The Marriage Behavior of the Greek Population from 1991 to 2021: A Study Through Gross Nuptiality Tables

Abstract

1. Introduction

Hypotheses

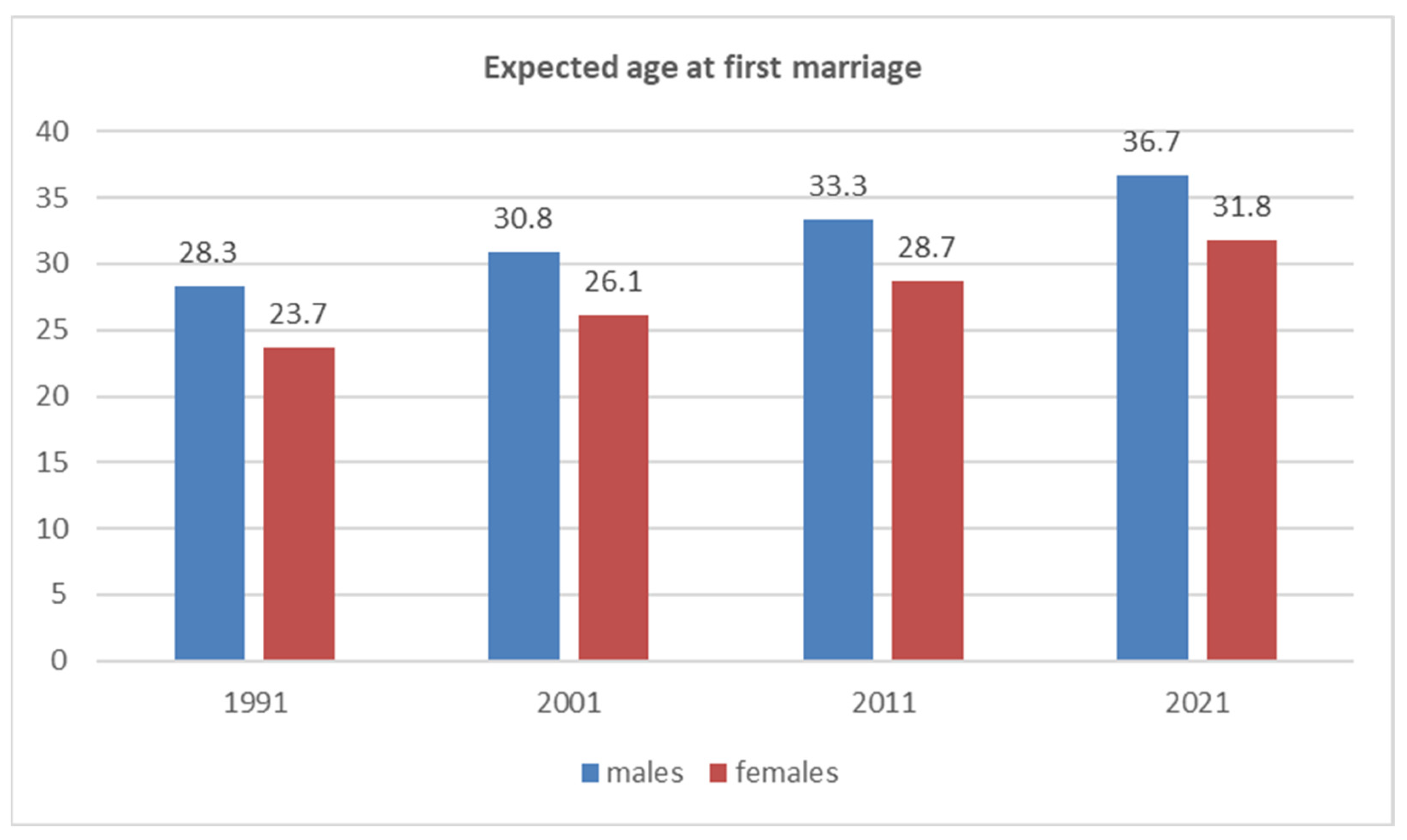

- It is anticipated that age at first marriage has significantly increased for both sexes in Greece from 1991 to 2021, with a more pronounced delay observed among females. This hypothesis is based on the inspection of the Singulate Mean Age at Marriage (SMAM), as this was derived by census returns (Gavalas 2025).

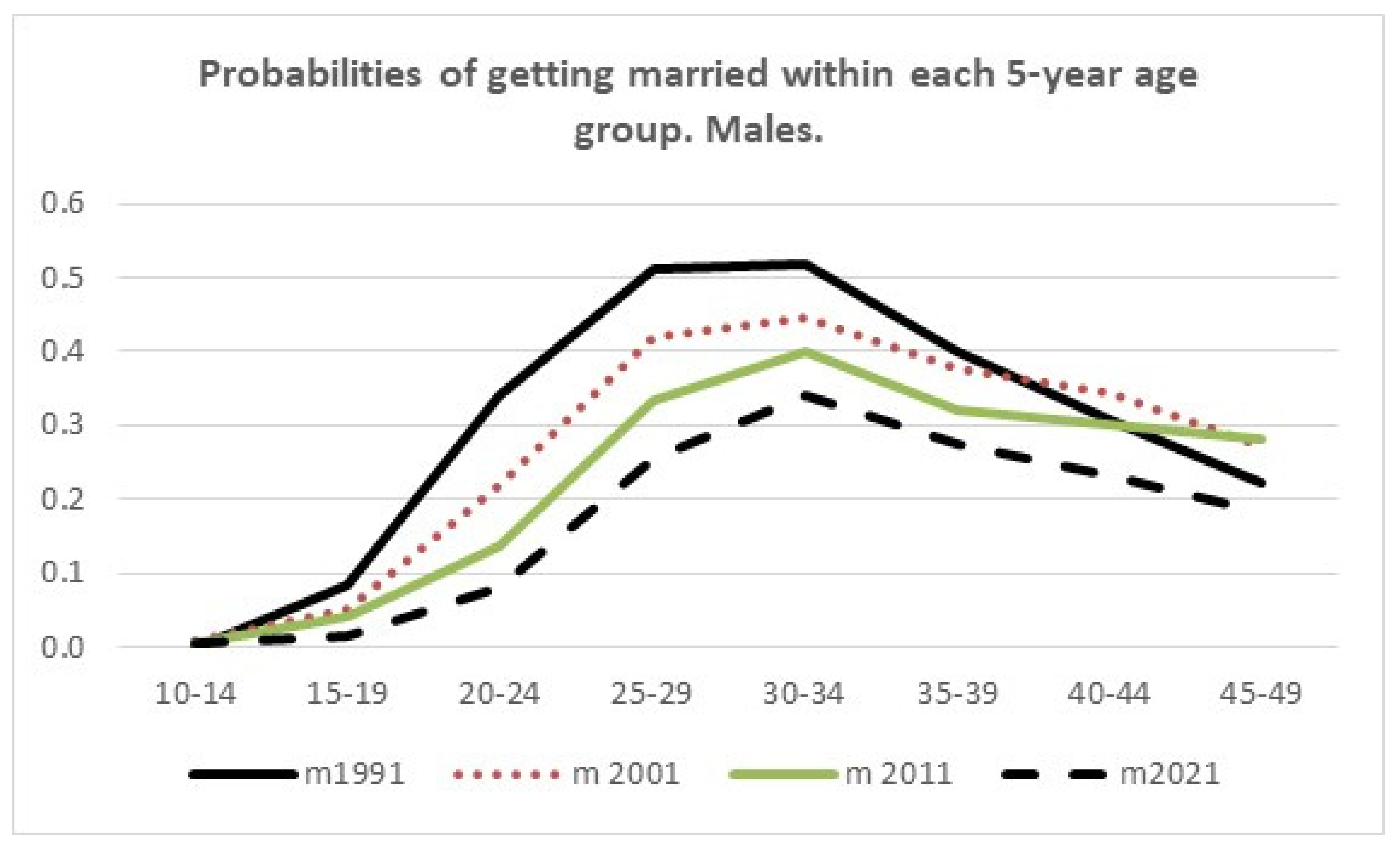

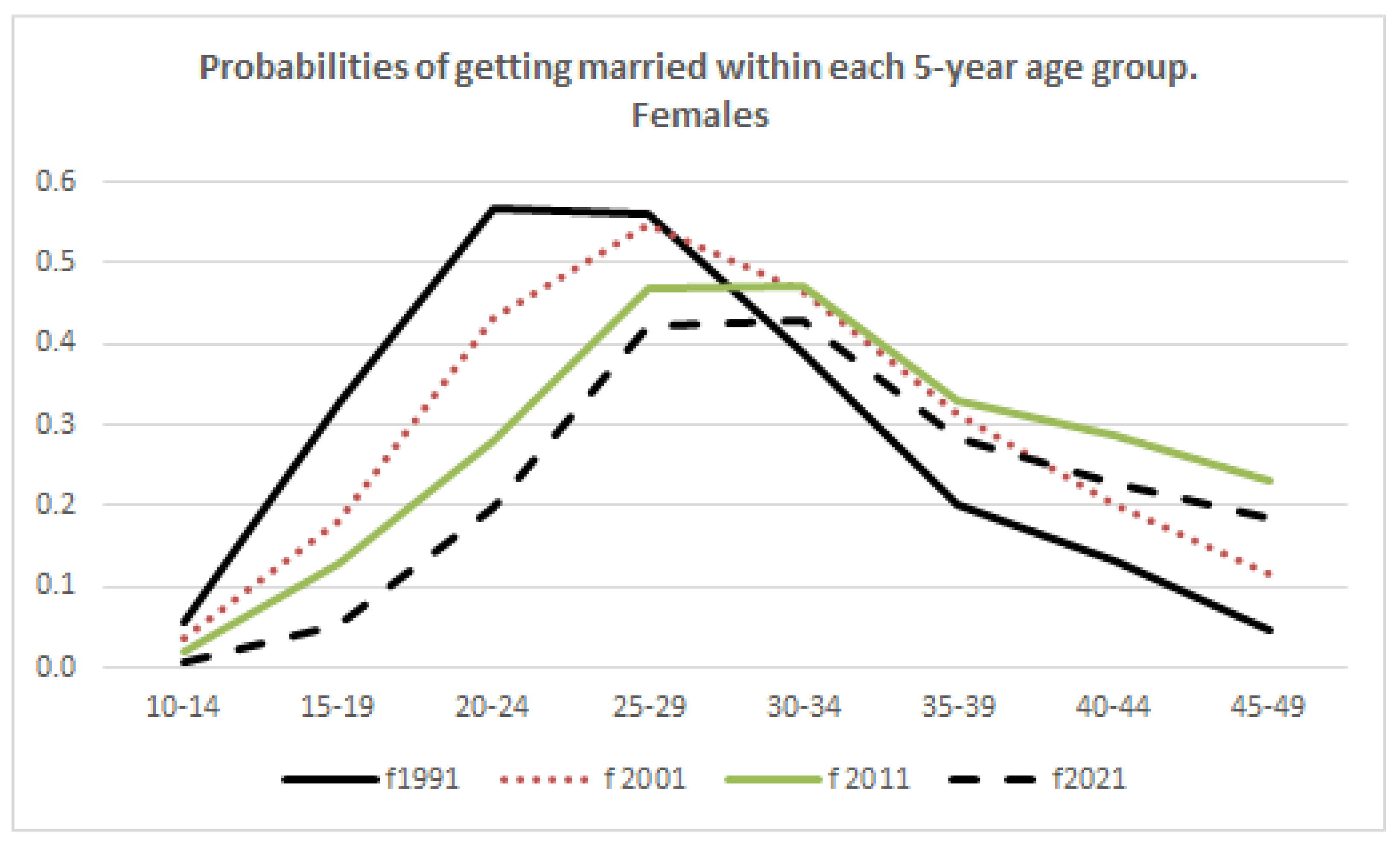

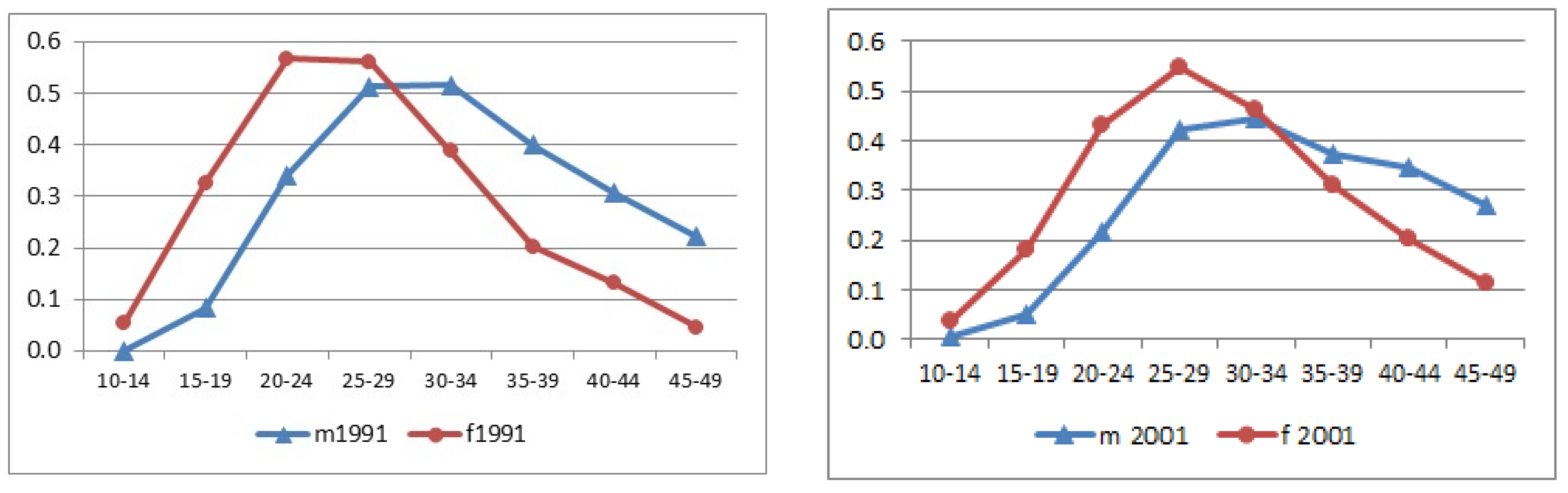

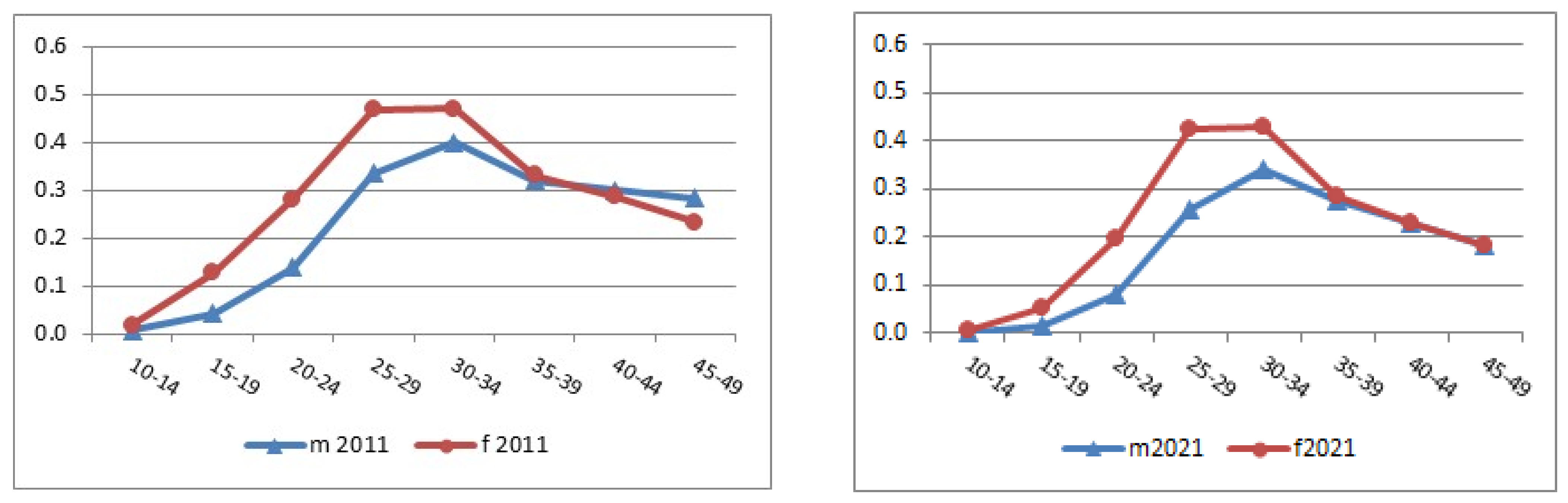

- A notable shift in age-specific marriage probabilities is expected, with a decline in marriage rates at younger ages and an initial increase at older ages. Yet, it remains to be seen if this increased probability of marrying at older ages persisted from 1991 all the way to 2021 and whether this is true for both sexes.

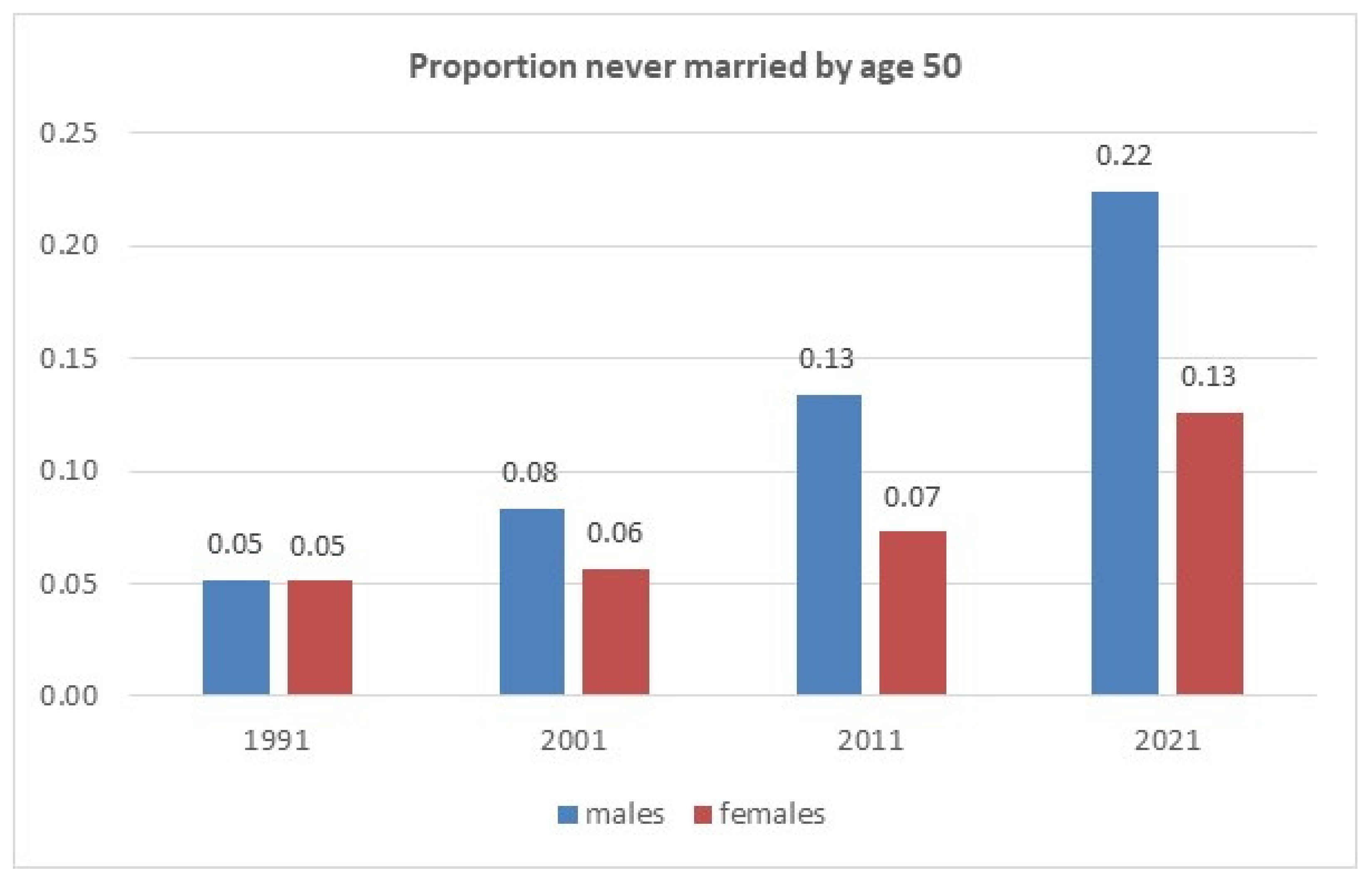

- It is expected that the proportion of individuals remaining permanently single (never married by age 50) has significantly increased between 1991 and 2021, with a substantially higher increase observed among males compared to females. Analysis of census data regarding permanent celibacy supports this trend (Gavalas 2025).

- (1)

- Cohort tables;

- (2)

- Period tables.

- (1)

- Full tables;

- (2)

- Abridged tables.

- (1)

- Net tables;

- (2)

- Gross tables.

2. Data and Methods

- nPx: Population (of each sex) from age x to age x + n.

- nPCx: Single population (of one sex) from age x to age x + n.

- nmx = Cx − Cx+n

- nnx = nmx/Cx

- nLx = (n · Cx+n) + (nαx · nmx)

- Tx = Τx+n + nLx with initial condition Τω= ∞ Lχ;

- ex = Tx/Cx.

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Males 1991 | ||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) |

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 286,143 | 286,143 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 2,832,088 | 28.3 |

| 5 | 5 | 341,078 | 341,078 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 2,332,088 | 23.3 |

| 10 | 5 | 387,720 | 387,720 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 1,832,088 | 18.3 |

| 15 | 5 | 394,647 | 392,289 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 8387 | 0.084 | 479,032 | 1,332,088 | 13.3 |

| 20 | 5 | 399,821 | 366,288 | 2.5 | 91,613 | 31,335 | 0.342 | 379,726 | 853,056 | 9.3 |

| 25 | 5 | 359,353 | 216,609 | 2.5 | 60,277 | 30,908 | 0.513 | 224,118 | 473,329 | 7.9 |

| 30 | 5 | 361,163 | 106,072 | 2.5 | 29,370 | 15,181 | 0.517 | 108,895 | 249,212 | 8.5 |

| 35 | 5 | 342,078 | 48,536 | 2.5 | 14,189 | 5680 | 0.400 | 56,742 | 140,316 | 9.9 |

| 40 | 5 | 336,449 | 28,626 | 2.5 | 8508 | 2609 | 0.307 | 36,018 | 83,574 | 9.8 |

| 45 | 5 | 278,589 | 16,434 | 2.5 | 5899 | 1314 | 0.223 | 26,210 | 47,556 | 8.1 |

| 50 | 5 | 319,255 | 14,638 | 2.5 | 4585 | 632 | 0.138 | 21,346 | 21,346 | 4.7 |

| Females 1991 | ||||||||||

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 270,844 | 270,844 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 2,366,723 | 23.7 |

| 5 | 5 | 322,356 | 322,356 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 1,866,723 | 18.7 |

| 10 | 5 | 366,726 | 366,406 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 5532 | 0.055 | 486,171 | 1,366,723 | 13.7 |

| 15 | 5 | 371,958 | 351,383 | 2.5 | 94,468 | 30,797 | 0.326 | 395,351 | 880,552 | 9.3 |

| 20 | 5 | 391,591 | 249,333 | 2.5 | 63,672 | 36,159 | 0.568 | 227,962 | 485,201 | 7.6 |

| 25 | 5 | 362,398 | 99,707 | 2.5 | 27,513 | 15,441 | 0.561 | 98,963 | 257,239 | 9.3 |

| 30 | 5 | 367,777 | 44,399 | 2.5 | 12,072 | 4687 | 0.388 | 48,643 | 158,276 | 13.1 |

| 35 | 5 | 339,238 | 25,052 | 2.5 | 7385 | 1497 | 0.203 | 33,182 | 109,633 | 14.8 |

| 40 | 5 | 336,802 | 19,831 | 2.5 | 5888 | 777 | 0.132 | 27,498 | 76,451 | 13.0 |

| 45 | 5 | 281,374 | 14,381 | 2.5 | 5111 | 235 | 0.046 | 24,967 | 48,953 | 9.6 |

| 50 | 5 | 338,060 | 17,292 | 2.5 | 4876 | 157 | 0.032 | 23,987 | 23,987 | 4.9 |

| Males 2001 | ||||||||||

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 271,741 | 271,741 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 3,083,226 | 30.8 |

| 5 | 5 | 280,959 | 280,959 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 2,583,226 | 25.8 |

| 10 | 5 | 306,063 | 306,028 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 820 | 0.008 | 497,950 | 2,083,226 | 20.8 |

| 15 | 5 | 381,964 | 378,832 | 2.5 | 99,180 | 5224 | 0.053 | 482,840 | 1,585,276 | 16.0 |

| 20 | 5 | 437,659 | 411,206 | 2.5 | 93,956 | 20,559 | 0.219 | 418,382 | 1,102,437 | 11.7 |

| 25 | 5 | 437,801 | 321,332 | 2.5 | 73,397 | 30,864 | 0.421 | 289,823 | 684,055 | 9.3 |

| 30 | 5 | 443,373 | 188,577 | 2.5 | 42,532 | 18,997 | 0.447 | 165,170 | 394,232 | 9.3 |

| 35 | 5 | 393,459 | 92,603 | 2.5 | 23,536 | 8837 | 0.375 | 95,585 | 229,062 | 9.7 |

| 40 | 5 | 388,367 | 57,083 | 2.5 | 14,698 | 5070 | 0.345 | 60,817 | 133,478 | 9.1 |

| 45 | 5 | 356,414 | 34,317 | 2.5 | 9628 | 2613 | 0.271 | 41,610 | 72,661 | 7.5 |

| 50 | 5 | 338,470 | 23,746 | 2.5 | 7016 | 1611 | 0.230 | 31,051 | 31,051 | 4.4 |

| Females 2001 | ||||||||||

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 258,528 | 258,528 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 500,000 | 2,612,732 | 26.1 |

| 5 | 5 | 265,055 | 265,055 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0.000 | 508,951 | 2,112,732 | 21.1 |

| 10 | 5 | 281,739 | 281,404 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 3580 | 0.036 | 526,140 | 1,603,781 | 16.0 |

| 15 | 5 | 346,954 | 334,532 | 2.5 | 96,420 | 17,617 | 0.183 | 478,943 | 1,077,641 | 11.2 |

| 20 | 5 | 398,743 | 314,222 | 2.5 | 78,803 | 33,971 | 0.431 | 285,365 | 598,698 | 7.6 |

| 25 | 5 | 412,286 | 184,837 | 2.5 | 44,832 | 24,481 | 0.546 | 125,324 | 313,334 | 7.0 |

| 30 | 5 | 429,698 | 87,447 | 2.5 | 20,351 | 9428 | 0.463 | 63,152 | 188,010 | 9.2 |

| 35 | 5 | 392,394 | 42,861 | 2.5 | 10,923 | 3415 | 0.313 | 41,340 | 124,858 | 11.4 |

| 40 | 5 | 395,530 | 29,696 | 2.5 | 7508 | 1520 | 0.202 | 31,670 | 83,518 | 11.1 |

| 45 | 5 | 359,063 | 21,500 | 2.5 | 5988 | 692 | 0.116 | 27,739 | 51,848 | 8.7 |

| 50 | 5 | 350,741 | 18,573 | 2.5 | 5295 | 505 | 0.095 | 24,108 | 24,108 | 4.6 |

| Males 2011 | ||||||||||

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 274,788 | 274,788 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 3,333,589 | 33.3 |

| 5 | 5 | 262,432 | 262,432 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 2,833,589 | 28.3 |

| 10 | 5 | 265,787 | 265,744 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 642 | 0.0064 | 498,395 | 2,333,589 | 23.3 |

| 15 | 5 | 286,386 | 284,547 | 2.5 | 99,358 | 4185 | 0.0421 | 486,328 | 1,835,194 | 18.5 |

| 20 | 5 | 325,127 | 309,434 | 2.5 | 95,173 | 13,199 | 0.1387 | 442,869 | 1,348,866 | 14.2 |

| 25 | 5 | 371,617 | 304,631 | 2.5 | 81,974 | 27,420 | 0.3345 | 341,322 | 905,997 | 11.1 |

| 30 | 5 | 417,861 | 227,961 | 2.5 | 54,554 | 21,832 | 0.4002 | 218,191 | 564,675 | 10.4 |

| 35 | 5 | 409,681 | 134,056 | 2.5 | 32,722 | 10,483 | 0.3204 | 137,403 | 346,484 | 10.6 |

| 40 | 5 | 414,026 | 92,076 | 2.5 | 22,239 | 6685 | 0.3006 | 94,485 | 209,081 | 9.4 |

| 45 | 5 | 367,086 | 57,099 | 2.5 | 15,555 | 4391 | 0.2823 | 66,795 | 114,597 | 7.4 |

| 50 | 5 | 355,552 | 39,691 | 2.5 | 11,163 | 3206 | 0.2872 | 47,802 | 47,802 | 4.3 |

| Females 2011 | ||||||||||

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 262,455 | 262,455 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 2,869,760 | 28.7 |

| 5 | 5 | 250,164 | 250,164 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 2,369,760 | 23.7 |

| 10 | 5 | 253,642 | 253,431 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 1883 | 0.0188 | 495,293 | 1,869,760 | 18.7 |

| 15 | 5 | 266,890 | 261,865 | 2.5 | 98,117 | 12,592 | 0.1283 | 459,106 | 1,374,467 | 14.0 |

| 20 | 5 | 301,970 | 258,261 | 2.5 | 85,525 | 24,099 | 0.2818 | 367,379 | 915,361 | 10.7 |

| 25 | 5 | 352,154 | 216,315 | 2.5 | 61,426 | 28,734 | 0.4678 | 235,295 | 547,982 | 8.9 |

| 30 | 5 | 404,614 | 132,276 | 2.5 | 32,692 | 15,360 | 0.4698 | 125,060 | 312,687 | 9.6 |

| 35 | 5 | 403,148 | 69,874 | 2.5 | 17,332 | 5742 | 0.3313 | 72,304 | 187,627 | 10.8 |

| 40 | 5 | 418,640 | 48,519 | 2.5 | 11,590 | 3328 | 0.2872 | 49,628 | 115,322 | 10.0 |

| 45 | 5 | 381,343 | 31,504 | 2.5 | 8261 | 1920 | 0.2324 | 36,507 | 65,695 | 8.0 |

| 50 | 5 | 375,934 | 23,839 | 2.5 | 6341 | 1007 | 0.1588 | 29,188 | 29,188 | 4.6 |

| Males 2021 | ||||||||||

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 212,295 | 212,295 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 3,668,928 | 36.7 |

| 5 | 5 | 239,198 | 239,198 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 3,168,928 | 31.7 |

| 10 | 5 | 277,154 | 277,111 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 411 | 0.0041 | 498,974 | 2,668,928 | 26.7 |

| 15 | 5 | 273,992 | 272,867 | 2.5 | 99,589 | 1445 | 0.0145 | 494,336 | 2,169,955 | 21.8 |

| 20 | 5 | 270,924 | 265,898 | 2.5 | 98,145 | 8046 | 0.0820 | 470,610 | 1,675,619 | 17.1 |

| 25 | 5 | 276,007 | 248,680 | 2.5 | 90,099 | 22,987 | 0.2551 | 393,029 | 1,205,009 | 13.4 |

| 30 | 5 | 289,196 | 194,086 | 2.5 | 67,112 | 22,941 | 0.3418 | 278,209 | 811,980 | 12.1 |

| 35 | 5 | 344,715 | 152,265 | 2.5 | 44,171 | 12,098 | 0.2739 | 190,612 | 533,771 | 12.1 |

| 40 | 5 | 397,884 | 127,615 | 2.5 | 32,073 | 7402 | 0.2308 | 141,863 | 343,160 | 10.7 |

| 45 | 5 | 399,840 | 98,648 | 2.5 | 24,672 | 4483 | 0.1817 | 112,153 | 201,296 | 8.2 |

| 50 | 5 | 397,358 | 80,224 | 2.5 | 20,189 | 4721 | 0.2339 | 89,143 | 89,143 | 4.4 |

| Females 2021 | ||||||||||

| x | n | nPx | nPCx | nax | Cx | nmx | nnx | nLx | Tx | ex |

| 0 | 5 | 200,460 | 200,460 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 3,177,554 | 31.8 |

| 5 | 5 | 226,545 | 226,545 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 0 | 0 | 500,000 | 2,677,554 | 26.8 |

| 10 | 5 | 261,334 | 261,278 | 2.5 | 100,000 | 695 | 0.0069 | 498,263 | 2,177,554 | 21.8 |

| 15 | 5 | 255,736 | 253,959 | 2.5 | 99,305 | 5103 | 0.0514 | 483,767 | 1,679,292 | 16.9 |

| 20 | 5 | 249,698 | 235,220 | 2.5 | 94,202 | 18,544 | 0.1969 | 424,649 | 1,195,524 | 12.7 |

| 25 | 5 | 256,678 | 194,197 | 2.5 | 75,658 | 31,955 | 0.4224 | 298,401 | 770,875 | 10.2 |

| 30 | 5 | 280,403 | 122,543 | 2.5 | 43,702 | 18,691 | 0.4277 | 171,786 | 472,474 | 10.8 |

| 35 | 5 | 342,078 | 85,560 | 2.5 | 25,012 | 7079 | 0.2830 | 107,362 | 300,689 | 12.0 |

| 40 | 5 | 396,429 | 71,091 | 2.5 | 17,933 | 4080 | 0.2275 | 79,464 | 193,327 | 10.8 |

| 45 | 5 | 401,880 | 55,671 | 2.5 | 13,853 | 2542 | 0.1835 | 62,908 | 113,863 | 8.2 |

| 50 | 5 | 409,770 | 46,348 | 2.5 | 11,311 | 2240 | 0.1980 | 50,955 | 50,955 | 4.5 |

| 1 | All decrement tables, either life tables or nuptiality tables, refer to a stationary population, the radix of which is a power of 10 (usually 1000 or 10,000 or 100,000). |

| 2 | The term primary nuptiality refers to first marriages. |

| 3 | Especially in our data, the Greek population has more numerous cohorts at older ages because of the declining fertility rates, which characterize Greece since the mid-1970s. |

| 4 | In nuptiality table terminology, the term “marriage rate” is used in the sense of a central rate (i.e., marriages per thousand singles in a given age group), while the term “nuptiality rate” is used for the probability of marriage (Mertens 1965). |

| 5 | However, this is a recent development; in 2001 and 2011, a bachelor was less probable to marry up to 40 years of age than in 1991, but he was more likely to do so at ages after 40 compared to 1991. |

References

- Billari, Francesco C., and Hans-Peter Kohler. 2004. Patterns of Low and Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe. Population Studies 58: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CIA. 2025. Greece. People and Society. The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/greece/#people-and-society (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- ELSTAT. 2024. 2021 Population Census Household Results [Table A05. 2021 Population Census. Resident Population by Sex and Legal Marital Status]. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/2021-census-res-pop-results (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- ELSTAT. n.d. Digital Library: Population Censuses and Statistics of the Natural Movement of the Population of Greece. Available online: http://dlib.statistics.gr/portal/page/portal/ESYE (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- Eurostat. 2025. Life Tables by Age and Sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_mlifetable__custom_15285753/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Gavalas, Vasilis S. 2008. Marriage Patterns in Greece during the Twentieth Century. Continuity and Change 23: 509–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gavalas, Vasilis S. 2015. The World We Have Gained: Population Geography of Modern Greece. Mytilene: Reprographics. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Gavalas, Vasilis S. 2019. The Population of the Aegean Archipelago: 1920–2020 a Century of Demographic and Social Development of the Aegean Societies. Thessaloniki: Disigma. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Gavalas, Vasilis S. 2025. Human Geography of the Ionian Islands. Volos: University of Thessaly Press. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Gavalas, Vasilis S., and Michail Raftakis. 2024. Redefining Family Structures: Births out of Wedlock in 21st Century Greece. Population, Space and Place 30: e2806. [Google Scholar]

- Höpflinger, François. 1985. Changing Marriage Behaviour: Some European Comparisons. Genus 41: 41–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kontogiannis, George. 2022a. The Evolution of Marriages and of Nuptiality in Greece. Demo News 43: 1–4. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Kontogiannis, George. 2022b. Union Formation and Dissolution in the Countries of the European South, with an Emphasis on Greece: A Comparative Analysis. Volos: University of Thessaly. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld, Michaela, Gunnar Andersson, and Ariane Pailhé. 2012. Economic Uncertainty and Family Dynamics in Europe: Introduction. Demographic Research 27: 835–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laslett, Peter. 1983. Family and Household as Work Group and Kin Group: Areas of Traditional Europe Compared. In Family Forms in Historic Europe. Edited by Richard Wall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe, Ron. 2010. The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review 36: 211–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malaker, C. R. 1973. Construction of Nuptiality Tables for the Single Population in India: 1901–1931. Demography 10: 525–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mertens, Walter. 1965. Methodological Aspects of the Construction of Nuptiality Tables. Demography 2: 317–48. [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis, Michael, and Kleon Tsimpos. 2004. Demographic Analysis. Athens: Stamoulis. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Rontos, Kostas, and Luca Salvati. 2020. Space Matters? Exploring Gender Differentials in the Age at Marriage, Greece (1980–2017). Social Sciences 9: 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamaliki, Paraskevi K. 2017. Births, Marriages, and the Economic Environment in Greece: Empirical Evidence over Time. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 38: 218–37. [Google Scholar]

- Saveland, Walt, and Paul Glick. 1969. First-Marriage Decrement Tables by Color and Sex for the United States in 1958–60. Demography 6: 243–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siampos, George. 1993. Demography. Athens: Sbilias. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gavalas, V.S. The Marriage Behavior of the Greek Population from 1991 to 2021: A Study Through Gross Nuptiality Tables. Genealogy 2025, 9, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9020032

Gavalas VS. The Marriage Behavior of the Greek Population from 1991 to 2021: A Study Through Gross Nuptiality Tables. Genealogy. 2025; 9(2):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9020032

Chicago/Turabian StyleGavalas, Vasilis S. 2025. "The Marriage Behavior of the Greek Population from 1991 to 2021: A Study Through Gross Nuptiality Tables" Genealogy 9, no. 2: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9020032

APA StyleGavalas, V. S. (2025). The Marriage Behavior of the Greek Population from 1991 to 2021: A Study Through Gross Nuptiality Tables. Genealogy, 9(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9020032