1. Introduction

The enduring pro-secession campaign in Catalonia (2010–2017) created a deep political and affective fracture into two sizeable and opposing citizenry segments, those who prefer remaining in Spain (unionists) and those who want to secede from it (secessionists). The stagnation of the division on the issue of Catalonia’s secession from Spain was a persistent attribute of the political landscape, in the region, for years. Since a direct question about secession was introduced within regular CEO Barometer surveys

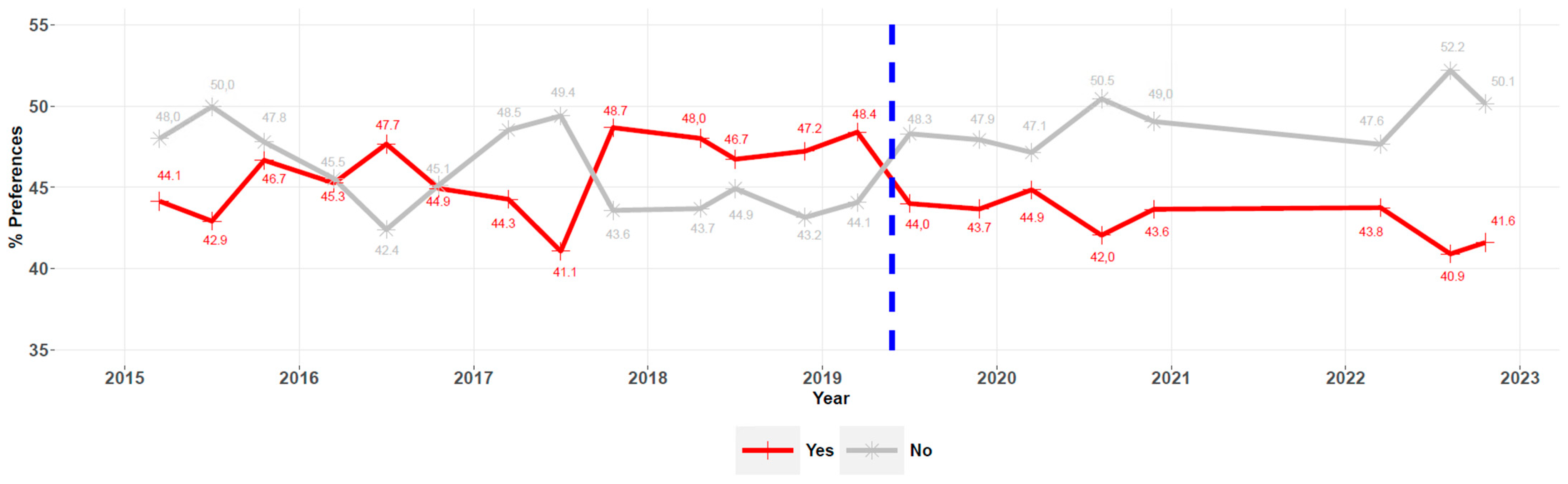

1, the proportion of citizens who want secession from Spain and of those who refuse it has remained almost unchanged since 2014. Rounding up percentages, there were 42–45% of the population that expressed their aspiration to break with Spain; there were another 44–48% who wanted to remain in Spain; and the remnants (6–10%) were either agnostic or not interested in the issue. This was still the case on the 2022 CEO polls, five years after the failed independence proclamation by the Catalonian Autonomous Parliament (October 2017)

2. The predominance of the citizenry segment who would prefer not to break with Spain appear to have consolidated its scant advantage recently according to the CEO Barometers of March, July and December 2022 (see Figure 1).

The results of the last three regional elections (2015, 2017, 2021) reaffirmed the neat political division. By adding and rounding up the figures on each of these elections, the difference between the total number of votes for secessionist parties and the total number for unionist parties was around 150,000 votes. This was the small distance

3 that separated them, in three very different circumstances: from the 2015 elections, called by the Regional Government as a plebiscite on independence; that of December 2017, called by Spain’s central government to end the suspension of Catalan autonomy that had been decreed after the (failed) independence proclamation; and that of February 2021, held within a distressing pandemic context. The usual but narrow unionist advantage in votes (but not in seats), was lost in the last election, as the drop in the large turnout led the unionists to lose nearly one million votes, while secessionists lost around 600,000 votes. Greater unionist reluctance to go to the polls facilitated the shift in favor of secessionist forces, with the same margin of difference (150,000 votes), which consolidated their majority at the Regional Parliament. Consequently, not only did the opinion polls reflect an enduring division between two halves of the Catalonian citizenry, but repeated electoral behavior reproduced such a partition.

In several longitudinal studies (

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b,

2020), we shed light on the main factors that favored the appearance of a deep political fissure between secessionist and unionist segments of the Catalonian citizenry, amid an increasing social and affective distancing around the secession issue. By building upon the complete series of data from official CEO Barometer polls, the evolving changes in

national identity (“

sense of belonging”), throughout 2006–2019, were displayed in relation to other variables. These analyses included 92,038 respondents from 47 surveys. Variations in

national identity across the two main citizenry segments, those with a family language of Catalan

versus those with a family language of Spanish were studied first. Previous findings, either from surveys or electoral results, had long-established the priority of this ethnolinguistic cleavage rooted on family ascendancy origins (Catalonian ascendancy vs. other Spanish regions) (

Barceló 2014;

Álvarez-Gálvez et al. 2018;

Guntermann et al. 2020;

Maza et al. 2019;

Maza and Hierro 2022;

Miley 2007,

2013;

Miley and Garvía 2019;

Romero-Vidal 2019). Our longitudinal results confirmed such preeminence. There were also noticeable changes in national identity associated with media preferences—that is, between TV and radio outlets controlled by the Regional Government (broadcasting exclusively in Catalan language), and other TV and radio outlets—thus confirming a relationship that had also been suggested previously (

García 2013;

Tobeña 2017a;

Valera-Ordaz 2018). Since family language/ascendancy and media consumption trends are interwoven within the region (

Miley and Garvía 2019;

Tobeña 2017a;

Valera-Ordaz 2018), our findings highlighted the role played by such interactions on the deepening of the political and affective fissure between secessionists and unionists (

Balcells et al. 2021;

Merino 2022).

We have extended these longitudinal analyses trying to capture changes that may have happened since the failed independence proclamation in October 2017, because a series of events of major relevance, both domestic and global, have occurred since then. The trial and sentencing for sedition and embezzlement, in autumn 2019, of prominent Catalonian politicians who led the secession bid was the first one. They were condemned to spend several years in prison, a sentence that triggered an outburst of civil unrest, with vandalistic disturbances and fights with riot police battalions lasting for weeks in downtown Barcelona and on highways, railways and streets in other towns across the region (

Tobeña 2021). Two years later, in early summer 2021, the imprisoned secessionist leaders were released from jail as a result of the pardon issued by the Spanish Government

4. A second major event was the eruption of harsh, long and successive waves of the coronavirus pandemic that started, within the region, in early spring 2020. The threat and consequences of the infectious disease halted the vigorous pro-secession activism to a great extent for more than two years. As a matter of fact, CEO Barometer polls were suspended for more than a year in 2021, and they were only resumed in March 2022. Lastly, a third outstanding event was the eruption of a major European war between Russia and Ukraine, in February 2022, that added to the exceptionality of the period.

In the present study, we extended our previous longitudinal analyses of CEO Barometer surveys to focus on the role of the ethnolinguistic cleavage and partisan media influence upon the ongoing division among the Catalonian citizenry. Our previous findings showed that second only to family language cleavage effects, media consumption habits (following regional media controlled by pro-secession Regional Government vs. general outlets) were a main vector for significant entrenched alignments of the citizenry on the issue of secession, through the period 2006–2019 (

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b,

2020). Family language and ancestry origins are hardly modifiable variables, but preferences for media outlets and platforms may change a lot due to a number of influences. There is a general agreement, in political science, that the media play a crucial role in shaping national identities, although the exact nature of such a relationship generates unending discussions (

Prior 2013;

Mylonas and Tudor 2021). The strength and direction of the relationship between media influence and partisan alignments based on ideological or other kind of cleavages is still a highly debated issue, in part because it is unusual to detect large and sustained effects that might be unambiguously attributed to one or the other factor (

Slater 2007;

Iyengar and Hahn 2009;

King et al. 2017;

Prior 2013;

Quattrociocchi et al. 2011;

Qvortrup 2014;

Shoemaker and Stremlau 2014;

Valera-Ordaz 2018,

2023). As it is even more unusual to detect consistent covariations between media following preferences and national identity oscillations along unstable and variable political contexts, it was important to ascertain the continuity of the trends we had previously found.

The unexpected and new scenario that emerged during 2019–2022 had several major milestones: (1) The strict confinement and health measures to control the outbreaks of the COVID-19 disease, followed afterwards by two long years of active measures against illness dissemination that limited and prevented civilian concentrations. (2) The establishment of a continuous parliamentary alliance in Spain between the Socialist party (PSOE), ruling the Central Government since the end of 2019, and the main pro-secession force (ERC), leading the Regional Government in Barcelona. Such an alliance opened a period of uneasy but sustained collaboration that avoided continuous litigation and political confrontations. (3) The alarming shock and economic challenges that European countries had to confront from February 2022 as a result of the Russia–Ukraine war.

All of that resulted in a situation, within the region, characterized by a progressive decline of political and social tensions among the citizenry: there was a substantial decrease in demonstrations, protests and confrontations related to secession issues, accompanied by a notorious reduction in disagreements between the Central Government, in Madrid, and the Autonomous Government, in Barcelona, related to the secession conflict (

Tobeña 2022). No major protests, street fights or serious disturbances related to the secession issue have occurred in the region since the end of 2019. Participant numbers on pro-secession massive demonstrations celebrated on major festivities have decreased enormously

5, and the overwhelming social pressure enacted by the exhibition of secessionist flags, symbols and adverts that monopolized streets, balconies and roundabouts almost everywhere, as well as clothing adornments that were used to proclaim pro-secession attitudes by many people, have greatly diminished or fully disappeared (

Tobeña 2022). This new period of apparent calm over the secession bid (2019–2022) demanded a further longitudinal analysis to ascertain if the variables that we had characterized as the main fracture lines for the sociopolitical division going on among Catalonian citizenry presented compelling variations that reflected the new scenario.

2. Methods

To study the longitudinal evolution of pro-secession vs. anti-secession preferences among Catalonian citizenry, we worked exclusively with data obtained by CEO Barometers during the period 2006–2022. These data were supplied in open access from January 2006 to the present and include the totality of biannual/triannual systematic surveys that CEO launches with regularity. Sample sizes of these surveys oscillated between 2500 and 1500 citizens each. In our previous studies (

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b,

2020), we analyzed responses from up to 92,038 participants on 47 surveys covering the period 2006–2019. Here we added data coming from six subsequent CEO Barometers, between December 2019 and December 2022, representing N = 11,500 additional observations. We had, thus, 100,038 responders for the present analyses.

Our focus, the longitudinal analyses of opinion trends about the issue of secession, is a multifaceted phenomenon that can be quantified by many variables, among others by “

National Identity” (“sense of belonging feelings”), “

Affirmative/Negative answers on a referendum about secession” and others. We selected, from the start, “

National Identity” (“

Sense of belonging feelings” in CEO surveys) as our main target because it was present in the whole series of CEO surveys, it encodes the core ingredient of individual’s sociopolitical identity, and it does not depend on changing labels that may distort results. Across the whole period 2006–2022 and for all Catalonian population,

National Identity segments were defined as follows: (Cat) “

Only Catalan”; (Cat > Spn) “

More Catalan than Spanish”; (Cat = Spn) “

As Catalan as Spanish”; (Spn > Ca) “

More Spanish than Catalan”; and (Spn) “

Only Spanish”. We explored the relationship between our main variable with others related with the ethnolinguistic cleavage that characterizes Catalonian citizenry. Specifically, we considered, for each survey, the qualitative variable “

Family language” (Catalan, Spanish, Both, Others), and the binary variable “

Follow news on public regional media or not” (regional media = TV channels or radio stations under control of Regional Government and broadcasting in Catalan language only). The longitudinal changes in

national identity between 2006 and 2022 were plotted for all population distinguishing by the main family language groups: Catalan language (34.2%, the size of this citizenry segment in the last linguistic survey, July 2019) and Spanish language (58.1% the size in that survey). We plotted only the more frequent identities in each linguistic group: people who had both languages, Spanish and Catalan, as their family language (3.7% their size in that July 2019 survey) exhibited an intermediate behaviour. We also added a smooth 95% confidence band based on a generalized additive model implemented through the R package mgcv (

Wood et al. 2016;

Hastie and Tibshirani 1990).

Historical events that might have been relevant for the evolution of the variables along the studied period were marked on the plots by vertical lines. These events were: the date when a new Home Rule was approved (2006 New Statute of Autonomous Government); the resolution of the High Spanish Court (Tribunal Constitutional-TC) that sanctioned 14 articles (over 223) as contrary to the Spanish Constitution (June 2010); the peak protests of the social 15M movement (15M Peak Protests, June 2011); the regional elections of 25 November 2012 (25N); an illegal consultation about independence, 9 November 2014 (9N); the regional elections of 27 September 2015 (27S); the illegal referendum about secession, 1 October 2017 (1Oct); the regional elections of 21 December 2017 (21D); the eruption of COVID-19 first wave epidemic in Catalonia, March 2020 (COVID); the regional election of 14 February 2021 (14F); and the start of Russia invasion of Ukraine, 24 February 2022 (UKRWar).

Finally, we applied the same analyses to other variables (

SI: Supplementary Information). First, to the positive/negative explicit answers in the event of a legal referendum about secession from Spain. This was a qualitative variable with three possible outcomes: Yes, No and DK/NA, reproducing the approach and contrasts of the main methods exposed. Second, to participation at regional elections (measured in CEO surveys by individual memories of having participated or not in the last regional election).

For particular comparisons, several non-parametrical and parametrical statistical contrasts (Sign Tests, regression analyses), specified in the Results section, were applied as required to the series of data coming from regular surveys on representative and different population samples, specifically to highlight the change in trend that occurred in mid-2019, between affirmative and negative responses in a hypothetical secession referendum, both in the population as a whole and when segmented by family mother language.

To identify important changes potentially linked to specific events (“

turning points”) detected in the series, we used the R package ecp designed for nonparametric multiple change point analysis of multivariate data (

Matteson and James 2014), which implements a divisive hierarchical algorithm to detect reasonable change points through a bisection method and a permutation test. Since our database can be viewed as multivariate time-ordered data, it opens the opportunity for change point analysis under minimal assumptions. The aim was to identify just statistically (data-driven) significant changes potentially linked to specific events (“turning points”), on the multivariate series data. We do not use hypothesis here, we just tuned the algorithm using 0.025 significance level and demanding at least six observations, from 1.75 to 2 years, between change points. The change points obtained using this approach are indicated as vertical red lines in the Figures. These change points were obtained using the complete profile of

national identity of the different groups: from those who self-identified as

Only Spanish to those who self-identified as

Only Catalans, including also the class of DK/NA (do not know or no answer). Hence, they are multivariate results, although the series displayed in the figures show only the evolution profiles of some national identity feelings for each linguistic group.

We are fully aware of the limits and restrictions adopted in the present analyses of an obviously multi-causal phenomenon. Due to the characteristics of the data (opinion surveys from different representative samples gathered across seventeen years), we limited ourselves to studying significant stochastic dependencies between variables: just a strictly statistical depiction (descriptive plus correlational), although it is true that, in this context, high stochastic associations might suggest plausible explanations of the mechanisms involved in observed trends. We do not pre-assume a theory, so our emphasis is directed to only exploit a rich database to unveil significant associations.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the percentages of citizens responding YES/NO to a direct question about secession from Spain, in a hypothetical referendum of self-determination in CEO Barometer surveys. The answer “No” was given consistently more frequently than the answer “Yes” (a difference of 2.1 to 11.3 percent points), consecutively from the middle of 2019 (blue line) when the trial of the secessionist leaders at the Spanish High Court was set for sentence

6. This systematic streak would be very unlikely under the hypothesis of the equality of both options, and even detectable through a simple Sign Test (used just as an approximation), with a significance level less than 1% (

p-value 0.00781).

Figure 2 shows the percentages of citizens responding YES/NO to a direct question about secession from Spain in a hypothetical referendum of self-determination, segmented by family language, across the period 2015–2023. There are important differences, always over 45 percent points (sometimes over 50% points), when segmenting the population for family language. It is also noticeable that there is a significant descending trend, starting in mid-2018, in both segments. This trend can be evidenced with a simple regression analysis (with a stabilizing transformation of the variance) with significance levels lower than 1% (

p-values 0.00266 and 0.00596, respectively) that are more pronounced in the family language Catalan segment (12.5%), although this last statement did not reach statistical significance.

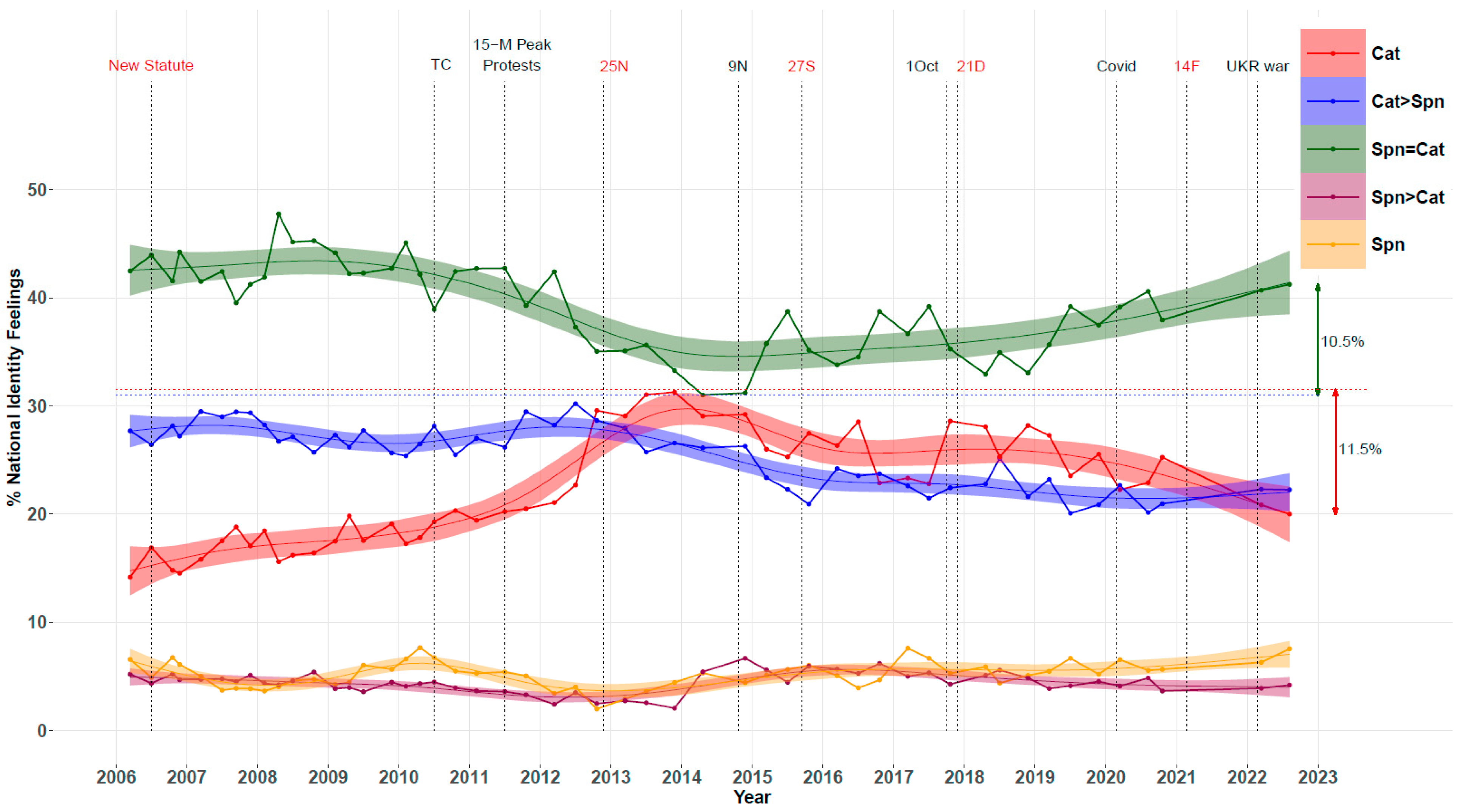

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the different

National Identity segments (Cat: “

Only Catalan”; Cat > Spn: “

More Catalan than Spanish”; Cat = Spn: “

As Catalan as Spanish”; Spn > Ca: “

More Spanish than Catalan”; Spn: “

Only Spanish”), across the whole period 2006–2022, for the whole Catalonian population. In 2018, the reversion started of the fairly strong variations that had peaked during the mounting years of the secession campaign (2013–2017). There were noticeable increases in the percentage (10.5%) of the feeling “

As Spanish as Catalan” and a substantial reduction in the percentage (11.5%) of the feeling “

Only Catalan”, both measured from 2015.

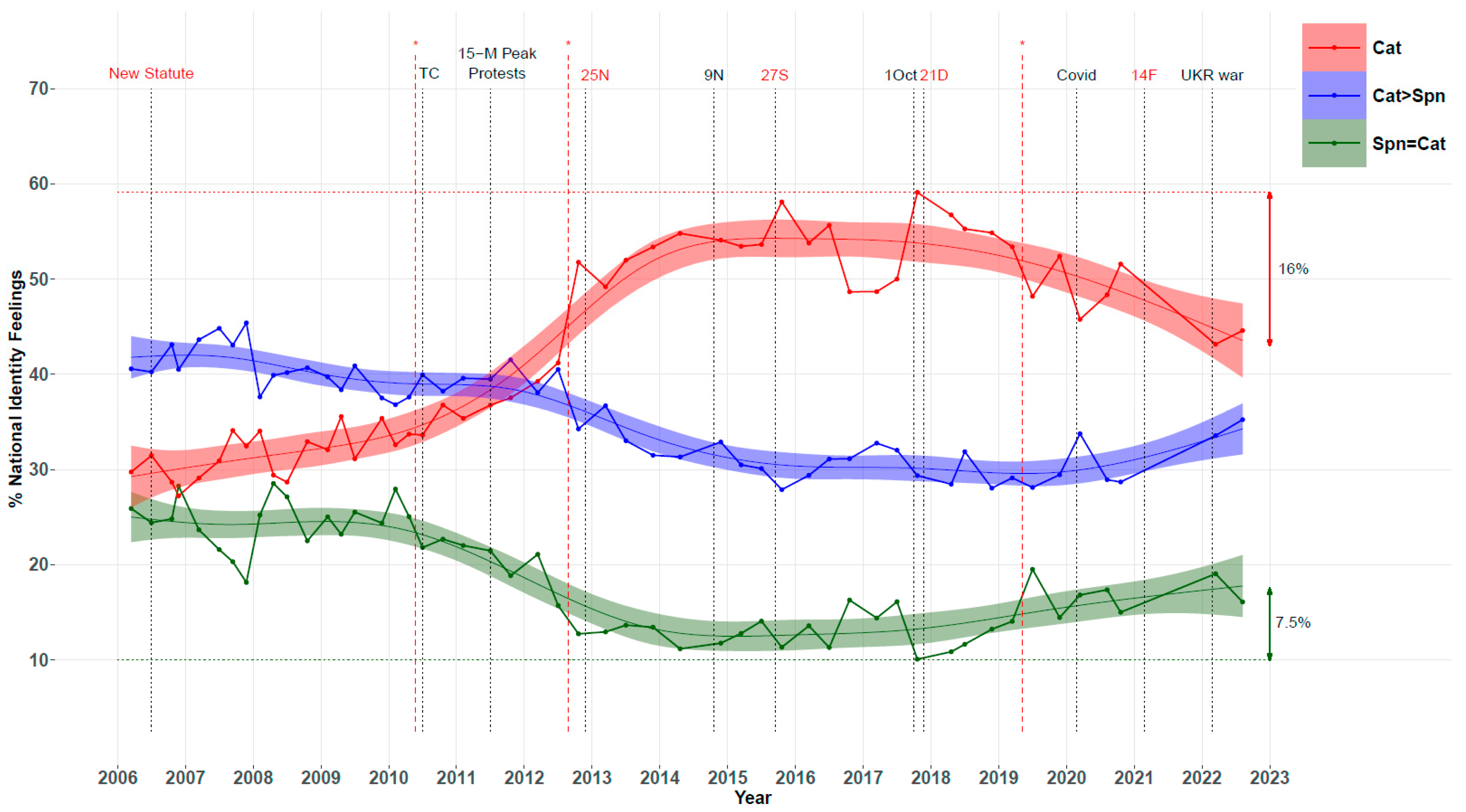

Figure 4 shows the evolution of National Identities (Cat: “

Only Catalan”; Cat > Spn: “

More Catalan than Spanish”; Cat = Spn: “

As Catalan as Spanish”) across the whole period 2006–2022, for the citizenry segment with family language Catalan (37% of the citizenry). There were relevant changes since 2018; in particular, there was an increase in the percentage (7.5%) of the feeling “

As Spanish as Catalan” and a substantial reduction in the percentage (16%) of the feeling “

Only Catalan”, that came from an abrupt but durable high level in this population segment. Moreover, a multivariate change point was detected (ecp R package, at significance level 0.025), approximately in the middle of 2019, when the trial of the secessionist leaders at Spain’s High Court was set for sentence.

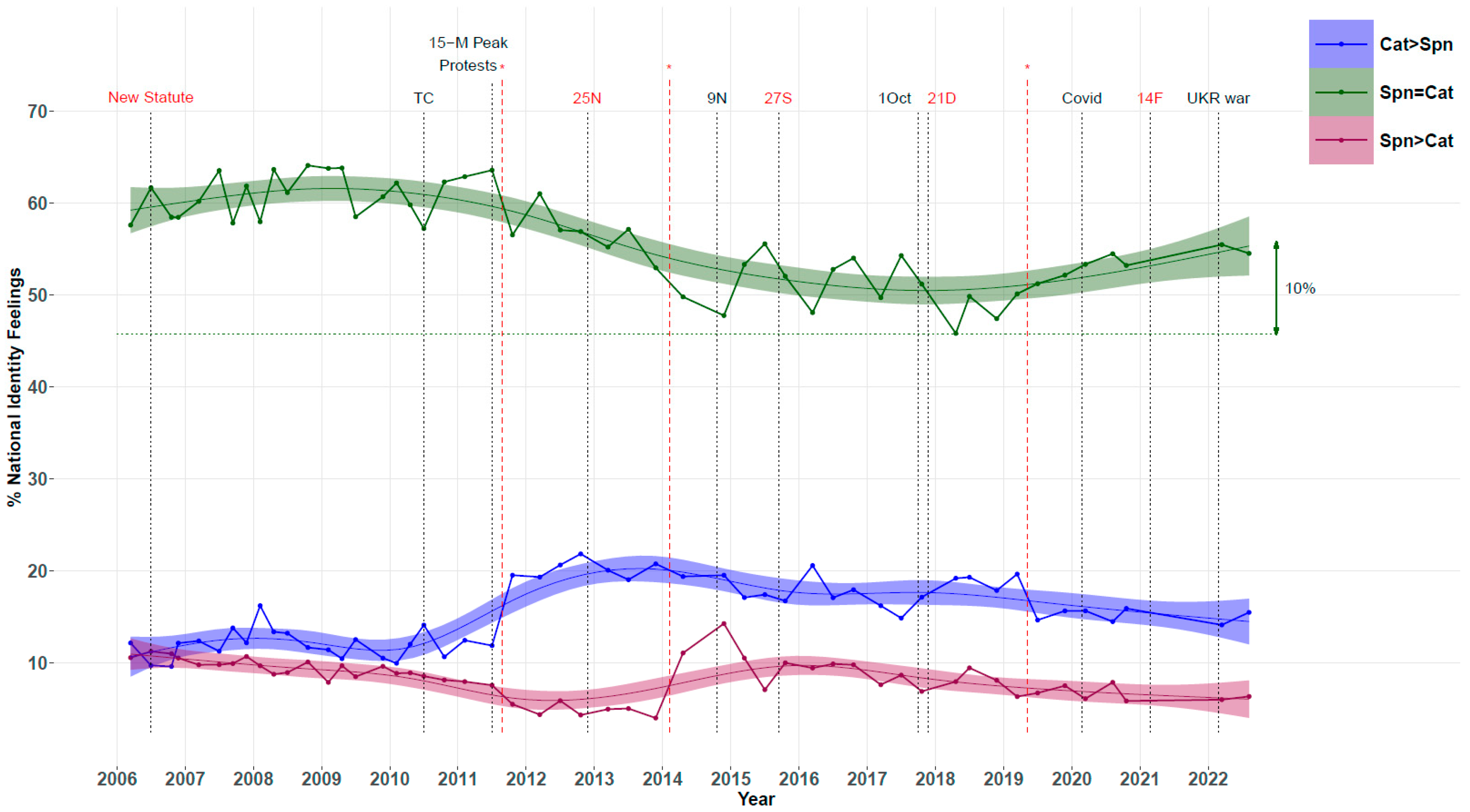

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the National Identities (Cat > Spn: “

More Catalan than Spanish”; Cat = Spn: “

As Catalan as Spanish”; Spn > Ca: “

More Spanish than Catalan”) across the whole period 2006–2022 for the citizenry with family language Spanish (54%). There were changes since 2018; in particular, there was an increase in the percentage (10%) of the feeling “

As Spanish as Catalan”. Moreover, a multivariate change point was detected (ecp R package, at significance level 0.025), approximately in the middle of 2019, when the trial of the secessionist leaders was set for sentence.

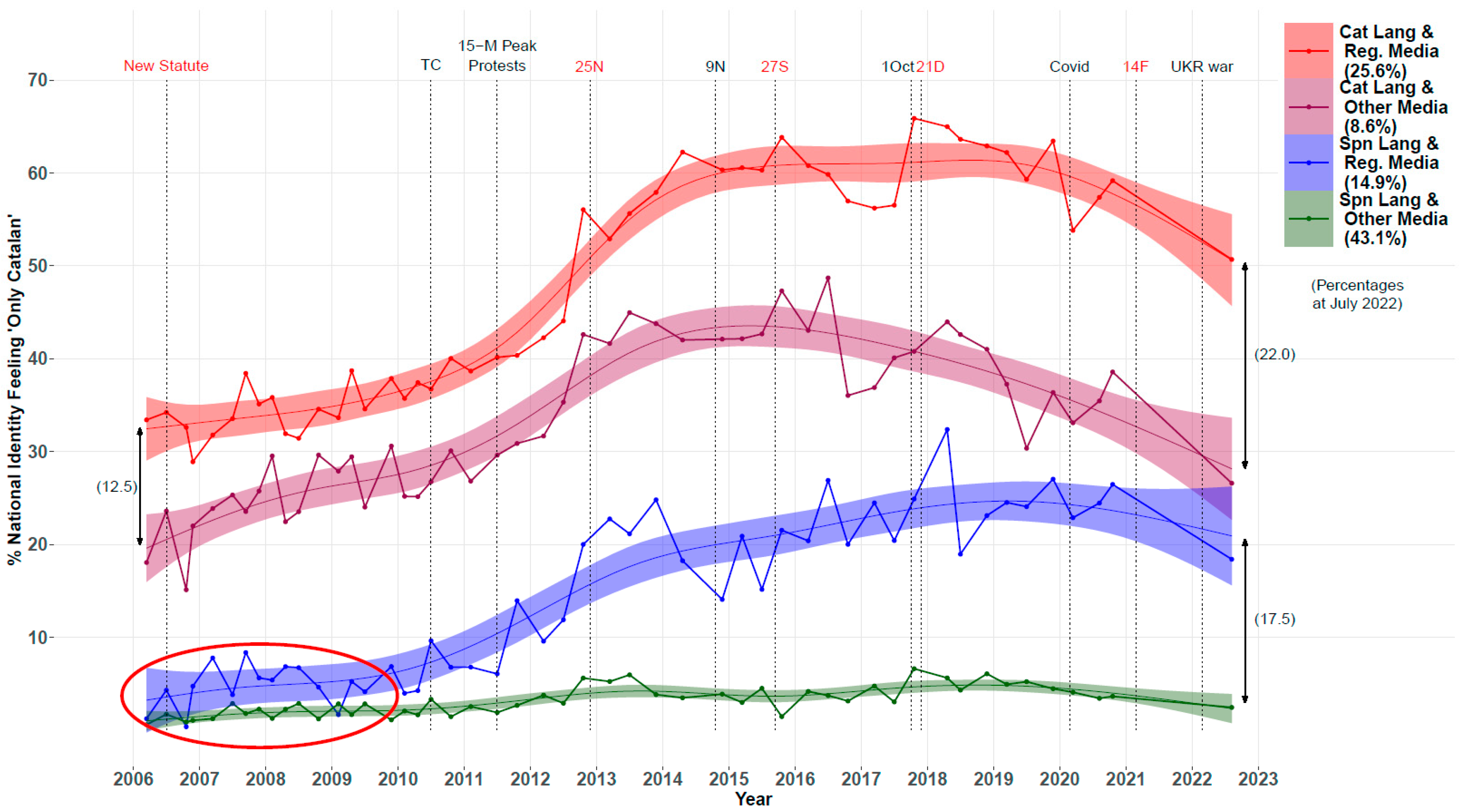

Figure 6 shows the evolution of variations in the proportion of feelings of national identity “

Only Catalan”, segmented by family language and regional media consumption. There were systematic differences in the group with family language Catalan according to whether or not they followed political news in the regional media (in July 2022, 22% points of the estimated trend). The same happened within the segment with a family language of Spanish (in July 2022, 17.5% points). Following regional media outlets was accompanied by increases in “

Only Catalan” identity in a systematic way. All these differences were statistically significant since they appeared consistently through the whole period, with the exception of the first surveys in the segment with family language Spanish. Note also that, in that case, both groups differed little between 2006 and 2010 depending on whether or not they followed the regional media (red ellipse).

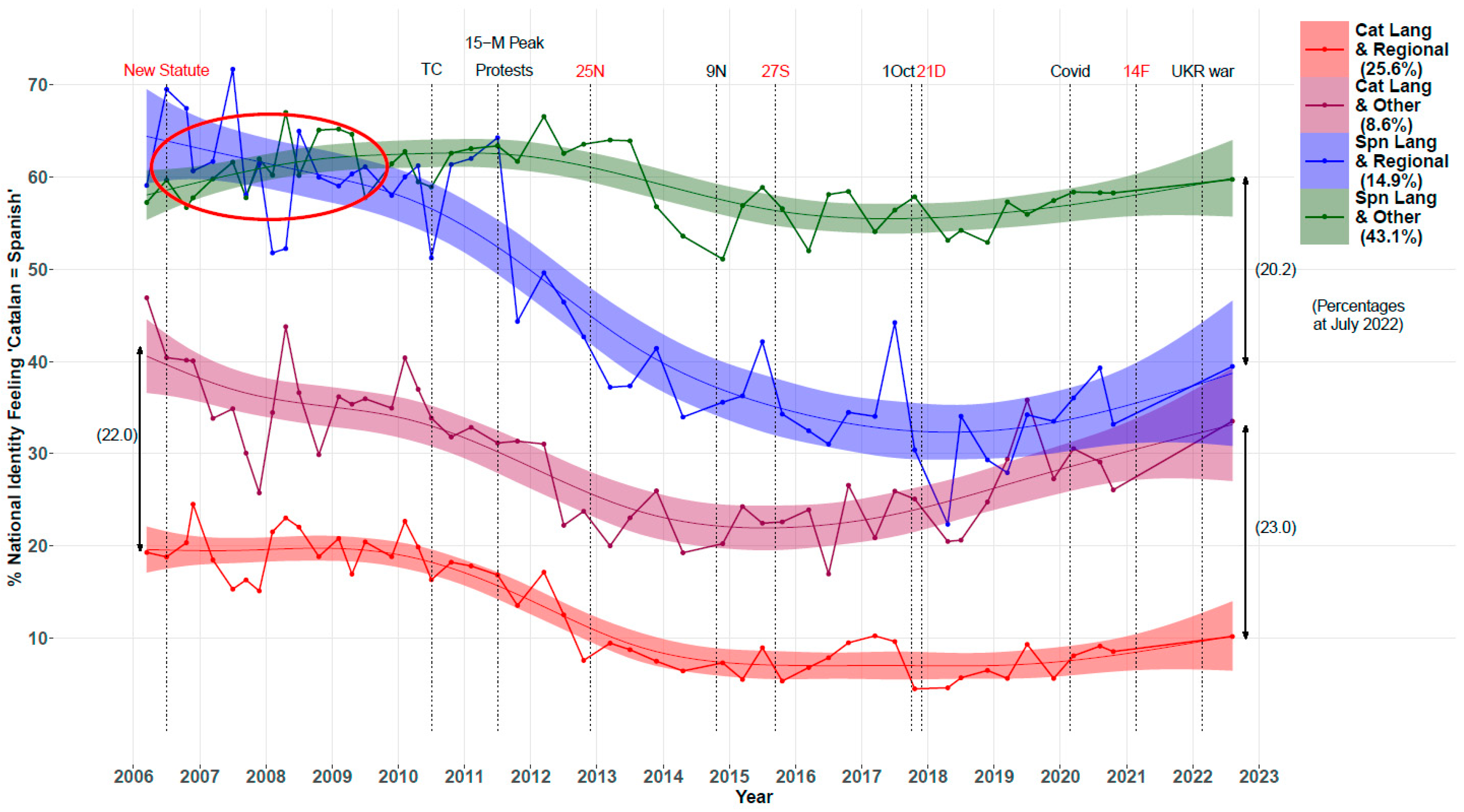

Figure 7 shows the evolution in the proportion of “

As Spanish as Catalan” national identity segmented by family language and regional media consumption. There were consistent differences within the group with family language Catalan across the whole period, according to whether or not they followed political news in the regional media (in July 2022, the difference approached 20% of the estimated trend). The same result happened within the segment with family language Spanish (difference in July 2022: 23% points), except for the first year. The prevalent tendency was of diminishing the dual national identity (Spn = Cat) when the media preference was for regional outlets. These trends were statistically significant since they consistently appeared through all of the period, with the exception of several points at the start of the series on the segment with family language Spanish when both subgroups differed little depending on whether or not they followed the regional media (red ellipse). The noticeable effects of regional media outlets only appeared after 2010 in that segment.

Figure S1 shows the percentages of citizens responding YES/NO to a direct question about secession from Spain, in a hypothetical referendum of self-determination, segmented by family language and regional media consumption. There were important differences in both family language segments according to whether or not they followed the regional media. These differences were between 38% and 40% points in July 2022. Once the family language was fixed, the contrasts between segments were statistically significant under any simple Sign Test (used as an approximation), with a significance level less than 1%. Notice also that, from mid-2019, the group with family language Spanish that followed news through the regional media exhibited a proportion of “Yes” consistently higher than those with family language Catalan that did not follow news through the regional media, although this trend did not reach statistical significance.

Figure S2 shows the percentages of citizens responding YES/NO to a direct question about secession from Spain, in a hypothetical referendum of independence, segmented by participation at regional elections (measured in CEO Surveys by individual remembrances of having voted in the last ones). There were large and statistically relevant differences between both segments under any simple Sign Test (used as an approximation), with a significance level systematically less than 1%.

4. Discussion

Five years after the failed proclamation of Catalonian independence in October 2017, the division between pro-secession and anti-secession segments of the citizenry remains mostly unchanged, although the political tensions and civil unrest that characterized the peak period of the secessionist campaign and the immediate aftermath now appear attenuated. Despite the noticeable decline in political tensions in the region, the extended longitudinal findings presented here confirm the persistence of a neat political division on the issue of secession along the lines previously shown (

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b,

2020). Though explicit support for secession has steadily decreased since 2019, family language—either Catalan, used regularly by 38% of the citizenry vs. Spanish, used habitually by 54% of the citizenry—remains as the main cleavage that distinguishes preferences for or against secession. First habitual language is thus the main distinctive feature separating individuals who harbor desires for Catalonian independence from those who are against it. The gap between them, on this issue, is very large (

Figure 2) and fully confirms other analysis that established the preeminence of such an ethnolinguistic cleavage when comparing responses at the start of the CEO Barometer series (1996) with responses obtained in 2020 (

Argelaguet 2021).

The present findings complement the pattern of variations in

national identity (“

sense of belonging”) that we documented through the mounting and culminating years of the secessionist campaign (

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b,

2020). The start of the secession push as a forceful movement separated two main periods (

Figure 3): previous and stable decades when a dual-national identity (“

As Catalan as Spanish”) was dominant and worked as an amalgamating factor within Catalonian society (

Elliott 2018), and the abrupt division and polarization induced by the protracted pro-secession campaign that moved big segments of the citizenry towards distanced and antagonistic blocks (

Tormos et al. 2014;

Barrio and Field 2018;

Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio 2021;

Balcells et al. 2021;

Merino 2022). Within the pro-secession field, the “

Only Catalan” identity became rapidly dominant, whereas a dual identity “

As Catalan as Spanish” still prevailed within the anti-secession field (

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b,

2020).

The whole pattern of

national identity variations within the main linguistic segments appear in

Figure 4 (

family language Catalan) and

Figure 5 (

family language Spanish). For the first one, there was a big change within a short period: the erosion of the dual identity (

Cat = Spn) was accompanied by a large increase in the single identity

Only Catalan. Such a national identity scaled approximately 30 percentage points in a few years, peaking between 2015 and 2017. There were, however, noticeable reversions after 2018; namely, the increase in the percentage (7.5%) of “

As Spanish as Catalan” dual identity accompanied by a substantial reduction (16%) in “

Only Catalan” identity, going down from the aforementioned abrupt high. Within the segment

family language Spanish (

Figure 5), the dual identity (

Cat = Spn) showed a small erosion through most of the pro-secession campaign but no appreciable moves towards a single identity “

Only Spanish”. There were also relevant variations from 2018 onwards, such as an increase (10%) in “

As Spanish as Catalan” (

Cat = Spn) dual identity that completely reversed the previous erosion. All these variations, supported by 52 surveys amounting to 100,038 observations, are outstanding as they reflect the evolution of national identity profiles during a period of political instability.

The patterns displayed in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show that following or not regional public media (TV and Radio stations under the control of the Regional Government, broadcasting in Catalan language only) was an important factor accentuating changes in identities in both the

family language Catalan and

family language Spanish segments. Concerning the first one, a substantial part of the citizenry with

family language Catalan (21.5% of overall population) follow the regional public media to inform themselves (

García 2013;

Valera-Ordaz 2018;

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b;

Martínez Amat 2020), and increasingly moved towards an

Only Catalan identity. The segment with

family language Catalan that do not follow the news on regional public media (13.4% of overall population) was much less affected. Concerning the other main citizenry segment, those with

family language Spanish, two trends deserve attention. First, those who preferred the regional media (12.5% of overall population) changed their national identity in the same direction as those with

family language Catalan. However, those with

family language Spanish who did not follow news through the public regional media (44.8% of overall population, the bigger citizenry segment) remained mostly stable, without appreciable changes. It is also remarkable that there were no relevant changes towards “

Only Spanish” identity.

These notorious variations in

national identity resulting from interactions between family language and preferences for following or not regional media do not prove but align with the hypotheses that the contents of public TV and broadcasting stations controlled by regional powers were a source of the distancing and polarization of audiences through the cultivation of pro-secession attitudes. We must highlight the fact that the intensification towards a single national identity, “

Only Catalan”, occurred mostly within the segment with

family language Catalan, whereas the segment with

family language Spanish, which was larger in size, did not significantly move in the opposite direction, towards a single “

Only Spanish” identity.

Figure S1 depicts how attitudes in favor or against secession from Spain were also strongly dependent on the concurrent effects of family language and regional media consumption: there were big differences in preferences for secession, in both family language segments, depending on whether or not they informed themselves by public regional media. These differences were systematic and very large (between 38% and 40% points in July 2022).

Figure S2 shows that preferences for secession were also associated with the level of political participation in the regional elections: the citizenry segment that was against secession participated less at regional elections (but not at general elections), thus confirming a trend that has been systematically found, for decades, on electoral behavior in Catalonia (

Elliott 2018;

Tobeña 2021).

The influence of partisan media on the ignition and maintenance of the Catalonian secession push was a topic of debate in Spain through the entire duration of the campaign (

García 2013;

Tobeña 2017b;

Martínez Amat 2020;

Díaz-Noci 2020;

Valera-Ordaz 2018,

2023). The present findings align with a probable biasing effect of regional media outlets as they showed systematic covariations with both national identity changes and preferences for secession.

Martínez Amat (

2020) found an intensification in the following of such regional media during the mounting years of the secession campaign, and

Valera-Ordaz (

2023), using four post-electoral surveys by CIS

7 in the region, was able to show that both support of independence and the degree of nationalistic identification with Catalonia augmented the selective exposure to such regional media (TV and radio stations, particularly). These summatory effects of family language and media-following habits probably contributed to exaggerate distinctive frames of reference on both sides of the main ethnolinguistic cleavage. TV channels, broadcasting stations and platforms that are directly or indirectly under the control of the Regional Government operate only (or mostly) in the Catalan language. This is an obvious mismatch as Spanish is the language of daily use of more than half of the citizenry, thus reflecting the operation of a “

communication bubble” that mostly nourishes a targeted fraction: those who use the Catalan language in their daily routines and obtain their opinions from such media (

Barrio and Field 2018;

Miley 2007,

2013;

Tobeña 2017b;

Cuadras-Morató and Rodon 2018). Despite unsolved discussions on the relative power of media to bias and modify political opinion, there is agreement on their strong influence upon highly segmented audiences (

Falk et al. 2012;

Quattrociocchi et al. 2011,

2014;

Shoemaker and Stremlau 2014;

King et al. 2017), or upon populations aligned through highly confronted partisanships or by forceful identity issues (

Tokita et al. 2021;

Törnberg 2022;

Valera-Ordaz 2023).

Our dataset consists of repeated surveys over time and the time dimension gives the opportunity to see the persistence of some of the covariations or group differences. A key finding was that when controlling for the essential variable, such as the ethnolinguistic segmentation, followers of regional media still showed significant differences in national identification, this difference being persistent across the years, except in the initial period of the series (when the campaign for secession was not yet initiated). Our findings do not permit conclusions on causality, but the intensity of covariations and group differences should serve to better investigate alternative hypothesis. Alternative factors and other control variables could be important, but the significant correlations and the highly visible group differences in our graphs show, we believe, the power of observational data in assessing the evolving conflict in Catalonia.

In our previous studies (

Oller et al. 2019a,

2019b,

2020), we highlighted the relevance of two “turning points” that signaled departures towards division and polarization among the Catalonian citizenry. The first one appeared shortly before the sentence of the Spanish High Court, in 2010, modifying the Autonomy Statute (Home Rule) approved in 2006. The second was the pro-secession agenda adopted around autumn 2012 by the nationalist party that had been leading, for decades, the Regional Government. In his comparison of Scotland’s lawful independence referendum in 2014 and the unlawful one in Catalonia in 2017,

Elliott (

2018) underscored the same “breaking points”. The first one contradicted the depiction of a pro-secession surge as an outrage reaction against the “deep grievance” of the sentence from the Spanish High Court, modifying a few articles in the 2006 Statute of Autonomy that had been voted for by a minority of citizens. Much more decisive was, however, the prelude of the regional elections on 25 November 2012. Such elections marked, in fact, the definitive point of departure for the secession campaign when the moderate nationalist party leading the Government lost their majority in the Autonomous Parliament. From that moment onwards, the parliamentary majority depended on various secessionist forces and the Government opted for secession from Spain as its dominant strategy (

Barrio and Field 2018;

Elliott 2018). The present extension of our longitudinal analysis to the five years after the failed independence proclamation allowed us to detect another relevant “turning point” that marked a change in the variation patterns of national identities. It was situated between 2018 and 2019 and signaled, in fact, the start of a progressive weakening of pro-secession support that was accompanied by a sustained and noticeable reversion of the antagonistic identity alignments that had characterized the political division, within Catalonia, during the mounting period of the secession bid. This “turning point” was situated around the period of the trial of several secessionist leaders at Spain’s High Court and might reflect the final appraisal of the demise of the secession push.

Through the years of the secession campaign, Catalonian citizenry gave repeated signs of perceiving the political division in a very distinctive way. More than half of them recognized the deep social fracture, but another big segment denied it outright. Such contrary perceptions have appeared in surveys, though the CEO Barometers do not inquire about this point. Voters of unionist parties typically recognized and regretted the social division, while voters of secessionist parties denied it (

Tobeña 2021). The same distinction appeared comparing the opinions of citizens with family language Spanish and those with family language Catalan (

Oller et al. 2021). This peculiar gap disclosed the existence of a large social distance that has been corroborated using polarization measures. Departing from surveys applied with one year of difference between them during the key period of the secession push (2017–2018), and from “quasi-experiments” embedded in them,

Balcells et al. (

2021) described a society with high levels of affective polarization: pro-secession and anti-secession advocates had strong negative views of one another, and there were also stereotyped attitudes towards opposing family language segments. From a series of surveys

8 during the period between 1995 and 2021,

Merino (

2022) detailed an increment in affective polarization in Catalonia that separated the pro-secession and anti-secession citizenry segments, in close parallel to the launching and peaking of the secession campaign. The increasing affective distance between pro-secession and anti-secession advocates rested on prominent identity alignments. Finally, using the results of the 2017 regional election,

Maza and Hierro (

2022) found strong polarization scores inside Catalonian municipalities that rested upon voting for either pro-secession or anti-secession parties. Moreover, family language, place of birth (ascendancy) and socio-economic levels were highly predictive of polarization degrees.

The detection, in the present findings, of steady reversions of alignments from

single national identity bastions (“

Only Cat”, mainly) towards recovering the preeminence of

dual national identities (in different degrees), which were dominant in the region before the secession push, runs in parallel with the attenuation of open social tensions since 2019. To confirm such tendencies, however, changes in polarization measures will be decisive, although CEO Barometers do not include the required variables

9. When a political conflict focuses on a nodal discrepancy such as pro-secession and anti-secession preferences, as is the case in Catalonia, the chances of digging a deep trench between two strongly antagonistic sides are very high (

Balcells et al. 2021;

Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio 2021;

Merino 2022;

Maza and Hierro 2022;

Tobeña 2021), and when that happens in a context where it is easy to draw lines of friction or cleavages that run alongside ethnolinguistic ingredients or sociocultural signifiers (language, ancestry, socio-economic status), the possibilities that such entrenched sides can get stuck in positions ready for open confrontation is even higher (

Horowitz 2001;

Esteban et al. 2012). It is good news, then, that the present findings displayed clear signals of an ongoing attenuation of both open social tensions and political divisions rooted on identity gaps.

Further and much more detailed research will be necessary to disentangle the plausible combination of ingredients that promoted the precarious but ongoing attenuation of the political division that we have detected here. There are many obvious tracks to be explored: (1) The progressive appraisal and acceptation of the “failure” of the unilateral secession bid, which was already recognized by (some) secessionist leaders and supporters after 2019. (2) The increasing discrepancies and intense fights among different pro-secession forces and activist organizations. (3) The out of the blue intrusions of, first, the COVID-19 pandemic, and subsequently, the Ukraine war once the coronavirus epidemic was fading, with their acute alarming effects and long-lasting economic impacts upon privileged and (mainly) non-privileged citizenry sections. (4) The steps (both judiciary and political) that resulted from negotiations between the Spanish Central and Catalonian Governments to redirect the clash produced by the secession push. (5) The available examples of other European segregation moves (i.e., Brexit) or secession attempts (i.e., Scotland) that have encountered increasing and challenging problems.

To conclude, the present findings confirm the persistence of a fissure between Catalonian citizenry along similar lines to our previous longitudinal studies: family language interacts with the divisive influence of regional partisan media to keep the political fracture on the issue of secession alive, though with several signs of a limited but progressive attenuation. The intrusion of two unexpected and major extemporaneous events—the coronavirus pandemic and the challenges triggered by a European war in Ukraine—probably added to the long-lasting and difficult digestion of the secession bid failure. A sum of factors that contributed to attenuate both political confrontation and social division within a conflict that has not been solved, albeit it appears mitigated and perhaps in hibernation for a while. The meandering history of the repeated but intermittent “Catalonian crisis” within contemporary Spain (

Elliott 2018) might presage that.