1. Introduction

During the forced march out of the labor camp in the winter of 1944, the Hungarian poet

Miklós Radnóti (

1972) was taken to a mass grave and executed. After the war, his wife exhumed his body, where, according to the coroner’s report, they found in the pocket of his raincoat a small notebook “soaked in the fluids of the body and blackened by wet earth” (

Forché 1993). The notebook, published later as the

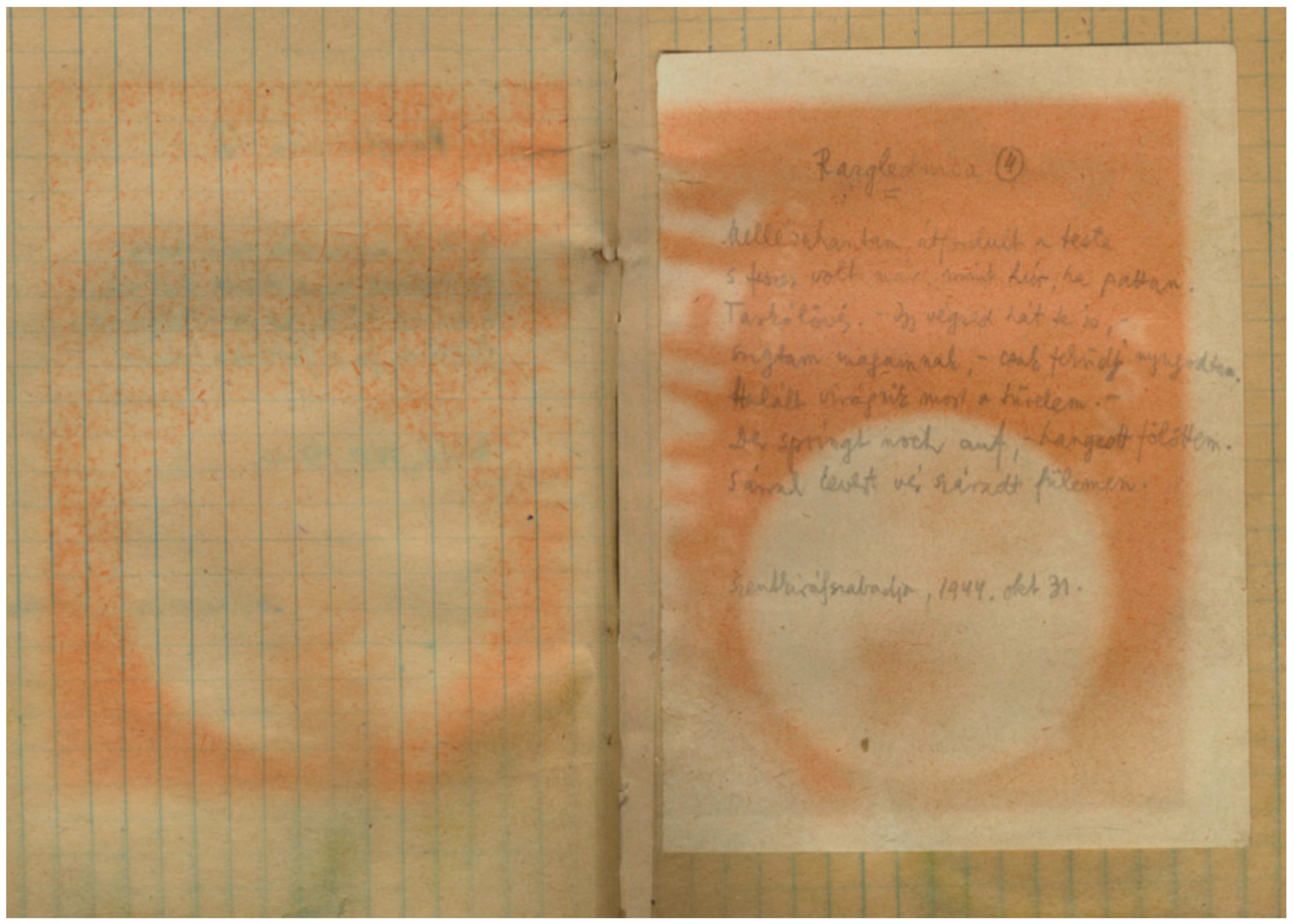

Camp Notebook (also known as the “Bor Notebook”), contains the last four of his “Razglednicas” poems, a Serbo-Croatian word for “picture postcard” or simply “postcard” with a Hungarian plural.

Postcard

4

I fell next to him. His body rolled over.

It was tight as a string before it snaps.

Shot in the back of the head―“This is how

you’ll end.” “Just lie quietly,” I said to myself.

Patience flowers into death now.

“Der spring noch auf,” I heard above me.

Dark filthy blood drying on my ear.

Szentskirályszabadja

31 October 1944

(translated by Steven Polgar, Stephen Berg, and S. J. Marks 1972)

As seen in

Figure 1, Radnóti inscribed the poem on the back of a leaflet for cod liver oil, which he inserted into the notebook (

Ozsváth and Radnóti 2000). Fluids and moisture soaked through the label so that the lettering, a rust-colored rectangle, and an image of an X-rayed hand enclosed by a striking white circle were imprinted on the page—as if the poem is trying to push free. Not “conventionally testimonial” and historically conflated with the death of his friend, the violinist Miklós Lorsi, the poem’s use of the first-person past tense nevertheless conveys the feeling of a speaker returning from the next world to tell of his own death (

Vice 2008).

Emery George (

1986) calls the final “postcard” a “ghost story”.

Władysław Panas contended that, in Polish literature, Jews were “organized around two different positions and corresponding experiences: that of the victim and that of the witness”, implying either an active or passive position (quoted in

Morawiec 2022). Indeed, it seems that, in Radnóti’s poem, the speaker’s actions are almost all happening outside of him by the force of another, as if in passivity: It is “his” (not his own) body that rolled over, it is patience that flowers, a voice that is heard above, and the dark filthy blood that dries on the ear. Even the speaker falls by force. In the poem, the only active position the speaker assumes is in his speaking within himself (“Just lie quietly”), an invocation resembling submission without foregrounding failure. Nevertheless, I agree with

Edward Hirsch (

2019) that the poem’s speaker acts neither as a witness of submission nor as a victim. Hirsch conceived of the

Camp Notebook as “literally [raised] from the grave to give testimony”. The neat, resolute pencil lines suggest a certitude. Not so much the “awkward poetics” Rowland discussed (

Rowland 2005) but rather the reflective titling of the poem “postcard” implicates an active, even defiant, position and, at the very least, complicates any rendering of the speaker as passive.

Aware that his death was unendurably near, Radnóti sent postcards from breath’s edge, his own murder frozen within the lines. Here, the physicality of the object of the poem becomes no less part of the poem than the poem itself. The blood-soaked pages “blackened by wet earth” and the story of the transference, the delivery of the poem’s message into his wife’s hands and from there into the hands of the reader, are all embedded in the poem. The poem’s object has the glow of an ember saved from ashes, and therein lies its preciousness.

Like Radnóti’s postcards, many Holocaust poets went to unspeakable lengths to write their last poems and transfer them to the world. In many instances, the poets had no way of knowing whether their poems would ever be read. Sue Vice writes “The nature of the addressee, let alone the reader, in Holocaust poetry of this kind is one of its radical uncertainties” (2008). Perhaps that is why Radnóti’s “postcards” are often understood as “ironic” (

Gosetti-Ferencei 2015;

Beck 2010;

Vice 2008). David R. Slavitt says, of the exhumation of Radnóti’s notebook, “It’s the kind of theatrical gesture that only God would have the nerve to make—if there were one” (2013).

“A poem”, Paul Celan says, “can be a message in a bottle, sent out in the (not always greatly hopeful) belief that it may somewhere and sometime wash up on land” (quoted in

Felstiner 1982).

Felman and Laub (

1991) famously agree that this kind of poetry “becomes, precisely, the event of

creating an address for the specificity of a historical experience which annihilated any possibility of address” (

Blady-Szwajgier 1991). It is hard to overlook that these poem objects traveled great distances over the abyss to arrive here on these pages.

That writers’ last Holocaust poems managed to arrive here is nothing short of miraculous. Yet, it is important to recognize that these poems did not arrive here by happenstance. Bożena Shallcross writes the following:

[I]n term of a physical object … [a] poem stands for its author, implying both the person and his or her lived experience. When considered within the context of mass genocide, a poem enters a stage of contradiction: it stands as a testimony to the dying human presence, but also to its own, often accidental, survival (2011).

Perhaps by “accidental”, Shallcross meant the random and chaotic determinant by which some poems survived and some did not. Nevertheless, we must recognize that there is nothing “accidental” about the survival of these poems. Just as Holocaust poetry translation appears “entirely transparent” (

Boase-Beier 2015), so too are the conscious means of these poems’ transference. The families, friends, colleagues, and, in many instances, entire communities had to go to unspeakable lengths to deliver them. Many times, they had to endanger themselves to do so. Furthermore, Holocaust libraries, museums, and archives had to collect, record, order, and catalogue them. They had to make the poems available. The work of deliverance itself was that of exertion and excavation. For every poem hidden in the ground, someone had to dig the poems out.

In this essay, I explore archival last poems from the Holocaust written by those who did not survive, investigating not only the poems themselves but also the stories behind them, their object-ness, and their stories of transference. Even as the poets in this article are all well-known, exploring the object-ness of their last poems and these war poems’ ephemeral nature allows for new readings and new narratives.

To investigate the objects of the poems, I engaged in conversations with Holocaust archives in the United States, Poland, and Israel as well as book publishers across the United Kingdom and Hungary. I am especially grateful to the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Central Jewish Library in Poland, the Yad Vashem Archives, Israel’s National Library, and the Archive of Ghetto Fighter’s House in Israel for their efforts in recording, ordering, and sharing these imperative poems. These poems, like urgent postcards, deliver messages to a family, to a community, to the world. They ask―what does it mean to write a poem as a last will and testament?

As is expected in last will and testaments, in these poems, nothing is expendable; every word is imperative. A man’s last words are his most rarefied. William Shakespeare delineates this notion in Richard II, act 2, scene 1:

O, but they say the tongues of dying men

Enforce attention like deep harmony.

Where words are scarce, they are seldom spent in vain,

For they breathe truth that breathe their words in pain.

He that no more must say is listened more

Than they whom youth and ease have taught to gloze;

More are men’s ends marked than their lives before. (2010)

“Where words are scarce, they are seldom spent in vain” has never rung truer than in these last poems, when even acquiring scraps of paper, a pencil, and time to write was unheard of, not to mention life threatening. To be caught writing was an immediate death sentence. Yet, that did not deter these poets. In

Man’s Search for Meaning,

Viktor Frankl (

2006) “scribbled” key words of his manuscript “on tiny scraps of paper” in Auschwitz; Rabbi Isaac Avigdor wrote poems on scraps of paper torn from cement bags in Mauthausen; Ester Srul graffitied her poem on the wall of the Kovel synagogue. Indeed, Julia Riberio S C Thomaz points to

Michel Borwicz (

1996) and Rachel Ester who consider these “traces” not merely literary events but as last wills and testaments.

I further develop the claim contended by Borwicz and Ester that these poem objects cannot be read as poems alone. To do so would erase an essential aspect of what these poems fulfil. The physical and tangible aspects of these poems are no less part of the poems than the words of which they are made up. Like legal last will and testaments whose object-ness and the corresponding formalities of their object are crucial aspects of their making (

Sitkoff and Dukeminier 2022), these last poems cannot and should not be undone from the words they carry. Thomaz states “The case for reading war poetry as ephemera” war poetry as a means of organizing experience, “leaves traces behind and [bestows] sense upon the world” (2024).

Reading last poems as wills and testaments delineates vastly varied accounts of these poem objects. In place of a homogenous approach, in his book

Final Judgments, Edward Champlin suggests that last wills and testaments are an “extraordinary window” into the individual’s mind (

Blady-Szwajgier 1991). Champlin considers a whole “universe” of motives, wishes, duties, fears, and pressures, which the will and testament seeks to alleviate and fulfil (

Blady-Szwajgier 1991). The last will and testament can be a perfunctory disposition of property, it can be an emotional calling from beyond the grave, it can be both, and it can be every shade in between. The narratives last wills and testaments invoke are as infinite as the variations between poets. Indeed, this essay builds upon Champlin’s approach to investigate the last poems not as a uniform narrative of “traces” but rather notices of how each last poem produces its own, distinct narrative as a last testament.

2. Results and Discussion

In this article, I will discuss the last poems of four poets, Władysław Szlengel, Selma Meerbaum-Eisingerb, Hannah Szenes, and Abramek Koplowicz, even though, as is found in many cases of Holocaust victims, not much is known. This essay centers on the stories of the poets and their last poems. To borrow from (

Aarons and Berger 2017), “it is this periphery upon which the third-generation trespasses in an attempt to capture memory and fill the ever-widening gap”. Indeed, this essay attempts to “capture memory” and claims that each of these poets creates, explores, and expands new narratives of what it means to write a poem as a last will and testament. Each poet is bound by their individual “universe” of motives, wishes, duties, fears, and pressures. Crucially, these poem objects differ in their stories of their object-ness and, therein implicitly, what their objects seek to fulfil in the world. Therein, as I read these last poems, I explore the relationship between the poems as works of literature and as physical objects.

2.1. Władysław Szlengel

Whereas Radnóti’s “postcard” poem was read as a ghost story, a poem raised to give testimony not as a victim but as a witness of its own submission to death, Władysław Szlengel’s last poems give testimony on the nonacceptance of death by another outside of oneself. The Polish poet Szlengel was deeply involved in the Jewish uprising in the Warsaw ghetto. He was motivated by the image of the Jewish fighter, so much so that Arkadiusz Morawiec follows Panas and Hannah Krall as he claims that, in Szlengel’s poems, death “does not unite people, it divides them”, juxtaposing the “beautiful death” associated with revolt and uprising and the “unimpressive” death of those who fear (2022). Szlengel’s poem “Two Deaths” overtly supports this claim (

Szlengel 2012).

Szlengel’s death is a source of great mystery, of which many accounts have been given. Morawiec traces in great detail the confused, at times contradictory accounts: Was Szlengel “buried by the walls of the destroyed Jewish quarter” (

Maciejewska 1988), or buried in the “demolished basement” of 38 Świętojerska Street (

Urzykowski 2013)?

Halina Birenbaum (

1998) writes in her diary “Szlengel, as is known, died in a bunker during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising”. Was he executed (

Stańczuk 2006;

Engelking and Leociak 2009)? And if he was not killed in the ghetto, did he board the transport to Treblinka (

Morawiec 2022)? And if Szlengel boarded the transport, did he take “poison” or “a cyanide pill” on his way to the extermination camp (

Grynberg 1984;

Gross 1993)? These are questions that have yet to be resolved, and perhaps, we will never, can never know.

We do know that Szlengel took great care to preserve his poems. He gave copies of them to an unknown individual who stored them inside the double top of an old table. Ryszard Baranowski discovered them after the war when he “demolished” the table (

Shallcross 2011). Szlengel asked Henryk Krzyczkowski, a Home Army soldier and a chemist, to store a copy of his poems, and Krzyczkowski agreed to do so (

Skwara 2003). He created many carbon copies, and finally, he recited his poems to his fellow ghetto inmates. The fellow inmates recited the poems, perhaps explaining the many variations in some of them. Birenbaum recalled the following:

[T]he poems of Wladyslaw Szlengel were read in the houses of the ghetto and outside, in the evenings, and were passed from hand to hand and from mouth to mouth. The poems were written in burning passion as the events, which seemed to last for centuries, occurred. They were a living reflection of our feelings, thoughts, needs, pain, and merciless fight for every moment of life (quoted in

Kassow 2007).

Most incredibly, Szlengel’s poems were preserved as part of the

Oyneg Shabas Archive, led by the historian Emanuel Ringelblum in the Warsaw ghetto, a collection of witness testimonies, poems, essays, artifacts, photographs, diaries, and ephemera. Ringelblum writes “If none of us survives, at least let that remain”. Too many archival core participants died in the war, including Ringelblum.

Peter N. Miller (

2013) called the staggering archive “a vision of material culture as life itself”. The archive was divided into three parts: the first stored in metal boxes, the second stored in milk cans, and the third never found.

Figure 2 shows one of the milk cans used by Oyneg Shabas to store part of the archive.

In

Oyneg Shabas, we find some of Szlengel’s last poems. Frieda W. Aaron writes that Szlengel did not date his poems, but their dates were learned through context (1990). According to the Jewish Historical Institute, Szlengel wrote his last poems between January 1943 and April 1943. These poems reflect “the growing awareness of the conflagration—an epiphany that provoked many poets to use their poetry as a call to armed resistance” (

Aaron 1990). Yet, that “epiphany” should not be overshadowed by Szlengel’s conscious knowledge, not premonition, that the armed resistance would fail. His last poems are some of the last ones from the Warsaw ghetto. Szlengel well understood that responsibility (

Shallcross 2011).

His poem “Five Minutes to Midnight!!!,” as seen in

Figure 3, paraphrases Adam Mickiewicz’s poem “Reduta Ordona”, depicting the Warsaw Battle of September 1831 (

Shenfeld 1987):

Five minutes to midnight!!!!!!

We weren’t told to go down.

Into the attic like cats—up the ladder

We jumped sweaty and fearful.

Waiting for night—from six in the morning

We who ingest hours of despair,

huddled together in our cells—flat on the roof.

…

I curse for those who can no longer curse

And for those, who won’t hear the wake-up call,

Songs of freedom over the city walls,

Cry out. O, You who are equal to the gods;

Arise to action— from despair and sadness!

The time is near—five minutes to midnight.

The poem’s minimal water damage endures only traces of its effortful deliverance and is in itself a testament to the ingenuity of architects of the Oyneg Shabas. The poem is typed in purple ink, which was fashionable at the time. Yet, though the poem is typed, its paper bears pen markings in more than a handful of places, remedying spelling errors and revising grammar structures and punctuation marks. These markings suggest that the poem was typed in great haste and that, once the poem was typed, either the architects of Oyneg Shabas or Szlengel himself reread the piece. Therefore, the poem reads more like a desperate need for action than a carefully planned meditation, a reading that is only enhanced by the uneven (for example, in some places, Szlengel uses five ellipses and in some places eight), disparate (for example, one line contains a period followed by a dash), and dramatic punctuation (for example, the title of the poem contains six consecutive exclamation points). In other words, if Radnóti’s poem was a will and testament to a certitude in submission to death by another, Szlengel’s poem was a will and testament of desperate nonacceptance of death by another. Whereas Radnóti’s poem lies silently, as if in meditation, Szlengel’s poem cries out in alarm. “Fight!” it commands us, and we must heed.

2.2. Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger

Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger was only eighteen when she died of typhus in a labor camp on 16 December 1942. The then Austro-Hungarian, now Ukrainian, city of Czernowitz was under Romanian rule when Meerbaum-Eisinger was born. In that sense, Meerbaum-Eisinger was born into a multiethnic and multilingual tradition with a particular devotion to her Austrian heritage and the German language (

Meerbaum-Eisinger 2008). Her poetics were deeply reflective of her lineage: her one and only collection,

Blütenlese (translated to Harvest Blossoms), contains fifty-two original poems and five translations from Yiddish, French, and Romanian into German (

Blau 2009). The English translation,

Harvest Blossoms, includes one additional translation of a poem from French to Yiddish. The final translation appeared in the last letter Meerbaum-Eisinger ever sent, and it was first printed by Hersh Segel, who was Meerbaum-Eisinger’s teacher in her Yiddish school (

Segel 1977).

It could be said that Meerbaum-Eisinger’s entire body of work was her last. With too embryonic a career to have even truly begun, Meerbaum-Eisinger saw not even a single one of her poems printed. She had no notion that such a wide readership would read and experience her poems and translations. Her reader was an audience of one: His name was Leiser Fichman. Leiser was Meerbaum-Eisinger’s first love and first heartbreak. She dedicated the collection to him, as seen in

Figure 4, writing the following:

To Leiser Fichman, in remembrance and thankfulness for a lot of unforgettable beauty, dedicated with love (

Pearl Fichman 2005).

In 1942, she gave the handwritten and hand drawn collection, collected and organized only days before Meerbaum-Eisinger departed for Michailowka, to her friend Elza, hoping against hope that Elza would find a way to deliver the collection to Leiser, who had already been deported to a labor camp (

Meerbaum-Eisinger 2008). There are conflicting accounts of whether Leiser received the collection while he was in the camp. Pearl Fichman writes that he only received the notebook “when [he] returned from the labor camp” (2005), whereas Jürgen Serke wrote that Leiser took it with him to the Lager “and kept it among his things” (

Serke and Meerbaum-Eisinger 2005). Either way, after receiving the manuscript, Leiser returned it to Elsa for safekeeping. Leiser is claimed to have said “I … don’t want Selma’s poems to be lost if I do not make it” (quoted in

Meerbaum-Eisinger 2008). Leiser’s fear arose as he boarded the ship to Palestine,

Mefkure, which sank at sea. He never learned of her death (

Pearl Fichman 2005).

Although he had no knowledge of Meerbaum-Eisinger’s death, Leiser fully knew how she felt about him. Her poems reached him in the nick of time, only a short while before he died. Shmuel Huppert believes the entire collection was edited out of her “intention to express the intimate dialogue with her beloved, who rejects her, and with the world that threatens her life” (

Meerbaum-Eisinger 1983). Indeed, many of the poems in the collection reflect a love deeply and sensually experienced as well as the agony of heartbreak. Irene and Helene Silverblatt write “Selma’s poems address the desires of a young woman in love” (

Meerbaum-Eisinger 2008). Pearl Fichman discusses the poems’ themes as reflecting, among other aspects, an “all consuming love for Leiser, who seemingly did not reciprocate her ardor” (2005).

Meerbaum-Eisinger’s

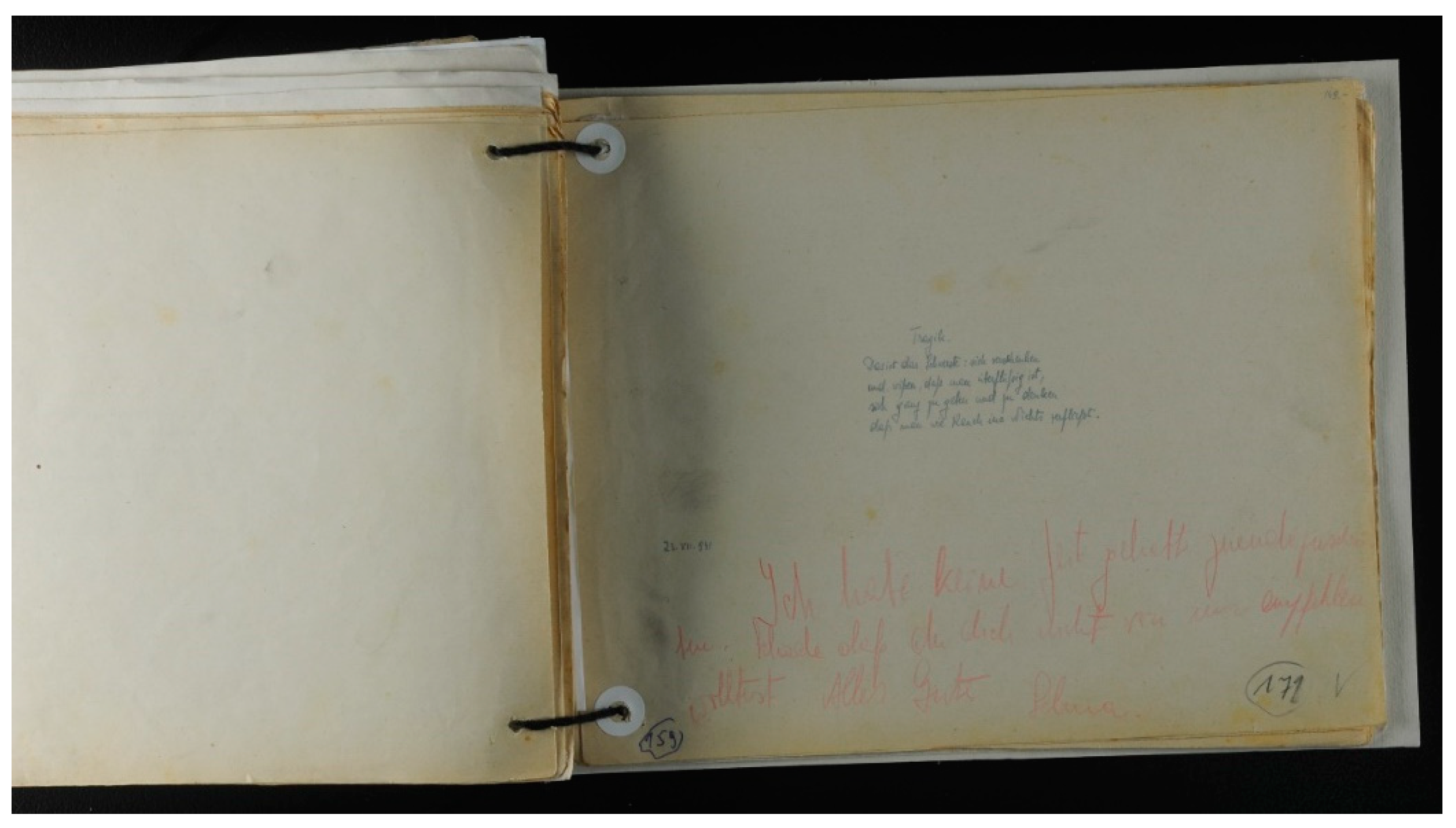

Harvest Blossoms is not chronological; nevertheless, the final poem of the collection, dated 23 December 1941, coincides with one of her last documented poems. The poem,

Figure 5, reads as follows:

Tragedy

This is the hardest: to give yourself away

and then to see that no one needs you,

to give all of yourself and realize

you’ll fade like smoke and leave no trace.

(trans. Jerry Glann and Florian Birkmayer, with Helene Silverblatt and Irene Silverblatt,

Meerbaum-Eisinger 2008)

The collection’s dedication, “with love”, dramatizes the reading of the “you” not as a lyrical or removed “you.” In “Tragedy”, the “you” is more intimate than even the “I”. The reader is privy to the conversation a young woman has with herself, what her “I” whispers to herself when no one is near. In much the same way, the “no one” in the poem is closer to a “someone”, an altogether nearly explicitly named someone, even as he needs no naming. The speaker’s “you” speaks their deepest fear and most difficult truth, the knowledge that a certain “no one” has left a deep scar on their heart, all while recognizing that they have left no trace on theirs.

Then, in a painful move, Meerbaum-Eisinger adds under the poem a personal note to Leiser. She writes this personal note in red pencil with much larger lettering than the poem. The note reads “I didn’t have time to finish writing. It’s too bad you didn’t want to say goodbye to me. I wish you the best” (

Meerbaum-Eisinger 2008). The personal note not only bookends the entire collection with Leiser but also creates a reading of the entire collection as a long-form letter with a known addressee. If a poem can be a last will and testament, then for Meerbaum-Eisinger, the poem was never intended for the world to read; it was written only for Leiser and him alone.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to narrow the gaze so intently. To read Meerbaum-Eisinger’s poem wholly as a personal address removes the poem from the historical circumstances in which it exists and flattens its doubling effect: The personal embodies the historical; the historical embodies the personal. Throughout the collection, as in “Tragedy”, Meerbaum-Eisinger made layered allusions to the Holocaust. Poetic choices, such as the use of “smoke”, cannot be read without conjuring the image of the many chimneys erected across Europe during those years. Did Meerbaum-Eisinger know what horrific destiny awaited the Jews who were loaded into the transport?

We will never know with certainty what Meerbaum-Eisinger knew or what she truly intended for her poems. Meerbaum-Eisinger died in a labor camp without knowing whether the poems reached Leiser. We learn of the details of her last days and her death from a drawing and diary entries by her fellow inmate, Arnold Daghani. Daghani wrote, on 16 December 1942, “[Selma] became even smaller and weaker. Then it was still.” (quoted in

Meerbaum-Eisinger (

2008)). Her death was a tragedy, yet it cannot be said that she, the poet, inhabits the space of poem “Tragedy.” More than eighty years after her death, Meerbaum-Eisinger’s work has not faded but has instead left such a significant “trace”. Irene Silverblatt and Helene Silverblatt write the following:

[W]e like to think that in the very act of writing “Tragedy” Selma tricked tragedy, renounced it, even if “not always greatly hopeful” that she had succeeded. Miracle or no, her poetry has come on shore right here; it is still talking, still part of the world, still connecting human beings across decades and continents, still grabbing life (2008).

That Meerbaum-Eisinger’s poems “tricked tragedy” was no “miracle”. The manuscript was saved many times over by many hands. First, by Meerbaum-Eisinger herself, who gave the manuscript to Else, who managed to deliver it to Leiser, and then by Leiser, who did not or could not take the manuscript with him onboard the Mefkure and so returned it to Else. Else then gave the manuscript to Renée Abramovici-Michaeli, who carried it on the arduous journey from Europe to Israel. Serke writes the following:

With Selma’s collection in her rucksack, Renée made her way through Europe. By foot, by horse-wagon, by roofs of passenger trains, through Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, through Austria, through Germany to Paris. In 1948 landed on a ship to Israel, the poems in her hand luggage. The suitcase that she sent ahead was lost (2005).

Even if we read Meerbaum-Eisinger’s poems as a will and testament with an intended readership of one, Leiser, we should not overlook that her friends and, indeed, her community poured behemoth efforts into her readership’s expansion and drew power from the poems. In a letter sent to Renée, a mutual friend writes the following on 30 December 1946:

… I had in my possession the collection of [Meerbaum-Eisinger’s] poems. These poems are now in the right hands—yours. And the poems were she herself! And now I ask you, was I allowed to read them those poems that were not meant for me but were meant for only one, who now rests on the wide ocean floor. … Nevertheless, I read and read the poems! I drew the right and the permission from the image of the person that lives within my heart, the person that I loved will always love in all her depth and in all the holiness of a first experience …” (

Meerbaum-Eisinger 1983).

The question “was I allowed to read them those poems that were not meant for me but were meant for only one, who now rests on the wide ocean floor” is a question for which, perhaps, there is no answer. Nevertheless, there is truth in what architect Hammerling purportedly said of Meerbaum-Eisinger’s poems: “You are a blossom, whose fragrance will brighten in the future the heart of the whole world” (

Meerbaum-Eisinger 1983). Intended or not, Meerbaum-Eisinger’s poems as last testament “brighten[ed]” the world.

2.3. Hannah Szenes

Many debates have arisen regarding the intention of Szenes’s poems and the nature of her figure. Was she a national poet for Israel, whose poems were explicitly and deliberately structured as heroic and mythical calls for action (

Glick 2020), or did her poems reflect personal frustrations, difficulties, and defeats to be posthumously co-opted as heroic and mythical calls for action (

Baumel-Schwartz 2010)? These positions are less antithetical than they at first glance appear. Szenes’s poems sustain both readings. It is possible that Szenes’s poems were structured as an intimate personal address, expressing complex emotions, such as frustrations, difficulties, and defeats, and simultaneously structured (and then co-opted or corrupted) as patriotic calls for action.

Szenes’s complex and layered biography sustains both readings of her poems. Born in Hungary, Szenes became a Zionist in her late teens and moved to Yishuv in Mandate Palestine in 1939. By 1941, news of the dire condition of the Jews in Eastern Europe had reached Mandate Palestine. Szenes pleaded with her mother to emigrate out of Hungary, but her mother was unable to make the passage. Completely cut off from her family, in 1943, Szenes volunteered to be a parachuter in the British Army. She dropped into Yugoslavia in 1944 in an attempt to cross over into occupied Hungary. She was captured, jailed, interrogated, and relentlessly beaten and tortured in a bid to find information about her unit’s radio transmitter. “But she did not talk”, wrote

Candice F. Ransom (

1993). Her refusal to “talk” was mythologized even while she was alive and certainly after her death. In his biography,

Anthony Masters (

1972) writes the following:

Amongst other methods of chastisement, they continued to beat her on the palms of her hands and the soles of her feet. They stripped her and then beat her. They pulled out her hair in fistfuls. They knocked out a tooth. And they bound her in a sitting position, flogging her for hours. Was this martyrdom? wondered Hannah. Was this the price she had to pay for years of idealism? She began to realise that it was.

Szenes’s sacrifice only increased in stature and ballooned to legend when her mother was arrested and held in Szenes’s prison as a means of torture, yet Szenes did not reveal any information. Yoel Palgi, a fellow comrade, writes the following:

Still Hannah would not yield. I was completely shattered on hearing her story and stared at her in astonishment. How could she have remained so resolute and calm? Where did this girl, who loved her mother so much, find the courage to sacrifice her, too, if necessary, rather than reveal the secret that was not hers, that affected the lives of so many? As it was, Hannah’s fortitude saved her mother. Had she broken down, they would doubtless have executed her immediately and sent her mother off to the gas chambers of Auschwitz (

Senesh et al. 2004).

Szenes was accused of treason in a sham trial, after which a firing squad executed her. In the wake of her death, her mother would be left wondering whether her daughter volunteered for the fateful mission to save her or to fight for her country, a question she would have no simple answer for. After Szenes’s execution, her mother was given her dress. In the pockets of the dress, she found two scraps of paper. The first was an undated creased note to Szenes’s mother. The handwritten note, as seen in

Figure 6, reads as follows:

Dearest Mother:

I don’t know what to say—only this: a million thanks,

and forgive me, if you can.

You know so well why words aren’t necessary.

With love forever.

Your daughter

The handwriting is neat and written in unwavering lines, which suggest an assuredness. Her direct style fills the scrap of paper in its entirety, lending to Szenes’s aura of staunch devotion to her mother as well as the doubled determination in her choice.

The second scrap of paper was Szenes’s last poem, herein in

Figure 7. Her mother describes the poem, writing “[Szenes] must have written in her cell in Hadik Barracks after our last meeting” (

Senesh et al. 2004). The poem was written four and a half months before her execution, and it reflected her doubt that she would be let out of her jail cell alive. She writes the following:

One—two—three …

eight feet long,

Two strides across, the rest is dark …

Life hangs over me like a question mark.

One—two—three …

maybe another week.

Or next month may still find me here.

But death, I feel, is very near.

I could have been

twenty-three next July;

I gambled on what mattered most.

The dice were cast. I lost.

20 June 1944

(trans. Peter Hay, Eitan Senesh, David Senesh, and Ginosra Senesh)

Here, too, the handwritten words stretch from one edge of the scrap to the other: filling the space in its entirety. Here, too, the handwriting is clear and even, and it bears no markings of hesistation, erasues, or doubt. The resolute physicality of the object as well as its siginture and date add to reading as a certain kind of last will and testement.

The poem’s three quatrains build on their play with time (

Davidovich 2013), in which the game’s end is predetermined. In the original Hungarian, the poem is skillful in execution of form and rhyme. Its physical conjoining with Szenes’s note to her mother moves the poem beyond the “literary” realm, as Thomaz suggests (2024). The poem is (and must be) read alongside its companion farewell note to Szenes’s mother. Therefore, the poem cannot be read for its aesthetic qualties alone; rather, it must be read as an elucidation of a daughter’s mental calculations. In the poem, Szenes explains to her mother why she made the choices she did without wholly answeing. Szenes writes “I gambled on what mattered most”, and yet, the poem leaves open and unresolved what mattered most—was it saving her mother, saving her country, or both?

2.4. Abramek Koplowicz

The Polish poet Abraham (Abramek) Koplowicz was only fourteen when he was murdered in Auschwitz. Originating in Lódz, his family, along with many of the city’s Jews, was forced into the ghetto. (Jackie Metzer (n.d.) writes “The next four years with his mother and father in the ghetto effectively ended the happiness of a short childhood”. In the ghetto, young Koplowicz worked in the shoe factory, where he endured constant hunger and terrible fear. In 1944, the ghetto was liquidated, and the Jews were transported. Koplowicz was transported together with his father to Auschwitz. In Auschwitz, his father had to leave the camp to do hard labor. Taking pity on his son, he concealed him in the hut, which housed several hundred prisoners. When Koplowicz’s father returned from the day’s work, he found his son’s bed empty. He had been taken to the gas chamber. “It’s possible”, writes Eliezer Greenfelt, Koplowicz’s half-brother, “that [his father] saw himself as guilty for the death of his son, and thereby was reticent [from there on out]” (

Koplowicz 1995).

Once the father, grief stricken, returned from Auschwitz to their home in Lódz, he found in the attic, untouched by time, his son’s painting and exercise book, filled with eight poems and two short plays. The father said almost nothing about Koplowicz. These poems managed to survive and were discovered by Greenfelt only after his stepfather’s death. Nevertheless, since Greenfelt’s discovery, he devoted his life to Koplowicz’s legacy. It became “his life’s work” (

Carmon 2020). Koplowicz’s most well-known poem is his penultimate one, titled “Dream,” herein

Figure 8:

Dream

When I will be 20 years old,

In a motorized bird I’ll sit,

And to the reaches I’ll rise.

I will fly, I will float to the beautiful

faraway world

And skyward I will soar,

The cloud my sister will be

The wind is brother to me.

…

The handwritten poem is, like Szenes’, neat and unwavering. Yet, the handwriting style stands in stark opposition to Szenes’. Instead of connoting determinacy, the handwriting, with its stylistic lettering and simple drawings, reminds the reader of its still blossoming, still becoming author. In particular, the heart etching at the poem’s edge serves as a deeply touching gesture of an unfinished life.

I’m aware that this isn’t a great piece of work. It shows promise. And it is, of course, a fiction, a dream of impossible mobility, pleasurable freedom and an adult future which contains almost nothing but wonder.

Kennedy examines the poem in its capacity as a finished, polished, mature conception of language and compares the poem to what it could have been. It is a rendering of the poem outside itself. Within what

Joanna Beata Michlic (

2017) calls “the impossibility of the recovery of childhood”, the poem’s light is its unfulfilled promise, a language that has yet to reach maturation. Adam Shiffer calls Koplowicz “the spark that didn’t attain flamehood” (

Koplowicz 1995). Comparisons to mature writers are frequent. Shiffer contrasts Koplowicz and his innocent poetic ability to hold onto life with Szlengel, who “reads to the dead”. Zbigniew Dominiak compares Colonics to poets such as Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński, Tadeusz Różewicz, and Jerzy Kosiński (1995). They ask what could have been had he lived.

Yet, this poem resounds, most prominently, in the writer’s address to himself, which did not (and could never) arrive. The poem goes beyond itself and speaks back to the poet, beyond imagined futures, which have “almost nothing but wonder”. As if responding to Radnóti’s definition of “postcards”, Koplowicz’s poem’s deepest knowledge lies in its impossibility: a child knowing that he is a child and knowing with certainty that he will not become the adult he could have been, knowing his language will not mature, will not be fulfilled. For Kolpowicz, his last poem as a will and testament, addressed above all to himself, to who he could have been, is a knowledge of its own unbecoming.

3. Conclusions

If these last poems are last wills and testaments, then for each poet, that testament meant something wholly their own with its own “universe” of motives, wishes, duties, fears, and pressures (

Champlin 1991). In place of an approach to poetry war ephemera as a unified conception of a last will and testament, this essay explored the vastly differing narratives that arise out of reading these poems as testaments. Radnóti’s poem was a ghost story, a poem written to give testimony not as a victim but as a witness of its own submission to death; Szlengel’s last poems give testimony regarding the nonacceptance of death by another outside of oneself; Meerbaum-Eisinger’s poem was a desperate attempt to tell a lover how she felt; Szenes’s poem was an explanation to a mother of Szenes’s motives for sacrifice; and Koplowicz’s poem was a letter to a future self he would never become.

Aware that their deaths were unendurably near, these poets crafted their last wills and testaments as poetry, and they took great care with their words. “When words are scarce, they are seldom spent in vain”, wrote Shakespeare in Richard II (

Shakespeare and Bate 2010). What could ring with more ferocity, more urgently then Radnóti’s “Patience flowers into death now”; Szlengel’s “The time is near”; Meerbaum-Eisinger’s “This is the hardest”; Szenes’s “I gambled on what mattered most”; and Koplowicz’s “The cloud my sister will be”. We are commanded to hear each voice as it was, recognizing the uniqueness of each poetic address. These readings are possible, become possible, only as we fully grasp the “object” of these poems and their extraordinary means of communication.

Like a legal last will and testament, in which the physicality of the document is inherently crucial to its making, so too is the tangibility of these last poems crucial to their making, in particular, considering the incredible difficulty of creation, excavation, and delivery of these poems—from the poet into the hands of the family, the community, the nation, and the world. Radnóti’s handwritten poem imprinted on the image of an X-rayed hand: a poem trying to push free. Szlengel’s poem, hastily typed in purple ink with its uneven punctuations and many revisions, reads like a frenzied need for action. Meerbaum-Eisinger’s addition of a personal note in red to Leizer reminds the reader that the poem object is meant for an audience of one. Szenes’s handwritten, assured, and determined poem and note to her mother fills the space of the scarps in their entirety, yet still leaves unresolved what mattered most—was it saving her mother, saving her country, or both? Finally, Koplowicz’s poem, with his stylistic handwriting and small drawing, allows for a reading of his last poem as a will and testament, addressed above all to himself, to who he could have been, in heartbreaking knowledge of its own unbecoming.

When we recognize the physicality of these poems as inextricable from the words of these last poems, so too becomes apparent the work of transference of these poem objects. As Celan said, these poem objects become those “message in a bottle, sent out in the (not always greatly hopeful) belief that it may somewhere and sometime wash up on land” (quoted in

Felstiner (

1982)). “[Wash] up on land” they did, and their survival was accomplished by many hands. The very act of exhumation, like in the instance of Radnóti’s wife who exhumed her husband and discovered the “Bor Notebook” and the exhumation of Szlengel’s poem from the cannister in the

Oyneg Shabas Archive, is itself no less part of poems then the poems themselves. In many cases, family members had to devote their entire life’s work to the delivery of these poems, like with Szenes’s mother and Koplowicz’s father and half-brother. In other cases, an entire community banded together to deliver the poems, here, to these pages. So much can be seen in the unyielded effort of transfer, from one hand to another, of Meerbaum-Eisinger’s

Harvest Blossoms between her many friends, among them Leiser himself, who all worked together across years and continents to deliver the poems to the archives of Yad Vashem. That these poem objects traveled great distances to arrive here on these pages is nothing short of a revelation, and we must recognize that this is merely the start of these poems’ journeys.