‘He that troubleth his own house shall inherit the wind’.

Proverbs 11:29

Academic historians have spent over two decades fidgeting a little censoriously about the critical as well as creative possibilities of genealogy. While they were cautiously testing a new resolve not to ‘sneer at the genealogists’ (

Rickard 2013, p. 462), family historians were just getting on with things. The inexorable and well-documented rise in interest in genealogy since the 1970s shows no signs of abating, from the enduring popularity of ancestry-themed TV shows to the exponential attraction of online subscription resources. The rapid growth of indexed and digitised family history resources now available to all researchers has also been due in large part to the often-voluntary labour of family historians. Authors of a 2021 collection exploring the dialogue between ‘family’ and ‘professional’ historians in Australia and New Zealand use a metaphor of confluence—‘family history is the place where two great oceans of research are meeting’ (

Allbrook and Scott-Brown 2021, front papers).

1 The reality has been more like a tidal wave which has stirred a complacent if not resistant academy into action and response; while some see recombinant methodologies as something still imminent or just about to happen—‘a prospective marriage’, notes Graeme Davison (

Davison 2021, p. ix)—many of the contributors to Malcolm Allbrook and Sophie Scott-Brown’s

Family history and historians in Australia and New Zealand attest to the extraordinary breadth of work within, between and beyond the academy that addresses historical thinking and historical consciousness as a core engagement of family history. This article enters into the debate by taking a new angle on critical family history: an angle that is both personally inflected and also shaped by theorisations of colonialism and its aftermath.

The scholarly trajectory is important for understanding why new approaches are politically and intellectually relevant as we conceive of new family histories. In 2000, Davison characterised the genealogy boom in Australia as the domain of the hobbyist and as an affirmation of stability for a predominantly well-to-do generation of middle-aged women ‘threatened by the changes of the postwar era’ and the challenges to the family of ‘mobility, divorce and intergenerational conflict’ (

Davison 2000, pp. 81–82). If the past seen from the latter part of the twentieth century was ‘consolingly secure’ (

Davison 2000, p. 83), two decades later it could play a more nuanced role in historical thinking and the construction of empathy. Davison had astutely recognised ‘the radical possibilities of family history’ (

Davison 2000, p. 98), a concept developed by Tanya Evans (

Evans 2011) and further elaborated in her most recent work on family history, historical consciousness and citizenship (

Evans 2022). In this contemporary and perhaps more optimistic version of the capacity of family history to engender empathy and rational compassion, individuals can see their extended family history as a correlate of the family of nations. To view the world through the eyes of ancestors and ‘to think like others’ is instructive in being more tolerant of difference in the present day (

Evans 2022, p. 111). Family historians, claims Evans, ‘are using their own family histories to interrogate national historical myths and storytelling to produce new versions of the past that include their family’s stories and the life stories of those marginalized by official histories, including the poor, people of colour and women’ (

Evans 2022, p. 113). Family history, in this more complex rendition, can be both stabilising and unsettling, something fixed and objective to hang on to, even to be proud of or excited about, while at the same time evoking more complex emotions of anger, sadness and shame through learning about the traumas and hardships of ancestors or the revelation of painful family secrets (

Evans 2022, chp. 3).

Affective histories play a role here, too. In the very recent work of Evans and Allbrook and Scott-Brown, two key retellings of the power of family history in contemporary Australasia, there is, still, a surprising elision around the difficult question of the liminal place where the emotions of anger or shame verge on guilt. When a descendant of Northern Irish Protestants reflects on their likely implication in sectarian persecution, Evans suggests that ‘anger can be coupled with guilt on occasion’, though its nature or limits are not elaborated (

Evans 2022, p. 68). This is perhaps an even more surprising silence in Allbrook and Scott-Brown’s collection. Multiple contributors to their volume are alert to the various stigmas and silences of family violence, illegitimacy, mixed-race relationships, or adoption. Furthermore, Nick Brodie links familial stories to national narratives of Australian history (

Brodie 2021, p. 45); Ashley Barnwell explores the political role of family histories, as the locus of collective memory, in certifying particular national narratives (

Barnwell 2021, p. 86); Anna Clark is concerned with individuals ‘connecting’ their family histories to public historical discourses and in so doing perhaps lifting the veil on understanding traumatic pasts (

Clark 2021, p. 100); Matthew Stallard and Jerome de Groot tackle the ethics of revealing clandestine stories and the delicate calibration between ‘truth-seeker’ and ‘secret-keeper’ (

Stallard and de Groot 2021, pp. 151–52); and Emma Shaw explores the ways in which family history research influences an individual’s understanding of history (

E. Shaw 2021). Nowhere in this collection, however, is there a direct analysis or theorisation of the intergenerational impact for families or their historians of the revelation of the exercise of colonial power by their forebears. Put more baldly, how might it/should it feel to have a slaver (or, for example, a missionary/plantation owner/colonial administrator) in the family tree?

Academic commentators encourage critical self-awareness along with critical scrutiny of online resources, official records and personal memories. Notwithstanding this, Christine Sleeter’s key term ‘critical family history’ is avoided in both recent books as any kind of helpful interpretive tool to examine cultural privilege, institutionalised power and structural disadvantage in a family history context. Evans acknowledges Sleeter’s work in ‘encouraging people to explore the multiple ways in which people construct their subject positions over time’ (

Evans 2022, p. 144), while Anna Clark dwells perceptively on the conundrum of balancing her own desire for critical historic practice with the need to respect the historical consciousness of her informants. Is it here in these eddying waters that the comingled ocean parts? Clark clings to the raft of ‘an edgier critique’: the ‘everyday historical understandings’, she argues tentatively, ‘are not equivalent to scholarly expertise’ (

Clark 2021, p. 107).

We could say that critical family history transcends genealogy by expanding the temporal frame of a life story beyond the static accumulation of facts and figures to an acknowledgement of context, a deeper understanding of structure, a reckoning of circumstance and response and a comparison across time and space. And we might also ask: what moral or ethical choices are made by individuals? Do individuals follow orders or buck the system? How do families benefit from the oppression or exploitation of others? What is the relationship (if any) between an individual’s position in terms of precedence or pay grade and their implication in colonial injustices? What do kith and kin do collectively to support or challenge their privilege or their precarity? Furthermore, with such information at hand, what role if any can critical family history play in atonement? If colonialism is a process rather than an event, truth and reconciliation are an ongoing calibration between thoughts and actions that occurred in the past and the moral compass of the present. What role, we might ask, does the emotional resonance of critical family history—and in particular, the notions of shame and guilt—play in postcolonial reconciliation processes? (See for example

Allpress et al. 2010).

For academic historians, writing publicly about our own ancestors, as Kendra Field has so eloquently articulated in a recent article on ‘The privilege of family history’, is a relatively recent phenomenon and one loaded with complexities of methodology and objectivity as well as the challenge of writing ‘unflinchingly’ about difficult pasts (

Field 2022, p. 631). American historian Joe Amato’s

Jacob’s Well: A case for rethinking family history (

Amato 2008) was an exemplar for all historians developing national stories using their own family history as both subject and method. In mapping his own family history across seven generations as a microcosm of the American national story, Amato crystallised what he called ‘the trinity of family history’—genealogy (‘You can’t tell the players without a program!’), history (local, micro-regional, national, macro-regional, international) and storytelling (stories ‘provide the richest clues and deepest enigmas’). As much as anything, Amato ‘had to discover and invent them, remember and resurrect them, and yet beyond the cultivation of their meaning give them control over their own lives’ (

Amato 2008, pp. 10–14). In Aotearoa New Zealand, Jane McCabe’s important study of transnational family histories, inspired by the ‘pronounced silences’ surrounding her grandmother’s Anglo-Indian origins, problematises the role of archives and connects private stories with national and indeed broader imperial narratives (

McCabe 2017, p. 1). More recently, political scientist Richard Shaw has exemplified this newer genre of self-reflective and more critical family memoir which attempts to right the wrongs of ‘orthodox settler narratives of “success, inevitability, and rights of belonging”’ and to ‘end that forgetting’ (

R. Shaw 2021a, p. 1). Shaw’s book

The forgotten coast engages provocatively with his Irish-born great-grandfather Andrew Gilhooly’s involvement in the violence of colonial rule. For Shaw, ‘the need to understand is a compulsion rather than a pleasure’ (

R. Shaw 2021b, p. 15), a decolonisation of memory being fundamental to the politics of apology (

R. Shaw 2021a, p. 11).

My own history of the foundation years of the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist Foreign Mission to the Khasi Hills of north-east India, while less consistently structured as a family history per se, was dismissed as a vanity project by more than one academic colleague as ‘that little book about your great-great-grandfather’ (

May 2012). Opening doors on troubled pasts can disturb a multitude of houses, whether institutional, personal, or communal. There is a fine line to be drawn between self-indulgence (often avoidant of conflict, and perhaps self-absolving in its tendency to overlook the unequal consequences of power or privilege) and self-critique (which risks indulgence if it runs to self-flagellation, but is a difficult and indeed courageous necessity for clear sightedness in the shadow cast by colonialism). In the academy, there is often some bemusement about what are often seen as the ‘side projects’ of mature scholars turning towards self-discovery, as much as work that represents a serious intellectual pursuit. In other ways, my deeper and ongoing forays into the complex intercultural histories of colonialism in north-east India have the capacity to disturb intimate understandings of my own family’s history, unsettle the nostalgic histories of cognate communities of interest who have a collective present-day stake in how these memories are mediated, as well as being agitations in broader cultural debates over the heritability of colonial guilt (

Shriver 2022). This article offers a reflection on the complexity of exploring family history in the context of colonial pasts; the possibilities offered by group or cohort analysis of colonial actors; and the moral obligation of the historian, as Greg Dening insisted, to return the dead their present, to humanise rather than prejudge, and to bring our own humility and ‘hindsighted clarity’ to their reckoning (

Dening 1996, p. 204). In this way, the unpleasant truths uncovered through family history stimulate a conversation about complex histories which may have redemptive possibilities rather than triggering a brusque and brutal accusation that forecloses them. In the specific context of migration history, I draw especially on the work of

Lucassen and Smit (

2015) in insisting that historians embrace ‘the repugnant other’ of colonialism—the soldier, missionary, diplomat or scholar—in the category of ‘migrant’ and as a serious object of study, however incongruous they may appear in a new social history paradigm that has favoured the marginal and subaltern.

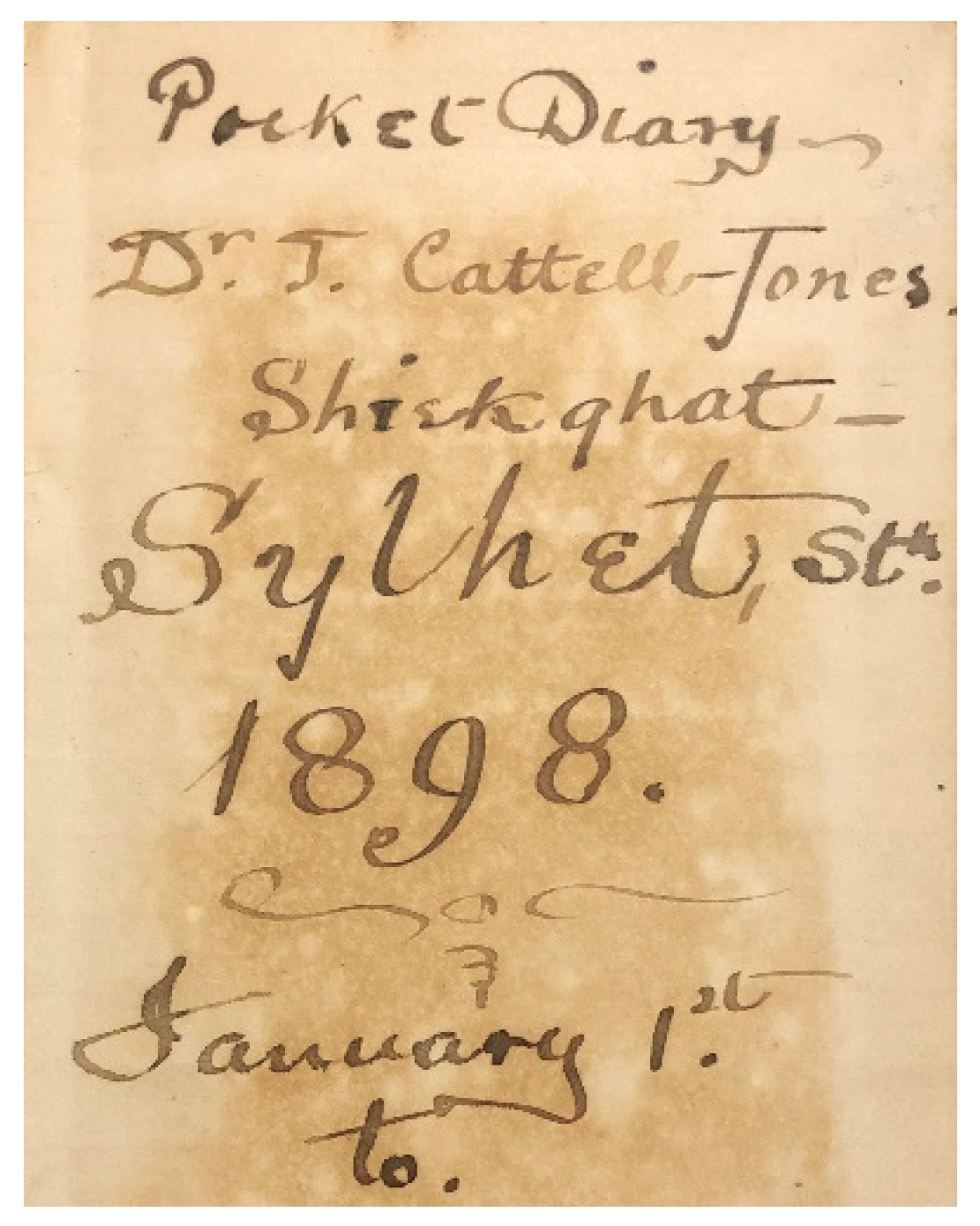

A diary, a database and a story that may or may not be a parable, serve here as my points of departure to find meaning in the contested terrain of family history. On the desk as I write sits a small black leather-bound pocket diary, the majority of its hundred or so pages blank (

Figure 1). It is one of the very few old family mementoes inherited from my late mother, a descendant of Welsh missionaries to British India. Like many family heirlooms in general, it has a particular migratory history of its own that transcends individual lifetimes but binds intergenerational memory and storytelling. An inscription in ink on its title page sets out an aspiration for its future contents as much as an assertion of ownership and location in a particular time and place. January 1898, after all, was just six months or so after the catastrophic Assam Earthquake of 1897, its epicentre in Shillong in the Khasi Hills, estimated to have measured around 8.3 on the Richter scale and which laid waste to an area the size of England.

Pocket Diary~

Dr T. Cattell-Jones.

Shiek ghat—

Sylhet Sth.

1898.

January 1st

to

If you turn the diary around and read it from the back, two pages of unofficial business is recorded in a brief list of presents for children.

For Margaret

A large baby doll dressed like a baby.

Chocolate creams.

Dolls [wash stand] with basin …

Bible for birthday

For Glyn

A tool box.

Leaden soldiers & a cannon

For Llewellyn

A football with pump

A penknife with several blades

Large marbles.

The bible and the cannon were different and at times complementary colonial means of changing hearts and minds; here, itemised in a list of presents for my great-uncles and aunts, was empire in all its gendered construction, ideological meaning and martial might. The diary itself contains only a dozen or so small pages of pencilled scrawl which records the medical notes of a vaccination program in the region of present-day Sylhet (now in Bangladesh, then in British India), until another’s handwriting takes over:

Thursday 10 Feb 98

To Kallagool

11th At home all day

12. Taken with watery purging gripy early in the morning. Nellie & Mr Jones came also Dr Banerji. Choleraic attack continued all day, could not get him warm in spite of stimulants & rubbing dreadful cramps & collapse, took everything that was given him but gradually sank & died about 4 am Sunday morning my dear good kind gentle patient husband.

Jean was a great-grandmother I never met; Thomas her dying husband. This passage, therefore, no doubt moves me much more than it moves you. At worst, reading other people’s family histories tends to make one’s eyes glaze over. But, at their best, their latent power is in their provocation; my family history invokes a reflection, however passing, on your personal history. Each separate genealogy invites a collateral reckoning of the past on another’s terms, peopled with other ancestors, furthered with different stories. If they are critical family histories, even more so.

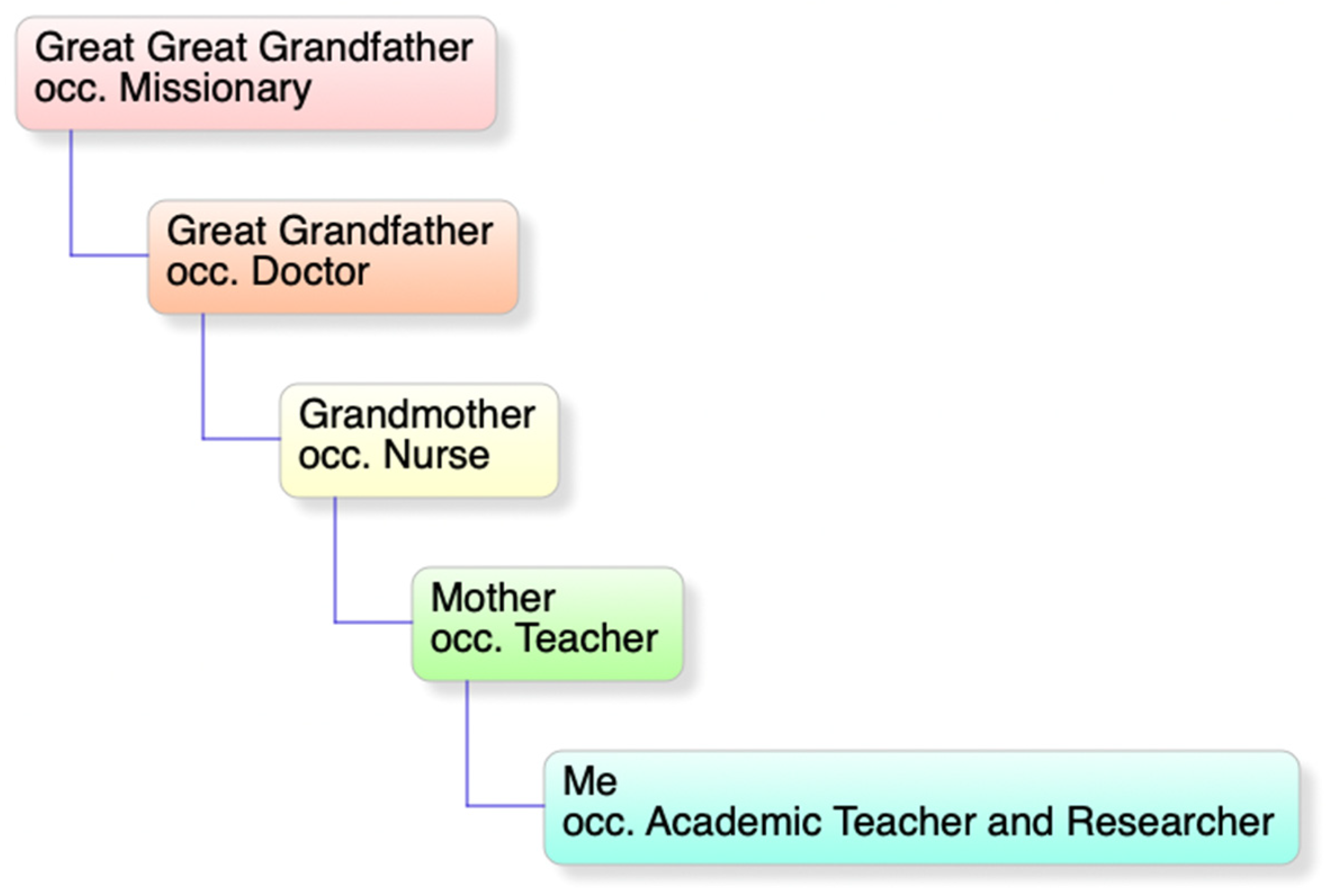

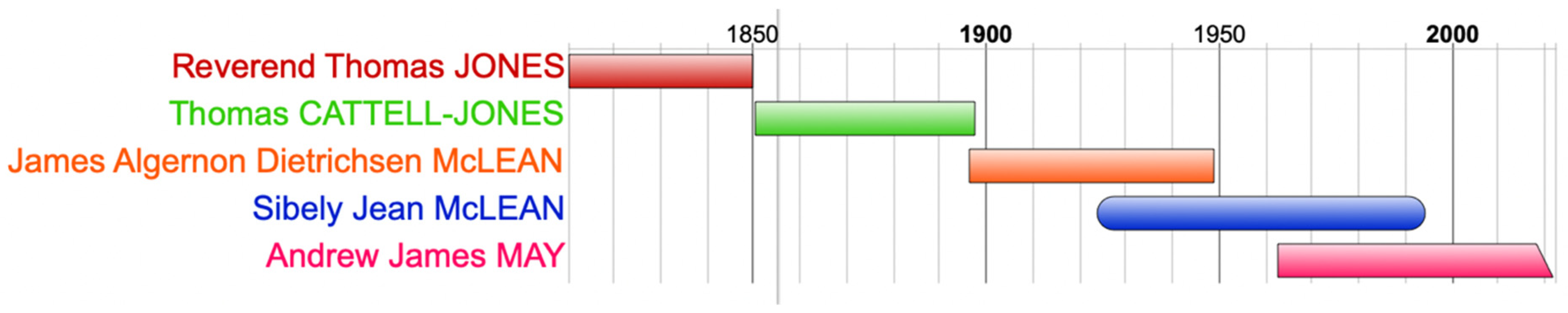

In the literature to date, critical family historians often start from their own subject positions; ostensibly, to unsettle their own assumptions and to establish the terms and scope of a new inquiry. My own genealogy places me in a particular time and place in the British Raj in India, that in turn sends shockwaves to the present day. The diary’s owner, for just a moment prior to his demise, was Dr Thomas Cattell-Jones, born in 1851 at ïing maw (the stone house) in Cherrapunji, now officially renamed Sohra (its original Khasi name) and since 1972 situated in the northeast Indian state of Meghalaya. Thomas’s grieving wife Jean, who glossed his deathbed scene, was born at the mission bungalow in Sylhet in 1858. Thomas was the son of Thomas Jones I, the founder of the Welsh Calvinistic Methodist Mission to the Khasi Hills (1810–1849); Jean the daughter of Thomas Jones II (1828–1874), also a missionary in the Khasi Hills. Both Thomas Jones I and Thomas Jones II, as it happens, were expelled by the mission authorities for various perceived misdemeanours, and further expunged from many of their historical accounts, both dying in India of disease.

The last missionaries quit India in the decades after Indian Independence in 1947, but Meghalaya is not the India which is conjured up in the minds of most non-Indian readers. The Khasis are traditionally a matrilineal and animistic hill people, although Christianity now predominates (74.5% in 2011, compared with 11.5% Hinduism and 4% Islam). Reception of my 2012 history and reckoning of the life and work of Thomas Jones I—my great-great-grandfather—was at times frosty. Some (though I hasten to say not all) in the Welsh church condemned me to outsider status, branding me ‘a secular historian from Australia’ who ‘sees the Christian mission working hand in glove with the British Empire’, and imposing ‘the secular and suspicious questions of the 21st century’ on the brethren of the nineteenth who, after all, were simply ‘the products of their age’ and left a lasting legacy of good works (

Jones 2013). Other individuals in the Khasi Christian church (with notable exceptions) wondered why I was so critical of their founding father, the bringer of their religion and, as the first to translate the Bible from English into a written Khasi language, the zero point in their transition from oral to written culture.

My critical analysis of colonial sources is both implicit and explicit: that British characterisations of the Khasis were culturally absolutist, superficial, racist and ignorant; that their letters and journals were ideologically driven in the cause of their visions of science, nature, power, gender, politics and resources; that missionary accounts elided indigenous agency in the translation process; that reading between the lines of the hegemonic colonial archive can reveal deeper aspects of agency, belief and cultural practice; that power relations are revealed through a careful analysis of the structures of epistolary practice; that scandal, gossip and archival manipulation all play a role in mediating the actualities of the past; and that local British courts were often corrupted by the nepotism of colonial officials and biased translators. While generally favourable to my contribution, some scholarly reviewers insisted either that Welsh missionaries in general were unfairly portrayed in my book due to a lack of attention to missionary correspondence; or in contrast, that my use of the missionary literature was deployed in an uncritical way (

Aaron 2016, p. 195;

Ray 2013, p. 12). The churches in Wales and in India deprecated my attempt to write about

their history; I considered I was writing in a nuanced, self-reflective and sensitive way, informed by critical race and gender theory, about

mine. If my work is a kind of critical family history, however, it requires a two-way dialogue where ‘critical’ invites further analysis, commentary, judgement, even censure from my reader. Family stories, warns Richard Shaw, ‘can also be dangerous—far from anodyne and never neutral. They are a sort of public property: some are more or less sacrosanct, while others are battle sites, fiercely contested. These you tangle with at your peril’ (

R. Shaw 2021b, p. 19). The evaluations of others may or may not align with my own informed but always limited viewpoint. It is in this way that critical family history might be respectful, adaptive, co-produced and co-dependent.

The story, that may or may not be a parable, concerns Thomas Jones I, who, after the death of Ann, his Welsh-born wife, married fifteen-year-old Emma Cattell (my great-great-grandmother), though he is said in local lore to have married a local girl. While my research shows the latter to be unproven in any documentary way, there is always the chance he had a relationship with a tribal woman.

2 But the origins of the legend might best be explained by lexical particularities—‘Ka’ being the feminine article in Khasi, making ‘Ka Tell’ sound a plausible native name. The fact that Thomas Jones had been expelled from the mission in 1847 and supposedly ‘gone native’, defending the rights of ‘his’ people in the face of British violence and exploitation (from nepotistic and unrestrained legal, political and commercial interests), might underscore the durability of his status as both a religious and a secular figure. He loved us, Father Sylvanus Sngi Lyngdoh once told me in Shillong. He esteemed us. He was almost one of us, hence the tale that he married a Khasi girl, and ongoing ‘Indianised’ versions of his image (

Figure 2).

Engaging in critical family history, however honestly, may ruffle feathers (See for example

Freeman 2021). So it should. But is there more to be said about a subtle and caring approach that moves beyond a censorious ‘it’s the right thing to do’ to a more coherent, thoughtful and workable methodology of truth-seeking, even reconciliation? Reduced to the history wars, contested debates about whether colonialism was a good or bad thing may seem irreconcilable. Critical family history, however, brings with it both an individual substrate for building narrative connection, as well as the capacity, if not necessity, of holding two or more thoughts or feelings in our head at the same time about our ancestors. Reflecting on the moment when Thomas Cattell-Jones was feverish with cholera and drawing his final breaths—in that room, on that day, in that place, at that time—I feel desperately sorry for Jean, his scared and loyal wife. I also know that while they both rejected the formal missionary structures of their respective parents, they were heavily implicated in the structural oppression of native peoples through this period of the British Raj. The one does not discount the other; indeed, because they are human, they are mutually constitutive. Thomas worked as a doctor on tea-estates where coolie labour was exploited in the service of British economic interest (

Sharma 2012). Thomas and Jean had lost all their worldly possessions in the earthquake in June 1897. Jean then lost her husband in 1898, four of her nine children having succumbed to cholera or typhoid in the previous three years: George in Dum Dum in 1895 aged 2, Evan there in 1896 before his first birthday, Thomas and Rachel in Sylhet two months apart in 1897 aged 10 and 8, respectively. Thence the widowed Jean and her five surviving children (including my grandmother Gwen, great-aunt Margaret and great-uncles Oliver, Glyn and Llewellyn) found their way to Kalimpong where she became the first housemother at the St Andrew’s Colonial Homes (later known as Dr Graham’s Homes), an orphanage for mixed race children, many of tea-planter fathers and Indian mothers.

3Within the walls of my own family history, therefore, data provide the framework, but stories furnish the house and titivate the past with special curated meaning. Descent lines inexorably lead from one individual in the past to another in the present, but the selectivity of the perspectives thus produced demands cautious contextualisation. In the trees that we can export from our genealogical software we see more than individual datapoints and gloss their certainty as facts with fables that may be less certain. Our propensity to want to seek kinship affinities in terms of characteristics that may have been passed down the line from our forebears (personality traits as much as physical resemblances) is complicated by the extent to which they are socially constructed as well as genetically determined. I was astonished when my mother, poring over the ultrasound scan of my unborn daughter, casually commented that she had auntie’s nose. Maybe she did; but my mother’s comment also served an important kinship function in rooting herself (and me as well as my offspring) in a particular version of our family’s past. As Jennifer Mason notes in her typology of four types of affinities (fixed, negotiated and creative, ethereal and sensory), ‘there are creative opportunities for people to actively engage in how they are connected to others’ (

Mason 2008, p. 32). Such fascinations make us human; Matthew Elliott notes that it is normal ‘to make explicit choices about the information uncovered and whether it will be noted, remembered, or possibly incorporated into one’s sense of self’ (

Elliott 2017, p. 76). But in the case of ‘the inconvenient ancestor’, Elliott also explores the ways in which selective genealogy (in the context of genealogy television) runs the risk of evasion, contradiction, even fabrication. In blurring past and present—as subjects seek to affirm facts about their own values, identities, or beliefs—the inconvenient ancestor shuffles on and off stage either as an exception to the rule, or a character whose dastardly deeds can be mitigated by stories of alternative ancestors with redemptive narrative ballast. Rehearsing Edward Ball’s ethical position in

Slaves in the family, Elliott eschews any insistence that descendants have any culpability for the acts of long-dead ancestors, but insists on their need to be accountable, where accountability equates to a responsibility when ‘called on to try to explain it’ (

Ball 1998, p. 14).

First welcomed to the Khasi Hills in 2004 as a direct descendant of Thomas Jones, my subsequent task was to explain what he thought he was doing there in the 1840s, what he did, and what ramifications this may have had for the cultures and critical identities of both Wales and Meghalaya. Every other descendant of Thomas Jones (and there would be over a hundred by now), whatever their affinities with him, may have a different version of this story to tell. The intergenerational patterns that

I discern have little universality (

Figure 3).

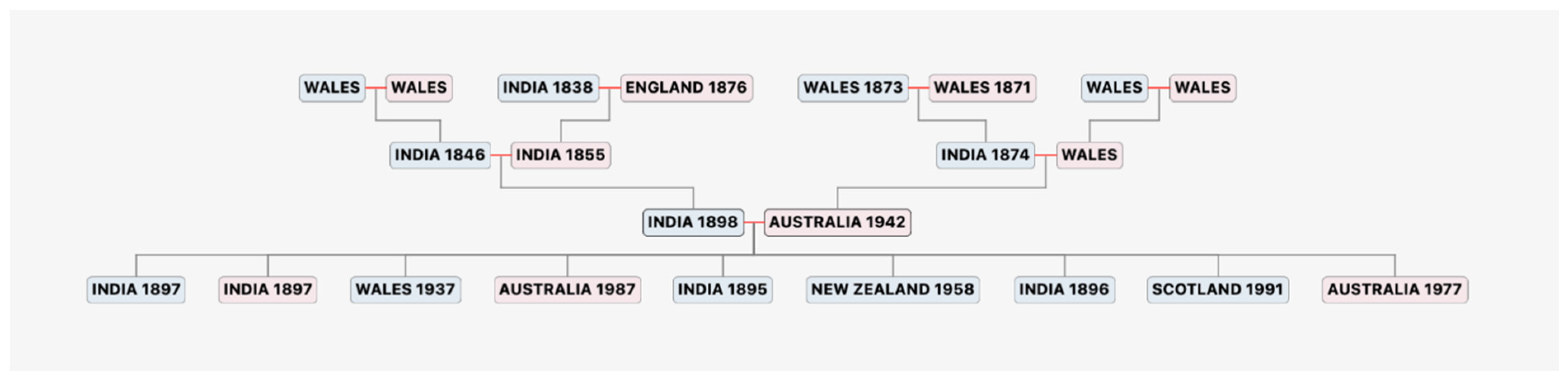

With its comings and goings, furloughs and re-postings, a colonial career is perhaps more akin to sojourning, though it often leads to a diaspora of sorts, or at least a dispersion, and not always a ‘homecoming’. Furthermore, while organisational migrants can easily be characterised as tools of imperialism, their capacity to exercise agency over their ultimate mobility, as Lucassen and Smit attest (

Lucassen and Smit 2015, p. 6), sits on a spectrum between voluntary and forced. Periods abroad reveal patterns of behaviour and habits of mind: a destabilised sense of ‘home’; a deracination from extended blood family; a disconnection from culture, the corollary of which becomes forms of expatriate bonding; an invention of tradition; even a remodelling of identity. Thomas Cattell-Jones’s family serves as a small example. He was born and died in India, though was sent back to Britain to be educated. His widow Jean drew on networks of family, association, religion and employment to ensure her Indian-born children could survive and hopefully prosper. Oliver was sent to Wales aged 11 to be brought up by his mother’s cousin, going on to graduate from Bangor University and becoming a school teacher; Glyn was a tea-planter in India and retired to Scotland; Gwenllian and Margaret were sent to the Home School for missionary children in Edinburgh, becoming, respectively, a nurse and a teacher and spending most of their adult lives in Adelaide; Llewellyn was sent to New Zealand with a batch of Dr Graham’s Anglo-Indian children, fought in World War I, never married and died in straitened circumstances in Christchurch in 1958. A table of place of death maps out constituent identities across time, fractured by intergenerational seams, fusions and fractures, amalgams and re-combinations (

Figure 4). Three generations of children grew up not knowing a father, who either shortly predeceased their birth or died before they reached adulthood (

Figure 5).

When I was young, I always saw my mother Sibely McLean as being intrinsically ‘Scottish’ (born in Helensburgh; antipathy towards the English; daughter of a Scottish farmer turned mechanic from the Isle of Bute), and my grandmother Gwenllian Cattell-Jones as ‘Welsh’ (her name; granddaughter of a well-known Welsh missionary). Critical family history combined with a consideration of migration patterns has revealed the contingency of such constructions of identity. The family photograph of my mother in a suburban Adelaide backyard in the 1930s—a young girl in Welsh ‘national dress’: tall black chimney hat over white cap, white blouse, check skirt—is a fantasy of affinity (

Figure 6). My mother only ever lived in Scotland for the first four years of her life; my grandmother, born in India, sent to Edinburgh for schooling around the age of 15, and migrating to Australia with her husband and young daughter in 1928, never, to my knowledge, lived in Wales at all. My study of Thomas Jones the missionary started with family stories, but ultimately demanded that I engage with place, peoples and their postcolonial present in Britain as well as India, and negotiate a continual juxtaposition of my insider/outsider status among multiple constituencies (one of us/one of them), all of which have engendered humility and required humanity. As a historian less comfortable with theory and more concerned with how the past makes us feel in the present, I have chosen to sit in a somewhat exposed territory, the middle ground between the extremes of hagiography, the blunt orthodoxies of postcolonial dogma, and my own imperfect aspirations for post-patriotic history making (

Drayton 2011).

Through the migratory and migration stories of my own emissaries of empire—the dislocated people, objects and memories that sustain and refashion adherence and identity—a longitudinal dimension is added to family history; an acknowledgment of privilege, as well as the relativities of opportunity or adversity in lives lived. Migration in this sense is a long process of coming to terms, with past inheritance, dislodgement, as well as future status and prospects. As Jane McCabe has argued in relation to mixed-race Anglo-Indian migrants, their reception in the Australasian colonies cannot be fully understood without a commensurate analysis of the socio-politics of their Indian origins (

McCabe 2014, p. 45). After a 1947 Commonwealth conference, the former colonial status of ‘British subject’ was replaced with new citizenship requirements in Britain (British Nationality Act), Australia (Nationality and Citizenship Act) and New Zealand (British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act). Stricter measures were also subsequently applied to ‘British subjects’ seeking entry into Britain from other Commonwealth countries. In 1961, when my great-aunt Margaret Cattell-Jones applied for the pension in Adelaide, ‘The magistrate … even questioned her right to call herself a British Subject as she was born in India!! Poor Aunty was terribly upset when she came back … She also told him that there was no question of her not being a British subject when she entered Australia 33 years ago!!’ (

McLean 1961). While her mother Jean had played a colonial role as housemother at Dr Graham’s Homes earlier in the century, those mixed-race children who fled India after Independence in 1947 could fall further through the gaps of official as much as personal acknowledgement (

May 2013). Quitting India meant precarious migratory trajectories to Britain, Canada, New Zealand and Australia for a stigmatised Anglo-Indian community. To be admitted to the imperial diaspora, old boys and girls from Dr Graham’s orphanage desperately sought paperwork to prove that at least one side of their ancestry was European. Tom C. hoped to find a birth certificate to prove that his English father worked on a tea estate in Sylhet, Assam: ‘If I can get my fathers Birth Certificate, like many have done, I may be able to ‘WANGLE’ a British Passport’ (

Tom C. 1950). Donald met up with an uncle in England in 1950 but was quickly disowned: ‘I have heard no more from him. Obviously he’s not interested so I shall not pursue the matter further. The sins of the father certainly weigh heavily on the unfortunate children in many aspects of life. However, one must continue to try and live a clean honest life trying to repay good for evil’ (

Donald 1950).

My interest in Shillong and the Khasi Hills in the period my own family worked in Assam is personal, but also helps me understand the broader dynamics of empire and colonialism. What more can we learn of this colonial context by expanding the critical family history framework from a single family to a cohort perspective? And is there a link between the personal and a wider critical perspective? My current project,

Becoming Khasian, is a study of power and identity in the experience and effects of British colonialism in the Khasi Hills in the period 1880s–1920s: the high point of missionary endeavour and its corollary, the burgeoning of Khasi resistance and cultural efflorescence; a profile of the British hill station of Shillong, the capital of the British province of Assam, as a bastion of British ideology; and the engagement of Khasi Labour Companies by imperial forces in World War I. We know a lot about families in British India in terms of their group characteristics as well as aspects of family and social structures—either implicit in general social histories of the Raj (

Gilmour 2005,

2018); biographies including the Kipling literature (

Allen 2007); studies of particular employment categories such as missionary, administrator or soldier (

Holmes 2006); or explicit in studies of the family, women, motherhood, fatherhood, children, orphans and vagrants (

Barr 1976;

Arnold 1979;

Macmillan [1988] 2018;

Procida 2002;

Buettner 2004;

Brendon 2005;

Ghosh 2006;

de Courcy 2012;

Robinson and Sleight 2016;

Sen 2017;

Nath 2022).

A special issue of the

Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History investigating ‘family’ and ‘empire’ as contested categories collected together important work on the mechanisms through which empire ‘could operate as a key sinew of family’ and the ways in which ‘imperial processes remade relations and created new ones’ (

Cleall et al. 2013). Informed by the general histories of the Raj, I can hazard a guess at the lives of the individual British agents in Shillong over a certain period, but how much more useful would a critical family history reaching into prosopography of its British population be in revealing the more complex group and intergenerational structuring of power?

This is not to say, of course, that everyone is related to everyone else, though conceptually they may be of a

kind (OE

cynn, kin)—a group of people sharing similar characteristics. Power resides in relationships—familial but also, importantly, social, sexual, economic or political, and strongest perhaps when they are all the above. Those family historians whose interest merely extends to compiling trees simply cherry pick from databases, increasingly electronically aggregated, to source the vital records needed. They are, after all, fundamentally and logically interested in their own family tree and its branches. Historians of imperial places, relationships, or processes, furthermore, tend towards case studies or select serial analysis to exemplify broader concerns. A comparison of several studies of the

memsahib—the wife of a British official in India—reveals a standard repertoire of themes as well as sources. In the 1980s, Margaret Macmillan approached her study of

Women of the Raj through chapters from ‘The Voyage Out’ and ‘First Impressions’ to ‘Courtship and Marriage’, ‘Children: Outposts of Empire’ and ‘Housekeeping’. Mary Thatcher’s

Respected memsahibs (

Thatcher 2009) anthologised the lives of twenty women, drawing on cognate themes of travel, sport, furlough, domestic life, travelling, children, visiting, social life and health (

Thatcher 2009). Most recently in this vein, Ipshita Nath subtitles her chapters around such topics as ‘Nostalgia, boredom, marital strife, and “going native”‘, ‘Scandal’ and ‘Dirt, disease, and doctorly memsahibs’. Around half of the ninety or so primary texts drawn on by Nath also appear in Macmillan’s study over three decades earlier. In their own different ways, therefore, historians of all kinds are constrained either by their limited knowledge of sources or the limiting tropes of their genres that fit the past into a pre-determined mould. Neither of these approaches is fundamentally flawed; yet both can obscure the historicity of events and the actualities of past lives lived.

A genealogical database of British (and some other European) officials who lived and worked at the hill station of Shillong in north-east India in the 1880s and 1890s can be compiled from a range of data sources including Thacker’s Indian Directory, the official India Office List, military records, British census records, India Select Births and Baptisms (1786–1947), Marriages (1792–1948) and Deaths and Burials (1719–1948).

4 English newspapers published in India—in particular, the

Englishman and the Lahore-based

Civil & Military Gazette—also published personal columns, summaries of professional postings, as well as regular reports on hill-station society. A database thus constructed includes a few of my ancestors (including the Cattell-Jones family). However, a more complex and inter-related set of individuals connected by their role in colonial service also appears: soldiers, administrators, missionaries, businessmen, scientists, engineers, pastors, surveyors, clerks, spies and merchants, along with their wives and families, and also individuals who may be unrelated by blood ties but present in time and space and having other associational connections in communities of non-genetic kin. In any one year in the sample period, for example, there may be around a hundred or so identifiable Britishers, in addition to their wives and children. Taken collectively, the family history of a domiciled British community in India reveals not just blood ties (which are important), but critical associational links and shared characteristics that structure experience and prosper cultural coherence and practical survival: group memberships (for example, of gymkhana clubs, freemasonry lodges, professional societies, or amateur theatrical companies); marriage witnesses or bridesmaids (ritual moments that tie people in time and place and reinforce sentimental attachment and other vectors of obligate relationship); giving the name of an admired friend to a baby (consolidating friendships or patronage); the number of British officials who also had a father or grandfather in India (determining the inter-generational reach and influence of colonial service); trajectories of furlough or retirement after service (giving Indian names to their English cottages; representing and reproducing colonial knowledge and racial ideology through local society memberships or lecture tours). Seen in the round rather than in isolation, an aggregation of critical family histories may shed new light on our knowledge and understanding of colonial trajectories, motives and relationships and refresh old stories of stereotypical structural privilege.

The family history of William Rossenrode, as one example, exemplifies some of the rewards of this approach. Virtually every house in Shillong was reduced to rubble and ruin by the great 1897 earthquake, one of the biggest earthquakes in recorded history, which killed an estimated 1542 people across Assam. Robert Blair McCabe, I.C.S. (Inspector General of Police, Registration and Jails, Superintendent of Stamps and Commissioner of Excise), was crushed to death aged 43 (

Homeward Mail from India, China and the East 1897). McCabe had married Mabel Faulknor in 1887, daughter of General Jonathan Augustus Spry Faulknor, who had served in India since 1840 and whose family featured several generations of Royal Navy officers. Mabel was not allowed to mourn her husband in the quake’s immediate aftermath: ‘it wd have been so terrible, they could not get a coffin so he was buried only in a sheet & the grave was full of water. The men said they had never seen such a terrible funeral’ (

Sweet 1897).

The task of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India was to fix terrain and territory, thus stabilising knowledge and asserting control. It is something of an irony, therefore, that the second British casualty in the Shillong quake was also a retired surveyor, William Rossenrode. The role of surveyors was critical to the British imperial project. Territory visualised on a chart was an important tool of imperial acquisition as well as a potent symbol of its aspirations. The topographical features delineated on British maps, as well as the void and edge of cartographic representation, sought to fix an assured idea of place and thereby the possibility of its conquest, governability and commercial potential (

Edney 1997;

Mukherjee 2021;

Simpson 2021). Surveyors working on the Eastern Frontier series included Charles Richard Lane (1817–1883), William Charles Rossenrode (who assumed control from Lane in 1865), Henry Beverley and junior assistant Angelo De Souza. Lane and Rossenrode had worked together on the western section of the Great Longitudinal Survey in the early 1850s (

Markham 1871, p. 93;

Phillimore 1968, p. 510), and Rossenrode’s father William (1791–1853) had been an assistant surveyor to Everest in the 1820s. The Assam survey parties were beset with sickness, and the climatic conditions and jungle-covered mountain terrain complicated their task. The recess quarters at Cherrapunji, the wettest town in the world, provided some steady ground amidst the shifting clouds and dense jungles of the north-east. Surveyors’ wives, genealogy reveals, anchored themselves to the nearest suitable station to their husbands’ pursuits. Lane’s wife Jemima, and Rossenrode’s wife and family featured regularly in letters written by Emma Shadwell, the wife of another Cherrapunji official, John Bird Shadwell (Assistant to the Political Agent), discovered through the genealogical research of a descendant. William Rossenrode had married Eliza Jeffries at Kidderpore in 1858, and the birthplaces of their three children—Laura at Cherrapunji 1860, Ada at Sylhet 1862 and William at Cherrapunji 1866—mapped on to his survey territory and spoke to the peripatetic life of officials and their families. Baby William took the second name Shadwell after their Cherrapunji friends, just as William senior’s brother Samuel Peyton (born and died 1832) was named for his father’s survey colleague J. Peyton.

William and Eliza’s baby Ada did not live long and was buried at Cherrapunji on 28 May 1863. We know this through vital records; we feel its personal ramifications in other sources. Emma Shadwell sent four of her children, the youngest aged 6, back to England in 1862 while she and her petty official husband continued to work in India in the hope of being able to afford to return. The correspondence between Emma senior and Emma junior was premised on imperial power and often described its everyday imbalances and abuses: Khasi ayahs employed as nannies; British soldiers suppressing ‘rebels’; native prisoners cooped up in jail perishing from cholera. Her letters to eldest child Emma also express empire’s penalty of loneliness and illness, and a mother’s maternal feelings for an absent child. Their separation extended from months to years—Emma senior eventually died in Jowai in 1870 aged 44, never seeing her children again.

Emma Shadwell’s letter from Cherrapunji to her own daughter on 21 May 1863 frames infant vulnerability on the British frontier as well as the precarity of the surveyors’ wives; we read in it the knowledge of what happens to Ada Rossenrode just seven days later.

Mrs Lane & the Mrs Rossenrodes are still with us & I think they will be here till September as poor little Ada is still very ill last week I really thought she was dying she appears a little better just now Mr Rossenrode is expected here about the 30th of this month. Ada has just cut two teeth double she has only seven altogether & has suffered so very very much dear little Lily has seven also & has not had a days illness. I feel very very thankful that she cuts her teeth so well Indeed I have a deal & great deal to be thankful for the Lord is very good & merciful to me & mine May he give us hearts to love & please him more & more every day we live oh my Emma my own sweet child love the Lord with all your heart strive to please him in all that you do.

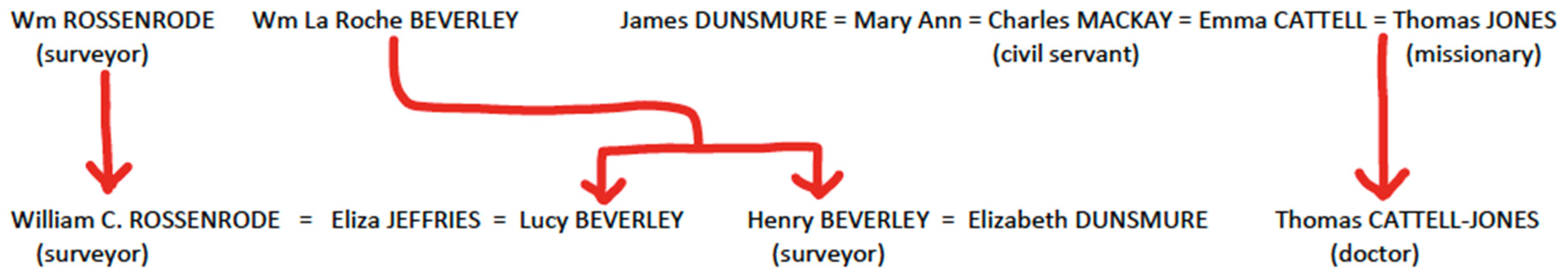

A month after giving birth to William Shadwell Rossenrode in May 1866, 24-year-old Eliza Rossenrode herself succumbed to illness and was put to rest on the small cemetery knoll at the head of the Cherrapunji plateau. William married again in 1871 to Lucy Beverley, the sister of his survey colleague Henry (b. Dinapore 1838, d. Shillong 1880 aged 41), but she too was dead by 1885, buried in Shillong aged 43.

5 Henry Beverley married Elizabeth Dunsmure (b. Bengal 1836–1908) in Calcutta in 1864. Elizabeth’s father James Dunsmure married Mary Ann (1817–), who after James’s death married Charles Mackay in Calcutta in 1840. On Mary Ann’s death, Charles Mackay (a Bengal Civil Servant, Principal Sudder Ameen of Furreedpore) married Emma Cattell at Cherrapunji in 1850, my great-great-grandmother and the widow of missionary Thomas Jones. Emma died in 1855 a month short of her 25th birthday and was buried at Dacca (

Figure 7).

A critical family history approach connects individuals along lines of blood and association; tracks mobility in the context of organisational migration (station, translocation, dislocation); explores the capacity of webs of empire to entrap as well as facilitate movement; and ultimately builds a richer understanding of the imbrication of each in the imperial project. To explore the role of surveyors in British India simply through the records of their official professional activities would be to elide a critical optic on the ways in which India was understood, ruled and experienced. To understand the frontier in British India, furthermore, is better understood when familial and associational ties are added to meta-analyses of the political ideologies of rule. The colonial frontier is usefully understood through a close reading of the techniques of ‘surveying and spatial knowledge’ (

Simpson 2021, p. 114); but it is better understood when its individual practitioners are socially contextualised.

Threaded through the regular demonstrations of play and display, Shillong’s clannish social network was reinforced by underlying and interpenetrating associational connections along lines of kith, kin and colleague. The social spaces of the playing field and polo ground, the ballroom and billiard room, the Institute and the Club, were as essential as the built form and fabric of government office, dâk bungalow, cutcherry and courthouse in structuring British rule. The careers of Colonel Robert Gosset Woodthorpe of the Survey of India and Major Francis Cracroft Colomb, 42nd Gurkha Rifles, for example, are given additional heft when analysis of their gazetted professional roles is supplemented with a study of their interpersonal relationships, particularly through their role as stalwarts of amateur theatre. Colomb had received his first commission in 1881 and served with the Burmese Expedition (1885–1889). In May 1890 he was detailed for employment in the Intelligence Department of the Quartermaster general’s Department at Simla, and married Mary Hilliard there later that year. Mr and Mrs Colomb appeared regularly in the cast list of the Simla A.D.C.; Edward Buck’s 1904 Simla, past and present recalls that Major Colomb and Colonel Woodthorpe had both ‘rendered yeoman service’ to the reputation of the Gaiety. They were clearly known to each other in cultural circles as much as through their clandestine intelligence work; they both exhibited paintings at the Simla Fine Arts Exhibition of 1892 and were members of Simla’s Himalayan Brotherhood Lodge. Colomb accompanied key British intelligence agent Ney Elias on the Siam Commission to the Shan States (now northern Thailand) in 1889, later exhibiting some ‘nicely painted sketches of the country visited’ at the art exhibition. Nearly a hundred men attended the Fancy Dress ball at Simla in late 1891, the vast majority either in their own uniform or from the stock wardrobe of eighteenth-century gentlemen, knights templar or Louis 14th court dress. Needless to say, the intelligence officers stood out like a sore thumb: Woodthorpe came as a Cossack Chief, Colomb as a Shan Chief, Francis Younghusband came as a Shan too (his wife as ‘Cloud with silver lining’).

In 1891, Colomb led a party from Dibrugarh in Assam to the Upper Irrawaday ‘through a country inhabited by friendly tribes’: ‘It is’, glossed

The Times of India, ‘an exploration venture pure and simple’. In the era of the Great Game, there was no such thing. The Indian Army’s Intelligence Branch was clinical and astute in connecting ‘simple’ exploration with imperial strategy, as the physical movements of its agents and their subsequent route reports became critical disciplinary mechanisms on the shelves of government at Simla (

Hevia 2021). Colomb joined the Sikkim-Tibet Demarcation Commission of 1895 as an intelligence officer, and in the same year co-authored a handbook of Yunnan. In 1898 he re-joined the 42nd Gurkhas at Shillong after his years of absence on special duty, and he and his wife Mary were soon performing on the Shillong stage in productions freighted with political and racial meanings about what empire meant to them, shaping as much as projecting imperial ideology.

Basil Copleston Allen arrived in India aged twenty-four in December 1894 and served as Assistant Commissioner at Golaghat before being transferred to Shillong in March 1896 as personal assistant to Chief Commissioner of Assam, Sir William Ward (

Indian Daily News 1896). By May, he had married Ward’s only daughter Mabel at All Saints’ Church (

Queen 1896). The wives of colonial officials were expected to host a range of hospitalities and entertainments, and in turn would be the guests at other events, thus buying in to the informal but nonetheless strict mutuality of station life. Just a month after her wedding, Mabel entered the fray at the fifth gymkhana of the season. While her husband Basil won the ‘Bare-Backed Race’ and was pipped by Major Priestley in the ‘Cheroot-Umbrella’ race (in which riders were required to mount, gallop to the pavilion, dismount, drink a peg, light a cheroot, put up an umbrella, mount again and ride around the course and return with the cheroot alight and the umbrella up), Mrs Allen provided tea for the whole company in ‘her first public appearance as a hostess’, which was judged ‘a pleasing addition’ (

Englishman 1896). In the absence of extended families, colleagues took on the role of surrogate kin. Family connections and their cohort data enable locally contextualised understanding: determining individual health outcomes (such as morbidity and infant mortality) against cohort patterns; the mechanics of preferment, patronage and connection; the micro and macro geographies of colonial mobility; and the intergenerational benefits and deficits of colonial careers. Kiplingesque stereotypes paint the Raj experience in brash primary colours; intimate understandings of the actualities of empire render individuals in more subtle hues, making them more knowable and therefore their personal actions more accountable.

This article has explored some of the methodological possibilities of a critical family history approach to understanding the complex interdependencies of kith, kin and colonial rule at a British hill station in India. The final section of the article reflects on the ways in which critical research into settler-colonial migrations delivers our family histories to the doorstep of the present; its possibilities for informing truth-telling at individual and national levels; and the need for a pedagogy of historical contextualisation and ethical citizenship. Thinking about familial life in British India is inevitably an engagement with the present as much as the past—or at least it should be. Genealogical profiles may be assembled through vital records, but they are also expanded by the memories, archives, and heirlooms of descendant families. The relationship between their postcolonial present and the imperial past of their ancestors has different emotional valence for each individual. Families inherit stories and material objects through bloodlines, but also struggle to understand the relativities of power as the dance of action and inaction, sometimes negotiated, sometimes coerced. Some are inured to the cultural damage of imperialism, either through lack of broader knowledge or their own intransigent ideological positions; some are quick to defend the honour of their forebears; others are induced to hold the past’s complexities in difficult equilibrium, acknowledging that they should not have been in India in the first place, but balancing indubitable harm and misplaced paternalism with good works and moral decisions; others still are roused by conscience to have little emotional attachment to the part their ancestors played in colonial rule.

If selective remembrance (editing out the negatives) is the bane of a traditional family history approach that privileges heroic individuals ‘while rendering invisible the unpalatable actions and consequences of individual actions during colonisation’ (

Campbell and Cuthers 2021, p. 1), we may be wary too about what is occluded or inhibited when isolated stories, in the service of remedial history-making, reducing historical processes to stereotype. Online genealogical platforms are singularly unable to set individual family experience within meaningful historical context. Interest groups like FIBIS (Families in British India Society), established in 1998, provide an important social media space and resource base for family history, but favour empirical data over critical reflection. ‘A fascination with India, its culture and its people’, according to the FIBIS homepage (

FIBIS n.d.), ‘runs deep in our psyche’. For erstwhile members and users like myself, I find the research database (much of it constructed by volunteers) of immeasurable use in my Indian research; I am less comfortable with the nostalgia for Britain’s ‘Jewel in the Crown’ and the fact that encouraging a deeper understanding of imperialism and its effects on colonised and coloniser alike is not one of its six self-avowed aims. An instinct for neutrality is at odds with the life stories of the ‘three million Britons who lived and served in India’; indeed it does them little service by masking the complexity of the Raj and its personal, communal and national consequences, both good and bad.

‘It is a weighty thing’, cautions Victoria Freeman, ‘to sit in judgment upon one’s ancestors … I have tried to see [my ancestors] both as they saw themselves to the best of my ability, and from this present perspective, as an outsider, seeing them as they could not see themselves’ (

Freeman 2000, p. xxiv). Such a process of shared self-assessment rests on our capacity as historians to understand the contested actualities of both ‘presents’—our own, and that of our ancestors. Furthermore, with such information at hand, critical family history may play an important role in atonement. Just as colonialism is a process rather than an event, truth and reconciliation are a measurement of the shockwaves between the past and the present. What role, we might ask, does the emotional resonance of critical family history—in particular, in terms of shame and guilt—play in postcolonial reconciliation processes? (See for example

Allpress et al. 2010).

In the word cloud of critical family history writing to date, negative terminologies abound—

dysfunction,

inequality,

unequal relations,

dispossession,

injustice. Truth-telling and the acknowledgment of individual and collective wrongdoing is an important step along the path of reconciliation. If we slam the door on our difficult ancestors, however, placing them outside of our critical interpretive frameworks or indeed our everyday moral norms (as freak exceptions; or as the bad eggs mitigated by the good), do we run the risk of further ignorance, if not a new puritanism in just ‘feeling-good-about-feeling-bad’? (

Shriver 2022). Whether conceptualised as the ‘inconvenient ancestor’, the ‘reprehensible’, or the ‘repugnant other’, like it or not, our difficult ancestors reside in the house of our inheritance. Lucassen and Smit usefully turn the tables on the common exclusion of ‘invaders’ and repressive elites (from ‘ordinary’ peasants, soldiers or schoolteachers to missionaries, diplomats or corporate expatriates) in understanding the dynamics of organisational migration and hence more complex understandings of why and how people move for work, and the effects of these patternings on themselves, receiving societies and the societies to which they return (

Lucassen and Smit 2015, p. 37). To consider them primarily ‘as the agents of imperialism, capitalism and militarism’, they argue, leaves us with ‘a stubborn and self-limiting heritage’ (

Lucassen and Smit 2015, p. 37); not for a moment suggesting that class and race and power and the hegemonic position of invaders do not matter, but insisting that they have nuanced applications and outcomes which ‘may not always support hegemonic and imperialist agendas’ (

Lucassen and Smit 2015, p. 47). In a slightly different context, legal scholar Kate Gleeson has reflected on our tendency, when dealing with the perpetrators of serious crime, to confine them to the outhouse of the dominant culture. This has the effect of allowing a demonisation of the other, an abdication of core social and political responsibility, and a symbolic self-absolution that exonerates mainstream society (

Gleeson 2004, pp. 184–85). ‘The barbarians, the faces of evil’, she cautions,

‘always have been among us and of us’ (

Gleeson 2004, p. 197).

Historians have long grappled with the task of how to deal ethically with the ‘unsavoury, dangerous, or deliberately deceptive’ political agendas of historical actors (See for example

Blee 1993). Pedagogically, Stéphanie Lévesque elaborated a pathway towards historical empathy in judging the past of predecessors (not necessarily familial) with different moral frameworks. Students, she suggested, might examine ‘their own set of contextualized moralities’ and ‘belief systems’ to be fully prepared for broader historical inquiry. ‘Instead of simply telling students that Hitler was evil,’ she has suggested, ‘educators should lead them to discover why he is considered evil, on what grounds and from what re-enactable evidence’ (

Lévesque 2008, pp. 167–69). Critical family history, I argue, may profitably be drawn into this preparatory framework for ethical understanding, historical contextualisation and moral judgement.

A new generation of scholars is grappling with this in different ways in the light of generational shifts in thinking about the meanings and representations of the colonial past in the present and the emotional calculus of shameful personal legacies (See for example

Cox 2021). The work of

R. Shaw (

2021a,

2021b) being a case in point, it has often taken outsiders to history as a discipline to write

across disciplines. There is also a developing literature—mainly within social and political psychology rather than history—on the relationship between ‘the sins of the fathers’ and the possible or perceived moral obligations of descendants, whether in the context of European colonisation in India, Indonesia, Africa, Australia and the Americas, or intergenerational guilt over America’s atomic bombing of Japan in World War 2 (

Leach et al. 2013;

Leone and Sarrica 2014;

Goto et al. 2015;

Martinovic et al. 2021). Again, critical family history might provide an important building block for collective reckoning in what to date has been a general focus on in-group, intergroup or outgroup dynamics when exploring ideas of guilt, shame and self-critical sentiment about the colonial excesses or genocidal sins of ancestors.

Notions of collective guilt, like it or not, play a role in post-conflict and postcolonial reconciliation and nation-building: Allpress et al. have found ‘that people can experience emotions for wrongs committed by a group to which they belong—even before they were born and against people no longer alive—and that these emotions can have important effects on contemporary intergroup relations’ (

Allpress et al. 2010); Sven

Zebel et al. (

2007, p. 83) note a correlation between high family involvement in colonial pasts with negative or positive views of an individual’s social self; in the context of the ‘haunting legacies’ of the Nazi ancestral past, Gabriele Schwab explores the transgenerational transmission of trauma in descendants of perpetrators (

Schwab 2010); and

Mukashema and Mullet (

2015, p. 95) believe that while acknowledging the wrongs of the past is a special social duty of the offspring of perpetrators, to unhitch any sense of

personal guilt from past wrongdoing is much more likely to lead to collaborative reparation.

The metaphor of the nation-as-family (founding fathers, motherland, homeland security) is a persistent cultural framework and a dangerous ethno-nationalist trope when it serves as a security that is intolerant of the other (

Burke 2002;

Ely-Harper 2014;

Lakoff 2016;

Chang et al. 2020;

Martin 2020). The buried secrets of families, counsels Ann McGrath, are also the secrets of the nation (

McGrath 2016). As a national pastime, the pursuit of critical family history may play a transformative role for the individual researcher as ‘public pedagogy’, encouraging historical imagination as well as the development of historical consciousness (

E. Shaw 2021). It also offers tantalising opportunities for historical pedagogy at a secondary or indeed tertiary level. Maya Jasanoff’s Harvard course on ‘Ancestry: Where do we come from and why do we care?’ draws together insights from biology, anthropology, genealogy, history, law and memory studies to contextualise the power of genealogy in terms of understanding kinship, nation, race, ethnicity and eugenics.

6 Perhaps considered as a core foundation of any history curriculum, it has broad applicability as undergirding approaches to national or global history and citizenship—to acknowledge and understand origins; locate actors within structures; assess individual life stories against collective patterns; connect families to historical processes, as agents as well as victims—so that ‘Who do you think you are’? becomes ‘Who do we think we might become?’

It is perhaps ironic that in a historical moment of iconoclasm towards individual representatives of colonialism and slavery through the tearing down of statues or the renaming of places, that critical family history raises its hand to insist on the importance of sighting, knowing and remembering the individual in the shifting territory of the past. Tracing difficult ancestors across the globe can shed new light on the ways in which their migratory experiences effected longer term cultural or political transformation, for good as well as for bad, and as repatriates (

Lucassen 2021) as well expatriates. A genealogy is not a resolute map of the world as it was; it is a singular pathway through it that leads us to the threshold of the present and may assist in accommodating the ethical challenges and truth-telling processes of postcolonial domiciles.