Multimodal Genealogy: The Capitol Hill Riot and Conspiracy Iconography

Abstract

1. Introduction

“By the way, there was Antifa, there was FBI, there were a lot of other people there too leading the charge (…) You saw the same people that I did”(Donald Trump at Sioux, Center Iowa on Friday, January 5)

2. Towards a Multimodal Genealogy

If we begin by looking, not for some universal definition of the term, but at those places where images have differentiated themselves from one another on the basis of boundaries between institutional discourses, we come up with a family tree… [which] designates a type of imagery that is central to the discourse of some intellectual discipline.

[is] not only connected forward and backward in an “unilinear” development [but] it could only be understood by what it derived from and by what it contradicted.

Methodology

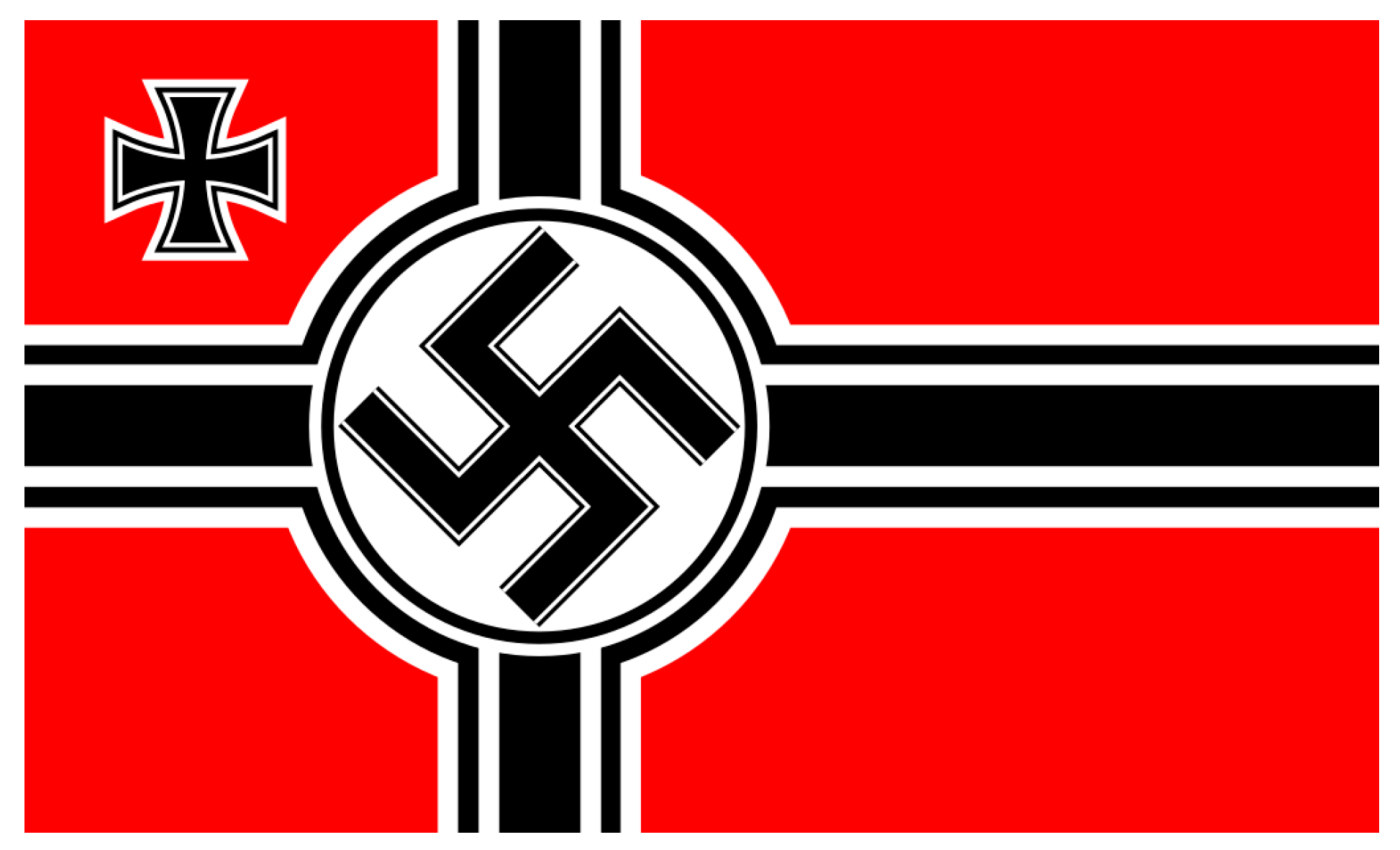

All the symbols depicted here must be evaluated in the context in which they appear. Few symbols represent just one idea or are used exclusively by one group. For example, the Confederate Flag is a symbol that is frequently used by white supremacists, but which also has been used by people and groups that are not racist’.

3. The Conspiracy of Images

Ambiguity, Hybridization, Adaptability

The “okay” gesture hoax was merely the latest in a series of similar 4chan hoaxes using various innocuous symbols; in each case, the hoaxers hoped that the media and liberals would overreact by condemning a common image as white supremacist. In the case of the “okay” gesture, the hoax was so successful the symbol became a popular trolling tactic on the part of right-leaning individuals, who would often post photos to social media of themselves posing while making the “okay” gesture. (https://www.adl.org/resources/hate-symbol/okay-hand-gesture, accessed on 9 May 2024).

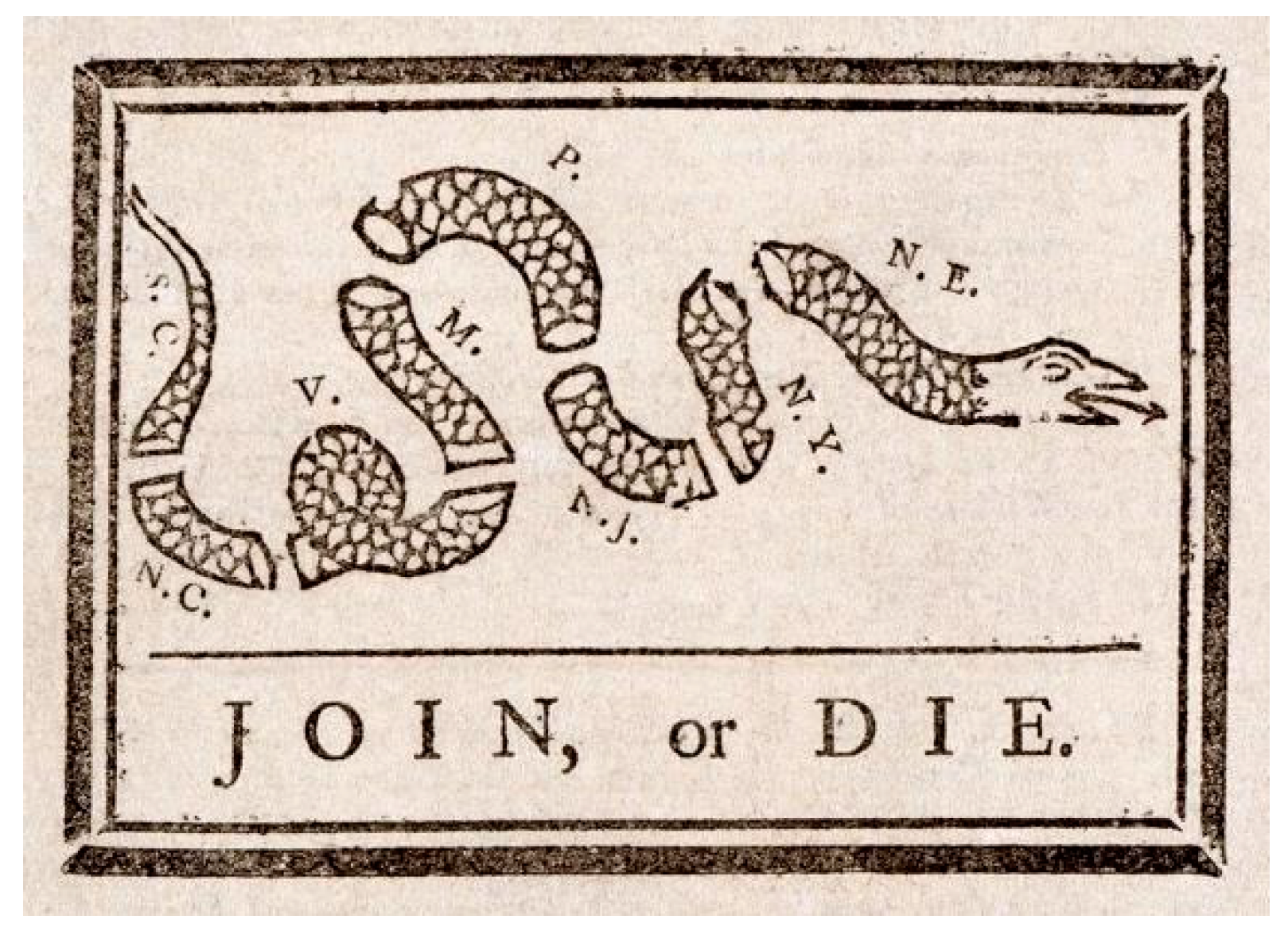

4. “Join or Die”

- Vigilance (always alert and watchful);

- Magnanimity (does not attack out of hostility but only to defend itself);

- Courage (if called upon to defend itself, it does not hesitate);

- Unity (the rattle works only if the parts are connected to each other);

- Circumspection combined with readiness to attack (teeth are hidden);

In recent years, the Gadsden flag has become a favorite among Tea Party enthusiasts, Second Amendment zealots, really anyone who gets riled up by the idea of government overreach. It’s also been appropriated to promote U.S. Soccer and streetwear brands. And this reflects a deeper question, one that’s actually pretty compelling: How do we decide what the Gadsden flag, or indeed any symbol, really means?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The full speech is available at this link: https://www.c-span.org/video/?532608-1/president-trump-holds-rally-sioux-center-iowa, accessed on 9 May 2024. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) is a non-profit organisation dedicated to assisting refugees. |

| 4 | https://projects.propublica.org/parler-capitol-videos/ accessed on 9 May 2024. |

| 5 | From now on, reference will be made to data from conversations taken from the Gab platform with the year in which they took place. |

References

- ADL. 2019. Hate On Display. Hate Symbols Database. Available online: https://www.adl.org/sites/default/files/ADL%20Hate%20on%20Display%20Printable_0.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- ADL. 2022. Andrew Torba: Five Things to Know. Center on Extremism. Available online: https://www.adl.org/resources/blog/andrew-torba-five-things-know-0 (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Baraldi, Claudio, Federico Farini, and Vittorio Iervese, eds. 2021. La facilitazione delle narrazioni dei bambini a scuola: Il progetto SHARMED. Milano: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1997. Sul concetto di storia. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2010. I passages di Parigi. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, John. 1973. Ways of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Johan, and Katherine L. Milkman. 2012. What Makes Online Content Viral? Journal of Marketing Research 49: 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, Mark. 2014. Las Vegas shooters had expressed anti-government views, prepared for l‘engthy gun battle’. The Washington Post, June 9. [Google Scholar]

- Blassnigg, Martha. 2009. Ekphrasis and a Dynamic Mysticism in Art: Reflections on Henri Bergson’s Philosophy and Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas. In New Realities: Being Syncretic. Edited by Roy Ascott, Gerald Bast, Wolfgang Fiel, Margarete Jahrmann and Ruth Schnell. Wien and New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2001. Eyewitnessing. In The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Camus, Renaud. 2012. Le Grand Remplacement. Suivi de Discours d’Orange. Available online: https://books.google.it/books/about/Le_Grand_Remplacement_suivi_de_Discours.html?id=x3EDBAAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Cassam, Quassim. 2019. Conspiracy Theories. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Coppins, McKay. 2018. Trump’s Right-Hand Troll. The Atlantic, May 28. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, Neal, ed. 2010. The Pictorial Turn. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. 1990. Devant l‘Image. Question posée aux Fins d‘une Histoire de l‘Art. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Dinoi, Alessandro. 2012. Lo Sguardo e l’Evento. Firenze: Le Lettere. [Google Scholar]

- Flori, Jean. 1999. Pierre l‘Ermite et la Première Croisade. Paris: Éditions Fayard. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1971. L‘Ordre du Discours. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, Sheera. 2021. The storming of Capitol Hill was organized on social media. The New York Times, January 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, Kelly. 2024. Day of Rage: Forensic journalism and the US Capitol riot Media. Culture & Society 46: 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Ernst H. 1986. Aby Warburg: An Intellectual Biography. New York: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell, John. 1968. Social Science and Political Reality: The Problem of Explanation. Social Research 35: 159–201. [Google Scholar]

- Harbo, Tenna F. 2022. Internet memes as knowledge practice in social movements: Rethinking Economics’ delegitimization of economists. Discourse, Context & Media 50: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, George. 2017. Making Sense of the Alt-Right. New York, Chichester and West Sussex: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iervese, Vittorio. 2016. Altro che invisibili. Il paradosso delle immagini degli immigrati. Zapruder. p. 40. Available online: https://storieinmovimento.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Zap40_14-Interventi1.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Iervese, Vittorio. 2024. La Differenza che fa la Differenza. Osservare i Processi Culturali. Milano: Mimesis. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, William. 2005. A Benjamin Franklin Reader. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable media. In Spreadable Media. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joscelyn, Tom, Norman L. Eisen, and Fred Wertheimer. 2024. Dissecting Trump’s “Peacefully and Patriotically”. Defense of the January 6th Attack. Just Security, February 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kenes, Bulent. 2021. The Proud Boys: Chauvinist poster child of far-right extremism. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies, pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Swan. 2010. The Color of Brainwashing: The Manchurian Candidate and the Cultural Logic of Cold War Paranoia. 미국학 33: 167–95. [Google Scholar]

- Konda, Thomas M. 2019. Conspiracies of Conspiracies: How Delusions Have Overrun America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Labaree, Lonard W., ed. 1961. The Papers of Benjamin Franklin. New Haven: Yale University Press, vol. 4, pp. 130–33. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leib, Jonathan, Gerald R. Webster, and Roberta H. Webster. 2000. Rebel with a cause? Iconography and public memory in the Southern United States. GeoJournal 52: 303–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, Massimo, Mari-Liis Madisson, and Ventsel Andreas. 2020. Semiotic approaches to conspiracy theories. In The Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Studies. London: Routledge, pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Majchrzak, Ann, and M. Lynne Markus. 2013. Technology affordances and constraints in management information systems (Mis). In Encyclopedia of Management Theory. Edited by E. Kessler. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, vol. 1, p. 832. [Google Scholar]

- Manghani, Sunil, ed. 2013. Images: Critical and Primary Sources. In Volume 1: Understanding Images. Oxford: Berg Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- McBain, Sophie. 2020. The rise of the Proud Boys. New Statesman 149: 26. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Idriss, Cynthia. 2022. Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Lee. 2001. Roanoke: Solving the Mystery of the Lost Colony. New York: Arcade Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, William J. T. 2013. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1986. Iconology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead, Russell, and Nancy L. Rosenblum. 2019. A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pannofino, Nicola, and Davide Pellegrino, eds. 2021. Trame Nascoste. Teorie Della Cospirazione e Miti sul lato in Ombra Della Società. Sesto San Giovanni: Mimesis. [Google Scholar]

- Parramore, Thomas C. 2001. The “Lost Colony” Found: A Documentary Perspective. The North Carolina Historical Review 78: 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Parry-Giles, Trevor, and Timothy Barney. 2020. Envisioning a Remembered Future: The Rhetorical Life and Times of The Manchurian Candidate. Journal of Popular Film and Television 48: 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perticone, Joe. 2018. How “owning the libs” became the ethos of the right. Business Insider, July 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert, Bob. 2015. The rattlesnake tells the story. Journal of the American Revolution. January 14. Available online: https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/01/the-rattlesnake-tells-the-story/ (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Schütz, Alfred. 1945. On Multiple Realities. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 5: 533–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Sant. 2018. What’s Known About Robert Bowers, The Suspect. In The Pittsburgh Synagogue Shooting. Washington: NPR. [Google Scholar]

- Solinas, Marco. 2023. Che cosa sono i cospirazionismi politici? Significazione magica, demonizzazione populista, teoria della sostituzione etnica. Jura Gentium 2: 8–36. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, James P., and Judith Holler. 2021. The Kinematics of Social Action: Visual Signals Provide Cues for What Interlocutors Do in Conversation. Brain Sciences 11: 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R. 2016. The Shifting Symbolism of the Gadsden Flag. The NewYorker, October 2. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, Aby. 1998. Gesammelte Schriften. Die Erneuerung der heidnischen Antike. Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zur Geschichte der europäischen Renaissance. Edited by Horst H. Bredekamp and Michael Diers. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. First published in 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel, Sigfried. 2015. Grammatologie der Bilder. Berlin: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iervese, V. Multimodal Genealogy: The Capitol Hill Riot and Conspiracy Iconography. Genealogy 2024, 8, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020058

Iervese V. Multimodal Genealogy: The Capitol Hill Riot and Conspiracy Iconography. Genealogy. 2024; 8(2):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020058

Chicago/Turabian StyleIervese, Vittorio. 2024. "Multimodal Genealogy: The Capitol Hill Riot and Conspiracy Iconography" Genealogy 8, no. 2: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020058

APA StyleIervese, V. (2024). Multimodal Genealogy: The Capitol Hill Riot and Conspiracy Iconography. Genealogy, 8(2), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020058