Researching Pre-1808 Polish-Jewish Ancestral Roots: The KUMEC and KRELL Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Polish-Jewish Records

- Rabbinic sources: Rabbinic sources include records and writings produced by Jewish religious leaders, such as rabbis. This category encompasses a wide range of materials, including responsa (answers to legal questions), sermons, and communal records maintained by rabbinic authorities. Rabbinic sources can offer insights into the religious and legal aspects of Jewish life. Family relationships, events, and community dynamics may be documented in responsa and communal records. Rabbinic genealogies, especially those found in works like Otzar Harabanim (Friedman 1975) and several others, can also be valuable for tracing lineages.

- Approbations (Haskamot): Approbations are endorsements or approvals often found at the beginning of a Jewish book, indicating that the work has been reviewed and approved by a reputable authority, such as a rabbi. In addition to providing information about the book’s approval, Haskamot may contain details about the author, the community in which they lived, and sometimes even the names of the author’s family members. Researchers can glean insights into the social and intellectual networks of the time.

- Pinkas HaKehillot: Pinkas HaKehillot is a series of books that document the daily history of Jewish communities in various towns and cities. They provide information about community life, synagogue records, and sometimes lists of residents.

- Jewish cemeteries: Headstones in Jewish cemeteries often contain vital information such as names, birth and death dates, and sometimes even relationships. Headstones may contain symbols, inscriptions, or epitaphs that provide additional information about the deceased, their character, or their relationships. This can provide insights into family connections, religious affiliations, and migration patterns.

- Mohel Books: Mohel books, or circumcision records, document the circumcisions performed by a mohel (ritual circumciser) in a Jewish community. These records often include details such as the names of the child, the parents, and sometimes the date and location of the circumcision. Mohel books can provide valuable information about family relationships, generations, and sometimes even the names of grandparents. These records may offer insights into the religious and communal life of the Jewish population in a specific area.

- Ketubot (Marriage Contracts): Ketubot are Jewish marriage contracts that outline the rights and responsibilities of the husband and wife. These documents often include details about the bride, groom, and their families. Ketubot can be essential for genealogical research as they provide information about the names of the bride and groom, their fathers’ names, and occasionally additional family details. These records are especially helpful for tracing the maternal lines of a family.

- JewishGen: JewishGen is a platform that appeared in 1995 on the internet as a pioneering Jewish genealogy resource. It lists millions of Jewish records, hundreds of translated yizkor (memorial) books, research tools, a family finder, educational classes, historical components, and many other resources.

- Jewish Records Indexing—Poland (JRI-Poland): JRI-Poland is an online database that provides access to a vast collection of Jewish vital records from Poland, including information on births, marriages, and deaths. The database is continually updated and serves as a great resource for researchers looking to trace their Jewish roots in Poland.

- Polish State Archives (PSA): The Polish State Archives hold a variety of records, including vital records, census data, and other documents relevant to genealogical research. Researchers may find information about Jewish ancestors in these archives, particularly in vital records from specific towns and regions with significant Jewish populations.

- The Jewish Historical Institute (JHI) in Warsaw: The JHI in Warsaw is a key institution for researching Jewish history in Poland. It holds a variety of documents, including vital records, synagogue records, and other materials relevant to Jewish genealogy. The JHI is an important resource for researchers looking to explore their Jewish-Polish roots.

- Yizkor Books: Yizkor books are memorial books written by Jewish communities in memory of their towns and residents who perished during the Holocaust. These books often contain historical information, photographs, and personal accounts that can be valuable for genealogical research.

- Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (CAHJP): Located in Jerusalem, CAHJP houses a significant collection of documents related to Jewish history, including materials from Poland. Researchers may find letters, diaries, and other personal documents that can aid in genealogical research.

- Holocaust Records: For those researching Jewish ancestry in Poland during the Holocaust, records from Yad Vashem in Israel and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum can provide information on Holocaust victims and survivors.

3. First Case Study: Two KUMEC Family Clusters in Konskie

3.1. Wyszogrod: Exploring the Earliest Metrical Records

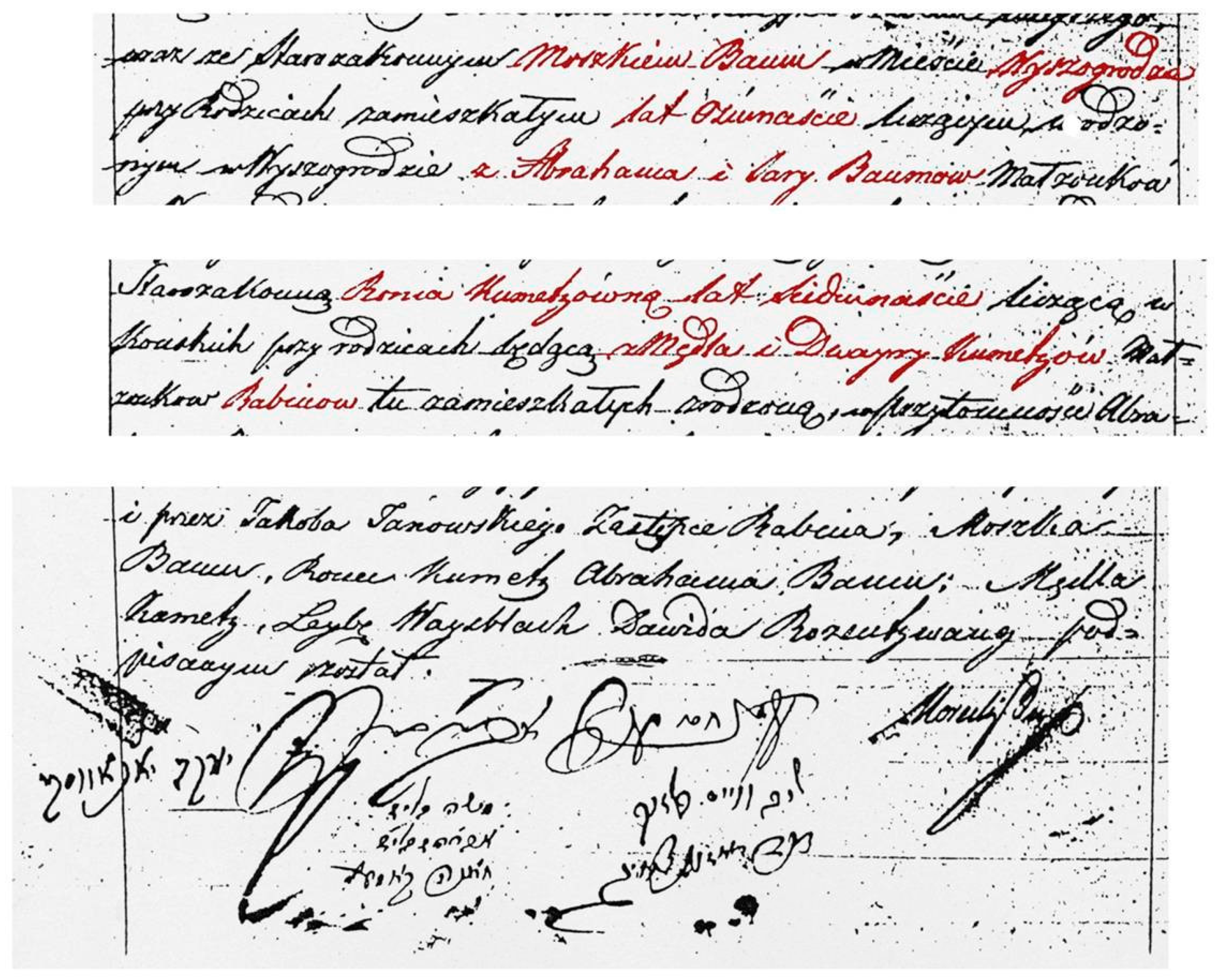

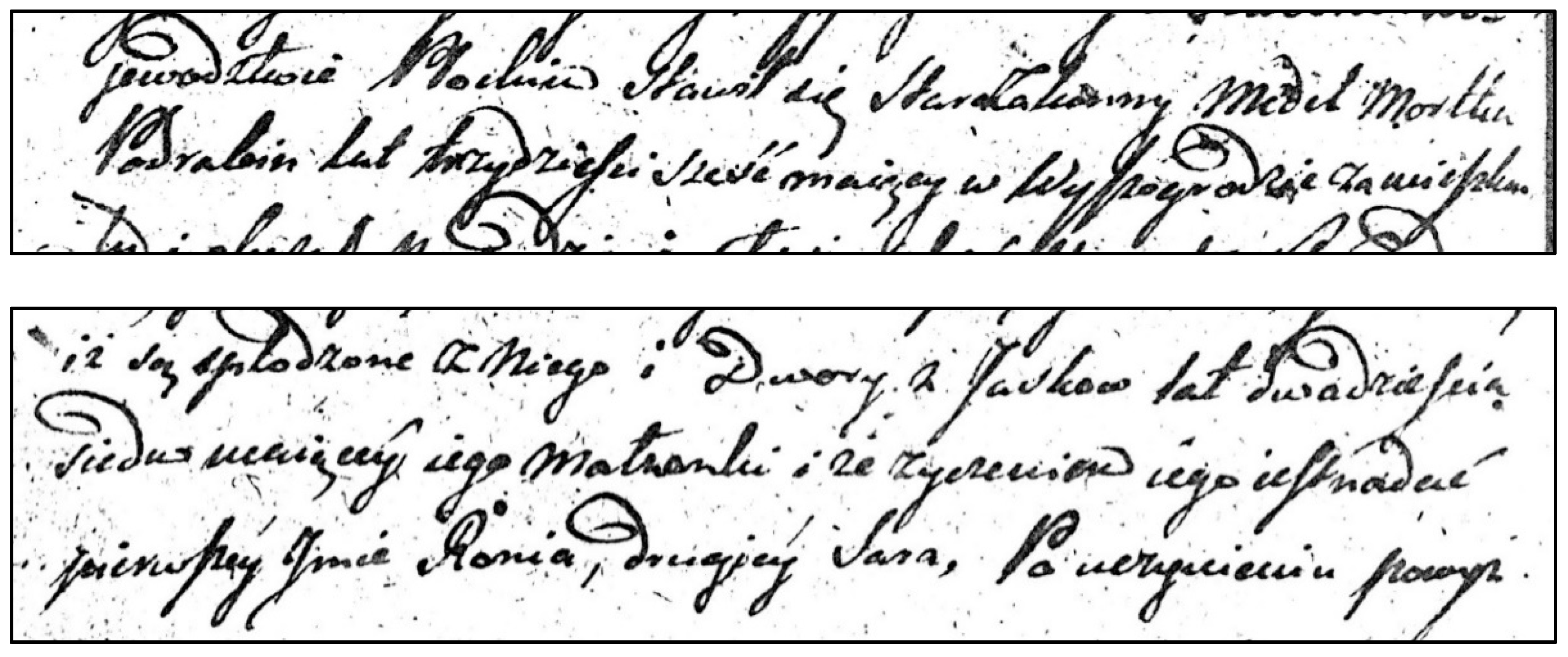

- A somewhat difficult-to-decipher birth record from 1815 was located for Ronia. The document specifies Ronia’s parentage as Mendel Mordka (Mendel, son of Mordka) and Dwojra Josek (Dwojra, daughter of Josek).

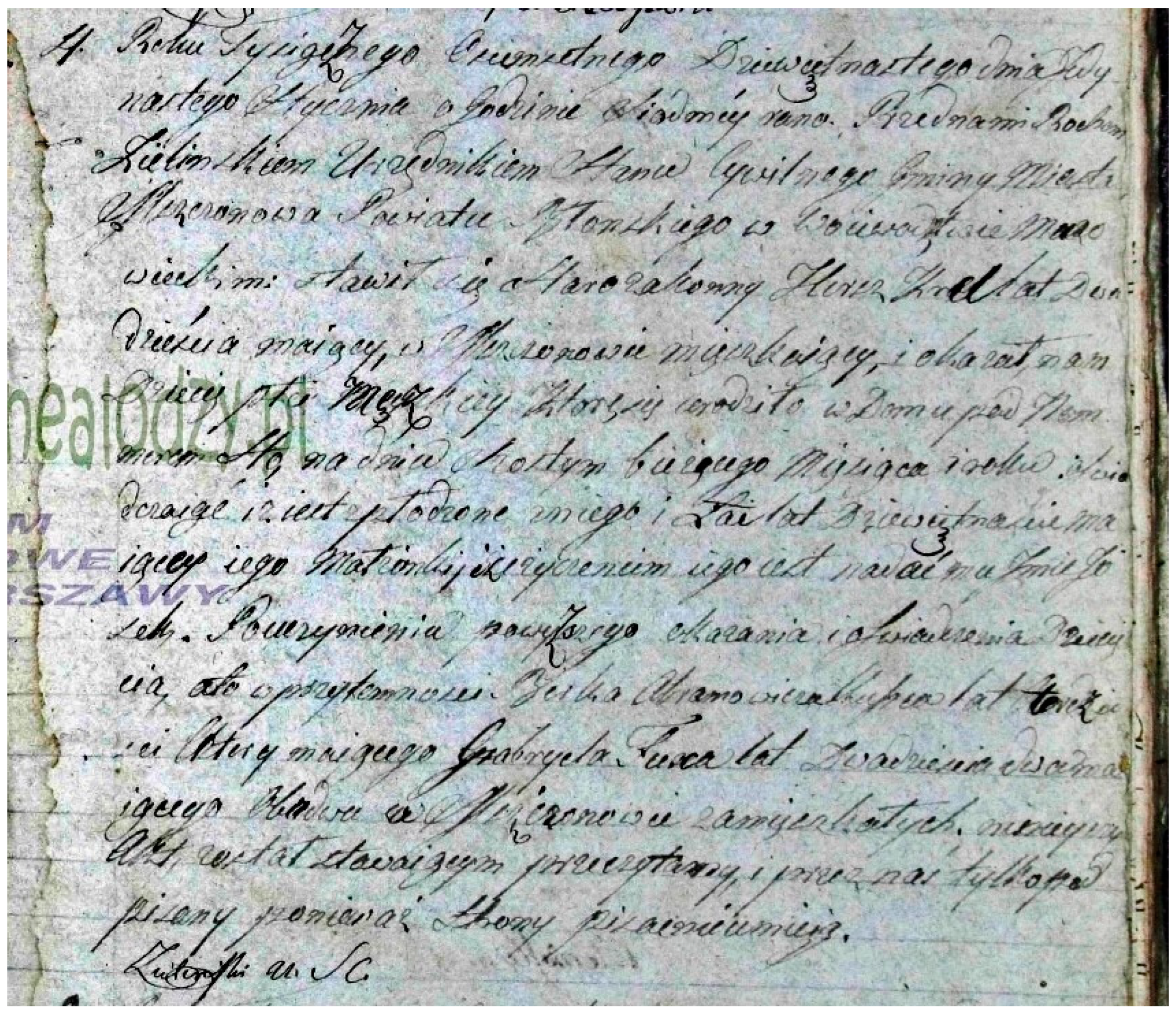

- In 1818, another birth record was discovered, documenting the birth of Ronia, the daughter of Mendel Mordka, who held the title of ‘podrabin’ (Under-Rabbi), and Dwojra Josek (refer to Figure 3). In contrast to the 1815 record, this second document not only confirmed Ronia’s birth but also revealed the presence of her twin sister, Sara. The absence of Sara’s birth information in the 1815 record suggests that the 1818 entry might have served as a substitute or correction for the earlier omission. Interestingly, both Ronia and Sara went on to marry in 1832, in Konskie.

- The marriage record from 1815 documenting the union of Ester Effrem, a sibling of Mendel KUMEC, with a man named Uszer Markus (adding an additional layer of complexity).

- The death record from 1813 of Markus Effrem/Froim, possibly aged 60, husband of Rojza, the daughter of Wolek Effrem. Mendel Markus himself is listed as one of the witnesses, establishing that this Markus (also identified as Mordka/Mortek) was indeed Mendel’s father. This fact was corroborated by Mendel’s 1842 death record, which identified Dwojra as Mendel’s mother. Moreover, there is a chance that Mendel Markus had a sibling named Abram Mordka, who seems to be referenced as a witness in Markus Effrem’s death record, although the text is difficult to decipher).

3.2. Wyszogrod: The Yizkor Book

3.3. Tykocin: The Yizkor Book

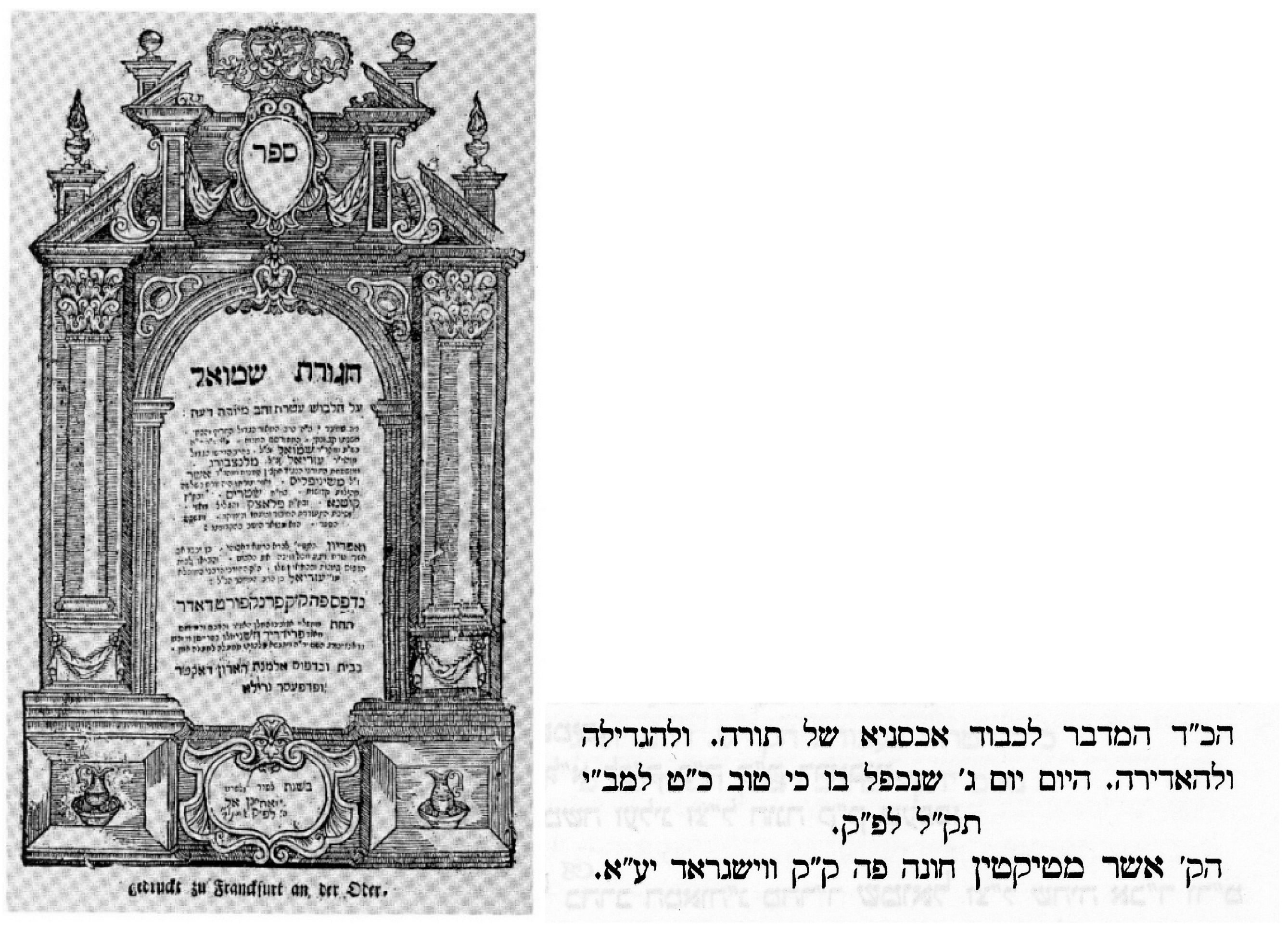

This discovery extended the family tree, tracing its origins to the early 1700s. Genealogy research in rabbinical books was the expected next step.“Asher KUMEC was born in Tykocin in the early 1700s, and served there in 1767 as a Rabbinical Judge (Av Beit Din). Earlier, he had been a pupil of Rabbi Shalom Rokach of Tykocin, and then replaced him upon Rokach’s passing. However, he only served for a year before moving in 1768 to the small community of Wyszogrod where he served as Rabbinical Judge. He gave his Approbation (‘Haskama’, an introduction to a manuscript by an eminent religious personality) to ‘Hagorat Shmuel’ (Shmuel’s Belt), the book of Rabbi Shmuel Ben Azriel from Landsberg, a Rabbi in Plock. (…) Another book, ‘Pnei Arieh’ (‘Arieh’s Face’) written by Rabbi Arieh Leyb KATZ (KAC, or K”C), who was Asher KUMEC’ son-in-law, has an Approbation by Asher KUMEC’ own son, Froim KUMEC”.

3.4. Rabbinical Books

- a.

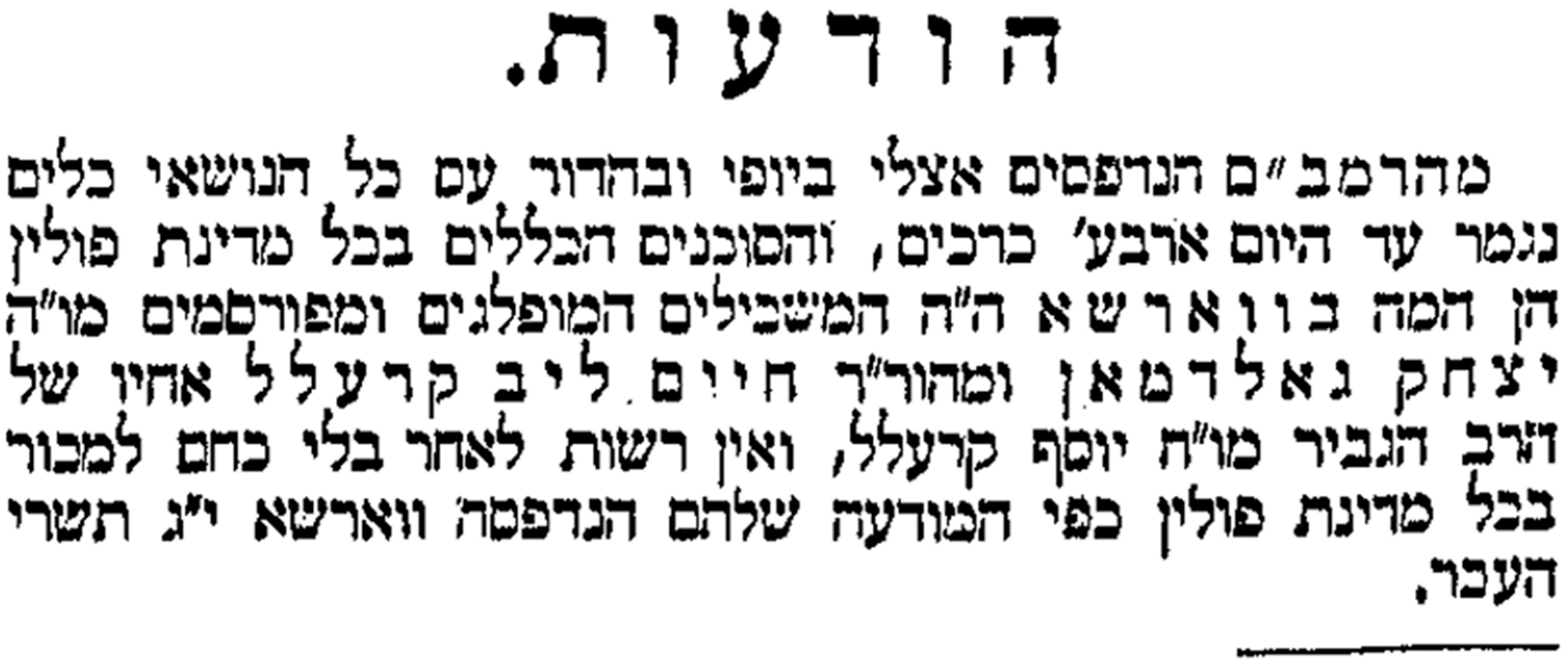

- The 1770 book authored by Rabbi Shmuel Ben Azriel from Landsberg, titled “Hagorat Shmuel” (“Shmuel’s Belt”) (Ben Azriel 1770), a Rabbi in Plock, notably includes an approbation (‘Haskama’) from Rabbi Asher KUMEC. From this, we glean the insight that “due to modesty, Rabbi Asher rarely provided his endorsement for books” (refer to Figure 5).

- b.

- The cover page of the book “Pnei Arieh” (“Arieh’s Face”) (Katz 1787) penned by Rabbi Arieh Leyb KATZ (KAC, or K”C) and published in 1787 in Nowy Dwor, makes reference to the author’s father-in-law, Rabbi Asher KUMEC. Notably, the book contains an approbation provided by Rabbi Efroim KUMEC, Asher KUMEC’s son (refer to Figure 6).

- c.

- The book “Divrei Gdolim” (Michelson 1933) (“Words From the Great Ones”) (Figure 7) includes a biography (pages 6–10) of Rabbi Asher KUMEC encompassing the following key details:

- Natan, the son of Asher KUMEC, passed away in 5581 (1820–1821).

- Efroim, the son of Asher KUMEC, served as a Rabbinical Judge in Wrzesnia.

- A daughter of Asher KUMEC was wedded to Arieh Leyb, the author of “Pnei Arieh”.

- Rabbanit KUMEC, Asher’s wife, passed away on 11 Cheshvan 5531 (30 October 1770).

- d.

- Considering the notable presence of Rabbis in the KUMEC lineage, turning to the authoritative work “Otzar HaRabanim” (Friedman 1975) (“A Treasury of Rabbis”) appeared to be a logical decision. This reference indeed furnished the date of death for Rabbi Asher KUMEC, which occurred on 4 Kislev 5540 (13 November 1779).

- e.

- Additionally, insights from “Pinkas Kahal Tiktin” (Nadav 1996) (“The Minutes Book of the Jewish Community Council of Tykocin”), a remarkably well-preserved and distinctive tome containing records of rabbinical meetings in Tykocin from 1621 to 1806, unveiled the following details concerning Rabbi Asher ben Mordechai and the persistence of the KUMEC surname:1. Page 20:-Rabbi Asher ben Mordechai is noted as the Rabbinical Judge in Tykocin and Wyszogrod.2. Page 28—Item 56, Rosh Hodesh Nisan 5502 (5 April 1742):-Rabbi Asher ben Mordechai is designated to become a ‘Magid (speaker)’ in the congregation.3. Page 37—Item 70, 27 Sivan 5516 (25 June 1756):-Mention of Rabbi Asher ben Mordechai.4. Page 145:-Reference to Mordechai KUMEC.5. Page 148—Item 232, 26 Kislev 5466 (13 December 1705):-“The widow of Mr Mordechai KUMEC” is mentioned.6. Page 151—Item 240, 20 Tamuz 5466 (2 July 1706):-Mention of “Sara the widow of M”hram [Moreinu HaRav Mordechai] KUMEC”.7. Page 602—Item 909, Pesach 5498 (1738):-Mention of Mr Asher ben Mordechai.8. Page 606—Item 918, Pesach 5499 (1739):-Mention of Mr Asher ben Mordechai.9. Page 607—Item 919, 6 Iyar 5499 (14 May 1739) or 6 Iyar 5502 (10 May 1742) (?):-Mention of Mr Asher ben Mordechai.

- f.

- In January 2008, after attending a scientific conference in the USA, I seized the chance to convey my appreciation to Rabbi Dov Weber for his invaluable assistance and guidance in utilizing rabbinical sources for my research. During our conversation about our shared interest in genealogy, Rabbi Weber shared with me a copy of “Avnei Zikaron” (Weber and Rosenstein 1999) (“Stones of Remembrance”), a book he co-authored with Neil Rosenstein in 1999. The book relies on the original manuscript titled the same, authored by Samuel Zvi Weltsman of Kalisz (1863–1938), housed at the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem.

- Unknown origin of the KUMEC surname: The exact origin of the surname KUMEC remains unidentified, but we strongly posit that KUMEC could have served as a moniker or nickname for the earliest ancestor, Mordechai.

- Early appearance in records: The designation KUMEC, possibly functioning as a familial or personal identifier, is documented as early as the year 1705 in the Pinkas Kahal of Tykocin (Nadav 1996). This significantly predates the mandated use of surnames in metrical records, which became a legal requirement for Jews in the early 1820s.

- Absence in early metrical records of Wyszogrod: Although the surname KUMEC is absent in the initial metrical records of Wyszogrod, it is evident that the name persisted as a traditional family surname. This continuity is demonstrated by its reappearance in the Konskie 1824 birth record of Mortek, Mendel KUMEC’s son. This suggests that the surname KUMEC has deep historical roots within the family, possibly originating as a personal identifier and subsequently being maintained as a familial surname despite the legal changes governing surnames for Jews in the early 19th century. The investigation highlights the importance of considering alternative sources, such as community records, in genealogical research, especially when surnames predate legal requirements.

- A rabbinical line: Mordechai, the earliest progenitor of the lineage, held a religious position (indicated by ‘Moreinu HaRav’ above). Consequently, he marks the initiation of what is likely a minor rabbinical line, extending through subsequent generations to the BAUM family (and very likely continuing through various other KUMEC lines of descendants). This lineage persisted until my great-grandfather, Icek-Meir BAUM, who served as a Rabbinical Judge in Brussels, Belgium, until his passing in 1932.

- Mendel Mortkowicz is mentioned as a Podrabin (Under-Rabbi) in the 1815 birth record of his daughter Ronia, and also in the 1818 birth record of the twins Ronia and Sara. Subsequently, Mendel is referred to as the Rabbi of Konskie in the 1821 birth record of his son Josek (not displayed here). This appears to come close to the information presented in the Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland, Volume I (Poland), Pinkas HaKehillot Polin (published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem). Indeed, the Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Poland provides specific information about the rabbis of Konskie, including R. Yekutiel (his name is recorded in 1827) who was a disciple of the Seer of Lublin (died 1815), then R. Mendel (about 1829, very likely Mendel KUMEC), and R. Joshua of Kinsk.

- Subsequently, KUMEC lineages originating from Konskie spread to various towns and cities across Poland, including Piotrkow, Belchatow, Checiny, Bendin, and Lodz, among others. Over time, these familial lines extended their migration beyond Poland, reaching various locations worldwide such as Belgium, France, the USA, Uruguay, Australia, Israel, and more.

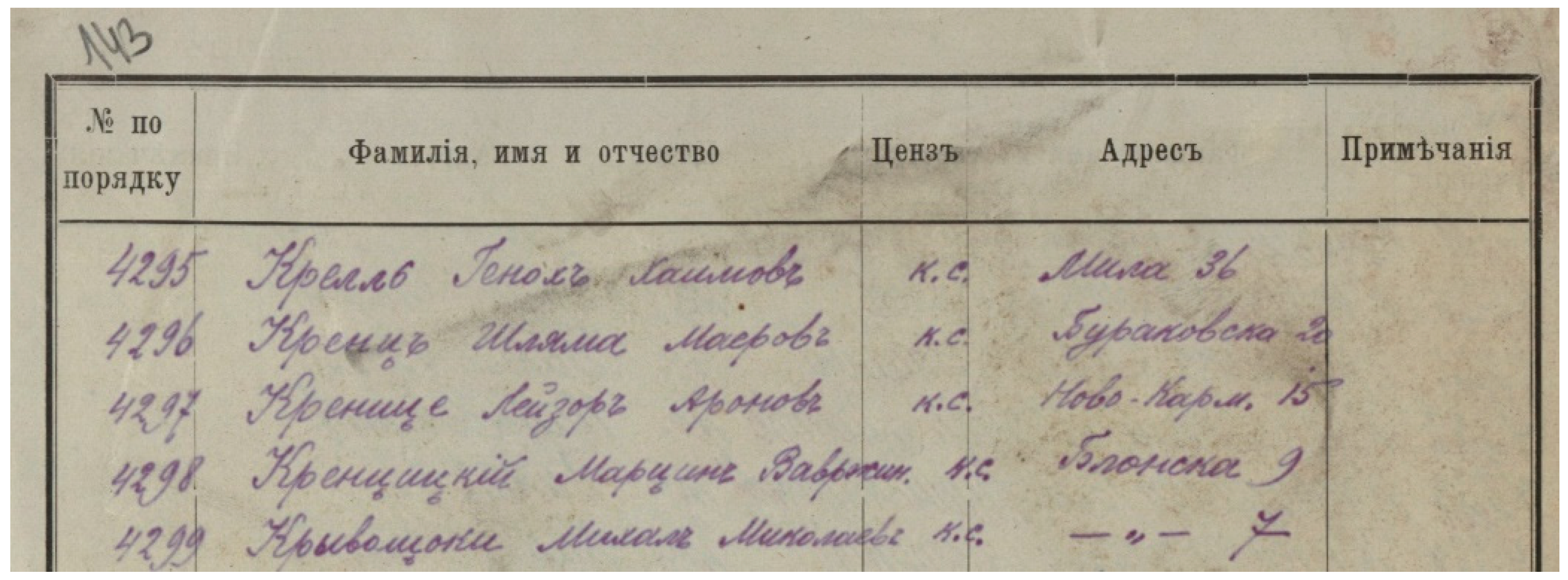

4. Second Case Study: Two KRELL Family Clusters in Warsaw

4.1. The First KRELL Cluster

4.2. Warsaw: The Metrical Records

4.3. Warsaw: The Okopowa Jewish Cemetery

4.4. The Second KRELL Cluster

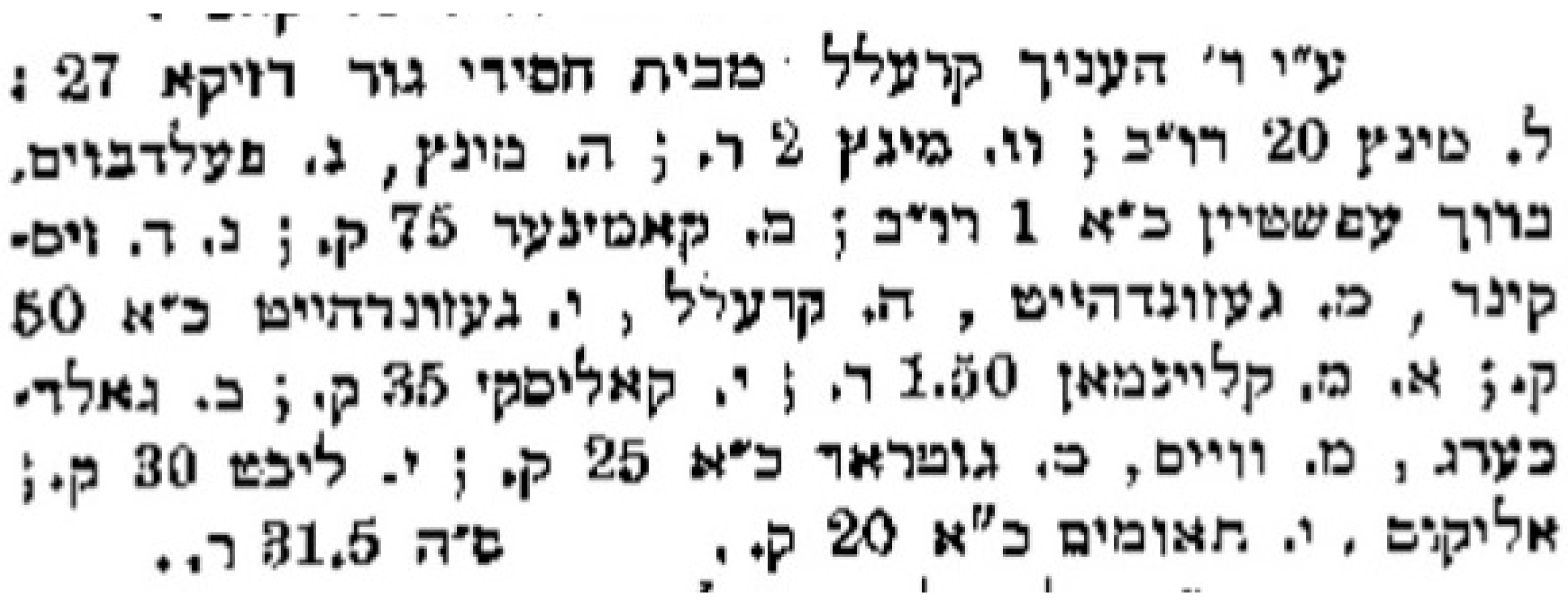

- (i)

- Grandfather David was a Kohen (an heir member of the priestly status descended from Aaron, the elder brother of Moses). Indeed, the male KRELL tombstones in the Okopowa cemetery all have the Kohen ‘open hands’ symbol;

- (ii)

- Several first names (Chaim Leyb, Blima, Malka, Josek, Mordka-Mendel, and more) repeatedly appear in both clusters;

- (iii)

- Physical appearance: a few years ago, I had been startled by a photograph on a webpage of an unknown KRELL man, originally from Uruguay, who had a shocking resemblance to Grandfather David. His ancestry originated from the larger KRELL cluster in Warsaw, and I was told that a few years earlier he had contacted the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, searching for KRELL relatives.4

- First objective: tracing the KRELL ancestral line

- Second objective: identifying Henoch’s parents, thereby merging the KRELL clusters

- Josek KRELL (1819–1875) and Chawa CEJLON (1819–1879), who had four male children: Abram (1842–1921), Mordka (1852–1909), Azryel (1854–1855), and Moszek (1857, fate unknown), and five female children: Gitel (b. 1839), Maryem (b. 1848), Ryfka (b. 1848), Bina/Blima Chaja (b. 1855), Chawa (b. unknown, died bef. 1898), and a baby who died at birth (1846), thus, ten children, all born between 1839 and 1857 in Warsaw;

- Chaim Leyb KRELL (1824–1884) and Blima GUTKIND (1824–bef. 1879), who had four male children: Hersz (1852–1854), Mendel (1861, fate unknown), Moszek (1863, fate unknown), and Mechel (1864, fate unknown), and seven female descendants: Malka (b. 1846), Sura (b. 1849), Chawa (b. 1851), Rywka (b. 1853), Fajga (b. 1859), Rojza (b. 1863), Dwojra (b. 1865), and likely another girl,9 Gitel (no birth record), thus, twelve children, all born between 1849 and 1865 in Grodzisk and/or Warsaw.

- Two of Josek’s male children, Abram (b. 1842) and Mordka (b. 1852), also fall within the right age range to potentially have fathered Henoch (born around 1865–1870). Mordka indeed had a son named Henoch, who died young in 1879; see footnote 2. The epitaph on the tombstone of that young Henoch indeed states ‘My son, a child’, which eliminates the possibility of that Henoch being my great-grandfather and, most certainly, the likelihood of his father Mordechai being the searched-for father of my Henoch. As to Abram and his wife Sura Fajga MALINIAK, they begot 10 children between 1862 and 1882, but there is no indication that they had a son named Henoch. That option will be shown to be wrong

4.5. Furthering the Search

4.6. The Solution

4.7. Closure—Conclusions

- During the 20th century, the numerous KRELL descendants from Mszczonów, Grodzisk Mazowiecki, and Warsaw have spread to various countries, including Belgium, France, Israel, the USA, Uruguay, Australia, and more.

- From the present genealogical data, not all of them being presented here, it is clearly apparent that different Kohanim families were more likely to be wedded with each other: the records show that multiple intermarriages occurred between and within Kohanim branches including KRELL, GROSBARD, RECHTDINER, and more. Kohanim may be recognized by the characteristic open hands symbol on their (male) tombstones, such as on the grave of Chaim Leyb KRELL; see Figure 22 (note the inclusion of the middle name Yehuda).

- The parents of Sura Ruchla RECHTDINER are still unidentified. This obstacle represents a challenging merging issue similar to that described here for Henoch, namely, linking two RECHTDINER clusters.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Personal communications from Hadassah Lipsius (JRI-Poland) and Ania Przybyszewska-Drozd and Yale Reisner (the Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw). |

| 2 | An 1879 grave exists in Sector 71 for a Henoch KRELL, whose father was Mordechai/Mordka HaKohen, ‘still alive’. The epitaph states ‘My son, a child’, which eliminates the possibility of this Henoch being my great-grandfather and most certainly, the likelihood of Mordechai being the searched-for father of my Henoch. There is also a Henoch KRELL, born in 1877 in Lodz, son of Szmul Moszek and Rywka Leah SALOMON, died in Konskie in 1940 together with his wife Bina Przedborska, in unknown (but likely violent) circumstances. So far, a connection with the Warsaw KRELL lines has not been found. |

| 3 | Stanley Diamond, personal communication. |

| 4 | Anna Przybyszewska, personal communication. |

| 5 | Petje Schroder and Anna Przybyszewska, personal communications. |

| 6 | https://metryki.genbaza.pl/, https://geneteka.genealodzy.pl/, both sites accessed on 21 March 2024, courtesy of P. Schroder. |

| 7 | Interestingly, surnames are inherited in a similar way as specific regions of the Y (male) chromosome. For this and other scientific aspects of such correlative issues, see (Rhode et al. 2004; King and Jobling 2009; Manrubia et al. 2003; Wagner 2013). |

| 8 | The focus here is on tracking the patrilineal surname KRELL since the objective is to search for Henoch’s parents. |

| 9 | Eve Locker (USA) and Inbal Kandel (Israel), personal communications. |

| 10 | Blima might have been born in the same year as Chaim Leyb. Indeed, an 1824 birth record in Grodzisk was uncovered for a Bluma GUTKIND: 1824/B109, father Moszek (22), mother Reyzly Michlow (18). |

| 11 | Source: The National Library of Israel (NLI). |

| 12 | See above Note 11. |

| 13 | Personal communications from A. Krell (USA), S. Krell and L. Krell (Uruguay), M. Taub (Israel), I. Kandel (Israel), E. Locker (USA), M. Herman (USA), D. Msellati (France), and Ch. Nissimov (Israel). |

| 14 | M. Shefi and M. Wzorek, personal communication. |

References

- Bar Yuda, M., and Z. Ben-Nachum. 1959. Sefer Tykocin. NYPL Digital Collection. Available online: https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/yizkor-books/yzk-nybc314065/bar-yuda-m-ben-nachum-z-sefer-tiktin (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Ben Azriel, Shmuel. 1770. Hagorat Shmuel (Shmuel’s Belt). Frankfurt-Oder. [Google Scholar]

- Czakai, Johannes. 2021. Nochems neue Namen: Die Juden Galiziens und der Bukowina und die Einführung deutscher Vor- und Familiennamen 1772–1820. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, pp. 82–112. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, N. T. 1975. Otzar HaRabanim (A Treasury of Rabbis). Tel Aviv: M. Greenberg Printing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kalik, Judith. 2018. Movable Inn:. The Rural Jewish Population of Minsk Guberniya in 1793–1914. Warsaw and Berlin: De Gruyter Open, p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Arieh Lajb. 1787. Pnei Arieh (Arieh’s Face). Nowy Dwor. [Google Scholar]

- King, Turi E., and Mark A. Jobling. 2009. What’s in a name? Y chromosomes, surnames and the genetic genealogy revolution. Trends in Genetics 25: 351–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrubia, Susanna C., Bernard H. Derrida, and Damián H. Zanette. 2003. Genealogy in the era of genomics. American Scientist 91: 158–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, Tsvi Yechezkiel. 1933. Divrei Gdolim (Words from the Great Ones). Pietrkow, (The Book Includes Milei de-Avot (Words of the Fathers) by Rabbi Asher KUMEC and Rabbi Moshe KAC (K”C), Known as “The Great Ones from Tykocin”). [Google Scholar]

- Nadav, Mordechai. 1996. Pinkas Kahal Tiktin (The Minutes Book of the Jewish Community Council of Tykocin (1621–1806)). Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Science and Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, Hayim. 1971. Sefer Wyszogrod. NYPL Digital Collection. Available online: https://orbis.library.yale.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=1149853 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Rhode, Douglas L. T., Steve Olson, and Joseph T. Chang. 2004. Modelling the recent common ancestry of all living humans. Nature 431: 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, Hanoch Daniel. 2008. Tracing pre-1700 Jewish ancestors using metrical and rabbinical records. Scripta Judaica Cracoviensia 6: 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Hanoch Daniel. 2013. Selected Lectures on Genealogy: An Introduction to Scientific Tools. Rehovot: The Weizmann Institute of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Dov-B., and Neil Rosenstein. 1999. Avnei Zikaron (Stones of Remembrance). Elizabeth: The Computer Center for Jewish Genealogy. [Google Scholar]

- Wein, Abraham, and Rachel Grosbaum-Pasternak. 1999. Pinkas Hakehilot of Poland (Vol. VI, Poznan). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. [Google Scholar]

| YEAR | TYPE/REC# | SURNAME | FIRST NAME, AGE | YEAR OF BIRTH | DATE OF EVENT | PLACE OF BIRTH | RESIDENCY | FATHER, AGE, OCCUPATION | MOTHER, AGE | SPOUSE | COMMENTS, ADDRESS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1819 | B/4 | KREL | Josek | 6 Jan 1819 | Mszczonów | Mszczonów | KREL Hersz, 20 | Łaie, 19 | House 100 | ||

| 1821 | B/25 | KRELL | Ester | 20 Mar 1821 | Mszczonów | Mszczonów | KRELL Hersz, 22, stall keeper | Łaja z MICHLOW, 21 | House 27 | ||

| 1821 | D/19 | KRELL | Ester, 3 months | 1821 | 18 Apr 1821 | -- | Mszczonów | KRELL Herszek, stall keeper | Łaja z MOŚKÓW | died in House 27 | |

| 1822 | B/26 | KREL | Jankel | 7 Apr 1822 | Mszczonów | Mszczonów | KREL Hersz, 26, stall keeper | Łaja z MECHLÓW, 24 | House 27 | ||

| 1823 | D/55 | KRELL | Layb, 76 | 1747 | 30 Jul 1823 | -- | Mszczonów | butcher | -- | Malka z HERSZKÓW | died in House 99; witness: Hersz KRELL, butcher, son |

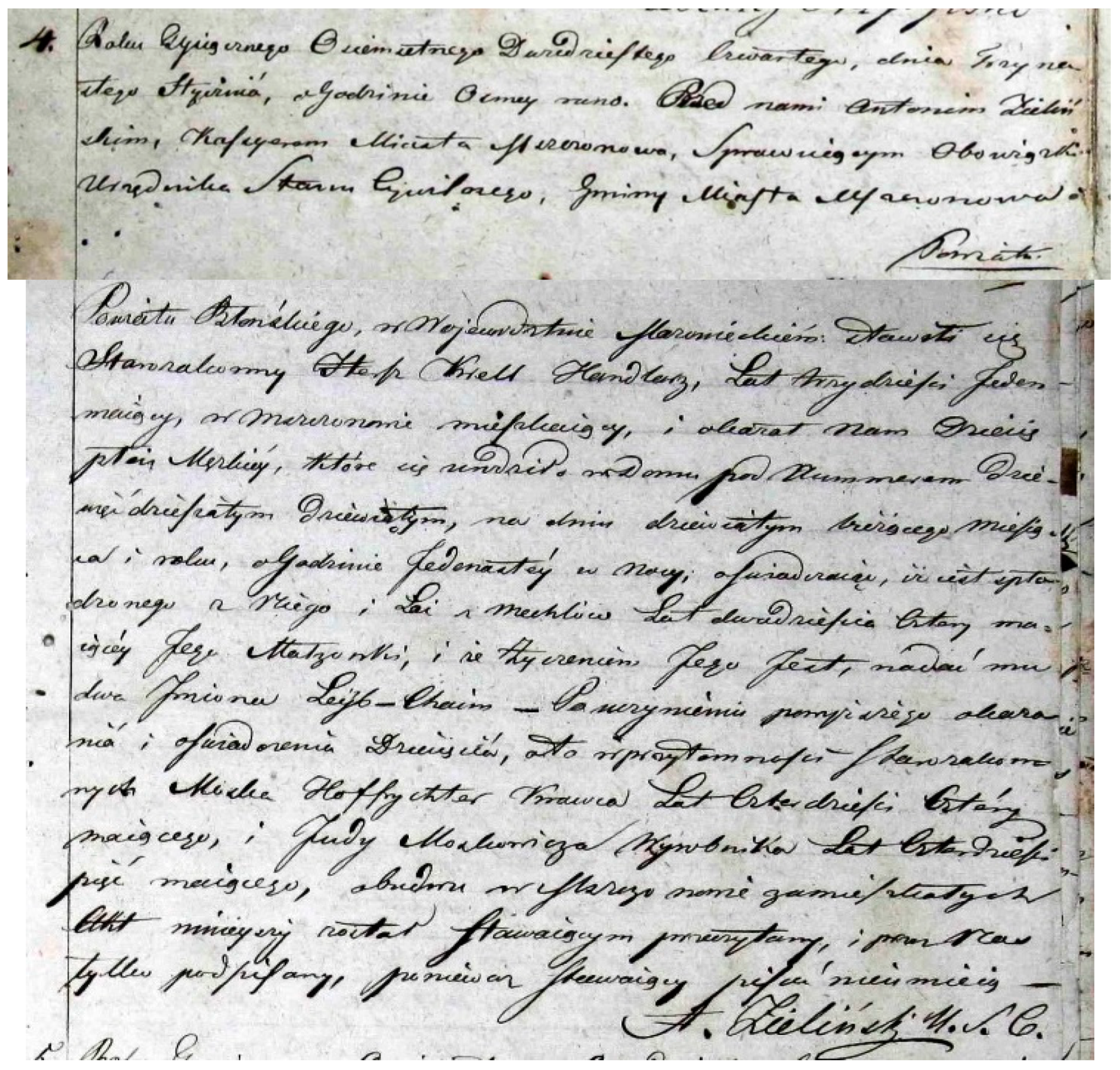

| 1824 | B/4 | KREL | Leyb Chaim | 9 Jan 1824 | Mszczonów | Mszczonów | KREL Hersz, 31, trader | Łaja z MECHLÓW, 24 | House 99 |

| YEAR (REG.) | TYPE/REC# | SURNAME | FIRST NAME | DATE OF EVENT | PLACE OF BIRTH | RESIDENCY | FATHER, AGE, OCCUPATION | MOTHER, AGE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1846 | B/25 | KREL | Malka | 16 Jun 1846 | Grodzisk | Grodzisk | Chaim Lajb KRELL, 23, dealer | Blima GUTKIND, 21 | |

| 1854 | D/15 | KRELL | Hersz | 24 Aug/5 Sep 1854 | -- | Grodzisk | Chaim Lejb KRELL | Blima (GUTKIND), | One-year-old baby; witness: Mordka Szlama GUTKIND, szkolnik, age-35 |

| 1855 | B/35 | KRELL | Sura | 13 Jul 1849 | Grodzisk | Grodzisk | Chaim Lajb KRELL, 32, trader | Blima GUTKIND, 27 | witness: Mordka Szlama GUTKIND, szkolnik, age-36 |

| 1855 | B/36 | KRELL | Chawa | 18 Mar 1851 | Grodzisk | Grodzisk | Chaim Lajb KRELL, 32, trader | Blima GUTKIND, 27 | witness: Mordka Szlama GUTKIND, szkolnik, age-36 |

| 1855 | B/37 | KRELL | Ryfka | 20 Jul 1853 | Grodzisk | Grodzisk | Chaim Lajb KRELL, 32, trader | Blima GUTKIND, 27 | Late registration due to father’s illness; in the two previous records, late registration because father was unaware of the law |

| 1859 | B/100 | KREL | Fajga | 28 Nov 1859 | Czyste | Czyste village | Chaim Lajb KREL, 37, trader | Blima GUTKIND, 37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wagner, H.D. Researching Pre-1808 Polish-Jewish Ancestral Roots: The KUMEC and KRELL Case Studies. Genealogy 2024, 8, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020035

Wagner HD. Researching Pre-1808 Polish-Jewish Ancestral Roots: The KUMEC and KRELL Case Studies. Genealogy. 2024; 8(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleWagner, Hanoch Daniel. 2024. "Researching Pre-1808 Polish-Jewish Ancestral Roots: The KUMEC and KRELL Case Studies" Genealogy 8, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020035

APA StyleWagner, H. D. (2024). Researching Pre-1808 Polish-Jewish Ancestral Roots: The KUMEC and KRELL Case Studies. Genealogy, 8(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy8020035