Blurred Edges: Representation of Space in Transgenerational Memory of the Nazi Euthanasia Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Transgenerational Memory in the Family of a Nazi Euthanasia Victim

Gina:11 I was about 18 years old, at the time. I didn’t know there was a secret in the family, until my father said that his mother was mentally ill, suffering from schizophrenia. I laughed, thinking, “What a family! I have an eccentric grandmother, and you never told me about her!”, I didn’t understand the true significance at the time. I was in a fight with my father and didn’t consider how he must have felt, his feelings. This realization came later. I couldn’t imagine how he felt as a child, so I couldn’t recognize what was behind the story. My father was seven years old when she died, but he had not seen her before either, as she was often hospitalized and, in 1940, was admitted in a special closed section and never came home.Hannah: I found out earlier, when I was 16 years old. He told me she had died and I asked if she was murdered by the Nazis, as I had heard about that in school. We talked about euthanasia. He answered, “Nobody knows”, as she had a disease. When we found her medical file, it says (showing the document) that she died of a “heart attack”. But last year, searching on the internet, I learned that this was often written when a patient died of starvation.G: But she was really schizophrenic.

G: Our father knew that she died in Neuruppin. He had this document about her, the “Totenschein” (death certificate), but he was not sure about the cause of death. He had two siblings and one older sister who was five years older. She asked their father, after the war, if it could be that she died of heart disease, as she had never had one before, so she thought their mother was killed. But our father, who was five years younger, wasn’t so sure. So, in the family, they didn’t think she was murdered, but that she was… brought to death, how to say. They had no real evidence. Our father started searching for her file, I think it was around 1970, and wrote to all the hospitals where she had been. He was the first one who wanted to know the truth.H: It was after the Berlin Wall came down that he wrote to the clinic in Berlin Lichtenberg, where she was from 1938 to 1941, the Evangelisches Krankenhaus Königin Elisabeth Herzberge, but they said, “We have nothing. No files about her”. Then, he wrote to Neuruppin, which also had no information.

H: The Director of the clinic spoke with us for two or three hours and said we were the first people to ask for files. It was in 2003.G: I knew my father had ask before, and I am sure that many others had done the same! The Director was born after the war, so it wasn’t his fault. But he felt that he was representing the hospital and he knew the Doctor who wrote the death certificate, he was still alive! I don’t know if he really was the murderer of my grandmother, I can’t say for sure. But he signed the documents and it was his responsibility to take care of the patients, to ensure that they were living in the proper way…H: …and not be killed.G: Yes, to take care of them. So, I started to do research, and asked Hannah to join me. I didn’t want to go to Neuruppin alone. I felt very… it was so… cold. To visit that place knowing that my grandmother died there… under such circumstances, starving and left alone by the doctors and others who were supposed to take care of her… but she was not the only one. Many people died there. It was very difficult to visit that place and see all those windows closed, like a prison.

H: When Maria left Papenburg and her family, she went to Hamburg.G: She gave birth to her first child and suffered from postpartum depression. For half a year, she stayed in a clinic, and our grandfather went to Berlin to work for the Christian workers’ syndicate. He was very religious and made a career for himself. Berlin was the centre of that organization and he earned some money. He decided to take his wife back with him and rented a house in the suburbs, with a little garden. There, their second child arrived. It was a nice life…H: For almost ten years, life was nice. Then she was hospitalized again in a clinic.G: …but times changed. She started to go back and forth between the clinic and home. It was a private hospital in Berlin, near Bernau. I think it was just too much for her.H: She had the feeling of always being observed by someone behind her, looking for her.G: It’s all written in her personal file.H: Then, in 1938, the family’s doctor declared that she was schizophrenic and had to be hospitalized again. The doctor was not an expert, just a regular one. It was the summer of 1939.H: The doctor at the clinic requested her sterilization, but she was not sterilized. Our grandfather went to the Gesundheit Gericht to claim against it. It was the same place where I had my first case when I was a lawyer!G: Yes, the same place! It’s strange… it’s so strange! I also worked in a laboratory in the same clinic in Lichtenberg where Maria was. It was a lab about eugenics… so strange.H: In the end, they declared that sterilization was not necessary because she already had three children and would have no more.H: I think the family’s doctor knew about the euthanasia program.G: He had to. There was a law, it was impossible to say “no”.H: The problem, in our family, was that our grandfather went to war early, in 1939, right at the beginning. He had three children and no one to take care of them.G: He had to find someone to take care of them. Their mother was in the clinic. There were different women, one after another… it must have been very difficult for the children.H: But he came back soon. Somehow, he was able to stay in Berlin. Maybe because of the children had no one to take care of them? We don’t know.G: He wrote a lot of letters to the doctors. We have them all in the files. It was very interesting to read them: “What’s going on with my wife?”, “Is she ok?”, “When will she come back?”. He was concerned, and visited her regularly, on Sundays, but without the children, in Neuruppin.G: Then, we found another file, the first one, with all the descriptions of how she was behaving. It was very cruel… she was so upset and wanted to take her life. She was full of fears. I think something very bad must have happened to her.H: We couldn’t explain it. One day she went to Church to talk to the priest and confess. After two weeks, she said what she told him wasn’t right. Did she lie? Then, her father took her to a clinic, saying she was looking for a knife to kill herself. It’s all written in the file. But we don’t believe her feelings of guilt were generated by the “false confession”. There must have been something… something happened, for sure.G: …an attack on her. She was only 17 years old… maybe in a sexual way? That could be the reason.H: But these are just our thoughts. We have no proof.

G: She was really ill. I think he couldn’t understand that she could be in danger and even be killed there. He just trusted the doctors.H: They believed in physicians. When a doctor said, “You must do this”, then they did it. This was the strategy of the Nazi.G: And it worked. Most people didn’t realize that until the moment when the papers came: “Your wife died of a heart attack”, but she never had heart problems! Then, people started asking…H: This was the time when T4 program was officially stopped, but it continued secretly. Von Galen spoke about it. He said that the Nazis would kill even the wounded soldiers, and so people started to stand up.

G: She was losing weight while she was in the hospital. There’s a weight table in the file.H: She lost 30 kilos in just three years.G: She lost weight until she weighed just 42 kilos. They let her die of starvation. But this page was missing from the file that Neuruppin gave us! An historian found it later and gave it to us.H: I don’t think the missing part was a mistake. I don’t think so.

G: It has always been difficult for our family to deal with this illness. Some relatives told us, “You will get the same”. So… you have to think about it when you get married and have children, because they said it’s hereditary.H: I was always afraid of getting it. When I was younger, this was the connection to Maria. I often had depression and my thoughts, especially when I was 17 or 18 years old, were: “If I tell someone I’m feeling bad, they’ll take me to a clinic, and in the clinic, they’ll kill me”. So, I said nothing, but there was the fear.G: So, we don’t talk about it. Only within the family, but not to others.H: When I wanted to get pregnant, I went to a doctor to ask about the risk, and my brother did too, but we didn’t talk about it to each other. It was a problem in the family.G: Everyone dealt with it on their own.H: We were afraid. Our aunt, Maria’s daughter, was always afraid, because of that. In school, when the teacher asked about her mother, she didn’t mention the clinic because she was afraid of being sterilized too: “If people find out that I, a blond girl with blue eyes, a perfect Aryan type, have a mentally ill mother... with a genetic disease!”

3. Zyklus für Maria as a “Memory Object”

“When I paint, I think about all and nothing. I follow my intuition and hope that it will lead me to a vision that I can understand and that shows me something—about myself or about the world in which I live. I don’t think of an observer during this process. But when I have succeeded in creating the work and I am happy, I wish to be able to share this happiness. And my happiness would be complete if my painting triggered an involuntary (beautiful) memory in the viewer, as Marcel Proust described it in his novel “In Search of Lost Time”. My painting leads the viewer further to something else—and thus perhaps also to a conversation with me. In this way, both sides reveal something of themselves and come closer to each other.”14

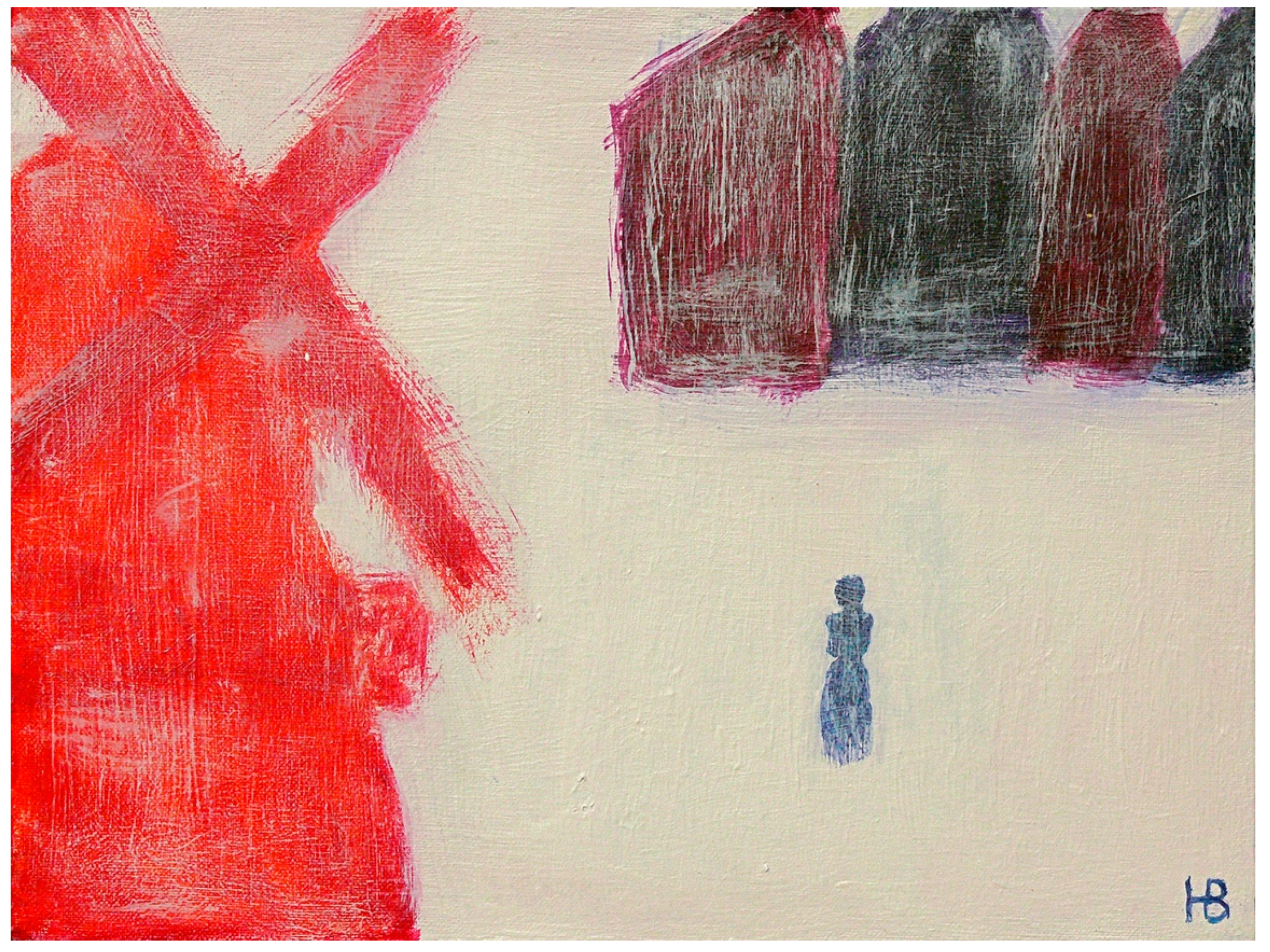

“My feeling is that Maria may have found the town cramped and even threatening after her hospitalization; she may also not have been able to talk to anyone about her stay in Osnabrück. She felt excluded, alone, abandoned. I wanted to show that fear and also that sense of being lost. This is how the idea for the painting came about: the city is dark, there is no way out, and this little person is alone in a large open space, while a dark and dangerous city awaits her on the horizon.”18

“When asked why Maria, Josef is reported to have replied: “Because she was the most intelligent and the most beautiful of the sisters”. It is strange that the civil marriage took place in Papenburg and the church wedding in Hamburg. Maria and Joseph were strictly Catholic; the civil marriage was not considered a “proper” marriage according to the ritual of the Church; perhaps the priest in Papenburg had refused to perform the marriage precisely because Maria was considered crazy.”19

“It has been remarked to me that there are many houses in my paintings and that Maria, this small human figure, is always in front of or in the middle of buildings. The house represents the feeling of being at home, the sense of protection one gets from being in one’s own home. A feeling that Maria did not experience when she was in hospitals and clinics. She certainly didn’t feel protected there, I think she was very afraid, and that is why in the exhibition in Osnabrück, where she was taken by her father when she was little more than a child, I decided to also display documents from her medical records, in which she is described as being very frightened and speaking in whispers, with her eyes wide open.”20

“At that point I realized that I had to portray Maria’s life, so I started to think about where she had been, which pictures to choose and I told myself that she had not always been ill, she also had an everyday life, she married, she had been loved, she had three children, she had not spent her life in hospital or in the grip of psychosis. So, I looked for photos of her, of her family, and found several. She was with Josef, or with her parents and sisters, and then of course some photos were taken in 1939, on her arrival at the Evangelisches Krankenhaus Königin Elisabeth Herzberge hospital. The classic frontal, profile, and three-quarters images were taken in those circumstances.”22

4. Conclusions

“After the first exhibition, others followed, also in Papenburg, where Maria was born and lived, in Osnabrück, in the clinic where she was interned at the age of seventeen, and in the last exhibition this year in Neuruppin, where she was murdered. The paintings were exposed in the monastery church. It was very emotional for me, because I saw it as the closing of a circle. In a way it was as if Mary had returned there, no longer as a victim, but as a human being.”24

“I think it is important to show the human being, who is not a number among others in the total of the victims, but it was her! She was one of the victims. A woman who was killed for no reason, a woman who was also happy, who had children, who was a beautiful woman, and who then became ill, but could have been cured. I wanted to show that, I wanted people to know that. And every time there is an exhibition, some people come and talk to me, thank me, and tell me that what I do is important. One woman, for example, told me that she had a post-partum depression, like Maria, but that she was fine now. She was happy with her children and could talk openly about it. I think this pushed me more and more to want to talk about the illness, which is present in my family, about my grandmother’s story, which is similar to the story of so many others. I think talking about it is important so that it can never happen again.”25

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The first European state to enact such a law was Switzerland (Canton Vaud) in 1928, followed a year later by Denmark. Similar measures were enacted in Norway in 1934, in Sweden and Finland in 1935, in Estonia in 1936 and in Ireland in 1938. Vera Cruz, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Lithuania, Latvia, Hungary and Turkey followed. |

| 2 | On the same day, the Concordat with the Catholic Church was also approved. To avoid complications with the Vatican, the law was not published until 25 July and took effect on 1 January 1934. |

| 3 | According to H. Friedlander in October 1939. (Friedlander 1995). |

| 4 | It was not published in the Official Gazette of the Ministry. |

| 5 | Ministry of the Interior Circular IV b 3088/39 1079 MIdR of 10 August 1939. Translation by the author. |

| 6 | As established by the Schwerin public Prosecutor’s Office in 1949. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Interview with Hannah Bischof, Berlin, 9 November 2022, in Author’s Private Archive (APA). |

| 9 | The interviews, audio and video recorded in Berlin by the author during 2019 and 2022, are conserved in the Author’s Private Archive (APA). All interviews were conducted in English and German. The translation of the extracts is by the author. |

| 10 | I used the same interview-scheme as for narrative-biographical interviews. See in particular the works of Gabriele Rosenthal: (Rosenthal 1998, 1993, pp. 59–91). This interview technique works with an initial narrative question, which leaves the interviewee free to choose the main themes. This personal choice constitutes a valid first element for the subsequent analysis. In the second part, more specific questions are asked, but always with reference to the main narrative. In the last part, the interviewer asks questions concerning topics that did not emerge during the interview. |

| 11 | All extracts quoted in this paragraph are excerpts from the interview with Hannah and Gina, Berlin, 12 June 2019, in APA. |

| 12 | About the “special diet” see: (Burleigh 1994, p. 229 and following). |

| 13 | “Die rote Mühle” (The red mill)—Papenburg 1905, 2012, 30 × 40 cm; “Die Abreise” (The departure)—Osnabrück 1922/1923, 2012, 30 × 40 cm; “Papenburg 1923–1927”; 2015; 100 × 100 cm; “Die Hochzeit” (The wedding), 2015, 100 × 100 cm; “Der Aufbruch“—Umzug nach Hamburg 1927 (The start—Move to Hamburg), 2012, 100 × 100 cm; “Ein neues Zuhause”—Leben in Hamburg 1928 (A new home—Life in Hamburg), 2011, 100 × 120 cm; “Gestörte Wahrnehmung”—Staatskrankenanstalt Friedrichsberg/Hamburg 1928 (Disturbed Perception—State Hospital Friedrichsberg/Hamburg), 2015, 80 × 100 cm; “Zwischenzeit”—zwischen Hamburg und Berlin; Aufenthalte ohne Kliniken 1929–1938 (In-between—between Hamburg and Berlin; stays without clinics), 2015, 100 × 100 cm; “Cardiazol”—Sanatorium “Heidehaus”/Zepernick bei Berlin 1938, 2015, 100 × 100 cm; “Die Konturen verschwimmen—Psychiatrie”—Klinik Herzberge, Berlin-Lichtenberg 1938–1941 (The outlines blur—psychiatry), 2015, 100 × 100 cm; “Die drei Besucher”—1938–1941 (The three visitors), 2012, 120 × 160 cm; “Innenhof mit dunklem Bett”—Neuruppin 1941 (Inner courtyard with dark bed), 2014, 100 × 100 cm; “Die Klinik”—Neuruppin 1941/1942 (The clinic), 2015, 60 × 80 cm; “Die Kapelle”—Neuruppin 1942 (The Chapel), 2015, 40 × 60 cm; “Die Särge”—Neuruppin 1942 (The coffins), 2015, 40 × 60 cm; “Kirchenschiff mit blauem Haus”—Neuruppin/Berlin 1942 (Church nave with blue house), 2013, 100 × 100cm. |

| 14 | Translation by the author. The original, in German, can be found at this link: https://www.hannah-bischof.de/vita/uber-meine-malerei/, Consulted on 2 November 2022. |

| 15 | In this essay, only some of the paintings are shown. All works can be found on the artist’s website: https://www.hannah-bischof.de/galerie/zyklus-fuer-maria/, consulted on 11 February 2023. |

| 16 | The German word Abreise indicates the general, theoretical concept of “departure”. |

| 17 | The German word Haustochter, in use until the first half of the 20th century, indicates a young woman who lived with a foreign family for a certain period of time, to learn how to run the household. |

| 18 | See note 8. |

| 19 | See note 8. |

| 20 | See note 8. |

| 21 | The German word Aufbruch indicates the concrete, initial part of a departure process. |

| 22 | See note 8. |

| 23 | Worthy of note, however, are the testimony of (Manthey 1994). Never translated in English, it has been republished by Mabuse Verlag in 2021. See also (Kaufmann 1999). |

| 24 | See note 8. |

| 25 | See note 8. |

| 26 | Cicero, De Oratore II 86, 353–355, in (Cicero 1942, pp. 466–67): “He inferred that persons desiring to train this faculty must select localities and form mental images of the facts they wish to remember and store those images in the localities, with the result that the arrangement of the localities will preserve the order of the facts, and the images of the facts will designate the facts themselves, and we shall employ the localities and images respectively as a wax writing tablet and the letters written on it.” |

| 27 | In addition to the statements and documents of the perpetrators, such as the medical files compiled in the euthanasia program clinics, in some cases, after the war, relatives of the murdered and survivors approached the judiciary and reported on their experiences. Concerning Hadamar, for example, see (Schneider 2020). |

| 28 | About Elvira Manthey see also: (Robertson et al. 2019). |

| 29 | About the literary memorialization of the Nazi Euthanasia, see: (Knittel 2013, pp. 85–101). |

References

- Aly, Götz. 2013. Die Belasteten: “Euthanasie” 1939–1945. Eine Gesellschaftsgeschichte. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Aly, Götz. 2017. Zavorre. Torino: Einaudi. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2011. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, Gisela. 1986. Zwangssterilisation im Nationalsozialismus. Studien zur Rassenpolitik und Frauenpolitik. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh, Michael. 1994. Death and Deliverance: Euthanasia in Germany 1900–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero. 1942. Cicero in Twenty-Eight Volumes. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander, Henry. 1995. The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. London: Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1950. La Memoire Collective. Paris: Presses Univ. de France. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Alois. 1999. Totenwagen. Kindheit am Spiegelgrund. Wien: Uhudla Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Knittel, Susanne. 2013. Beyond testimony: Nazi-Euthanasia and the field of memory studies. In The Holocaust in History and Memory. Edited by Rainer Schulze. Colchester: University of Essex Press, vol. 5, pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kühl, Stefan. 2013. For the Betterment of the Race: The Rise and Fall of the International Movement for Eugenics and Racial Hygiene. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Primo. 1956. I sommersi e i salvati. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Primo. 1958. Se questo è un uomo. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Manthey, Elvira. 1994. Die Hempelsche. Das Schicksal eines deutschen Kindes, das 1940 vor der Gaskammer umkehren durfte. Lübeck: Hemplel Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, Pierre. 1984–1992. Les Lieux de Mémoire. Vol. I “La République”, Vol. II “La Nation” (3 vol.), Vol. III “Les France” (3 vol.). Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, Pierre. 1989. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. In Representations, No. 26, Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Michael, Astrid Ley, and Edwina Light. 2019. The First into the Dark, the Nazi Persecution of the Disabled. Broadway: UTS ePress. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, Gabriele, ed. 1998. The Holocaust in Three Generations: Families of Victims and Perpetrators of the Nazi Regime. London: Cassell. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, Gabriele. 1993. Reconstruction of life stories: Principle of selection in generating stories for narrative biographical interviews. The Narrative Study of Lives 1: 59–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Christoph. 2020. Hadamar von innen. Überlebendenzeugnisse und Angehörigenberichte. Berlin: Metropol Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Weindling, Paul. 1989. Health, Race and German Politics between National Unification and Nazism 1870–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silvestri, E. Blurred Edges: Representation of Space in Transgenerational Memory of the Nazi Euthanasia Program. Genealogy 2023, 7, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010019

Silvestri E. Blurred Edges: Representation of Space in Transgenerational Memory of the Nazi Euthanasia Program. Genealogy. 2023; 7(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilvestri, Erika. 2023. "Blurred Edges: Representation of Space in Transgenerational Memory of the Nazi Euthanasia Program" Genealogy 7, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010019

APA StyleSilvestri, E. (2023). Blurred Edges: Representation of Space in Transgenerational Memory of the Nazi Euthanasia Program. Genealogy, 7(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7010019