Abstract

This article examines the type of family lore that leads white Canadians and Americans to claim Indigenous identities. Using a case-study approach, I demonstrate how 2000 descendants of a French-Canadian couple, born in the early 1800s near Montréal, joined one of the largest land claims in Canadian history as “Algonquins”. The tools of critical settler family history provide the necessary theoretical scaffolding to unpack how genealogical and geographical proximity to Indigenous people in the past are the bases for the family lore that propelled these individuals to become card-carrying, voting members of the land claim. Despite continued opposition to their inclusion by the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation, the only federally recognized Algonquin community involved in the land claim, these fake Algonquins remained potential land claim beneficiaries for over two decades, until an independent tribunal finally removed them in 2023. Family lore resolves the crisis in the family: no longer the colonizers responsible for Indigenous displacement and dispossession, white pretendians become the victims of settler colonial violence.

1. Introduction

In this article, I focus on two French-Canadian individuals—Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere, a couple married in 1827 in Saint-Eustache, a small town northwest of Montréal—whose identities were reimagined by white settlers in the Ottawa River Valley sometime in the late 1990s. So successful was their transformation into “Algonquins” that for over two decades, nearly 2000 white settlers with no actual Indigenous ancestry became card-carrying voters and potential beneficiaries in one of the largest land claim negotiations in Canadian history. How did so many white people in this region come to see themselves as Algonquins entitled to lands and monies being negotiated as part of the land claim? And how did these individuals manage to remain members despite repeated attempts by the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation (AOPFN), the only federally recognized Algonquin community involved in the land claim, to remove them between 1999 and 2022?

The entire scheme finally came to an end in 2023, when an independent tribunal found that the couple was indeed French-Canadian, a finding that had the effect of removing their descendants from the land claim. In what follows, I examine the family lore expressed during the tribunal process, when several Lagarde-Carriere descendants submitted detailed briefs outlining what led them to believe that they, and the original couple, were Algonquin. The briefs are public documents that were posted on the Algonquin Tribunal’s website. In each of them, the respondents openly admitted that no documentary evidence existed to support their claims about their Algonquin identities; instead, they mostly rolled out intimate stories that mobilized key tenets of family lore. My analysis focuses specifically on the trope of proximity, in both its genealogical and geographical sense, to tease out the origins of their family lore.

2. Pretendianism, Terror, and Critical Settler Family History

Academic literature on false claims to Indigenous identities has been growing, along with media coverage about prominent cases in the U.S. and Canada. Lenape scholar Joanne Barker’s (2021) most recent book, Red Scare: The State’s Indigenous Terrorist, considers the place of the “Kinless Indian”, or “the Indian without any but an invented relationship to Indigenous people, often cultivated through family or local folklore” (p. 70). Through centring family lore, Barker lays out the usefulness of this figure in upholding settler-colonial logics, since the Kinless Indian is “absolved of responsibility for any benefit from or complicity with state violence against Indigenous people by suggesting that, all along, they were in fact, if in secret, the Indigenous” (p. 71). The Kinless Indian replaces Indigenous peoples, which ultimately “provides a rationale to the state to challenge Indigenous peoples’ rights to sovereignty and self-determination” (p. 71). The Kinless Indian is helpful to the settler state and to society in its efforts to eliminate Indigenous nations and peoples as sovereign entities.

Barker uses the example of Elizabeth Warren’s fanciful claims of Cherokee and Delaware ancestry to illustrate the harm caused by the Kinless Indian. Warren, who self-identified as Native American during her law career, is perhaps the highest-profile Kinless Indian in the U.S. In October 2018, during her campaign to become the Democratic Party’s candidate for president, she posted the results of a DNA ancestry test that she believed confirmed that she had Native American ancestry. President Donald Trump proceeded to give her the nickname “Pocahontas”, relying on abusive generalizations about Indigenous peoples in his critique of Warren. The entire episode was amply treated by Native American (Estes 2018; NoiseCat 2018; Tsosie 2018; Tsosie and Anderson 2018) and particularly Cherokee thinkers (Nagle 2018; Scott 2018) and authorities (Cherokee Nation 2018), who painstakingly called out the harms wrought by Warren’s continued false claims to Indigenous ancestry and identity. Cherokee writer Rebecca Nagle (2019) convincingly demonstrated how the Warren (Crawford) family lore turned living on Native American lands (Creek Nation) to being Native Americans in a way that helped insulate them from accountability for their active participation in colonial violence in the southeastern U.S. and eventually in Oklahoma.

Dakota anthropologist Kim TallBear has become one of the most outspoken scholars on the harms of false claims to Indigenous identities. She has recently argued that what has been alternatively called “self-Indigenization”, “race shifting”, “pretendianism”, or “playing Indian” in the U.S. and Canadian colonial projects has been under-treated as a contemporary form of genocide. “Self-Indigenization”, TallBear (2023) argues, “is a significant contributor in the 21st century to the project of Indigenous elimination and concomitant settler thriving upon the spoils of Indigenous death” (p. 93). As part of her theorization, TallBear has elucidated the specific strategies that “self-Indigenizers” use to create cover for their false claims:

Stealing actual Indigenous people’s stories of trauma and disconnection is a chief strategy that self-Indigenizers use to gain authority. They conflate their exaggerated and fabricated claims with the struggles of actual Indigenous people […] Self-Indigenizers conflate their stories with those of Indigenous people who were kidnapped as children, adopted out to white families, or forced into residential schools and who sometimes did not return to their Indigenous families for decades, if ever. Self-Indigenizers build their authoritative voices by grabbing the mic and speaking from false historical foundations about actual Indigenous people’s lives and what should be done to and about us. (p. 99)

In TallBear’s analysis, self-Indigenizers terrorize Indigenous peoples by replacing them.

In my efforts to explain a phenomenon that has emerged as one of the key weapons in the settler-colonial armoury, I have turned to social and historical studies of family lore—secrets, denials, lies, and other devices that circulate in settler families—to build a conceptual framework that allows me to delve into what is ultimately a complex set of personal and political registers. My first foray into what has become known as “critical family history” was during my undergraduate degree, when I read historian Victoria Freeman’s (2002) Distant Relations: How My Ancestors Colonized North America. I was most struck by how her own family history and genealogy situated Freeman in the thick of settler colonialism. The fact that the earliest English and French settlers in present-day U.S. and Canada have millions upon millions of descendants today means that many other white settlers on these lands share the same history as Freeman and others like us. Freeman’s work demonstrates that tying the experiences of the earliest colonizers to those of their descendants is crucial to understanding current forms of settler colonialism. “Their stories, taken together”, Freeman (2021) argues in a recent reflection on Distant Relations, “illuminated the nitty-gritty processes of colonialism on the ground, confirming that it was not a singular event in the past or the crime of a few immoral or racist leaders, but the result of millions of actions (or non-actions), great and small, by thousands, even millions of people over hundreds of years” (p. 89).

Sociologist Christine Sleeter (2016) has been developing a multidisciplinary understanding of family history in which she also uses her own family’s history to “illustrate the recovery of a silenced or suppressed national narrative [and] show how social relationships that colonization forged, rather than being a relic of the past, live on in the present, and how family history can challenge a national mythology that minimizes the importance and ongoing impact of colonization” (p. 11). By considering her family’s settler history through property records and wills, Sleeter tracks how her ancestors acquired land that had been stolen from Native Americans by various governments. She even discovers that “the memories I grew up with minimized the existence of family wealth, linked what we had with the hard work of my grandparents, and placed our family narrative within the dominant rags-to-riches mythology” (p. 19) that is common in white American families. What appear to be family memories are, in fact, national myths that provide white settler families with routes to escape accountability for racial violence.

Anthropologist Avril Bell’s (2022) work builds on Sleeter’s and and Freeman’s by explicitly theorizing the politics of white settler colonialism in what she calls critical settler family history (CSFH), which:

explores the roles of settler families in (and against) the work of colonialism. Given the centrality of families and home-making to the settler colonial project of taking over the homelands of Indigenous people and creating a ‘new’ society, CSFH is a highly appropriate method for exposing and undercutting the logics and dynamics of colonial violence, wrapped in the seemingly benign practice of settlement. […] CSFH interrogates families’ relationships with Indigenous communities and centres the ways in which the settler family’s home-making is entwined with histories of Indigenous dispossession, and the various forms of violence against Indigenous communities involved in that process. (p. 50)

Besides the focus on the relationships between settler family histories and Indigenous dispossession, another key aspect of Bell’s work is her attention to the forms of forgetting that plague the “histories, literatures, and private family narratives of settler societies” (p. 50). Bell explains that one can counter the work of settler forgetting by focusing on the “gaps, silences, and untruths of family stories” that are passed down from generation to generation (p. 50).

In the study that follows, I use the framework of critical (settler) family history and recent scholarly work on the genocidal impacts of pretendianism to investigate the family histories of a group of white French-Canadians who falsely claim to be Indigenous. I centre their ancestors’ relationships with Indigenous peoples to frame my analysis of their family lore and to demonstrate how forgetting about one’s own ancestors’ involvement in settler colonial violence in the present is a key facet of pretendianism. What Bell calls the “gaps, silences and untruths of family stories” are the interlinked mechanisms behind the creation of family lore.

3. The Algonquin Land Claim in Ontario

3.1. History of the Land Claim and Enrolment Criteria

According to former and current AOPFN Chief Greg Sarazin (1989), the land claim originated in 1974 when Chief Dan Tennisco asked the Union of Ontario Indians’ newly established Rights and Treaty Research Programme (RTRP) to examine a railway right-of-way that the federal government was using on Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation land. The RTRP researcher discovered an 1857 petition that confirmed that the region had never been surrendered by the Algonquins (p. 191).

In 1983, the AOPFN delivered a land claim petition to the Governor-General, signed by almost its entire adult population. The petition was largely based on the language used in 23 previous Algonquin petitions sent to the federal government between 1791 and 1863, in which they requested reserved lands and relief from the violence inflicted by incoming settlers (p. 192). Each of those previous petitions was eventually ignored by the government, which paved the way for the dispossession and displacement of the Algonquin people from parts of their historic territory at the headwaters of the Madawaska, Petawawa, and Rideau rivers in Eastern Ontario.

Like their kin in centuries past, the 1983 petition was at first ignored, with the Ontario government refusing to negotiate with the AOPFN. As a response to the government’s continued inaction, Algonquins set up a roadblock at the main eastern entrance to Algonquin Provincial Park (APP) on 2 September 1988 and asserted their inherent rights by harvesting in the APP, at the heart of their traditional territory (pp. 167–68). As Avery Steed (2020) explains, “between the submission of the 1983 Algonquin petition and the formal acceptance of the land claim for negotiations in the early 1990s—members of the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn began openly asserting their inherent hunting, trapping, and fishing rights in Algonquin Park, deliberately drawing attention to the land claim […] In 1989 alone, 42 charges were laid against seven band members” (p. 18). Once the Government of Ontario formally acknowledged the land claim petition in 1991, they dropped the last of the charges against the Algonquin harvesters.

Algonquin scholar Lynn Gehl (2014) explains that as part of the land claim process initiated by the 1983 petition, the AOPFN developed an Algonquin Enrolment Law (AEL) that followed the recommendations of the government (p. 22). The purpose of the AEL was to identify descendants of historical Algonquins from the territory who had never received Indian status under the Indian Act (1876). The search for these “non-status” (or unrecognized) Algonquins living in Eastern Ontario began as early as 1986, but the process was only formalized in the AEL in the early 1990s (pp. 22–23). The original AEL included a minimum 25% blood quantum clause, which was later changed to 12.5% (or 1/8) to include as many non-status Algonquins as possible. The number of non-status Algonquins who registered with the land claim increased substantially over the first decade, with 300 in 1993, 2000 in 1998, and 4500 by 2000 (p. 24). In 2022, there were over 8000, even though between 1500 and 2000 of those who had previously registered had already been removed in the 2010s.

In 1991, negotiators created non-status Algonquin “area committees” that mostly coincided with the location of historical Algonquin communities to represent the interests of non-status Algonquins who met the AEL criteria. By 1998, seven area committees and the AOPFN formed a new governing entity, the Algonquin Nation Council, under whose purview a constituency list based on the AEL was first created (p. 99). Notably, it was under this new entity that the AOPFN Chief and Council first represented a minority of votes on the land claim’s governing body. In 1999, under this new arrangement, Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere were first included as Algonquin root ancestors as part of the AEL criteria. Within weeks, AOPFN representatives protested the inclusion of Lagarde-Carriere descendants as Algonquins, but their concerns were overruled by the representatives of the area committees.

When a new Chief, Lisa Eshkakogan-Ozawanimke, was elected in 2001, the AOPFN withdrew from the land claim organization and sought to become the sole negotiator. The simmering political conflict erupted in the aftermath of the decision to keep the Lagarde-Carriere descendants in the land claim. During AOPFN’s protest, the non-status area committees added additional entities to its organization, started referring to themselves officially as “First Nations”, and adopted the title “Chief” for its leaders. Further changes approved during the AOPFN’s withdrawal from the negotiation table included a new version of the AEL, developed by the area committees, “which they began to mobilize and rally around. Within this enrollment law, the [area committees] changed the blood quantum requirement to descent only, meaning descent from [an ancestor on] Schedule A was all that was required” (p. 104). When the AOPFN returned to the negotiating table under the banner of the Algonquins of Ontario (AOO) in 2003, lineal descent to an Algonquin ancestor at any generation was now the official criterion used in the land claim. The new enrollment criteria paved the way for the inclusion of a growing number of non-Indigenous and non-Algonquin individuals in the land claim (Leroux 2019, pp. 54–59). All in all, the AOPFN sought out their non-status Algonquin kin in the 1980s and 1990s as part of the land claim negotiations. Over time, representatives of the non-status constituency managed to loosen the membership criteria, to the point that non-Algonquin/non-Indigenous persons were registered in the land claim by the thousands, against the AOPFN’s stated position.

What was a heated conflict between 1999 and 2003 became a full-blown crisis in 2021 and the fate of nearly 2000 Lagarde-Carriere descendants lay in the balance. Before those events, the AOPFN managed to salvage another formal review of the AOO’s membership criteria in 2013.

3.2. Chadwick Decisions, 2013

After years of effort, the AOPFN was able to push the AOO to include a review of the Preliminary List of Algonquin Ancestors (the List) in the draft Agreement-in-Principle. To remove an ancestor, the protestor (or their representative) had to demonstrate (a) that there was some fraud with respect to the original inclusion of an ancestor; (b) that there was new evidence that demonstrated that an ancestor was not Algonquin; or (c) that the original Enrolment Board made a “palpable and overriding error”. In 2013, a retired Superior Court of Ontario judge named James B. Chadwick held hearings in Pembroke to decide whether several ancestors on the List would remain. For an ancestor to be considered for review, either the AOPFN chief, a councillor, or an area committee representative had to file an official protest. The protests were limited to the question of whether an ancestor had been Algonquin. The inclusion of Algonquin ancestors born in the 1600s could not be protested. All six published protests were lodged by one of two AOPFN councillors.

The first hearing, on 7 February, involved root ancestor Simon Gene/Jude Bédard. Chadwick ruled that the ancestor in question was French-Canadian, which removed up to 750 AOO members (Green 2013). The second hearing, on 12 February, involved three related root ancestors—Joseph Fleuri, Julie Fleuri, and Julia Dubé. Chadwick ruled that Joseph and Julie Fleuri must be removed from the List. Furthermore, Chadwick found that the Fleuris were only included because an 1871 Census document was altered to indicate that they were both “Indians”:

As set out in the Enrolment Officer’s June 2012 Report […] the 1871 Census was altered to include the notation that the Fleuri family was ‘Indian’. The original 1871 census does not include reference to the Fleuri family (including Julia Dubé) as being ‘Indian’. […] It is clear that the original Enrolment Board relied on a document that was altered. Since the altered 1871 Census was the only documentary evidence before the Enrolment Board that mentioned the Fleuri family (including Julia Dubé) as being Indian and that census was altered, there is no basis on which the Enrolment Board could have properly found Joseph Fleuri or Julia Dubé to be Algonquin. It would be improper for me to show any deference to a decision that was made on the basis of an altered document. I therefore accept the protest.(Algonquins of Ontario 2013b, pp. 6–7)

Chadwick confirmed that a census document submitted back in 1998 that led to the inclusion of Joseph and Julie Fleuri on the List was altered in such a way as to allow non-Indigenous people to register with the land claim. He avoided assigning blame or responsibility for the fraudulent activity. Chadwick decided to defer a ruling on the continued inclusion of Julia Dubé to consider whether her root ancestor Francoise Grenier (b. 1604) was Algonquin. I demonstrated in my previous work that Grenier was a French woman whose transformation into an “Indigenous” woman had been tied to the self-Indigenization movement in Eastern Canada (Leroux 2019, pp. 82–86). That hearing, which took place on 17 April, featured between five and ten individuals who presented various elements of regional family lore in favour of Grenier’s addition to the List. Among the individuals presenting on behalf of Dubé’s continued inclusion were Connie Mielke, who would later become the area committee representative for Pembroke (“Greater Golden Lake First Nation”), and Larry McDermott, a self-declared Algonquin elder who became the founder and executive director of Plenty Canada, an environmental organization with affiliations to First Nation governance and academic research.

Jim Meness, the protestor, was also in attendance and, according to Chadwick, warned about relying too heavily on family lore: “He pointed out to the numerous supporters of the applicants that the Pikwakanagan First Nations [sic] felt it was their duty and obligation to make sure that anyone who applied for Algonquin heritage was in fact a true Algonquin. […] He also commented on the dangers of relying upon oral history to establish Algonquin heritage. By the application of oral history, everyone is an Indian. He noted that many of the applicants were raised in a French environment, spoke French and of course, the question being are they Algonquin?” (Algonquins of Ontario 2013a, p. 6). Given that a couple of thousand well-known white residents in the Petawawa/Pembroke corridor had managed to become “Algonquin” for the purposes of the land claim, Meness’s statement that “oral history” makes everyone an “Indian” was not simply hyperbole. A historical researcher hired by the AOPFN, Joann McCann, and the AOO’s own enrolment officer, Joan Holmes, presented their respective research into Francoise Grenier’s identity. Both concluded that no evidence existed that Grenier had been Algonquin. Consequently, Chadwick ruled that on a balance of probabilities, Grenier was not Algonquin, which had the effect of removing Julia Dubé from the List (p. 13). In short, the results of these three hearings were the removal of more than 1000 AOO members who had been relying on either Simon Bédard or Joseph/Julie Fleuri and Julia Dubé as root ancestors.

Chadwick’s most difficult task was yet to come, as both Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere’s continued inclusion on the List was put to the test. The stakes were high, as the couple had the largest number of descendants on the List, due in large part to demographic reasons that I outline below. In a hearing that was held on 11 February, Chadwick, relying on the work of AOO enrollment officer Joan Holmes, outlined the history of Thomas Lagarde’s inclusion on the List (Algonquins of Ontario 2013d, p. 3).

Lagarde was first accepted as an Algonquin root ancestor only after the number of registered non-status Algonquins outnumbered the citizens of AOPFN and the area committees outnumbered the AOPFN Chief and Council on the land claim governance body. As such, the federally recognized Algonquins in the region were then a minority in the land claim. In January 2000, Chief Kirby Whiteduck of the AOPFN convinced the Enrolment Board that the census record purporting to identify Thomas Lagarde as “Indian” recorded another individual entirely. At that point, Lagarde was removed as an Algonquin ancestor. Despite his efforts, Chief Whiteduck was unable to permanently remove Lagarde and his descendants from the land claim, because only a few months after they were removed, a Lagarde-Carriere descendant shared two documents that the Enrolment Board accepted as proof that Lagarde had been Algonquin. Somehow, the appellant used the same flawed evidence that was rejected the first time to regain acceptance. The conflict over the inclusion of the Lagarde-Carriere descendants illustrates just how difficult it can be to remove white settlers who have been wrongly recognized as Indigenous by state or pseudo-state apparatuses. It also confirms that the Kinless Indian, in Barker’s (2021) terms, “provides a rationale to the state to challenge Indigenous peoples’ rights to sovereignty and self-determination” (p. 71), since white settler members of the land claim organization had mobilized the AOO to undermine the AOPFN’s sovereign right to determine who is Algonquin.

On 11 February, the Lagarde hearing took place in Pembroke. The two historical researchers at the hearing, one hired by AOPFN and the other working on behalf of the AOO, both presented reports that confirmed that neither Lagarde nor anybody in his family or lineage was ever identified as Indigenous. Nevertheless, one of the area committee representatives, Clifford Bastien, presented a new document that became the lynchpin for Lagarde’s eventual inclusion. The document, a purported letter from a priest named Father Brunet to the Bishop of Montréal in 1845, was translated for the hearing: “I happened upon the little mission at Allumette Island [on the Ottawa River] in the fall of the twenty-second of September [1845]. [I stayed secretly] with a voyageur Tomas Lagarde dit St. Jean, [who is] a member of the Masons and also descended from Algonquins” (Algonquins of Ontario 2013d, p. 7).

Even though the authenticity of the only document that identified Lagarde as an Algonquin was never formally verified, Chadwick decided in favour of retaining Lagarde on the List: “Based upon all the evidence, and in particular the new evidence of correspondence between Father Brunet to the Bishop of Montréal dated 1845, which was not before the original Enrolment Board or before the Review Committee when it ordered a hearing into the facts, I am satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that Thomas Saint Jean dit Lagarde is an Algonquin Ancestor. The protest is therefore rejected” (p. 8).

A similar situation occurred during the hearing into maintaining Lagarde’s wife, Sophie Carriere, on the List (Algonquins of Ontario 2013c). The affected parties presented the retired judge with a baptismal record that indicated that Carriere was Algonquin. The problem with the document was that it misidentified Carriere’s birth mother, who was recorded in several other vital records. In fact, a baptismal certificate already existed for Carriere that did not identify her as Algonquin and correctly identified her birth mother. However, Chadwick may not have been aware of these inconsistencies and decided to retain Carriere on the List. Therefore, after the 2013 hearings, nearly 2000 individuals whose only claim to an Indigenous identity was that Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere were among their ancestors remained registered members of the land claim.

It was only after a CBC investigative journalist published an explosive report on the evidence used to support Lagarde and Carriere’s continued inclusion on the List that the AOO once again opened their (now) Schedule of Algonquin Ancestors to scrutiny. The article, published on 9 August 2021, included interviews with a historian, a handwriting expert, and a forensic document analyst, each of whom concluded that the 1845 Father Brunet correspondence and Carriere’s second birth certificate were most likely forgeries (Leo 2021). The article also outlined how the text from the priest’s letter presented at the 2013 Chadwick hearing could be found in a book called Templar Sanctuaries in North America: Sacred Bloodlines and Secret Treasures. The author of the book, William Mann, is a Lagarde-Carriere descendant and an officer of the Knights Templar of Canada’s Grand Executive Committee and the Sovereign Great Priory’s Grand Archivist. Among the many conspiracy-laden claims contained in the book, Mann argued that the descendants of Jesus and Mary Magdalene live among the Blackfeet people in Montana today. He also argued that the Algonquins, including Thomas Lagarde, were Freemasons who had, for centuries, protected Knights Templar treasures smuggled out of Europe for safekeeping. The article goes on to explain that Mann’s sister was at the 2013 hearing in Pembroke.

All told, the AOPFN leadership had been attempting to oppose the inclusion of white French-Canadians in the land claim negotiations since they were first added back in 1999. They succeeded in removing most of these individuals in 2000 when they demonstrated that a census record used to add a problematic root ancestor was misinterpreted. Despite a lack of reliable evidence, the Enrolment Board overturned this decision less than three months later when the original enrollee appealed. What proceeded was 13 years of land claim negotiations, with up to 3000 persons, at times more than 50% of the AOO members, with no discernable Algonquin or Indigenous ancestry. The 2013 Chadwick decisions removed about 1000 of these individuals, some of whom became leaders of a breakaway group known as the Ardoch Algonquin First Nation. Others became prominent academics at regional universities, promoting their belief that they are the last true Algonquins in the region. The Fleuri/Dubé decision exposed the lengths to which some of these individuals would go to be seen as Algonquin—as Chadwick documented, the inclusion of the Fleuri-Dubé descendants hinged on an altered 1871 Census record.

Unfortunately, Chadwick was unable to detect the forgeries that ensured that Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere remained on the List after 2013. The Knights Templar’s Grand Archivist managed to present documents that were accepted as authentic historical records, even though the AOPFN representative and the AOO’s enrolment officer both demonstrated that Lagarde and Carriere were French-Canadian through verified historical documentation. Once again, we see just how far individuals making false claims to Indigenous identity are willing to go to intervene in formal legal proceedings adjudicating on their identities. On at least three occasions over 15 years (1998–2013), documents that ensured that local white families remained “Algonquin” were altered or forged. Despite these setbacks, the AOPFN was presented with one last chance to oppose the inclusion of white individuals in 2023.

4. Family Lore in the Algonquin Tribunal, 2023

4.1. Lateral Relations and Other Forms of Proximity

After the summer 2021 CBC-Saskatchewan article on Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere, the AOO was in crisis mode. The media coverage had put the integrity of their 2013 adjudication process into considerable question. The news that hundreds of potential beneficiaries with no verifiable Indigenous, let alone Algonquin, ancestry had been registered in the land claim led the AOPFN Chief and Council to remove itself from the negotiations, essentially putting a halt to the process. Remember that the AOPFN had formally opposed the inclusion of Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere on the Schedule of Ancestors on at least three prior occasions by 2021. The CBC articles simply confirmed what many AOPFN citizens already knew to be true—the Turcottes, Clouthiers, Paquettes, and Chartrands, all well-known regional families descended from the Lagarde-Carriere union, were not and had never been Algonquin.

The following analysis considers the tribunal submissions made by eight AOO members who were eventually removed from the organization’s membership because they had no Indigenous ancestry. Each of them relied only on a genealogical connection to Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere for their membership. Their submissions to the Tribunal were their final opportunities to make the case that Lagarde and Carriere should remain on the List. Since no verified documentation existed to support their claims, they relied heavily on family lore.

The first submission was made by Lynn Clouthier, who had been the Algonquin Nation Representative for the urban community of Ottawa for over a decade. As such, she had a vote on the main AOO decision-making body. Her submission included stories and reports by five other AOO members: Emmett Godin, Ronald Romain Sr., Jane Lagassie, Carole Turcotte, and Geoff Souliere. The second submission was made by Connie Mielke and Denise Chaput. Mielke had been the Algonquin Nation Representative for the Greater Golden Lake (Pembroke) community, even embracing the title of “Chief”, for nearly a decade.

One notable aspect of the arguments forwarded by their submissions was the effort to demonstrate genealogical connections between their French-Canadian ancestors and Algonquins. This form of proximity is a central trope of family lore about Indigenous identity. Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere were a French-Canadian couple from a French-Canadian parish town northwest of Montréal. Nothing in the historical record suggests otherwise. However, the Clouthier and the Mielke and Chaput submissions are replete with the types of stories of genealogical proximity that have become common in pretendian family lore. As Barker (2021) has argued, the Kinless Indian uses family lore because they only have an invented familial relationship with Indigenous people (p. 70).

In their introduction, Chaput and Mielke (2023a) provide a clear account of their effort to create a relationship with Algonquin people: “Our lineage intertwines with many Algonquin lines through marriage and being raised with them. This we wish to show you, because we believe that this shows many from our line who grew up believing they were Algonquin and still believe that to this day” (p. 1). They proceed to point out several lateral relations and genealogical connections that may confuse outside parties but simply do not confirm their Algonquin identities.

For example, in Document D of Clouthier’s (2023) submission, Carole Turcotte traces the ancestry of Francois-Xavier Turcotte’s younger brother, Nazaire. Francois-Xavier married Sophie St. Jean, Thomas Lagarde’s daughter. His brother Nazaire married Marie-Anne Lemaire, whose mother was an Anishinabek woman named Marie-Anne Wendapikinum. While this genealogical connection to an Indigenous woman is factual, Nazaire is Thomas Lagarde’s son-in-law’s brother; therefore, whom he married is unrelated to Lagarde or Carriere’s identities. Put another way, for the average Lagarde-Carriere descendant born in the 1950s to 1970s, Wendapikinum is their great-great-great-grandparents’ son-in-law’s brother’s wife’s mother. Individuals making false claims to an Indigenous identity understand the importance of establishing some form of kinship relation to legitimize their assertion, but they wrongly believe that a trace of “Indian blood” is a marker of identity, eliding the significance of the practice of kinship and its obligations (Pierce 2017).

TallBear (2023) explains how self-Indigenization relies on Indigenous bio-matter in the form of “blood” to further genocidal strategies: “Self-Indigenization is an ultimate act of colonial appropriation, whether self-Indigenizers intend it or not. Self-Indigenization co-evolves with recognized genocidal strategies. It is predicated on 200 years of racial science across disciplines co-constituted with settler state laws and policies designed to kill the Indian within the human. Individuals may survive, but actual Indigenous collectives must remain conquered, controlled, and sufficiently alive only to provide the bio- or cultural matter necessary for the vampiric thriving of a settler state” (p. 100). The Tribunal submissions illustrate the vampiric tendency to steal away Indigenous blood.

A second document in Lynn Clouthier’s submission relies on similar distant lateral relations to assert that Sophie Carriere was Algonquin. In the unsigned document titled “French-Algonquin Family Alliances”, we are told that Carriere’s paternal grandmother Marie-Madeleine Marier’s uncle Antoine Marier married Marguerite Louise Duboc, whose grandmother was a Huron-Wendat woman named Marie Felix Ouentonouen Arontio (b. 1640). In this case, the author is claiming a proximate relation to their great-great-great-great-great-grandmother’s uncle’s wife’s grandmother. None of these are direct ancestors, and even if they were, Arontio’s descendants lived as white French-Canadians for generations. Counting her among a couple of thousand of one’s root ancestors at that generational depth does not make one Indigenous today. In fact, TallBear (2023) calls efforts such as these to reclaim a generations-old ancestor the “needle in a haystack” (p. 99) of self-Indigenization, to make a point about their arcane nature. Nonetheless, part of the family lore mobilized in the Tribunal process seeks to identify potential “Indigenous” ancestors, no matter how distant or speculative, in the hopes that their descendants will remain AOO members.

The author also does not answer an obvious question: how would having a Huron-Wendat ancestor make one Algonquin today? One does not become Algonquin based on a “pan-Indigenous” ancestor, as Trevino L. Brings Plenty (2018) explains: “The Pretend Indian is an alt-reality. Their operating system is calibrated through a magical pan-Indianism experience. A Pretend Pan-Indian” (p. 146). Francoise Grenier (a French woman born circa 1604) and Marie Felix Ouentonouen Arontio (a Huron-Wendat woman born circa 1641) are used as “pretend pan-Indians” by Turcotte and other AOO members with no known Indigenous ancestry to transform themselves into Algonquins.

In their own submission, Chaput and Mielke also rely extensively on the trope of proximity through lateral relations. For instance, they give the example of Thomas Lagarde’s great-great grandson, Norman Sylvestre (a first cousin of and godfather to one of the authors), who married Joyce Elizabeth Needham, Algonquin woman Mary-Ann Jocko’s granddaughter. In this case, instead of looking back to find proximate relations for Lagarde, they look forward to his descendants. However, just because Thomas Lagarde’s great-great-grandchild married an Indigenous person, this does not transform Lagarde into an Indigenous ancestor. Chaput and Mielke would have us believe that all Lagarde and Carriere’s descendants are Algonquin because a few descendants married Algonquin people: “Our lineage intertwines with many Algonquin lines through marriage and being raised with them.” The slippage between their and our in their introductory statement is subtle and masks the fact that their own lineage does not intertwine with Algonquins at all. Their claim does not involve a trace of blood but builds proximity with extended family members who have been touched with this trace. What is left from their introductory statement is the fact that they were “raised” with Algonquins, a fact that may be true but does not confer an Indigenous identity on hundreds of white people in the region.

Since the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation is surrounded by much larger settler towns, it follows that generations of white settlers in the Ottawa River valley grew up knowing Algonquin peers. What is missing from these statements of affinity with the Algonquin people is the well-documented animosity that white settlers from towns such as Petawawa, Pembroke, and Renfrew have shown to Algonquins. One high-profile example is that of the former Member of Parliament (MP) for Renfrew-Nipissing-Pembroke, Hector Clouthier. A Lagarde-Carriere descendant, prior to becoming a politician, Clouthier was an executive of a family-owned lumber company in Pembroke founded by his father. As such, he was well-known in the region. At the start of his political career in 1992, Clouthier made repeated public comments disparaging Indigenous peoples. His racist views were so toxic that the Liberal Party barred him from running for public office under its banner for the next five years (Miljan 2000). Clouthier was eventually elected in 1997 as a Liberal and held a minor Cabinet position. Sometime afterwards, he and his children enrolled in the AOO. They were removed in 2023, along with the other AOO members relying solely on Lagarde and Carriere as root “Algonquin” ancestors. While Chaput and Mielke present a picture in which the Turcotte and affiliated families are Algonquin by virtue of their closeness with Algonquins (“being raised with them”), they omit the fact that these same families often fomented anti-Indigenous racism in the region. Barker (2021) usefully argues that the Kinless Indian absolves itself of responsibility for any benefit from state violence against Indigenous peoples, and, I would add, everyday forms of racism “by suggesting that, all along, they were in fact, if in secret, the Indigenous” (p. 71). Understandably, having a former public official renowned for his anti-Indigenous racism registered with the AOO further confirmed the AOPFN’s belief that non-Algonquins had infiltrated the land claim process.

Table 1, below, documents the types of lateral genealogical relations that are used in the Algonquin Tribunal submissions. The first column documents the lateral ancestor whose identity is being used by the authors, while the second column documents the direct ancestor who is related to the Lagarde-Carriere couple. The final column documents the degree of relationship of the lateral ancestors identified in column one with a typical living descendant of Lagarde-Carriere born in the 1950s to 1970s.

Table 1.

Lateral genealogical ancestors (by year of birth).

The authors’ ardent attempts to suggest that Lagarde and Carriere were Algonquin might confuse or distract readers who are unfamiliar with the names, dates, and locations they persistently repeat, but, ultimately, their heavy reliance on lateral relations and long-ago genealogical ties betrays the weakness of their claim to an Algonquin identity. It also exposes the likely basis for their belief that Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere were Algonquin—that a few of the thousands of their descendants in the Ottawa River Valley married local Algonquin people in the past 150 years. While that observation may be unsurprising, it appears that many Lagarde-Carriere descendants reimagine themselves as Algonquin partly due to these intermarriages.

The next section turns to another, complementary understanding of proximity in my analysis. Not simply relying on proximity to a trace of blood, individuals making false claims to Indigenous identity rely heavily on geographical proximity in their retelling of family history.

4.2. Algonquin Dispossession, Settler Proximity

The trope of proximity often equivocates between the genealogical and the geographical. The expression of family lore sometimes displaces the geographical in favour of the genealogical, to prioritise blood over all else. When it comes to proximity, however, a white settler family’s geographic closeness to Indigenous people, especially to Indigenous communities in the past, can be key to mobilizing their faith in their ancestor’s indigeneity. That their ancestors’ presence may have been part of the process that violently displaced these same Indigenous communities evades their historical consciousness. Sleeter argues that we can challenge white families’ desire for innocence by “identifying the location of our families within the racial or colonial structure [and] ask how that location shaped possibilities open to them” (p. 14). I want to take Sleeter’s work in a new direction, one that teases out its geographical imagination. When she refers to the location of our families within the racial/colonial structure, we might interpret that to mean a family’s place in hierarchical relations, over and above Indigenous peoples, for instance. But my findings suggest that there is another, equally significant way to envision location in family lore that involves false claims to an Indigenous identity—as closeness or adjacency. What I am suggesting is that we interpret location to mean a place that existed and does exist, often next to a historical Indigenous community (and, less often, next to a current one). Simply put, place-ing our family in the past is an essential component of understanding what possibilities were open to our ancestors as colonizers, including to reimagine themselves as Indigenous.

Algonquin territory, or the Ottawa River watershed, has become a place that invites white Canadians to transform their identities based on family lore. It shapes the possibilities open to them as white settlers. Quite often, living close to Algonquin people turns into being Algonquin. It is not just a matter of certain members of these families making outlandish claims. Ashley Barnwell (2018, 2019), Tanya Evans (2011), and Sleeter (2016) have all argued convincingly that family stories are intimately bound up with national stories or mythology. For generations, the Algonquin presence in the region had been effectively erased by Canadian efforts to justify its theft of the heart of Algonquin territory, including the present-day location of Canada’s Parliament Buildings (also known as Parliament Hill). The Algonquin writer Kermot Moore (1982) details how Michel Shene’s family from Hunter’s Point (Wolf Lake First Nation) were dispossessed from their lands in the mid-1800s:

As he explained to his people, he himself had been told that the site of the Government of Canada was close to where the Rideau River flows into the Ottawa [River]. This had been the site of one of his family’s camps when he was a boy. His family had been forced to leave the Rideau River when men bearing pieces of paper called ‘titles’ confronted them with orders that they would have to move. Explaining that these titles were very powerful pieces of paper because they carried the government’s word, they added that the government had given their land to other people who were going to use it for better purposes. The Shenes were told that they should move upstream. […] Shene’s family moved several times, each time finding that they had encroached on another [white] family’s territory. (p. 65)

Moore explains that Shene and two other Algonquin Elders, Joe Petremont and Jim Stanger, visited Ottawa in 1920 to make a claim to lands that had been stolen by the government and to protect their lands south of Lake Temiskaming. They showed up on Parliament Hill and were “shunted over to the Department of Indian Affairs, where they faced ridicule from its bureaucrats” (p. 66). Shene informed the bureaucrats that the Parliament Buildings were located on his family’s hunting grounds, which the officials claimed was preposterous. The three men ultimately returned home with the knowledge that the Government of Canada was hostile to their interests (p. 66). These types of experiences of erasure, qua elimination, were common to Algonquin people throughout the region, which is now the seat of government power and authority across millions of square kilometres of Indigenous lands. It is no coincidence that Ottawa and its environs have become the geographical locus of the race-shifting movement—it is as if white settlers seek to justify the government’s authority and power over Indigenous peoples by becoming Indigenous themselves. The region is home to no fewer than 19 organizations that grant membership only or in part to non-Indigenous people, which are spread out across more than a dozen towns and cities in Quebec and Ontario and have registered at least 25,000 local people. Appendix A features information about these organizations.

In addition to the glut of organizations in the region representing self-identified “Indigenous” people, either as “non-status Algonquins” or “Métis,” there have been 17 court cases involving individuals belonging to one of the organizations in Appendix A. Eleven of the seventeen court cases involved individuals who faced charges related to illegal hunting and fishing or breaching other wildlife, environmental, or public land regulations. In each of these court cases between 2011 and 2023, the defendants claimed they had access to Aboriginal rights as Indigenous people (usually as Métis), under section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982). In every case, they lost. Three other court cases involved an organization seeking an exemption from the payment of municipal property taxes due to its representing “Indigenous” members. Two out of three property tax decisions were in their favour, illustrating the confusion about their claims that still reigns in the courtroom. Finally, three cases involved members of the Painted Feather Woodland Métis, two in Ontario and one in British Columbia. In each of these cases, the individual was convicted of a criminal offence and was requesting post-conviction relief during sentencing that is at times available to Indigenous people. In these cases, the judge rejected their request, primarily on the grounds that the individual did not provide sufficient evidence of their Indigenous identity. Appendix B summarizes my findings about these court cases.

A key discovery related to the court cases revolves around the genealogical bases for regional claims to an Indigenous identity. The 14 court decisions involving individual defendants identify the ancestry of 22 people. Of these, all were members of an organization operating in Algonquin territory at the time of the judge’s decision. Nine of the twenty-two individuals or 40.9% have no Indigenous ancestry whatsoever because they rely on a French woman such as Francoise Grenier as their “Indigenous” root ancestor for membership in one of either the Painted Feather Woodland Metis, the Maniwaki Metis Community, or the Native Alliance of Quebec. Of the remaining 13 individuals, the average ancestral depth of their Indigenous “root ancestor” is 8.2 generations or an ancestor born in the first decades of the 1700s. The “needle in the haystack” or the “trace of blood” appears not only in family lore but also in the organizational infrastructure that empowers individuals to test their new identities in court.

The next section builds on the preceding analysis of geographical proximity by examining the claims for the existence of a historical Algonquin community on the Petawawa River at Black Bay, about 30 kilometres northwest of Pembroke. The claims about Black Bay were common in Tribunal submissions. Turning a historical French-Canadian settlement into an Algonquin one is a useful strategy that transforms geographical closeness into sameness.

4.3. The Turcotte “Clan”, Black Bay, and Algonquin Provincial Park

Family lore often turns a white settlement into an “Indigenous” one, as is the case with the hamlet of Black Bay at the junction of the Petawawa and Barron rivers, a few kilometres upstream from the Ottawa River. The Bay is separated from the main stem of the river by an approximately three-kilometre peninsula that encompasses the hamlet. According to Chaput and Mielke’s (2023b) third submission, 9 of the 11 original land patents on the peninsula were granted to five French-Canadian families (Turcotte, Chartrand, Sylvestre, Paquette, and Charette). These families were surrounded primarily by German settlers, with a smaller number of Anglo- and Irish settlers also scattered about. From available census records and submissions to the Tribunal, it appears that these families settled in Black Bay in the 1870s in the years immediately after the Government of Ontario passed the Free Grants and Homestead Act (1868), which offered white settler men who were 18 years or older 100 acres of land (up to 200 acres if the land was difficult to farm). A settler man could procure a patent (deed) within five years, if he built a cabin at least 20 feet by 16 feet, cleared at least two acres a year, and stayed there (with his family) during that time. The new law paved the way for the Government of Ontario to allot unceded Algonquin lands to white settlers at a time when they were refusing to grant land to Algonquins.

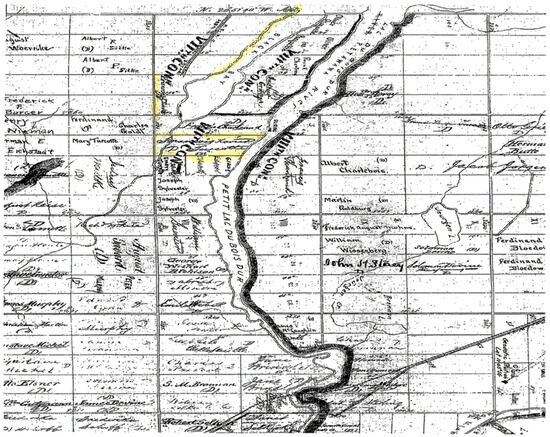

The map provided by Chaput and Mielke (Figure 1) appears to represent land ownership in Black Bay and its environs around 1880, confirming that several prominent French-Canadian families in the hamlet owned a considerable amount of property.

Figure 1.

Original land patents at Black Bay.

The origins of the family lore about Black Bay appear to be partly connected to the fact that several of these families lived and/or made a living hunting and trapping in land upstream from Black Bay along the Barron River that would later become part of Algonquin Provincial Park. Carole Turcotte, writing in Lynn Clouthier’s (2023) submission, shares the lore:

A current elder from the Turcotte clan identified Black Bay and Algonquin Park as special areas in which his extended family members and related Algonquins [sic] congregated to camp, hunt, fish, and socialize. He states that two of his aunts were born inside Algonquin Park at No. 1 Lake. After the park was established in the 1890s, family history was confirmed by another of the Godin brothers. Other family members identified Black Bay, Allumette Island, and Cedar Beach Campsite at Algonquin Park, as places that are significant areas where they live, camp, hunt, pick berries, and have family gatherings. One descendant of the Turcotte family explained how they were removed from the park. His aunts had been born at Lake No. 1. After living there for 150 years, my ancestors were removed and settled in the Black Bay area. My aunt moved in with her son, the Ministry [of Lands and Forests] I suppose burnt the homestead, I believe to accommodate hydro [production]. (p. 5)

Without a doubt, the creation of Algonquin Provincial Park (APP) dispossessed and displaced Algonquin people who had been living and/or harvesting and practicing ceremonies within its eventual boundaries since time immemorial. A petition dated 21 July 1863 and titled “Petition from the Indians of the Village of Two Mountains hunting on the headwaters of the Madawaska and other rivers of central Canada” featured the signatures of 250 Algonquins. Addressed to Governor-General Charles Viscount Monk, it starkly outlines the Algonquin people’s efforts at survival in the face of intensifying colonial settler encroachment:

The humble petitions of the undersigned Indians of the Village of Two Mountains, hunting on the headwaters of the Madawaska and other rivers of central Canada,Respectfully sheweth,1. That in times past the hunting grounds of your Petitioners were in the country watered by the Madawaska and adjoining streams […] but owing to that country having become during the past few years thickly settled it has been rendered useless and destroyed their hunting grounds, and has compelled your Petitioners in order to obtain food and clothing for themselves and their families to travel still further westward […].2. That owing to […] the extreme poverty of your humble Indian Petitioners, it nearly takes all that they receive in money, trade or exchange for the spoils of their hunt to meet, after returning to their homes, the debts they have contracted between their hunting seasons.3. That your Petitioners as a race are fast fading away before the influence of their brethren the White Men, whose gradual but constant encroachments have already nearly exterminated them and the few that remain are reduced in poverty to almost absolute want and their old hunting grounds having been taken possession of and rendered useless there appears no prospect before them but that of starvation, misery and death unless the Good Spirit influence the hearts of their Fathers the Governor and his Council to help them.4. That your petitioners are desirous of having a tract of land near their present hunting grounds granted or reserved to them for the purpose of building up an Indian village capable of supporting about Four Hundred Families, a desire which they sincerely trust will be gratified by their Father in His Council when he considers that the whole country was once theirs and the land of the departed braves, their fathers.5. That such a tract of land as would suit the purposes required, your Petitioners have found […] four thousand acres of which, or thereabouts, taken off that portion of the Township of Lawrence […] is near their hunting grounds, is suitable for their village, and would be the greatest blessing that could be bestowed upon your Petitioners and the whole Algonquin Tribe […]Therefore your Petitioners humbly pray that Your Excellency in pity to the Indian race, as an act of charity to them in their extreme poverty, and as an act of justice to them in consideration of their former rights, will be graciously pleased to make an Order in your Council granting to them Four Thousand acres of land in the Township of Lawrence […] to be reserved to them for the purposes of an Indian Village, and will be further pleased to make such further orders and do such further acts as in pity to our scattered tribes and families.Your Excellency may think best for us as Faithful Indian Children.(Cited in Holmes 1993, pp. 151–52)

The Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands advised the petitioners that the requested land—near the headwaters of both the Madawaska and Petawawa rivers—was being set aside for Algonquin settlement, but after several decades of communication between Algonquin leadership and Crown authorities, the province added the Township of Lawrence to Algonquin Provincial Park in 1911, blocking Algonquin access to their lands. You may remember that in the late 1980s, Algonquins from the AOPFN asserted their rights to hunt and fish in APP, eventually having those rights affirmed by government. Before those victories, Algonquin people had been banned from harvesting in APP for nearly a century.

In the case of the Turcotte “clan”, we have a markedly different situation, one in which the settler-ancestors who participated in the dispossession of the regional Algonquin population are reimagined as Algonquins. The provincial park boundaries are about 15 kilometres west of Black Bay, and Number One Lake, mentioned twice in Turcotte’s statement, is the closest lake within the provincial park to the hamlet. In this case, because French-Canadian families whose homesteads were at Black Bay used parts of the region that would be annexed to APP, Turcotte suggests that they experienced the same land theft and racial violence as Algonquins. As TallBear (2023) argues, “stealing actual Indigenous people’s stories of trauma and disconnection is a chief strategy that self-Indigenizers use to gain authority. They conflate their exaggerated and fabricated claims with the struggles of actual Indigenous people” (p. 99). Turcotte and Chaput and Mielke steal the pain and suffering experienced by the Algonquin people in the 19th century, as captured in the 1863 petition, to legitimize their false claims. Their ancestors did not live in the provincial park for 150 years, as Turcotte dramatically insists. Instead, they all arrived in the region in the 1860s and 70s, about 40 years prior to the creation of the provincial park, to claim lands stolen from the Algonquin people.

To understand the precise origins and circulation of family lore about the Turcotte family, we must examine historical records from the period, following Bell’s critical settler family history approach. François-Xavier (F-X) Turcotte, the root ancestor for the regional Turcotte family, was born in 1820 in L’Assomption, a rural parish about 40 km northeast of Montréal. He married Sophie St. Jean, Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere’s daughter, near Pembroke in 1849. Figure 2, an undated photo of the couple, with a daughter and two grandchildren, was shared repeatedly in submissions to the Tribunal.

Figure 2.

Sophie St. Jean, sitting on the left, and François-Xavier Turcotte, sitting on the right.

Turcotte had nine documented siblings (he was the third oldest), all of whom married fellow white settlers. According to censuses and vital records, none of his siblings or their children lived in Algonquin territory. Thus, the Turcotte clan, as presented in the tribunal submissions, comprises F-X Turcotte and Sophie St. Jean’s descendants, as well as his descendants with his second wife, Victoria Perrin. Together, they had 19 children. The Original Land Patents map provided by Chaput and Mielke (Figure 1) is highlighted to mark Turcotte’s large double lot fronting the Petawawa River at the bottom of Black Bay.

Turcotte was first enumerated along with his family as living in Black Bay in the 1871 Census. Prior to that, they lived across the Ottawa River near Waltham, QC, where most of his children with Sophie Lagarde St. Jean were born. The family moved to the Petawawa area sometime in the late 1860s, after the township was formally created in 1865. Most of his children were documented as living in Black Bay between the 1871 and 1921 censuses. The timeline I uncovered for the family’s presence at Black Bay contradicts Carole Turcotte’s previous claim that the Turcotte family had lived in what became Algonquin Provincial Park for 150 years. Chaput and Mielke (2023b) repeated the same claim in their own submission, which suggests that Turcotte family lore has consolidated around the idea that the family was forcefully displaced by the creation of APP. However, as I demonstrate, the root ancestors of the Turcotte clan all arrived directly from different parts of Quebec only a few decades before the creation of APP and lived at Black Bay, not in the park.

Not only does the Turcotte family stay close to their land patents at Black Bay, but they intermarry extensively with other land-owning French-Canadian families in the hamlet. Sophie Turcotte (1850–1892) married Luc Clouthier, who moved to the Petawawa area from an area downstream of Gatineau in Quebec. He was enumerated in the 1871 Census in a rural municipality north of Petawawa, where he lived with his brother, who owned an inn near the Ottawa River. Elizabeth Turcotte (1861–1935) married Michel Chartrand, whose father François-Xavier was the first Chartrand to settle in the area. The elder Chartrand was from Laval, north of Montréal, and was first recorded in Petawawa in the 1871 Census. Figure 1 indicates that Michel’s father owned two lots at Black Bay, including one directly north of the Turcotte lots and one directly south of Oliver Paquette’s lots at the top of the peninsula. Paquette was from Mirabel, another town north of Montréal, and was also first recorded in Petawawa in the 1871 Census. He was married to his neighbour Michel Chartrand’s sister, Olive. Julie-Anne Turcotte (1862–1914), Elizabeth and Sophie’s younger sister, married Oliver Paquette’s son, Oliver Jr., ensuring that the Turcotte, Chartrand, Clouthier, and Paquette families were deeply intertwined. Bruno Turcotte (1867–1952) even married his niece, Melina Turcotte; they were enumerated in the 1911 and 1921 censuses as living on the Turcotte lots at Black Bay.

My research uncovered the fact that the Turcotte, Clouthier, Chartrand, and Paquette families settled in Black Bay immediately after the passing of the Free Grants and Homestead Act, through which each head of household obtained “free” land at a time and in a place where Algonquin people were being forcefully evicted from their lands. Algonquins, as Indigenous people, were not eligible for the free land offered under the 1868 legislation.

Intermarriage between the four root-ancestor families and other local French-Canadian families such as Emond, Chaput, Brunet, Traversy, and Sylvestre continued well into the first decades of the twentieth century. The use of the term “clan” to refer to the descendants of the original Turcotte–Lagarde union speaks to their apparent commitment to intermarry and live on their land patents on (or near) the Black Bay Peninsula. According to the Assessment Roll for the Township of Petawawa, which is a public record of taxable property, the Turcotte clan owned 790 acres of land at Black Bay, spread across six heads of household, in 1882 (Petawawa Public Library 2024). The 1911 Assessment Roll indicates that 20 heads of household in the clan owned 1719 acres of land at Black Bay, an acreage that had nearly doubled over the course of about a generation.

I was also able to document 33 marriages between members of the so-called Turcotte clan from circa 1885 to 1930. Among those marriages, six were between first cousins, five were between second cousins, and three were between an uncle or aunt and their niece or nephew. One of the main advantages of this type of intermarriage was that any land granted to the family by the Government of Ontario in the 1870s and 1880s remained in the Turcotte clan’s hands. The subdivision of property ensured that the family was able to accumulate wealth over generations. For example, while the amount of acreage owned by the Turcotte clan increased by 117.6% between 1882 and 1911, the amount of assessed value owned by the clan increased by 228.3% because they were able to leverage their land to construct houses, sawmills, barns, sheds, and other outbuildings. Overall, their extensive land holdings laid the groundwork for the mostly middle-class experience of their living descendants. Of course, another possible outcome of consistent intermarriage among family members—including marriages between cousins and uncles/aunts and their nieces/nephews—was to experience social stigma and shame that could lead to the creation of family lore in the first place, as sociologists Carole Smart (2011) and Ashley Barnwell (2018, 2019) have demonstrated.

My findings confirm that the Turcotte clan, as it was called in Lynn Clouthier’s (2023) submission to the Algonquin Tribunal, was created through repeated intermarriage among several families that had been granted “free land” by the Government of Ontario at Black Bay outside of the town of Petawawa. The government’s land incentive attracted tens of thousands of Québécois residents to Algonquin/Anishinaabeg territory, including my own paternal and maternal great-great-grandparents, who accessed land in the 1880s in Robinson–Huron treaty territory along the railway in Verner (near North Bay) and in Hanmer (outside Sudbury). Like my own family, their move, and that of other affiliated families, coincided with the new law in Ontario that granted stolen Algonquin lands to white settlers.

Not surprisingly, as happened among the first settler families in the Petawawa region, some Turcotte family members married Algonquin persons. For instance, Joseph Montreuil (1846–1940), the Algonquin woman Marie Kakwabit’s son, married Lavinia Chartrand in 1883. The couple lived for a few years in Pembroke before moving about 200 kilometres away, near North Bay. Theophile Montreuil, another of Kakwabit’s sons, married Josephine Chartrand in 1880. In the 1881 Census of Black Bay, the couple was enumerated in Josephine’s parents’ household in Black Bay. By the 1901 Census, Josephine was a widow, living with her mother (also a widow) and her seven children. Three of the Montreuil-Chartrand daughters, who were raised primarily by their French-Canadian mother and grandmother after their father’s untimely death, married into the extended Turcotte family at Black Bay, including Delia (with her first cousin, Alexander Emond), Anastasie Marie (with John Clouthier), and Josephine (with Luc Pierre Clouthier). Overall, two of Marie Kakwabit’s children and three of her grandchildren married into the Turcotte family, with four of these couples living primarily at Black Bay. These unions represent most of the genealogical connections evoked in the Clouthier and Chaput and Mielke submissions to the Algonquin Tribunal, despite their representing far less than 10% of all unions at that generational depth. Importantly, all of Marie Kakwabit’s descendants are considered non-status Algonquins by the land claim governing body.

The Turcotte clan lived near each other at Black Bay for around two to three generations. During this period, they also lived among one branch of Montreuil descendants, who all counted Marie Kakwabit as their mother or grandmother. While Marie herself did not live at Black Bay, the presence of her child Theophile and his seven children there, and the fact that three of his children married Turcotte family members, appears to be partly the basis of the collective belief that Black Bay was a historical Algonquin community. No other evidence for this claim was presented at the Algonquin Tribunal, even though the belief was repeated by several different Turcotte “clan” members.

My analysis demonstrates that geographical and genealogical proximity are intertwined tropes at the basis of regional family lore. Understanding false claims to Indigenous identity requires us to unpack historical knowledge about local families within the matrix of broader settler-colonial politics.

5. Conclusions

In this article, I consider the creation and circulation of the family lore linked to about 2000 white individuals in eastern Ontario who joined a high-profile land claim negotiation in the 2000s. All these individuals were eventually removed from the land claim in 2023 because their “Algonquin” root ancestors turned out to be a well-documented French-Canadian couple. Despite the existence of professional research supporting their removal since at least 2013 and the active opposition of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation (AOPFN) since 1999, several of the individuals shared their family lore during an independent tribunal set up to adjudicate on the inclusion of certain ancestors on the Algonquins of Ontario’s Schedule of Algonquin Ancestors.

Just as the AOPFN consistently undertook to remove these individuals from the land claim, Lagarde-Carriere descendants sought to remain with equal vigour. My research publicly exposes for the first time that an 1871 census record was altered to indicate that a root ancestor was “Indian.” The fraud was only discovered during a 2013 hearing, meaning that hundreds of white members other than the Lagarde-Carriere descendants were part of the land claim for about 15 years. Notably, the 1998 alteration of a historical document was not the only occasion during which pretendians used subterfuge to secure their recognition. In the 2013 hearings, two forged documents were used to secure the continued inclusion of Thomas Lagarde and Sophie Carriere on the Schedule. Remarkably, the documents were created by a noted conspiracy theorist who was also a Lagarde-Carriere descendant and AOO member. Thanks to these forged documents, about 2000 individuals remained potential beneficiaries of the land claim and were able to vote on the Agreement-in-Principle in 2016.

These three cases of altered and/or forged documents point to a key takeaway: once white individuals are formally recognized as “Indigenous”, it is exceedingly difficult to revoke this status. The AOPFN actively tried to remove the descendants of this one French-Canadian couple from the land claim on every available occasion, but it took more than 20 years to convince the formal governance structure to do so. During that time, the number of individuals wrongly registered as Algonquin, based on an ancestral relationship with this couple, skyrocketed from a handful of people to about 2000. Media coverage of the affair finally prompted the organization to set up an independent tribunal that found in favour of the AOPFN. During the intervening 24 years, numerous white individuals became “chiefs”, staff, and public representatives of the land claim. One such individual even became president of the real estate arm of the Algonquins of Ontario and was responsible for a controversial municipal land deal in Ottawa worth hundreds of millions of dollars (Porter 2021). Others became university professors, public servants, and leaders of Indigenous initiatives throughout the country, propelled by their false claim to an Algonquin identity. The confusion and disarray created by the AOO’s membership failures continue to reverberate in the region, as Ottawa-Gatineau has become a hotbed for pretendianism nationally. The number of organizations representing individuals making false claims to either an Algonquin or Métis identity within a two- to three-hour drive of the city is unmatched elsewhere.

Overall, this article demonstrates the extent to which family lore can seep into the lives of extended family members who may not even know each other. The transformation of Black Bay into an Algonquin community circulated far and wide through the Ottawa Valley, becoming a justification for white people’s registration in the land claim. Effectively intervening in false claims to Indigenous identities, particularly those made on a collective level as presented in this article, requires robust knowledge about local histories. It also requires active solidarity with First Nation people who, for too long, have had their concerns about the harms of pretendianism ignored by well-meaning scholars and public institutions that are too ready to side with those making false claims. Similar to the Chumash people in Haley’s article in this Special Issue, Algonquin people have been sounding the alarm bells about the thousands of Lagarde-Carrière, Bédard, and Fleuri descendants who contrived a route to recognition for decades, only to see many of these individuals accessing the right to hunt moose in Algonquin Provincial Park, collect education/arts funding, and obtain employment reserved for Algonquin or Indigenous applicants. Tens of millions of dollars in funding and salaries have been paid out to fake Algonquins, often in the name of reconciliation. Besides the material cost of these lost opportunities, Algonquin pretendians in government, academia, and the arts have often been the sole representative voice of Algonquins/Indigenous people at their institution, ensuring that Algonquins/Indigenous people have been shut out from decisions impacting their lives.

Respecting Indigenous sovereignty means working with local Indigenous governing bodies to put an end to Indigenous identity fraud in our research projects, at our institutions, and in our lives.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#430-2020-00715).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data is included in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Organizations in Algonquin territory (alphabetical).

Table A1.

Organizations in Algonquin territory (alphabetical).

| Organization | Location | Origins | # of Members |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Algonquins of Ontario | Pembroke, ON | 2004 | At least 3000 white members between 1999 and 2023. |

| 2. Ardoch Algonquin First Nation | Ardoch, ON | 1980s | |

| 3. Confederation of Aboriginal Peoples of Canada | Gatineau, QC | 2005 | 50,000 across the country in 2016 (Lanthier 2016) |

| 4. Council of First Mé]etis People in Canada | Orleans, ON | 2017 | |

| 5. Davangus Aboriginal and Métis Community | Destor, QC | 2016 | |

| 6. Kinounchepirini Algonquin First Nation | Pembroke, ON | 2011 | 14 families in 2013 |

| 7. Kitchi-Sibi Community | Gatineau, QC | 2019 | |

| 8. Maniwaki Métis Community | Maniwaki, QC | 2006, as an organization representing individuals with any or no Indigenous ancestry. It began as a local group of #10. | 6000+ in 2016 |

| 9. Mé]etis Nation of Ontario | Ottawa, ON | 1993 | At least 5000 non-Indigenous members between the 1990s and 2023. |

| 10. Native Alliance of Quebec | Local 001—Nottaway Local 008—Val D’Or Local 020—Rouyn-Noranda Local 018—Maniwaki Local 019—Otter Lake Local 023—Fort-Coulonge Local 043—Ste-Véronique Local 048—Bryson Local 050—Campbell’s Bay Local 059—Gatineau Local 060—Chapeau Local 080—Grand-Remous | 2006, as an organization representing individuals with any or no Indigenous ancestry. | 13,600 across the province in 2011 (Jung 2023); about 5000 in the region. |

| 11. Painted Feather Woodland Métis | Bancroft, ON | 2011 | 10,000 in 2016 |

| 12. Petite-Nation Weskarini People | Montpelier, QC | 2019 | |

| 13. Pontiac Aboriginal Community | Mansfield-et-Pontefract, QC | 2011 | |

| 14. Pontiac Aboriginal First Nations | Mansfield, QC | 2019 | |

| 15. Pontiac Anishinaabek Fort-de-Coulonge Kichesipirini Community | Fort-Coulonge, QC | 2010 (first an affiliate of #10, then of #3) | |

| 16. Tay River Algonquian Community | Tay Valley Township, ON | 2019 | 70 in 2021 |

| 17. Wabos-Sipi Métis Community | Mont-Laurier, QC | 2001 (first an affiliate of #10, then of #3) | |

| 18. Widjikiene Community | Casselman, ON | 2016 | 60 in 2017 (Charbonneau 2017) |

| 19. Wikanis Mamiwinnik Community | Villebois, QC | 2004 (first an affiliate of #10, then of #3) | 300 in 2016 (La Sentinelle/Le Jamésien 2016) |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Court cases in Algonquin territory and/or by an organization in Appendix A.

Table A2.

Court cases in Algonquin territory and/or by an organization in Appendix A.

| Court Case | Organization | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Quebec v. Gauthier (2011 QCCQ 12296) | Native Alliance of Quebec | Judge ruled against defendant (fishing out of season). |

| 2. Quebec v. Bechamp (2011 QCCQ 11234) | Native Alliance of Quebec | Judge ruled against defendant (fishing without a license). |

| 3. Quebec v. Paul (2013 QCCQ 17186) | Maniwaki Metis Community | Judge ruled against defendant (fishing without a license). |

| 4. Quebec v. Lachapelle (2016 QCCS 3961) | Maniwaki Metis Community | Judge ruled against defendant (hunting camp on public land). |

| 5. Abitibi Metis Camp and City of Val D’Or (2017 CMQ 65915) | Maniwaki Metis Community | Judge ruled in favour of request to forego municipal property taxes. |

| 6. Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions v. Paul (2017 QCCS 4163) | Wikanis Mamiwinnik Community | Judge ruled against defendants (moose hunting without a license and forestry violations). |

| 7. Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions v. Noël (2017 QCCS 4163) | Native Alliance of Quebec | Judge ruled against defendants (moose hunting and forestry violations). |