1. Introduction

Underpinned by Kaupapa Māori, one of the key aims of the Marae Ora, Kāinga Ora (MOKO) project is to enable marae to utilise findings of this research to develop sustainable marae-led kāinga initiatives with their communities. In addition, this research will provide insights and opportunities to achieve greater outcomes and collective advantages for whānau and community wellbeing, which includes opportunities to be involved in collaborative future-thinking housing development in and around marae.

Marae are traditional places of gathering known across Polynesia as culturally significant communal spaces. In Aotearoa, marae are physical manifestations of identity and belonging for Māori. In tribal settings, marae represent common ancestral connections and whakapapa (genealogical) relationships. In this article, the progressive nature of marae in a modern context and in an urban setting highlights the agility of marae to adapt to changing environments. Marae are recognised as key knowledge holders of Māori culture and, consequently, are invaluable contributors to the wellbeing of Māori.

The genesis for the MOKO research project emerged following research undertaken in partnering with Te Puea Memorial Marae (

Lee-Morgan et al. 2017). Te Puea Memorial Marae (TPMM) is located in the high-density urban environment of Māngere in South Auckland. During 2016/17, in the tradition of manaakitanga (caring for) and the legacy of Te Puea Herangi, the marae successfully increased their social service provider capacity in response to the increased number of families coming to them for relief, support and advocacy needs concerning unsafe and inadequate living circumstances (

Lee-Morgan et al. 2017). This research initiative documented the experience of the marae who actively intervened in providing relief for homeless whānau in Tāmaki Makaurau through their marae-based Manaaki Tangata (caring for, hosting people) Homeless Programme (

Lee-Morgan et al. 2019;

Dennis 2019).

According to the 2018 Census, the Māori population in Tāmaki Makaurau was 11.5%. However, Māori were starkly over-represented as 43% of the homeless in Tāmaki Makaurau in 2019 (cited in

Independent Māori Statutory Board 2020). The housing deprivation and homelessness statistics for Māori in Tāmaki Makaurau paint a bleak picture that is not uncharacteristic of the rest of Aotearoa:

Over 11,700 Māori are currently experiencing severe housing deprivation (

Amore et al. 2013);

An estimated 1290 Māori were homeless, with 235 in emergency housing, 1056 in commercial accommodation or living temporarily on marae and 9149 living in severely overcrowded homes (

Amore et al. 2013);

A further 22,184 Māori received an income-related rent subsidy as Housing New Zealand clients (they constituted 34.5% of all recipients (

Amore et al. 2013));

A total of 28.2% of Māori were living in owner-occupied homes, compared to the national average of 49.8% (

Stats NZ 2013).

Kake (

2019) reflected on the combined negative statistics that continue to impact Māori and scream for attention. Subsequently, the pressure to adequately accommodate Māori has generated growing expectations on state social service sector as well as the different provider entities, including marae, to be accessible and offer practical support to struggling whānau. As researchers involved in reporting the positive outcomes from Te Puea Memorial Marae’s intervention, the insights informed a decision to expand on the potential for more marae to be supported to explore their own capability in this space.

The MOKO project posed two critical questions to guide the activity each marae would be investigating with regard to this exercise of reimagining kāinga:

How can marae best utilise their physical, economic, social and cultural capital and infrastructure in their provision of housing interventions as kāinga Māori?

How can iwi, hapū, communities, service providers and agencies best collaborate with marae to ensure the successful creation of kāinga to support resilient whānau in South Auckland?

The role of marae in the Tāmaki Makaurau housing crisis (

Lee-Morgan et al. 2017,

2019) revealed the success of marae in responding to community needs, including housing interventions. This illustrates the desire and capacity of marae to provide a range of marae-led initiatives for the purpose of increasing whānau wellbeing (

Kawharu 2014;

Tapsell 2002). Marae provides a sociocultural setting for Māori and “a place in which Māori customs are given ultimate expression” (

Tauroa and Tauroa 2009, p. 6). In the contemporary urban environment of South Auckland, marae continue to hold this space and function for Māori. Over the 2020–2022 period, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated a far-reaching response from essential services to assist whole communities in need, including those without accommodation. What became evident during the enforced lockdowns was the active leadership shown by Māori to mobilise support within their own networks and with the restricted resources available to them.

The vital work of marae as outreach services during the pandemic in providing food, medical care, protective equipment, social support, and information to whole communities, not just for Māori, is seen as an example of an effective holistic response, not only in Aotearoa but at an international level (

Te One and Clifford 2021).

In the past two years, the MOKO project has supported a forum for the marae-based researchers employed with each of the five marae involved in the project. This created a space for MRCs to collectively share their individual experiences and observations and to regularly discuss the issues, both unique and common, which the marae individually and collectively encountered during the pandemic crisis. Each marae has been engaged with their local communities in different ways to offer support relative to their capability. While the priority during the COVID-19 lockdowns was to provide immediate relief for those most vulnerable in the community, the initial impetus for the MOKO project was to test the interest and viability of marae to develop their own vision around housing support for whānau. Remarkably, this was still able to be progressed. The MOKO research project therefore set about investigating the potential of the five marae to strengthen their provision of kāinga in the contemporary urban context of South Auckland.

The MOKO project is shaped by the theoretical underpinnings of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) (

Israel et al. 2010) and Kaupapa Māori (KM) (

Pihama et al. 2004,

2015;

Smith 1997,

1999). Both research methodologies advocate the importance of relationships and the respectful way in which information, knowledge and proficiency are shared. These were chosen as approaches that would best support the opportunity to undertake research by, for and with marae and communities to contribute to the strategic and collective development of kāinga ora (housing wellbeing) for whānau and community. The project facilitated a research partnership that prioritised the principle of collaboration and transformative outcomes for the collective. This required an investment of regular weekly contact in the first year of the project to build trust, develop respect and value the different strengths and skills across the research team. Knowledge creation was experienced as the team learned more about the research itself and gained insights into their own working knowledge around marae development. The sharing of knowledge became about respecting the different marae identities, appreciating the thinking space to view commonalities and the growth of confidence in a safe place to critique and engage in collective solution-seeking. All of these aspects built a high-trust leadership model within the project. Central to the MOKO methodology was maintaining the pedagogy of interaction between the marae and the research entity were culturally relevant and driven by their own health and wellbeing aspirations.

As a KM study, there are multiple layers and dimensions to the research experience. It has been critical to ensure that all the marae have been equally responsible for achieving all expectations of the research, including participation, engagement, collaboration, analysis and success (

Smith 1997); this is made possible through high-trust relationships between the MRCs and their marae communities. CBPR safeguards and ensures marae and community are central to all dimensions of the research.

Historical Context

The kāinga is distinctive to ensuring Māori ways of living; historically, this meant living in collective ways and shared spaces with shared responsibilities. Ancestral kāinga were connected through tribal narratives to the natural environment, located close to seasonal food sources, and founded on cultural knowledge systems that ensured the ongoing connection of people to their land and waterways (

Awatere et al. 2008). Traditionally situated in close proximity to the marae, kāinga housed kinship groups that populated the marae, providing a kaitiaki role in attending to everyday activities and the cultural duties of Tikanga/Māori law (

Kake 2015).

Kia mā te marae, hurihia te pōhatu; whai iho mā te ahi kā ki te marae e whakaatu.

A clean marae with no fires burning is worthless, but one supported by people and their cooking fires is of high value.

This whakataukī (proverb) refers to the importance of the warmth of people required to keep the marae space alive and ensure the ongoing transference of cultural knowledge to future generations as a necessary symbiotic relationship. The marae is the heart of the kāinga and provides cultural sustenance. The presence of burning fires relays that the marae is active and is therefore nourishing the people; the role of those that keep the fires burning is to occupy the lands for current and future generations (

Metge 2013).

The view of kāinga as a place of belonging and home rather than a purely physical shelter is common among other Indigenous peoples, who recognise land as a living entity that signifies a bond, relationship and love of the land (

Saha et al. 2019). Professor Manuka Henare, in an interview with He Tohu, provides an expression of this in his interpretation of the wording in 1835 He Wakaputanga Declaration of Independence, where the phrase “ko mātou te mana i te whenua” is used. Henare suggests that it means “we can speak, because we have the mana that comes from the land to us” (

He Tohu 2019). This is used to state the position of the Tangata Whenua (Māori, people of the land) as the Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa, thus reinforcing Indigenous concepts associated with the land and the understanding that Indigenous identities lie in the land.

The earliest reference that speaks to the significance of kāinga as a critical component of the Māori societal structure is in Article 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Ko te Kuini ō Ingarani ka wakarite ka whakaae ki ngā Rangatira ki ngā hapū- ki ngā tangata katoa ō Nu Tirani te tino rangatiratanga ō rātou wenua, ō rātou kāinga me ō rātou taonga katoa (Facsimilies of the Declaration of Independence and Treaty of Waitangi, quoted in

O’Malley et al. 2010, p. 38).

The Queen of England agrees to protect the chiefs, the subtribes and all the people of New Zealand in the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures (

Wilson 2016).

Māori were guaranteed ‘tino rangatiratanga’ over, ō rātou whenua (our lands), ō rātou kāinga (our villages), ō rātou taonga katoa (our property and treasures), as stated in the article text above (

O’Malley et al. 2010, p. 38). Just as whānau are the primary social unit in Māori society, kāinga were the places where whānau lived and flourished. As

Durie (

2019) reiterates: “A kāinga embodies a house or a group of houses built around cultural values that connect with Tikanga Māori (cultural protocols), with the land on kāinga stand, with whānau and local communities” (p. 57).

The history of colonisation in Aotearoa in the form of land confiscation, illicit land acquisition, diminished Māori land tenure and restrictive controls over Māori land development has affected Māori land ownership and resulted in inequitable access to housing options (

Paul et al. 2020). This has undoubtedly contributed to the health and wellbeing disparities experienced by Māori and homelessness in the current housing crisis (

Smiler 2020;

Dennis 2019;

Henry and Crothers 2019;

Groot et al. 2011). The dispossession of land, alongside the severance of whānau from kāinga, where notions of secure identity, connection and belonging have been eroded on many different levels for Māori and have resulted in varying degrees of intergenerational grief, detachment and trauma (

Tapsell 2021). In a claim to The Waitangi Tribunal Office for Treaty Settlements, the Housing Policy and Services Inquiry (Wai 2750) has made a claim concerning housing policy and government services that have negatively affected whānau, hapū and iwi. This inquiry alleges that the Crown has not met the needs of Māori by providing adequate housing (

Waitangi Tribunal 2019). The steady and increasing number of Māori that have inadequate housing is indicative of the extent of Māori housing deprivation today (

Independent Māori Statutory Board 2020).

Reflecting on the historical context of the deliberate and conscious use of legislation to deconstruct and destabilise the cornerstones of Māori culture by successive governments (

Palmer 2019), the rejuvenation of marae and kāinga in a contemporary urban setting can be viewed as a welcomed response and assertion of Tino Rangatiratanga (self-determination, authority). As cited in

Haami (

2018):

While many urban Māori had lost their back-home connection during the 1960s and 1970s, the first wave of Māori migrants to the city were never completely detribalised but “adapted their tribal outlooks to the urban environment”.

Urban-dwelling Māori populations have sought to remedy the reconfiguration of ‘places of belonging’ by establishing marae in the urban setting. In South Auckland, this started in the 1980s (

Haami 2018). The five marae in the MOKO project reflect the diversity of marae in the South Auckland landscape; one kāinga settlement has been continuously occupied as a mana whenua (power, authority, original occupants) marae for the past 800 years, another is a taurā-here (tribal kinship groupings with links to other geographic locations) marae founded by descendants of Ngāti Awa, and the remaining three are pan-tribal mātaawaka urban marae (urban kinship groups from various places). This strengthens the idea that marae are vital conduits of cultural wellbeing, no matter what kind of legal entity status they are bound by. The role of the marae is more prominent than ever in the urban environment, connecting people to places and highlighting the importance of whakapapa in maintaining identity in the knowledge that these connections are critical to identity and belonging.

2. Results

In this section, we examined the aspirations for each marae and illustrate the diverse responses to housing provision put into action as opportunities throughout the MOKO project. The following narrative from each marae is based on a presentation delivered in December 2021 to the Unitec Research Symposium by each MRC. The Marae Researchers provide a considered commentary about their marae and the progress of priorities relevant to the housing provision and issues encountered to date.

2.1. Makaurau Marae–Pania Newton and Moana Waa (MRCs)

Ko Ihumātao te whenua houkura, ko te whenua taurikura ko te ūkaipō. We care for our peaceful and prosperous land at Ihumātao, which sustains us and teaches us that the wellbeing of the people is all intimately connected.

Makaurau Marae is situated in Ihumātao, within Māngere, and is known as the oldest continuously occupied village in Tāmaki Makaurau. In 1863, our Whenua was confiscated by the Crown, and many would say that this was the start of the displacement of our people.

From the unjust confiscation of our lands to the environmental degradation seen through industrial intensification, our people and Whenua have suffered significantly, and without a doubt, the landlessness created by the invasion in 1863 is at the heart of current issues that have come to public attention in recent times; that is, much of the impoverishment and homelessness experienced by our whānau today.

Despite over 150 years of being on the receiving end of some of the most draconian central and local government decisions seen in Aotearoa, our whānau of Ihumātao remain resilient and have aspirations to begin to heal the heartache of our past and to chart our own course. This includes reimagining our kāinga priorities that will see a better future for our tamariki and our mokopuna. Housing our most vulnerable whānau is a critical objective of ours and an enactment of our Kaitiakitanga (guardianship), Rangatiratanga (sovereign right, self-determination) and Mana Motuhake (authority).

Currently, there are approximately 87 homes within our papakāinga, and roughly about 80% of those homes are occupied by whānau who have ancestral connections to this land stretching over 1000 years since the arrival of our tūpuna (ancestors). This papakāinga, is illustrated in

Figure 1. Most of our whānau here live intergenerationally and are fortunate in the sense that they are only walking distance from their maunga (mountain), awa (river), marae (cultural centre), urupā (burial grounds, moana (sea)) and whānau (family).

Recently we had the opportunity to work with our whānau to reimagine what their own kāinga could look like. We were able to complete six kāinga feasibility studies, supported by Te Puni Kōkiri (The Ministry of Māori Development,) an opportunity to perform something different. These have ranged from tiny homes to mega-whare and small papakāinga builds within the papakāinga.

The process we undertook with whānau included developing a set of values that guided their vision and needs for their kāinga, and then we drew on these values to develop their master plans and concept designs. It has been a highlight to hear common themes across whānau, which include:

- -

Sustainability;

- -

Honouring the pūrākau and stories of the whenua and whānau;

- -

Upholding their mana motuhake and rangatiratanga.

These feasibility studies feed into a housing strategy that is supported by the wider MOKO whānau that is currently being developed by our marae whānau. This project is critical to enable our whānau to identify their needs, share our experiences and collectively voice our own housing needs. This includes being responsive to the needs of whānau, who have aspirations to return to the papakāinga to live, as well as ensuring that all residents within our papakāinga are living in safe, secure and healthy homes.

Recently, with the support of the MOKO project, we were granted some funding by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development to create a Housing Strategy for our hapū and marae. Through this process, we have been able to identify key priority areas to systematically support whānau into sustainable and mana-enhancing kāinga. We are currently in the process of applying to the He Taupae fund to support the implementation of the Kāinga Strategy by supporting further feasibility studies for whānau within our papakāinga.

When we reimagine our kāinga, we envisage kāinga that is led by whānau, for whānau; that is sustainable and sees the restoration of our lands, mana (authority), rangatiratanga (self-determination), taiao (environment), reo (language) and Tikanga (cultural protocols).

Makaurau Marae has embraced the opportunity to look into kāinga development through a strong foundation of engagement with the wider whānau and gaining a sense of refined direction by exploring a collective values base. This, along with access to specialist roles and targeted funding to progress their vision, is witnessed as a critical combination of essential factors to advance the initial steps for a kāinga project. As a mana whenua marae, their identity and intergenerational connection to the Whenua are firmly embedded. Despite recent struggles to secure their status about land ownership rights, connectivity is not an issue to Makaurau, as experienced by some of the other marae in the MOKO study.

2.2. Papatūānuku Kōkiri Marae–Hineamaru Ropati (MRC)

Kai he rongoā, Rongoā he Kai.

Our food is our medicine and our medicine is our food.

This whakataukī can be defined in so many ways, depending on the Kaupapa (purpose). We know for us it resonates through our experience that the purity and goodness of our food heal and nourishes our whānau, and what we share as a collective together, we find solutions (for) as a collective.

Papatūānuku Marae was established in 1986 to service the needs of urban Māori and whānau. Kaumātua (elder men) and kuia (elder women) from around the country living in Tāmaki Makaurau came to the realisation, alongside mana whenua and mātaawaka, that we needed to have a marae that would be able to service the needs of all the different tribal groups represented in the city.

The whānau at Papatūānuku can go back five or six generations as urban dwellers, coming from the country into the urban setting where they experienced some of their Tikanga and values being diluted over many years, generation after generation.

The development of a whare kāhui (housing cluster) was prioritised as the most recent need on the marae, brought to life by the prospects shared by whānau through a strategic planning and visioning exercise for the marae. Having a whare kāhui based at our marae allows whānau to come together to unite as whānau.

The moemoea (dream/aspiration) in regard to reimagining a kāinga was designed in collaboration with our Urban Intergenerational Kāinga Innovations project, funded by the National Science Challenge (NSC). The marae whānau express how lucky and privileged they are to have Design Tribe, and the MOKO research team supports the marae to explore this pathway. There were two key research questions that they set their planning baseline on:

What are the key contemporary kāinga innovations, and how can they respond and support Māori urban intergenerational housing aspirations and needs in Tāmaki?

How can marae-based whare kāhui be best designed to provide high quality, moderate cost, emergency transitional and long-term housing solutions for whānau?

A number of previous whānau generations moved to the urban setting in the early 1960s and 1970s and now have mokopuna (grandchildren) on top of mokopuna, illustrating that there is now a large generation of whānau that are enduringly continuing to live here in the city. Currently, the marae services whānau that are transitioning between accommodation or travelling from the north and needing a place to settle in temporarily. These whare kāhui allow them to be able to realign their pathways while they are living in an urban setting. Using the concept of maara (which is what the marae community actually undertake here at Papatūānuku Kōkiri marae, grow kai and teach others the same), these whānau are seeds. Like every seed, they need a number of supporting kaupapa around them to be able to grow.

For us to be able to build a whare kāhui, the marae needed to obtain some good tradespeople and support. This was confirmed as the first stage of the whare development by marae Trustees. Funding was needed to be able to pay for the design and consent, so this was sought and successfully funded by the National Science Challenge. Funding was also received from Foundation North to construct one unit, one whare. The NSC funding was able to cover resource consent costs for two whares.

Another idea about having the whare kāhui built in May 2021 was recognising that this is a prototype that could be rolled out to all marae around the motu (island), so they do not have to pay for an architect. Papatūānuku completed the checklist and followed the formal procedures for other marae to be able to follow suit and build similar structures around the motu. Hence, very much like seeds, the marae have been able to throw this example of a possible dwelling option up in the air for the concept to be enabled to grow in many other maara around the country. The second whare kāhui will be built in September 2022. Papatūānuku marae have progressed from the concept stage to the design and are now in the process of being built.

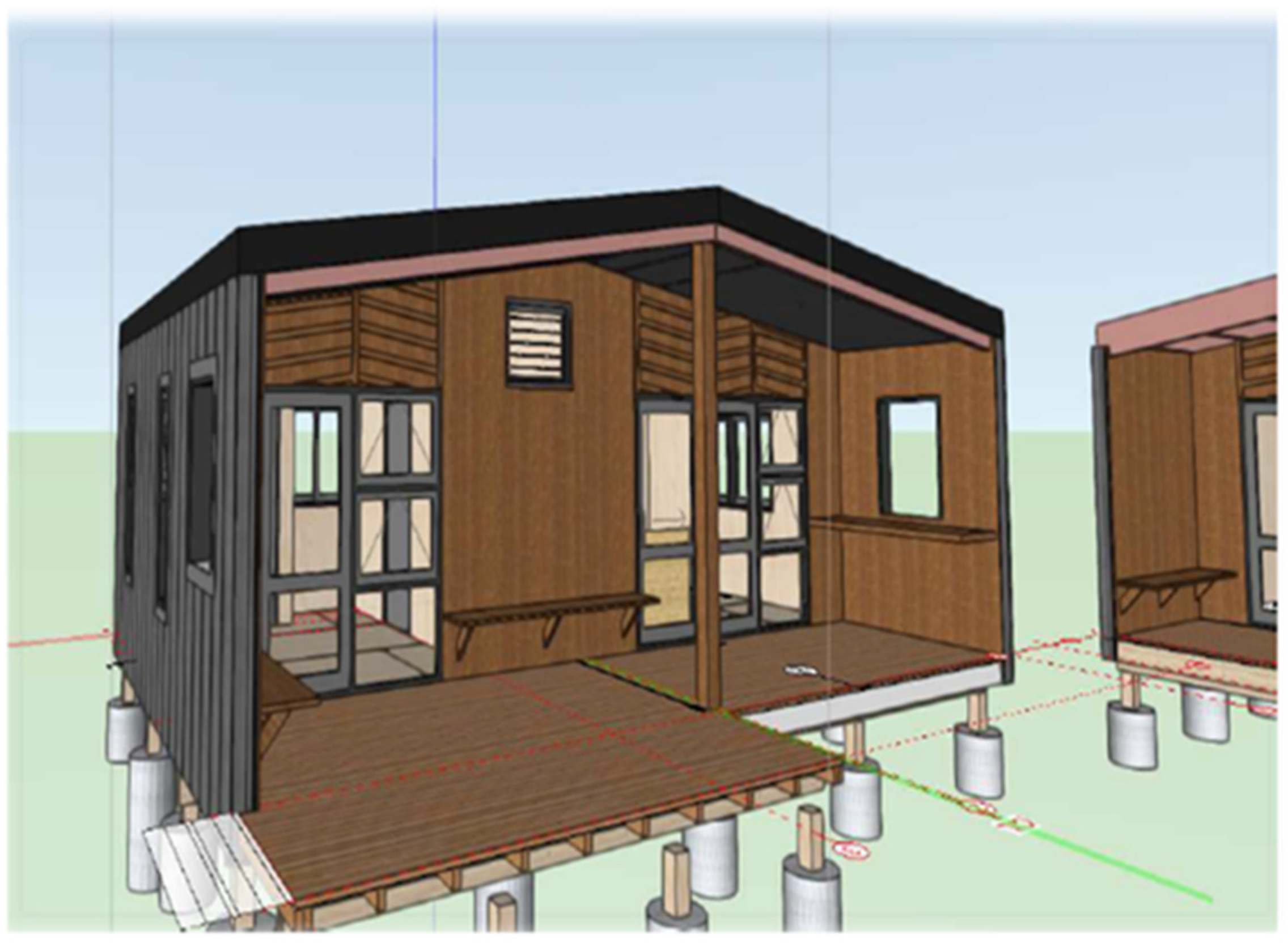

Figure 2 shows what the whare kāhui looks like as a kaupapa Māori tiny house. It was designed with consideration of the location of the wharepaku (toilet) and the kitchen. On any marae and in any whare, you want to ensure that these two parts of our wāhi tapu (sacred areas) in our whare are totally separated and in a convenient place in the design that is going to service the needs of manuhiri coming in and also those that live on the complex. It is a one-bedroom, self-contained kaupapa. It has a big māhau, or verandah, out the front so that whānau occupying the whare will be able to host and facilitate different workshops for wider whānau and join everything together. Nothing is ever singular; it is always combined with something else.

The whare kāhui is a place for short retreats for whānau needing time out to recharge their wairua (spirit) and give clarity to their pathway.

Here in South Auckland, or Tāmaki Makaurau, police frequently report domestic violence in homes and all sorts of challenges that are happening for whānau. These whare kāhui will be able to accommodate some time-out space for some. The vision is to provide a place also for kaumātua and kuia needing to come together for companionship and kōrero … me noho wānanga (a learning space), so that they can talk about things relevant to their world, (away from) the busyness of everything else.

Lastly, this is seen as a place of rongoā (medicine)—a retreat to heal and reflect. While homes for our whānau are a focus, there is an important drive to ensure that there is clarity and unity and that there is peace in the whare of each whānau, and their own independent wellbeing, as a wahine (woman), as a tāne (man) and as rangatahi (youth). Whare kāhui is our kāinga, set up to look after our whānau. The original intent for the creation of this marae continues at present to provide a safe space to live as Māori and exercise Tikanga (cultural protocols) and te reo (the language). However, the demand to meet the needs of whānau presenting with diverse needs has meant that Papatūānuku has needed to expand to provide a range of social supports to whānau.

Unfortunately, Papatūānuku Kōkiri Marae encountered a barrier at the eleventh hour, with an administrative cost factor from the local authority responsible for resource consent that would consume 41% of the total funding allocated to enable the build. This makes the project unachievable for the marae. Despite all the support and preparation to bring the project to this stage of development, this final hurdle was perceived as unsurmountable. Therefore, the Board made the call to discontinue the project. The marae has since brought onsite three portable cabins to fulfil the purpose of the tiny house project and, in working with the funders, had the initial funding approved and repurposed for a playground for children whose mothers come to the marae for respite.

Papatūānuku Kōkiri Marae specialises in kai (food) security and provision of restoring the practice of kai sovereignty for urban-based Māori and communities across Tāmaki Makaurau. Creating a temporary accommodation option for respite with the whare kāhui provides the chance to share this prototype for other marae to consider. In this instance with Papatūānuku Kōkiri Marae, it is evident that the compromise that the marae resulted in signals the barriers presented with local government administration thwarting marae efforts to effectively participate in housing provision.

2.3. Mātaatua Marae–Baari Mio (MRC)

Mātaatua hangaia he tāwharau: to provide shelter and solace, a safe place for our people.

Mātaatua Marae was established in 1978 with agreement from Te Ārikinui, Te Ātairangikāhu, and te kuini Māori to build our marae on Tainui whenua for the purposes of housing and supporting Ngāti Awa whānau here in Tāmaki who had migrated along with the many rural whānau during the mid-1950s to the late 1970s.

Its primary purpose was to provide a place for Ngāti Awa whānau to gather for all purposes and remain connected as a whānau and an iwi, being so far away from home. Forty-one years on, the marae remains a pillar of strength and unity here in our community and for our Ngāti Awa whānui(wide) here in Tāmaki.

The dream for Mātaatua Marae is to provide “a solutions-based, Māori-led, community whānau service and housing provider that supports total wellbeing for whānau, hapū, iwi and hāpori (community) with focused initiatives that encourage a sustainable, clean, green approach to urban housing and social, financial and whānau wellbeing, with the intent to support Māori to thrive” (B. Mio, personal communication, 6 December 2021).

As so many whānau from Ngāti Awa domicile here in Tāmaki, it is important to maintain connections to all whānau to ensure the marae is viewed as a safe place and offers support to those who need it—whether that be through cultural connectedness and wānanga (learning), health and social services, or education and housing. That vision is to be the hub of wellbeing for the wider whānau. One of the many aspirations for whānau wellbeing and whānau thriving is to develop housing that is centralised around the marae and enables the marae to provide as many of the essential services previously mentioned. Allowing whānau affiliated to Mātaatua the ability to enhance whānau oranga (whanau wellbeing) through whakapapa (genealogical links) to marae and the hononga (connection) of marae to the whenua (land), whenua to taiao (environment), taiao to wai(waters), wai to moana (sea), moana to whakapapa (genealogical links), and whakapapa to this marae is our ultimate goal. All aspects of wellbeing are led and driven by our whānau for our whānau, from one of our most respected, traditional places of assistance for Māori—our marae.

The overall concept for reimagining kāinga in the urban setting for Mātaatua Marae is to revert to a more regenerative and eco-sustainable approach to living. The basic principles and ways of living, such as the benefits of communal kai maara (gardens), are more than just possibilities but are dreams that the whānau have been instrumental in realising. An example and a result of this was the master-planning wānanga in 2021, as seen in the above plan

Figure 3. It depicts the housing, education and social service hubs surrounding the marae, with adequate green space for gardens and activities in close proximity to natural wai (waterways) and moana (sea)—a dream for us that will soon become a reality.

Mātaatua Marae has owned kaumātua accommodation located near the marae and obtained through Māori Affairs since 1980. With this foresight to ensure their Ngāti Awa elders in the city would be the responsibility of the marae community to care for and keep close to the marae proper, the prospect of expanding their housing portfolio to secure space for other whānau in need is an imminent development. This marae is actively seeking to be approved as a Community Housing Provider and take on the commitment of social-housing provision within their own specifications of Mana Motuhake (power and authority). A challenge that has been presented for Mātaatua to achieve their vision is the current negotiations with crown entities regarding the land status of the marae site and the long-term prospect of Mātaatua remaining there and being able to grow their locality.

2.4. Manurewa Marae–Kahleyn Evans (MRC)

Amōhia ake te ora o te iwi- ka puta ki te whei ao.

The health and wellbeing of our people are paramount.

This is a tongikura or prophetic saying from the Māori King Tūheitia Pōtatau Te Wherowhero Te Tuawhitu that Manurewa Marae identifies with, as it reflects the work and care the marae puts into the people of their community.

The impetus for a marae started back in the 1970s when a group of whānau within Manurewa came together with the aspiration to have a marae where we could bring our people together. A lot of Māori in Manurewa were from different places and were not able to return home for things like tangihanga (funerals, grieving rituals). This roopu (group) and their dream were to bring people together so they could hold tangihanga and bring other cultures together within the community.

Over time, the marae has definitely grown. There is a wharekura (Maori language secondary school) onsite, clinic services and rongoā (Māori medicine) services established there now. Whānau Ora (Maori approach to integrated social services) and a foodbank have been developed, so the marae has really grown from the original whakaaro (thought, thinking) into something that really gives back to the community and provides for the wider community.

Last year the Board assembled to reimagine kāinga and established a marae master plan to bring in kaumātua and kuia (elder) housing, as that was one of the main aspirations and dreams that the founding whānau that started the marae really wanted to happen. This vision has been reinstated and put into the marae’s future-thinking design plans.

The red building in the above diagram sits on the current border of the marae land. The land from this point down on the map in

Figure 4, is the reserve next to the marae. The marae Board is looking at extending our marae onto that reserve space so that our kāinga can be developed there for our kaumātua and kuia, where they can live on the marae, be a part of the marae, and share their knowledge and mātauranga (Māori knowledge) with the marae and the community.

There is a definite drive to connect more with the taiao (environment), so a wharf is in the plans that extend out into Te Mānukanuka o Hoturoa (original name for Manukau Harbour). Our aspirations are to implement waka ama (paddling canoes) and other similar activities that create an enduring relationship with our whānau, our community, and the taiao (environment).

Soil testing is being arranged as a part of our taiao project, which the Board is enthusiastic about pursuing. This will regenerate connectivity between the marae and the environment. The other reason soil testing is important is to align the amazing master plan with what sites on the marae are best suited for the placement of kai maara/gardens and growing rongoā (medicinal) native trees and which places are better suited for erecting houses or buildings.

The marae is also in the throes of repurposing our puna reo (language spring), which was built around ten years ago for early childhood education. Since then, times have changed, as has the potential best use of this building, and the need for an early childhood facility is no longer as relevant as it used to be. There are so many ECEs out in the community now, and the presence of COVID-19 has really changed the demand for learning spaces, reviewing the whole purpose of what the puna reo might be used for. The marae is considering using it for things like workshops and wānanga (learning). It will still be within education, for conferences, hui, and these kinds of events, but not early childhood education as originally intended. At the beginning of the year, Manurewa Marae hosted the MOKO research hui in this facility. These are the types of activities the Board is now looking to use the puna reo space for.

In the future, the marae is really focused on the taiao (environmental) aspect and bringing together our kaumātua and kuia (elders) to recreate that relationship where whānau can come in to learn about the taiao and learn from our kaumātua a bit about who we are as Manurewa Marae. The intent of the Manurewa Marae, from conception to now, is to promote the coming together more as a community.

Manurewa Marae shares the land restrictions that have been highlighted previously for both Mātaatua and Papatūānuku Kōkiri Marae. As their service provision has dispersed across the Manurewa community, the appeal for more facilities onsite to house operations and mushrooming numbers of staff and volunteers is apparent. Obtaining space adjacent to the marae on reserve land and repurposing existing buildings is serving to contain current demands, as well as taking into account the expansion of services to include social housing. The marae is presently an emergency transitional housing provider, with homes they manage offsite. The reimagining of kāinga for this marae is a new consideration and a long-term plan, not something of a priority in the immediate future.

2.5. Papakura Marae–Luella Linaker (MRC)

Kōtahi te kōhao ō te ngīra e kuhuna ai te miro mā, te miro pango, te miro whero. There is but one eye of a needle through which the white, black and red threads must pass.

This is an apt metaphor for Papakura Marae. The wharenui is named Te Ngīra, the needle, an enduring reminder of our purpose and responsibility.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Māori moved to Papakura from the East Coast, the Far North and from across the country. The distance home was long, and it was too costly to travel back regularly. A number of families were instrumental in establishing a Māori complex that met the social and cultural needs of Māori and integrated Pākehā into understanding Māori society in Papakura.

Intense fundraising began and continued over many years, and in 1979, work began on the whare kai. The foundations of the present marae began with support from Māori in the community, both mana whenua (original inhabitants) and mātaawaka (migrant urban kinship groups).

Kaumātua (elders) are an invaluable part of Papakura Marae. They come from across Papakura and Manurewa, with sometimes little notice, to support marae kaupapa. The marae values their wisdom and knowledge, their mana (authority, prestige), and the important role they play in Māori society. That was the genesis of kaumātua housing in 2017, the true essence of manaakitanga (caring), mana akiaki (enhance or influence authority), to provide kaumātua with a home here on the marae where they support the marae and where the marae supports them.

Kaumātua were involved in developing the feasibility study and gave their thoughts about the vision and how it should work in practice. This led to the concept design. According to the 2018 Census, only 31% of Māori own their own homes (

Stats NZ 2020). Unsurprisingly then, almost all of the kaumātua who were interested in staying at the marae were renting and, therefore, at the mercy of the housing market in their twilight years.

Papakura Marae is on a Council reserve, which means it is owned by the Papakura Local Board. Local Board permission was required to be able to build on the reserve, even though it was already a marae complex. The marae has worked hard to strengthen its relationship with the Local Board, and at the meeting, when the Chair moved the recommendation to allow the kaumātua housing development, every member of that local Board put their hand up to second the motion. They all wanted to support the marae development. There were a number of key contributors over time, people instrumental in Auckland Council that helped this building project get across the line.

Similarly, strengthening relationships with Ngāti Tamaoho and Ngāti Pāoa has been both critical and important. As manuhiri in Papakura, it has been important from day one that the marae maintains close relationships with and support from mana whenua.

The Māori Housing Fund was launched at Papakura Marae by the Hon. Jacinda Ardern and the Hon. Nanaia Mahuta and funded the building of the first six whare. Landowner approval and the concept design were key components of a successful application. Three further whare were approved in 2021 and are currently under construction.

Supporting the local economy is important, and Papakura Marae used local architects, builders and project managers. It is different when they are local: they put their heart into it, the locals know them; they have skin in the game; it is their legacy too. While none of these specialists were Māori, they really understood the marae vision and the importance of the marae to the whole community. They knew about Papakura Marae but never had a reason to engage. Now they see how important the marae is to the whole community, and how open and accessible the marae is for everyone, the role the marae has played through COVID-19 to support everyone.

The marae established a sub-committee that, with the marae Chief Executive and the Chief Financial Officer, met weekly with the building team. This was a good way to understand what was going on, to brainstorm solutions to any problems and look at opportunities as they arose.

The marae developed good relationships with the Council and central government staff, which moved the project across the line in a number of instances. It was really important to have a single point of contact within each agency and Council—someone who could open doors and give it to us straight. Auckland Council’s Māori Housing specialist navigated the complexities and internal roadblocks of their own organisation on the marae’s behalf.

Development in the first six whare began in 2020, later than hoped but impacted by COVID-19.

There were many hiccups along the way, but the strength, dedication and belief of the team is what allowed it to progress. The first six whare were blessed and opened in November 2021. This was scheduled for late August when our first kaumātua would move in, but COVID-19 disrupted that.

Below in

Figure 5 is Noelene. She was the chief fundraiser in the 1970s and 1980s. She organised food stalls at Sweetwaters festival, housie events, and hīkoi to Maraetai. Though Noelene sadly passed away in 2021, it is for people like her that this housing is intended; those who have given to the marae with love and care for the people.

Each whare has its own kaitiaki (guardian), carved by esteemed kaiwhakairo (carver) Ted Ngātaki. Each whare has two bedrooms, designed for kaumātua, that are easy to move around in, including walk-in showers. They even have their own private balcony overlooking the reserve, so kaumātua have a private outdoor area when the marae has lots of manuhiri (guests). This is what the whare are about; our kaumātua living onsite, supporting our marae, and sharing and passing on knowledge to tamariki, rangatahi and pakeke. More importantly, Papakura Marae is able to support them with wraparound services such as an onsite clinic and pharmacy and a whole range of services that the marae provides for the whole community.

For marae looking to build housing, do not let go of the hoeroa (long row, long game); it is your build, so make sure that it works for you and your whānau and hapū. You are the marae and Tikanga experts. Do not let the building experts lead. You need to do this together. Find the right people who buy into your vision and who have the skills and expertise to advance your marae to an enduring successful outcome.

Papakura Marae has been strategic in securing funding and advocating the urgency of bringing kaumātua into the marae fold to nurture and grow the vital leadership within every Māori community. This was timely, with the country learning to function in a pandemic and amplifying efforts to keep our elderly populations physically distanced and socially connected. Papakura Marae, like the others in the MOKO research project, has embodied the quintessential role that urban marae in South Auckland has played in looking after whole communities. An emphasis on relationships, connections and maintenance of these relationships with potential stakeholders is indisputable in the above accounts, in which to progress an immediate and achievable housing response as within their reach.