Abstract

For centuries, Asians living in the U.S. have had to negotiate between the narratives that dominant society has imposed upon them and their understanding of what it means to be Asian and Asian American. When combined with the hierarchies of racial categories, the narratives underlying monoracialism are inherently limiting, obscuring their nuanced experiences, and stripping them of their ability to express the personal constructions of their identity The purpose of this qualitative case study was to elevate the voices of Asians and Asian Americans, their process of “inventing” their identity, and how their conceptualizations begin to deconstruct and challenge monoracialism. I argue that Asians and Asian Americans engage in a process where the interpretation and revision of meaning that emerges during interactions with others can illuminate the role of master narratives and how they negotiate between these structural factors and their ideas of what it means to be Asian or Asian American. The findings suggest a negotiation between master narratives at the macro-, meso-, and micro-societal levels that help them understand what it means to be Asian and Asian American.

1. Introduction

Who we are is bound by the stories about us and those we tell ourselves. Monoracialism seeks to essentialize the story of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. to confine them to hegemonic ideals of appearance, character, and behavior. As () reminds us, “race operates as a verb before it assumes significance as a noun” (p. 104). Monoracialism, therefore, is a method where racial categories are combined with and reinforced by narratives constructed at the macro level to dictate Asian and Asian Americans’ othered position in society. () referred to these as master narratives, which are stories created and shared within a given culture, that contribute to the overall structure of that society. According to the authors, master narratives “provide guidance for how to be a ‘good’ member of a culture” (p. 320). Monoracialism within U.S. society is a function of how the dominant social group has racial hierarchies. Monoracialism and master narratives go hand in hand, where racialization must contend with the U.S.’s answer to who belongs. Dominant society has created these good member stories and stories around racial groups to maintain that hierarchy. For those who do not fall within its immutable ascriptions, monoracialism is, thus, an extension of an already oppressive system that further marginalizes individuals and different Asian groups ().

The over 40 national and ethnic groups included under the banner of the Asian racial category () further complicate the deconstruction of monoracialism. Each group celebrates traditions and values that may contrast with one another and those espoused by the American culture, further complicating how members of these communities conceptualize their identities. Commenting on the complex reality of identifying as Asian American, () noted, “Asian Americans are made not born…our true place of origin nowhere to be found on a map” (pp. 306–7). He claimed that they instead “invent” themselves. Like Wu, () argued that early immigrants first included in the Asian racial category are distinct from Asians of today, having stated, “The emergence of an Asian racial category is related to but distinct from the persons we might describe as Asian Americans who populate or inhabit the racial category. Asian Americans remain to be invented” (p. 956). I argue that Asian and Asian American inventions may hold the key to deconstructing monoracialism and that master narratives influence this invention and how they think about their ethnic and racial identities ().

This paper aimed to elevate the voices of Asians and Asian Americans, their process of “inventing” their identity, and how their conceptualizations begin to deconstruct and challenge monoracialism. Drawing from a synthesis of master narrative (), symbolic interactionism (), and Asian critical race theory (), I argue that Asians and Asian Americans engage in a process where the interpretation and revision of meaning that emerges during interactions with others can illuminate the role of master narratives and how they negotiate between these structural factors and their ideas of what it means to be Asian or Asian American. The following research questions guided the study:

- What master narratives do Asians and Asian Americans refer to when describing their ethnic and racial identities?

- How have these master narratives shaped the way they conceptualize their ethnic and racial identities?

Considering the power of master narratives, I argue that deconstruction will include the challenging, reinforcing, and maintenance of master narratives as participants interpret meanings attached to them to define their identity.

2. Voices at the Center

I break briefly with convention to introduce my participants here. I include a brief discussion of my participants earlier in this paper to show how their self-reported identities informed how I wrote this paper and chose to use the terms Asian and Asian American out of respect for their positions.1 Eric, Lewis, Lourdes, and Nittha’s descriptions of their identities speak to the problematic nature of racial categories and how they miss the nuances between ethnic groups. Their identities speak to the challenges in navigating monoracialism and the cultural pressures they must navigate when considering their Asian identities within U.S. American society. My participants’ identification as Asian or Asian American was significant in understanding how they deconstruct monoracialism.

During my interview with Eric, he referred to himself as Vietnamese and not Vietnamese American, stating that identifying as such meant he was part of the “in-group” of American society and its cultures and values. On the other hand, Lewis compartmentalized his identity, describing the process as one where he wears different masks; one Filipino and one American. Nittha and Lourdes, like Lewis, immigrated to the U.S. with their parents prior to attending the university but referred to themselves as Thai American and Filipino American, respectively, during the interviews. While Lourdes did not speak about her international status at the university, Nittha and Lewis mentioned that they were considered international students at SVSU.

Positionality

A paper discussing the deconstruction of monoracialism could only be complete with a statement of positionality. I identify as Filipino American. Often, stating my identity results in questioning how much I can claim of either. I would like to know if I am Filipino enough to make such a declaration knowing that I subscribe to the many values I have learned growing up in the U.S. To me, American is everything Filipino is not, yet I cannot explain what that means. I also know that my parents and the dominant society around me would not see me as wholly belonging to either category. Each would view my bi-cultural, non-white identity as “not quite there”. Therefore, I am on a quest to understand what it means to be Filipino (or Asian) and American. I study identity and Asians in America with the hope that one day through this process, I can state clearly and declaratively who I am.

3. Theoretical Framework

I framed the study using a synthesis of master narrative (M.N.) (), symbolic interactionism (S.I.) (), and Asian critical race theory (AsianCrit) (). M.N. serves as the central framework from which I consider the influence of monoracialism in Asian’s and Asian Americans’ understanding of their racial identity. S.I. and AsianCrit then supplement M.N. to account for how participants negotiate with master narratives to deconstruct monoracialism and the different ways Asians have been positioned in U.S. society.

() proposed a five-principal model to identify master narratives, including their utility, ubiquity, invisibility, compulsory nature, and rigidity. Master narratives are the stories created at the cultural level, which I argue occur at both the macro, meso, and micro levels, that help to structure a society. They provide the life “paths” individuals must follow to align with the expectations imposed on them by society. Master narratives surrounding women, as described by McLean and Syed, dictate that they must grow up to become mothers and choose family over career. According to the authors, women who choose not to have children deviate from or resist this master narrative. Identifying master narratives within a culture or society provides insight into how individuals align with these stories, thus internalizing these narratives or resisting them to create alternative narratives, as seen with women who choose not to have children to form personal narratives. () emphasized the power of master narratives and pointed to how even while resisting them and creating an alternative narrative, individuals recognize and even validate master narratives. To resist is to acknowledge that something exists from which to deviate. An essential contribution of their work involves the agency of individuals to create personal and alternative narratives. They argued that the power of master narratives inherently limits individual agency in creating their own narratives. Specifically, they state, “The stifling nature of master narratives, how strongly they can shape personal stories, and how much this shaping occurs without awareness, is central to our model, and it applies to those who both resist and internalize master narratives” (p. 336). This idea is particularly integral to the study of deconstructing monoracialism. The narratives woven around racial groups dictate society’s expectations and force racialized groups to navigate and negotiate the boundaries of existence imposed upon them.

(), highly influenced by the work of George Herbert Mead, maintained that individuals act not merely in response to a situation but engage in communication with the self to inform action during interactions with others. Blumer’s work enhances () model by offering a perspective from which to view an individual’s process of creating personal and alternative narratives. Through his SI framework, he argued that individuals interpret the meaning behind actions, or as Blumer refers to them, gestures that then inform action. He noted that these gestures are related to objects that hold meaning for individuals and must be seen as social creations. Race itself, as a socially constructed object, holds meanings. () pointed out that society is fundamentally made up of people engaging in action, which occurs in response to one another. Blumer’s argument, thus, indicates that individuals actively negotiate the meanings others imbue in those objects that are visible () to them with their meanings of those same objects. During this process, deconstructed meanings toward those objects are either reinforced or reconstructed by the individual as those meanings change through the interaction. Through McLean and Syed’s M.N. framework, they argue that individuals’ personal narratives are composed of master and alternative narratives. Master narratives that are part of a person’s identity (personal narrative) have been internalized, where communication with the self reinforces how they are “following” society’s rule for being a “good member” (). Alternative narratives occur when self-communication reveals they either differ from or actively resist master narratives.

The framework from which I examine the negotiation of Asians and Asian Americans would not be complete without Chang’s framework of Asian critical race theory. A key aspect of () M.N. model is the limitations of personal agency in an individual’s identity construction. AsianCrit offers a foundation to understand how our narratives, and by extension, our identities, have been constructed at the macro level. Chang argued that the population experiences discrimination not as part of the larger grouping of people of color but specifically as Asians and Asian Americans. He stated, “To deny difference may erase Asian American identities and may be inadequate to address fully the needs of Asian Americans” (p. 45). As () noted, “the members of an ethnic group may be seen as a different kind of object by members of other groups” (p. 11). Blumer’s argument is of particular importance to note as it can shape the ways Asians and Asian Americans interpret interactions with other people of color, which further inform the meanings they designate to their race and cultural identity.

The synthesis of the three theoretical frameworks is as follows, M.N. () argued that cultures create the foundations from which individuals understand how to be good members of society. Individuals may internalize these narratives, leaving them invisible as they follow the paths their societies have set out for them. However, when master narratives become visible, individuals may find they are passively living an alternative narrative or may actively engage in the resistance of these narratives. McLean and Syed pointed out that their framework did not directly address the process by which individuals negotiate these narratives. () S.I. framework offered a perspective from which to understand how individuals interpret, create, and recreate meanings related to objects of import during interactions. Master narratives can represent the objects that have become visible to the individual during these interactions. For Asians and Asian Americans, there are master narratives inextricably linked to their racial identity. According to AsianCrit (), the ways Asians and Asian Americans have been oppressed in society are directly related to the specific narratives associated with the population, namely the model minority and perpetual foreigner. While these are the two most discussed stereotypes associated with Asians and Asian Americans, there are nuances within the cultures included in the monolith racial category that the M.N. framework can help uncover.

4. Literature Review

4.1. Race and Asian Americans

Race has served to create boundaries around the bodies of different groups, and justification for assigning specific characteristics, values, and behaviors to people of color, and the Asian and Asian American identity must take into consideration how they have been positioned and have navigated both racial and cultural dimensions of identity in Western society. As discussed above, Asians and Asian Americans are racialized differently from other groups in the forms of the model minority and perpetual foreigner, which simultaneously feed into the yellow peril. () emphasized how race as a “highly salient organizing social category” (p. 11) is used for both identity and identification. She suggested that identification organizes individuals into demographic groups, while identity is “the meaning individuals and groups ascribe to membership in racial categories” (). Racial identity is marked by distinct boundaries constructed by the current social, cultural, and political climate (). According to (), racial identity is formed “in constant flux in response to shifting demographic, social, and geopolitical dynamics” (p. 3).

The construction of the Asian race and the macro-societal narratives, or stereotypes, associated with the Asian body present an illustration of the processes through which Asians and Asian Americans have been racialized throughout history (), with these representations shifting in salience as they are influenced by social forces (). () referred to this process as the invention of the Asian race. He stated, “Understanding that race is what race does is vital to understanding the construction of the Asian racial category within the United States” (p. 952), and thus, critical to understanding the importance of counternarratives in challenging the oppression of Asian Americans. Unfortunately, the stigmatization of Asians and Asian Americans is again rising. New reports of anti-Asian violence depict the community as a foreign threat due to their perceived role in the recent pandemic. At times a model minority, while at others a yellow peril, they have been forced to reconcile the contradictions imposed upon them by Western society through hegemonic ideals and the pervasiveness of monoracialism, which often places them against both White Americans and other people of color. Kim’s theory of racial triangulation specifically addressed this positioning. She argued that positioning Asians and Asian Americans in U.S. society serves as a tool to maintain the racial hierarchy. By simultaneously highlighting Asians’ foreignness and their inability to assimilate to U.S. cultural values and their successes relative to Black Americans, the dominant society can reinforce racist practices. This position effectively removes Asians and Asian Americans from examinations of racism, thus perpetuating monoracial ideologies through our absence. To counter these narratives, we must continue to not only push for the inclusion of Asian and Asian American voices in scholarship on race but to allow for the elevation of our nuanced experiences as racialized people.

4.2. Ethnicity, Race, and the Process of Racialization

Throughout this discussion, I have described how race and ethnicity are viewed through a specific time’s social, cultural, and political climate. In other words, ethnicity and race are rooted in the social realm and cannot be viewed without first looking at the other. Recognizing the social construction of ethnicity and race is particularly important when considering critical race theory and the dynamic relationship between race, power, and privilege (). A review of Asian and Asian American history in the U.S. reveals how their ethnic and racial identity, those physical and geographical markers that distinguished the population from those of European descent, and the sociopolitical climate surrounding their arrival and residency in the U.S. resulted in sanctioned exclusionary laws barring citizenship and restricting immigration (; ; ; ). Over a hundred years later, Asians and Asian Americans, as a racialized monolith, experienced another dramatic change in how dominant society began to view their perceived success at achieving the “American dream” (). For example, the notion of the model minority is consistently applied to Asian and Asian American and can impact their success in postsecondary education. Scholars such as () and () note the undue pressure placed on Asian and Asian Americans to perform academically, a form of stereotype threat. Although typically associated with negative stereotypes, “Such findings show that not only do negative stereotypes threaten one’s ability and psychological well-being, but seemingly positive stereotypes also can be burdening to members of the stereotyped group” (). Based on the discussion above, the instability of race and the fluidity of ethnicity lend themselves to explorations within specific sociohistorical, sociopolitical, and cultural contexts, especially when viewed as a dimension of identity, which, as I discuss in the following section, is also a function of the social.

4.3. The Complexity of the Asian and Asian American Racial Body and Ethnic Heart

The Asian and Asian American identity is complicated by considering not only the phenotypical markers othering them from the majority but also those ethnic traditions distinguishing one Asian group from another. Research on Asian and Asian American identity has often looked at racial and ethnic identity as part of the overall identity but has yet to consider their complex interplay. () explored how second-generation Asian and Asian Americans interacted with one another and pointed to internalized racism among their participants. In their findings concerning how participants distinguished themselves from one another, either labeling someone as “fresh-off-the-boat” or FOB or as whitewashed, they pointed to how ethnic identity or the expression of cultural traditions could result in participants’ efforts to move away from either extreme identity to achieve balance. The use of racial and ethnic identity interchangeably highlights the ways Asian and Asian American identity is both rooted in phenotype and culture.

(), on the other hand, explicitly noted how the pan-Asian term had transformed to address the ethnic diversity within the larger racial identifier. He pointed to how the Asian American identity has transformed from a “political-racial identifier” (p. 542) to one that considers the increasing diversification of the Asian label. Park’s participants employed the term Asian American in diverse ways, which emphasized how the appropriation of a number of meanings toward the term can result in it becoming less salient for one individual, whereas it may be more to another. He noted how race and ethnicity are caught in an intricate relationship he called “racialized multiculturalism (p. 557). Park defined racialized multiculturalism as how race and the legitimation of cultural diversity interact to create multiple meanings behind the categories of Asian and Asian American. According to (), considering the aspect of Asian and Asian American ethnic identity “does not diminish the importance of race” (p. 3). They emphasized how clinicians counseling postsecondary education Asian and Asian Americans should facilitate explorations of participants’ racial and ethnic identities to understand their well-being better. Their work spoke specifically to the complexities of identifying as an Asian and Asian American when looking at how racial and ethnic identity impact experiences. These authors’ work supports how the Asian and Asian American identity label has shifted over time to include how the population has evolved to view the term through their own experiences, thus constructing their identities around personal definitions of Asian and Asian American. These constructions must be considered from the ethno-racial perspective as one cannot be viewed without the other, especially when exploring Asian and Asian American identity. The work conducted by (); (); and (), among others, helped to situate the ways Asian and Asian Americans could view and describe their construction and understanding of Asian and Asian American as an ethno-racial identity.

4.4. Creating Ethnic and Racial Borders

The identity of people of color is often viewed from an ethnic or racial lens. Models such as () and () make mention of ethnicity, or in the case of Helms and Cook, the negotiation of cultural values and norms, in participants’ progression toward an ethnic or racial identity, but do not explicitly refer to the interplay from the ethno-racial perspective. Social scientists have reached a consensus that race is not scientific evidence of cognitive or physical ability but remains a visible stigma used to stratify and organize our social worlds (; ; ; ; ; ; ). () stated, “From its inception, race was a folk idea, a culturally invented conception about human differences” (p. 22). Ethnicity, too, has served to create boundaries from which people from different countries of origin engage in negotiation between adopting the dominant society’s values and practices and maintaining a connection to their own. () pointed out the role of ethnicity and race in creating borders around communities of descent. He stated, “Americans have mixed in certain ways and not others, and they have talked about it in certain ways and not others” (para. 4). According to (), “Race is a concept that signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests by referring to different types of human bodies” (p. 147). They warn that to view race through the lens of ethnicity is to “downplay questions of descent, kinship, and ancestry” (p. 22). I maintain, however, that the Asian or Asian American identity cannot be viewed without taking into consideration how Asian or Asian Americans have navigated both racial and cultural dimensions of identity in Western society.

However, theories regarding the processes related to racialization, which inform racial identity, are continuously debated and developed by scholars (; ; ; ; ). In addition, to consider the identity of people of color through either an ethnic or racial lens is to look at only one part of their journey to understand their sense of self. Viewing identity through the perspective of its impact on people of color throughout American history then calls for considering both race and ethnicity. This offers an opportunity to view race and ethnic identity through multiple perspectives rather than limiting the discussion to one lens, which in turn restricts possibilities for analyzing data. This study aims to explore Asian and Asian American narratives beyond those constructed at the macro-societal level. It explores narratives created through ethnic traditions and interactions and those formed at the familial level, shaping how individuals understand their Asian and Asian American identities.

5. Methods

This paper presents a secondary analysis and utilizes a case study inquiry strategy, one of the five strategies included in a qualitative research design. A case study was adopted to understand how Asian and Asian Americans negotiate between master narratives constructed at the macro level and their understanding of their racial identity. A hallmark of qualitative research design is that it provides an opportunity to capture the unique and personal perspectives of Asian Americans’ experiences negotiating between their conceptualization of identity and society’s ideals while navigating a majority–minority environment. Furthermore, there are specific characteristics associated with qualitative research, which encourage the creation of space suited for shining a light on the participants’ voices, which includes: locating the study in the social context in which the research problem occurs (), recognizing the importance of participant voice and meanings ascribed to social phenomena; and acknowledging the active role of the researcher (; ). Additionally, qualitative research is primarily inductive () and, as such, provides opportunities to explore areas in which little research exists (; ; ).

5.1. Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

5.1.1. Participants

I asked participants to provide their ethnic identities on the demographic survey collected before the interviews. Table 1 represents their responses. Four participants included American as part of their information on the demographic questionnaire. Apart from Eric and Lewis, all other participants referred to themselves as Asian Americans during the interview. Participants were 18 years and older and identified as either Asian American or Asian who was been born in the U.S. (Eric) immigrated prior to applying, enrolling, and attending the university (Lewis, Lourdes, and Nittha). Renee’s experience as an adoptee was singular to the study. She was adopted from abroad and raised by white parents in the northern part of the United States. There were seventeen females, six males, and one who chose not to respond to the gender question on the demographic survey. To preserve this participant’s choice not to identify, I chose a gender-neutral name and used the pronouns: they, their, and them. Of the 24 participants, 14 were graduate students, and ten were undergraduates. Participants’ self-reported average age range was 21–25 years old. Participants identified from a range of Asian backgrounds, including six biracial students and one identifying as Japanese Korean. One participant, Robert, listed Chinese on the demographic questionnaire but later identified as Chinese Filipino during the interview.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and Interview Information.

Biracial or multiethnic participants and those identifying as only one Asian ethnic group offered complementing perspectives on the Asian racial identity. Those identifying with only one Asian ethnic group pointed out how Western identity constructs were imposed upon their racialized bodies. Participants talked of ways they have had to navigate spaces in which they are hyper-visible and at times in which they felt unsafe. Biracial students discussed their identity as opportunities to choose when and how to use their Asian and/or White or Black identity, as with Amelia.

As mentioned above, Lewis, Lourdes, and Nittha had immigrated to the U.S. before attending high school, allowing them to immerse themselves in the national and local environment. Their experiences provided a rubric from which to explore race and cultural identity where they had been exposed to both their respective Asian ethnic backgrounds and life in the U.S. Students who grew up outside of the Southwest or moved away for some time, to include study abroad, entered the space with different perspectives as well. A.K. (raised in the Midwest), Amelia (study abroad), Anne (raised in a predominantly Korean community), Elizabeth (raised on the East Coast), Erica (moved away temporarily), Harry Potter (attended undergraduate on the West Coast, raised in the local community), Hermione (raised on the West Coast), Hee Sun (raised on the East Coast), Jess (raised on the West Coast), Kathy (raised on the West Coast), Leah (raised on the West Coast, moved to the surrounding community during elementary school), Lourdes (raised in the Southeast U.S. and moved to a city near SVSU during adolescence), Mia (raised on the West Coast), Noelle (raised on the West Coast, moved to the local community for work), Participant 19 (attended undergraduate at historically white institution), and Yoon Hee (attended an undergraduate institution on the East Coast but returned to complete their undergraduate degree at SVSU) represented how living away, even for a brief time, changed their perspectives regarding their Asian and Asian American identities. These experiences shared by participants served to build upon the complexities of being Asian and Asian American in the U.S. Participants’ narratives were directly employed in various iterations of coding, including their own words and interpretations of how they conceptualized their ethnic and racial identities. The experiences of participants built upon one another and provided support for the final analysis. A breakdown of participants’ gender, age, class status, and race can be found in Table 1.

5.1.2. Recruitment

I recruited participants during the spring semester of 2017 between March and May. Recruitment involved sending brief advertisement requests to student digital newsletter offices and the universities’ media outlets. Sun Valley State University (SVSU) displayed my announcements on the campus’s T.V. screens allowing for greater participation from students. Requests sent to similar offices at the University of Texas River Path (UTRP) went unanswered. However, I was able to make a brief announcement at the beginning of one course offered through the Asian Studies minor at UTRP. A sample email of the Invitation to Participate can be found in supplementary documents (see the Supplementary Materials “Invitation to Participate: Email Communication”). In addition, I sent messages to various social media pages of different student organizations. Finally, at the end of each interview, I asked participants if they could recommend potential participants for the study, a method known as snowball sampling. Once contact had been initiated, I provided participants with a link to a brief demographic survey and an electronic version of the informed consent form. I scheduled interviews upon receipt of each demographic questionnaire completed. Recruitment ended when contact from potential volunteers ceased.

5.1.3. Data Collection

As mentioned, the current paper presents a secondary analysis of data collected for a study on the experiences of Asian and Asian American students attending a Hispanic-serving institution. This original study began with an unstructured interview protocol adapted from (). I asked participants to “Tell me about your experiences as an Asian American student attending SVSU/UTRP. I’d like to hear your story in your own words and, should the need arise, I will ask additional questions for clarification or elaboration.” During data collection, two other questions emerged:

- What does being Asian American mean to you?

- How would you describe how Asian Americans are perceived on campus?

Twenty-four unstructured interviews with undergraduate and graduate Asian and Asian American students were conducted to gather data on their experiences while attending a Hispanic-serving institution. Interviews were conducted in locations specified by the participant but restricted from occurring in private domiciles, such as dorms or homes, and private offices to ensure safety and potential issues concerning Title IX guidelines. Plans were made to schedule conference rooms in respective college departments or enclosed study areas at the institutions’ library and tutoring centers. Participants also chose to meet via Skype or Facetime or be interviewed over the phone. The participant determined interview lengths, which varied from 30 min to 2 h. Participants were not compensated for their time.

5.2. Data Analysis

This paper presents a secondary analysis of data collected for a study on the experiences of Asian and Asian American students attending a Hispanic-serving institution (HSI) in the southwest region of the United States. I originally coded data by hand and followed () grounded theory coding methods. I used in vivo codes during the initial coding session, which () argued “serve as symbolic markers of participants’ speech and meanings” (p. 55). Codes about cultural traditions, such as language, the exotification of Asian women, the feelings expressed by participants during interactions with others, their thoughts on the Asian American identity, and perceived intelligence, to name a few, were included during this initial phase of coding. I then began to organize data into broader themes, categorizing in vivo codes according to their shared topic. For example, coding all data describing the participants’ experience speaking an Asian language simply as “Access to ethnic language skills”. Interactions between participants and others were coded as “Relationships”, and descriptions of experiences outside the higher education setting were coded as “Childhood/adolescence”, “Local community”, or “Study abroad”. Codes involving “being smart” were coded for “Model Minority”.

During this secondary analysis, I returned to my original codes and viewed them through the lenses of my three theoretical frameworks. I used Dedoose to organize my original data and codes. Coding involved an iterative process where larger categories, such as those listed above, were broken down and reformed using the major concepts of each theoretical framework, such as:

- Master narrative (): master narrative, alternative narrative, internalization, differing, and resistance;

- Symbolic interactionism (): family, peers, international Asian students, elementary school, middle school/junior high, high school, college/university;

- AsianCrit (): model minority, perpetual foreigner, denial of difference, affirmation of difference, and liberation from difference.

I returned to the data, repeatedly reviewing codes, and testing them against the frameworks and one another. I wrote memos to track my process and record notes about the participants’ processes as they described their experiences. Scholars have pointed out the value of writing memos throughout the data analysis (; ; ). Specifically, () argued that

Memos give you a space and place for making comparisons between data and data, data and codes, codes of data and other codes, codes and category, and category and concept and for articulating conjectures about these comparisons.(pp. 72–73)

During the final coding phase, I continued this iterative process to understand my participants’ experiences better. In addition, I began to explore the links between subcategories and the significant themes that began to emerge. This process involved asking what narratives were described, from where or who did these narratives emerge, and how participants responded to these narratives. These led to the three major themes of the study: there were multiple narratives considered, specifically those around Asians, Asian Americans, and Americans in the U.S.; participants were particularly focused on master narratives dealing with cultural expression; and participants’ personal narratives involved a complex process of internalizing master narratives while simultaneously living or actively creating alternative narratives through resistance. The analysis of data ended when theoretical saturation () was reached.

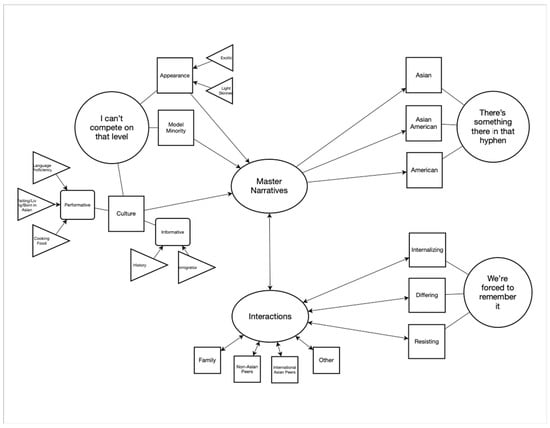

The first major theme emerging from the data was that culture was not restricted to their ethnic backgrounds but included the negotiation between U.S. cultural values and their ethnicity. Thus, participants’ experiences demonstrated how master narratives were created at both the macro level, such as the model minority, and the meso-societal level, where ethnic traditions and values also played a significant role in how they conceptualized their identity. The second major theme revealed how culture itself included both performative aspects, such as language proficiency, and informative aspects, such as knowledge about the history and immigration patterns of their ancestors. The third theme to emerge was how participants responded to master narratives that held meaning during interactions with others. Depending on the situation, participants either internalized, differed from (simply living an alternative narrative), or actively resisted the master narrative. Figure 1 illustrates the connections between codes, subcategories, and major themes.

Figure 1.

Code and major theme concept map.

The categories associated with each major theme are connected using a single line to illustrate the relationship. One-way arrows demonstrate how codes informed the broader category and overall theme. For example, categories included under “I Can’t Compete on That Level” indicated how those were the visible master narratives participants used when considering the Asian, Asian American, and Asian identities. Double-sided arrows indicate an ongoing and iterative relationship between the participants’ interactions between different groups or individuals and the master narratives they were considering during those interactions. Participants responded to the meanings they created or recreated during interactions with their social worlds by internalizing, differing, and resisting.

5.3. Trustworthiness

As the sole coder for this study, I relied on theory triangulation () and memos to establish credibility and trustworthiness. Scholars have argued that establishing validity and reliability in qualitative research differs from quantitative research () and must consider trustworthiness and credibility instead. () described one way to achieve trustworthiness: theory triangulation. Theory triangulation involves using multiple lenses or perspectives to analyze the data. In the current study, I employed a combination of master narrative (), symbolic interactionism (), and AsianCrit () to understand how participants negotiate socially imposed narratives in the construction of their identity. As each code, subcategory, and theme emerged, I considered them against each theoretical framework. In addition, I diligently wrote memos, a key component of () grounded theory method, which I used in the primary and secondary analysis. As stated above, memos provide a formal space to compare data to one another and data with emerging codes and themes. These and my continued reflexivity to examine my positionality throughout this process established the foundation for trustworthiness.

6. Findings

The purpose of this case study was to understand how Asian and Asian Americans negotiated master narratives in the construction of their personal narratives. The analysis of the data revealed three major themes. First, participants view Asian as a modifier of and distinct from American, which was associated with the adoption of and connection with U.S. culture. Under this theme, participants’ navigation of Asian, American, and Asian American narratives emerged. This highlighted the complexities of deconstructing monoracialism as participants used a cultural lens to explore their identity rather than race alone, which addressed the second major theme. When reflecting on their racial identity, Asians and Asian Americans referred to cultural values, traditions, and norms, suggesting that ethnicity and, by extension, informative and performative culture held significant meaning for identity construction. Third, participants’ personal narratives were shaped by a combination of internalized master narratives visible to them during the interviews and alternative narratives that either differed from or resisted master narratives. Experiences related to the model minority myth, perpetual foreigner, and physical characteristics played lesser roles in how participants reflected on their Asian and Asian American identities. While meanings behind the events varied with the participants’ interpretations, they did not dictate the negotiation of master narratives as significantly as culture. Additionally, the majority–minority environment did not impact the participants’ identity construction but was considered along with experiences before attending the university.

6.1. “There’s Something There in That Hyphen”: Complexity of Identifying as Asian American

A critical finding was how participants viewed their Asian and Asian American identities. Woven throughout participants’ reflections was their distinction between Asian and American. While the hyphen itself is no longer included in the writing of Asian American, participants still felt its presence as a modifier. A.K.’s comment, “There’s something there in that hyphen”, emerged during our discussion of her struggles with identifying as Indian American. She described her process as “fraught” unsure of how to label her racial identity and stated, “I didn’t know who I was for a number of years”. A.K. attributed this to living in the Midwest, where she was often the only student who was neither black nor white. She once discussed this struggle with her mother, who claimed, “You were born to an Indian stomach; you’re Indian”. This did not suffice as justification for calling herself Indian, and A.K. stated, “Blood only takes you so far”. For participants in the study, their main foci of discussion were not restricted to race but to ethnicity and culture. Both shaped their negotiation with macro-, meso-, and micro-societal level master narratives. After some time, she found her identity could be understood by how nationalities were referred to. She recalled,

Ultimately what helped me with identifying, coming to a place of identifying myself was Wikipedia. Cause I would look up people’s nationalities, and you know I noticed that distinction I noticed if the person was born in a certain country that lived in the U.S. were hyphenated, you know? There was that hyphenation that occurred.

For AK, to “embrace the hyphen” meant accepting the complexities in negotiating not just her blood and birth but the cultural values represented by both Indian and American society. When I asked her what it means for her to identify as Asian American, she stated,

So, what it, what it means to me really is just all things and their interplays, their flows, you know however they choose to call us in given moments. That obviously we perceive as moments, but depending on our own, you know positionalities. It’s not something that I can define easily, obviously.

A.K. pointed to key aspects of being racialized in American society when she referred to “however they choose to call us in given moments”. This comment pointed to the tensions Asians and Asian Americans must navigate when thinking about their identity and how narratives told at the macro-societal level are considered against their ideas and those of micro-societal groups such as family. A.K.’s struggle to define her identity speaks to the process of rejecting and aligning oneself with master narratives. On the one hand, U.S. society has imposed categories of who belongs and does not belong to the Asian group, or in A.K.’s case, the Indian population. On the other, she has familial/cultural narratives dictating who she is, as evident in the exchange between A.K. and her mother. During the interview, A.K. also discussed the narratives created around the challenge of handling different meanings of identity, which Nittha also expressed. However, her experiences demonstrated how participants could embrace their hyphenated identity.

Nittha immigrated to the United States, specifically Sun Valley, at the age of four but was still considered an international student by the university. In this, she found a built-in cohort of students who identified as Asian and with whom she could connect easily. These connections, along with her strong connection to her Thai background, supported by her mother’s close-knit group of Thai friends, helped her associate positive meaning to her identity. Nittha’s retelling of her experiences before attending SVSU highlighted her efforts to balance those aspects of her Asian American identity. She recalled a conversation in which her mother had acknowledged the availability of different religious practices in the United States. Nittha’s mother had assured her she could choose whatever religion suited her sensibilities. Nittha responded, “I enjoy being a Buddhist. Like I feel like that’s who I am. Like that’s what I grew up with that’s what I’ve known for so long. I don’t wanna like change it”. Although acceptance of her hyphenated identity evolved, she acknowledged the benefit of embracing Asian and American. When thinking back to the racism she encountered during elementary school, Nittha noted,

I remember I hated being Thai, like “Oh my gosh why do I get bullied so much? Why wasn’t I like just born here and just you know be American. So, I would look American at least”. But now I really appreciate the diversity because I get the best of both worlds. And I pick out the good in each of them.

When asked what Asian American meant to her now, after reflecting on her experiences before attending SVSU and as a current student, Nittha expressed feelings of appreciation and balance in her exposure to the Asian and American cultures. She stated,

For me being Asian American means being diverse-rich and well-rounded. That we’re able to appreciate both, two different countries, America, and Thailand or Asian or wherever. It’s just being able to see through both eyes that OK, “This is how American views life and in Asia this is how we view life”, and then compare and contrast like two different things. And just pick and choose the best that fits for you and whatever, you feel comfortable doing. It followed that Asian American identity could not be viewed without considering how they have navigated both racial and cultural dimensions of identity in Western society. As noted above, A.K. felt that Indian and American cultures played a critical role in declaring her Indian American identity. Culture was discussed by all participants in relation to how they negotiated their Asian American identity. It served as a baseline for gauging their “Asian-ness, “especially when considering their interactions with Asian international and other Asian American students.

6.2. “I Can’t Compete on That Level”: The “Thing” in the Hyphen

Participants described a complicated relationship with their Asian and Asian American identities indicating multiple master narratives to negotiate. Harry Potter (HP), who chose her pseudonym to represent her biracial identity, spoke explicitly about these narratives stating,

I think being Asian is more complicated. I think, like there’s culturally Asian, there’s Asian that’s like, like international Asian. I feel like there’s divisions in what the idea of Asian identity is, that’s more, it’s more fragmented or more fractal?

As noted by H.P., this negotiation involved a decidedly cultural perspective that illustrated how participants considered their ethnic and racial identities beyond those of phenotype. Culture significantly shaped how participants viewed their Asian and Asian American identities. This was ultimately the “thing” in the hyphen. As stated above, participants considered both U.S. culture and those specific to their ethnic groups. In turn, the ethnic group culture was further complicated by participants’ ability to “use it”. Participants consistently compared their level of cultural “knowledge” or “use” with those who were raised in Asia. This included comparisons occurring during interactions with international students attending the university, family members, or individuals living in an Asian country they were visiting.

Participants’ reflections on culture fell into one of two categories, informative and performative. Informative culture represented knowledge of history, pop culture, immigration patterns, and other related facts to the Asian continent and its people. While performative culture was most often related to language proficiency; it also represented practicing religion and living in or visiting their family’s country of origin. Culture held meaning for participants as they used it to determine their “claim” to their Asian identity. Interactions with Asian international, Asian American, and non-Asian students provided context on how participants considered their identity, which was further complicated by experiences outside the university setting. Most often, these interactions involved family and the cultural expectations upheld in those settings. Culture was also significant for biracial participants who felt their non-Asian identity mitigated their Asian identity.

6.2.1. Informative Culture

The findings related to informative culture centered around the “knowing” of various areas related to Asian history and culture. Stephanie, who identified as biracial Japanese white, described her experiences taking an Asian Studies course, emphasizing her lack of knowledge regarding the different Asian cultures. She mentioned, “I thought stupidly being Asian made me almost an expert at being Asian? But clearly, I know nothing about being Asian. I don’t even know anything about being Japanese really”. Stephanie’s experiences represented a personal expectation where she associated knowledge with “being Asian”. Other participants, such as Renee, had expectations imposed on her by others.

Renee, whose experiences as an adoptee were singular to the study, echoed the experiences of other participants who were expected to “know” about aspects of Asian culture. She described an incident with a multiracial Hispanic White peer whom she nicknamed her “spicy egg”. Renee talked of moments when he attempted to express his knowledge about various Asian cultures to impress her Asian international friends and to go so far as to attribute their friendship to his desire to “elevate his status, like “I know more than an Asian does”. She described his behavior as positioning her as a “dumb Asian” due to her lack of knowledge of Asian history. She recalled a particularly frustrating moment when he called her out for knowing little about the Ming Dynasty,

He sat next to me and he’s just like, just out of the blue, “Renee, what do you know about the Ming dynasty?” It’s always the fucking Ming dynasty for some reason. I’m sorry, but it’s always the Ming dynasty for some reason with these people. I was like, “I don’t know, I think it’s when the terra cotta army was made” And he’s like, “Oh no, that’s the other dynasty”, or whatever the hell it is. And he’s just like, “How do you not know when the terra cotta army was made?” Why should I know that off of the top of my head? It came off as that point of like, “You should know more about your own history”. It was like slap to the face comment like subtle comment that he tried to make. But I was like I can see past your subtle comment dude. That’s a fuck you moment right there.

The expectation to know everything about Chinese history, primarily when the participant viewed it as irrelevant to the conceptualization of her Asian identity, demonstrates how culture and the expectations created via narratives reinforced monoracialism.

6.2.2. Performative Culture

Enacting cultural traditions was important to participants and heightened in those who felt they could not do so. Language proficiency emerged as the main focal point in participants’ reflections on performative culture. Again, Stephanie referred to her lack of proficiency in Japanese as a personal disservice to herself. While discussing her motivations for taking a course through UTRP’s Asian Studies minor, she stated,

I’m doing myself a disservice by not knowing more about my heritage. People always ask me, have you been to Japan? Do you speak Japanese? And I say, “No. I haven’t been there. I don’t speak the language”. So how I could even call myself a Japanese American? Is kind of, like a big question mark for me now. I think I think I could be doing a better job representin’ my people.

H.P. considered how she fits within the overall conception of what an Asian American is, she noted,

I can’t compete with that level of Asian-ness. I do think that there’s still a desire to grow and become more aware of this identity. Cause I-I don’t know if that’s, arbitrary or not because it’s just like I have these genes. Is it weird to be, wanting to know more about those cultures, just because I have genes like that? Is it kind of an imposter thing. Is it like those weird white kids who watch too much anime and then all of a sudden want to be Japanese, all those things. I guess that’s kind of my fear is that I’ll, have that weird obsession, fetishization of the culture. Even though I’m part of it?

Their interactions represented how Asians and Asian Americans could maintain and reinforce preconceptions of who Asian Americans are. Participants placed significant meaning on cultural aspects such as food, language, history of immigration, and having spent time visiting their respective Asian countries. Lewis’s comments regarding the Filipino culture and identifying as a Filipino represented how even among Asians and Asian Americans, the idea of practicing cultural traditions was a significant part of identifying as such. He remarked upon his experiences with extended family and how their idea of being Filipino is diluted. He stated, “I had some friends and family in California that by the third generation was completely American”. For participants like Lewis, there was not so much a making but an unmaking of Asian. He went on to note, “You’re still Filipino cause you still take part in the group, even though personally you don’t practice it. To me you’re still Filipino, you’re not really Filipino. It’s like you’ve been diluted”. When considered against this benchmark, it reinforces Renee’s and H.P.’s hesitancy in defining their Asian American identity without practicing aspects of their culture.

Participants described possessing knowledge or, as Amelia states below, “having culture”, as a key part of identifying as Asian American. Amelia described her interactions with other Asians who marginalized her for her physical appearance and her lack of “knowing”. Commenting on the challenges she has faced, Amelia noted,

I feel, a certain amount of uncomfortable with certain groups. Like I feel like I don’t have any Asian culture and I feel like I don’t look Asian at all? So if I talk to another Asian, trying to be like, “Oh yeah, my grandma’s Asian too”, like they’ll just be like, “You’re not really Asian”.

The impact of interactions with others shaped how participants viewed their Asian American identity. For example, when looking back on her time before attending SVSU, Renee mentioned how her past interactions with Asian exchange students called into question her identity as an Asian American. She stated, “The other Asian students that I did come in contact, they were like the Asian foreign exchange kids. They were like full-on what I identify as Asian. So, it’s like I couldn’t even compete on that level”. Over time, however, she began to construct her personal and alternative narratives regarding her identity.

6.2.3. Appearance and Intelligence

While physical appearance and “being smart” contributed less to the participants’ understanding of their identity, these master narratives still played a significant role in how they viewed being Asian and Asian American. Biracial students and those who did not “conform” to society’s standards of what an Asian should “look like” expressed frustrations with how others presumed to categorize them as “non-Asians”. When it came to the model minority stereotype, which was most often linked to intelligence in the university setting, participants self-disclosed their inability to fulfill this expectation and prefaced their identity with comments such as “I’m not good at math”.

For racialized individuals, such as Asians and Asian Americans, the idea of consistently “seeing” their race, or being shown their race dehumanized their experiences. It relegated them to the boxes constructed by macro-societal narratives. Amelia, for example, identified as Japanese Black and talked about instances in which she was introduced “race first”. She stated, “Sometimes I’ll be introduced with my race. Like Amelia, and she’s Black and Japanese and that’s so weird”. For Amelia, racial identity was a barrier to being seen as whole, “I feel like race shouldn’t be, labeled as often”. Stephanie, on the other hand, wanted to be recognized for her racial identity. Identifying as Japanese White, she felt her physical appearance detracted from her Asian American identity. Stephanie observed that, “I think because I look Hispanic, I am kind of lumped in with the masses”. In being “lumped in” she felt her experiences as an Asian American were overlooked. In this instance, racial identity was signified as necessary in advancing and sharing diverse experiences in her class. Stephanie stated, “Maybe they would ask for my impressions of things from a different perspective, because I would have a different perspective not being Hispanic or Latino”. Appearance also extended to participants identifying as a single Asian ethnicity that did not fit the ideals. Lourdes described the frustrations she experienced with others choosing her racial identity.

It doesn’t fit into those neat little boxes that we’re required to check in demographics and the like. And that’s understandable. So, grew up you know talking to parents, like “Ok, do we count as Pacific Islander? Do we count as Asian?” Because, again this misconstruance that being Asian is more like being East Asian. And so, when I had transferred over to Silver City, there were a couple more Asian Americans within the community. One was half Japanese, half Mexican. And it was interesting because people more identified her as Asian because she had, you know the paler features, the high cheeks, what they had seen in media, etc. etc. And so they would look at me and be like, No you’re not Asian, you’re Mexican.

Having their agency stripped by being racially categorized by others extended to marks of intelligence or the model minority. Andy described their anger at how others devalued their academic efforts. Speaking of their time prior to attending the university, Andy mentioned,

So I used to be really intense about school but like I would struggle a lot? When I took harder classes I didn’t get A’s all the time right? People would tell me, my parents as well, who are in an interracial relationship, “Oh that’s only because you’re half Asian, that’s why you’re not all the way smart, or whatever, and they would tell me that and other people would tell me that and I’m like, … thank you for that vote of confidence. Total huge blow to my ego.

After attending the university, Andy felt that their perceptions changed regarding their responses to this socially imposed narrative, “Now I’m like, ‘You’re just being an asshole,’ like model minority is garbage. There’s such a diverse range and it’s so unfair to be like, ‘Oh you’re only smart cause your Asian’”. This finding was directly related to how monoracialism is currently considered. Individuals are restricted to the racial categories created by the U.S. government and how macro level society forces individuals to choose one identity or the other. For biracial Asians and Asian Americans, this only compounds the complexity of identity as they must negotiate the multiple master narratives associated with each racial and ethnic identity.

6.3. “We’re Forced to Remember It”: Visible Narratives and Alternative Narratives

During our interview, Noelle mentioned, “I forget that I’m Asian sometimes” when talking about her interactions with non-Asians. She described how her race was not at the forefront of her mind each day but was made more visible when interacting with others. Specifically, she stated,

I think as people of color, we’re forced to remember it and we’re reminded of it when those microaggressions come up. Or once somebody doesn’t get something that you get. I think that’s when it comes up.

Ultimately, participants’ construction of their personal narratives and their identities involved an examination of those master narratives most visible to them. Visible narratives referred to the master narratives that were relevant to participants’ experiences as Asian and Asian Americans in the U.S. at the time of their interview. Alternative narratives referred to how participants described either a differing from or a resistance to these master narratives. As mentioned above, culture significantly influenced how participants thought about their Asian and Asian American identities. In addition, while the role of the model minority and physical appearance played a lesser role in their construction of identity, these narratives also served as foundations from which participants lived or developed alternative narratives.

Language was the most significant aspect of the Asian and Asian American narratives that participants used to construct their personal narratives. The master narrative around language was that those identifying as Asian and Asian American would be proficient in their respective language. This narrative was reinforced at the micro-societal level during interactions with international students, family, and others outside their social or immediate circle. Stephanie’s reflections on being asked whether she can speak Japanese also demonstrated how language proficiency is reinforced during interactions with others. Although she used a general term to refer to her experiences, her comment, “People always ask me if I’ve been to Japan? Do I speak Japanese?” pointed to the interactions that informed her construction of who an Asian or Asian American is, which supported the internalization of the master narrative that Asians and Asian Americans must speak the language. Differing from this, Stephanie lived the alternative narrative of a non-Japanese language speaker, who may have been born to a Japanese mother but who also did not “look” Asian. This created a personal narrative fraught with the insecurity of her perceived ability to claim her Japanese identity for her own. This was evident in how she expressed that “calling herself Japanese” was one in which she was in the process of reconciling by enrolling in courses through the Asian Studies minor. Noelle also described interactions with a general “they” and the master narratives around language proficiency that were imposed upon her Asian American identity. As a fourth-generation Asian American, Noelle spoke of not speaking either Korean or Japanese but that there were assumptions immediately imposed upon her by others. She stated,

I think people, assume that because you’re Asian American that you act a certain way or you believe a certain way. For instance, whenever I use Spanish, people are very impressed and they’re like, “Oh! So, how many languages do you speak?” You know assuming that I speak an Asian language. and I don’t! I’m fourth generation Japanese and Korean, I don’t speak any Japanese and Korean except for like basic words. But people automatically assume you must?

Noelle related to these instances as reinforcing the perpetual foreigner myth. For Noelle, although she was living an alternative narrative, her identity construction relied on something other than language proficiency. When asked what being Asian American means to her, she stated,

It means pride. Pride and struggle, especially having studied Asian Americans, having been an Asian Studies minor, I learned about the history of Asians in the U.S., I learned about colonialism in Hawaii. It’s all been a history of oppression and that was the basis for it. But the fact that we survived and struggled and fought? We’re still here. It makes me proud, makes me very proud. When I think what does Asian American mean to me? I think of family. My family is so important. And obviously with Asian Americans, it’s closeness it means family. So, pride, struggle, family.

Andy’s experience visiting family in China revealed another way the language proficiency narrative could be reinforced during interactions with others. When describing who takes their Chinese identity at “face-value”, Andy recalled a moment when a Chinese couple expressed their pleasure at their proficiency in Chinese. They recalled,

I feel like I’ve had to prove my Asianness. I feel like, the p- like the group of people that were most accepting, that just took it at face value were like when I visited family in China, and like I remember this old Asian couple. Like we were out sitting next to them on the train, and we were talking and I was like, “Oh yeah my mom’s Chinese”. They were like, “Oh wow your Chinese is so good! We can totally tell”, and I was like my Chinese isn’t that good, but I’m glad that you guys are like having fun.

Andy negotiated between their alternative narrative (“my Chinese isn’t that good”) and the master narrative of language proficiency. Earlier during the interview, they described how they felt that being biracial gave them the “credentials” they needed to speak out against micro-aggressive or racist comments.

I don’t know if I should have been doing this, but I was at the bar with my friends and there was some guy who was all talking about, “Oh yeah, I know so much about the Korean language because…” something about Chinese and the languages are so similar. I was like, “Ok, I don’t speak Korean and I bare-speak Chinese very little, but, ‘No’”. I guess I was using it like a credential.

Andy’s prefacing of their ability indicated an active negotiation between internalizing language proficiency and living the alternative narrative of a lack of language proficiency. They mentioned it again during the interview when describing an incident where a white peer asked them about their language proficiency in Chinese, “She was like asking me if I spoke Chinese in Chinese? And I’m not going to repeat in Chinese ‘cause I feel really embarrassed about my accent”. Andy demonstrated how Asians and Asian Americans could create alternative narratives by minimizing the internalization of the master narrative. This differed from Stephanie, who lived an alternative narrative that created an internal struggle to construct a personal narrative reconciling master, alternate, and personal narratives, and Noelle, who resisted the language proficiency master narrative. Noelle was secure in stating those attributes that held meaning for her and her Asian American identity. Rather than struggling to reconcile with her lack of Korean and Japanese language proficiency, she openly called out the systemic oppression connected to these master narratives. Her proficiency in Spanish and the decision to become proficient in Spanish also demonstrated a resistance to the master narrative that ethnic identity and language proficiency go hand in hand. Others like Renee, Kathy, and Eric actively resisted master narratives in constructing their identity.

Master narratives about appearance emerged for Renee, who described peers commenting on her looks and even the sound of her voice. She described comments such as, “You’re really tan for an Asian”, and “Wow you have a really low voice”. Her responses to comments like these demonstrated an active resistance to master narratives foisted upon her by others. When addressing her skin tone, she recalled replying, “Am I supposed to just be white all the time? Like lily white. That’s what they call it, lily white. Am I supposed to be lily white all the time? With veins popping out everywhere for you to see?” When addressing narratives around her voice, she stated, “What, did you expect it to be nice and squeaky?” These conceptions of Asian and Asian American women extended to interactions Renee experienced on campus. She discussed an incident that occurred on the day of and prior to our interview, recalling,

Even today when I’m just sitting alone by myself in the student union, listening to music, some guys will just come up to me, and they’ll try and like act cool about it. But they’ll try and use like either Chinese or Japanese on me. They’d be like, konnichiwa, and I’ll be like, “Can I help you?”

Renee attributed this behavior to the portrayal of women in anime going so far as to say these individuals expected her to be “Nice and meek” a master narrative associated with Asian women who continue to be exotified by society. As mentioned earlier, Renee’s singular experience as an adoptee offered a different perspective on her connection to her Chinese culture. She stressed her greater affinity to being American and demonstrated that by actively resisting master narratives during these interactions, she was creating her alternative narratives to expectations of who Asians and Asian Americans are.

The master narratives visible to Kathy involved the differences she observed between what she referred to as traditional Asians, international Asians, Asian Americans, and U.S. Americans in general. Kathy’s focus on traditional versus liberal expressions of culture was part of her negotiation between master narratives, alternative narratives, and identity. She positioned herself outside of U.S. American culture, stating,

I’ve come to notice more of like how difficult I am compared to like, a majority of the United States, ‘cause I feel like people are more liberal than I am. Like I’m liberal, but there’s certain policies that I’m liberal about.

When discussing how she felt as the potential Asian spokesperson for her peer group, Kathy noted,

What I feel is that it’s not for all Asians, but it’s for the traditional Asians. I would explain to them there’s Asian Americans, but there’s also like, for instance, Asians who are, the youth from their own country, like the internationals, but, because of the way they’re raised now um, depending on how their raised actually, are still different from traditional Asians. For instance, I was born and raised in California, but my mom was super traditional, so hence, she tells me now, “You know you’re a really difficult person, so it’s gonna be hard for you out there”, and I was like, “Ok whose fault is that? Like you raised me to be this way”. She learned from her like children and her grandchildren back home to kind of be more loose and be more accepting, of like different people’s actions, and what not. But I have not learned to be that way, whereas like um, my my godmother’s granddaughter, came from Vietnam recently, but she was raised in Vietnam, but her family was so loose as in like they’re not as traditional, so she dresses up kinda showy you know. More skin here and there and like a lot more makeup than I would and it’s different. So, I do explain to people now it really depends on the parents and if they kept their traditions or not.

Kathy explicitly resisted the master narratives of “showy”, “liberal” Asians, Asian Americans, and Americans. She prided herself on maintaining traditional Vietnamese culture. She spoke of growing up on the West Coast and how her community gathered to plan the Tet Festival. Kathy fondly recalled sharing myths and legends, the Vietnamese community’s history, language, and food. To Kathy, these were essential narratives in her identity construction. While these narratives, when viewed from the perspective of other participants, presented a conflict between negotiating master narratives as they connected these to individuals who had deeper roots, Kathy internalized them. She shifted her alternative narratives to focus on the ways she resisted the liberal and American narratives of both international Asians and Asian Americans. When describing her experiences with a group of international Asians during a trip, she stated,

For internationals, I don’t really click with them. I, I’ve only been exposed to some, I don’t believe I’ve been exposed to all international Asians here, but for the people who I did go to the mountains with, I didn’t really click with them, they were a lot more girly, but like hottie.

Kathy’s alternative narrative positioned her as traditional, feeling she fit neither the Asian nor American master narratives. Eric also demonstrated a resistance to the American master narratives associated with those born and raised in the U.S. When asked what he felt it meant to be Asian American, Eric stated it was to be part of the “in-group”. He clarified by stating, “Like a European white background and everything. I mean that’s what it means to be American”. Eric could not identify as Vietnamese American and instead rejected the hyphened narrative. He expanded on his thoughts, explaining,

For me to say I’m Vietnamese, it gives me a sense of being like separated you know? I like being an individual and I like being unique. I don’t understand why if I were to say I’m Vietnamese, why I have to hyphenate it, with being Vietnamese American. Why is it that I just can’t stand and identify as my own race? Or as my own culture and everything? Instead of with America to be like this part of mainstream society. If I feel like if we were a fishbowl, and everything, then why can’t all these different races stand separate, but yet still be together. You’re hyphenated to be underneath this umbrella of what it means to be American and everything. So whenever I say I’m Vietnamese I’m just only Vietnamese. I think it’s, like giving a sense of pride to people who, like my ancestry and everything and my heritage and my culture and my language and all that. I don’t feel like it has to be hyphenated with being American as well. But to me it gives me a sense of being separated, a sense of like independence and a sense of pride over what my what people who are Vietnamese been through and everything.

Eric mentioned that he had never visited Vietnam but still felt the connection with his culture from the traditions and narrative shared within his family. This strong connection served as a foundation for resisting the hyphenated master narrative involved in being part of the American “in-group”.

7. Discussion, Limitations, and Conclusions

Asians and Asian Americans in the study demonstrated that deconstructing monoracialism was more complex than examining the role of race, racism, and oppression. First, deconstructing Asian and Asian American involves negotiating narratives associated with the Asian, Asian American, and U.S. American identities. Second, these narratives involved cultural expectations. Third, the master narratives with which participants engaged varied according to which was most visible at the time of the interview. () stated, “This means that for those in the position of violating master narratives, or who are engaging in greater degrees of personal negotiation, master narratives are not likely to be invisible”. (p. 327). This concept was critical when examining how participants in the current study engaged in the deconstruction of monoracialism. Their experiences involved the visibility of master narratives that the U.S. dominant society imposes on Asian and Asian Americans.

An unexpected finding was how the model minority and perpetual foreigner myths played lesser roles in deconstructing monoracialism through the negotiation between master and alternative narratives as they constructed their identity or personal narratives. While every participant mentioned the model minority explicitly and alluded to the perpetual foreigner stereotype, these did not hold as significant a place as did cultural expectations on how to behave as a member of their respective ethnic Asian community. () noted that master narratives may be created at the cultural level, demonstrated by how participants responded to the question, “What does it mean to be Asian American?” Specifically, they referred to language proficiency or, as Michael noted, “Having roots in Asia”. As stated above, master narratives inform individuals how to be “good members” of society. In this study, being “good members” involved participating in and embodying the cultural traditions of Asian and Asian Americans’ respective ethnic groups, specifically focusing on language proficiency. The findings revealed that these narratives were not the sole creation of the individual but were reinforced in their interactions with others. They were foundations from which Asians and Asian Americans could internalize or resist these ideas, thus creating alternative narratives.