1. Introduction

Kinship has been traditionally conceptualized by anthropologists and sociologists as interpersonal relations established through procreation (consanguineal) or juridical means (affinal), and thus evolving through biological connections between family members or through marriage (

Read 2001). However, several authors have claimed that neither biology nor legal recognition alone are fundamental in ascribing interpersonal connections and establishing kinship bonds (e.g.,

Carsten 2000;

Nash 2017;

Strathern 1992). The practice of adding others as kin has a long history in many societies, for example, among Catholic and Protestant Christians, the practice of denoting godparents at christening creating special relationships for spiritual guidance (

Alfani and Gourdon 2012). In recent years, the terms and formations associated with intentional kinship (sometimes known as fictive or voluntary kinship configurations, or families of choice) have become less frequently used within research on mainstream white populations, while they have become more frequently used within research on marginalized groups such as people of color and gender and sexual minority groups (

Nelson 2013).

Nelson (

2013) denotes three types of non-consanguineal and non-affinal kin relationships in contemporary societies: ritual (e.g., godparents), situational (e.g., kin because of shared situation such as in an institution/community), and intentional (e.g., a non-biological and non-affinal relationship that is denoted as a kin relationship outside of a formal naming ritual or particular shared location).

In the context of most adoptions, the family is created both in the psychosocial and legal senses without consanguineal ties between the parent(s) and the child. Some authors have classified kinship through adoption as similar to kinship formed through affinal or marriage connection (

Logan 2013), whereas others have postulated a more complex relationship between kinship and genealogy when children have been adopted or conceived by gamete donation (

Nash 2017). We argue that structural open adoption arrangements by recognizing that adopted children gain from at least some degree of age-appropriate contact with their birth family and heritage may further expand conceptualizations of kinship in adoptive families. Expanded kinship formations may be evident not only with respect to inclusion of the adopted child’s birth family members, but also with regard to other individuals deemed significant in promoting the child’s identity and family relationships. Some family environments also may favor the formation of additional kinship connections; for example, in LGBT+ parented families, the practice of forming elective and intentional kinship connections (

family of choice) has become widely established (

Muraco 2006;

Weeks et al. 2001;

Weston 1991).

In the present paper, we consider kinship connections in which family membership extends beyond either the biological or affinal kin of either the adoptive parent(s) or the adopted child(ren). In the study presented here, we investigated how lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual parents conceptualized family membership and constructed a representation of their family connections (genogram or family map) around their adopted child(ren). We further consider whether lesbian, gay, or bisexual adopters differed from heterosexual adopters in their conceptions of kinship.

1.1. Kinship in Adoptive Families

Adoption can be viewed as a topic of particular interest for genealogists and social scientists in considering whether familial relationships are accumulated, sidelined, displaced, or lost (

Logan 2013). Yet, genealogical and kinship issues in Euro-American families surrounding adoption have remained relatively underexplored (

Howell 2009) albeit with a few notable exceptions (see for instance the edited collection on adoption experiences in Genealogy,

Kirton 2020).

One reason for the dearth of studies on kinship and adoption might be because most Euro-American countries historically promoted adoption as a clean break from the child’s past with the loss of all birth family relationships; in the UK, the clean break concept was reflected in the inception of the legislation with the Adoption Act 1926 (

O’Halloran 2015). Post-adoption, the adopted child was expected to make new connections to the adoptive parents and integrate into new extended family networks based upon the families of origin of their adoptive parents. In contrast, while contemporary adoption arrangements in the UK still reassign legal responsibility for the child to the adoptive parent(s), the Adoption Act 2002 recognized that openness about adoption, and carefully managed knowledge of the child’s birth family can benefit the child in developing a fully integrated sense of self identity (

O’Halloran 2015).

In the U.S. too, the challenge of open adoption has been one of the most notable changes for adoptive families (

Brodzinsky 2006). Open adoption arrangements often seem to be most beneficial for children through age-appropriate sharing of information and also may benefit adults in the child’s birth or adoptive family (

Berry 1993;

Grotevant and McDermott 2014;

Neil 2010). Nonetheless, openness also can entail feelings of anxiety, particularly when children have been taken into the state welfare system because of concern about their safety and well-being (

Loxterkamp 2009). Open adoption therefore may give rise to a degree of uncertainty and ambivalence regarding family relationships and the place of each person within one’s kinship network (

Jones 2013;

Jones and Hackett 2011). One way to resolve the dilemma of balancing the desire for openness (heritage information) against the risks of openness (contact that seems unsafe in some way) could be to include additional kinship connections, thus supporting the adopted child’s conceptualization of self in relation to family-based relationships formed beyond the barriers of the child’s birth family.

Since the enactment of the Adoption and Children Act 2002, family law courts in the UK have been mandated to consider contact arrangements with one or more birth family members. Contact arrangements between the adopted child and birth family members (parents, grandparents, aunts, or uncles) have been observed in different ways, from indirect contact (most often via an annual letterbox managed by social services) to in-person contact between all or some family members (

Neil et al. 2015;

Neil 2018). Open adoption arrangements also may widen beyond the adopted child’s birth parents, grandparents, aunts or uncles and through the adopted child’s half, full, or step-siblings who have been placed in other homes, thus including members of other adoptive parent families (or the families of their foster carers) within contact arrangements (

Monk and Macvarish 2018).

1.2. Kinship in LGBT+ Parented Families

Weston’s (

1991) seminal ethnographic work on kinship formation (“families we chose”) proposed that LGBT+ people often defied traditional genealogically-defined family relations and conceptualized kinship as a network of intentional non-biological kin. Family of choice members could be ex-partners, LGBT+ and heterosexual friends, and others without biological or partnership connection. Intentional kin for LGBT+ individuals are not necessarily instead of traditional kin, but a deliberate extension of their family networks (

Laird and Green 1996;

Weeks et al. 2001).

Oswald (

2002) identified two main processes that promote LGBT+ individuals’ family connections through non-traditional kinship: (1) LGBT+ individuals choosing their own family networks based on attributes other than biological connections (intentionality); and (2) LGBT+ individuals attaching familial names to non-traditional kin (redefinition). Studies on chosen family have shown that these relationships are comparable to and sometimes supersede biological family connections not only in terms of their emotional and symbolic importance but also in terms of practical functions such as providing care and financial support (e.g.,

Muraco 2006). However, little is yet understood about how intentional kin become incorporated and fit into one’s kinship system.

Often LGBT+ individuals’ family connections “are negotiated under varying degrees of adversity” (

Oswald 2002, p. 374). For many LGBT+ individuals, the permanence of biological kinship sometimes cannot be guaranteed because many suffer from rejection of their sexual identity and either decide or are forced to cut ties with their family of origin following disclosure of their gender or sexual identity (

van Bergen et al. 2021). Thus, partnerships and non-biological parentage may go unrecognized by family of origin members. Nevertheless, in many western industrialized societies, including the UK where the present study was conducted, same-gender marriage and parenting, including through adoption, are now legally available, thus allowing LGBT+ individuals to have partnerships and parentage legally and socially sanctioned (

Costa 2021), and “in general, kinship construction in the family arrangements takes a more flexible, inclusive, and open forms where legal recognition exists” (

Furstenberg et al. 2020, p. 1413).

Adoption has been an option open to same-sex couples in the UK since the Adoption and Children Act 2002 came into force in 2005. Most studies of LGBT+ adoptive parent families have focused on the children’s overall psychosocial adjustment and adjustment to adoption, and overall have shown that children adopted by LGBT+ parents display similar psychological adjustment as those adopted by heterosexual parents (

Tasker and Bellamy 2019). In addition, LGBT+ adopters are as capable at childrearing as heterosexual adopters (in the UK, see for example

Costa et al. 2021;

McConnachie et al. 2021). Extrapolating from the general willingness of LGBT+ adults to create family of choice networks unbounded by biological or partnership ties, could it be the case that lesbian, gay, and bisexual adoptive parents demonstrate greater openness than do heterosexual adopters to forming intentional kinship connections for their child(ren) in a legal context that promotes open adoption? Studies have shown that compared to heterosexual adopters, many more LGBT+ adopters and prospective adopters decide upon adoption as their preferred route to parenthood because they do not prioritize biogenetic kinship (

Costa and Tasker 2018;

Jennings et al. 2014). US-based studies have shown that lesbian and gay adopters tend to have greater contact with their child’s birth family, more face-to-face and telephone contact, and a more positive experience with these contacts than heterosexual adopters (

Farr and Goldberg 2015;

Brodzinsky and Goldberg 2016,

2017).

Goldberg et al. (

2011) attributed these findings to lesbian and gay parents’ greater sympathy towards open adoptions because of a spirit of honesty and openness that characterizes these arrangements, and consequently, LG adopters frequently incorporate the child’s birth family as part of their extended family network. Previous qualitative interview data from the UK have suggested that the kinship systems of LGBT+ adopters and foster carers are diverse and motivated by the care needs of their child to include the child’s previous foster carers, friends, and others alongside members of the adopted child’s birth family (

Wood 2018). However, a few studies have also suggested that contact with birth families is not without its difficulties and can sometimes lead to an elevated risk for LGBT+ individuals to abandon adoption as a route to parenthood (e.g.,

Goldberg et al. 2019).

1.3. Research Aims

Our main purpose in this study was to explore how lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual adoptive parents define and depict their family networks beyond biological and affinal kinship connections. Here, we focus on examining how parents integrated intentional kin when mapping or drawing out and talking about their child’s family network. We addressed the following research questions in our study: (1) Were lesbian, gay, and bisexual adoptive parents more likely than heterosexual adoptive parents to include intentional kin on their family maps? (2) What was the basis of the intentional kinship connections formed by adoptive parents, and were there systematic differences between the types of intentional kin connections included by lesbian, gay, bisexual, or heterosexual adoptive parents? and (3) What roles did intentional kin perform in adoptive parent families? Did roles differ between different types of adoptive parent family?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study presented here is part of a larger research project titled “Empowering Adoptive Families: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Child Well-Being in Adoptive Families” (EAF). The EAF research project used a mixed-methods study design to examine parents’ and children’s well-being in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual parented families through adoption. The first wave of the project collected quantitative and qualitative data from parents through an online survey. The second wave of the project collected qualitative data from a subsample of parents and their children. Detailed information about the 253 adoptive parents and study design from the first wave of the project is available from (

Costa et al. 2021). Parents who completed the online survey in the first wave of research were invited to provide contact details at the end of the survey if they would like to participate in a qualitative study, the second wave of the project.

Here, we report verbal and visual interview data from parents who participated in the interviews conducted during the second wave of the project (“Mapping Family Relationships”). This wave of the project employed qualitative methods within a descriptive cross-sectional research design, using non-probabilistic intentional sampling. Inclusion criteria for the research project were that: (1) the parent(s) had adopted at least one child; (2) the child(ren) had been adopted at least 12 months prior to participation; and (3) the child(ren)’s age at time of study was between 5 and 18 years.

2.2. Participants and Procedures

The interview study sample comprised 25 adoptive families: 7 gay/bisexual parented families (FAMG), 6 lesbian/bisexual parented families (FAML), and 12 heterosexual parented families (FAMH), all of whom were interviewed by the first author. All participating parents lived in the UK and all but two had adopted their children in the UK through domestic adoption from public care. Two families had adopted their children internationally, one from Asia and one from South America. Nonetheless, some parents and children had other nationalities. Two families lived in Scotland while the majority lived in England. Aside from their adopted children, one of the heterosexual parents and two of the lesbian/bisexual mothers also had biological children, and one heterosexual mother had stepchildren. All parents in this study had some contact arrangement with their child’s birth family. For participants’ convenience, 21 parents were interviewed in person at their home, office, or in a public venue (e.g., local park), and four were interviewed online.

Table 1 describes the family composition of the parents that participated in this study.

Before the interview, parents were given an information sheet and consent form explaining the aims of this study and what they would be asked to do (interviewing and drawing their family map). Signed informed consents were collected from all parents. After the interview, parents were verbally debriefed by the interviewer and were given a debrief form with contact details from the research team and post-adoption support services. Parents were also offered a free counseling session by the research team’s psychotherapy consultant if they felt that their participation had induced any psychological or emotional distress. Both waves of research were assessed and approved by Birkbeck’s Department of Psychological Sciences’ Ethics Committee (161774/161775).

2.3. Materials

The interview script developed for this study to examine family relationships, inclusion, and closeness of relations, was based upon the family mapping exercises (FME) for adults (

Tasker et al. 2020). FME have been developed specifically for LGBT+ parented families who are more likely to define their family more broadly and both inside and outside the boundaries of biological and affinal kinship usually denoted in genograms (

Swainson and Tasker 2005;

Tasker and Delvoye 2018). Genograms are usually part of a therapist’s set of techniques and thus offered to clients as part of a therapeutic intervention. In addition, ecomaps, or ecograms, employ a systemic and ecological approach to family relationships to highlight the presence or absence of family resources (

Hartman 1978;

McGoldrick 2016). The FMEs combine both the genogram’s approach to family relationships and the ecogram’s flexibility to depict systems and resources, anchored in a constructivist epistemological standpoint in which participants are given freedom to define and depict their family, kinship, and identities in their own words and symbols.

In the adult version of the FME adapted for the present study, participants were presented with blank pieces of paper, pens, and colored pencils, and asked to a draw their family using marks, symbols, or drawings for each person that they considered to be part of their adopted child(ren)’s family. When interviewing a parenting couple, participants were given the option to either do their family map individually or together. The interview script was semi-structured, and aside from the standard FME instructions for adults, we added a few questions covering the following predefined themes: (1) openness about adoption, both inside and outside the family (e.g., family system, school system); (2) openness about family configuration, both inside and outside the family (only for LGB parents); (3) contact and relationship with the child’s birth relatives; and (4) other important people included or not included on the family map. Interviews lasted on average 60 min (ranging from 18 to 180 min).

2.4. Data Analysis

Two types of analyses were conducted on the visual (family maps) and the verbal (interviews) data gathered from the family map interviews. Each family map was transposed by two research team members into individual Microsoft Word document preserving all depicted wording, features and proportional distances, but using pseudonyms for all included figures. For the purposes of the current analysis a table was compiled noting the inclusion or non-inclusion of non-biological and non-affinal kin, and their role in the family for each family map representation and associated interview script.

The audio recording of each interview was initially transcribed verbatim by either a research team member or a professional transcriber. Each transcript was then checked against the audio recording by the interviewer and participants’ names and all other names mentioned were replaced in the transcript by the pseudonyms deployed in the participant’s family map. During this initial process of transcript review, any mention of a location, an institutional name, or any other possibly identifying information was either omitted from the transcript or disguised to preserve the family’s anonymity. Interview transcripts were then considered as verbal interview data alongside the visual data contained in the participants’ family map.

In the present study, we have selected quotes from the transcripts that verbally describe the relationships participants drew on their family maps; these quotes were often said while drawing a figure or connection on to the family map.

3. Results

3.1. Inclusion of Biological, Affinal, and Intentional Kin on Family Maps

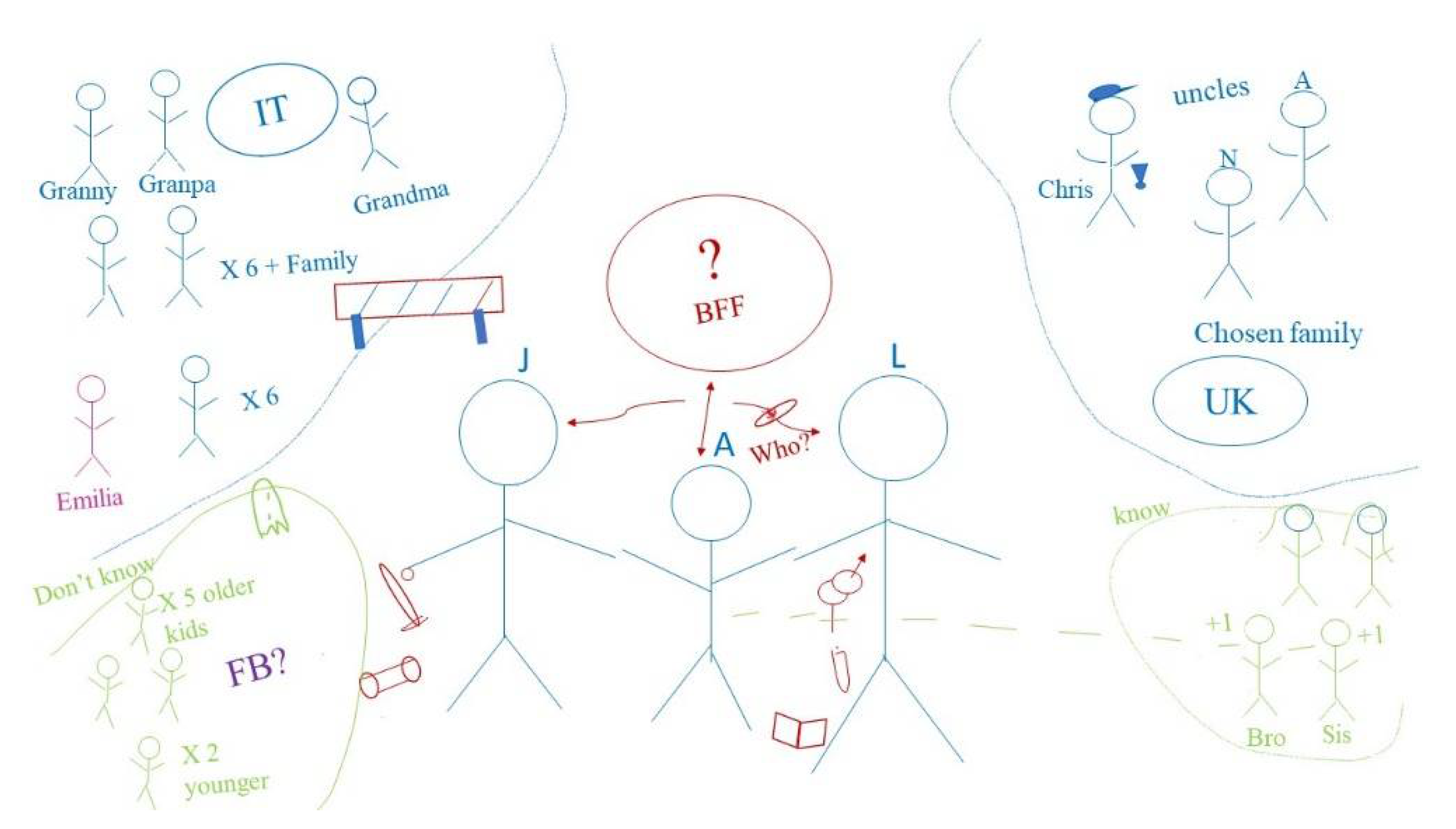

Adoptive parents included biological, affinal, and intentional kinship relationships on their family maps. Parents represented kinship relationships around a core family group—the adoptive family—that was usually drawn first at the center of the family map: “This little unit, that is central to everything”. (FAMH3, different-gender couple). As an example, a core adoptive family unit is depicted in a heart-shaped figure in

Figure 1, alongside kinship connections. In all but one case, adoptive parents drew their children at the center of the core family group and any children born to one or both parents through heterosexual conception or Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). Adoptive parents then usually proceeded to represent other kinship connections (usually where kinship was established through biological relatedness or partnership connection) and thus included their own extended family and their adopted child’s birth family on their family map representations. In the present study, we focus on examining the intentional kinship connections that adoptive parents also included on their family maps.

Of the 25 families in our study, two thirds (

n = 16) depicted intentional kinship connections on their family maps. These included parents’ connections prior to adoption, connections developed during the adoption process, or important connections formed by their adopted children. For example, in

Figure 1 the adoptive parents included their children’s previous foster carers. These intentional kinship relations were usually drawn after biological and affinal kinship relations.

We compared intentional kin inclusion indicated on family maps drawn by lesbian, gay, and bisexual parents with those included by heterosexual parents through contingency table analyses using Fisher’s exact tests to test for statistical significance. Specifically, we created a set of variables regarding the inclusion of intentional kin on the parents’ family maps and/or verbal mention of non-traditional kin during the interview. In

Table 2 below, we first considered whether there were any differences in the inclusion of intentional kin per se between LGB and heterosexual adoptive parents. Subsequently, we examined adoptive family type differences on the inclusion of intentional kin; and specifically (1) adults with longstanding connections with parents; (2) other adoptive families; (3) child’s previous foster carers; and (4) others connected to the child. No significant differences were found between the two types of families (LGB vs. H) on any of the compared types of intentional kinship.

While intentional kinship connections varied along these types of connections explored in

Table 2, all four types of intentional kinship could be seen as supporting a key aspect of a parent’s identity (e.g., as an LGB person; as an adoptive parent) and/or of the adopted child’s history and identity (e.g., previous foster carers; a person of similar cultural/ethnic heritage).

3.2. Adults with a Longstanding Connection to One or Both Parents Predating Adoption

Some intentional kin figures represented on family maps were people with a connection to one or both parents that predated the adoption. These longstanding friends of the family were as likely to be represented on the family maps of heterosexual adopters and lesbian, gay, and bisexual adopters. For most heterosexual adopters, these figures were described in terms of the importance they had for the parents, and by extension for the family as a whole: “Other people that I could include in this are my friends, so, we’ve got two very good friends that Nicole [adoptive daughter] loves to spend time with (…) we met on our first day at the university” (FAMH6, H single mother). For LGB adoptive parents, most of these connections had been forged through their involvement in the LGBT+ community, but also went on to play an important role in the adopted child(ren)’s life. Oftentimes, intentional kinship was ascribed by adoptive parents as “uncles” and “aunties” to the child(ren) and all were viewed as trusted people: “Alex [adoptive son] has kind of three guys that are really good friends of ours, that he considers, I guess uncles, sometimes he calls them uncles. But they’re friends of Jamie and me” (FAMG1, same-gender couple). The inclusion of LGB intentional kin on a family map was particularly noticeable among LGB adoptive parents who did not have biological or affinal kin living near-by. For these parents, their friends were intentionally trusted with particular family tasks to ensure the well-being the child:

“I think Andrew may come in handy when he [adoptive son] becomes a bit older, when he needs a serious conversation with someone. And they’re also the kind of designated, ‘if you want to ask a grown up something and you don’t want to ask us, ask them’, and they know they don’t have to tell us. As in, if it’s a ‘I have a girlfriend’ or ‘I need to buy condoms’ or something like that (…) That’s somebody that he can talk to that is a trusted adult, besides us”

(FAMG1, same-gender couple).

3.3. Other Parents with Adopted Children

Many adoptive parents mentioned other adoptive families during their interviews as important sources of support for them and their adopted child(ren). However, only four out of 25 parents specifically included them on their family maps: two heterosexual parents, one LB mother, and one same-gender couple. Adoptive parents who included other adoptive families as kin connections tended to stress the importance of these connections for themselves, insofar as they exchanged experiences and advice regarding the ongoing adjustment of their adopted child to the family:

“His mum will ring me up and say, ‘Peter’s talking a lot about and is really upset about his birth mother and is worrying about her’. You know, you have these sorts of conversations, or I say, ‘Liam said that the other day’, oh really, ‘Peter’s started saying that’, and sometimes you see things are happening at the same time... or not happening at the same time (…) It’s sort of a reality check, I suppose”

(FAMH3, different-gender couple)

Aside from any specific inclusion on their family map, adoptive parents mentioned other adoptive parents as a unique source of social support throughout the adoption process. For some LGB adoptive parents, there was also a particular connection with other sexual minority adoptive parents that were forged through the adoption process:

“It was a support group for lesbians and gay men who were adopting children, it was very specific, and Abbie and I went to the group and met two other women called Scarlett and Ella, who were also like me, just about to adopt or go through the adoption process (…) We were supporting each other through the adoption process, which we really did, and it was actually really good, and essential that we were all together and doing that together, and just don’t know how it would have been without those three women because just every stage of the adoption process, we met every week at least, and we all knew exactly what was happening with each other and we could compare notes, and three of us even have the same family placement worker here”

(FAML4, LB single mother).

Connections with other adoptive parents did not predate the adoption but had been formed through the adoption process or subsequent to it. Most local authorities and many agencies ran group sessions to give prospective adopters initial information about adoption. Depending upon the service provider, group-training sessions often continued throughout the adoption process and beyond. Nevertheless, many of the intentional kinship connections with other adopters began during the first phases of their adoption process. From these groups, strong friendships formed, and as their respective adopted children grew up, adoptive parents gained much support from each other, emphasizing the importance of these relationships in recognizing and sustaining the adoptive parents’ relationship with their child.

Given the unique aspects of the transition to parenthood through adoption, it was perhaps not surprising that participants in our study often felt that they had much in common with other parents who had adopted. As one participant said when drawing her family map: “Sometimes people with birth children don’t necessarily always get” what adoption issues in fact are. This parent then continued:

“I think quite often we talk about things, about attachment, and issues around control and stuff, that perhaps, because we’ve read the books and been in the class we become very, perhaps over obsessed with this (…). I suppose I think we’re experts on our children in a way. So I think that’s why there is quite, you have a shared set of experiences”

(FAMH3, different-gender couple).

Sometimes participants also stated that the support of another adoptive parent was distinct from that given even by a helpful professional social worker. Another adoptive parent would have had a similar challenging experience to their own:

“It was such a long process, and, even though my social worker was really good, I just wished that I could have somebody that I could speak to about the process, who understood it. The social workers understand, but they don’t really, but they can’t really know what it’s like to be going through that process”

(FAMH6, H single mother).

Participants also described intentional kinship connections formed around adoption as being very relevant for their adopted child through enabling their child to grow up knowing another child who had been adopted. Adoptive parents described the advantages of this for their child in having a child like them who they can talk to about their experience, and therefore experience adoption as something not to hide or be ashamed of, but to be valued:

“Paige [adopted daughter] is with a girl called Emma this afternoon, who’s adopted. I’ve only just found this, in the last couple of years, this family, they’re in this borough. So there’s another adoptive family there, so we’re thinking of setting up a support group for our girls, as they go through their teenage years, so we’re talking about a support group for Emma and Paige and a couple of other girls”

(FAML4, LB single mother).

3.4. Foster Carers

Generally, most participants expressed their gratitude to the foster carers who had looked after their adopted children prior to adoption, even if they were no longer in regular contact with them. Participants felt that foster carers had genuinely helped a child in need of care to experience a consistent and kind domestic routine, thus preparing the child for the transition into the adoptive family. In a third of the cases, participants included the adopted child(ren)’s foster carers on the family map drawing. Often this seemed to be linked to recognizing the importance of an ongoing relationship with the foster carers.

For Jessy and her wife Stephanie (FAML2, same-gender couple), all the household family members of the different-gender couple who had fostered Jessy and Stephanie’s son Samuel prior to adoption were included in Jessy’s family map. Jessy considered the foster carers to be permanently part of their family because of the love and care they gave to Samuel and their continued interest in him. The link between these two families became so strong that Jessy described the foster carers and their family as “now bolted permanently” to Jessy’s family: “I sort of considered that we inherited them as a family as well because they feel a bit like in-laws, to me, so... they had him for 14 months”. Jessy also refers to her son’s foster carers as kin, describing the foster carers’ extended family members as like her own family members: “And then Amanda [foster carer’s daughter] has got three children that sort of feel like cousins or something, and that would be what that relationship feels like, so I guess these feel like aunties to Samuel.” Jessy accorded the foster family recognition as being an “in-law relationship”, with the foster carers own grown-up daughters being referred to as aunties to Samuel.

It was not uncommon for participants to use kinship lexicon to place the foster carer within the family. Furthermore, the importance of the foster carers for children’s own definition of family was highlighted by some parents:

“They [adoptive sons] think of them as their foster carers and they’re fond of them. The foster carers were very good. Occasionally our boys will refer to the fact that they’ve had five fathers. They don’t know about their biological father (…) so they speak of their foster father as a father and then the two of us”

(FAMG7, same-gender couple).

Miley (FAML1, LB single mother) also included foster carers on her family map not only in recognition of the love and care they gave Miley’s daughters prior to adoption but also because these foster carers could provide a link to her daughters’ birth family and help to piece together some of the children’s cultural heritage. Miley was a single White-British lesbian mother who had adopted two Black African half-sisters, who were both placed in the same foster family when they were 3 years and 3 months old. The children’s birth family and the foster family were both Black African albeit from different countries. Miley clearly valued her children’s cultural heritage and also included long-standing intentional kin connections of hers on her family map, who helped to sustain her daughters’ Black African ethnic identities.

3.5. Other Intentional Kin

Two other distinct groups of intentional kinship connections were included on the family maps drawn by adoptive parents: children who were named as the best friend of the adopted child and people who had been very involved in caring for the child over a substantial period of time. Usually the central focus of these intentional kinship connections was the closeness of the adopted child to that person, not necessarily the adoptive parents’ connection with them:

“So we have another close friend who adopted at the same time as us through the centre where we adopted Adrian (…) and so the three of the children were very close, they were like brother and sister almost in many ways. (…) He has got two particular close friends who he met, well one of them the first day at secondary school, who lives round the corner, and they’re like brothers as well ‘cause we’ve known Andy since he was eleven, and Adrian was eleven, and I’ve been a carer to Andy”

(FAMH1, two sisters).

Furthermore, when the child did not have a best friend or close friend connection, this seemed to be felt by parents as a missing piece in the child’s family network: “The piece that’s missing is Alex’s best friend. Because there isn’t anybody that he would consider a best friend, like he has friends and kids that he hangs out with at school, but there’s nobody that’s here every day” (FAMG1, same-gender couple). For these parents, who often had included their own best friend(s) on their family map specifically as “chosen family”, these relationships were seen as important for their child’s well-being and the parent seemed eager to embrace them as kin (see

Figure 2).

Aside from the adopted children’s best friends, other adult figures were sometimes included by adoptive parents on their family maps. These were adults who were not related to the adoptive parent or their child by a biological connection, partnership, or adoption per se but were included on the family map because they played an important part in the adopted child’s life. Some of the adults included on the family maps lived locally as close neighbors to the adoptive family and had gone out of their way to help the family in taking care of the child(ren). Other adult connections included were professionals who had a long-standing involvement in the child’s life. Different family maps featured different groups of professionals: social workers, pediatricians, psychologists, nannies. For Paul and Diego (FAMG2, same-gender couple), a social worker who had become professionally involved with one of their sons during his early life had become an important member of Paul and Diego’s family and was given the place of “godmother” to their son: “Virginia was someone who worked professionally with Cody as a small kid, and she has remained part of our, I mean the boys, when I say their circle and support network, and if you like, family”.

Even if in some cases these figures had not been as helpful as the parents had at times wished, they were still mentioned by the adoptive parents because they had improved participants’ lives, supporting them not only in the first phases of the adoption process or placement, but also in becoming involved again years later. For example, if an adolescent started to think about finding out more about their biological family and perhaps about making contact with them:

“We had a really nice social worker called Lucy, and we got to know her really, really well, and she actually retired just after we got Nicole. And because she retired out the service, she gave me her private number; we stayed friends, actually, we still send Christmas cards and give updates (…) Another reason why I want to postpone it as long as possible [mediating contact with her daughter’s birth family], until she’s emotionally able to do that. And I’d like to have the social work input before we get to that stage”

(FAMH6, H single mother).

3.6. The Roles of Intentional Kin Members in Adoptive Family Life

None of the intentional kin included on parents’ family maps lived in the same household as the adoptive parent(s) and children. Therefore, intentional kin were not generally involved in everyday childcare. Nevertheless, adoptive parents sometimes highlighted the role that intentional kin played in helping out with the children, for example by giving regular or occasional childcare:

“I’ve got friends who are really supportive and have been there for a long time (…) In fact, Elisabeth said the other day, doctor Ashanti—her name’s Ashanti, or doctor Ashanti, because she’s a doctor—and she said she’s more like our ‘something’—and it was a kind of a family term, even though we don’t see her that often—but she’s taken them out, you know, without me”

(FAML1, LB single mother).

For others, childcare by other significant adults happened in the context of an expansive family connection between the adoptive family, including both parents and child(ren) and other families:

“Charlotte, our neighbour, she’s quite significant and close because she lives across the road, and she’s a very close friend of ours, and her family—they’re Greek, so there’s a very big family, Greek culture. So he calls Charlotte’s mum ‘Yiayiá’, he says grandmother and granddad in Greek for them, so he sees them as his nanny and granddad as well. (…) And we get together on big family occasions, and we’ve just had a big family wedding for her daughter, so he’s been involved with all of that as well. But because she lives across the road she’s always popping over, and if he forgets his keys he goes over there to get his keys… She looked after him, he would go over there as well for tea”

(FAMH1, two sisters).

It was also clear that adoptive parents relied on their intentional kin as part of the wider support network, but that the support given by intentional kin was not exclusive to help with parenting and childcare. In fact, some parents mentioned having varied support from a wide variety of intentional kin connections:

“I’m still very close to Scarlett [parent’s friend], who’s got two kids around Madeline’s age actually, one Madeline’s age and one a little bit older; it was her car that I borrowed this afternoon that I had to return. So I’m very close to Scarlett, she’s still around very much (…) And then I’ve got other friends in the area. I’ve got Madison, I’ve got Brooke, I’ve got another Brooke, one of whom I used to have a relationship with. So all these people are all around, and Lauren too. That’s my support network (…) I’ve got a good support network”

(FAML4, LB single mother).

4. Discussion

In this study, we aimed to examine how adoptive parents integrated biological, affinal, and intentional kinship in their family network and whether the basis for intentional kinship connections formed by adoptive parents differed in heterosexual compared to lesbian, gay, and bisexual parented families. We analyzed the family maps and interview data of 25 adoptive parents in terms of inclusion and description of intentional kinship connections and considered the roles that these figures played within the family. We found that two thirds of the adoptive parents specifically mentioned and included intentional kin on their family maps. Intentional kin depicted on family maps included parents’ friends, children’s foster carers, other adoptive families, and other figures connected to the parents, the child, or both. Notably, the most often depicted intentional connections (10/16) were adults with a longstanding connection to the adoptive parents, closely followed by children’s previous foster carers (9/16). No significant differences between the family types were found when comparing the likelihood of inclusion of intentional kin on the family maps of LGB and heterosexual adoptive parents. Further, no family type differences were found with respect to the inclusion of specific types of intentional kinship connections either. Although the sample in this study was small and recruited through non-probabilistic sampling and limited to the particular context of adoptive families in the UK, these findings suggest that structural open adoption is likely to promote an expanded consideration of belonging in kinship networks, regardless of parents’ sexual orientation and family configuration. Nevertheless, we need to caveat this with a limitation of sample size, necessitating the aggregation of lesbian, gay, and bisexual parents in one group of families, thus perhaps overlooking potential differences between sexual minority parents with respect to intentional kinship.

Based on the analysis of verbal and visual data, we identified three main roles attributed to intentional kin: (1) preserving and valuing the adopted child’s story, (2) preserving and affirming the adopted child’s identity; and (3) providing a support system for the adopted child and adoptive parents. As

Nelson (

2013) has argued, sometimes intentional kinship may be formed out of situational kinship as the relationships transforms and continues beyond its original setting—a phenomena which was particularly striking when the adoptive family relationship with the foster carers continued for years beyond the foster carers stated temporary and statutory role in the child’s life. Adoptive parents appeared to view the foster carers as stand-in or proxy parental figures during their child’s early years, providing practical support and care. Adoptive parents also suggested that maintaining this connection with their child’s previous foster carers would be important for the adopted child’s sense of self and in piecing together their story. Foster carers were often perceived as gatekeepers for an important part of the adopted child’s history, which parents felt was important to preserve and actively keep a connection with, perhaps mirroring the important transitional role that foster carers play in preparing the child in their journey through the state care system to their placement with their adoptive family (

Newquist et al. 2020) While most adoptive parents mentioned the foster carers during the interview, about one third of them placed them within their kinship network, mostly because they were custodians of the memories of the early years of their children’s lives and were influential figures at such a delicate point in their children’s lives. Maintaining a connection with the foster carers further offers some sense of continuity for the adopted child who had suffered significant changes and losses in their early relationships, For some adoptive parents this special connection meant maintaining periodic contact, whilst for others these figures were “bolted permanently” to their family, with one parent referring to their child’s previous foster carers as their “in-laws”. In short, some adoptive parents attached a symbolic significance to the ongoing foster carer relationship for which there is no traditional available semantic. Importantly, the adoptive parents expressed both of

Oswald’s (

2002) concepts of

redefinition and

intentionality in integrating these figures as their kin sometimes even under circumstances where the child had been so young when placed with their foster carers that this was beyond the child’s earliest memories.

Aside from foster carers, some parents mentioned forming or maintaining close connections with others who shared a common identity with their adopted child. For example, cultivating connections with other adopted children or with others from a cultural background at least similar in some respects to that of their child to help the child value their cultural heritage, which has been shown to be an important feature in creating kinship (

Jones 2013;

Jones and Hackett 2011). In fact, US studies have shown that adoptive parents from an ethnic minority and those who had adopted children from an ethnic minority actively engage in their children’s socialization around race and racism and draw support from similar cultural and ethnic communities to preserve their children’s cultural identity (

Goldberg and Smith 2016;

Richardson and Goldberg 2010). Some adoptive parents also developed their kinship networks based upon a need for community support, particularly those who may have not had biological kin living local to them, which

Jones (

2013) refers to as situational kin. “Uncles”, for example, were expected to be involved in childrearing and entrusted with important family tasks, such as communicating and advising the children/adolescents in topics that may not always be easily discussed within a parent–child dyad. For some parents, the assimilation of kin was based on their perception of their child’s needs, namely, by including their child’s friends or professionals who had become trusted figures for the child. For example, intentional kin connections included trusted adults who had supported the child in their journey into adoption and who could support the child through future challenges such as finding out more about their birth family history.

Adults with a longstanding relationship to the adoptive parents were mentioned and included on the family maps of some of the participating parents in our study. Long-time friends of the adoptive parents were given a special place within the family, not only because of the significance they had for the participant as a source of social and emotional support over many years, but also because of the role they had been ascribed in caring for the participant’s adopted child. Adoption plays such an important and defining feature in participants’ families that for some parents, friendships forged through the adoption process fostered a sense of belonging with other adoptive parents. In addition to the structurally open adoption that characterizes all UK adoption placements in this study, fostering close connections with other adoptive families suggests a communicative openness about adoption both within and outside the adoptive family unit. Communication openness about adoption has been shown to promote the developing child’s well-being, psychological adjustment, and better overall family functioning (

Brodzinsky 2006;

Grotevant and McDermott 2014). For the adoptive parents in this study, familial connections with other adoptive families were often intentionally pursued with the purpose of allowing children to communicate and express their feelings about adoption outside the immediate family to others in a similar situation, in turn contributing positively to the adopted child’s well-being.

Negotiating intentional kinship connections seemed to serve different functions for the adoptive parents in this study, although they were all focused on ensuring the well-being of the adopted child within a large and supportive network. Other important intentional kin included on adoptive parents’ family maps included children’s best friends and adult professionals who had become involved in the child’s life prior to or during the adoption process. Further, children’s friends tended to be recognized as kin especially by adoptive parents who also included their own best friends on their kinship network, thus suggesting a conscious and deliberate expansion of kinship.

Naming important family connections and identifying the role of these connections within the family network is a process that promotes kinship assimilation (

Finch 2008). Adoptive parents referred to relationships often in terms borrowed from the traditional family lexicon when explaining particular relationships or when making sense of the complex web of relationships formed through open adoption. Some parents ascribed specific names and traditional roles to trusted figures such as “uncles/aunts”, “brothers” or “in-laws”. As

Muraco (

2006) purported, these relationships are both normative and transformative, so that in the absence of familial semantics and social scripts for these intentional connections, adoptive parents established kinship both within and outside traditional norms. This finding is in line with previous recommendations to consider broader symbolic and institutional aspects of family and kinship (

Monaco and Nothdurfter 2021). It thus follows that “chosen families” (

Weston 1991) are not exclusive to lesbian, gay, and bisexual adoptive parents, and that UK adoptive parents are likely to pursue an intentional extension of their kinship networks that seems to be promoted by the process of adoption (

Brodzinsky 2006;

Oswald 2002). We suggest that the shift in adoption towards openness and contact with different family networks (e.g., adopted children’s birth family and foster carers) enacted in the Adoption and Children Act (2002) promoted an important redefinition of what a family is, wherein kinship is established upon social and emotional connections between adoptive parents and their children and significant others. Nonetheless, our conclusions are tentative, and we suggest that future research replicate our findings with a larger sample. The extent to which kinship is expanded for adopted children is still an underexplored topic (

Furstenberg et al. 2020). We suggest that future research should examine adopted children’s conceptualization of family and kinship, and whether children’s definition of kinship correspond to their parents’ expanded definitions.