Abstract

Traditional interpretations of Nietzsche’s The Genealogy of Morals (GM) argue that the work is a treatise on, or a straightforward account of, Nietzsche’s moral thinking. This is typically contrasted with what has become known as the postmodern reading, which holds that the core of GM is an attack on the very notion of the truth itself. These two interpretations are often taken to be non-coextensive and mutually exclusive. However, I argue, using a genetic form of argumentation that tracks the development of the text through archival evidence, that both are partially correct, since Nietzsche sees all fundamental problems hitherto as moral questions in service of the ascetic ideal and the will to truth. According to Nietzsche, all the hitherto fundamental questions of philosophy are not value-free but are deeply value-laden. To put this more precisely, Nietzsche rejects the fact-value distinction itself. Questions of morality are not separable from epistemology, questions of epistemology are not separable from morality, and both subjects have worked in service of the ascetic ideal. Further, I provide new evidence on the debate about the counter-ideal to the ascetic ideal. I claim that Amor Fati embodies that ideal. I argue for this using a section from the preface that was added but then removed. This section was removed because it gave away the conclusion of the work, that all fundamental problems, including questions of truth, are based on moral prejudices.

1. Introduction: Overview of Scholarship

“For all the value that may be attributed to the true, the truthful, the selfless, it would be possible that a higher and more fundamental value for all life would have to be ascribed to appearance, the will to deceive[…].”(Nietzsche 1966, BGE 2)

This paper provides a general overview of how genetic interpretation offers insight into historical texts. Genetic interpretation tracks the development and genesis of a text to shed light on the meaning of the final text of interest. This article uses the Preface to Nietzsche’s work The Genealogy of Morals (GM)1 as a case study of genetic interpretation. In this case study, I will argue that we can regard drafts of the genesis of the Preface of GM, and a section that was removed, not simply as botched drafts but as important evidence for interpreting GM. This section reveals that the argument in GM is not simply a critique of ethics or morality as scholars have traditionally ascribed to GM. However, neither is GM only about the will to truth at the exclusion of morality. Rather, questions of truth are themselves value-laden by the ascetic ideal. For Nietzsche, questions of epistemology and values are inseparable.

The structure of GM, as Nietzsche (1967a) describes in Ecce Homo (EH), is “calculated to mislead”. Nietzsche’s final target is the ascetic ideal and the will to truth. Nietzsche then suggests that the ascetic ideal is not the only ideal from which we can derive meaning. A counter-ideal that does not prioritize truth has been put forward in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Z). GM can therefore be seen as a continuation of Nietzsche’s epistemological attack on the priority of truth in Beyond Good and Evil (BGE) and simultaneously points us back to Zarathustra’s immoralism and counter-ideal. The aim of GM, therefore, is not simply a critique of morals, but also a critique of the will to truth and the ascetic ideal as moral phenomena.

I hold that GM is best interpreted not as a book on ethics alone, but also as a book on epistemology and the fundamental questions about how we create meaning. Although excluded in many standard translations, the first edition of GM actually had a line on the title page that read, “By way of clarification and supplement to my last book Beyond Good and Evil.”2 In BGE, the basic claim is that the assumption that truth is intrinsically valuable is founded on normative or moral values. However, in BGE, Nietzsche claims there are even “more fundamental values” than the will to truth (Nietzsche 1966, BGE 1–2, 4). In GM, Nietzsche continues this argument by claiming that the will to truth is not the value-free bastion of secularism we take it to be. All of our most fundamental problems in philosophy, including those in epistemology, have been a kind of moral value judgement; even our will to truth is beholden to the ascetic ideal and is therefore a kind of value-laden judgment. Nietzsche claims that the ascetic ideal has been the only ideal hitherto. The question is, if all philosophy hitherto has been a kind of moral blunder, how are we to go beyond that ideal? Nietzsche suggests that there is a counter-ideal, an ideal put forward by Zarathustra, that exists beyond truth, morality, and good and evil. I provide new genetic evidence that this ideal is related to eternal recurrence and Amor Fati.

2. Overview of Scholarship

Scholars tend to think about The Genealogy of Morals in two radically different ways: traditional vs. postmodern.3 The traditional interpretation takes GM to be about morality, while the postmodern interpretation takes the primary topic of the text to be our commitment to truth. The traditional interpretation understands GM as a text primarily focusing on moral action, rather than, for example, epistemological concerns with truth and meaning. As Richard Schacht states, “Traditional readings of GM tended to focus […] on its treatment of morality.” (Schacht 2016, p. 324). We can see such positions expressed in the work of Michael Allen Gillespie and Keegan F. Callanan, Daniel Conway, Robert Solomon, Scott Jenkins, Iain Morrisson, Mark Migotti, Ivan Soll, and, to a lesser extent, Lawrence Hatab. This is distinct from a second kind of reading that Schacht associated with postmodern or deconstructive readings that take GM to be a “subversion not only of morality but also much else in and about philosophy as we know it, from the concept of ‘man’ […] to the very ideas of truth and knowledge.” (Schacht 2016, p. 324). The philosophers typically ascribed to this view often apply Nietzsche’s genealogical method to their own projects. Philosophers typically associated with this position include Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Jürgen Habermas, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and Gilles Deleuze (Shapiro 1990, pp. 39–55).

The traditional view has been accurately summarized by Babette Babich, who argues that scholars have traditionally read GM “as a Tractatus or straightforward account of Nietzsche’s moral thinking.” (Babich 2006, p. 77). Such readings understand the topic of morality to broadly include moral psychology and philosophical–psychological analysis of the phenomenology of moral feeling. All of these tend to take morality or “ethics” as one among many different branches of knowledge or experience that specifically concerns itself with the principles that govern behavior. Morality concerns the questions about moral desserts for actions and the handing out of praise and blame, reward and punishment. On this view, neither logic, metaphysics, epistemology, nor mathematics are the realm of morality.

Richard Schacht is a classic example of a diligent scholar who consistently claims Nietzsche’s argument in GM is about morality. Schacht writes, “I take [Nietzsche] to be venturing a number of ‘conjectures’ and ‘hypotheses’ […] with respect to ‘the origin of morality’ as we know it.” (Schacht 2016, p. 324). Such a conclusion is also put forward by Michael Allen Gillespie and Keegan F. Callanan, who write, “At the core of [Nietzsche’s] argument is the revolutionary claim that all Western morality from the time of Socrates is merely a reaction to an earlier and original master morality that characterized the ancient world.” (Gillespie and Callanan 2012, p. 271). Other scholars such as Robert Solomon hold a similar position, claiming, “The genealogy of morals is, first of all, a thesis about the motivation of morality.” (Solomon 1994, p. 97). Several other scholars, such as Scott Jenkins, Iain Morrisson, Mark Migotti, and others, presuppose that the basic topic of GM is our everyday sense of morality in one form or another (Jenkins 2003; Morrisson 2014; Migotti 1998; Conway 2008, p. 5). Daniel Conway’s Nietzsche’s ‘On the Genealogy of Morals’: A Reader’s Guide also shares this view, and cites Nietzsche’s claim that this work is a continuation of his “thoughts on the origin of our moral prejudices.” (Conway 2008, p. 3). As Conway suggests, “In GM itself, as we shall see, [Nietzsche] wishes to demonstrate that these prejudices endow contemporary morality with a past that is far more complicated, far more burdensome, and far more interesting, than rival scholars have dared to suppose.” (Conway 2008, p. 3).

Such interpretations face difficulty when applied to the third essay of GM. Sometimes, their interpretations of the third essay simply avoid the topic of truth altogether. For example, Conway takes the central issue in essay III to be, continuing his reading from essay I and II, the origin of morality. He writes,

It is notable that the scholars here listed say little or nothing about Nietzsche’s discussions of truth in GM III, especially GM III 25–28. The very first line of GM reads, “We are unknown to ourselves, we men of knowledge—and with good reason” (GM pref. 1). This should indicate to diligent scholars that this text has something to do with epistemology and a genealogy of knowledge itself.In Essay III, [Nietzsche] reveals morality to be dependent on the ascetic ideal, which honors the life of self-deprivation as the highest standard of human flourishing. Finally, at the close of GM, he exposes the will to nothingness that morality both presupposes and expresses.(Conway 2008, p. 5)

Some scholars take the traditional approach and claim that the central feature of GM is morality, but they claim that GM also deals with topics beyond morality. Soll writes,

This approach, which suggests that morality is the central, but not the only topic, can also be found in the work of Lawrence Hatab, who writes,The nominal subject of Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals is the investigation of the origins of our moral values. While the book tenaciously pursues the topic of its title without disintegrating into a loosely related collection of aphorisms (as some of Nietzsche’s other books tend to do), it nevertheless deals with more than morality, and more than genealogy.(Soll 1994, p. 168)

All of these approaches take one thing unquestioningly, that the central topic or goal of GM is to address morality. However, as I will argue later, this is a distortion of Nietzsche’s central purpose. As I argue, the aim of the text is to understand all fundamental problems, including those of knowledge and truth, as a kind of moral prejudice informed by the ascetic ideal.[The Genealogy] aims to diagnose esteemed moral traditions as forms of life-denial, in that what is valued as ‘good’ in these systems stands opposed to the actual conditions of natural life. […] Of course, questions of ethics and politics are at the core of the Genealogy, but it should be recognized that its critique of ‘morality’ is also a gateway to larger questions of knowledge, truth, and meaning.(Hatab 2008, pp. 1–3)

Distinct from the traditional interpretation of GM, the “postmodern” interpreters take knowledge, truth, and meaning to be the central and most vexing topic in GM. While they applaud his critique of the ascetic ideal and overestimation of truth, these interpretations tend to be critical about Nietzsche’s replacement or counter-ideal. The interpretations covered here include those of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Jürgen Habermas, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and Gilles Deleuze.

For Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Nietzsche’s central contribution is the observation that the notion of an objective order of nature proposed by the Enlightenment was simply a kind of superstitious prejudice and myth (Adorno and Horkheimer 2002, p. 78). However, the death of God, and therefore truth, undermines Nietzsche’s attempt to rebuild after his critique because knowledge is no longer possible. They write, “The denial of God contains an irresolvable contradiction; it negates knowledge itself.” (Adorno and Horkheimer 2002, p. 90). They then accuse Nietzsche of falling back into the ascetic ideal by using the Overman and self-overcoming as a replacement for God. The laws of truth and enlightenment values are simply replaced with self-legislation and autonomous principles similar to Kant. Nietzsche, therefore, does not escape the contradiction that knowledge and truth are no longer possible.

For Habermas, Nietzsche’s argument in GM undermines the notion of truth. Since truth is undermined, validity and contradiction lose their meaning.4 Once Nietzsche’s critical position against truth is established, the tools used to reach that point become impotent. Habermas then claims that Nietzsche is forced to retreat into aesthetic taste and mythology to justify the affirmation of older aristocratic values (Habermas 2006, pp. 226–27). Habermas seems to claim that Nietzsche simply wants to regress to ancient Greek values and Habermas finds this unacceptable.

Foucault argues that reading GM correctly means seeing that the will to truth is unhealthy, undermines itself, and destroys the subject. He writes,

For Foucault, GM demonstrates that truths are historical and forged as weapons functioning to particular ends of power. Many of Foucault’s works during his genealogical period can be seen as applied case studies using Nietzsche’s method.The historical analysis of this rancorous will to knowledge reveals that all knowledge rests upon injustice (that there is no right, not even in the act of knowing, to truth or a foundation to truth) and that the instinct for knowledge is malicious (something murderous, opposed to the happiness of all mankind).(Foucault 1977, p. 163)

Derrida’s position on Nietzsche is particularly complex, however in some sense he sees his work as an attempt to “repeat the genealogy of morals.”5 As Gary Shapiro states, “Of Grammatology repeats or translates The Genealogy of Morals, then, not by proposing a new science […] but by reconsidering the project of several putative sciences which are shown to be impossible.” (Shapiro 1990, p. 51). Derrida therefore repeats or mimics Nietzsche’s negative project in GM, but he criticizes Nietzsche for going further. He writes,

Derrida’s point is that after Nietzsche has questioned and demolished metaphysics, he seeks to found an anti-metaphysics; however, the attempt to overcome, transgress, or step beyond metaphysics always requires borrowing from metaphysics itself. As the saying goes, the gravediggers of metaphysics always end up burying themselves too.Nietzsche has written what he has written. He has written that writing-and first of all his own-is not originarily subordinate to the logos and to truth. And that this subordination has come into being during an epoch whose meaning we must deconstruct. Now in this direction (but only in this direction, for read otherwise, the Nietzschean demolition remains dogmatic and, like all reversals, a captive of that metaphysical edifice which it professes to overthrow. On that point and in that order of reading, the conclusions of Heidegger and Fink are irrefutable) […](Derrida 1998, p. 19)

In Deleuze’s account of GM, Nietzsche is not concerned with criticizing false claims to truth, but rather Nietzsche is concerned with critiquing the value of truth in itself. This critique demonstrates that the will to truth is beholden to the ascetic ideal. However, after the ascetic ideal has been “Flushed out, unmasked” we find another problem (Deleuze 1983, p. 99). If the ascetic ideal has been the only ideal hitherto, then our first candidates for a replacement, a counter-ideal, are likely to simply be other manifestations of the ascetic ideal (science for example). We must therefore prevent the ascetic ideal from covertly “replacing itself by other ideals which continue it in other forms.” (Deleuze 1983, p. 99). Deleuze then points out that we do not need a replacement of the ascetic ideal but something completely different. He writes,

This different will, he suggests, must be a kind of thinking that “ceases to be a ratio.” (Deleuze 1983, p. 101). Deleuze’s solution is to replace the ascetic ideal and the will to truth with the artist and an aesthetics of creation. His evidence comes from Nietzsche’s claim that, “Art […] is much more fundamentally opposed to the ascetic ideal than is science” (GM III 25). Deleuze writes,But we do not replace the ascetic ideal, we let nothing of the place itself remain, we want to destroy the place, we want another ideal in another place, another way of knowing, another concept of truth, that is to say a truth which is not presupposed in a will to truth but which presupposes a completely different will.(Deleuze 1983, p. 99)

For Deleuze, it is art and a will to deception that replaces the ascetic ideal. This creates a fundamentally new context where what is true is no longer God or the thing-in-itself, but the artistic celebration of appearance and life.Art is the highest power of falsehood, it magnifies the ‘world as error’, it sanctifies the lie; the will to deception is turned into a superior ideal. […] for the artists, appearance no longer means the negation of the real in this world but this kind of selection, correction, redoubling and affirmation. Then truth perhaps takes on a new sense. Truth is appearance.(Deleuze 1983, pp. 102–3)

All of these interpretations represent different approaches to what Schacht refers to as the postmodern interpretation, because there is a strong focus on the challenge to the priority of truth in GM.

A relatively new interpretation that does not come from the postmodern school but focuses on the priority of truth in GM is the work of Ken Gemes. I argue that a genetic analysis of the development of the preface adds auxiliary evidence to defend Gemes’ interpretation that the structure of GM is intentionally misleading. The central topic of GM, according to Gemes, is criticism of our commitment to the truth and the will to truth. However, Gemes does not explicate what counter-ideal could replace the ascetic ideal. David Allison and a number of other scholars, on the other hand, do provide one possible counter-ideal: eternal recurrence. My genetic reading of the preface provides auxiliary evidence for the claim that eternal recurrence composes part of the counter-ideal.

Putting this all together, I propose that a genetic analysis provides evidence for the following conclusions: (a) GM is not simply a work on morality; (b) GM intentionally misleads the reader; (c) Nietzsche’s account in Ecce Homo is supported by the evidence surrounding the genesis of the work; (d) these observations all support my interpretation that fuses the traditional and postmodern reading (that the aim of GM is not only morality but to see the priority of truth as moral prejudice); and (e) the counter-ideal Nietzsche implies is connected to eternal recurrence and Amor Fati.

Scholars such as Gemes who argue that GM intentionally misleads readers rely heavily on Nietzsche’s testimony about GM in EH. However, depending solely on Nietzsche’s interpretation of his own work in EH is philologically imprudent. An author’s testimony about their own work should not be taken at face value. Nietzsche’s relationship with his audience is complicated, because not only does he mislead and manipulate his readers in his main works, but he also manipulates scholars through his own commentary. As my recently published archival analysis demonstrates, Nietzsche intentionally misquotes and distorts his own publishing history in Ecce Homo (Parkhurst forthcoming, pp. 75–93). Ecce Homo, therefore, cannot function as a Rosetta stone for interpreting Nietzsche’s works or the history of his publication process in isolation. Rather, claims made in Ecce Homo require auxiliary evidence to support their accuracy.

Ken Gemes suggests, “Nietzsche’s initial assertion in the preface of GM that his aim is to expose the historical origins of our morality is intentionally misleading and that Nietzsche employs uncanny displacements and subterfuges in order to disguise his real target.” (Gemes 2006, p. 191). We see part of that disguise, I argue, by understanding the development of the text from notes to final publication. Nietzsche added and then removed a section from the preface that gives away his real target. Nietzsche’s claim, as we learn in the third essay, is not that we enlightened moderns have overcome morality with a move from the religious to the secular. Rather, the detachment, disinterestedness, and objectivity that characterize the scientific viewpoint itself is the ultimate embodiment of the ascetic ideal, the will to truth. Every single philosophical concept thus far, even epistemology, has been in the service of morality and the ascetic ideal. The section that was added, and then removed, from the preface gives away the ending and thus would have ruined the disguise.6

I understand the structure of GM as a sort of hermeneutic spiral that begins with the morality of actions but then looks for the root cause. The first essay, on the origin of good and evil and ressentiment, is the first turn of the spiral. Then, the second essay represents the second turn of the hermeneutic spiral, which drills down one level deeper into the origin of conscience. The third essay represents the real target of GM and the final turn of the hermeneutic spiral. At the deepest level, the critique in GM is aimed at the ascetic ideal and reveals that all of our thinking, from secular science to our basic epistemological problems, are thoroughly mired in ascetic moral values. At the end of the third essay of GM, the reader finds the target at which Nietzsche was aiming at was not morality, as a subset of human concerns, but rather at the foundational enterprise of the West itself. Both science and the ascetic ideal stand on the same ground, because they contain the same overestimation of truth (Nietzsche 1967b, GM III 25). Nietzsche then goes on to argue that the will to truth is not a remnant of the ascetic ideal but its core (Nietzsche 1967b, GM II 27). The will to truth, the will to privilege truth over falsity, is a value-laden moral judgment. The secular and scientific views we have developed are not a counter-ideal to moral prejudice. Everything, down to our last epistemological presupposition, fundamentally is a kind of value-laden position. This is precisely the ending Nietzsche gives away in the section he added, and then removed, from the preface.

3. Genetic Analysis of the Preface

The texts used in this analysis are found in Nietzsche’s personal library, stored in the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek [HAAB], as well as in his broader archived estate, stored in the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv [GSA].

The publication process in 19th-century Germany was a complex one, and given the rapidly changing standards during that time, any statement about it is bound to overgeneralize. However, with regard to the publication of Nietzsche’s texts, we can begin by analyzing a seven-step publishing process from preliminary drafts all the way through to late editions. Genetically speaking, I order the textual evidence along the following general categories of development:

- Preliminary stages/Drafts [Vorstufe]

- Handwritten fair copy [Reinschrift]

- Print manuscript [Druckmanuskript]

- Correction pages [Korrekturbogen & Korrekturbogenexemplar]

- Author’s examination copy [Handexemplar]

- First edition [Erstdruck]

- Later developments (if any)

This analysis has made sure to track drafts, a handwritten fair copy that became the print manuscript [D-20a], a correction copy [HAAB 4616], and several letters sent between Nietzsche and his publisher. These changes offer important insight into the scope of the project offered in Nietzsche’s The Genealogy of Morals.

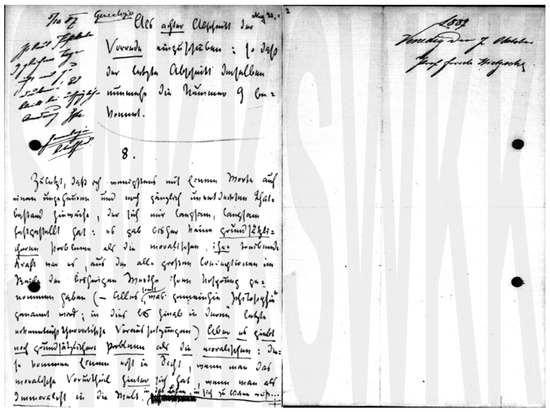

The first edition of GM, published in 1887 by C. G. Naumann, contains a preface with eight sections, the last of which is dated July 1887. The text itself was printed and sent to Nietzsche’s friends at the latest in November of 1887 and was later available to the public.7 Unlike some of Nietzsche’s other prefaces that were written at one time, the sections of the preface were pulled from drafts in different notebooks, and through the publication process the structure of the preface changed considerably.

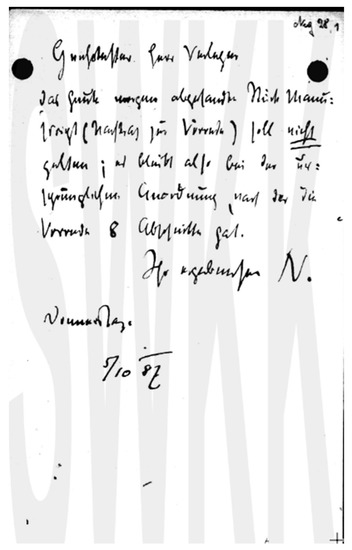

The preface of GM was to originally consists of seven sections, then eight, then nine, and finally went back to eight again for the first edition. This article focuses on the section that was added and then removed. The section was to be added between Section 7 and 8. The section that was previously labeled 8 was moved to Section 9. Nietzsche sent this additional section to his publisher on the morning of 5 October 1887; this is months after the July date on the final section of the preface in the first edition. This addition is, therefore, quite late. However, on the very same day, but later in the afternoon, Nietzsche sent another letter to his publisher telling him not to insert this section. This section was added and then almost immediately retracted. I argue that this section was retracted, not because Nietzsche disagreed with it, but because it gives away the framework for the book itself. I will discuss this added section shortly.

3.1. A Genetic Analysis

One of the first things one will notice about the preface is how wide its sources are in the notebooks. The preface can be found in KSA 5 247–256. However, when we look at the preparatory drafts, they are not taken from one notebook but rather an unexpectedly large number of different notebooks. These variants are from at least five separate notebooks, including: N VII 1, N VII 2, W I 1, W I 8, and W I 5. Unlike other pieces of Nietzsche’s published work, the preface is a kind of bricolage that is cobbled together from a number of notebook entries and drafts.

3.2. Handwritten Fair Copy

We know there was an original fair copy that was a very short piece, what Nietzsche calls a “small polemic”, on 17 July 1887.8 This contained some of the ideas for the first essay of GM that Nietzsche claims are a direct development of Beyond Good and Evil. He asks in that letter to go straight to print and repeats this in another letter on 18 July 1887.9 However, as the project grew, Nietzsche telegraphed Naumann (his publisher) on 20 July 1887 and asked for the manuscript back, stating, “Due to unforeseen circumstances, please return the manuscript.”10 The current location or existence of this manuscript is unknown. However, it is clear there was a fair copy that was made and sent to the publisher, but then requested back.

3.3. Print Manuscript

There are fair copies that became the two surviving print manuscripts for GM stored in the Goethe and Schiller Archive. The first one contains the Title page and Preface, as well as Essay I and II and can be found in the Goethe and Schiller Archive under reference number GSA 71/27.1. Of interest is that this document demonstrates a very unsettled preface. It becomes apparent when one examines page VI of the print manuscript that originally the preface was to have seven sections and then end there; it even contains the dated inscription and then the beginning title of the first essay. However, when one looks at page VII, one finds another kind of paper and ink with the eighth section of the Preface, where it ends in the published work.11 The paper then changes again to begin the first section of Essay I. What this shows is that the print manuscript itself was considerably changing, and this includes the sections of the Preface as it was eventually published in the first edition. The Preface was not simply written out section-by-section in one notebook, transferred to a fair copy print manuscript, and printed. It was in a state of flux until it was printed.

3.4. Correction Pages

The correction pages for The Genealogy of Morals are stored in Nietzsche’s personal library at the HAAB. The manuscript bore the reference number E40 at one point, but now its shelfmark is HAAB C 4616.14 The corrections are by both Nietzsche and Johann Heinrich Köselitz (also known as Peter Gast). However, the correction pages do not contain the Preface, but start out with Section 1 of the main text on the 9th sheet of the document.15

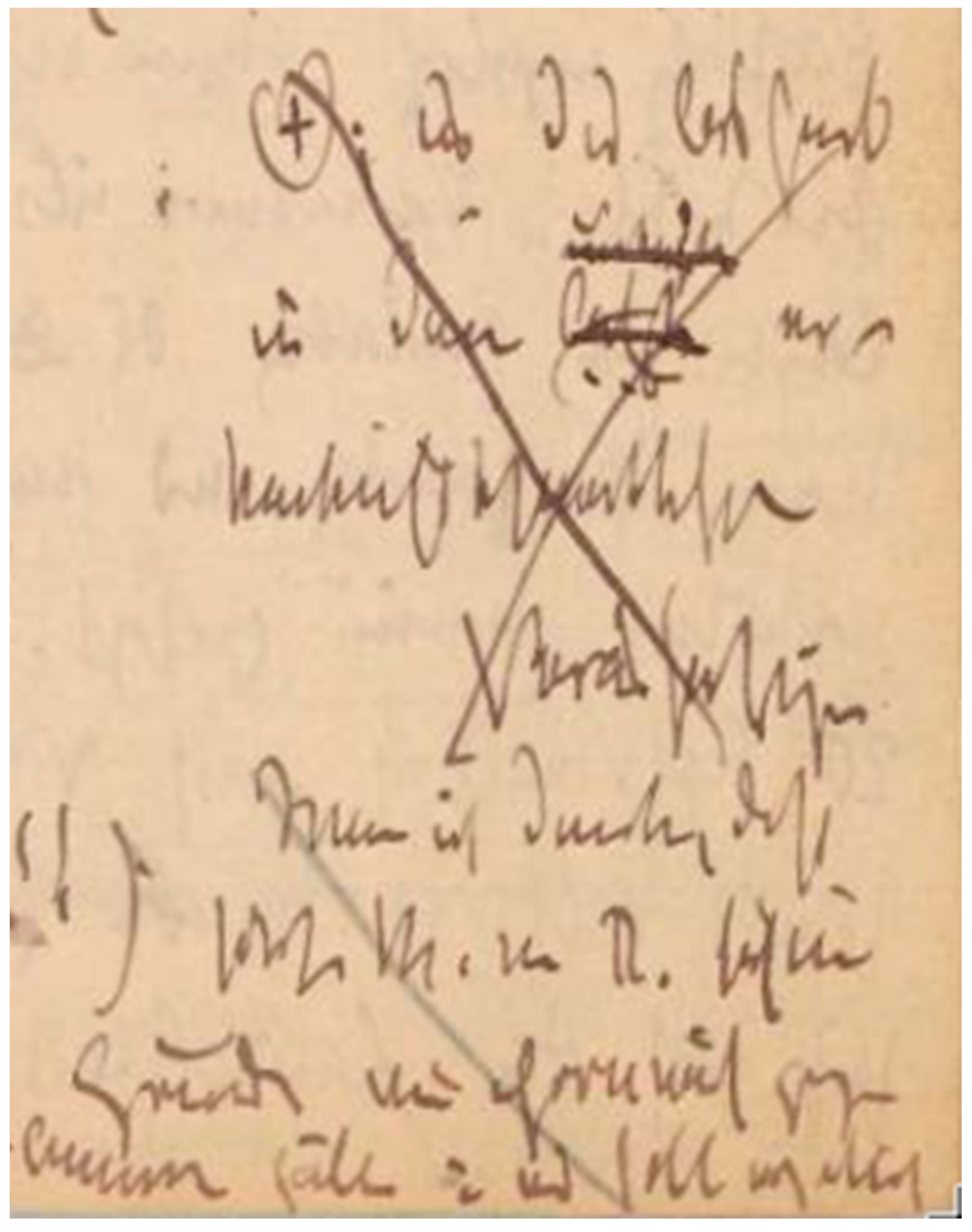

3.5. The Letter

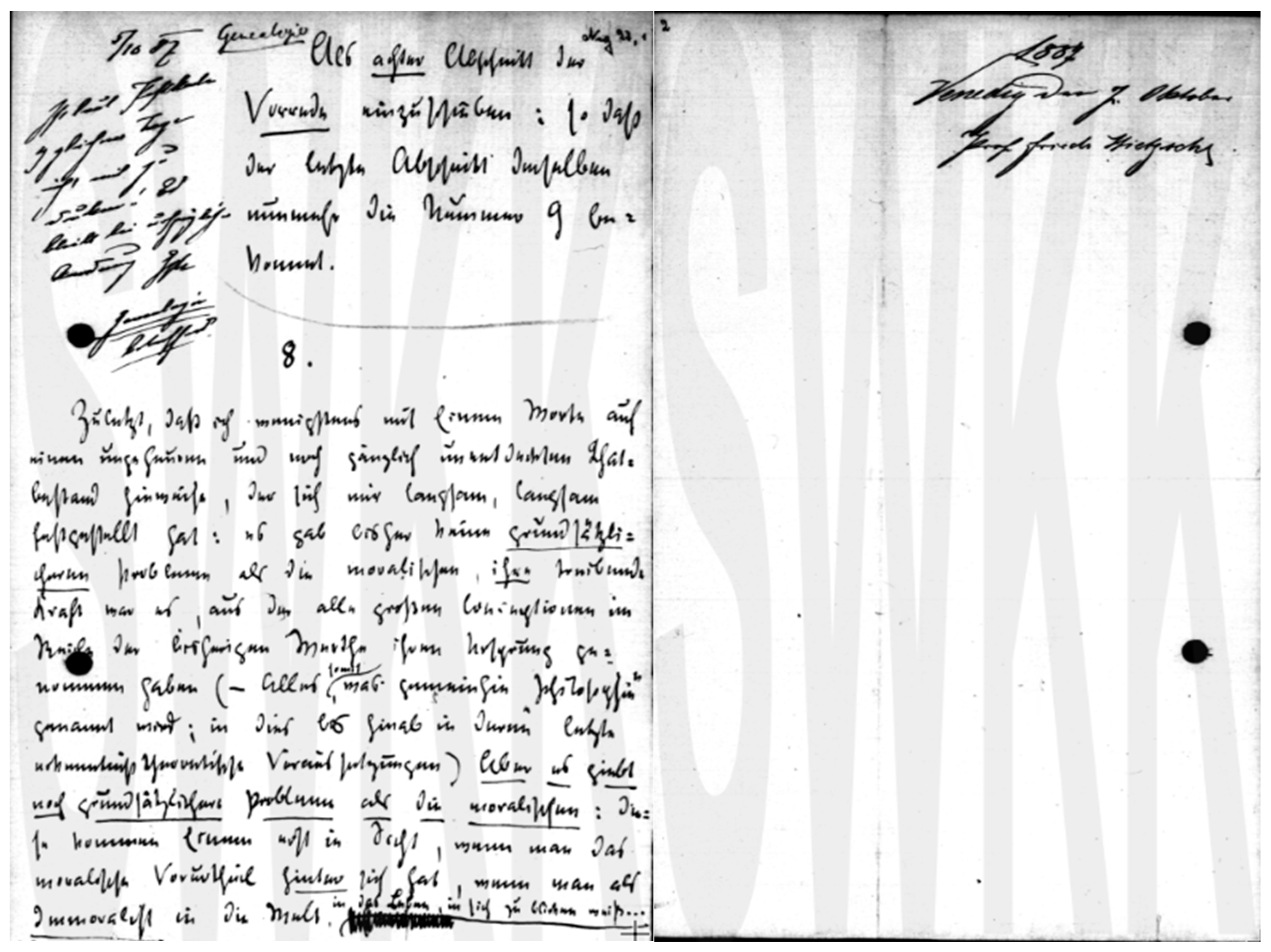

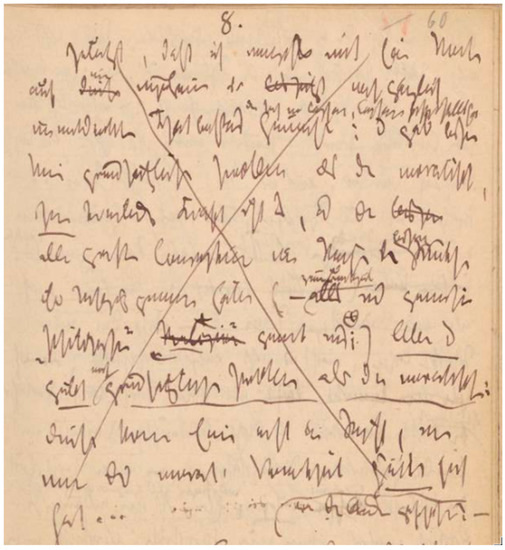

On 5 October 1887, Nietzsche sent a letter to his publisher (see Figure 1). In the letter, Nietzsche asked Naumann (his publisher) to insert a section between the last two sections of the preface in GM.16 That is, the new section was to be the 8th section and what was previously the 8th section was to become the 9th section.17

Figure 1.

922. Nietzsche, Friedrich an Naumann, Constantin Georg (Leipzig/Constantin Georg Naumann, Buch- und Steindruckerei) [5 October 1887]. GSA 71/BW 291, 1 Bl 33.

This added section argues that up until now, all problems of philosophy have been moral ones. Even the problems of epistemology are moral problems. “Philosophy” (including logic, epistemology, and metaphysics) has moral judgments at its foundation. That is, Nietzsche is telling his reader not to expect an ethical treatise, like that of Kant or Mill, but rather a critique of all fundamental problems up to now. Nietzsche then points to a new ideal beyond morality.

The added section in the preface demonstrates that Nietzsche understood this to be his project. He sees his project as clearing away “philosophy” as such, because all “fundamental problems” and “great conceptions”, including the most basic “Epistemological Presuppositions”, are moral.

However, what is particularly interesting is how Nietzsche suggests that even here, with the prejudice of morality and philosophy behind us, our job is not yet done. In particular, he argues that there are yet more fundamental problems than just moral ones. This section within the letter that is to be inserted within the preface reads:

8.

Translated this reads:Zuletzt, daß ich wenigstens mit Einem Worte auf einen ungeheuren und noch gänzlich unentdeckten Thatbestand hinweise, der sich mir langsam, langsam festgestellt hat: es gab bisher keine grundsätzlicheren Probleme als die moralischen, ihre treibende Kraft war es, aus der alle großen Conceptionen im Reiche der bisherigen Werthe ihren Ursprung genommen haben (—Alles somit, was gemeinhin „Philosophie“ genannt wird; und dies bis hinab in deren letzte erkenntnißtheoretische Voraussetzungen) Aber es giebt noch grundsätzlichere Probleme als die moralischen: diese kommen Einem erst in Sicht, wenn man das moralische Vorurtheil hinter sich hat, wenn man als Immoralist in die Welt, in das Leben, in sich zu blicken weiß…

Finally, I would like to point out, at least in one word, a tremendous and still completely undiscovered fact, which has gradually become apparent to me: up till now there have been no more fundamental problems than the moral [ones], it was their driving force from which all the great conceptions in the realm of the previous values have originated (—Consequently everything, that is commonly called “philosophy”; and this down to the last epistemological presuppositions) But there are even more fundamental problems than the moral [ones]: these come into view only when you have moral prejudice behind you, when you know how to look into the world, into life, into yourself as an Immoralist…18

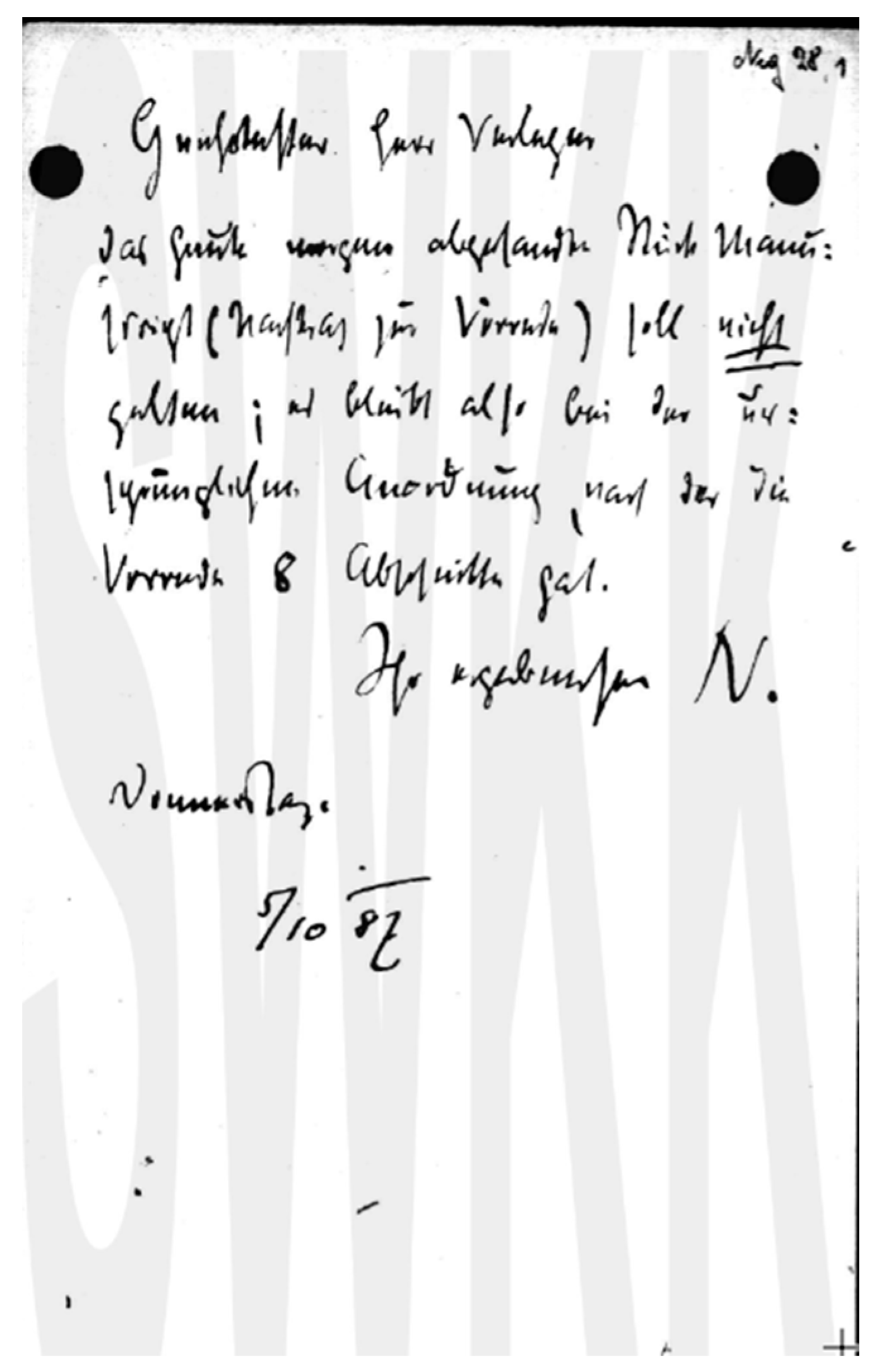

However, that same day, Nietzsche sent the following retraction (see Figure 2), asking that the section not be included in the preface.19

Figure 2.

923. Nietzsche, Friedrich an Naumann, Constantin Georg (Leipzig/Constantin Georg Naumann, Buch- und Steindruckerei) [5 October 1887]. GSA 71/BW 291, 1 Bl 34.

What exactly are we to make of such an addition and retraction? One might imagine that Nietzsche wrote that section in the first letter in the moment he was writing. If so, that would give us good scholarly justification to ignore such a piece of writing. Perhaps it was just a momentary thought that Nietzsche had and without much thought or serious consideration sent off to be published. One might argue that this impromptu letter should be disregarded since the letter was retracted the same day it was sent. This might give the impression that it was not a considered view and therefore not a view we should take into consideration when reading Nietzsche’s philosophy.

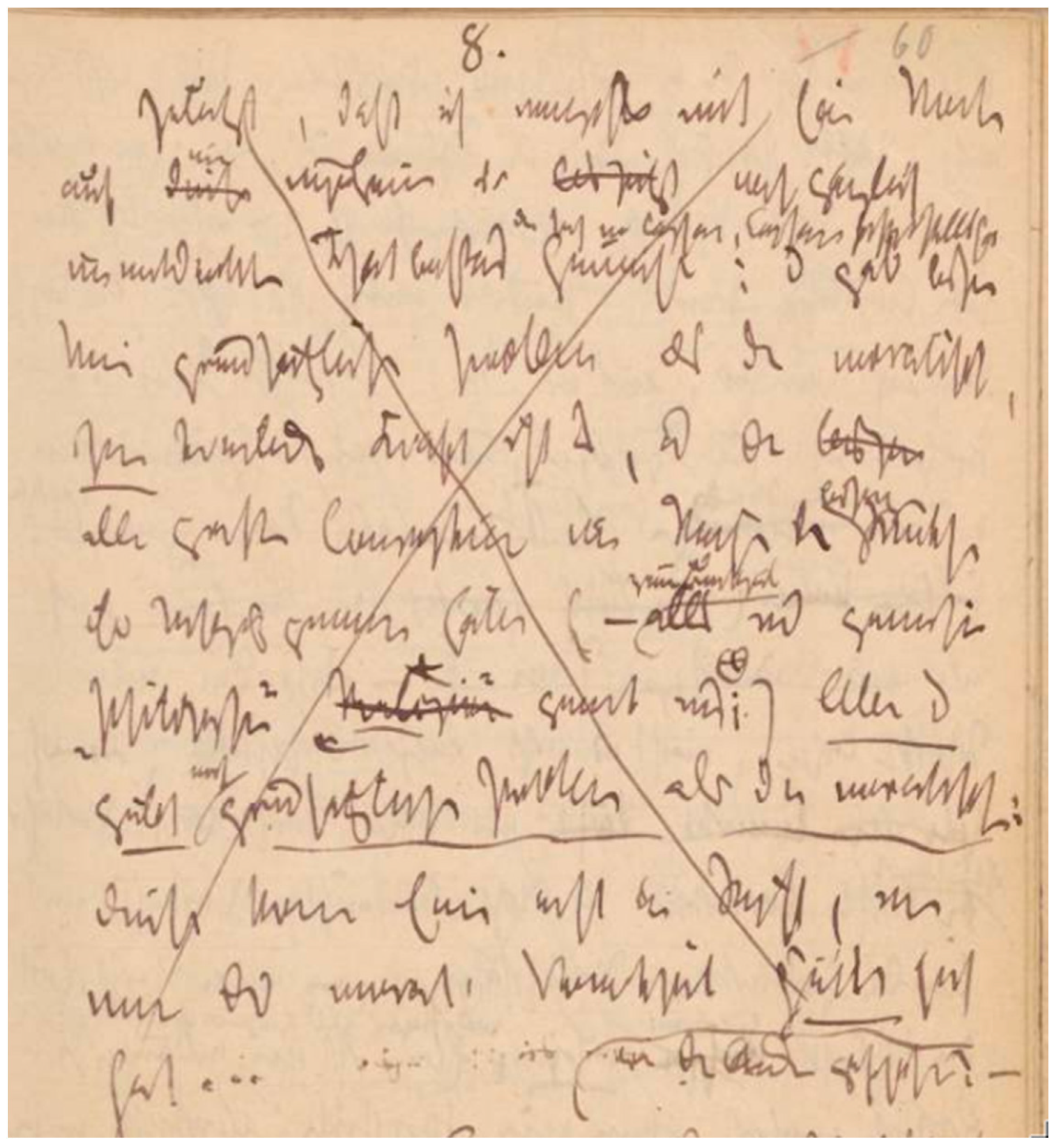

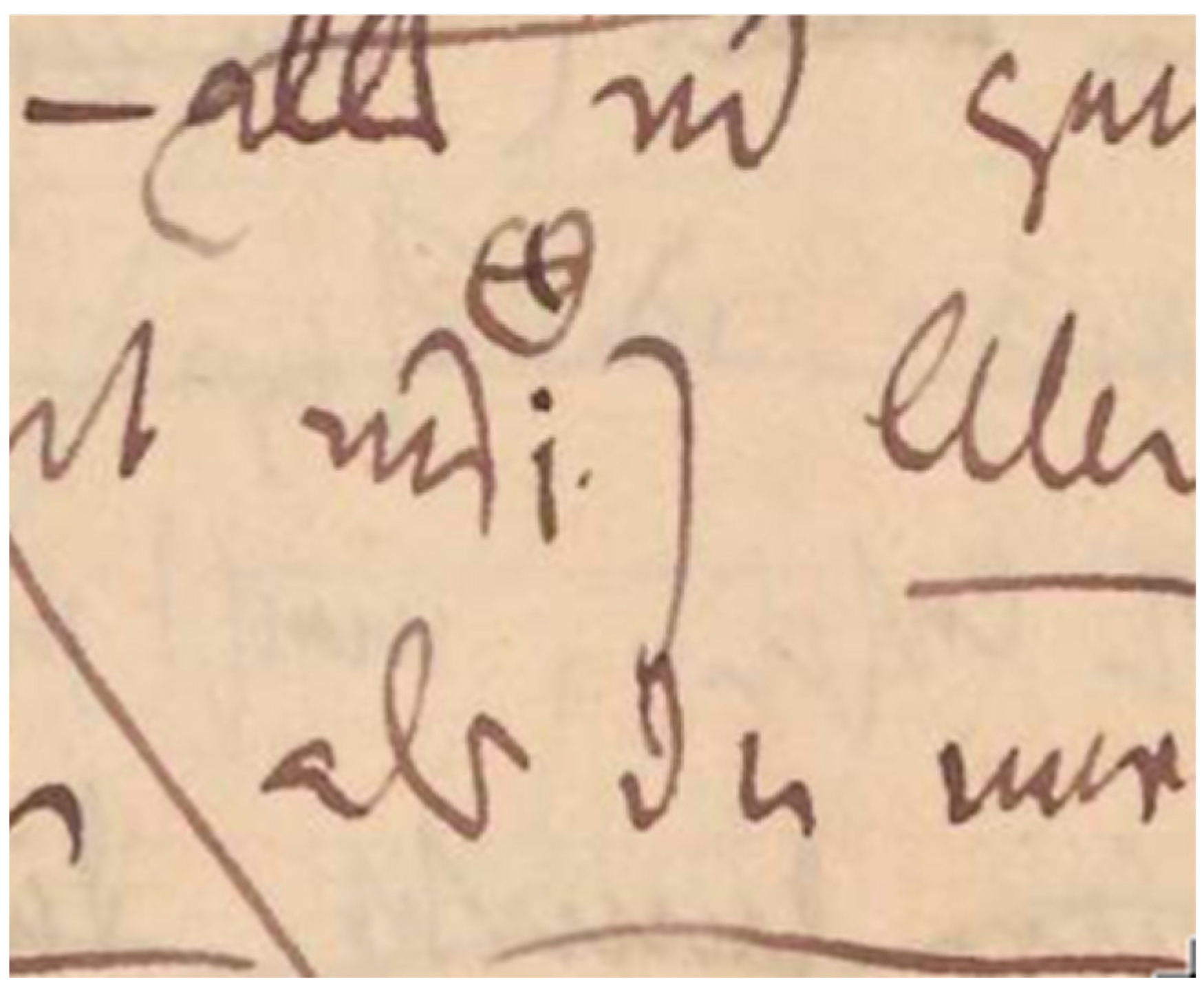

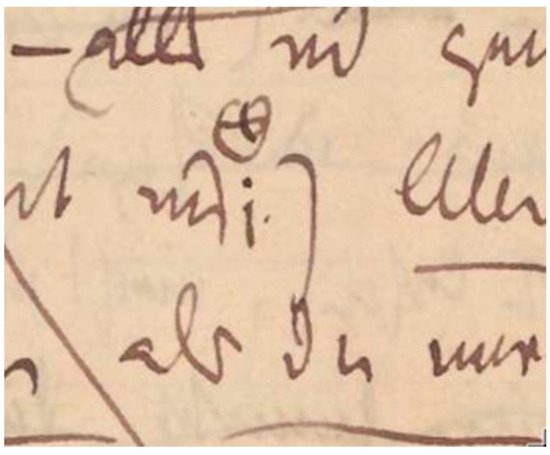

However, while this account is plausible, this proves not to be the case. The section in the letter does not originate in that first letter but in a notebook entry not mentioned in the KSA. That is, Nietzsche wrote the section out previously and actually copied it from his notebook into the letter. This fact is completely absent in the KSA. The first draft of the section can be found in Notebook N VII 3 on page 60 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

KSA 12, 5[80], pg. 220. KGW VII 1, 5[80], 224. Mette: N-VII-3 (http://www.nietzschesource.org/DFGA/N-VII-3,59et60, accessed on 4 April 2022).

The text of this notebook fragment has been transcribed as follows:

8.

Translated this reads:Zuletzt, daß ich wenigstens mit Einem Worte auf einen ungeheuren und noch gänzlich unentdeckten Thatbestand hinweise, der sich nur langsam, langsam festgestellt hat: es gab bisher keine grundsätzlicheren Probleme als die moralischen, ihre treibende Kraft ist es, aus der alle großen Conceptionen im Reiche der bisherigen Werthe ihren Ursprung genommen haben (—zum Beispiel alles was gemeinhin “Philosophie” genannt wird; und dies bis hinab in deren letzte erkenntnißtheoretische Voraussetzungen). Aber es giebt noch grundsätzlichere Probleme als die moralischen: diese kommen Einem erst in Sicht, wenn man das moral<ische> Vorurtheil hinter20 sich hat…21

Finally, I want to point out, at least with one word, an immense and still completely undiscovered fact, which has only been slowly, slowly established: there have been no more fundamental problems than the moral ones, it is their driving force from which all great conceptions in the realm of the previous values have originated (—for example, everything that is commonly called “philosophy”; and this right down to its final epistemological presuppositions). But there are even more fundamental problems than the moral ones: these only come into sight when one has moral prejudice behind them…

We can, therefore, trace the final draft in the letter sent to the publisher in 1887 back to this draft in his notebooks from around 1886.

The changes from the draft to the letter show that Nietzsche clearly thought about and edited this section for publication. Three minor changes and one major addition are important. Further, we will then examine the revealing edits to this notebook entry that are not transcribed in the KSA.

First, we see Nietzsche change “nur” to “mir”. This switches from the passive to the possessive. Instead of it being a fact that became “slowly established ”, Nietzsche takes ownership of this development, and it is “gradually become apparent to me”. Nietzsche is, therefore, taking possession of this realization.

The second change is from present tense to past tense. In the original draft, it reads “ihre treibende Kraft ist es” (“it is their driving force”), but in the letter the “ist” is switched out for “war”, so it reads “ihre treibende Kraft war es” (“it was their driving force”). This change indicates that in original draft when Nietzsche is talking about the driving force of “all great conceptions”, it indicates this is present, applying to all. However, when this switches to past tense in the letter, it hints at problems other than moral ones in the future. That is, this makes the sentence conform to the previous part of the statement “up till now”, making it a clear statement about the past but leaving the future open.

The third change from the draft to the letter is a change from “zum Beispiel alles” to “Alles somit”. This changes it from “for example everything” to “consequently everything.” This changes the logical connection between what comes before the parenthesis and what comes after the parenthesis. In the original draft, philosophy is one example among others. However, as is clearer in the letter, all philosophical problems (including epistemological problems) are moral problems.

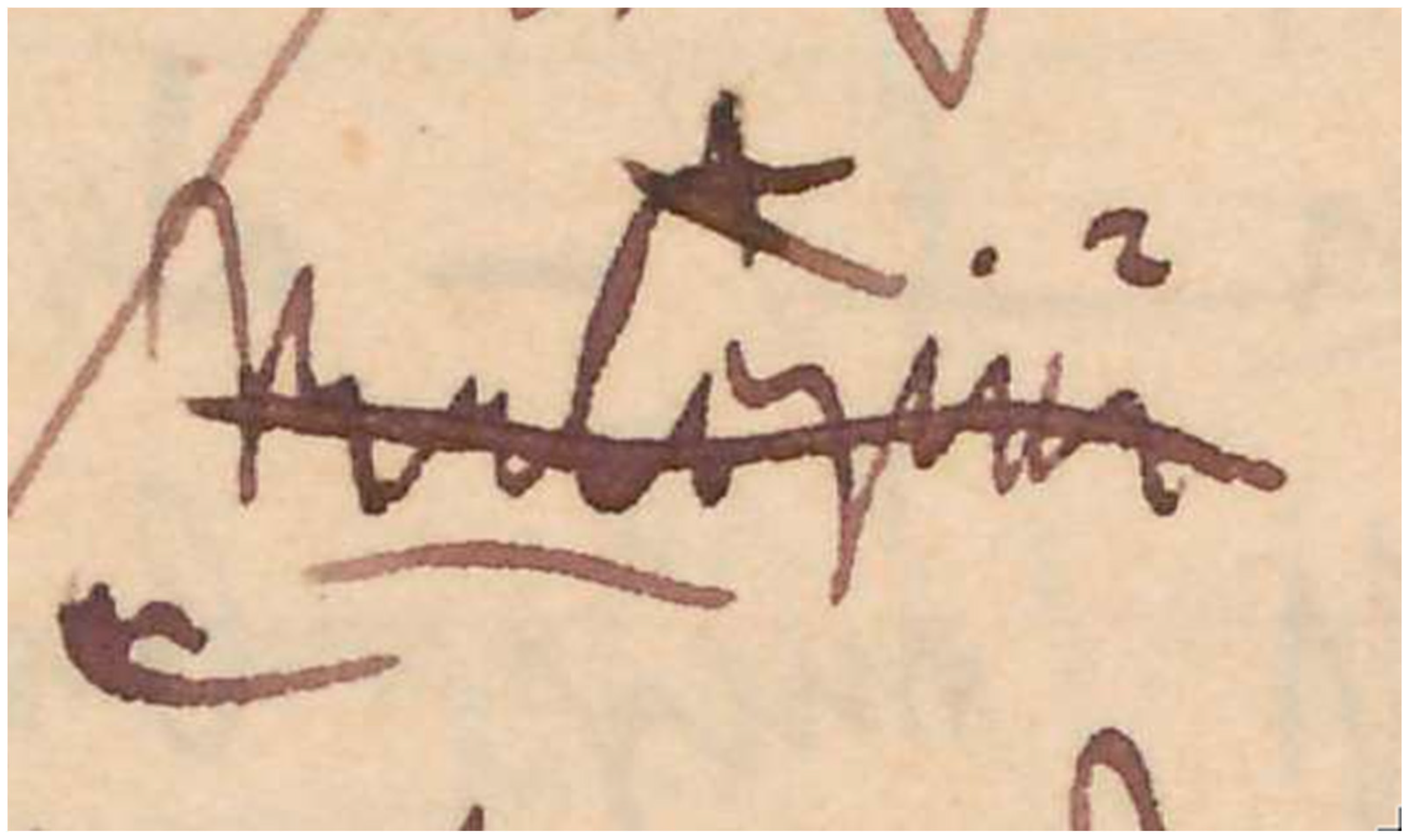

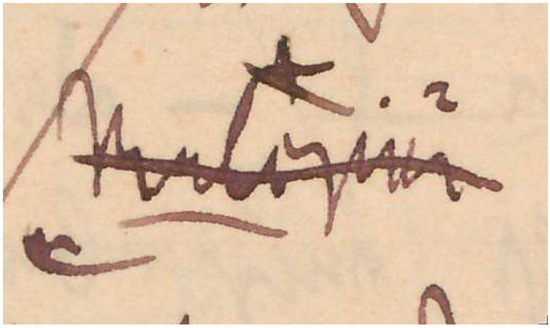

Not only does the development from the draft to the letter show the changes and thought Nietzsche put into this section, but the changes in the draft itself are also important. The connection between the second and third changes becomes clearer when you move beyond the KSA and look at Nietzsche’s notebook itself. That is, when we look at the notebook itself, it contains edits not clearly indicated in the KSA.22 In the original, one can see that “for example” [“zum Beispiel alles”] originally made more sense as there were multiple examples. It not only included philosophy, but also “religion” (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

KSA 12, 5[80], pg. 220. KGW VII 1, 5[80], 224. Mette: N-VII-3 (http://www.nietzschesource.org/DFGA/N-VII-3,59et60, accessed on 4 April 2022).

Therefore, in the original draft, philosophical problems were simply one example among others that were moral. In the letter, however, it is clear that if all fundamental problems hitherto have been moral, then all fundamental problems in philosophy hitherto have also been moral ones. This makes the logic of the relationship much clearer.

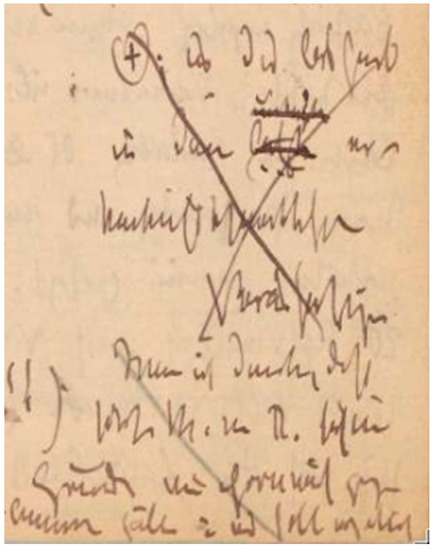

Finally, the alterations to the draft in another case are also revealing when contrasted with the letter. When we look at the draft, we see that a whole subsection was inserted. You can see the main text with the (+) sign, and then the insert down below with another (+) sign indicating the piece of text to be inserted (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

KSA 12, 5[80], pg. 220. KGW VII 1, 5[80], 224. Mette: N-VII-3 (http://www.nietzschesource.org/DFGA/N-VII-3,59et60, accessed on 4 April 2022).

Figure 6.

(The insertion). KSA 12, 5[80], pg. 220. KGW VII 1, 5[80], 224. Mette: N-VII-3 (http://www.nietzschesource.org/DFGA/N-VII-3,59et60, accessed on 4 April 2022).

In the KGW IX, 3, this addition was confirmed.23 Notably, the line that clarifies the whole section was added, “und dies bis hinab in deren letzte24 erkenntnißtheoretische Voraussetzungen.” [“and this down to the last epistemological presuppositions”].

The final and most dramatic change from the draft in the notebooks to the letter is the addition of the following line: “when you know how to look into the world, into life, into yourself as an Immoralist…” This line, I argue, suggests and points to a counter-ideal to the ascetic ideal: eternal recurrence and Amor Fati.

Many of these changes are minor, but what this shows is that Nietzsche spent considerable time thinking about and editing this section over a period between 1886 and 1887; it was not simply a jotted down botched idea he had decided to retract. Rather, it gives away the conclusion to the work, and thus would have ruined Nietzsche’s plan to mislead his readers.

4. Conclusions: An Immoral Counter-Ideal

What we discover at the end of the third essay of GM is that every-day moral matters do conform to the ascetic ideal. However, all considerations extending over secular evidence, science, and our overestimation of truth also conform to the ascetic ideal. These are all forms of moral prejudice. They all conform to the same ideal and, until now, there has been no other ideal. The ascetic ideal filled the void created when man asks, “why do I suffer”, and therefore closed the door to suicidal nihilism. Man was still able to will, but it was a will to nothingness. This will to nothingness contained a hatred of the human, animal, material, sense—all appearances—and contained an essential aversion to life (GM III 27). The ascetic ideal, constrained by the will to truth, demands honesty about itself and reveals its hatred of all life. The only possible conclusion to the will to truth, the forged kernel of the ascetic ideal, is nihilism. Lawrence Hatab gives an apt three-part definition of nihilism that accurately describes the tacit conclusions of the ascetic ideal revealed through Nietzsche’s critique. Hatab writes that nihilism claims, “The world itself possesses no value, human existence is ultimately meaningless, and knowledge claims are without foundation.” (Hatab 1987, pp. 91–111).

While traditionally the following sentence in GM III 27 has been rhetorically read, that is, it has been read as not really asking a question, I believe it is a very serious question. Nietzsche writes, “And here I again touch on my problem, on our problem, my unknown friends (for as yet I know of no friend): what meaning would our whole being possess if it were not this, that in us the will to truth becomes conscious of itself as a problem?” (Nietzsche 1967b, GM III 27). If the will to truth gains self-consciousness, the conclusion is that morality, which includes all the most fundamental thoughts of human beings up to the present, “will gradually perish now.” (Nietzsche 1967b, GM III 27). If morality and the ascetic ideal perish, we are left in a void, because as Nietzsche states, “Apart from the ascetic ideal, man, the human animal, had no meaning so far.” (Nietzsche 1967b, GM III 28). Without the ascetic ideal, not only are morality and epistemology unfounded, but the foundation of all meaning hitherto has been taken away. If we take Nietzsche to be asking a genuine question, we can ask along with him, “what meaning would our whole being have if it was not this?” It is, then, not a rhetorical, but an open question. It is an invitation to his friends, friends whom he does not know yet. He is inviting these friends, who are immoralists and free spirits of future generations, to consider an opposite ideal to the ascetic ideal.

What exactly that counter-ideal might be, Nietzsche left somewhat vague and debatable. Scholars have put forward various possible counter-ideals. Maudemarie Clark considers the will to power to be the counter-ideal (Clark 1990, p. 242). Other scholars such as Julie Anne Buchsbaum and Deleuze consider art as a counter-ideal. 25 Simon May considers “To be what one is” as a favorable replacement (May 1999, p. 104). Others such as John Richardson and Franz zu Solms-Laubach have considered the Overman to be a counter-ideal (Richardson 2020, p. 480; Solms-Lubach 2007, p. 229). Paul Franco has suggested that the free spirit is Nietzsche’s counter-ideal (Franco 2011, p. 203). Alternatively, Gudrun von Tevenar considers a variety of qualities exhibited in the character of Zarathustra to be pivotal aspects of Nietzsche’s counter-ideal, including love, superabundance, and eternity (not eternal recurrence) (von Tevenar 2016, pp. 285–95). A growing number of scholars, including David Allison, Bevis McNiel, Brian Leiter, Sharli Anne Paphitis, Peter Poellner, Paul Loeb, and others have claimed that in some way or another, eternal recurrence functions as the counter-ideal to the ascetic ideal (Allison 2001, pp. 245–46; McNiel 2021, p. 19; Leiter 2002, pp. 287–88; Paphitis 2009, p. 195; Poellner 2009, p. 297; Loeb 2005, p. 93n4).

Nevertheless, there is an emerging scholarly consensus that eternal recurrence represents a counter-ideal. This is primarily based on several pieces of evidence stemming from EH, GM, and Z that I will now articulate and subsequently add a new piece.

As mentioned previously, in EH, Nietzsche states that “A counterideal was lacking—until Zarathustra.” (EH GM). Further evidence pointing to Thus Spoke Zarathustra comes from GM itself. While Nietzsche asks the question, “where is the opposing will expressing the opposing ideal?”, he provides many negative answers in Essay III, but no positive answers (GM III 25). However, at the end of Essay II, Nietzsche suggests that an attempt at the reverse of all ideals hitherto, the ascetic ideal, is possible, but he asks, “To whom should we turn today with such hopes and demands?” (GM II 24). In the next section, Nietzsche claims he must be silent, and then refers the reader to Thus Spoke Zarathustra (GM III 25).

The idea that the counter-ideal is contained in Z is generally accepted on the above evidence. However, there are three more pieces of evidence that point to eternal recurrence.

First, throughout Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the main character confronts the thought of eternal recurrence multiple times and fails to fully confront his “most abysmal thought” head-on. It is not until the penultimate section of book III, “The Convalescent”, that Zarathustra is able to overcome his nausea and come to terms with the idea of eternal recurrence. The overall structure of the book, which culminates in the confrontation with the thought of eternal recurrence, makes eternal recurrence a natural candidate to consider for the counter-ideal.

A second piece of evidence is that, in GM II, when describing where we should find the will opposing the reigning ideal, Nietzsche describes a redemption from “the great nausea.”

In the penultimate section of Z, “The Convalescent”, where Zarathustra confronts the thought of eternal recurrence, he must recover and be redeemed from his great nausea [Ekel]. This reference to being redeemed from the great nausea points to Zarathustra’s encounter with the thought of eternal recurrence.He may bring home the redemption of this reality: its redemption from the curse that the hitherto reigning ideal has laid upon it. This man of the future, who will redeem us not only from the hitherto reigning ideal but also from that which was bound to grow out of it, the great nausea [vom grossen Ekel], the will to nothingness, nihilism. (GM II 24)

However, perhaps the most straightforward argument that eternal recurrence is the core ideal of Thus Spoke Zarathustra comes from Nietzsche’s description in EH. In discussing Thus Spoke Zarathustra in EH, Nietzsche writes, “The fundamental conception of the work [Thus Spoke Zarathustra, is] the idea of eternal recurrence” (EH Z 1). If a counter-ideal of such importance did not exist before Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the topic concerning the fundamental conception of the work would be a likely candidate for the counter-ideal.

All of these pieces of evidence have previously been cited, however, the added, but then removed, section of the preface adds an additional piece of evidence connecting the counter-ideal to BGE and Amor Fati.

My argument thus far has been that Nietzsche considered all fundamental problems, including epistemology, metaphysics, and logic, to have been moral problems. This means that the ascetic ideal and will to truth are themselves a kind of moral prejudice. The key, then, is to open our eyes to an immoral ideal that lies beyond good and evil.

The section of the preface that was removed tells us that there is a counter-ideal that exists for immoralists who have put good and evil behind them. The final lines of the section read, “But there are even more fundamental problems than the moral ones: these come into view only when you have moral prejudice behind you, when you know how to look into the world, into life, into yourself as an Immoralist…” This line draws the careful reader back to the problem of being an immoralist in Beyond Good and Evil, and the question of what a counter-ideal to the ascetic ideal may look like.

Aside from Z, eternal recurrence is most clearly discussed in GS 341 and BGE 56, where Nietzsche inquires about our own reaction to this thought; he claims that it will either crush you, or lead to a previously unknown feeling: Amor Fati (Love of Fate).

Amor Fati is commonly thought to be an affirmation of life in the face of necessity. Amor Fati is therefore one kind of possible reaction to the thought of one’s life returning necessarily in the same order eternally. Amor Fati is mentioned only four times in the writing that scholars usually consider published, once in The Gay Science, twice in Ecce Homo, and once in Nietzsche Contra Wagner. In Nietzsche Contra Wagner, Nietzsche reflects on his continual sickness and suggests that everything necessary is useful in itself, and not only should one bear it, but love it; this is the attitude of Amor Fati.26 In EH, reflecting on Amor Fati, he states that what is necessary does not hurt him (Nietzsche 1967a, EH CW 4). Earlier in EH, he states the following,

However, the most straightforward account of Amor Fati begins in book four of The Gay Science in which eternal recurrence is first introduced. Nietzsche writes,My formula for greatness in a human being is Amor Fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backwards, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it […] but love it.(Nietzsche 1967a, EH Clever 10)

It is notable that not wanting to accuse is one of the important results of Zarathustra’s recovery after confrontation with eternal recurrence in “The Convalescent.” While GS provides the most straightforward account of Amor Fati, we also obtain a glimpse of it being performed in Beyond Good and Evil 56.I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful. Amor Fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation.27

In this section, Nietzsche addresses Amor Fati, but not by name, in relationship to eternal recurrence. BGE 56 states, “Whoever has really […] looked into, down into the most world-denying of all possible ways of thinking—beyond good and evil and no longer […] under the delusion of morality—may just thereby […] have opened his eyes to the opposite ideal.” (Nietzsche 1966, BGE 56). This introduction parallels the added and then removed preface section in GM that argued these new ideals and fundamental problems that come into view “when you know how to look into the world, into life, into yourself as an Immoralist…” However, BGE 56 not only tells us how these new ideals come into view, but what someone who experienced them would be like. He writes,

Someone who has opened his eyes to the opposite ideal, in the face of the idea of eternal recurrence, can affirm life through Amor Fati. Thinking through the thought of eternal recurrence might very well crush you as Nietzsche mentions in GS 341, but it might also change you into the kind of person that wants nothing more fervently than eternal necessity. If one could achieve this, one would have willed beyond good and evil and beyond morality. If everything is necessary, there is no praise or blame to be distributed. There is no linear eschatological ending or heavenly after-world to which we can flee our lives. To think through eternal recurrence and be able to will Amor Fati is to have found the counter-ideal beyond morality. This is indicated by the ending of the removed section, which gives away the ending of GM, stating, “But there are even more fundamental problems than the moral [ones]: these come into view only when you have moral prejudice behind you, when you know how to look into the world, into life, into yourself as an Immoralist…” The hope, then, is to encounter these problems through the thought of eternal recurrence and be able to will Amor Fati, the counter-ideal. The attitude of Amor Fati offers a solution to the problem of meaning without falling back into either morality or the ascetic ideal.[…] the opposite ideal: the ideal of the most high-spirited, alive, and world-affirming human being who has not only come to terms and learned to get along with whatever was and is, but who wants to have what was and is repeated into all eternity, shouting insatiably da capo [from the beginning, play it again]—not only to himself but to the whole play and spectacle, and not only to a spectacle but at bottom to him who needs precisely this spectacle—and who makes it necessary because again and again he needs himself—and makes himself necessary.(Nietzsche 1966, BGE 56)

According to Nietzsche, the fundamental questions of philosophy that have been put forward thus far are not value-free but, rather, deeply value-laden. To put this more precisely, Nietzsche is rejecting the fact–value distinction itself. Questions of morality are not separable from epistemology and questions of epistemology are not separable from morality. Thus, while GM certainly is a critique of morality (as the traditional interpretation holds) it is not merely that. It is also a genealogy of knowledge and an attack on the unquestioned intrinsic value of truth (as postmodern interpretations sometimes hold). In a sense, both traditional and postmodern interpretations are partially accurate but incomplete. As I have argued using a genetic form of argumentation that tracks the development of the text through archival evidence, both are partially correct, as Nietzsche sees all fundamental problems hitherto as moral questions in service of the ascetic ideal and the will to truth. It is only once we look beyond morality, beyond the ascetic ideal, that we have the possibility of confronting other ideals (such as Amor Fati) and even more fundamental questions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In this essay I will be using standard scholarly abbreviations: The Gay Science (GS), Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Z), Beyond Good and Evil (BGE), The Genealogy of Morals (GM), Ecce Homo (EH), and Nietzsche Contra Wagner (NCW). The KGW represents the most comprehensive of Nietzsche’s complete works (Kritische Gesamtausgabe Werke) and the KSA is a smaller version of complete works (Samtliche Werke: Kritische Studienausgabe). Similarly, Nietzsche’s letters are found in KSB (Sämtliche Briefe: Kritische Studienausgabe) or KGB (Briefe: Kritische Gesamtausgabe). |

| 2 | (Nietzsche 1887), image 4 (title page) [Princeton University Library. Call number: 6179.67.39. PT2440.N72 A6 2002 vol.15. https://dpul.princeton.edu/pudl0106/catalog/7s75dd671]. Accessed 4 April 2022. |

| 3 | While the distinction between “Traditional” and “Postmodern” is itself very crude, this has guided the debate and is therefore a historically useful, if overgeneralized, demarcation. As this distinction was created by the “Traditional” school, it is likely those categorized as “Postmodern” would reject being lumped together. |

| 4 | One might say that only soundness, not validity, assumes truth. This, however, is not Habermas’ target. |

| 5 | (Derrida 1998, p. 140). Derrida here does not capitalize or italicize “the genealogy of morals” and therefore may be refering to the process rather than the texts itself. |

| 6 | Nietzsche often relies on selecting his audience based on multiple readings. If you read his text once through, you will get one impression. If you read it several more times, you will have different impressions. For example, once one finishes the third essay discussing the “Will to Truth”, the preface appears in a different light. The very first line is actually about our epistemic access to ourselves, not morality per se. He writes, “We are unknown to ourselves, we knowers: and this for a good reason” (GM Pref. 1). On a first reading, however, one simply rushes by this indication of the text’s topic. Nietzsche also foreshadows the end of the book, writing, “But against these instincts an even more fundamental mistrust, and ever more deeply delving skepticism expressed itself in me! Precisely here I saw the great danger of humankind, its most sublime excitement and seduction—where to? to nothingness?—right here I saw the beginning of the end, the stopping, the backward-looking weariness, the will turned against life […] nihilism” (GM Pref. 5). Here Nietzsche has given away, in part, the ending. However, because this section is framed within the debate of compassion, it does not give away the whole story just yet. It is still plausible to understand this text as one about morality. |

| 7 | Georg Brandes sent a letter to Nietzsche on 26 November 1887 stating that he had received a copy of GM (KGB iii 6:120. Nr. 500. Georg Brandes to Nietzsche in Nice) |

| 8 | KSB 8, 111. Number 877—An Constantin Georg Naumann in Leipzig. |

| 9 | KSB 8, 114–115. Number 879—An Constantin Georg Naumann in Leipzig. |

| 10 | KSB 8, 115. Number 880—An Constantin Georg Naumann in Leipzig. |

| 11 | GSA 71/27.1 (https://ores.klassik-stiftung.de/ords/f?p=401:2:::::P2_ID:75094). Accessed 4 April 2022. |

| 12 | GSA 71/27.2 (https://ores.klassik-stiftung.de/ords/f?p=401:2:::::P2_ID:75097). Accessed 4 April 2022. |

| 13 | The KGW contains what are called Nachbericht volumes that detail the development of the text and cross reference it. Thus far, only one Nachbericht has been published in division VI and that is for volume 1. What this means is that there is no Nachbericht volume for The Genealogy of Morals. There is, however, some limited information in the Kommentar of the KSA (KSA 14, pp. 377–78). |

| 14 | This should not be confused with another manuscript that also bears the reference number E40 (Shelfmark: HAAB C 4620). I believe this older reference system was intended to help identify manuscripts that culminated in a final work. It is no longer used. |

| 15 | HAAB C 4616. “Zur Genealogie der Moral [Korrekturbogenexemplar],” p. 9. (https://haab-digital.klassik-stiftung.de/viewer/!metadata/1649471971/9/-/). Accessed 4 April 2022. |

| 16 | KSB 8, 163. Number 922. |

| 17 | https://ores.klassik-stiftung.de/ords/f?p=406:2:::::P2_ID:981. Accessed 4 April 2022. |

| 18 | As one review pointed out, this could be alternately rendered as: “Finally, that I indicate at least with one word on an uncanny and still entirely (wholly) undiscovered fact, which has become fixed in me slowly, slowly: up to now, there were no more fundamental problems than the moral; it was its driving force from out of which all great conceptions in the realm of values up to here have taken their origin (—All thereby which is commonly named philosophy: and this up to the last epistemological presuppositions). But there are still more fundamental problems than the moral: these come first into sight for one when one has moral prejudice behind oneself, when one knows to see oneself as an immoralist in the world, in life.” While this translation does capture some aspects much better than mine, it does not clearly demonstrate the structural parity with BGE 56 which is important later in the paper. I have decided to keep my own translation. I am thankful to Andrew Jampol-Petzinger for his help in choosing a translation. |

| 19 | KSB 8, 163. Nr. 923 (https://ores.klassik-stiftung.de/ords/f?p=406:2:::::P2_ID:981). Accessed 4 April 2022. |

| 20 | The KSA and KGW does not italicize this but it is clearly underlined in the draft in the notebook. |

| 21 | KGW VIII 1, 5[80, pg. 224; eKGWB/NF-1886,5[80]—Nachgelassene Fragmente Sommer 1886—Herbst 1887. (http://www.nietzschesource.org/#eKGWB/NF-1886,5[80]). Accessed 4 April 2022. |

| 22 | The KSA, and often the KGW also, do not make it clear when Nietzsche has crossed something out. Often, the crossed out word is simply not included. This is the case here. |

| 23 | KGW IX, 3, pg 60 of N VII 3. |

| 24 | It is clear in the document and the KGW IX that “last” (letzte) is crossed out and replaced with “lowest” (unterste) which is also crossed out. It is not clear why the editors of the KSA and KGW included this word. Perhaps it is because he reaffirms “letzte” in the letter. |

| 25 | (Deleuze 1983, p. 102; Buchsbaum 1993, p. 23). For more on Deleuze’s interpretation of eternal recurrence see (Jampol-Petzinger 2022, pp. 49–55). |

| 26 | NCW Epilogue, 1. |

| 27 | GS 276. |

References

- Adorno, Theodor, and Max Horkheimer. 2002. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Edited by Gunzelin Schmmid Noerr. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, David. 2001. Reading the New Nietzsche: The Birth of Tragedy, the Gay Science, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and on the Genealogy of Morals. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Babich, Babette. 2006. The Genealogy of Morals and Right Reading: On the Nietzschean Aphorism and the Art of the Polemic. In Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals: Critical Essays. Edited by Crista Acampora. Lanham and New York: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 177–90. [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum, Julie Anne. 1993. Ascetism and the Value of Truth in The Genealogy of Morals. Episteme 4: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Maudematie. 1990. Nietzsche on Truth and Philosophy. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, Daniel. 2008. Nietzsche’s ‘on the Genealogy of Morals’: A Reader’s Guide. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1983. Nietzsche and Philosophy. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1998. Of Gramatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Nietzsche, Genealogy, History. In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews. Edited by Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 139–64. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Paul. 2011. Nietzsche’s Enlightenment; the Free-Spirit Trilogy of the Middle Period. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gemes, Ken. 2006. ‘We Remain of Necessity Strangers to Ourselves’ The Key Message of Nietzsche’s Genealogy. In Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals: Critical Essays. Edited by Christa Davis Acampora. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Michael Allen, and Keegan F. Callanan. 2012. On the Genealogy of Morals. In A Companion to Friedrich Nietzsche: Life an Works. Edited by Paul Bishop. New York: Camden House, pp. 255–78. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2006. The Entwinement of Myth and Enlightenment. In Nietzsche’s on the Genealogy of Morals: Critical Essays. Edited by Christa Davis Acampora. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 223–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hatab, Lawrence. 1987. Nietzsche, Nihilism and Meaning. The Personalist Forum 3: 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hatab, Lawrence. 2008. Nietzsche’s on The Genealogy of Morality: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jampol-Petzinger, Andrew M. 2022. Deleuze, Kierkegaard and the Ethics of Selfhood. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Scott. 2003. Morality, Agency, and Freedom in Nietzsche’s ‘Genealogy of Morals’. History of Philosophy Quarterly 20: 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, Brian. 2002. Nietzsche on Morality. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, Paul S. 2005. Finding the Übermensch in Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morality. Journal of Nietzsche Studies 30: 70–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Simon. 1999. Nietzsche Ethics and His War on ‘Morality’. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNiel, Bevis. 2021. Nietzsche and Eternal Recurrence. Cham: Palgrave Mcmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Migotti, Mark. 1998. Slave Morality, Socrates, and the Bushmen: A Reading of the First Essay of On the Genealogy of Morals. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58: 745–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrisson, Iain. 2014. Ascetic Slaves: Rereading Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals. Journal of Nietzsche Studies 45: 230–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1887. Zur Genealogie der Moral: Eine Streitschrift/von Friedrich Nietzsche. Leipzig: Verlag von C. G. Naumann. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1966. [BGE] Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1967a. [EH] Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1967b. [GM] Genealogy of Morals: A Polemic. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Paphitis, Sharli Anne. 2009. The Doctrine of Eternal Recurrence and its Significance with Respect to On the Genealogy of Morals. South African Journal of Philosophy 28: 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, William A. B. forthcoming. Ecce Homo—Notes on Duplicates: The Great Politics of the Self. In Nietzsche and the Politics of Difference. Edited by Andrea Rehberg and Ashley Dean Woodward. Germany: De Gruyter, pp. 75–93, forthcoming.

- Poellner, Peter. 2009. Phenomenology and Science in Nietzsche. In A Companion to Nietzsche. Edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, John. 2020. Nietzsche’s Values. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schacht, Richard. 2016. Nietzsche’s Genealogy. In The Oxford Handbook to Nietzsche. Edited by Ken Gemes and John Richardson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 323–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Gary. 1990. Translating, Repeating, Naming: Foucault, Derrida and The Genealogy of Morals. In Nietzsche as Postmodernist: Essays Pro and Contra. Edited by Clayton Koelb. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Soll, Ivan. 1994. Nietzsche on Cruelty, Asceticism and the Failure of Hedonism. In Nietzsche, Genealogy, Morality: Essays on Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals. Edited by Richard Schact. Berkley: University of California Press, pp. 168–92. [Google Scholar]

- Solms-Lubach, Franz zu. 2007. Nietzsche and Eraly German and Austrian Sociology. Germany: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Robert. 1994. One Hundred Years of Ressentiment: Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals. In Nietzsche, Genealogy, Morality: Essays on Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals. Edited by Richard Schacht. Berkley: University of California Press, pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- von Tevenar, Gudrun. 2016. Zarathustra: ‘That Malicious Dionysian. In The Oxford Handbook to Nietzsche. Edited by Ken Gemes and John Richardson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 272–97. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).