Abstract

Recent research in social psychology underscores the role of language and its intersection with other identity markers, including ethnic visibility, in exploring social perceptions and biases. This paper examines the physical visibility of people of Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) descent in the U.S., and the linguistic visibility of a concentrated MENA American community in Dearborn, Michigan. Relying on headshots, Study 1 shows that MENA could be an ambiguous ethnic community based solely on physical appearance, while religiously affiliated attire proves to be a significant ethnic marker for MENA. Using audio cues, Study 2 shows that the English variety spoken in Dearborn is a recognizable variety with masculinity associations. As such, Dearborn English is argued to be an ethnolinguistic repertoire that can be used to project ethno-local visibility. The results highlight the importance of the linguistic visibility of Dearborn and future research on language attitudes towards this variety.

1. Introduction

The consensus among many biologists and social scientists is that distinctions among ethnoracial groups are not genetically discrete or reliably measurable (Cartmill 1998; Feldman 2010; Koenig 2010; Lewontin 1991, 1996; Littlefield et al. 1982). While ethnoracial distinctions cannot be biologically reliable, they are historically significant and have important social implications for different groups (Smedley and Smedley 2005). As such, ethnoracial groups are socially constructed and individuals often get placed into certain categories based on indexical markers such as phenotype and language. The intersection of ethnoracial visibility and linguistic behavior has long been studied in social psychology (e.g., Giles and Bourhis 1975, 1976) but is still an under-studied topic in the field. There are several accounts of how individuals get cast into codified ethnoracial categories based on how they look, accompanied by how they or their names sound (see, e.g., Alim’s (2016) transracial experiences, or Shrikant et al.’s (2022) account of forms of racialized violence as a result of being placed into federally defined categories, or assigned phenotypic features). Our social perceptions place individuals into codified groups or communities and taxonomically collapse their linguistic (e.g., accent) and their non-linguistic practices (such as their sartorial choices) (e.g., Rubin 1992; Rakić et al. 2011, 2020). At the same time, from a bottom-up perspective, the performative agency of the members of a given community (either linguistically or non-linguistically) interacts with their sense of visibility (again, both linguistically and non-linguistically) (e.g., Hoffman and Walker’s (2010) argument of how they think ethnic visibility could have influenced Chinese Canadians’ ethnic orientation in Toronto). In other words, only after a community is noticed does its members’ performative agency, or lack thereof, become socially meaningful. At the same time, ethnic visibility could be solely linguistic.

In fact, language and accent are among the core markers of ethnicity and ethnic affiliation. The biblical story of shibboleth shows that vocal cues (i.e., individuals’ accents, as in the replacement of /ʃ/ with /s/ in the word shibboleth by the Ephraimites) have been used by humans as a marker of in-group and out-group memberships throughout history. Studies have shown that vocal cues are a more reliable index marker of ethnicity than visual cues (Kinzler et al. 2007; Pietraszewski and Schwartz 2014). In response to such vocal cues, listeners often form evaluative reactions which are generally called language attitudes by linguists and social psychologists (e.g., Preston 1998). Dragojevic et al. (2021) defined five major and distinct lines of research within the literature on language attitudes: documentation (documenting such attitudes); explanation (explaining such attitudes and identifying the major causes for such attitudes); development (changes of attitudes over time and contexts); consequences (social consequences such as discrimination, language maintenance or erosion, etc.); and change (interventions that can influence language attitudes over time). A large number of studies within the documentation line of research have shown that low-prestige vocal cues (i.e., varieties associated with speakers of low prestige based on social evaluations of locality, ethnicity, immigration status, gender identity, sexual orientation, etc.) are less favorably evaluated cross-culturally (see Dragojevic et al. (2017) and Lindemann (2005) for language perceptions on non-native English; Coupland and Bishop (2007), Cramer (2016), and Preston (1998) for evaluative judgements about regional English in the U.K. and the U.S.; and Giles and Watson (2013) for a comparative global perspective on social judgments about languages and varieties and their speakers).

These evaluative judgments towards language varieties and their speakers can have major consequences within the broader social context (mostly negative consequences for ‘non-standard’ varieties). These negative consequences affect speakers of both non-native varieties and low-prestige native varieties in different contexts such as education (Calamai and Ardolino 2020) and employment (Gluszek and Dovidio 2010). As such, intervention programs aimed at improving language attitudes are essential, and studies have shown that such intervention programs seem to moderate negative evaluations of speakers of low-prestige varieties (Bozoglan and Gok 2016; Roessel et al. 2019; Wolfram and Schilling 2015). However, the first step and “an important springboard” (Dragojevic et al. 2021, p. 64) in this direction is the documentation of language attitudes towards particular varieties.

At the same time, we should note that out-group listeners’ evaluative reactions to minoritized varieties and minority speakers’ use of certain vocal cues (when they do so) are contemporaneous and happening simultaneously. Once speakers note that their community in general, and their language variety in particular, have been noticed (either by in-group or out-group members), their linguistic behavior becomes socially meaningful in that they can consciously signal (minority) group membership via their vocal cues. This is actually the central question of the ethnolinguistic identity theory: why is it “that in certain situations some members of a group accentuate their ethnolinguistic characteristics … while others converge toward” out-group speakers (Giles and Johnson 1987, p. 69)? For under-studied communities, such as Americans of Middle Eastern or North African descent (MENA Americans for short), an initial step (even prior to the documentation of language attitudes towards their varieties) is to study their visibility before we can study their performative behaviors or out-group evaluative reactions to such behaviors. Therefore, the present study explores the visibility of people of MENA descent based on physical features in the U.S. context, and the linguistic visibility of Dearborn, a concentrated MENA American community in southeastern Michigan. In the next section, I will briefly review the socio-historical and political issues around MENA as an ethnic category and present the motivation for the studies in the present paper.

2. Context: MENA and Whiteness

MENA Americans have historically and legally been classified as white despite the social perception that they are not white (Beydoun 2015; Khoshneviss 2019; Maghbouleh 2017). Early immigrants from MENA regions were identified by the U.S. government as “Turks” or “other Asians” up to 1920 (Marvasti and McKinney 2004); however, the legal classification of immigrants from MENA gained more importance when the early immigrants tried to obtain naturalized citizenship. Such importance (as well as the disjunction between being legally classified white and socially classified as non-white) can be exemplified in the case of George Shishim, an immigrant from the Mount Lebanon province of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1909, Shishim had to fight a legal case in California in order to prove that he was white and therefore eligible for naturalization. The 1790 Naturalization Act had clearly stipulated that one had to be “a free White person” in order to become a naturalized citizen. What had started Shishim’s legal battle for citizenship was his arrest of the son of a prominent lawyer. The arrested man had claimed that Shishim, who was a California police officer, had no right to arrest an American citizen because he was not and could not become an American citizen (Arab American Historical Foundation n.d.). When Shishim was provided with citizenship because he was considered white, however, a Los Angeles Times article said that “every feature of his dark, swarthy countenance radiate[d] with pleasure and hope” (Gualtieri 2009). According to Beydoun (2015, p. 1), Middle Easterners are hardly perceived as “white” in the American society and find themselves “interlocked between formal classification as white, and de facto recognition as nonwhite”. This is quite clear from the California ruling about Shishim that granted him citizenship and the subsequent article in the LA Times. This discrepancy has obviously led to calls for a change in how MENA Americans are classified, both from within the community—like the ‘Check it Right, You Ain’t White!’ campaign in 2010 (Kahn 2010)—and at the governmental level. In its mid-decade research on race and ethnicity in the 2010s, the U.S. Census Bureau explored two options in its efforts to address the question of how to collect data about residents of MENA descent in the U.S. (Jones 2017). The Bureau’s research considered either the addition of a standalone MENA box or the inclusion of a write-in space for the “White” category for the 2020 census forms. The released questions for the 2020 U.S. census showed that the government opted for the second option and included write-in areas for the “White” category instead of adding a new MENA checkbox (United States Census Bureau 2020).

Ethnographic evidence in Sheydaei (2021) showed that MENA Americans perceived themselves to be physically visible (and distinct from white Americans) based on features such as skin tone, hair type, clothing (mostly for Muslim women), and even demeanor. From an out-group perspective, Maghbouleh et al. (2022) conducted an experimental study where they presented respondents in an online survey with “immigrant” profiles that included information about fictitious immigrants’ home language, ancestry, name, religion, and skin color (presented as a hand with different types of skin pigment) to explore how profiles of MENA immigrants get racially categorized. Maghbouleh et al. found that MENA respondents accepted a wider array of skin tones as MENA, while white respondents considered MENA ethnicity within a narrower band of skin tones. They also found that common MENA names and languages considerably increased rates of racial classification of profiles as MENA (by 5% to 20%) by both groups of respondents. These results confirm other studies that highlight the importance of language as a more reliable index marker for ethnicity than visual cues (Kinzler et al. 2007; Pietraszewski and Schwartz 2014). Sheydaei’s (2021) sociolinguistic interviews with MENA Americans in the Upper Midwest and southern California also showed that while MENA Americans in general do not find their English variety to be distinct from the surrounding mainstream variety, MENA Americans in Dearborn, MI, perceive their English variety to be distinct from the mainstream variety spoken in southeastern Michigan.

The present study is part of a bigger project that combines a bottom-up endogenous community of practice perspective through sociolinguistic interviews and ethnographic fieldwork (e.g., Sheydaei 2023, 2024a, 2024b) with a top-down exogenous speech community perspective through online surveys to investigate the linguistic and physical visibility of MENA Americans. The current paper reports results of the top-down exogenous approach exploring the racial classification of MENA individuals by American respondents by including visual cues from real people with known ancestry to see whether individuals of MENA ancestry are a visible community and are recognized as a distinct racial category based on physical appearance. Then, a perceptual analysis of the English spoken in Dearborn, a “highly visible” (Shryock and Lin 2009, p. 58) Muslim and MENA community in southeastern Michigan, explores whether this particular community is linguistically visible based on their English speech (spoken by L1 English/English dominant speakers of the community, and not spoken as a second language). As such, the present paper seeks to answer the following two questions.

RQ1: Is MENA a visible community in the U.S. based on the index markers of physical appearance and attire?

RQ2: Is the English variety spoken by a highly visible and concentrated MENA American community in Dearborn, MI, recognizable in a local context?

In order to answer the research questions in this paper, two separate online surveys were designed; these surveys used visual and audio cues to see whether people with ethnic ties to MENA are perceived as a visible ethnic community, and whether Dearborn English is a locally recognized (or enregistered as defined by Agha 2003, 2007) variety, respectively. In the next section, I will describe the methodology and results of Study 1.

3. Study 1

In order to answer RQ1 and explore the visibility of people of MENA descent in the U.S. context based on physical appearance, an online Qualtrics survey was designed. This section provides information about the participants and the procedures of Study 1.

3.1. Methodology

An online survey on Qualtrics including pictures of real people with known ancestry was designed for Study 1, to see whether participants in a college context in the U.S. Upper Midwest would recognize MENA as a distinguishable ethnic category based on real people’s physical appearance and attire. Participants in Study 1 were recruited via email invitations sent to all enrolled students in the fall term of 2018. A total of 300 participants took the survey, of whom only 29 participants identified as being from MENA ancestry.

The survey in Study 1 consisted of nine questions (a sample question can be found in the Supplementary Materials); there were four pictures in each question and the participants were asked to categorize the people they saw in the pictures into different ethnic groups. Four boxes titled “Ethnic Group 1” to “Ethnic Group 4” allowed the participants to drag and drop pictures into the different ethnic groups. The participants were asked to drag and drop the pictures into the same group if they thought two or more people belonged to the same ethnic category. Two of the pictures in each question showed faces of people from two different sub-ethnic groups within the MENA region; from the other two pictures, one showed the face of a white person of European descent (white for short), and the other showed the face of a person from a non-European and non-MENA ethnic group (which included African, African American, Asian, Latin American, and Native American) (non-white for short). The pictures in the survey were a combination of (1) pictures selected from reliable news sources including Reuters, CNN, and the BBC, with accurate caption descriptions; and (2) pictures of my friends who agreed to let me use their pictures and made their heritage known to me. A given picture would only occur once in the survey.

3.2. Results

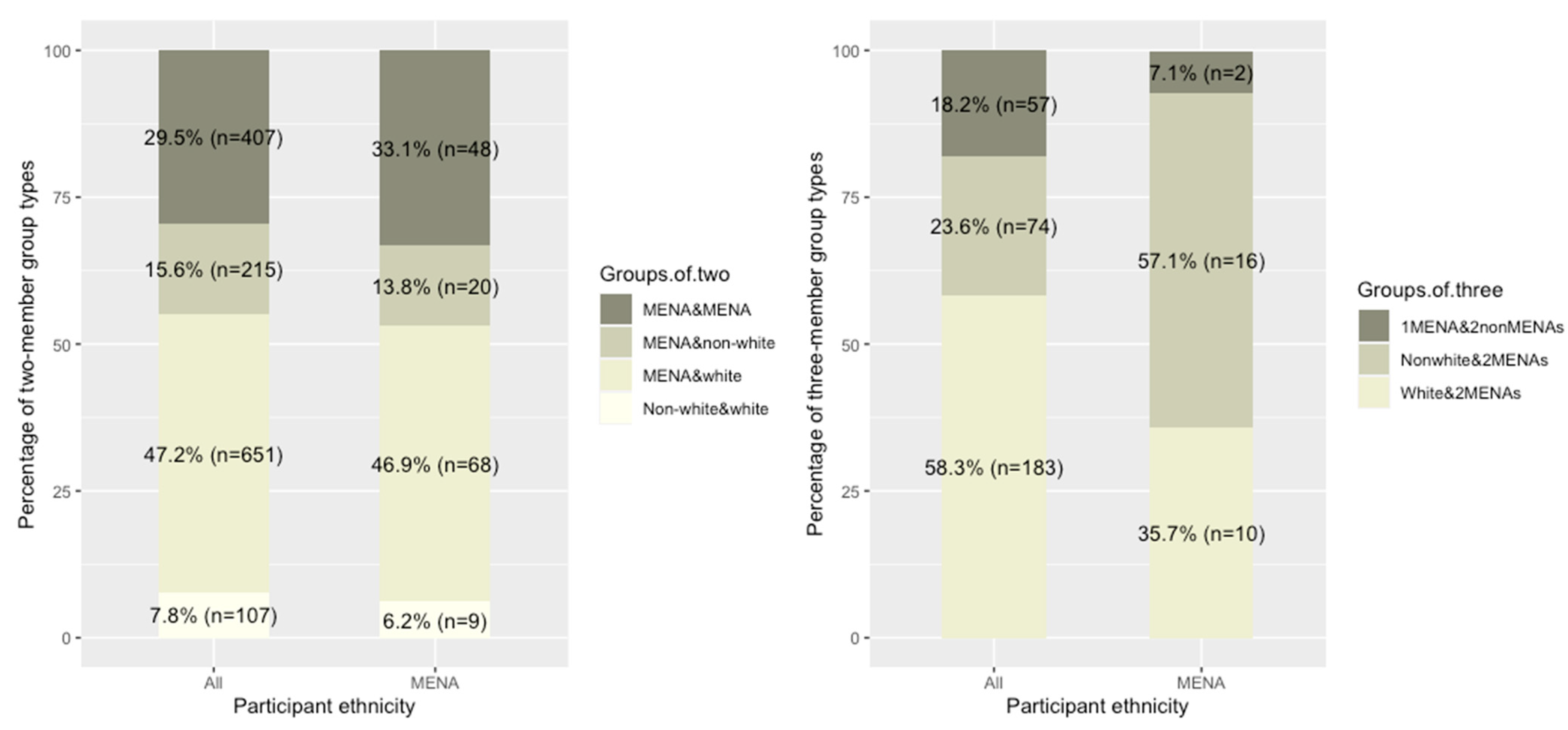

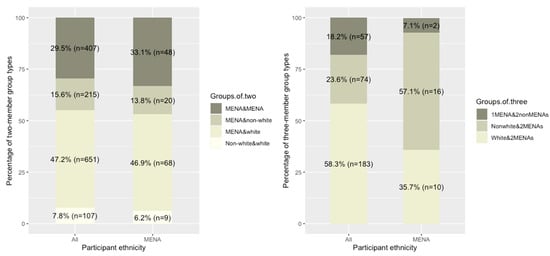

Each question in Study 1’s survey included four pictures and the participants were asked to put the pictures into either the same or different boxes. The four boxes in each question in the survey gave the participants the opportunity to either group each given picture by itself or with other pictures. The majority of groupings were groupings by self (58% for MENA pictures, 83% for non-white pictures, and 62% for white pictures); the same trend was observed for MENA participants in terms of grouping pictures by themselves (53% for MENA pictures, 80% for non-white pictures, and 64% for white pictures). Logistic regression results (full results can be found in the Supplementary Materials) showed that all picture types were significant predictors of grouping a picture by itself (p < 0.01 for all picture types across both participant groups), except MENA pictures for MENA participants, which was not a significant predictor of grouping a picture by itself (p = 0.19). In terms of grouping a picture with other pictures, two- and three-member groups are the most informative in terms of what picture types get grouped together for the purposes of this paper. Figure 1 shows the compositions of two- and three-member groups across participants’ ethnicities.

Figure 1.

Compositions of two- (left) and three-member (right) groups of different picture types in Study 1, formed by both all and MENA participants.

Figure 1 shows that distribution rates are similar across both groups of participants for two-member groups. It also shows that two-member groups of a MENA picture and a white picture are the most frequent by both all (47.2%) and MENA (46.9%) participants. Logistic regression results showed that the MENA picture base is a significant predictor of being grouped with a white picture (p < 0.01) by both groups of participants. In terms of three-member groups, however, the frequency of all participants grouping two non-MENA pictures (the white and non-white pictures in each question) with one MENA picture is more than twice that of MENA participants. Moreover, MENA participants grouped two MENA pictures with a non-white picture at almost the same rate that all participants grouped two MENA pictures with a white picture (57% and 58%, respectively). Logistic regression results show that the all participant group is a significant predictor of three-member groups with two MENA pictures and one white picture (p < 0.01), while the MENA participant group is a significant predictor of three-member groups with two MENA pictures and one non-white picture (p < 0.01).

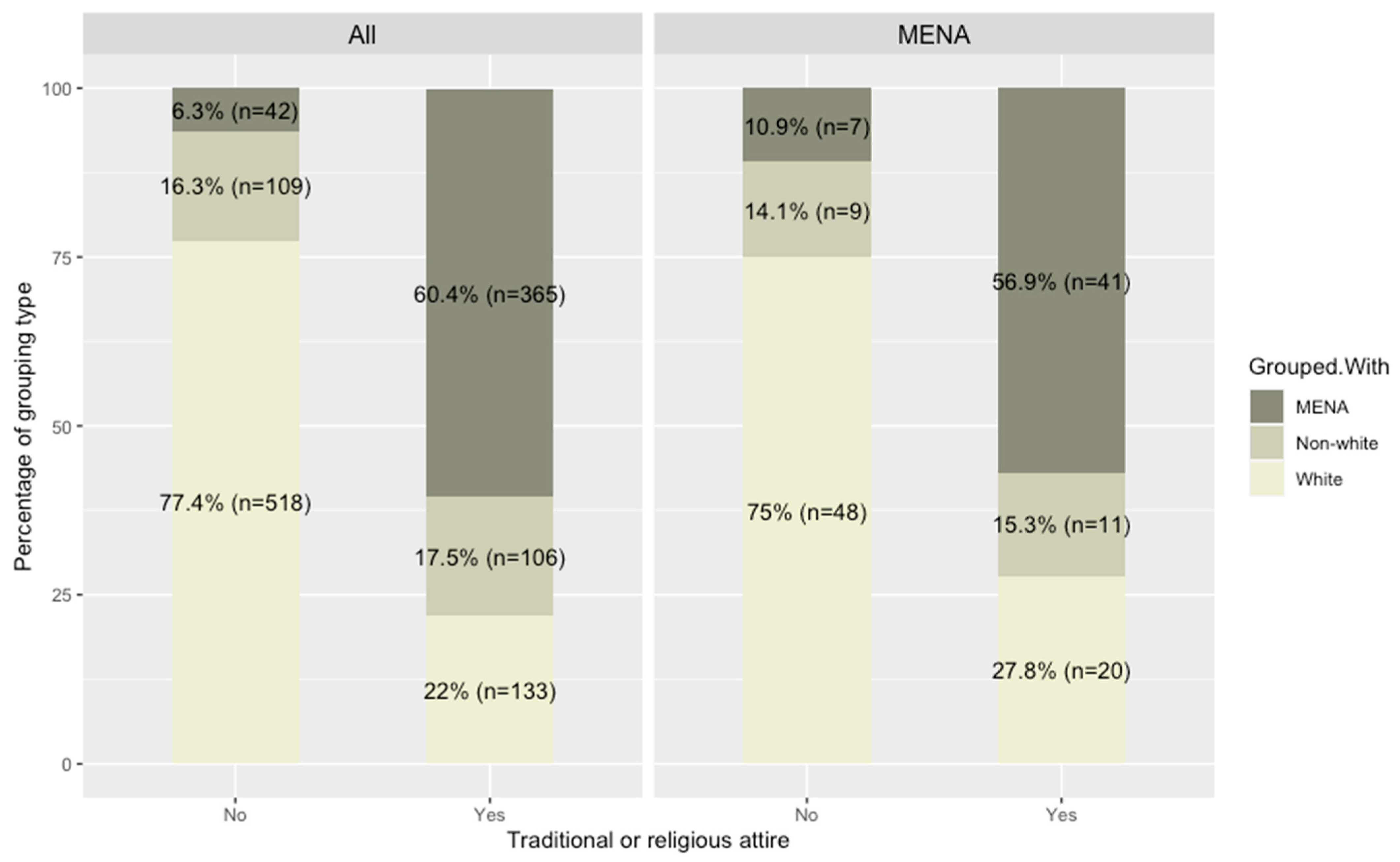

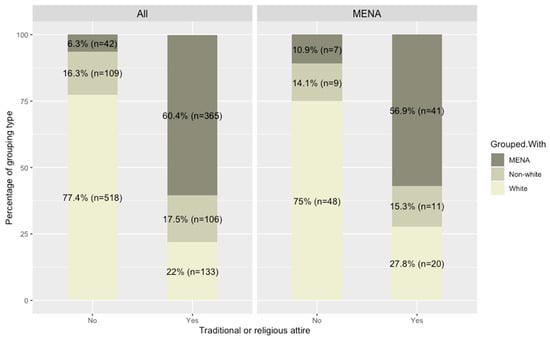

Of the eighteen MENA pictures used in Study 1’s survey, nine (five women and four men) included traditionally or religiously affiliated attire (such as the Islamic headcover, the traditional Kurdish outfit, or the Arabic thawb); therefore, to see whether traditional attire influences the grouping of a MENA picture with another MENA picture, MENA pictures with and without traditional attire in two-member groups are separated and presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of groupings of MENA picture types, with and without traditionally affiliated attire, with other pictures in two-member groups by all participants (left) and MENA participants only (right).

Figure 2 and logistic regression results show that when a MENA picture includes traditionally or religiously affiliated attire, it is a significant predictor of being grouped with another MENA picture (p < 0.01) for both groups of participants, while a lack of traditional attire is a significant predictor of not being grouped with another MENA picture (p < 0.01).

To summarize, the results from Study 1 show that in two-member groups, grouping a MENA picture with a white picture was the most frequent by both groups of participants, even though there were two MENA pictures in each given question, and two-member groups with two MENA pictures were expected to be more frequent. However, traditionally or religiously affiliated attire was a significant predictor of grouping a MENA picture with another MENA picture. This finding highlights the importance of attire as an ethnic marker for individuals of MENA descent. Results from three-member groups also showed that MENA pictures were grouped with a white picture more frequently than with a non-white picture. However, MENA participants tended to group two MENA pictures with a non-white picture more frequently than with a white picture. In summary, while the findings so far—especially the results from the two-member groups—show that MENA ancestry could be ambiguous in terms of ethnic classification (mostly confused with white), attire could be a strong surface pointer in this regard; additionally, MENA participants tended to group MENA pictures with non-white pictures at a significantly higher rate. These findings are in line with MENA Americans’ commentary regarding their ethnic visibility in ethnographic interviews (Sheydaei 2021). In Sheydaei (2021), MENA Americans in the Upper Midwest were asked questions about their physical and linguistic visibility. Regardless of specific locality, MENA Americans mostly believed that they could distinguish individuals of MENA descent based on their physical appearance features including skin tone, hair type, facial hair, and dress. However, only MENA Americans in Dearborn, MI, said they felt they were linguistically visible. Linguistic features that Dearborners identified as specific to their community included certain Arabic words in their English speech (such as allah “God” words, like wallah “[I] swear to God” or yallah “come on be quick”), English words adopted and used with specific meanings local to Dearborn (such as hawk “an Arab male person in Dearborn” or boater “a recent immigrant with a foreign accent”), and certain phonological features. In terms of phonological features, Dearborn speakers described the variety as sounding “deeper”, “gruffy”, and “throaty”. As such, in order to see whether Dearborn is a linguistically visible community and whether the English variety spoken in Dearborn is locally recognized, Study 2 was designed.

4. Study 2

In order to answer RQ2 and explore listeners’ recognition of the English variety spoken in Dearborn, MI, another online survey on Qualtrics was designed. This survey had two identical but separate versions: one including only female voices, and another including only male voices.

4.1. Methodology

A two-section online survey including audio recordings and an interactive map was designed on Qualtrics. Audio recordings in the survey included the same sentence read by 10 different speakers (5 male and 5 female). In each version of the survey, two speakers were from Dearborn, one speaker was a Black speaker from southeastern Michigan, one speaker was a white speaker from southeastern Michigan, and another speaker was a non-native speaker of English with an Arabic accent (the male speaker was from Tunisia, and the female speaker was from Syria). The sentence in the audio recordings was taken out of a reading passage read by the speakers: “He poured it into a tin cup but when he put it up to his lips, he spilled it on his hand; his hand puffed up and hurt a lot”. Participants in Study 2 were recruited via email invitations sent to all enrolled students in the fall term of 2021. 410 listeners took the survey with the female voices, and 391 listeners took the survey with the male voices. Table 1 shows the number of participants in each version of the survey. Participants were asked whether they had ever lived in southeastern Michigan and if yes, for how long; Table 1 reflects that information as well.

Table 1.

Number of participants in Study 2 across the two versions of the survey, subdivided by southeastern Michigan residency backgrounds.

In Section 1 of the survey, participants listened to all 5 recordings and put them in the same group if they sounded similar to each other based on the accent (a sample question can be found in the Supplementary Materials). In Section 2 of the survey, only participants who indicated they had lived in southeastern Michigan listened to the two Dearborn voices, the Black voice, and the white voice in 4 different questions, then selected an urban area on a southeastern Michigan map indicating where they thought the person whose voice they heard was from (a sample question can be found in the Supplementary Materials).

4.2. Results

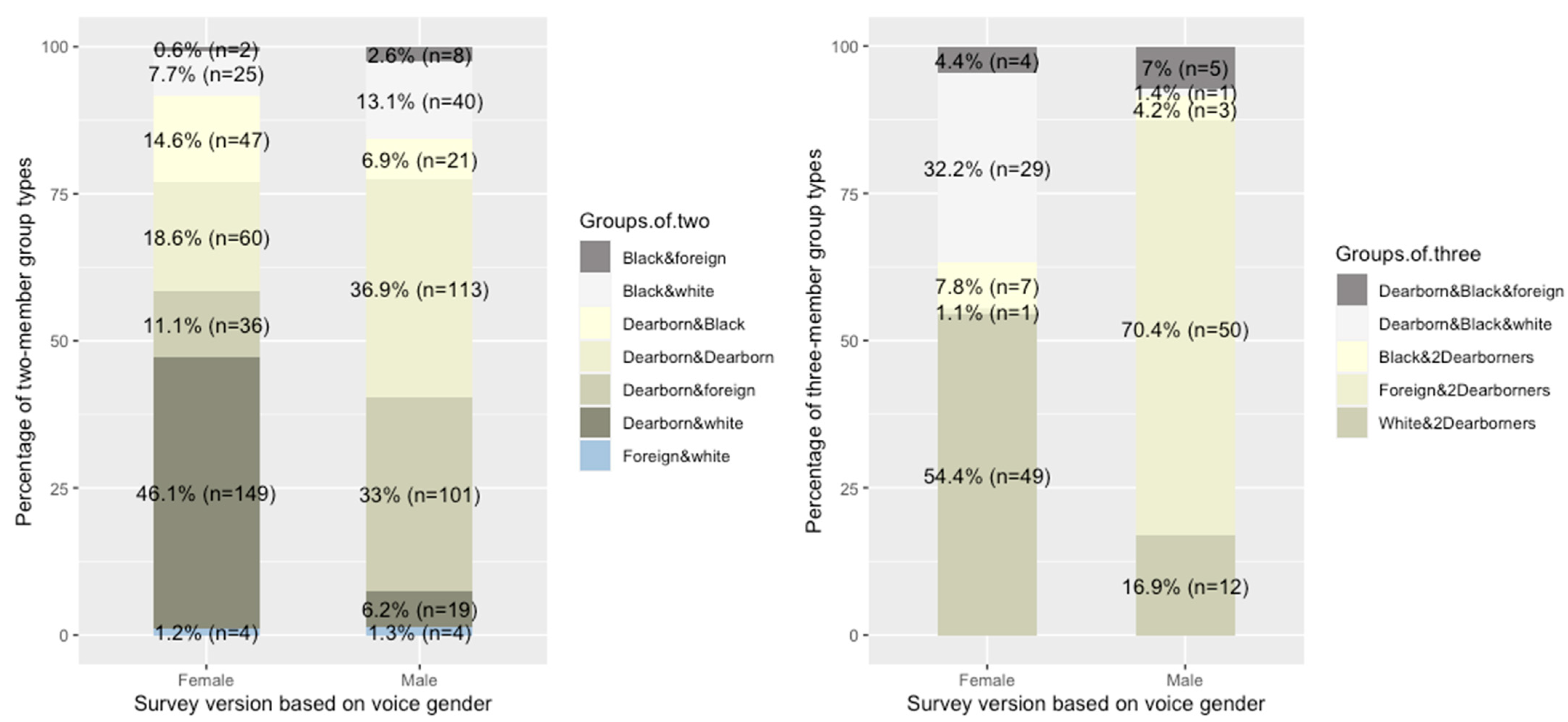

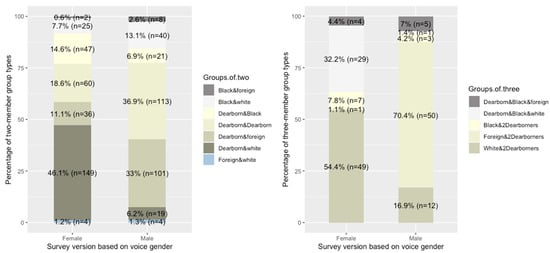

Similar to Study 1, we start the analysis of the results by looking at broad grouping patterns to see what voice type gets grouped by itself most frequently. In the female-voiced version of the survey, the least frequent groupings by self were done for the white and Dearborn voices (34.3% and 36%, respectively), while the foreign-accented voice was grouped by itself most frequently (88.1%) followed by the Black voice (68.9%). In the male-voiced version, however, while the Dearborn voices reserved almost the same proportion of being grouped by themselves (35.2%), the white voice was grouped by itself at a much higher rate (80.6%, up from its female counterpart by 45%), followed by the Black voice (79.5%, up from its female counterpart by 9%), and the foreign-accented voice (56.5%, down from its female counterpart by 32%). Logistic regression results (full results can be found in the Supplementary Materials) showed that in the female-voiced version of the survey, Dearborn and white voices were significant predictors for a voice to be grouped with other voice types (p < 0.01 for both), whereas in the male-voiced version, only Dearborn voices were significant predictors for a voice to be grouped with others (p < 0.01). These observations suggest that female Dearborners could be getting grouped with each other and the white voice more frequently, while male Dearborners could be getting grouped with each other at a higher rate. To explore this pattern, we will look at two-member and three-member groups (visualized in Figure 3) next.

Figure 3.

Compositions of two- (left) and three-member (right) groups of different voice types in Study 2’s Section 1.

Figure 3 shows that when the voice is a female voice, the most frequent two-member group is that of a Dearborn voice and a white voice (46.1%); however, in the male-voiced survey, the most frequent group is the two Dearborn voices together (36.9%), followed by a Dearborner and the foreign-accented voice (33%). Logistic regression results also showed that a Dearborn female voice was a significant predictor of being grouped with the white voice (p < 0.01); however, a male Dearborn voice was a significant predictor of being grouped with either the other Dearborn voice or the foreign-accented voice (p < 0.01 and p < 0.4, respectively). The three-member groups in Figure 3 illustrate the same pattern: the most frequent group in the female-voiced version of the survey is the two female Dearborn voices and the white voice, while in the male-voiced version, the two Dearborn voices and the foreign-accented voice are grouped together most frequently. Logistic regression results show that the female-voiced version of the survey is a significant predictor of three-member groups with two Dearborn speakers and the white speaker (p < 0.01), while the male-voiced version of the survey is a significant predictor of three-member groups with two Dearborn speakers and the Arabic-accented speaker (p < 0.01).

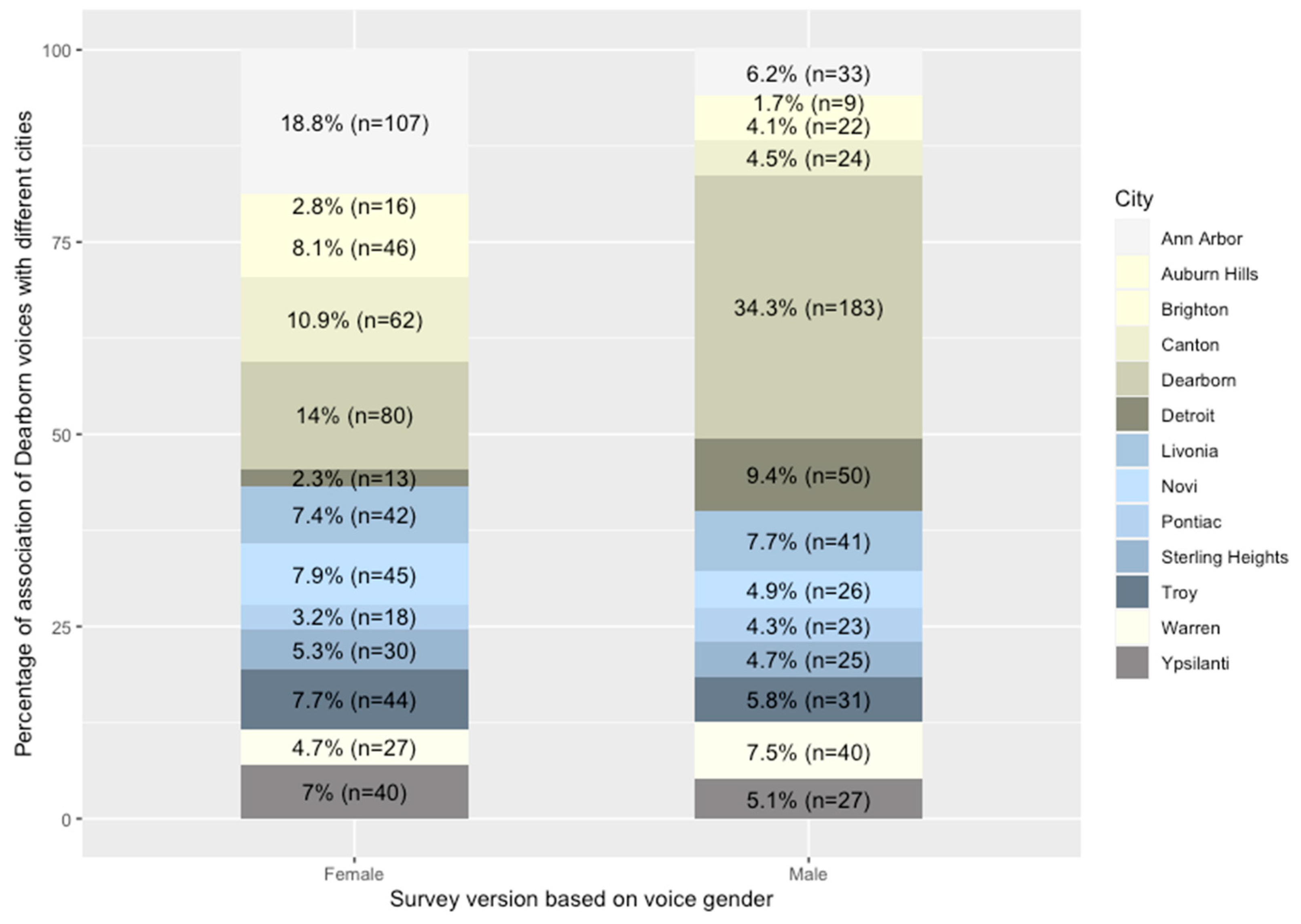

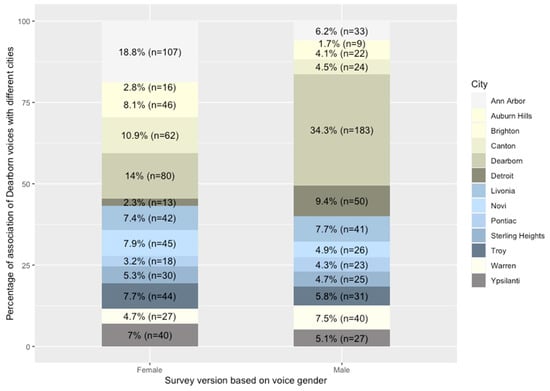

So far, the results show that male Dearborners get grouped with each other more frequently than female Dearborners, and are therefore more linguistically visible. Results from Section 2 of the survey in Study 2 can show us whether Dearborn English gets associated with the locality of Dearborn on a map too. Figure 4 shows the rates of associations between Dearborn voices and different cities on the southeastern Michigan map in Study 2’s survey across both survey versions.

Figure 4.

Association of Dearborn voices with different cities in southeastern Michigan across both survey versions.

Figure 4 clearly shows that male Dearborners get associated with Dearborn most frequently (34.3%), followed by Detroit (9.4%). Female Dearborners, however, get associated with Ann Arbor most frequently (18.8%), followed by Dearborn (14%), and rarely get associated with Detroit (2.3%). Logistic regression results also showed that male Dearborn voices are significant predictors of being associated with the city of Dearborn (p < 0.01). In summary, the results from Study 2 show that Dearborn English is a recognizable variety in the local context of southeastern Michigan, with masculinity associations.

5. Discussion

Within the statistical race (Prewitt 2013) categories of the U.S. census, people of Middle Eastern or North African descent are classified under the racial category white. However, research in the fields of both genomic variation and social sciences shows that people of MENA descent can be categorized differently than white. In their analysis of genomic variation among different populations, Li et al. (2008) showed that the ancestral representation of their Middle Eastern population included components from different continental regions including Europe, Africa, Central and South Asia, and the Middle East itself. The diversity of this ancestral representation is reflected both in anthropological research in the U.S. and in MENA Americans’ sense of social belonging. For example, Shryock and Lin (2009) divided the Middle Eastern community in southeastern Michigan into two zones based on certain cultural pointers to ancestry or ethnicity such as physical appearance, belief system, and dress (all three are cultural surface pointers within Nash’s (1989) model of the core elements of ethnicity). Similarly, research in social sciences shows that MENA Americans are “interlocked between formal classification as white, and de facto recognition as nonwhite” (Beydoun 2015, p. 1). My own ethnographic work (Sheydaei 2021) with MENA Americans shows that from a bottom-up perspective, MENA Americans consider themselves to be physically visible and quite distinct from white people. Physical features that MENA Americans mentioned would make them noticeable included skin color, darker undertones, eyebrows, eye color, eye shape, hair color, curly hair, hairiness, nose shape, dress, headscarf, the hijab, and even demeanor (Sheydaei 2021, p. 83). Study 1 in the present paper investigated the physical visibility of people of MENA ancestry from a top-down exogenous perspective, and the findings showed that MENA can be an ambiguous ethnic category based solely on physical appearance from the top-down perspective. Two-member groups were the most frequent groups in Study 1 (81% of all the groupings with others) and almost half of those groups had a MENA and a white picture as their members, while less than 30% of all two-member groups had two MENA pictures, despite the fact that there were two MENA pictures in each given question which were expected to be grouped together. In fact, a MENA picture was a significant predictor of being grouped with a white picture. However, as the results showed, traditionally or religiously affiliated attire could be a significant predictor of two MENA pictures being grouped together in a two-member group. As such, attire in Study 1 was a stronger ethnic marker for individuals of MENA ancestry than physical appearance. In Study 2, the strength of accent as an ethnic marker was examined with a focus on Dearborn English.

Dearborn city is adjacent to Detroit in Wayne County, Michigan, and is part of the Detroit metropolitan area. Shryock and Lin (2009) describe two distinct zones of the Arab Detroit community: zone 1—which is mostly Christian and suburban—and zone 2, which is “highly visible”, Muslim, and “predominantly in or near Dearborn and Detroit” (p. 58). Ethnographic evidence comparing the sense of visibility of different MENA American communities in the U.S. Upper Midwest shows that only Dearborners feel like they are linguistically noticeable (Sheydaei 2021). Dearborners describe their English variety in terms of its specific lexicon (both from Arabic, such as allah words, and English words such as boater—“a newly arrived immigrant”—or hawk, “an Arab male person in Dearborn”) and its phonological features (sounding “deeper”, “gruffy”, and “throaty”), as well as it being used more by male Dearborners. Sheydaei (2024a) conducted a sociophonetic analysis of Dearborners’ speech and listed some of the features of Dearborn English, such as higher rates of word-final /t/ glottalization; converging VOTs for the lenis and fortis members of bilabial and velar stop sets; and a vowel pattern not consistent with the stereotypical or emerging local patterns. Based on ethnographic evidence, in Sheydaei (2024a), I argued that Dearborn English is an ethnolinguistic repertoire—borrowing the term from the literature on Jewish English in the U.S. (e.g., Benor 2010; Burdin 2020)—rather than an ethnolect, which means Dearborners exhibit agency in their use of Dearborn English features as ethno-local markers with some knowledge about their social meanings. The following comments made by Dearborners during my ethnographic fieldwork (see Sheydaei 2024a, 2024b for a detailed description of the methodology) make it very clear that Dearborn English is an ethnolinguistic repertoire with certain social meanings for Dearborners.

“I think the Dearborn accent is very is like, very obvious”—Speaker DB06

“It’s kind of like a different culture, cultural type of language”—Speaker DB23

“it’s more commonly seen in men, but I’ve seen lots of women that talk just like it too”—Speaker DB18

“I’ve seen like a lot of, like, friends of mine who have been called out on it um like, mine isn’t like, as severe as, like, other people, but like, I, for example, like a friend of mine, he was interviewed by this one, like random TikTok guy, like who goes around interviewing people across campus. And I’ve seen like the comments section. People are like, uh, just like kind of clowning on them, just like seeing like straight at Dearborn and stuff like that. Um, and it’s like hundreds of people, like with the same exact thing. So it’s, it’s definitely clear to some people, but like, yeah me not, not too much.”—Speaker DB27

These comments show that not only Dearborners, but also non-Dearborners in southeastern Michigan recognize the Dearborn accent (e.g., Speaker DB27 mentions hundreds of comments on a TikTok video from people who point out the Dearborn accent). Additionally, these comments show that Dearborn English is a variety that is not spoken by all Dearborners, but is mostly a “cultural language” that residents code-switch to in certain situations.

Study 2 in the current paper supplements this bottom-up ethnographic evidence about the recognition of Dearborn English on a local level by exploring the local enregisterment (Agha 2003, 2007) of Dearborn English from a top-down perspective. The results of the online survey in Study 2 showed that a male Dearborn voice was a significant predictor of getting grouped with another Dearborn voice in two-member groups (81% of all groups with others in the male-voiced survey, and 76% of all groups with others in the female-voiced version) and of being associated with the specific locality of Dearborn. In other words, Study 2 showed that male speakers from Dearborn are mostly associated with their respective locality, which means that Dearborn English could not only be a locally enregistered variety, but also an ethno-local marker. The perceptual associations of Dearborn English with masculinity are in line with the ethnographic evidence reported above, as well as previous anthropological research on diasporic communities that shows immigrant communities could be fragmented along certain lines such as gender or religiosity (e.g., Khosravi 2009, 2018). Specifically focusing on the Iranian immigrant community in Sweden, Khosravi (2009) showed that male members of the community could be more isolated, and as a result more visible and “an object of the gaze of others” (p. 609). Such higher visibility could translate into more noticeable linguistic behaviors from a sociolinguistic perspective as our evidence here suggests. However, as evidenced by Speaker DB18’s comment above, there are still “lots of women” in Dearborn that use features of Dearborn English in their speech. In fact, my own analysis of female Dearborners’ speech showed that ethnic visibility affects their linguistic choices with reference to Dearborn English features: my findings in Sheydaei (2024c) revealed that while all female Dearborners showed similarly high rates of /t/ glottalization in their speech (a prominent feature of Dearborn English), hijab-wearing Dearborners’ speech featured stop VOT distributions and a vowel patterning more strongly aligned with the features of Dearborn English. In summary, the results of Study 2 and the ethnographic evidence reported here together show that while Dearborn English is a recognizable variety in southeastern Michigan, it is an ethnolinguistic repertoire. This means that Dearborn residents, and by extension MENA Americans in other places, can use certain ethno-local markers of Dearborn English to project their ethno-local identity and be more visible (linguistically). These stylistic choices would happen at the intersection with out-group language attitudes towards Dearborn English and MENA Americans in general.

As discussed above, one necessary initial condition for studying out-group language attitudes towards a particular variety and in-group variation in relation to the variety is the enregisterment of the given variety. The noticeability or visibility of a community is possible only if certain markers indicate the existence of any given community. Once a certain variety becomes recognizable with its indexical features, in-group members could be consciously sending linguistic markers in response to out-group evaluative judgments and attitudes. Therefore, with the evidence reported in this study regarding the strength of attire and accent as ethnic markers for MENA Americans and ethno-local markers for MENA Americans in Dearborn, future research can document out-group language attitudes towards Dearborn English on its own, as well as at the intersection with visual cues including attire. As such, future research can explore how listeners associate Dearborn English with certain phenotypical features, sartorial choices, and personality types. As mentioned in the Introduction section, the first step in exploring the social consequences of evaluative judgments towards language varieties is to document such language attitudes. No such work has been done with Dearborn English, to my knowledge. Given the association of Dearborn English with the geographic locality of Dearborn, reported here, and the strength of attire as an ethnic marker for MENA Americans, it is expected that Dearborn English will be evaluated as strongly connected to Islamic sartorial choices and darker phenotypical traits—features closely tied to “the perceptions and stereotypes of Muslim “culture”” (Durrani 2018, p. 45).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genealogy8020041/s1, Figure S1: Sample question from Study 1’s survey, Figure S2: Sample question from Section 1 of the survey in Study 2, Figure S3: Sample question from Section 2 of the survey in Study 2, Table S1: Logistic regression results for different grouping patterns within Study 1; Table S2: Logistic regression results for different grouping patterns within Study 2.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Wisconsin-Madison (protocol code 2017-1203 on 2 November 2017) and the University of Michigan (protocol code HUM00205886 on 26 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Tom Purnell for his incredibly generous help with this project. I would also like to thank Jacee Cho, Eric Raimy, Joe Salmons, Pam Beddor, Robin Queen, multiple anonymous reviewers, and attendees at the 2023 annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Finally, I am most thankful to all the participants in this project. All errors are of course my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Agha, Asif. 2003. The social life of cultural value. Language and Communication 23: 231–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, Asif. 2007. Language and Social Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, Samy. 2016. Who’s afraid of the transracial subject? In Raciolinguistics: How Language Shapes Our Ideas about Race. Edited by Samy Alim, John R. Rickford and Arnetha F. Ball. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Arab American Historical Foundation. n.d. Department of Justice Affirms in 1909 Whether Syrians, Turks, and Arabs Are of White or Yellow Race. Available online: http://www.arabamericanhistory.org/archives/dept-of-justice-affirms-arab-race-in-1909/ (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Benor, Sarah Bunin. 2010. Ethnolinguistic repertoire: Shifting the analytic focus in language and ethnicity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 14: 159–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beydoun, Khaled A. 2015. A demographic threat? Proposed reclassification of Arab Americans on the 2020 Census. Michigan Law Review Online 114: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bozoglan, Hilal, and Duygu Gok. 2016. Effects of mobile-assisted dialect awareness training on the dialect attitudes of prospective English language teachers. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38: 772–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdin, Rachel Steindel. 2020. The perception of macro-rhythm in Jewish English intonation. American Speech 95: 263–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calamai, Silvia, and Fabio Ardolino. 2020. Italian with an accent: The case of “Chinese Italian” in Tuscan high schools. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 39: 132–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartmill, Matt. 1998. The status of the race concept in physical anthropology. American Anthropologist 100: 651–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupland, Nikolas, and Hywel Bishop. 2007. Ideologized values for British accents. Journal of Sociolinguistics 11: 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, Jennifer. 2016. Contested Southernness: The Linguistic Production and Perception of Identities in the Borderlands. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dragojevic, Marko, Fabio Fasoli, Jennifer Cramer, and Tamara Rakić. 2021. Toward a century of language attitudes research: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 40: 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragojevic, Marko, Howard Giles, Anna-Carrie Beck, and Nicholas T. Tatum. 2017. The fluency principle: Why foreign accent strength negatively biases language attitudes. Communication Monographs 84: 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, Mariam. 2018. Communicating and contesting Islamophobia. In Language and Social Justice in Practice. Edited by Netta Avineri, Laura R. Graham, Eric J. Johnson, Robin Conley Riner and Jonathan Rosa. Boca Raton: Routledge, pp. 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Marcus. 2010. The biology of ancestry: DNA, genomic variation, and race. In Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century. Edited by Hazel Markus and Paula Moya. New York: W.W. Norton, pp. 136–59. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Bernadette Watson. 2013. The Social Meanings of Language, Dialect, and Accent: International Perspectives on Speech Styles. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Patricia Johnson. 1987. Ethnolinguistic identity theory: A social psychological approach to language maintenance. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 68: 69–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, Howard, and Richard Y. Bourhis. 1975. Linguistic assimilation: West Indians in Cardiff. Language Sciences 38: 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Richard Y. Bourhis. 1976. Voice and racial categorization in Britain. Communication Monographs 43: 108–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluszek, Agata, and John F. Dovidio. 2010. The way they speak: A social psychological perspective on the stigma of nonnative accents in communication. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 214–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, Sarah. 2009. Syrian immigrants and debates on racial belonging in Los Angeles, 1875–1945. Syrian Studies Association 15. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=c-gkLg0AAAAJ&citation_for_view=c-gkLg0AAAAJ:Tyk-4Ss8FVUC (accessed on 21 July 2019).

- Hoffman, Michol F., and James A. Walker. 2010. Ethnolects and the city: Ethnic orientation and linguistic variation in Toronto English. Language Variation and Change 22: 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Nicholas A. 2017. Update on the US Census Bureau’s Race and Ethnic Research for the 2020 Census; Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

- Kahn, Carrie. 2010. Arab-American Census Activists Say ‘Check It Right’. NPR.org. March 29. Available online: https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=125317502 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Khoshneviss, Hadi. 2019. The inferior white: Politics and practices of racialization of people from the Middle East in the US. Ethnicities 19: 117–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, Shahram. 2009. Displaced masculinity: Gender and ethnicity among Iranian men in Sweden. Iranian Studies 42: 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, Shahram. 2018. A fragmented diaspora: Iranians in Sweden. Nordic Journal of Migration Research 8: 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzler, Katherine D., Emmanuel Dupoux, and Elizabeth S. Spelke. 2007. The native language of social cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 104: 12577–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Barbara. 2010. Which differences make a difference? Race, DNA, and health. In Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century. Edited by Hazel Markus and Paula Moya. New York: W.W. Norton, pp. 160–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin, Richard. 1991. Human Diversity. New York: Scientific American Library. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin, Richard. 1996. Biology as Ideology: The Doctrine of DNA. New York: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jun Z., Devin M. Absher, Hua Tang, Audrey M. Southwick, Amanda M. Casto, Sohini Ramachandran, Howard M. Cann, Gregory S. Barsh, Marcus W. Feldman, Luigi L. Cavalli-Sforza, and et al. 2008. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science 319: 1100–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, Stephanie. 2005. Who speaks “broken English”? US undergraduates’ perceptions of non-native English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 15: 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlefield, Alice, Leonard Lieberman, and Larry T. Reynolds. 1982. Redefining race: The potential demise of a concept in physical anthropology. Current Anthropology 23: 641–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghbouleh, Neda. 2017. The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maghbouleh, Neda, Ariela Schachter, and René D. Flores. 2022. Middle Eastern and North African Americans may not be perceived, nor perceive themselves, to be White. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119: e2117940119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvasti, Amir, and Karyn D. McKinney. 2004. Middle Eastern Lives in America. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Manning. 1989. The Cauldron of Ethnicity in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszewski, David, and Alex Schwartz. 2014. Evidence that accent is a dedicated dimension of social categorization, not a byproduct of coalitional categorization. Evolution and Human Behavior 35: 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, Dennis R. 1998. They speak really bad English down south and in New York City. In Language Myths. Edited by Laurie Bauer and Peter Trudgill. London: Penguin, pp. 139–49. [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt, Kenneth. 2013. What Is Your Race?: The Census and Our Flawed Efforts to Classify AMERICANS. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rakić, Tamara, Melanie C. Steffens, and Amélie Mummendey. 2011. Blinded by the accent! The minor role of looks in ethnic categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakić, Tamara, Melanie C. Steffens, and Atena Sazegar. 2020. Do people remember what is prototypical? The Role of accent–religion intersectionality for individual and category memory. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 39: 476–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessel, Janin, Christiane Schoel, Renate Zimmermann, and Dagmar Stahlberg. 2019. Shedding new light on the evaluation of accented speakers: Basic mechanisms behind nonnative listeners’ evaluations of nonnative accented job candidates. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 38: 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Donald L. 1992. Nonlanguage factors affecting undergraduates’ judgments of nonnative English-speaking teaching assistants. Research in Higher Education 33: 511–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheydaei, Iman. 2021. Local and Ethnic Identities: MENA Americans’ Linguistic Behavior and Ethnic Rootedness. Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sheydaei, Iman. 2023. The Low-Back-Merger Shift: Evidence from MENA Americans in the Upper Midwest and southern California. English Today. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheydaei, Iman. 2024a. Dearborn English: An ethnolinguistic repertoire for MENA Americans. Linguistic Geography 12. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Sheydaei, Iman. 2024b. Ethnic rootedness and social affiliations at the interface with linguistic performativity: Evidence from Americans of Southwest Asian or North African Descent. Languages 9: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheydaei, Iman. 2024c. Ethnic visibility and ethnolinguistic repertoires: Dearborn English and the hijab. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 9: 5669, Forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrikant, Natasha, Howard Giles, and Daniel Angus. 2022. Language and Social Psychology approaches to race, racism, and social justice: Analyzing the past and revealing ways forward. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 41: 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shryock, Andrew, and Ann Chih Lin. 2009. Arab American identities in question. In Citizenship and Crisis: Arab Detroit after 9/11. Edited by Wayne Baker, Sally Howell, Amaney Jamal, Ann Chih Lin, Andrew Shryock, Ronald R. Stockton and Mark Tessler. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley, Audrey, and Brian D. Smedley. 2005. Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: Anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American Psychologist 60: 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Census Bureau. 2020. Decennial Census of Population and Housing Questionnaires & Instructions. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/technical-documentation/questionnaires.2020_Census.html#list-tab-1168974309 (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Wolfram, Wolfram, and Natalie Schilling. 2015. American English: Dialects and Variation. Malden: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).