1. Introduction: An Invitation and Relational Protocols

“Imagine yourself in the forest, around a campfire; it is pitch dark all around. The stars are shining brightly overhead, and a soft warm breeze is blowing around you—just enough to keep down the mosquitos”.

We choose to begin our manuscript with the quote above which describes the educational setting Yakama peoples have built and sustained for thousands of years. Elders and storytellers are central in our most important forms of teaching and learning, as generations learn the values and responsibilities that are key for humans to exist and thrive in a respectful relationship with place. The opening quote is both a description and an invitation; readers are provided with a description of a beautiful setting on Yakama lands and are invited to envision education from a Yakama perspective. With the setting described, and an invitation granted (and accepted), the next step is to collectively begin the process of storytelling. We honor this approach in our work and are delighted that you have accepted our invitation to join us in the contemporary sharing and learning process made possible through an academic manuscript.

We wish to honor the Indigenous protocol of introductions so that readers will know who we are and thus we are responsibly accountable to our communities. All authors have ties to Yakama peoples, and thus Yakama lands and kinship networks, although some authors are doing the important work of connecting Yakama people and places with other communities and kin. We share a brief introduction of each author below to respect Indigenous protocol and to demonstrate to readers how the focus of our paper, genealogies of knowledge, is important ethically, intellectually, and relationally. By introducing ourselves, we invite readers into an intentional relationship with us and our work.

Ink nash waníksha Tuxámshish. Kw’aɬániish áwyatwiisha sapsikw’aɬáma. Papx̱wípx̱wisha pimakínk tiináwitki ku pawáḵ’itsha mɨnán wapíitatnan i’yax̱ta ku panáktux̱ta pɨmyuuk nishayasyaw ku laak tun shix̱ áw’yax̱ta niimípa sɨ́nwitpa. Ku matash nísha ts’wáaywit naktúx̱t piimipáynk. Kush áwɨnta, “chaw nam px̱wípx̱wita ámishnisha tswáywit anatún nam átḵ’ix̱sha.” My name is Tuxámshish. I’m pleased to gather with distinguished teachers. They are worried about their own peoples’ Native culture and language. I want you to know this: if you find anything of value in my Elders’ teachings in this manuscript, I give you my permission to take it home to your people and show them for comparison.

Shix páchway! Ink nash waníksha Michelle Jacob. I am a member of the Yakama Nation and am deeply honored to learn from our Elder and collaborator Tuxámshish, who cares for, sustains, and strengthens Yakama genealogies of knowledge in our languages and stories.

Cama’i, gui Leilani Sabzalian Eugene, Oregon-mi sullianga anglilu. Ilanka Cirniq-miut. I greet you as an Alutiiq educator who has been privileged to learn from Tuxámshish, including her life story and the Yakama stories she has gathered from Elders in her community.

Dáanzho! Haeyayln Muniz, Abáachi asht’íí, Llanero. As a Jicarilla Apache scholar, I am thankful and honored to join this community of Indigenous scholars.

Kevin Simmons nayka nim, nayka chaku khupa Grand Ronde, Oregon pi Muckleshoot, Washington. I am honored to be working beside and learning from Indigenous scholars who promote and center their respective Indigenous knowledges and experiences they represent.

Kw’aɬá nam wyánawi. Ink nash waníksha Regan Anderson kush wa wapiitaɬá Ichishkíin Sɨ́nwitki. I am so grateful for the mentorship of Tuxámshish and for the privilege to work among this team of scholars and the knowledge they hold and share.

2. Yakama Place, Thought, and Knowledge

Now that we have introduced ourselves, we briefly introduce the place that is most central to the work we describe in this manuscript. From an Indigenous perspective, knowledges are rooted in place; teaching and learning are relational activities that carry responsibilities for relationships among human and more than human relatives. From Indigenous ontology and epistemology, relationality is an interconnected web of relationships we have with one another and with the world around us which guides us in our everyday lives. Living and being in a relationship with the world around us keeps us connected to the strength and knowledge of our ancestors, as we work to build a healthy and sustainable present and future for Indigenous people (

Minthorn et al. 2021). To honor this approach, we share briefly about Yakama peoples, places, and stories.

The main project activities we discuss in this manuscript take place on Yakama homelands. Yakama peoples belong to the cultural group of Sahaptin-speaking Indigenous peoples across the Columbia River Plateau in the U.S. Pacific Northwest (

Rigsby 2009). Readers can learn more about Yakama peoples and places in other works (

Beavert 2017;

Jacob 2013). Briefly, Yakama peoples understand that being in a respectful relationship with our Indigenous homeland is both a privilege and a sacred duty rooted in teachings that are thousands of years old carried by our Elders and shared across generations. In Yakama knowledge systems, these teachings are based in our very homelands, and the teachings are old—extending back to what many Elders call legendary time, a time before humans existed. According to these teachings, humans are not the first people, but rather all other beings are the first people, and in Yakama storytelling traditions, the First People can talk, walk, and sometimes have supernatural powers like flying great distances, causing dramatic weather changes, or creating large landscapes such as mountains or foothills. Yakama legends and stories are embedded with lessons, traditional practices, and values for their people across the generations and for the broader community. Next, we turn to one revered story that was of special importance in the larger project we discuss in this manuscript.

3. Origin of Basketweaving: Summary of Story

Stories are an important way to introduce readers to Yakama homelands and culture. Here, we provide a brief description of “The Origin of Basketweaving”, the focus of our article. For readers wishing to engage a longer format of the story, we direct you to the book

Anakú Iwachá: Yakama Legends and Stories (

Beavert et al. 2021). This story is treasured by Yakama peoples, and versions exist across several Indigenous communities as our traditions of traveling, sharing, and learning mean we have a vast network of relations among kin and knowledge systems. Such methodologies emphasize the importance of sharing and building relationships in the production of knowledge and in creating and sustaining educational practices and systems. Our storytelling traditions remind us that from an Indigenous perspective, education is intended to support individual and collective well-being. The story recalls how the Łátaxat (Klickitat) basket tradition, for which Yakama peoples are famous, originated and honors knowledge treasured by our peoples from Łátaxat homelands near present-day White Salmon, Washington, within the beautiful Cascade Mountain. In the story, we witness the centrality of genealogies of relational knowledge. Nank (Cedar Tree) is the primary teacher within the story, and when Nank first addresses Sɨnmí (Squirrel), he refers to her as “my little sister”, marking their close relationship, and indicating the learning context is one of love and care. The story teaches that Sɨnmí is a rather pitiful person who lacks skills, confidence, and direction in her life. She does not feel she has anything to contribute to her community. Nank is troubled by this and decides to help Sɨnmí by teaching her each step of how to gather materials, conceptualize, and weave a basket. Nank models for us the importance of wise and generous teachers, and one of the first steps in Sɨnmí’s learning is to gather cedar roots in a respectful and appropriate way. In the story, Sɨnmí learns to understand that she is part of the community, and she builds both confidence and trust in herself and all her relations around her. When Sɨnmí feels unsure of how she can come up with designs for her basket, many helpers and teachers step forward to remind her of the generosity and abundance in the land: Pátu (Mt. Adams) invites Sɨnmí to witness the shape of a peaked mountain as a beautiful design she can use; Wáxpush (Rattlesnake) invites Sɨnmí to look closely at the designs on his back and suggests that these can inspire a pattern of edging along the top of her basket. Many more relatives and teachers step forward to assist and inspire Sɨnmí to envision her future work as a basket weaver. After completing all of the many steps involved, Sinmi learns that her basket is only a success if it is woven watertight. Once a watertight basket is achieved, Sɨnmí learns she must give away her first successful baskets as gifts to Elders. The story ends with reminders that individual achievement is important and praiseworthy but is only most successful when done in ways that strengthen the community. The story reminds us to understand everyone has a gift to offer our community, even those like Sɨnmí who may seem pitiful and lacking skills and direction. We learn that through kind and loving teaching, strong collectives always benefit from nurturing and inspiring individuals to reach their highest potential. Sɨnmí thus becomes a great teacher and role model in the process, and the foundress of our famous Łátaxat (Klickitat) basket tradition.

4. Yakama Values

The story we summarize above is an example of how Yakama values are interwoven in our storytelling traditions. Learners who engage our stories quickly learn which values are important to Yakama peoples and places. The emphasis on collective well-being, kindness, generosity, and persistence are honored in the Origin of Basketweaving story. Yakama Elders strongly affirm the importance of our cultural values (

Wilkins 2008). Yakama values are caretakers in their own right, moving relationally through generations and offering strength and knowledge deeply embedded in place (

Jacob 2013). Values continue to be shared and taught among Yakama families within their homes and community (

Anderson 2022;

Sutterlict 2022) and also incorporated into modern contexts of education (

Wilkins 2008). We are witness to so many of these values through storytelling, and here we focus on one such story, the Origin of Basketweaving. The Basketweaving story includes values that guide us to accept and follow teachings gracefully when offered and remind us of the careful observation involved in the learning process that encourages us to go out and

find knowledge rather than merely take it in (

Beavert 1996). This responsibility extends to the reception of knowledge, too, and taking on leadership to carry that new knowledge forward, gifting it out in ways that lift others up and tend to their unique strengths. The process of knowledge growth is also collaborative in the way it adapts to meet the needs of both those sharing knowledge and those welcoming it in. Because learning is reciprocal, it is paced according to relationships and leaves room for many different pathways in reaching a given goal. As we see with Nank (Cedar Tree) and Sɨnmí (Squirrel), there is celebration throughout the process as growth is recognized along the way, and many new relationships are fostered through Sɨnmí’s path as knowledge is explored. Another prominent Yakama value we witness in this story and beyond is that knowledge is responsibility (

Ayer 2021) and our gifts—knowledge, skills, creations—are not mastered for our own benefit but to give back to the community as a whole, particularly honoring Elders who have long shared their knowledge (

Beavert et al. 2021).

Stories and storytelling place Indigenous people in webs of relationships with sacred responsibilities. One example from the Origin of Basketweaving story is Nank’s (Cedar Tree) concern for Sɨnmí (Squirrel), “this tree would watch this girl and he worried about her. He was sorry for her because nobody wanted to help her. “‘That poor girl. She does not know all the things a young girl should know’” (

Beavert et al. 2021, p. 89). Nank’s concern for Sɨnmí is an expression of honoring relationships, guidance and teachings, and coming of age into adulthood. Through these interactions, Sɨnmí came to understand the importance of Elder teachings, knowledge through doing, and cultural values and practices. Nank’s guidance and teachings provided elements related to the importance of traditional practices and protocol and the journey into wisdom. These traditional skills and knowledge are holistic and bridge a connection between healing and wellness. A holistic approach nurtures connections between humans, more-than-humans, and the environment where they all co-exist together seeking balance (

Boivin et al. 2023). The story also promotes an intergenerational connection between Elders and the community (

Gould 2005;

Jacob 2013) and reminds us of our responsibility to one another. Intergenerational connections are an integral value associated with well-being and healing within Indigenous communities and maintain the ability and power to promote a community’s collective identity and connection to culture (

Boivin et al. 2023). These engagements provide space for stories and experiences which are vital as they connect to spiritual, emotional, mental, and physical well-being; it is ultimately a “healthy” process (

Cajete 2017).

5. Stories and Storywork

Stories are the backbone of Indigenous educational systems (

Archibald 2008;

Cajete 2015,

2017). While stories have always been understood as an important foundation in Indigenous education, the world of academic peer-reviewed publication is more recently benefitting from a growing awareness of this, including recently published findings across international contexts such as Nigeria (

Ikpo 2023), Canada (

Poitras Pratt 2019), Australia (

Weuffen et al. 2019), and New Zealand (

Rameka 2021) and in Indigenous-centered multicultural contexts (

Windchief and Ryan 2019). While Indigenous communities have our own distinct languages and relationships with place, we share many cultural teachings, including the centrality of stories and storytelling traditions in our Indigenous education systems that have been in place for thousands of years before Western schooling systems arrived in our lands. Indigenous Elders continue to generously carry and share stories, and in doing so uphold Indigenous education systems that have sustained our peoples. We are honored to add our work to this growing body of literature.

Indigenous communities have many stories of cultural and educational importance. Our manuscript focuses on one such story, and our discussion of The Origin of Basketweaving in the previous section highlights the array of values and teachings that are communicated in a single story. Stories are an integral way of learning for Indigenous people. They connect communities to land, identity, community, and culture and utilize intergenerational relationships in fostering and teaching well-being. Stories hold memories, emotion, knowledge, and power (

Kovach 2018). Whether stories shared are lived experiences of our truth, or sacred stories to be told during certain times of the year, stories have the power to teach us about collective movements, the people and places we come from, and honor lessons from our relations with human and more than human kin (

Jacob 2021). Stories carry the cumulative knowledge of our communities developed over generations and millennia. Stories teach us about our homelands, our roles and responsibilities in the world, our values and ways of life, or important life lessons. Stories can also be “just for fun”, bringing us together or making us laugh (

Archibald 2008, p. 83).

Storytelling is well suited for Indigenous knowledges, which are holistic and embody relationality (

Wilson 2008) and can honor and communicate the interconnectedness of life. As a way of sharing knowledge, storytelling contextualizes knowledge about the world and our place within it for learners and respects the capacity of listeners to make meaning in relation to their lives. Storytelling also allows for multiple interpretations and layered meanings, as lessons and understandings may deepen over time (

Simpson 2017).

Storytelling can also be used to remind us of our values and teachings to help us live in respectful relation with one another and place. An Elder might tell a story to a young one who needs to be reminded of the value of respect or to admonish them not to be greedy. Rather than directly impose these lessons, a story told by the right person at the right time can “go to work on your mind and make you think about your life… making you want to live right” (Nick Thompson, as cited

Basso 1984, pp. 41–42). A story told about the Legend of the Lost Salmon might remind a child not to be careless, greedy, or wasteful with salmon and other precious gifts, or could remind them of the important role and value of grandparents and Elders in our communities. The Legend about the Sun and Moon might remind youth not to gossip, be vain, or insult others. (

Beavert et al. 2021). In a relational context, stories can activate processes of deep reflection and relational accountability (

Wilson 2008). The journey and gift of knowledge come with the responsibility of finding meaning and application.

Stories are also embedded in the land (

Stiegman and Pictou 2023). When stories are told about our homelands or other important places, we are invited to remember our relations, responsibilities, and how to live in right relation (

Tynan 2021;

Dudgeon and Bray 2019;

Basso 1984). Storytelling can also be healing, as stories can deepen our connections to our kinship systems and ways of life, which are medicine. Through our families, communities, and Indigenous knowledge systems, we strengthen our identities and sense of belongingness. Healing occurs through the (re)connection to cultural practices such as prayer, ceremony, and connection to our natural environment which can lead to hope, harmony, balance, wellness, and how to be a good relative.

Working with stories in education is a gift as well as a responsibility for both storyteller and listener; this relationship is reciprocal. As we are gifted stories, we have a responsibility to not only make meaning but embody values through our actions and carry forward this knowledge. Given the role stories have in shaping our worldviews, and the reality that Indigenous cultures, experiences, histories, knowledges, and their accompanying philosophies are independent and unique from community to community, learning how to work with Indigenous stories respectfully can be challenging. In her work with Coast Salish Elders, Stó:lō scholar Q’um Q’um Xiiem

Jo-ann Archibald (

2008) offers us a path to engaging “Indigenous storywork” in education, which grounds storywork and pedagogy in the principles and values of “respect, responsibility, reciprocity, reverences, holism, interrelatedness, and synergy” (p. ix). This approach reflects the interrelatedness between the emotional, intellectual, physical, and spiritual dimensions of learning and life and situates storytelling as a process of “educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit” (p. 143). Through this perspective, story and storytelling extend beyond analytical or intellectual exercises and become sustaining practices for communities to promote well-being, healing, and resurgence (

Simpson 2017).

Drawing on the power of storytelling and storywork in education, we turn to an example of storywork in education and research as part of a grant-funded project designed to utilize Yakama storytelling to transform systems intended to serve our peoples.

6. Materials and Methods

Our project is based in the traditional homelands of Yakama peoples, and we use the recently published collection of Yakama stories,

Anakú Iwachá, as a key material guiding our work focus and approach (

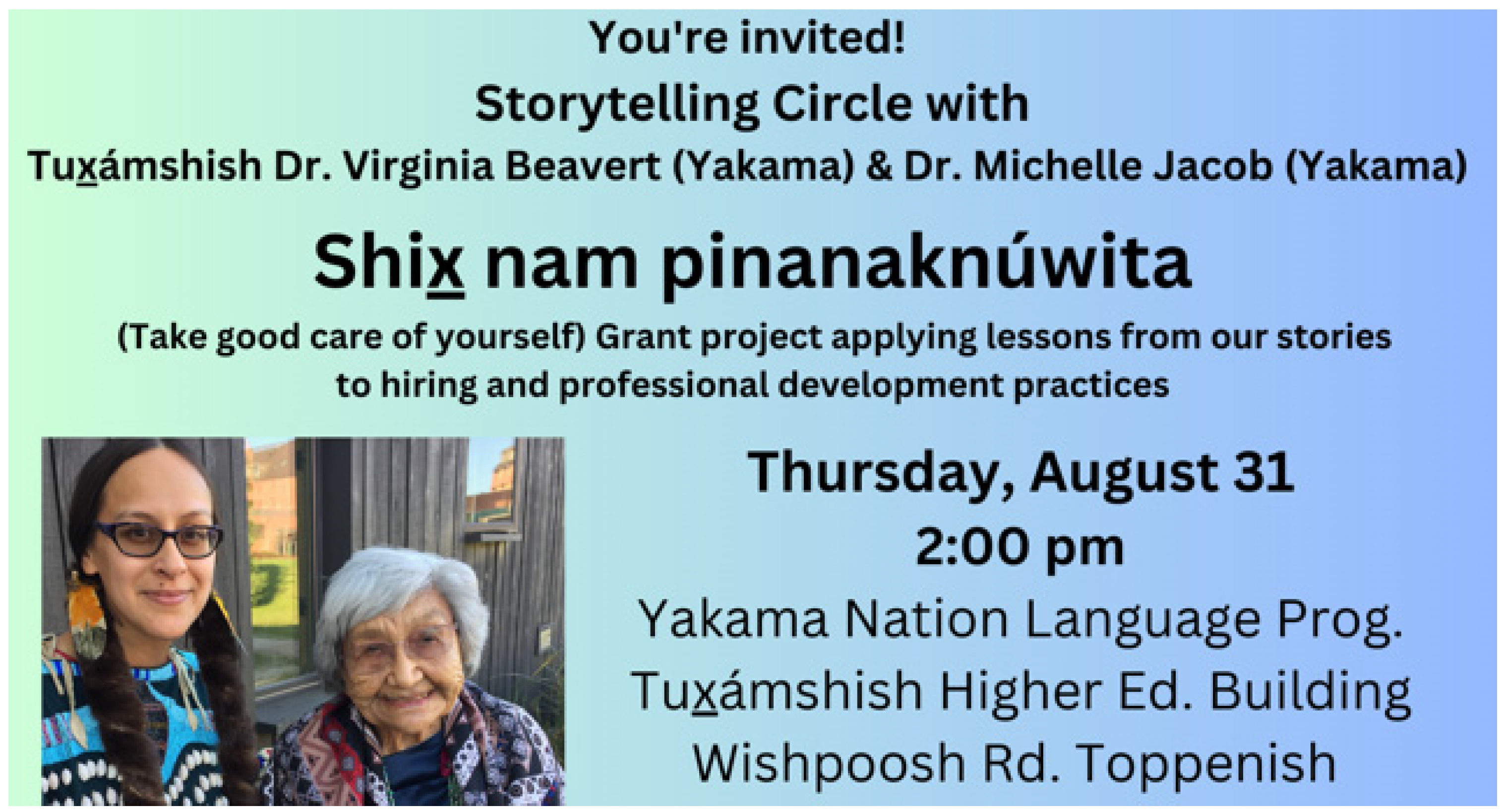

Beavert et al. 2021). This collection of stories is the cumulative effort of many Elders, ancestors, artists, and leaders; these are the stories deemed most important to share with a broad audience to help guide us on a path of learning to be good relatives. Ethical practices of respect, reciprocity, and relationality guided our actions as we came together in collaboration. Relationships are foundational and at the heart of who we are as Yakama people. Fostering meaningful relationships throughout this process ensured we heard and respected everyone’s voice, ideas, and presence. Our method involved multiple meetings to develop and confirm a process for hosting a storytelling circle. The storytelling circle reflects the cultural and ethical practices of establishing relationships, knowledge sharing, and honoring the contribution of knowledge by deep listening. Through the process of hosting a storytelling circle, we not only strengthened our relationships with one another, but it also provided us with the opportunity to form a respectful relationship with stories and new knowledge as a result of our sharing. Drawing from existing material and experiences, we knew key principles for the storytelling circle include the following: (1) importance of Elder presence and leadership; (2) preferred focus on oral tradition; (3) simplicity, brevity, and clarity in written materials shared at the circle; (4) inviting all circle participants to reflect and share.

Guided by the Yakama values of acceptance and following of teachings, relationality, and story as knowledge, described earlier in this manuscript, we partnered with key stakeholders in the community, including local schools, the Yakama Language Program, and the Yakama Nation Higher Education Program. We hosted two storytelling circles, one at a cultural event hosted at a public school on the Yakama Reservation and one at the Yakama Nation Higher Education Program. Invitations were delivered by word of mouth, email, and text message. The invitation list was drafted by the project leaders and included Elders, educators, and Tribal program leaders and staff who hold key positions within educational and Tribal programs intended to serve Yakama peoples. A sample invitation is shown in

Figure 1.

At the storytelling circle, our Elder shared the Origin of Basketweaving story (summarized above). We then engaged in dialogue and reflection, examined lessons that emerged from the story for participants, and began applying these lessons to our workplace settings, roles, and responsibilities. It was agreed upon that we needed to create a resource guide with Yakama values that can be used for everyday life, within school settings, within the workforce, and in interactions with outside agencies. The resource guide honors Yakama values, our way of life, and relationality and promotes wellness and healing. After the first storytelling circle, the project leaders met and reviewed comments shared at the storytelling circle and developed a resource guide to inform and improve future storytelling circle processes. After drafting and revising the resource guide, we invited storytelling circle participants back to the circle, shared the guide, and gathered additional feedback on strengths and suggested revisions. We report the results in the next section.

7. Intentional and Meaningful Engagement

The intention of the project was to engage leaders in a storytelling circle as a way to place Yakama knowledges at the center of systems transformation discussions. The research team, and more broadly our Yakama community, know the power of stories and storytelling as important knowledge systems. However, contemporary bureaucracies oftentimes are pulled in other directions that center Western ways of knowing in policies, procedures, and expected behaviors—away from our Yakama knowledges contained within our stories. Our storytelling circle and this manuscript are efforts to recenter Yakama knowledges.

8. Developing a Yakama Storytelling Circle Model

Figure 2 is a summary of the dynamic process and content of our storytelling circle. We created this model after our first storytelling circle in June 2023 and revised it based on project team discussions in July and August. We took the revised model to our storytelling circle in August 2023 and discussed it with participants. We then revised it again based on participant feedback, our own learning in the storytelling circle process, and team meetings. Importantly, the initial model was more hierarchical, with key components stacked in layers, indicating foundational teachings that served as the base for additional process components. While this approach honored some teachings as foundational, and in a basic way mimicked basketweaving in that there is an upward progression, we ultimately decided that an ongoing and circular model was more appropriate as the components relate to and nourish each other, just as our knowledge systems instruct us to do so. This circular model embodies Yakama values, knowledge, and traditional practices. It also emphasizes relational protocol and the importance of respect, collaboration, sharing, and interconnectedness. Moving and living in a cyclical way is not only interconnected with holistic well-being, but it also reconnects us with Yakama stories, values, and traditions—just as Mother Earth/land lives in a cyclical way, so does life and our interactions. Yakama life is relational and interconnected with land and more than human life, and it is through our oral traditions and stories we are reminded that we too must live in a good way that honors life, community, and Yakama ways of knowing. We also affirm that these stories and practices must be told and retold for all generations of Yakama peoples as part of our responsibilities to carry on precious teachings our Elders have shared. Based on our model and the dynamic process we engaged, we report two key reflections from our project.

9. Reflection 1: Importance of Elders in Schools

Educational leaders attended our storytelling circle, including two non-Indigenous school district superintendents who lead public school systems on the Yakama Reservation, one Indigenous statewide leader for Indigenous education, and an Indigenous elected school board member for a public school on the Yakama Reservation. After our Elder finished sharing the Origin of Basketweaving story, we invited attendees to reflect on lessons from the story and apply these lessons to their workplace settings and leadership roles. One of the most powerful discussions happened when one superintendent reflected on the transformative experience he had being in the presence of an Elder teaching and sharing through story. He remarked that he felt such a sense of clarity and focus in this experience, which is rare for his workday experience. This experience allowed him to reflect more deeply on a problem he was facing in his district. He shared that there are a few Native students who are acting out in his district and that their behavior is inappropriate and disruptive at school. The superintendent shared that his district’s current practice is to call the police to remove disruptive students from the school. However, being part of the storytelling circle provided the superintendent with insight that rather than calling the police on students, perhaps his district could address behavior issues by inviting students to spend time with Elders. At that moment, the superintendent envisioned a culturally sustaining way of educating Indigenous youth—one that shifts away from a criminalization approach to a relational approach that honors Elders and our stories as foundational teaching and learning strengths. The attendees of the storytelling circle affirmed this idea, and other attendees with experience teaching in the Yakama Nation Tribal School shared that they had witnessed a similar approach at their school; they shared an example of an energetic (and misbehaving) classroom of eighth-grade students who, when an Elder entered the classroom, sat still, raised their hands to ask questions and participate in discussion, and listened with great respect and focus.

10. Reflection 2: A Relational Approach to the Hiring Process

Another powerful discussion emerged when a program manager for the Yakama Nation reflected on the lessons within the story which remind us of the importance of relationality in all of our work. The discussion focused on the ways in which contemporary bureaucracies can pull our attention away from this important teaching and our Yakama values. Paperwork, emails, meetings, and overflowing schedules can be stressors that shift our attention away from perhaps the most important work, honoring Yakama values in all that we do. As Yakama peoples, it is our responsibility to do so. For non-Yakama peoples who work on Yakama homelands, it is also a cherished responsibility to do so. Yet, organizational structures can fail to support this approach. For example, the program manager reflected on their responsibilities in leading and carrying out hiring processes. They shared that the storytelling circle brought to their awareness the importance of relationality in that process, and how they are now reflecting on ways that they can transform the process. A key weakness in the current process is that there is no way to communicate generatively with candidates who do not get hired. The discussion focused on how a transformed process would allow hiring committees to share positive feedback as well as constructive feedback that could help candidates access additional opportunities in the future. This discussion spurred powerful comments from the storytelling circle participants as we reflected on the ways that current human resources protocol often situates the hiring process as being about finding one “winner” and how everyone else by default is a “loser” of that job opportunity. We enjoyed envisioning a process that is more culturally sustaining, and that understands each applicant, like Sinmi, has endless potential to make contributions to our community. We envisioned hiring committees taking a relational approach modeled on Nank’s powerful example in the story that our Elder shared with our circle.

11. Discussion

Ideally, from a Yakama perspective, our knowledges and relational approach would saturate our workplaces all across Yakama homelands. However, until this ideal is achieved, we can continue to gather motivation and encouragement from our storytelling circle. We can take steps to hold these lessons in our awareness in our workplace settings and daily lives. To support this process, as well as to advance the scholarly understanding of the importance of Yakama stories, we offer the model as a resource.

We find this current model (

Figure 2 above) to be helpful in serving its intended purpose: to remind people of the important benefits and teachings of our storytelling circle. However, we fully intend this model to be dynamic, and we invite readers to adapt it to their own contexts. One note of caution, however, is that we urge readers to take seriously the importance of Indigenous self-determination and Tribal Sovereignty when they are engaging Indigenous stories. Stories are the backbone of our Indigenous education systems and have sustained our peoples in respectful relation with place for thousands of years. Additionally, stories contain teachings sacred to our peoples and assert our most precious values. Stories should be used respectfully in ways that honor and affirm these principles. Stories should not be extracted as pieces of entertainment for non-Native audiences without careful consideration of the importance of Indigenous self-determination and Tribal Sovereignty. Readers of this manuscript can consult the many references we share so that this intention is honored. Doing so upholds the practice of engaging stories for well-being and healing.

Indigenous stories and our storytelling traditions are powerful tools that can teach us about interconnectedness and holism. Our work both affirms and builds on

Archibald’s (

2008) Indigenous Storywork framework that articulates holism as an Indigenous philosophical concept that represents the interrelatedness between intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and physical well-being. Thus, Indigenous stories and storytelling extend beyond the realm of analytical or intellectual exercises and are sustaining practices for communities to promote well-being and healing for Indigenous peoples, and all peoples on Indigenous lands. We invite all readers to consider the importance of stories in the place where you live, work, and learn.

Throughout this manuscript, we have encouraged readers to savor the teaching that stories and storytelling place Indigenous people in webs of relationships with sacred responsibilities. Readers can draw inspiration from the examples of Nank and Sɨnmí we shared from the summary of the Origin of Basketweaving story. Perhaps like our storytelling circle attendees, readers will feel inspired to take a moment to pause and reflect deeply on the highest priorities and values in one’s life.

12. Conclusions

Stories are the central elements of Indigenous education that connect communities to identity and culture and utilize intergenerational relationships in fostering and teaching well-being. Stories are living beings, each with agency; thus, storytelling extends beyond Western knowledge and embodies Indigenous resurgence through promoting holistic perspectives of well-being and healing. Healing involves restoring or repairing relations, in this case, the relationships between administrators and youth and the relationship and role of Elders in schools; the need for relational work is often at the root of fear/mistrust/problems. This process is beneficial especially when leaders and educators have the time and space for deep reflection, as we shared and discussed in Reflection 1 above. So often in contemporary bureaucracies, there is a feeling of time scarcity that prohibits the opportunities for pausing, deeply reflecting, and reconnecting to one’s highest priorities and values as part of our daily work routines (

Jacob 2021).

The superintendent’s reflection in Reflection 1 above underscores the value of providing Elder-guided spaces and time to pause and reflect. His realization that there are alternatives to calling the police on youth who misbehave also highlights the role and value that stories can play in this process. The Origin of Basketweaving models a deep and loving system of relationality and relational accountability, offering a critical alternative to punitive and carceral practices that are pervasive in K-12 schools. In the story, Nank (Cedar Tree) helps Sɨnmí (Squirrel), someone that no one else wanted to help, someone community members avoided. The story provided context for understanding relationality, and the time spent with an Elder in the storytelling circle provided a meaningful alternative rooted in Indigenous restorative practices, “focus on not only repairing, but also building and strengthening relationships and social connections within communities” (

Thomas 2022, para. 4).

Storytelling and reflection can also invite us to reflect on institutional policies and processes we may have inherited or continue to uphold in schools uncritically, processes that do not feel good to us or honor the types of relationality we want to embody. District and institutional processes are not typically rooted in relationality; in fact, they are often designed to distance us from relationships, buffering us through bureaucracy that protects institutions, rather than respecting people and relationships. As the discussion in Reflection 2 highlights, the storytelling circle provided space for educational leaders to envision a more respectful process that honored the candidates who applied, even if they were not chosen. These candidates are still members of the community, and developing a more supportive process to help them refine and articulate their contributions benefits them as well as the broader community. A variety of institutional policies and practices could benefit from a relational lens. As a collective process that fosters critical reflection, the Yakama Storytelling Model offers one way for administrators and educators to engage in this work.

We realize that not everyone is fortunate enough to attend a storytelling circle with a Yakama Elder. Time, funding, space, and administrative tasks for organizing and carrying out such gatherings are barriers. Thus, one approach to sharing the benefits of the storytelling circle is to describe what we did and how we did it and share lessons learned. We do so in this manuscript and hope that our sharing has taught and inspired others to engage in storywork in responsible and respectful ways. Throughout this manuscript, we have offered multiple resources to help teach, affirm, and strengthen readers’ preparedness for engaging storywork.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.J., L.S., R.N.A., H.R.M. and K.S.; Formal analysis, M.M.J. and V.R.B.; Funding acquisition, M.M.J.; Methodology, M.M.J. and V.R.B.; Project administration, M.M.J.; Writing—original draft, M.M.J., L.S., R.N.A., H.R.M. and K.S.; Writing—review & editing, M.M.J., L.S., R.N.A., H.R.M., K.S. and V.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant number 80642—Honoring and sharing the importance of traditional Indigenous storytelling.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. We gathered in a voluntary Elder storytelling circle as part of our maintaining cultural traditions and as such did not involve an IRB.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants voluntarily attended our storytelling circle and consented to participation.

Data Availability Statement

The basis for our storytelling circle is the written version of Yakama stories which are published and available in the book, Anakú Iwachá.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the wonderful people who attended our storytelling circles with our beloved Elder.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson, Regan. 2022. K’aaw Natash Wa Chɨ́myanashma Shapáttawax̱sha Ku Sápsikw’asha Myánashma ’We Are the Parents Raising and Teaching Children’: Raising Yakama Babies and Language Together. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, Jo-ann. 2008. Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ayer, Tammy. 2021. 39 under 39 profile: Elese Washines. Yakama Herald, February 28. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, Keith H. 1984. “Stalking with stories”: Names, places, and moral narratives among Western Apache. In Text, Play, and Story: The Construction and Reconstruction of Self and Society. Edited by E. Bruner. New York: American Ethnological Society, pp. 19–55. [Google Scholar]

- Beavert, Virginia. 1996. Origin of Basket Weaving. Journal of Women Studies 17: 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavert, Virginia, Michelle M. Jacob, and Joana W. Jansen. 2021. Anakú Iwachá: Yakama Legends and Stories. Seattle: The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, in association with the University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beavert, Virginia R. 2017. The Gift of Knowledge = Ttnúwit Átawish Nch’inch’imamí: Refelctions on Sahaptin Ways. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, Johnny, Marie-Hélène Canapé, Sébastien Lamarre-Tellier, Alicia Ibarra-Lemay, and Natasha Blanchet-Cohen. 2023. “Community Envelops Us in This Grey Landscape of Obstacles and Allows Space for Healing”: The Perspectives of Indigenous Youth on Well-Being. Genealogy 7: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajete, Gregory A. 2015. Indigenous Community: Rekindling the Teachings of the Seventh Fire. St. Paul: Living Justice Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, Gregory A. 2017. Children, myth and storytelling: An Indigenous perspective. Global Studies of Childhood 7: 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, Pat, and Abigail Bray. 2019. Indigenous relationality: Women, kinship and the law. Genealogy 3: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, Janice. 2005. Telling stories to the seventh generation: Resisting the assimilationist narrative of stiya. In Reading Native American Women: Critical/Creative Representations. Edited by Ines Hernandez-Avila. Lanham: AltaMira Press, pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ikpo, David. 2023. Advancing Queer-inclusive International Human Rights Law Education in Nigerian Classrooms though Indigenous Storytelling: Stories from a Law Classroom at Eko (Lagos, Nigeria). The Australian Feminist Law Journal 49: 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, Michelle M. 2013. Yakama Rising: Indigenous Cultural Revitalization, Activism, and Healing. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, Michelle M. 2021. Fox Doesn’t Wear a Watch: Lessons from Mother Nature’s Classroom. Whitefish: Anahuy Mentoring, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach, Margaret. 2018. A story in the telling. Learning Landscapes 11: 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minthorn, Robin Zape-tah-hol-ah, Michelle Montgomery, and Denise Bill. 2021. Reclaiming Emotions: Re-Unlearning and Re-Learning Discourses of Healing in a Tribally Placed Doctoral Cohort. Genealogy 5: 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitras Pratt, Yvonne. 2019. Digital Storytelling in Indigenous Education: A Decolonizing Journey for a Métis Community, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameka, Lesley K. 2021. Kaupapa Māori assessment: Reclaiming, reframing and realising Māori ways of knowing and being within early childhood education assessment theory and practice. Frontiers in Education (Lausanne) 6: 687601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigsby, Bruce. 2009. The origin and history of the name “Sahaptin”. In Ichishkíin Sínwit: Yakama/Yakima Sahaptin Dictionary. Edited by V. Beavert and S. Hargus. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. xviii–xxi. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Leanne B. 2017. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stiegman, Martha, and Sherry Pictou. 2023. We story the land: Exploring Mi’kmag food sovereignty, Indigenous law and treaty relations. The Journal of Peasant Studies 51: 1–24, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutterlict, Gregory. 2022. MIIMAWÍT: Our Ways, Our Language, Our Children, Our Land. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Helen. 2022. Restorative justice does more than solve conflict. It helps build classroom community. EdSurge. February. Available online: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2022-02-23-restorative-justice-does-more-than-solve-conflict-it-helps-build-classroom-community (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Tynan, Lauren. 2021. What is relationality? Indigenous knowledge practices and responsibilities with kin. Cultural Geographies 28: 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weuffen, Sara, Fred Cahir, Alice Barnes, and Bryon Powell. 2019. Uncovering hidden histories: Evaluating preservice teachers’ (pst) understanding of local Indigenous perspectives in history via digital storytelling at Australia’s sovereign hill. Diaspora, Indigenous and Minority Education 13: 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, Levina. 2008. Nine virtues of the Yakima Nation. Democracy & Education 17: 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Windchief, Sweeney, and Kenneth E. Ryan. 2019. The sharing of indigenous knowledge through academic means by implementing self-reflection and story. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 15: 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).