Mixedness and Intersectionality: The Use of Relief Maps to Understand the Experiences of Multiracial Women of African Descent in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

(…) reflection on one’s own life is what makes it possible to politicize the experience of oppression and to name concrete forms of violence, discrimination and inequality, but also of agency, which were not even named (p. 137) (…) [B]y analyzing the concrete situated experience, one tries to understand how the different systems of inequality function, how they relate to each other and what role emotions and places play in their reproduction.(pp. 173–74)

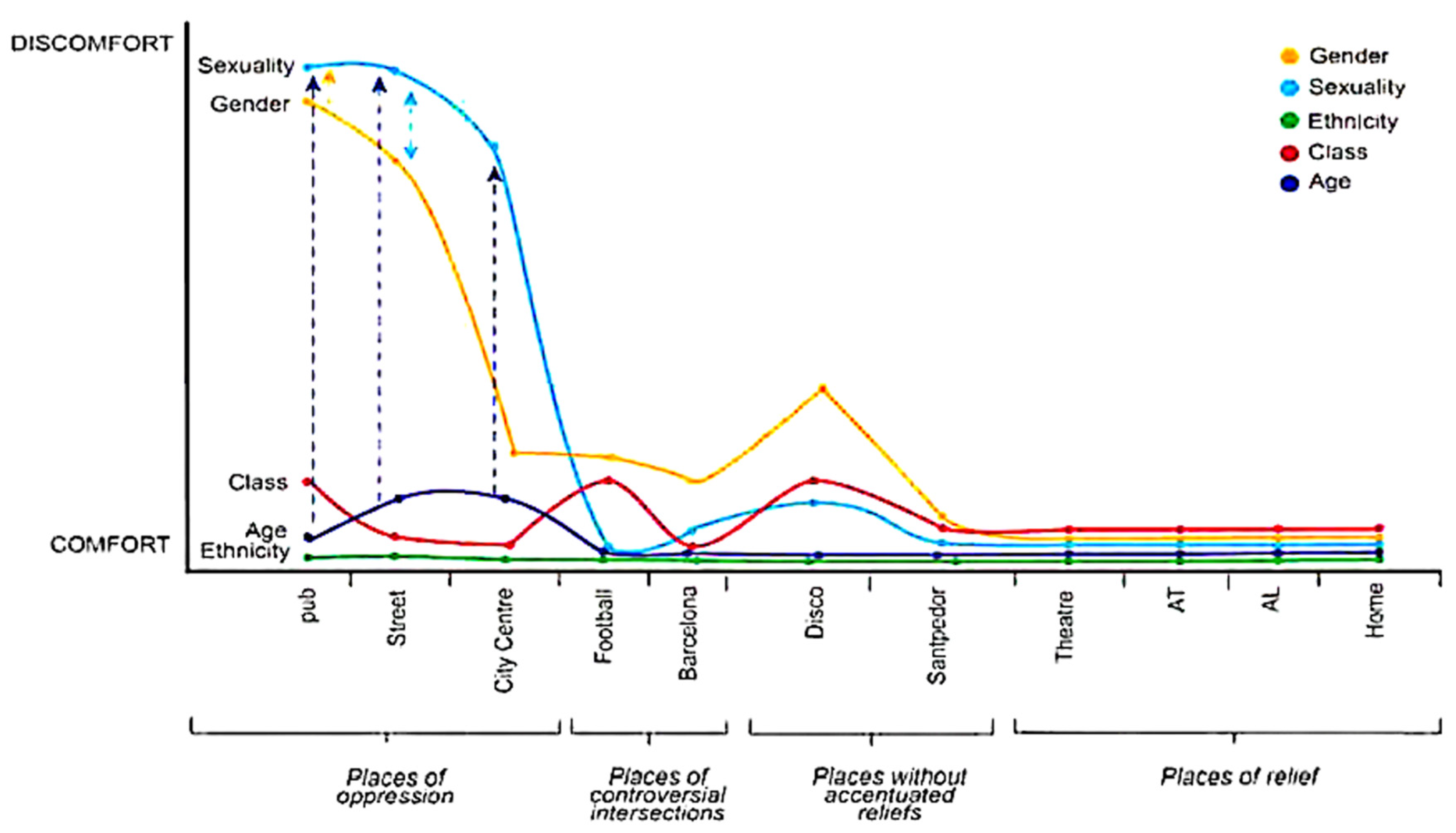

Relief Maps propose an approach to intersectionality that is not based on social categories, but on power structures (p. 195) (…) By making structures visible, and not identities, and by adding the dynamism of place, [Relief Maps] focus on the effects produced by positions and not on the positions themselves. In other words, they focus on the systematic dynamics of the (re)production of inequality, rather than on questions of identity.(p. 196)

3. Results

Discomfort, Well-Being, and Places: An Intersectional Reading

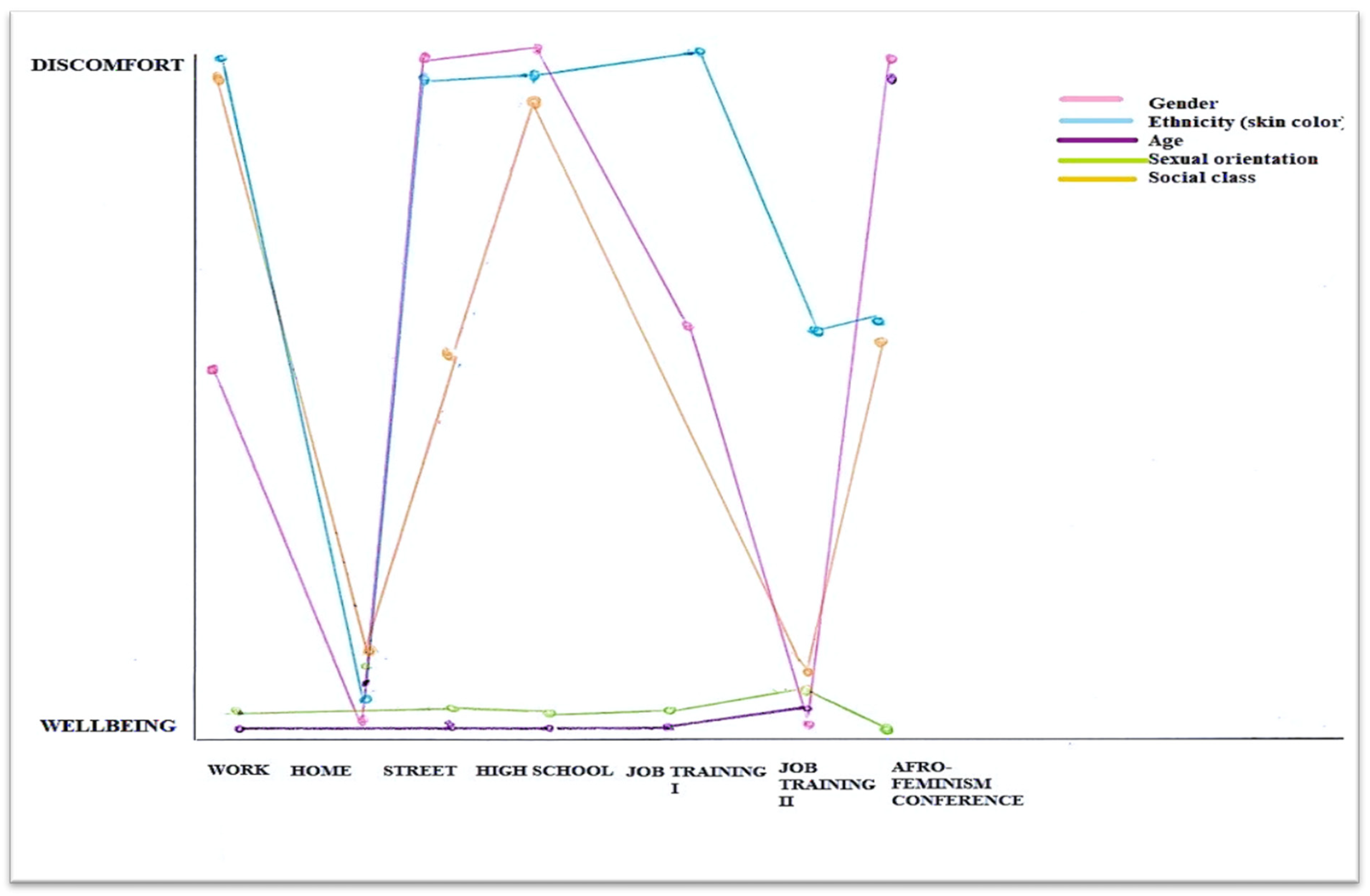

[The fact] that your people also treat you badly (…) It makes you feel insecure. (…) He stopped me—and I am used to being stopped because of [my dog]: “Oh, she’s lovely! Can I pet her?” And I said, “OK, you can pet her.” That’s what people do, isn’t it? [People just] touch her head and that’s that. At that moment, he petted her head, but he touched me too—that is, he touched my breast. I haven’t worn a bra for a long time and I felt very uncomfortable, and I pulled back, and so did he, and I pulled back farther and said, “Well, I’m going. Bye.” And I turned to go and saw that he [still] had his hand on my chest. And I said, “I’m going! I’ll pass!” (…) [And he said,] “Oh, but what’s your name?” And I said, “Let me get by, please.” [And he said,] “Oh, I want a girlfriend like you.” And I said, “I already have a boyfriend. Let me pass. I won’t tell you again.”Sara, 22 years old, Brazilian father, Colombian mother

A joke is a joke and even I sometimes find them funny, but…sometimes they did go too far. You’d say, “I just don’t feel like it; it’s not necessary right now.” But there were many jokes of this kind (…) When I was younger, I even thought, “I wish I’d been born white; everything would be much easier” (…) It affects me less [now], yes [in high school]. I’ve reached a point where I feel good about who I am and this part of me [my skin color]. And when I’m fed up, I just don’t listen to them [the jokes]. I reach a point where I don’t care and I block it out (…) They throw as many [jokes] at me as they want and I laugh because I don’t want to have problems (…) I reach a point at which I feel fed up with it and then I triple block it.Judith, 16 years old, Senegalese father, Spanish mother

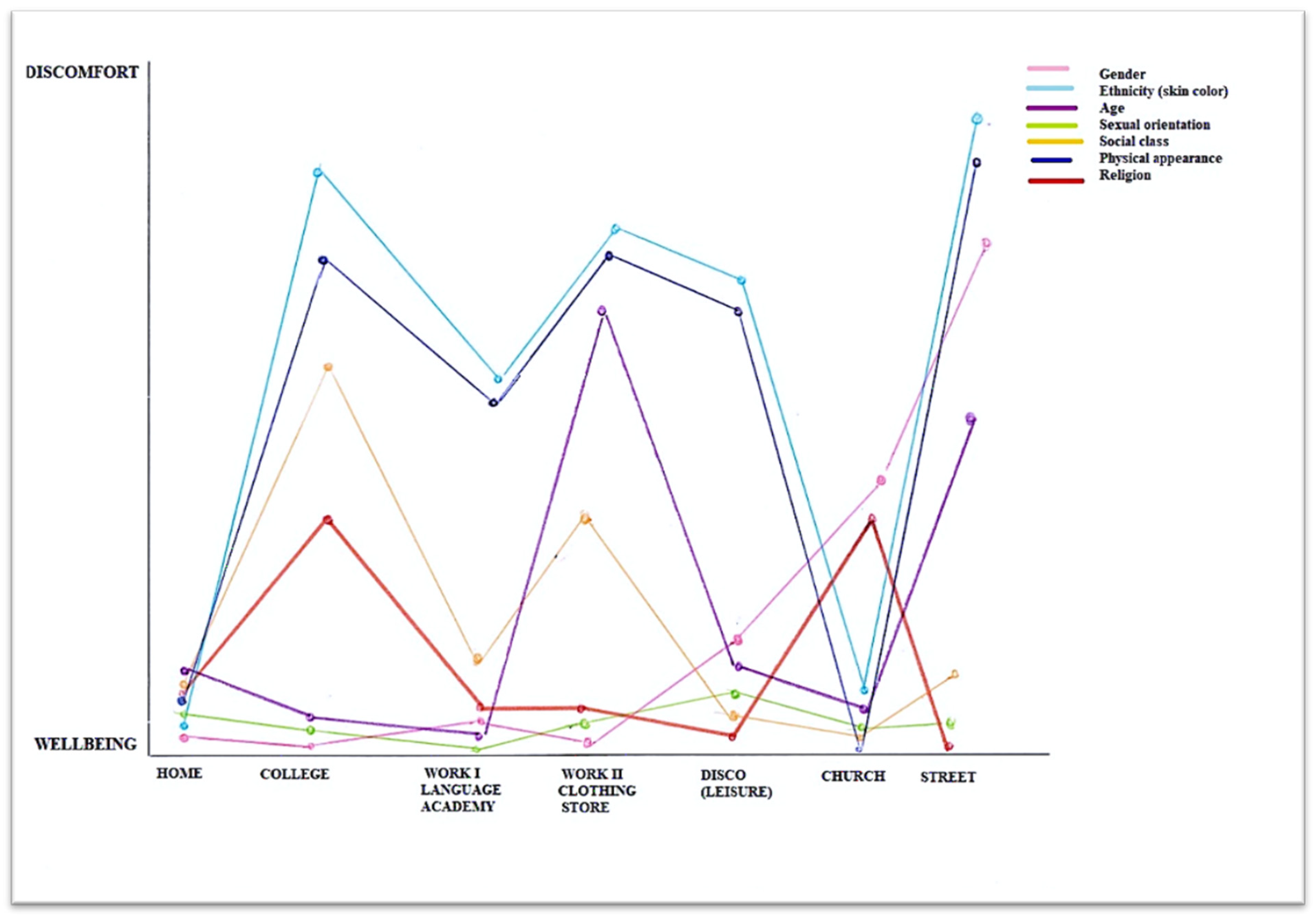

Because of the color of my skin and my physical appearance, I don’t feel identified with anyone. The fact that I am the only racialized girl makes me feel different (…) These are my feelings, but sometimes [this perception] makes me feel uneasy. Sometimes I think, “Maybe if I were white, this wouldn’t happen to me.”Anna, 19 years old, Spanish father, Dominican mother

The color of my skin (…) I was really in over my head and it was one of the times when… I have also put it in my reflections [she refers to another activity called Intimate Writing]—that there was a time when I quite detested my skin color.Maria, 25 years old, Congolese father, Spanish mother

I’ve always been the chubbiest person (…) [I’ve received] the typical comments of “You shouldn’t eat so much” [or] “These clothes, don’t they make your thighs look more pronounced?” (…) In this society in which we live, in the end, women have to be 36-23-36 and it’s quite shameful (…) I didn’t decide to be this way.

So I’ve heard comments like, “You’ve put on a bit of weight.” They say that with all the love in the world, but they don’t have to (…) My family and my friends [in the church] are the people who can destabilize me the most psychologically, I mean, totally, totally, totally.

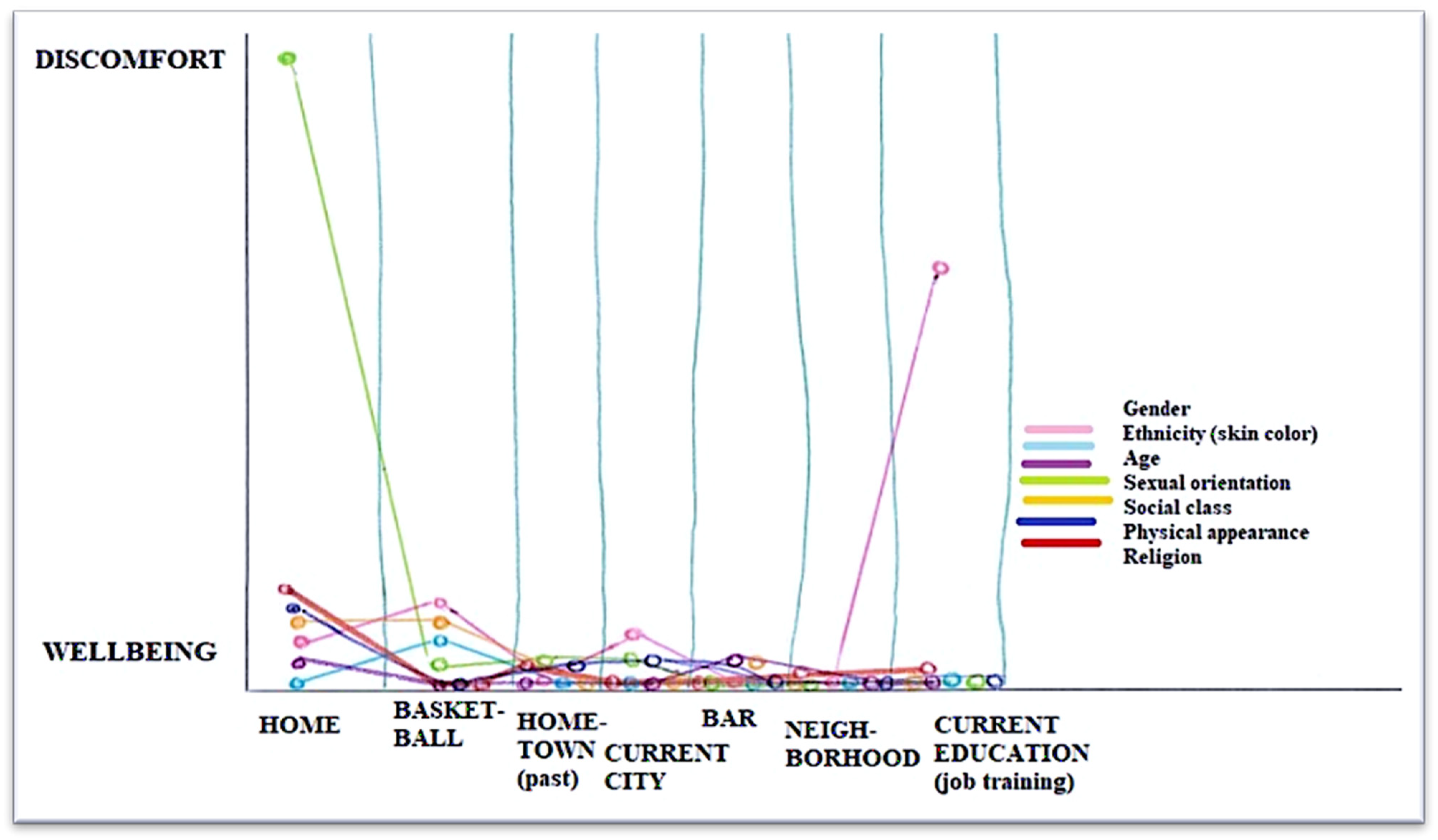

“You are too young, shut up” (…) “Girls your age, you shouldn’t dress like that” (…) They know that if they say something to me, it gets into my head and if I go out, I will be uncomfortable all day long and I won’t wear it [the outfit or item of clothing] anymore (…) My mother has a major complex about her legs…and [that] I’ll have the same legs as her (…) Her complex has been passed on to me [by telling me,] “Don’t get fat; be careful about this (…) Later on, you’ll feel bad.”

It’s because of my mother. She doesn’t accept my sexual orientation, but she respects it. But her way of respecting it is not to talk about it. So, it makes me uncomfortable and there are comments I have to keep quiet. [Regarding my mother’s awareness of my sexual orientation] I think it was three weeks, a month, that she didn’t look at me or talk to me (…) From that moment on, I have never brought up the issue with my mother again. Sometimes, I’ve thought about telling her that I have a girlfriend, but then I am scared shitless, and I think, “Better not; don’t tell her anything,” because I don’t want her to stop talking to me again.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Afro-descendant” is the term that is commonly used in Spain (including by activist groups and civil society organizations) to refer to people of African descent, so we have used it in this article when specifically discussing the Spanish context. |

| 2 | The larger study was titled “Social Relations and Identity Processes of Children of Mixed Unions: Mixedness—Between Inclusion and Social Constraints (MIXED_YOUTH)” and was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, National Program for Research Aimed at the Challenges of Society (Grant No. CSO2015-63962-R), 2016–2020; PI: Dan Rodríguez-García. The doctoral thesis was funded by the Agency for Management of University and Research Grants of the Catalan Government (Grant No. 2018FI_B_00605). |

| 3 | For this study, a total of 152 in-depth interviews were conducted with Spanish-born youth from very diverse ancestries, representing 51 different nationalities. To know more about the scope, methodology, and results of this study, see Rodríguez-García (2022) and Rodríguez-García et al. (2018, 2021b). |

| 4 | “Geographies of intersectionality” are a sort of theoretical corpus within spatial studies that promote and claim the need to incorporate the intersectional and critical perspective, establishing bridges between intersectional studies, feminist geographies, and critical geographies (Rodó-de-Zárate 2021, p. 65). |

| 5 | As we argued at the beginning of this article, our approach to the analysis of racialization is based on the social significance of certain perceived “visible” elements that are associated with the social construct of “race.” In this sense, we join the line of critical thought that argues for the importance of including “race” as a category of analysis on the basis of its social function despite its biological fiction (Haider 2020, p. 23; Hughey 2017, p. 27). For further discussion on this matter, see also Rodríguez-García (2022). |

| 6 | It should be noted, as Rodó-de-Zárate (2021) explains, that the identification of separate axes, dimensions, and variables is an abstraction of reality, as, in fact, they all occur simultaneously and are interrelated. |

| 7 | We have used pseudonyms to refer to the research participants in order to ensure their anonymity. |

| 8 | Mari Luz Esteban (2004a) defines this objective and approach very well when referring to the itinerarios corporales (itineraries of the body) that she describes in her book Antropología del Cuerpo: Género, Itinerarios Corporales, Identidad y Cambio, “itineraries” that in our case would be equivalent to the Relief Map of each participant. She defends her intention to show them from both “the singularity and the complexity of each itinerary, configuring them as what they are: open, porous, contradictory and unfinished itineraries” (p. 13). |

| 9 | As explained in the Methodology section, we insist that a purely visual reading of the Relief Map, without the complementary information that interpretation and first-person accounts allow, is both biased and incomplete. We, therefore, advise caution before making hasty assumptions. We try to provide here as much information as possible to allow the reader to make a more complete reading of each Relief Map. However, because of space constraints, it will not be possible to qualify the multiple connections and readings permitted by this tool. |

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Suki. 2003. Mixed-Race, Post-Race: Gender, New Ethnicities and Cultural Practices. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anthias, Floya. 2007. Gender, Ethnicity and Class: Reflecting on Intersectionality and Translocational Belonging. The Psychology of Women Review 9: 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anthias, Floya. 2020. Translocational Belongings: Intersectional Dilemmas and Social Inequalities. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Cardona, Ana María, and Sara Victoria Alvarado Salgado. 2015. Investigación narrativa: Apuesta metodológica para la construcción social de conocimientos científicos. Revista CES Psicología 8: 171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bastia, Tanja. 2014. Intersectionality, Migration and Development. Progress in Development Studies 14: 237–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, Mercedes. 2012. ¿Autobiografía o autoetnografía? Desacatos 38: 169–78. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers, and Frederick Cooper. 2000. Beyond “Identity”. Theory and Society 29: 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsma, David. 2006. Mixed Messages: Multiracial Identities in the “Color-Blind” Era. Boulder: Lynne Reinner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, Caitlin. 2009. The Personal Is Political: Developing New Subjectivities through Participatory Action Research. Gender, Place & Culture 4: 267–92. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, Karis. 2021. Mapping Black Mixed-Race Birmingham: Place, Locality and Identity. Sociological Review 69: 937–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chito Childs, Erica. 2006. Black and White: Family Opposition to Becoming Multiracial. In Mixed Messages: Multiracial Identities in the “Color-Blind” Era. Edited by David Brunsma. Boulder: Lynne Reinner Press, pp. 233–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chito Childs, Erica. 2014. A Global Look at Mixing: Problems, Pitfalls and Possibilities. Journal of Intercultural Studies 35: 677–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Sumi, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Leslie Williams McCall. 2013. Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38: 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2015. Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology 41: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2017. Intersectionality and Epistemic Injustice. In The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 115–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo Parriego, Rosalía, ed. 2007. Memoria Colonial e Inmigración: La Negritud en la España Posfranquista. Barcelona: Bellaterra. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 140: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, Ochy. 2014. Construyendo metodologías feministas desde el feminismo decolonial. In Otras Formas de (Re)Conocer: Flexiones, Herramientas y Aplicaciones desde la Investigación Feminista. Edited by Irantzu Mendia Azkue, Marta Luxán, Matxalen Legarreta, Gloria Guzmán, Iker Zirion and Jokin Azpiazu Carballo. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco, pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Angela. 1981. Women, Race and Class. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux, Kay. 2018. Ethnic/Racial Identity: Fuzzy Categories and Shifting Positions. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 677: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. 2001. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Lanham: Rowman Altamira, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2015. Autoetnografía: Un panorama. Astrolabio 14: 249–73. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, Mari Luz. 2004a. Antropología del Cuerpo: Género, Itinerarios Corporales, Identidad y Cambio. Barcelona: Bellaterra. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, Mari Luz. 2004b. Antropología encarnada. Antropología desde una misma. Papeles del CEIC, International Journal on Collective Identity Research 12: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1952a. The Fact of Blackness. In Postcolonial Studies: An Anthology. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1952b. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraroti, Franco. 1981. Vite di Periferia. Milan: Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, René. 2015. The Resurgence of Race in Spain: Perceptions of Discrimination among Immigrants. Social Forces 94: 237–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, Mónica Montaño. 2011. Diáspora africana; retos frente a la “etnocolonización”. In II Congreso Internacional “Africa-Occidente”: Corresponsabilidad en el Desarrollo. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva, pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, Mónica Montaño. 2016. Negro-Africanos en la Provincia de Huelva: Entre la Integración y el Racismo. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Huelva, Huelva, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, Mónica Montaño. 2018. Lo negro-africano y afrodescendientes: Procesos identitarios por asignación o autoreconocimiento. Revista de Pensamiento Estratégico y Seguridad CISDE 3: 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Giliberti, Luca. 2013. La Condición Inmigrante y la Negritud en la Experiencia Escolar de la Juventud Dominicana: Estigmas y Formas de Agencia. Una Etnografía Transnacional entre la Periferia de Barcelona y Santo Domingo. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Lleida, Lleida, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, Gabrielle. 2019. Embodied Resistance: Multiracial Identity, Gender, and the Body. Social Sciences 8: 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2009. Apuntes hacia una metodología fanoniana para la decolonización de las ciencias sociales. In Piel Negra, Máscaras Blancas. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, pp. 261–84. [Google Scholar]

- Habimana-Jordana, Teresa. 2021. Una aproximació metodològica a l’estudi de la mixticitat des de la interseccionalitat i l’auto-antropologia. Quaderns de l’ICA 37: 137–58. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, Asad. 2020. Identidades Mal Entendidas. Raza y Clase en el Retorno del Supremacismo Blanco. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2007. When Multiplication Doesn’t Equal Quick Addition. Perspectives on Politics 5: 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, Donna. 1991. Ciencia, Cyborgs y Mujeres: La Reinvención de la Naturaleza. València: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Sandra, ed. 2004. The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holman Jones, Stacy. 2005. Autoethnography: Making the Personal Political. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, pp. 763–91. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 1992. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End. [Google Scholar]

- Hughey, Matthew W. 2017. Race and Racism: Perspectives from Bahá’í Theology and Critical Sociology. Journal of Bahá’í Studies 27: 7–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabardo, Mercedes. 1998. La inmigración femenina africana y la construcción social de la africanidad. Ofrim Suplementos 3: 175–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jabardo, Mercedes. 2002. Las múltiples formas de africanidad. Las mujeres africanas se reinventan a sí mismas en el Maresme. Paper presented at IX Congreso de Antropología del Estado Español, Barcelona, Spain, September 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jabardo, Mercedes. 2005. Migraciones y género. Cuando el continente africano se hace pequeño. Revista Española de Desarrollo y Cooperación 16: 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jorba, Marta, and Maria Rodó-de-Zárate. 2019. Beyond Mutual Constitution: The Properties Framework for Intersectionality Studies. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 45: 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, Nikki. 2010. “If You’re Half Black, You’re Just Black”: Reflected Appraisals and the Persistence of the One-Drop Rule. Sociological Quarterly 51: 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugones, Maria. 2008. Colonialidad y género. Tabula Rasa 9: 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, Helma, Ann Phoenix, and Nira Yuval-Davis, eds. 1995. Crossfires: Nationalism, Racism and Gender in Europe. London and East Haven: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Guzmán, Antar, and Marisela Montenegro. 2014. La producción de narrativas como herramienta de investigación y acción sobre el dispositivo de sexo/género: Construyendo nuevos relatos. Quaderns de Psicologia 16: 111–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- May, Vivian M. 2015. Pursuing Intersectionality: Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mbembe, Achille. 2016. Crítica de la Razón Negra: Ensayo sobre el Racismo Contemporáneo. Barcelona: Ned Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Charles Wright. 1970. La Imaginación Sociológica. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Henrietta. 1988. Feminism and Anthropology. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal, Kevin L., Kristin C. Davidoff, and Victoria McKenzie. 2015. A Qualitative Approach to Intersectional Microaggressions: Understanding Influences of Race, Ethnicity, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion. Qualitative Psychology 2: 147–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netto, Vinicius M. 2012. A reconquista da cidade: Polis e esfera pública. Cadernos do Proarq, Rio de Janeiro 19: 265–88. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Anibal. 2005. Colonialidade do poder, eurocentrismo e América Latina. In A Colonialidade do Saber: Eurocentrismo e Ciências Sociais. Perspectivas Latino Americanas. Edited by Edgardo Lander. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- Reece, Robert L. 2019. Coloring Weight Stigma: On Race, Colorism, Weight Stigma, and the Failure of Additive Intersectionality. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 5: 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodó-de-Zárate, Maria. 2014. Geografies de la interseccionalitat: L’accés de la joventut a l’espai públic de Manresa. Doctoral Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Rodó-de-Zárate, Maria. 2016. Geografies de la interseccionalitat: Llocs, emocions i desigualtats. Treballs de la Societat Catalana de Geografia 82: 141–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rodó-de-Zárate, Maria. 2021. Interseccionalitat. Desigualtats, Llocs i Emocions. Manresa: Tigre de Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan. 2015. Introduction: Intermarriage and Integration Revisited: International Experiences and Cross-disciplinary Approaches. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 662: 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan. 2021. Forbidden Love: Controlling Partnerships Across Ethnoracial Boundaries. In International Handbook of Love: Transcultural and Transdisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Claude-Hélène Mayer and Elisabeth Vanderheiden. Cham: Springer, pp. 923–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan. 2022. The Persistence of Racial Constructs in Spain: Bringing Race and Colorblindness into the Debate on Interculturalism. Social Sciences 11: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan, and Cristina Rodríguez-Reche. 2022. Daughters of Maghrebian Muslim and Native Non-Muslim Couples in Spain: Identity Choices and Constraints. Social Compass 69: 423–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan, Miguel Solana-Solana, Anna Ortiz-Guitart, and Joanna L. Freedman. 2018. Linguistic Cultural Capital among Descendants of Mixed Couples in Catalonia, Spain: Realities and Inequalities. Journal of Intercultural Studies 39: 429–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan, Teresa Habimana-Jordana, and Cristina Rodríguez-Reche. 2021a. “Tú, como eres negra, harás de lobo”. El debate pendiente sobre la cuestión de la raza en España. Perifèria: Revista de Recerca i Formació en Antropologia 26: 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan, Miguel Solana, Anna Ortiz, and Beatriz Ballestín. 2021b. Blurring of Colour Lines? Ethnoracially Mixed Youth in Spain Navigating Identity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47: 838–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan, Verónica de Miguel Luken, and Miguel Solana. 2021c. Las uniones mixtas y sus descendientes en España: Evolución y consideraciones sobre la mixticidad. In Anuario CIDOB de la Inmigración 2020. Edited by Joaquín Arango, Blanca Garcés, Ramón Mahía and David Moya. Barcelona: CIDOB, pp. 168–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rosaldo, Michelle Zimbalist. 1974. Woman, Culture, and Society: A Theoretical Overview. In Woman, Culture, and Society. Edited by Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo and Louise Lamphere. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sipi, Remei. 1997. Las Mujeres Africanas. Incansables Creadoras de Estrategias para la Vida. L’Hospitalet: Mey. [Google Scholar]

- Sipi, Remei. 2000. Las asociaciones de mujeres, ¿agentes de integración social? Papers: Revista de Sociología 60: 355–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Miri. 2017. Ethnic Options of Mixed Race Young People in Britain. In Identities and Subjectivities. Edited by Nancy Worth, Claire Dwyer and Tracey Skelton. Singapore: Springer, pp. 123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Varro, Gabrielle. 2003. Sociologie de la Mixité. De la Mixité Amoureuse aux Mixités Sociales et Culturelles. Paris: Belin. [Google Scholar]

- Verloo, Mieke. 2006. Multiple Inequalities, Intersectionality and the European Union. European Journal of Women’s Studies 13: 211–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2007. Super-Diversity and Its Implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30: 1024–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoya, Mara V. 2016. La interseccionalidad: Una aproximación situada a la dominación. Debate Feminista 52: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2006. Intersectionality and Feminist Politics. European Journal of Women’s Studies 13: 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambelli, Elena. 2021. Interracial Couples and the Phenomenology of Race, Place, and Space in Contemporary England. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habimana-Jordana, T.; Rodríguez-García, D. Mixedness and Intersectionality: The Use of Relief Maps to Understand the Experiences of Multiracial Women of African Descent in Spain. Genealogy 2023, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010006

Habimana-Jordana T, Rodríguez-García D. Mixedness and Intersectionality: The Use of Relief Maps to Understand the Experiences of Multiracial Women of African Descent in Spain. Genealogy. 2023; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabimana-Jordana, Teresa, and Dan Rodríguez-García. 2023. "Mixedness and Intersectionality: The Use of Relief Maps to Understand the Experiences of Multiracial Women of African Descent in Spain" Genealogy 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010006

APA StyleHabimana-Jordana, T., & Rodríguez-García, D. (2023). Mixedness and Intersectionality: The Use of Relief Maps to Understand the Experiences of Multiracial Women of African Descent in Spain. Genealogy, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010006