Java Community Philosophy: More Children, Many Fortunes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context

3. Method

4. Results

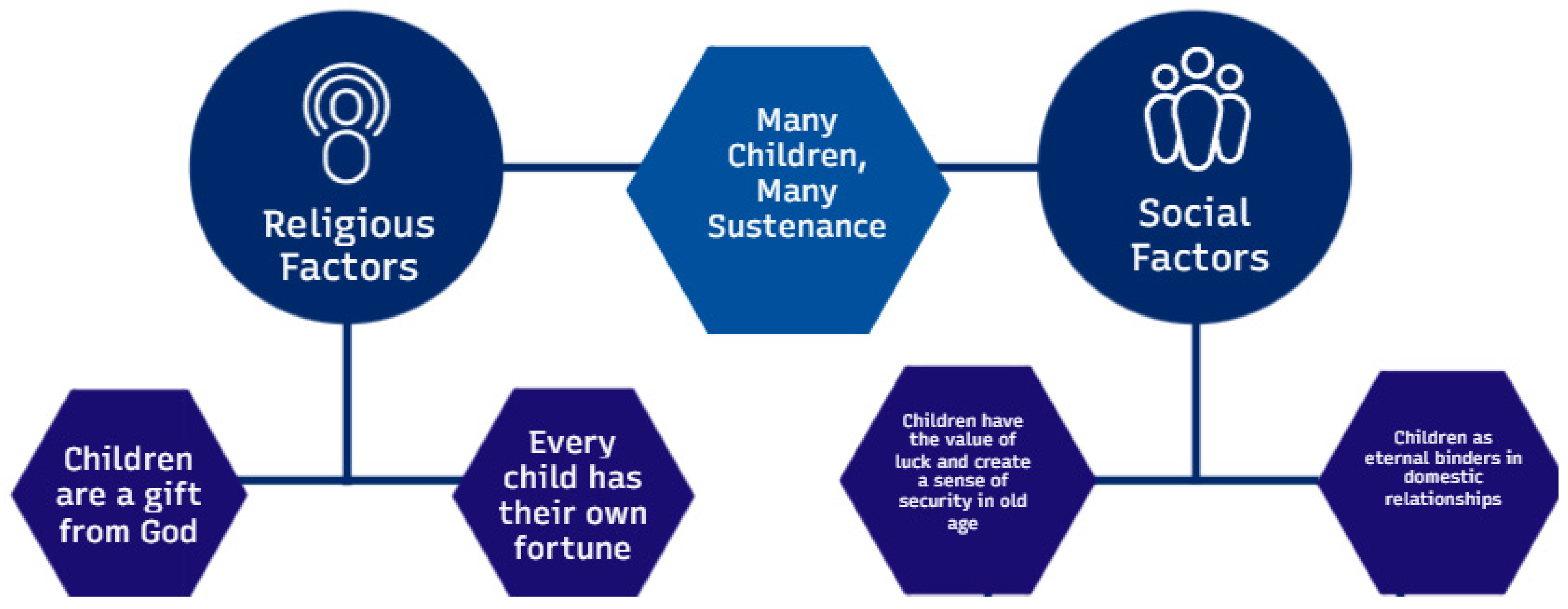

4.1. Children Are a Gift from God

Since the beginning of our marriage, we have agreed that we want to live well and build a household according to our religious values. This includes the number of children in the family. We do not use contraceptives because we believe it is God’s right to determine the number of children in the family. Since we do not want to violate God’s decree, we do not follow the family planning program. My wife and I started a small business, and Alhamdulillah (praise to God), our company continues to grow with time. God also trusted us to have five children, three boys and two girls. Alhamdulillah, our lives are fulfilled even though we have many children. Yes, that’s it, fortune has already been arranged, so I did not allow my wife to take family planning because it violated God’s decree. Children are a blessing. When they get to be born, then let them be born. When we do not have a child, we cannot do anything. I do not want to refuse God’s fortune to our family.(P1, lines 4–12)

Yes, I have eight children, two girls and six boys. Alhamdulillah, healthy and shalih shalihah (“shalih and shalihah” is Islamic term for “benevolent”). Since I was young, I have never joined any family planning program. I will accept it with pleasure no matter how many children God gives. For me, limiting the number of children is going against the deed God has set. In our belief, preventing a child’s birthright is a despicable act.(P8, lines 4–8)

I firmly believe that children by themselves are God’s fortune for humans. Allah says, “Do not kill your children for fear of poverty; we will provide fortune for you and them.” (Surah Al An’am [6]: 151). Furthermore, when the children are pious and grow up worshipping Allah, the gifts to their parents increase, making life more blessed. The parents’ hard work in educating their children to become pious servants of God is the reason for the more blessings. Since parents inform their children, they have the fear of Allah. Furthermore, Allah says about the fruit of piety, “Whoever fears Allah, He will provide for him a way out and give him sustenance from a direction he did not expect.”.(Surat Ath Thalaq [65]: 2–3)

4.2. Every Child Has Their Fortune

All children born are guaranteed fortune by God. As a parent, I keep trying and working to meet all the needs of the children. We feel that having many children is not a problem. The more children, the more fortune because it makes me work diligently to meet the children’s needs.(P3, lines 67–71)

Many children have much luck, which is a belief in my family and me. Fortune has already been arranged. The fortune could be abundant wealth, health, and happiness that comes with every child. Allah SWT guarantees and provides it.(P8, lines 63–66)

Yes, I have five children in school. Some are in elementary and middle school, and some are in college—the youngest is in 1st grade. I have many children because they are a gift from God. Suppose I had never thought that a child was a burden. The child is a gift from God. God promises that every creature would get a fortune. Therefore, I am sure fortune has been arranged. I believe that each child brings their own luck and fortunes. Why should it be limited?(P13, lines 71–76)

The birth of a child in a family brings fortune. Something determined by Allah is the best, whether there are many children or no children. I am very grateful because we are blessed with three cute children. The analogy is straightforward. The Qur’an states that even reptiles have their fortunes guaranteed by Allah. Humans also have guaranteed fortunes.(P14, lines 63–67)

4.3. Children as Family’s Success Symbol

We view our children as a gift from God, which is very valuable. Therefore, we educate and take care of them with love. I have two sons and three daughters, all in school. When they grow up, they can get a good job and become priyayi(P10, lines 78–80)

PARTICIPANT (P5): I have 5 children, all girls. I still intend to get pregnant again because I hope to have a boy.

INTERVIEWER: Why do you need a son, Ma’am? Aren’t girls and boys the same?

PARTICIPANT (P5): Yes. People say it is the same for boys or girls, but we long for a boy in our family to be complete. I have a pregnancy program to get a boy. Moreover, my husband wants a son. He said that when he was old, the son could help replace his father’s role in society.(P5, lines 92–93)

4.4. Children as Eternal Binders in Domestic Relationships

About seven years ago, I almost divorced my husband because I still had no children after so many years of marriage. We often fought and blamed each other, it got worse when there was a third-party intervention. However, I finally got pregnant with my first child. A year later, I got pregnant again, and now I have three children, and my family is improving. When my husband and I have a problem, we immediately forgive each other. I feel sorry for the children when their parents fight.(P7, lines 82–87)

My wife and I almost divorced because we had no children after ten years of marriage. Finally, our extended family allowed us to adopt a child to keep our household harmonious. Ultimately, we can live together and be happy, though the child is not our blood. We love our little daughter with all our hearts. Five years after adopting a child, my wife became pregnant with twins and another baby two years later. When my wife becomes pregnant again in the future, we would never refuse it because children are the source of happiness in our family. We love all our children(P9, lines 90–96)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Safii, “Konsep Kesempurnaan Hidup Orang Jawa: Sebuah Tinjauan Filologi Terhadap Serat Madurasa.” |

| 2 | World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. |

References

- Agustina, Rina, Teguh Dartanto, Ratna Sitompul, Kun A. Susiloretni, Endang L. Achadi, Akmal Taher, F. Wirawan, Saleha Sungkar, Pratiwi Sudarmono, Anuraj H. Shankar, and et al. 2019. Universal health coverage in Indonesia: Concept, progress, and challenges. The Lancet 393: 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, Chittaranjan. 2021. The Inconvenient Truth About Convenience and Purposive Samples. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 43: 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryanti, Nina Yudha. 2017. The strategy of Ethnic Identity Negotiations of Javanese Migrants Adolescents in Family Interaction. Komunitas: International Journal of Indonesian Society and Culture 9: 237–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnani, Devi Pratiwy, Safitri Hariani, Sri Wulan, and Amrin A. Siregar. 2019. Cultural Aspects in Andrea Hirata’s Novel Sirkus Pohon. KnE Social Sciences, 125–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Howard, and Geer Blanche. 2020. Participant Observation: The Analysis of Qualitative Field Data. In Field Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boog, Katie, and Michelle Cooper. 2021. Long-acting reversible contraception. In Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS Indonesia. 2021. Catalog: 1101001. In Statistik Indonesia 2020. 1101001; p. 790. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2020/04/29/e9011b3155d45d70823c141f/statistik-indonesia-2020.html (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Brevers, Damien, Chris Baeken, Pierre Maurage, Guillaume Sescousse, Claus Vögele, and Joël Billieux. 2021. Brain mechanisms underlying prospective thinking of sustainable behaviours. Nature Sustainability 4: 433–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Steve, Melanie Greenwood, Sarah Prior, Toniele Shearer, Kerrie Walkem, Sarah Young, Danielle Bywaters, and Kim Walker. 2020. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing 25: 652–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, Denok Maya. 2016. ‘Banyak Anak Banyak Rejeki’ vs. ‘Dua Anak Cukup’ Via Program KB Di Kota Batam [“Many Children, Many Fortunes” vs. ‘Two Children Are Enough’ Via the Family Planning Program in Batam City]. Journal of Law and Policy Transformation 1: 94–122. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Joshua A. Wilt, Nick Stauner, William A. Schutt, Kenneth I. Pargament, Frank D. Fincham, and Ross W. May. 2021. Supernatural Operating Rules: How People Envision and Experience God, the Devil, Ghosts/Spirits, Fate/Destiny, Karma, and Luck. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffara, Ghefra Rizkan, Dayu Ariesta Kirana Sari, and Nanda Saputra. 2021. Javanese Cultural Heritage Building (Case Study: Joglo House). Lakhomi Journal Scientific Journal of Culture 2: 148–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentles, Stephen J., Cathy Charles, Jenny Ploeg, and K. Ann McKibbon. 2015. Sampling in qualitative research: Insights from an overview of the methods literature. Qualitative Report 20: 1772–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardavella, Georgia, Ane Aamli Gagnat, Daniela Xhamalaj, and Neil Saad. 2016. How to prepare for an interview. Breathe 12: e86–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Harrison, Anthony Kwame. 2020. Ethnography. In The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, Enung. 2019. Pengalaman Remaja Tentang Pola Asuh Keluarga di Kota Yogyakarta. Yogyakarta: Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanah, Enung, M. Ikhwan Al Badar, and M. Ikhsan Al Ghazy. 2022. Factors That Drive the Choice of Schools for Children in Middle-Class Muslim Families in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. A New Beginning 27: 1393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, Enung, Zamroni Zamroni, Achmad Dardiri, and Supardi Supardi. 2019. Indonesian adolescents’ experience of parenting processes that positively impacted youth identity. Qualitative Report 24: 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, Agus, Mohammad Arief, and Wening Patmi Rahayu. 2018. Dimensions of the Javanese culture and the role of Parents in instilling values in creative industry entrepreneurship. International Journal of Engineering and Technology 7: 182–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, Nazanin M. 2010. Developing theory with the grounded-theory approach and thematic analysis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 23: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ikhsan, M. T. Hartono, and Sandi Fauzi Giwangsa. 2019. The Importance of Multicultural Education in Indonesia. Journal of Teaching and Learning in Elementary Education (JTLEE) 2: 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzah, Latifatul. 2017. Munculnya Filosofi “Banyak Anak Banyak Rizki” Pada Masyarakat Jawa Masa Cultuurstelsel. Kumbakonam: SASTRA. [Google Scholar]

- Kasnadi, Kasnadi, and Sutejo Sutejo. 2018. Islamic religious values within Javanese traditional idioms as the Javanese life guidance. El Harakah (Terakreditasi) 20: 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koentjaraningrat. 1962. The Javanese Family: A Study of Kinship and Socialization. Hildred Geertz. American Anthropologist 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laily, Ainun Nurul, Sunlip Wibisono, and Fivien Muslihatiningsih. 2012. Analisis Fertilitas di Kecamatan Bangsalsari Kabupaten Jember. Artikel Ilmiah Mahasiswa. [Google Scholar]

- Memmi, Daniel. 2019. The relevance for the science of Western and Eastern cultures. AI and Society 34: 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulya, N., E. Nurlaelah, and S. Prabawanto. 2018. Students’ statistical literacy in junior high school. International Conference on Mathematics and Science Education of Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia 3: 710–14. [Google Scholar]

- Muntamah, Ana Latifatul, Dian Latifiani, and Ridwan Arifin. 2019. Pernikahan dini di indonesia: Faktor dan peran pemerintah (perspektif penegakan dan perlindungan hukum bagi anak). Widya Yuridika 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Amrin, Reza, Haidar Muttaqy Zaen, Muhammad Prayoga Dwi Nugraha, Prihariyanda Putra, Rifqian Izza Zaini, and Yehuda Rainata Sangkay. 2021. Permasalahan Pertanahan pada Daerah Berkepadatan Penduduk Rendah [Land Problems in Low Population Density Areas]. Widya Bhumi 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, Trena M., Elizabeth M. Pope, Nicholas Woolf, and Christina Silver. 2019. It will be very helpful once I understand ATLAS.ti”: Teaching ATLAS.ti using the Five-Level QDA method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 22: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presiden Indonesia. 2009. Undang-undang Nomor 52 Tahun 2009. Available online: www.legalitas.org (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Ramesh, Balasubramaniam, Lan Cao, Jongwoo Kim, Kannan Mohan, and Tabitha L. James. 2017. Conflicts and complements between eastern cultures and agile methods: An empirical investigation. European Journal of Information Systems 26: 206–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reling, Timothy T., Michael S. Barton, Sarah Becker, and Matthew A. Valasik. 2018. Rape Myths and Hookup Culture: An Exploratory Study of U.S. College Students’ Perceptions. Sex Roles 78: 501–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiq, Rafli Muhammad, and Nunung Nurwati. 2021. Pengaruh kepadatan penduduk terhadap tindakan kriminal. Jurnal Kolaborasi Resolusi Konflik 3: 161–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Adika May, Rina Lestari, Desri Yani, and Rosmita Rosmita. 2019. Aplikasi pengenalan kebudayaan jawa berbasis desktop. Jurnal Teknik Informatika 12: 121–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, Suryani, and Suraili Suraili. 2021. Analisis Semiotika Iklan Layanan Keluarga Berencana (Kb) Versi Pernikahan Dini. Journal of Islamic Communication and Counseling 1: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sutikno, Achmad Nur. 2020. Bonus demografi di indonesia. Visioner: Jurnal Pemerintahan Daerah Di Indonesia 12: 421–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synthesa, Putricia. 2021. Spatial Analysis of The Effect of Women’s Autonomy on Fertility in Indonesia. Jurnal Berkala Kesehatan 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Deloris S. 2018. Awareness of God, Intrinsic Religious Motivation, Calling, and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: A Quantitative Evaluation of Entrepreneurial Intention and Alertness to Entrepreneurial Opportunity. Ph.D. thesis, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Trisnani, Dwi. 2020. Ketiadaan anak laki-laki: Akankah menjadi faktor penghalang pemakaian kontrasepsi? Jurnal Kesehatan Kusuma Husada, 113–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardani, Thesya Josevin, and Arnellis Arnellis. 2019. Faktor-faktor yang Mempengaruhi Ketidakmerataan Jumlah Penduduk di Indonesia Menggunakan Analisis Faktor. UNPjoMath 2: 4. [Google Scholar]

- William, William. 2020. Angka kelahiran di Indonesia masih tinggi, mengapa mayoritas laki-laki ogah ikut KB. San Francisco: The Conversation. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, Veronika. 2014. World society and globalization. Journal for Multicultural Education 8: 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometer. 2022. 278,917,146. pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/indonesia-population/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Wuri Arenggoasih, Mukti Al. 2021. Ethics and Human Dignity as Communication of Javanese Family that Interfaith Religious Life. Psychology and Education Journal 58: 5417–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Muhadi. 2005. Menuju Keluarga Sakinah (Membentuk Keluarga Sakinah Berdasarkan Perspektif Islam. Psikologika: Jurnal Pemikiran Dan Penelitian Psikologi 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hua, Fuxiao Li, and Katherine J. Reynolds. 2022. Creativity at work: Exploring role identity, organizational climate and creative team mindset. Current Psychology 41: 3993–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasanah, E. Java Community Philosophy: More Children, Many Fortunes. Genealogy 2023, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010003

Hasanah E. Java Community Philosophy: More Children, Many Fortunes. Genealogy. 2023; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasanah, Enung. 2023. "Java Community Philosophy: More Children, Many Fortunes" Genealogy 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010003

APA StyleHasanah, E. (2023). Java Community Philosophy: More Children, Many Fortunes. Genealogy, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010003