Like Water, We Re-Member: A Conceptual Model of Identity (Re)formation through Cultural Reclamation for Indigenous Peoples of Mexico in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Invocation

1.2. Re-Membering Indigenous Identities

I write to remember.I make rite (ceremony) to remember.It is my right to remember.

It is a colonial legacy to forget, and it is a response to trauma to have gaps in memory; conversely, it is a practice of decolonization and healing to remember. This is not an easy or linear path to walk.(p. 17)

The way that we are born… is crucial, and we need to also remember that because we’re carried with water, we’re in water, and that water is a transmitter of emotions… Everything that we say, everything that is, is able to [resonate] in our womb… Generational trauma has been passed on… And the womb, carries the memories of that.(Yoloteotl)

2. Literature Review

2.1. Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Identity

2.2. Towards a New Model of Identity (Re)formation

3. Methods

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Conceptual Model Development and Data Analysis

3.2.1. Data Immersion

Water runs through our human veins and connects us to everything. The water we drink is the water the salmon breathes, is the water the trees need, is the water where the Bear bathes, is the water where the rocks settle. Many of our stories foreground relationships to water. These stories show us that water is theory; theory that is built from relationships to the land, the earth, everything.(p. 1)

3.2.2. Case Analysis

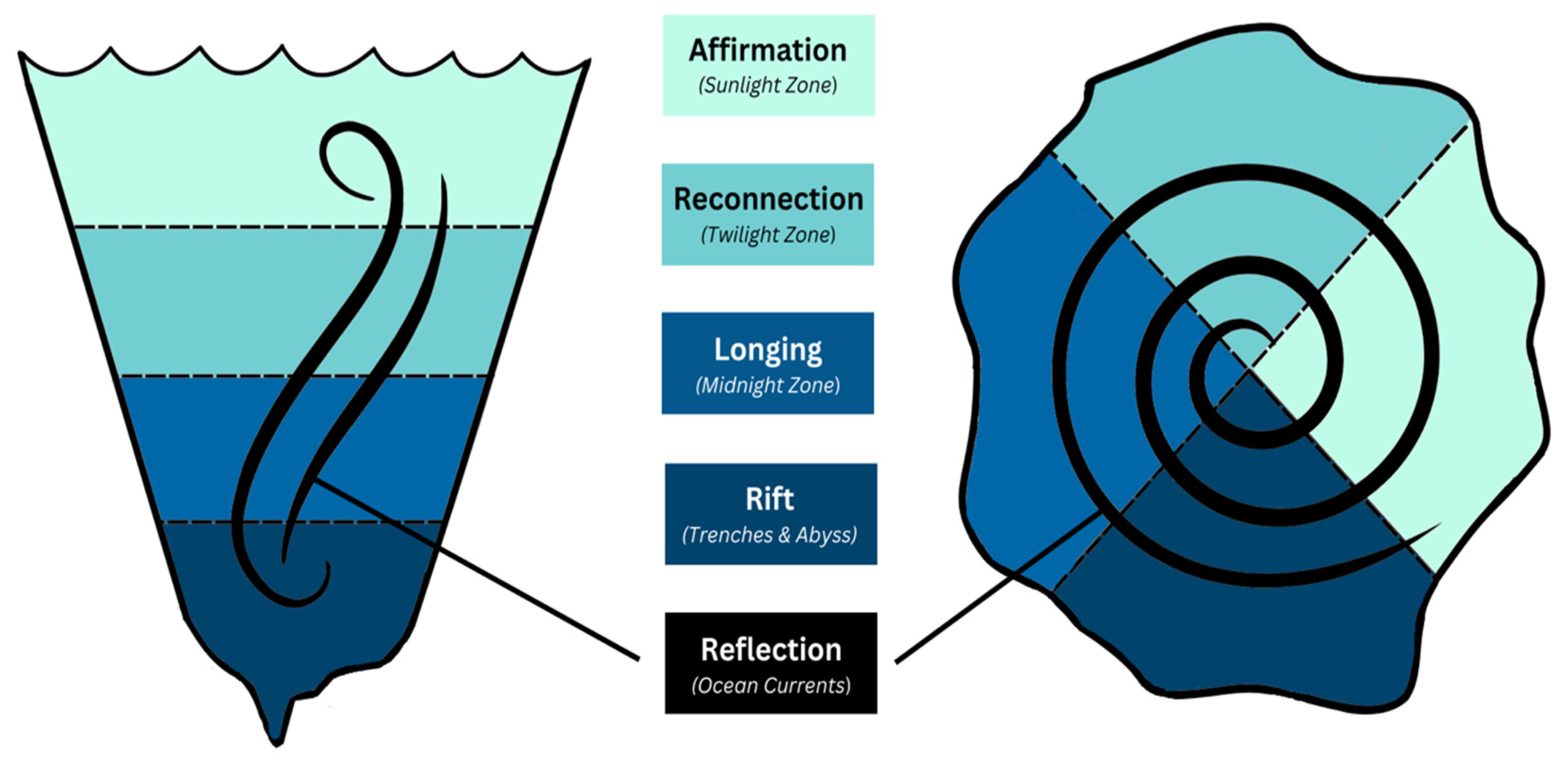

4. A Conceptual Model of Identity Reclamation

4.1. Reflection—Ocean Currents

4.2. Rift—Trenches and Abyss

4.3. Longing—Midnight Zone

4.4. Reconnecting—Twilight Zone

4.5. Affirmation—Sunlight Zone

5. Case Narratives

5.1. Bonifacio

5.1.1. Rift

5.1.2. Longing

… I can’t be a Mixteco or Ñuu Savi here because I’m not in my village. Or I can’t be Mexicano here because I’m not Mexicano. I can’t be white because I don’t look like white. All these identities mix you, it messes up who you want to be and it’s hard for you to choose what you want to be.

5.1.3. Reconnecting

5.1.4. Affirmation

Even though [mole] is hot, even though…it burns your mouth, you still want to eat more and more… At the end of the day, if you keep eating it, it feels good. I like that feeling. I think for us [Indigenous people in this country], we get all this racism [and] prejudice, we still want to keep our Indigenous [ways of life] alive. It makes us more be, want to be part of that, right?… We have to keep the fire on or else if it’s, if it’s out, who’s going to be able to see again and turn it back on, right?

5.2. Olga

5.2.1. Rift

5.2.2. Longing

The land we walk upon [is] our original land. I think it’s the land before borders were placed before countries were named, before territories were seized by force. I think we belong to this land. It’s not about ownership like we own it or this is our land, but rather we are of this land.

5.2.3. Reconnecting

So then I went to, in college, I was Chicana, right? As an activist. And then wanting to honor that history and the reality of how I grew up. And then eventually again, learning more about who we were as [Yaqui and Otomí] people and claiming that as well.

It’s just putting us on this path of understanding what names mean and the power of that and community… And it was just the most beautiful experience. It was at night. We’d buried the placenta by a tree as, as is part of our tradition so that the tree grows strong and our children can grow strong with it.

5.2.4. Affirmation

So I want to spend…the rest of my time finding joy in the work that I do in community, finding joy through the healing that I’m able to bring to myself and those around me. I owe it to them and to myself and to my future generations to understand what that looks like for me and to just live in a place of joy.

I want my legacy to be that we are Indigenous people, that we are unapologetic about that, that we’re very proud that this is our homeland and that we’ve always been here and that will always continue to be here. And I want them to walk with that knowledge, you know, feeling just so connected to their identity and to who they are and that no one can define them but themselves.

5.3. Yoloteotl

5.3.1. Rift

5.3.2. Longing

5.3.3. Reconnecting

5.3.4. Affirmation

Being able to continue to heal, to learn, to adapt the education, and the notes that I’m acquiring through the educational system… to create change into the systems of oppression, to help our Indigenous communities to thrive.

6. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We use this spelling of “re-membering” to describe the process of both remembering cultural knowledge and re-membering in the sense of putting back together in a way that reflects the integration of traditional Indigenous knowledge with one’s identity. |

| 2 | We are using the term “co-researchers” to indicate that participating community members were not only part of sharing their stories as data but were also actively involved in the design, development, implementation, and ongoing oversight of our project. As scholars committed to Indigenist research, we actively seek to disrupt the hierarchical and extractive nature of research. We believe this term better identifies their roles as collaborators and conspirators in the liberatory aims of our project. |

| 3 | While not all diasporic Indigenous peoples from Latin America residing in the U.S. identify as Latinx, we are using this term because Latinx is the broadest category/pan-ethnic category most commonly used to refer to people from Latin America. |

| 4 | While our model reflects many qualities of the ocean, in particular the layers of the ocean, we are making this connection through metaphor and not with literal parallels to the ocean layers in their myriad complexity. |

| 5 | The cholo lifestyle to which Bonifacio refers marks a distinct subculture that has been described as having characteristics such as “defiant individualism,” carnalismo (brotherhood), and machismo which some youth may adopt as a way to form a community when dominant society continuously marginalizes them (Valdez 2003). |

References

- Aikenhead, Glen S., and Masakata Ogawa. 2007. Indigenous Knowledge and Science Revisited. Cultural Studies of Science Education 2: 539–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, Lourdes. 2017. Coming Out as Indian: On Being an Indigenous Latina in the US. Latino Studies 15: 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, Jo-Ann. 2008. Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. 2013. Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy. Feminist Formations 25: 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillas Chón, David W. 2010. Oaxaqueño/a students’(un) welcoming high school experiences. Journal of Latinos and Education 9: 303–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillas Chón, David W. 2021. When children of Tecum and the Quetzal travel north: Cultivating spaces for their survival. Educational Studies 57: 287–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillas Chón, David W., Pablo D. Montes, and Judith Landeros. 2021. Indigenous Latinxs and Education. In Handbook of Latinos and Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, Ramona. 2023. Our stories are our medicine. Brief and Brilliant talk. Paper presented at Society for Social Work Research Annual Conference, Phoenix, AZ, USA, January 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, Ramona, Antonia R. G. Alvarez, and Angela Fernandez. 2023. “I see myself strong”: A description of an expressive poetic method to amplify Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer Indigenous youth experiences in a culture-centered HIV prevention curriculum. Geneaology 7: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, Ramona, Antonia R. G. Alvarez, Lisa Colón, Xochilt Alamillo, and Annie Zean Dunbar. 2020. La cultura cura: An exploration of enculturation factors in a community-based culture-centered HIV prevention curriculum for Indigenous youth. Genealogy 4: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, Ramona, Katie Schultz, Angela Fernandez, Karina Walters, Bonnie Duran, and Tessa Evans-Campbell. 2018. From ambivalence to revitalization: Negotiating cardiovascular health behaviors related to environmental and historical trauma in a Northwest American Indian community. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research (Online) 25: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, Melanie, Ysanne Chapman, and Karen Francis. 2008. Memoing in Qualitative Research: Probing Data and Processes. Journal of Research in Nursing 13: 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, Maylei, Floridalma Boj Lopez, and Luis Urrieta. 2017. Special Issue: Critical Latinx Indigeneities. Latino Studies 15: 126–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, Beth. 1994. Writing as Witness: Essay and Talk. London: Women’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caminero-Santangelo, Marta. 2004. “Jasón’s Indian”: Mexican Americans and the Denial of Indigenous Ethnicity in Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima. Critique-Studies in Contemporary Fiction 45: 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, Saskias, Brendan O’Connor, and Vanessa Anthony-Stevens. 2016. Ecologies of adaptation for Mexican Indigenous im/migrant children and families in the United States: Implications for Latino studies. Latino Studies 14: 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Kris, and Michael Yellow Bird. 2021. Decolonizing Pathways towards Integrative Healing in Social Work, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Russell, and Yacob Reyes. 2021. Number of U.S. Latinos Identifying as Multiracial Skyrockets 567% as Census Gives More Options. Axios. August 19. Available online: https://www.axios.com/2021/08/19/multiracial-identity-us-latinos-black-indigenous (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Cotera, María E., and María J. Saldaña-Portillo. 2014. Indigenous but Not Indian?: Chicana/Os and the Politics of Indigeneity. In The World of Indigenous North America. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Denham, Diana. 2023. Interpreting Spatial Struggles in the Historical Record: Indigenous Urbanism and Erasure in 20th-Century Mexico. Environment and Planning F 2: 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, Grace L. 2016. Indigenous Futurisms, Bimaashi Biidaas Mose, Flying and Walking towards You. Extrapolation 57: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Campbell, Teresa. 2008. Historical Trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska Communities: A Multilevel Framework for Exploring Impacts on Individuals, Families, and Communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23: 316–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, Angela. 2019. “Wherever I Go, I Have It Inside of Me”: Indigenous Cultural Dance as a Transformative Place of Health and Prevention for Members of an Urban Danza Mexica Community. Available online: https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/44630 (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Fernandez, Angela, and Ramona Beltrán. 2022. “Wherever I Go, I Have It Inside of Me”: Indigenous Cultural Dance Narratives as Substance Abuse and HIV Prevention in an Urban Danza Mexica Community. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 789865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, Sprague Ian. 2016. Clarifying Limbo: Disentangling Indigenous Autonomy from the Mexican Constitutional Order. Perspectives on Federalism 8: 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Forman, Jane, and Laura Damschroder. 2007. Qualitative Content Analysis. In Empirical Methods for Bioethics: A Primer. Edited by Liva Jacoby and Laura A. Siminoff. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 11, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Heather, and Dee Michell. 2015. Feminist Memory Work in Action: Method and Practicalities. Qualitative Social Work 14: 321–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, Suzanne Newman. 2019. Introduction: Indigenous Futurisms in the Hyperpresent Now. World Art 9: 107–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, Tom S. 2012. Oceanography: An Invitation to Marine Science. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- George, Rachel Yacaaʔał, and Sarah Marie Wiebe. 2020. Fluid Decolonial Futures: Water as a Life, Ocean Citizenship and Seascape Relationality. New Political Science 42: 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gone, Joseph P. 2011. The Red Road to Wellness: Cultural Reclamation in a Native First Nations Community Treatment Center. American Journal of Community Psychology 47: 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Elizabeth. 2018. Ethnoracial Attitudes and Identity-Salient Experiences Among Indigenous Mexican Adolescents and Emerging Adults. Emerging Adulthood 7: 216769681880533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, Sandy. 2015. Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Julie, Karen Willis, Emma Hughes, Rhonda Small, Nicky Welch, Lisa Gibbs, and Jeanne Daly. 2007. Generating Best Evidence from Qualitative Research: The Role of Data Analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 31: 545–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heart, Maria Yellow Horse Brave, and Josephine Chase. 2016. Historical Trauma Among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: Concepts, Research, and Clinical Considerations. In Wounds of History. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Ávila, Inés. 1995. Relocations upon Relocations: Home, Language, and Native American Women’s Writings. American Indian Quarterly 19: 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, Catherine, Kathy Murphy, David Shaw, and Dympna Casey. 2014. Qualitative Case Study Data Analysis: An Example from Practice. Nurse Researcher 22: 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Anita, Paula Lusardi, Donna Zucker, Cynthia Jacelon, and Genevieve Chandler. 2002. Making Meaning: The Creative Component in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Health Research 12: 388–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseke, Judy M. 2014. Indigenous Digital Storytelling in Video: Witnessing with Alma Desjarlais 1. In Social Justice and the Arts. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kidman, Joanna, Liana MacDonald, Hine Funaki, Adreanne Ormond, Pine Southon, and Huia Tomlins-Jahnkne. 2021. “Native Time” in the White City: Indigenous Youth Temporalities in Settler-Colonial Space. Children’s Geographies 19: 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovats Sánchez, Gabriela. 2020. Reaffirming Indigenous Identity: Understanding Experiences of Stigmatization and Marginalization among Mexican Indigenous College Students. Journal of Latinos and Education 19: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrner, Amy, and Rachel Yehuda. 2018. Cultural Trauma and Epigenetic Inheritance. Development and Psychopathology 30: 1763–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leza, Christina. 2019. Divided Peoples: Policy, Activism, and Indigenous Identities on the U.S.-Mexico Border. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Jana P., and Anne Brunet. 2013. Bridging the Transgenerational Gap with Epigenetic Memory. Trends in Genetics 29: 176–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linneberg, Mai Skjott, and Steffen Korsgaard. 2019. Coding Qualitative Data: A Synthesis Guiding the Novice. Qualitative Research Journal 19: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Caballero, Paula. 2021. Inhabiting Identities: On the Elusive Quality of Indigenous Identity in Mexico. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 26: 124–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado-Casas, Margarita. 2012. Pedagogías Del Camaleón/Pedagogies of the Chameleon: Identity and Strategies of Survival for Transnational Indigenous Latino Immigrants in the US South. The Urban Review 44: 534–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masotti, Paul, John Dennem, Karina Bañuelos, Cheyenne Seneca, Gloryanna Valerio-Leonce, Christina Tlatilpa Inong, and Janet King. 2023. The Culture Is Prevention Project: Measuring Cultural Connectedness and Providing Evidence That Culture Is a Social Determinant of Health for Native Americans. BMC Public Health 23: 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiydzenyuy, Ngala Elvis, Sian Megan Joanna Hemmings, and Lihle Qulu. 2022. Prenatal Maternal Stress and Offspring Aggressive Behavior: Intergenerational and Transgenerational Inheritance. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 16: 977416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, Kate, Eve Tuck, and Marcia McKenzie. 2017. Land Education: Rethinking Pedagogies of Place from Indigenous, Postcolonial, and Decolonizing Perspectives. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, Dwanna L. 2021. Real Indians: Policing or Protecting Authentic Indigenous Identity? Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 7: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Matthew B., and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Moraga, Cherríe L. 2011. A Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness: Writings, 2000–2010. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Figueroa, Mónica G. 2010. Distributed Intensities: Whiteness, Mestizaje and the Logics of Mexican Racism. Ethnicities 10: 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, Federico. 2016. México Racista: Una Denuncia. How Mexico Uses Mestizaje for Indigenous Erasure. Ciudad de Mexico: Grijalbo. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, Brenda. 2021. “Soy de Zoochina”: Transborder Comunalidad Practices among Adult Children of Indigenous Migrants. Latino Studies 19: 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, Bethan C., and Callum M. Roberts. 2018. Ecological Connectivity across Ocean Depths: Implications for Protected Area Design. Global Ecology and Conservation 15: e00431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Figueroa, Araceli. 2021. The Historical Trauma and Resilience of Individuals of Mexican Ancestry in the United States: A Scoping Literature Review and Emerging Conceptual Framework. Genealogy 5: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Williams, Anna, Ramona Beltrán, Katie Schultz, Zuleka Ru-Glo Henderson, Lisa Colón, and Ciwang Teyra. 2021. An Integrated Historical Trauma and Posttraumatic Growth Framework: A Cross-Cultural Exploration. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 22: 220–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Cedric J. 2020. Black Marxism, Revised and Updated Third Edition: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Aimee Carrillo, and Eve Tuck. 2017. Settler Colonialism and Cultural Studies: Ongoing Settlement, Cultural Production, and Resistance. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 17: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, Johnny. 2021. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña-Portillo, María Josefina. 2017. Critical Latinx Indigeneities: A Paradigm Drift. Latino Studies 15: 138–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, Jason, and John Gerring. 2008. Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. Political Research Quarterly 61: 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. 2014. Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg Intelligence and Rebellious Transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sotero, Michelle M. 2006. A Conceptual Model of Historical Trauma: Implications for Public Health Practice and Research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 1: 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stavenhagen, Rodolfo. 2015. Ruta Mixteca: Indigenous Rights and Mexico’s Plunge into Globalization. Latin American Perspectives 42: 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Eve. 2009. Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. Harvard Educational Review 79: 409–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. 2012. Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1: 1. [Google Scholar]

- United Mexican States. 2015. Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. Article II. §4. Mexico: United Mexican States. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country. In Census.Gov. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Valdez, Avelardo. 2003. 2. Toward a Typology of Contemporary Mexican American Youth Gangs: Alternative Perspectives. In Gangs and Society: Alternative Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valdovinos, Miriam, Ramona Beltrán, Antonia R. G. Alvarez, Annie Zean Dunbar, and Debora Ortega Debora. 2022. Our stories are our medicine. Paper presented at the Council of Social Work Education Annual Public Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, November 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Veracini, Lorenzo. 2011. Telling the End of the Settler Colonial Story. In Studies in Settler Colonialism: Politics, Identity and Culture. Edited by Fiona Bateman and Lionel Pilkington. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 204–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizenor, Gerald. 2008. Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Karina L., and Jane M. Simoni. 2002. Reconceptualizing Native Women’s Health: An “Indigenist” Stress-Coping Model. American Journal of Public Health 92: 520–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Karina L., Selina A. Mohammed, Teresa Evans-Campbell, Ramona Beltrán, David H. Chae, and Bonnie Duran. 2011. Bodies Don’t Just Tell Stories, They Tell Histories: Embodiment of Historical Trauma among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 8: 179–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, Lisa Johnson. 2011. Beliefs Associated with Mexican Immigrant Families’ Practice of La Cuarentena during Postpartum Recovery. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 40: 732–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Hilary N. 2001. Indigenous Identity: What Is It and Who Really Has It? The American Indian Quarterly 25: 240–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native. Journal of Genocide Research 8: 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. n.d. Ocean Zones. Available online: https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-zones/ (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Yazzie, Melanie, and Cutcha Risling Baldy. 2018. Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 7: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, Nagy A., Laura Lockwood, Shaoyong Su, Guang Hao, and Bart P. F. Rutten. 2018. The Effects of Trauma, with or without PTSD, on the Transgenerational DNA Methylation Alterations in Human Offsprings. Brain Sciences 8: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, Susy J. 2022. Queering Mesoamerican Diasporas: Remembering Xicana Indigena Ancestries. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

To, M.N.; Beltrán, R.; Dunbar, A.Z.; Valdovinos, M.G.; Pacheco, B.-A.; Barillas Chón, D.W.; Hunte, O.; Hulama, K. Like Water, We Re-Member: A Conceptual Model of Identity (Re)formation through Cultural Reclamation for Indigenous Peoples of Mexico in the United States. Genealogy 2023, 7, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7040090

To MN, Beltrán R, Dunbar AZ, Valdovinos MG, Pacheco B-A, Barillas Chón DW, Hunte O, Hulama K. Like Water, We Re-Member: A Conceptual Model of Identity (Re)formation through Cultural Reclamation for Indigenous Peoples of Mexico in the United States. Genealogy. 2023; 7(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleTo, My Ngoc, Ramona Beltrán, Annie Zean Dunbar, Miriam G. Valdovinos, Blanca-Azucena Pacheco, David W. Barillas Chón, Olivia Hunte, and Kristina Hulama. 2023. "Like Water, We Re-Member: A Conceptual Model of Identity (Re)formation through Cultural Reclamation for Indigenous Peoples of Mexico in the United States" Genealogy 7, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7040090

APA StyleTo, M. N., Beltrán, R., Dunbar, A. Z., Valdovinos, M. G., Pacheco, B.-A., Barillas Chón, D. W., Hunte, O., & Hulama, K. (2023). Like Water, We Re-Member: A Conceptual Model of Identity (Re)formation through Cultural Reclamation for Indigenous Peoples of Mexico in the United States. Genealogy, 7(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7040090