE | DBO | CPO | AOO | HSO | IAO | MEIAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Ave | 5.6690 × 106 | 1.7196 × 106 | 4.7848 × 106 | 2.5261 × 108 | 7.8801 × 105 | 8.4743 × 104 | 9.1857 × 103 | 4.1305 × 1010 | 3.9158 × 103 |

| Std | 5.1922 × 103 | 4.8156 × 103 | 5.0059 × 103 | 1.0102 × 104 | 4.9033 × 103 | 3.8247 × 103 | 6.3489 × 103 | 2.3789 × 104 | 3.5421 × 103 | |

| F2 | Ave | 1.6098 × 1023 | 1.4519 × 1033 | 2.9671 × 1032 | 1.7732 × 1032 | 5.3667 × 1023 | 3.3146 × 1016 | 1.2694 × 1016 | 2.9482 × 1037 | 1.9892 × 1012 |

| Std | 2.1868 × 104 | 2.0034 × 104 | 1.7116 × 104 | 2.7499 × 104 | 2.0874 × 104 | 1.6833 × 104 | 1.9302 × 104 | 4.7235 × 104 | 1.6872 × 104 | |

| F3 | Ave | 4.4098 × 104 | 5.5238 × 104 | 1.5964 × 105 | 9.5621 × 104 | 6.1922 × 104 | 2.8241 × 104 | 5.0767 × 104 | 5.6804 × 104 | 8.3114 × 103 |

| Std | 4.3680 × 103 | 5.5518 × 103 | 4.2199 × 103 | 4.7125 × 103 | 4.2334 × 103 | 4.0701 × 103 | 4.2874 × 103 | 7.0678 × 103 | 3.7045 × 103 | |

| F4 | Ave | 5.2585 × 102 | 6.1821 × 102 | 5.1202 × 102 | 6.4624 × 102 | 5.1317 × 102 | 5.0597 × 102 | 7.1004 × 102 | 8.1367 × 103 | 4.8202 × 102 |

| Std | 6.3830 × 103 | 6.6003 × 103 | 1.3796 × 104 | 1.9015 × 104 | 6.1584 × 103 | 3.9625 × 103 | 1.6191 × 103 | 2.9617 × 104 | 3.7709 × 103 | |

| F5 | Ave | 6.4802 × 102 | 6.5832 × 102 | 6.9209 × 102 | 7.3702 × 102 | 6.9559 × 102 | 6.2225 × 102 | 6.9554 × 102 | 7.8512 × 102 | 5.9882 × 102 |

| Std | 1.0476 × 104 | 8.3847 × 103 | 1.0550 × 104 | 1.2484 × 104 | 1.0421 × 104 | 8.8770 × 103 | 9.6508 × 103 | 7.4055 × 104 | 7.0258 × 103 | |

| F6 | Ave | 6.3982 × 102 | 6.2087 × 102 | 6.0086 × 102 | 6.5289 × 102 | 6.0195 × 102 | 6.2937 × 102 | 6.4985 × 102 | 6.6317 × 102 | 6.0005 × 102 |

| Std | 3.3951 × 108 | 2.6429 × 107 | 6.8209 × 106 | 2.7553 × 108 | 6.9930 × 106 | 1.0061 × 108 | 1.0931 × 106 | 2.5021 × 1010 | 2.9797 × 104 | |

| F7 | Ave | 1.7978 × 1010 | 3.3133 × 108 | 7.6767 × 109 | 9.0428 × 1010 | 1.4820 × 1010 | 4.4285 × 108 | 3.5998 × 109 | 2.4335 × 1011 | 1.4937 × 107 |

| Std | 2.9231 × 102 | 1.7159 × 102 | 4.7201 × 101 | 2.6920 × 102 | 9.4636 × 101 | 1.9180 × 102 | 6.8633 × 102 | 8.8044 × 101 | 2.2915 × 102 | |

| F8 | Ave | 2.3700 × 10137 | 5.9519 × 10147 | 6.9527 × 10154 | 1.3940 × 10154 | 1.2315 × 10127 | 1.1499 × 10121 | 4.4479 × 10203 | 1.2287 × 10162 | 3.3103 × 10100 |

| Std | 8.1577 × 101 | 9.6108 × 101 | 3.5696 × 101 | 2.2160 × 102 | 5.2495 × 101 | 1.0410 × 102 | 8.5140 × 101 | 5.6269 × 101 | 1.4726 × 102 | |

| F9 | Ave | 3.7350 × 105 | 4.4883 × 105 | 8.9415 × 105 | 6.1327 × 105 | 4.5035 × 105 | 5.6695 × 105 | 3.6573 × 105 | 3.0992 × 105 | 2.4388 × 105 |

| Std | 8.2326 × 103 | 8.0253 × 103 | 9.8626 × 103 | 1.3846 × 104 | 8.3235 × 103 | 6.2430 × 103 | 1.6184 × 104 | 2.6347 × 103 | 8.6674 × 103 | |

| F10 | Ave | 3.0095 × 103 | 2.5116 × 103 | 1.7042 × 103 | 1.4390 × 104 | 2.3712 × 103 | 1.0543 × 103 | 2.9120 × 103 | 8.0259 × 104 | 8.9797 × 102 |

| Std | 1.4641 × 103 | 3.1819 × 103 | 6.2813 × 102 | 3.9617 × 103 | 7.1984 × 102 | 1.3901 × 103 | 1.5560 × 103 | 9.1512 × 102 | 3.4596 × 103 | |

| F11 | Ave | 1.3096 × 103 | 1.2696 × 103 | 1.6462 × 103 | 1.7191 × 103 | 1.6712 × 103 | 1.2869 × 103 | 1.6704 × 103 | 1.9251 × 103 | 1.2139 × 103 |

| Std | 1.4987 × 104 | 3.0011 × 104 | 4.9925 × 104 | 5.0301 × 104 | 1.0434 × 104 | 9.5164 × 103 | 1.9748 × 104 | 2.5384 × 104 | 3.0207 × 103 | |

| F12 | Ave | 6.6497 × 102 | 6.4679 × 102 | 6.2132 × 102 | 6.7982 × 102 | 6.4497 × 102 | 6.6323 × 102 | 6.9137 × 102 | 6.9736 × 102 | 6.2753 × 102 |

| Std | 6.9959 × 108 | 1.1215 × 1010 | 8.6264 × 108 | 2.5333 × 109 | 2.5200 × 108 | 2.1755 × 108 | 1.0898 × 108 | 2.6480 × 1010 | 1.3446 × 107 | |

| F13 | Ave | 2.5910 × 103 | 2.2342 × 103 | 2.2206 × 103 | 2.9668 × 103 | 2.3386 × 103 | 2.0098 × 103 | 4.7302 × 103 | 3.7472 × 103 | 2.0735 × 103 |

| Std | 5.2972 × 105 | 8.3023 × 105 | 5.2156 × 104 | 3.1314 × 108 | 1.1030 × 105 | 2.3058 × 104 | 3.1488 × 104 | 9.4123 × 109 | 4.0211 × 103 | |

| F14 | Ave | 1.6638 × 103 | 1.6255 × 103 | 1.9413 × 103 | 2.1508 × 103 | 1.9688 × 103 | 1.5511 × 103 | 2.0353 × 103 | 2.3868 × 103 | 1.5650 × 103 |

| Std | 4.3543 × 106 | 1.9216 × 107 | 1.2905 × 107 | 1.5545 × 107 | 2.2461 × 106 | 2.5163 × 106 | 4.9783 × 105 | 8.8326 × 106 | 3.9481 × 105 | |

| F15 | Ave | 2.7534 × 104 | 3.9689 × 104 | 5.1638 × 104 | 7.2737 × 104 | 4.6521 × 104 | 3.5131 × 104 | 7.0463 × 104 | 6.1949 × 104 | 5.0296 × 104 |

| Std | 1.8066 × 104 | 3.4448 × 104 | 4.1437 × 106 | 8.7481 × 107 | 3.6041 × 103 | 2.3713 × 104 | 8.3190 × 103 | 4.9351 × 109 | 1.1407 × 103 | |

| F16 | Ave | 1.8072 × 104 | 1.6600 × 104 | 3.1780 × 104 | 2.9696 × 104 | 3.0286 × 104 | 1.7317 × 104 | 2.3907 × 104 | 2.7702 × 104 | 2.2987 × 104 |

| Std | 8.6796 × 102 | 1.7218 × 103 | 4.9578 × 102 | 1.4118 × 102 | 4.3846 × 102 | 7.8168 × 102 | 7.1273 × 102 | 2.5601 × 103 | 8.2026 × 102 | |

| F17 | Ave | 8.0967 × 104 | 7.8085 × 104 | 2.2940 × 105 | 2.1846 × 105 | 9.1490 × 104 | 3.2343 × 104 | 6.1448 × 104 | 1.3285 × 105 | 1.1484 × 104 |

| Std | 4.7880 × 102 | 1.8683 × 103 | 3.2764 × 102 | 1.2680 × 102 | 2.8908 × 102 | 7.0662 × 102 | 5.3539 × 102 | 1.0800 × 106 | 5.5410 × 102 | |

| F18 | Ave | 1.4614 × 109 | 5.3044 × 109 | 3.0583 × 109 | 7.4353 × 109 | 9.5192 × 108 | 5.4585 × 108 | 1.9414 × 108 | 1.6006 × 1011 | 3.1499 × 107 |

| Std | 2.7696 × 106 | 1.2957 × 107 | 1.9352 × 107 | 1.0814 × 107 | 2.4344 × 106 | 2.5672 × 106 | 1.6963 × 106 | 9.9620 × 106 | 8.9949 × 105 | |

| F19 | Ave | 1.5615 × 105 | 2.6928 × 105 | 6.2602 × 104 | 3.0290 × 108 | 1.6953 × 105 | 7.1327 × 104 | 7.0791 × 104 | 3.4108 × 1010 | 7.2444 × 103 |

| Std | 4.3290 × 106 | 2.0488 × 106 | 7.0696 × 106 | 5.1442 × 107 | 5.8977 × 103 | 3.6974 × 106 | 1.6547 × 104 | 5.9173 × 109 | 4.8000 × 103 | |

| F20 | Ave | 7.0768 × 106 | 1.1015 × 107 | 4.9378 × 107 | 2.3447 × 107 | 4.6312 × 106 | 4.1431 × 106 | 9.5770 × 105 | 1.2886 × 107 | 8.8474 × 105 |

| Std | 5.3028 × 102 | 7.3502 × 102 | 2.3404 × 102 | 7.2174 × 102 | 3.4744 × 102 | 7.0367 × 102 | 4.8199 × 102 | 3.6431 × 102 | 4.7898 × 102 | |

| F21 | Ave | 4.9077 × 104 | 1.7654 × 104 | 1.9195 × 106 | 7.2045 × 107 | 1.0036 × 104 | 5.6928 × 104 | 2.7150 × 104 | 1.2432 × 1010 | 2.8867 × 103 |

| Std | 1.1620 × 102 | 6.1443 × 102 | 3.9700 × 101 | 1.7188 × 102 | 3.9176 × 101 | 1.5024 × 102 | 6.6142 × 101 | 2.1564 × 102 | 1.6186 × 102 | |

| F22 | Ave | 7.8501 × 103 | 7.7264 × 103 | 1.1560 × 104 | 8.8447 × 103 | 1.0407 × 104 | 6.6807 × 103 | 7.1982 × 103 | 1.6782 × 104 | 5.6046 × 103 |

| Std | 1.5955 × 103 | 2.8640 × 103 | 5.6744 × 102 | 4.8342 × 103 | 8.6736 × 102 | 1.5331 × 103 | 1.5333 × 103 | 8.1040 × 102 | 3.4484 × 103 | |

| F23 | Ave | 5.4612 × 103 | 5.7910 × 103 | 8.1759 × 103 | 8.7964 × 103 | 6.9534 × 103 | 5.2932 × 103 | 5.8179 × 103 | 4.0521 × 105 | 4.6531 × 103 |

| Std | 1.6019 × 102 | 4.9816 × 102 | 2.6835 × 101 | 2.4749 × 102 | 5.8513 × 101 | 1.1703 × 102 | 5.5812 × 101 | 2.1985 × 102 | 1.2580 × 102 | |

| F24 | Ave | 5.4946 × 106 | 8.1914 × 106 | 7.8004 × 107 | 2.3205 × 107 | 5.5877 × 106 | 5.0969 × 106 | 2.3224 × 106 | 1.1806 × 107 | 1.7320 × 106 |

| Std | 1.6784 × 102 | 1.0848 × 103 | 4.3057 × 101 | 5.3511 × 102 | 8.4942 × 101 | 2.1033 × 102 | 6.1485 × 101 | 4.0603 × 102 | 1.4564 × 102 | |

| F25 | Ave | 6.1188 × 106 | 4.0726 × 105 | 3.7460 × 106 | 7.4385 × 107 | 1.2157 × 104 | 5.6183 × 106 | 2.2103 × 104 | 1.3578 × 1010 | 5.9315 × 103 |

| Std | 3.7382 × 102 | 9.4059 × 102 | 4.2328 × 102 | 6.1890 × 102 | 2.9881 × 102 | 1.1300 × 102 | 6.1602 × 102 | 2.6036 × 103 | 7.3012 × 101 | |

| F26 | Ave | 5.5012 × 103 | 5.3500 × 103 | 7.6557 × 103 | 7.3139 × 103 | 7.2926 × 103 | 5.3243 × 103 | 4.8285 × 103 | 6.0566 × 103 | 5.4152 × 103 |

| Std | 3.2313 × 103 | 4.9125 × 103 | 4.0132 × 102 | 3.8208 × 103 | 2.3566 × 103 | 2.5457 × 103 | 1.3165 × 103 | 3.9457 × 103 | 5.4463 × 103 | |

| F27 | Ave | 3.1911 × 103 | 4.1480 × 103 | 3.4659 × 103 | 4.0400 × 103 | 3.4105 × 103 | 3.1251 × 103 | 3.7284 × 103 | 4.3042 × 103 | 2.9183 × 103 |

| Std | 2.5994 × 102 | 2.4311 × 103 | 1.7101 × 102 | 4.2753 × 102 | 1.0196 × 102 | 1.9056 × 102 | 2.6173 × 102 | 7.9479 × 102 | 1.1751 × 102 | |

| F28 | Ave | 2.0844 × 104 | 2.0274 × 104 | 3.3890 × 104 | 2.8096 × 104 | 3.3137 × 104 | 2.0285 × 104 | 2.6034 × 104 | 3.0667 × 104 | 2.4171 × 104 |

| Std | 8.3988 × 102 | 3.2609 × 103 | 1.4842 × 103 | 6.7571 × 103 | 5.3220 × 102 | 1.4525 × 102 | 5.1755 × 103 | 2.9447 × 103 | 1.0270 × 102 | |

| F29 | Ave | 3.9181 × 103 | 5.9781 × 103 | 3.8044 × 103 | 4.8783 × 103 | 3.9781 × 103 | 3.7996 × 103 | 4.0205 × 103 | 5.0446 × 103 | 3.3238 × 103 |

| Std | 8.7950 × 102 | 3.4564 × 103 | 3.5979 × 102 | 2.6054 × 103 | 4.2379 × 102 | 8.6304 × 102 | 6.7551 × 102 | 8.7655 × 104 | 1.0112 × 103 | |

| F30 | Ave | 4.6572 × 103 | 6.7949 × 103 | 4.3381 × 103 | 6.2359 × 103 | 4.6052 × 103 | 4.5040 × 103 | 4.6155 × 103 | 6.8111 × 103 | 3.9364 × 103 |

| Std | 1.5405 × 108 | 6.8961 × 107 | 5.3159 × 106 | 1.2458 × 108 | 4.6625 × 106 | 5.0172 × 107 | 7.6097 × 105 | 9.6962 × 109 | 1.3147 × 104 |

| Function | Metric | VPPSO | IAGWO | ADE | DBO | CPO | AOO | HSO | IAO | MEIAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Ave | 3.2168 × 102 | 3.3363 × 102 | 5.8954 × 103 | 1.6761 × 103 | 4.1471 × 102 | 3.0000 × 102 | 1.3611 × 103 | 5.4721 × 102 | 3.0000 × 102 |

| Std | 6.2599 × 101 | 4.2545 × 101 | 1.7838 × 103 | 1.5598 × 103 | 1.0488 × 103 | 2.5488 × 103 | 2.7792 × 102 | 4.7759 × 102 | 3.6566 × 10-14 | |

| F2 | Ave | 4.0527 × 102 | 4.2743 × 102 | 4.0839 × 102 | 4.4200 × 102 | 4.0050 × 102 | 4.1174 × 102 | 4.5795 × 102 | 4.1428 × 102 | 4.1018 × 102 |

| Std | 3.9828 × 100 | 3.4439 × 101 | 6.5390 × 10-1 | 3.7532 × 101 | 1.7707 × 100 | 1.9706 × 101 | 3.0717 × 101 | 2.6762 × 101 | 2.0850 × 101 | |

| F3 | Ave | 6.0616 × 102 | 6.0035 × 102 | 6.0000 × 102 | 6.0921 × 102 | 6.0000 × 102 | 6.0309 × 102 | 6.2081 × 102 | 6.1610 × 102 | 6.0000 × 102 |

| Std | 6.0768 × 100 | 2.7822 × 10-1 | 4.9395 × 10-5 | 6.1258 × 100 | 2.6873 × 10-3 | 3.3009 × 100 | 5.3945 × 100 | 1.3370 × 101 | 5.9711 × 10-14 | |

| F4 | Ave | 8.1973 × 102 | 8.1941 × 102 | 8.2764 × 102 | 8.3537 × 102 | 8.2169 × 102 | 8.2017 × 102 | 8.3727 × 102 | 8.1426 × 102 | 8.1206 × 102 |

| Std | 7.2116 × 100 | 8.8887 × 100 | 5.7921 × 100 | 9.6418 × 100 | 7.5712 × 100 | 1.0092 × 101 | 5.6815 × 100 | 5.0031 × 100 | 3.9741 × 100 | |

| F5 | Ave | 9.1361 × 102 | 9.2470 × 102 | 9.0114 × 102 | 1.0207 × 103 | 9.0000 × 102 | 9.0140 × 102 | 9.0897 × 102 | 1.0090 × 103 | 9.0001 × 102 |

| Std | 1.4809 × 101 | 4.2927 × 101 | 1.5751 × 100 | 1.0652 × 102 | 5.2372 × 10−4 | 2.5050 × 100 | 5.8921 × 100 | 1.0629 × 102 | 3.0954 × 10-2 | |

| F6 | Ave | 3.9174 × 103 | 3.1520 × 103 | 1.0331 × 104 | 4.6301 × 103 | 1.8312 × 103 | 4.7186 × 103 | 2.8986 × 103 | 1.8167 × 103 | 1.8139 × 103 |

| Std | 2.2285 × 103 | 1.8163 × 103 | 1.1309 × 104 | 2.3130 × 103 | 1.3131 × 101 | 2.2416 × 103 | 1.2245 × 103 | 1.6198 × 101 | 1.7623 × 101 | |

| F7 | Ave | 2.0403 × 103 | 2.0145 × 103 | 2.0180 × 103 | 2.0389 × 103 | 2.0105 × 103 | 2.0311 × 103 | 2.0866 × 103 | 2.0243 × 103 | 2.0029 × 103 |

| Std | 1.1261 × 101 | 9.6462 × 100 | 2.2731 × 101 | 1.2469 × 101 | 3.9909 × 100 | 1.3549 × 101 | 4.0041 × 101 | 7.1685 × 100 | 6.8409 × 100 | |

| F8 | Ave | 2.2250 × 103 | 2.2214 × 103 | 2.2208 × 103 | 2.2273 × 103 | 2.2182 × 103 | 2.2245 × 103 | 2.2729 × 103 | 2.2161 × 103 | 2.2092 × 103 |

| Std | 2.6743 × 100 | 1.6564 × 100 | 3.3783 × 100 | 7.2016 × 100 | 5.4018 × 100 | 6.6343 × 100 | 5.3377 × 101 | 7.4940 × 100 | 1.0120 × 101 | |

| F9 | Ave | 2.5322 × 103 | 2.5235 × 103 | 2.5293 × 103 | 2.5647 × 103 | 2.5293 × 103 | 2.5296 × 103 | 2.6700 × 103 | 2.5294 × 103 | 2.5293 × 103 |

| Std | 3.9594 × 100 | 1.3844 × 101 | 3.5546 × 10-9 | 5.1862 × 101 | 5.8674 × 10-3 | 9.5669 × 10-1 | 5.3833 × 101 | 1.7476 × 10-1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| F10 | Ave | 2.5543 × 103 | 2.5675 × 103 | 2.5068 × 103 | 2.5465 × 103 | 2.5079 × 103 | 2.5717 × 103 | 2.5906 × 103 | 2.5207 × 103 | 2.5431 × 103 |

| Std | 5.9795 × 101 | 6.3640 × 101 | 4.3278 × 101 | 6.5626 × 101 | 2.8541 × 101 | 5.9419 × 101 | 8.7721 × 101 | 4.5297 × 101 | 5.3377 × 101 | |

| F11 | Ave | 2.7417 × 103 | 2.7819 × 103 | 2.6556 × 103 | 2.7471 × 103 | 2.6100 × 103 | 2.7438 × 103 | 2.9888 × 103 | 2.6931 × 103 | 2.6451 × 103 |

| Std | 1.5870 × 102 | 1.4802 × 102 | 8.4670 × 101 | 1.1445 × 102 | 5.4772 × 101 | 1.6996 × 102 | 1.7852 × 102 | 6.0740 × 101 | 8.0412 × 101 | |

| F12 | Ave | 2.8639 × 103 | 2.8761 × 103 | 2.8621 × 103 | 2.8803 × 103 | 2.8652 × 103 | 2.8644 × 103 | 2.8654 × 103 | 2.8645 × 103 | 2.8640 × 103 |

| Std | 1.6534 × 100 | 1.8398 × 101 | 1.1115 × 100 | 2.1065 × 101 | 6.3100 × 10-1 | 1.6864 × 100 | 6.6547 × 10-1 | 4.7233 × 100 | 1.5169 × 100 |

| Function | Metric | VPPSO | IAGWO | ADE | DBO | CPO | AOO | HSO | IAO | MEIAO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Ave | 6.5543 × 103 | 1.0835 × 104 | 3.8147 × 104 | 3.2232 × 104 | 1.2744 × 104 | 4.3297 × 102 | 6.8820 × 103 | 1.4897 × 104 | 3.3565 × 102 |

| Std | 1.8431 × 103 | 5.5483 × 103 | 8.4294 × 103 | 9.4330 × 103 | 2.9612 × 103 | 1.3231 × 102 | 2.5856 × 103 | 5.8017 × 103 | 6.1709 × 101 | |

| F2 | Ave | 4.7581 × 102 | 5.0561 × 102 | 4.4919 × 102 | 5.1620 × 102 | 4.6022 × 102 | 4.5580 × 102 | 5.6638 × 102 | 1.2156 × 103 | 4.5363 × 102 |

| Std | 2.6686 × 101 | 4.5224 × 101 | 8.6818 × 10-1 | 8.5701 × 101 | 1.0060 × 101 | 1.4796 × 101 | 6.8939 × 101 | 4.3948 × 102 | 1.0233 × 101 | |

| F3 | Ave | 6.2761 × 102 | 6.0829 × 102 | 6.0008 × 102 | 6.3927 × 102 | 6.0028 × 102 | 6.1992 × 102 | 6.3864 × 102 | 6.4093 × 102 | 6.0000 × 102 |

| Std | 1.0718 × 101 | 4.7481 × 100 | 3.7449 × 10-2 | 1.2786 × 101 | 1.2220 × 10-1 | 9.7333 × 100 | 5.6199 × 100 | 1.1421 × 101 | 1.2882 × 10-2 | |

| F4 | Ave | 8.6230 × 102 | 8.6643 × 102 | 9.2339 × 102 | 9.0847 × 102 | 9.0096 × 102 | 8.5917 × 102 | 9.1754 × 102 | 9.0095 × 102 | 8.5427 × 102 |

| Std | 1.3695 × 101 | 1.4935 × 101 | 1.0628 × 101 | 2.6827 × 101 | 1.1714 × 101 | 1.7879 × 101 | 1.3213 × 101 | 1.5451 × 101 | 1.7459 × 101 | |

| F5 | Ave | 1.5134 × 103 | 1.9573 × 103 | 1.2336 × 103 | 2.3248 × 103 | 9.1434 × 102 | 1.5537 × 103 | 1.0635 × 103 | 2.3032 × 103 | 9.0814 × 102 |

| Std | 3.2544 × 102 | 3.7329 × 102 | 2.0725 × 102 | 6.2570 × 102 | 2.2688 × 101 | 5.9480 × 102 | 1.2964 × 102 | 3.0970 × 102 | 2.5962 × 101 | |

| F6 | Ave | 4.9920 × 103 | 7.7143 × 104 | 4.2204 × 106 | 5.9065 × 105 | 2.1873 × 104 | 7.1835 × 103 | 5.5208 × 103 | 3.7837 × 103 | 3.4377 × 103 |

| Std | 3.9015 × 103 | 3.9514 × 105 | 3.9845 × 106 | 1.8653 × 106 | 1.3430 × 104 | 5.6283 × 103 | 4.9803 × 103 | 4.3095 × 103 | 2.0434 × 103 | |

| F7 | Ave | 2.1005 × 103 | 2.0837 × 103 | 2.0618 × 103 | 2.1459 × 103 | 2.0667 × 103 | 2.0946 × 103 | 2.1413 × 103 | 2.0866 × 103 | 2.0359 × 103 |

| Std | 2.8652 × 101 | 4.9647 × 101 | 1.0807 × 101 | 4.7548 × 101 | 8.8900 × 100 | 5.1495 × 101 | 4.1290 × 101 | 2.5467 × 101 | 8.7726 × 100 | |

| F8 | Ave | 2.2548 × 103 | 2.2679 × 103 | 2.2322 × 103 | 2.3215 × 103 | 2.2318 × 103 | 2.2483 × 103 | 2.4723 × 103 | 2.2352 × 103 | 2.2274 × 103 |

| Std | 4.6085 × 101 | 5.7438 × 101 | 2.3511 × 100 | 6.7093 × 101 | 1.7625 × 100 | 4.1721 × 101 | 1.3237 × 102 | 2.1469 × 101 | 2.0985 × 100 | |

| F9 | Ave | 2.5070 × 103 | 2.4962 × 103 | 2.4808 × 103 | 2.5110 × 103 | 2.4816 × 103 | 2.4823 × 103 | 2.7344 × 103 | 2.5965 × 103 | 2.4808 × 103 |

| Std | 1.7498 × 101 | 1.1589 × 101 | 2.0895 × 10-2 | 3.0914 × 101 | 3.6710 × 10−1 | 1.9459 × 100 | 1.3520 × 102 | 4.2309 × 101 | 1.5659 × 10-9 | |

| F10 | Ave | 3.2240 × 103 | 2.7226 × 103 | 2.6443 × 103 | 3.5634 × 103 | 2.5322 × 103 | 3.3717 × 103 | 3.6955 × 103 | 3.4294 × 103 | 2.5428 × 103 |

| Std | 8.6657 × 102 | 2.5254 × 102 | 1.8854 × 102 | 1.2729 × 103 | 7.1730 × 101 | 8.8666 × 102 | 6.5891 × 102 | 1.2082 × 103 | 6.0402 × 101 | |

| F11 | Ave | 2.9494 × 103 | 2.9018 × 103 | 2.9103 × 103 | 3.1460 × 103 | 2.9152 × 103 | 2.9463 × 103 | 3.5900 × 103 | 5.7796 × 103 | 2.9333 × 103 |

| Std | 1.5379 × 102 | 1.2195 × 102 | 5.2174 × 101 | 1.6539 × 102 | 7.4140 × 101 | 8.9500 × 101 | 2.2898 × 102 | 1.0570 × 103 | 4.7946 × 101 | |

| F12 | Ave | 2.9799 × 103 | 2.9970 × 103 | 2.9463 × 103 | 3.0363 × 103 | 2.9904 × 103 | 2.9674 × 103 | 3.0093 × 103 | 3.0084 × 103 | 2.9471 × 103 |

| Std | 3.4548 × 101 | 1.8772 × 102 | 3.4108 × 100 | 7.2142 × 101 | 1.1640 × 101 | 1.9073 × 101 | 3.6148 × 101 | 4.5843 × 101 | 9.0538 × 100 |

| Statistical Results | CEC2017 dim = 30 (+/=/−) | CEC2017 dim = 50 (+/=/−) | CEC2017 dim = 100 (+/=/−) | CEC2022 dim = 10 (+/=/−) | CEC2022 dim = 20 (+/=/−) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPPSO | (29/0/1) | (27/0/3) | (29/0/1) | (11/0/1) | (11/0/1) |

| IAGWO | (28/0/2) | (23/0/7) | (27/0/3) | (9/0/3) | (11/0/1) |

| ADE | (30/0/0) | (30/0/0) | (28/0/2) | (11/0/1) | (11/0/1) |

| DBO | (28/0/2) | (30/0/0) | (30/0/0) | (12/0/0) | (12/0/0) |

| CPO | (29/0/1) | (28/0/2) | (30/0/0) | (11/0/1) | (12/0/0) |

| AOO | (28/0/2) | (24/1/5) | (27/0/3) | (11/0/1) | (11/0/1) |

| HSO | (30/0/0) | (25/0/5) | (26/0/4) | (12/0/0) | (12/0/0) |

| IAO | (29/0/1) | (30/0/0) | (30/0/0) | (9/0/3) | (11/0/1) |

| Suites | CEC2017 | CEC2022 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | 30 | 50 | 100 | 10 | 20 | |||||

| Algorithms | ||||||||||

| VPPSO | 4.77 | 4 | 5.03 | 6 | 4.97 | 4 | 5.08 | 6 | 4.58 | 5 |

| IAGWO | 4.93 | 5 | 4.23 | 3 | 3.83 | 3 | 4.83 | 5 | 4.50 | 4 |

| ADE | 6.10 | 7 | 6.27 | 7 | 5.67 | 7 | 4.58 | 4 | 4.33 | 2 |

| DBO | 7.50 | 9 | 7.47 | 8 | 7.60 | 8 | 7.75 | 8 | 7.25 | 8 |

| CPO | 4.00 | 3 | 4.67 | 4 | 5.23 | 6 | 3.25 | 2 | 4.42 | 3 |

| AOO | 3.80 | 2 | 3.37 | 2 | 3.00 | 2 | 5.33 | 7 | 4.58 | 5 |

| HSO | 5.53 | 6 | 4.77 | 5 | 4.97 | 4 | 8.33 | 9 | 7.25 | 8 |

| IAO | 7.13 | 8 | 7.80 | 9 | 8.13 | 9 | 4.42 | 3 | 6.92 | 7 |

| MEIAO | 1.23 | 1 | 1.40 | 1 | 1.60 | 1 | 1.42 | 1 | 1.17 | 1 |

| Algorithms | Best | Worst | Ave | Std | Runtime | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPPSO | 228.5646 | 419.7554 | 320.0495 | 93.5191 | 32.04 | 4 |

| IAGWO | 229.0077 | 379.7949 | 293.8463 | 74.8595 | 37.55 | 5 |

| ADE | 228.5803 | 439.9006 | 329.5800 | 88.9737 | 21.15 | 6 |

| DBO | 228.5841 | 640.8841 | 390.1997 | 85.4581 | 20.75 | 7 |

| CPO | 228.5729 | 412.8294 | 260.8809 | 62.8379 | 21.72 | 2 |

| AOO | 228.6922 | 566.9219 | 404.1177 | 66.8448 | 20.91 | 9 |

| HSO | 228.7660 | 862.2279 | 473.9606 | 176.5604 | 21.36 | 8 |

| IAO | 228.5642 | 412.7906 | 341.9324 | 72.5110 | 21.10 | 3 |

| MEIAO | 228.5641 | 412.7769 | 253.9190 | 60.6960 | 21.13 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Sun, R.; Zheng, J.; Shao, Y.; Zhou, H. MEIAO: A Multi-Strategy Enhanced Information Acquisition Optimizer for Global Optimization and UAV Path Planning. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10110765

Chen Y, Sun R, Zheng J, Shao Y, Zhou H. MEIAO: A Multi-Strategy Enhanced Information Acquisition Optimizer for Global Optimization and UAV Path Planning. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(11):765. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10110765

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yongzheng, Ruibo Sun, Jun Zheng, Yuanyuan Shao, and Haoxiang Zhou. 2025. "MEIAO: A Multi-Strategy Enhanced Information Acquisition Optimizer for Global Optimization and UAV Path Planning" Biomimetics 10, no. 11: 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10110765

APA StyleChen, Y., Sun, R., Zheng, J., Shao, Y., & Zhou, H. (2025). MEIAO: A Multi-Strategy Enhanced Information Acquisition Optimizer for Global Optimization and UAV Path Planning. Biomimetics, 10(11), 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10110765