4. Rüsen’s Disciplinary Matrix as an Analytical Tool

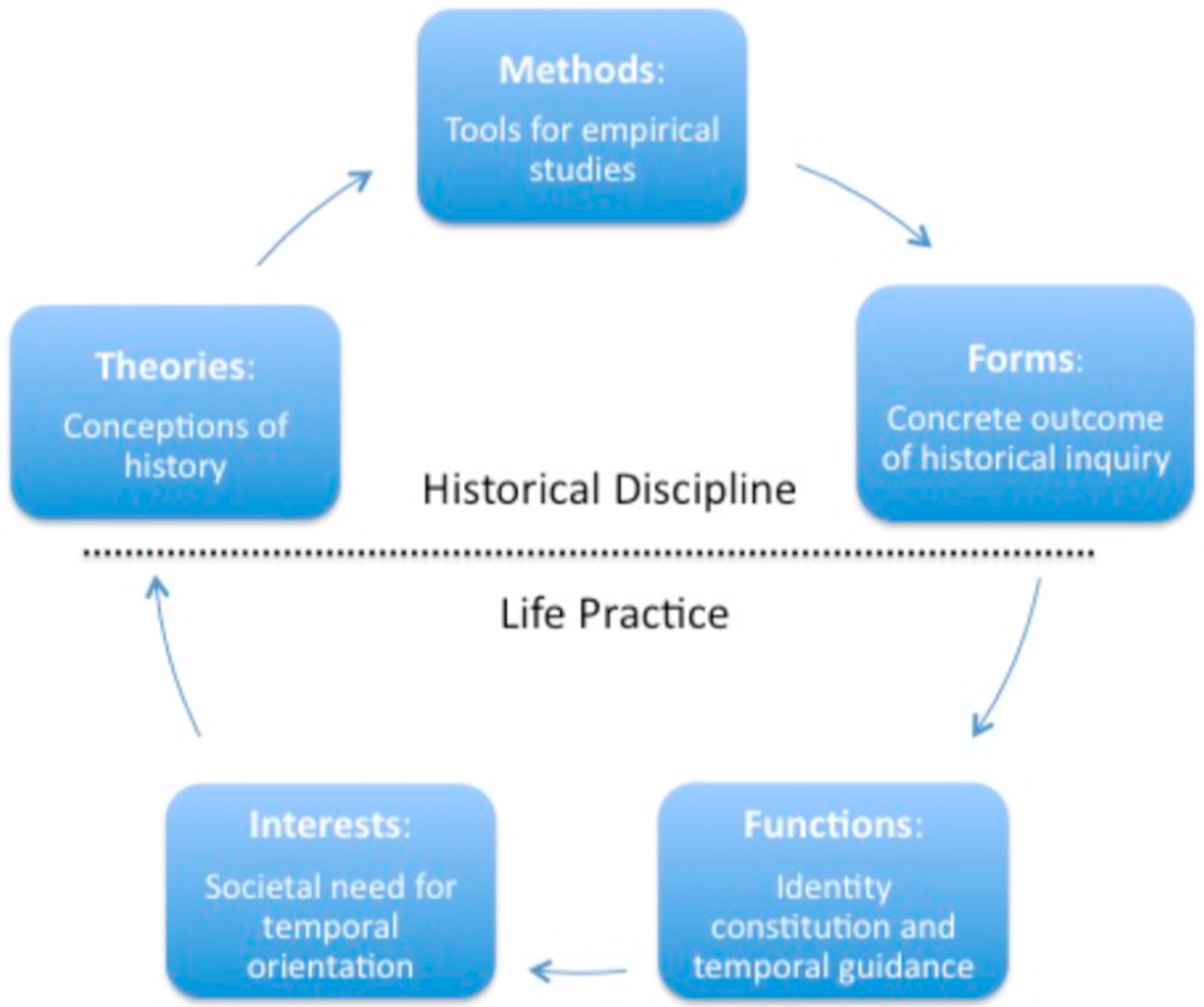

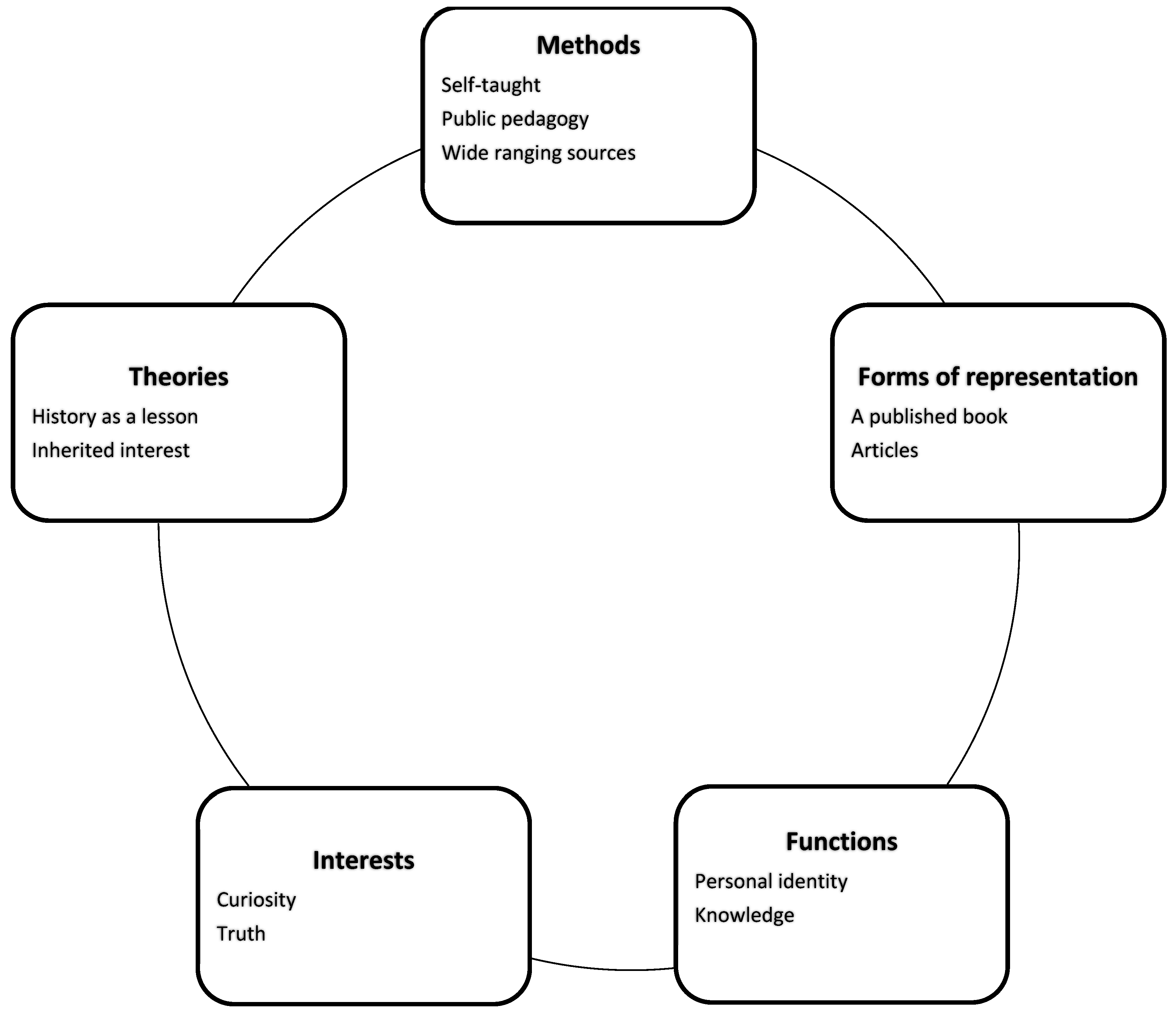

Jorn Rüsen (

1993) developed a Disciplinary Matrix which embraces five central factors or principles of historical thinking: the cognitive interest of human beings in having an orientation in time; theories or “leading views” concerning the experiences of the past; empirical research methods; forms of representation; and the function of offering orientation to society (

Megill 1994). Within the matrix, Theories (

conceptions of history), Methods (

the tools used for empirical work), and Forms of representation (

what does the result of the historical inquiry look like) are illustrative of engagement with the history discipline. Interests (

societal need for temporal orientation) and Functions (

what does the historical inquiry do with regard to identity construction and temporal guidance) relate to ‘life practice’.

Rüsen’s Disciplinary Matrix (

Rüsen 1993) describes the relationship between disciplinary historical knowledge and history in contemporary life, and how these contribute to the development of historical consciousness. The Disciplinary Matrix offers a flexible model in which to analyse how individuals interact with the discipline of history and their motivations for doing so. As

Gosselin (

2012) contends, “the strength of Rüsen’s model lies in its ability to recognise the relationship between the internal logic of the historical discipline and everyday life” (p. 59).

Chapman (

2014) concludes that Rusen’s matrix can be useful diagnostically as a tool for identifying dimensions of historical interpretation and he suggests “pedagogies informed by kind of thinking embodied in the matrix can be helpful for progressing historical thinking” and that “Rüsen’s model is a valuable tool for organising reflection on historiography and on accounts of historical practice.” (p. 70). The matrix is represented diagrammatically in

Figure 1 below.

The case studies in this paper were examined in alignment with the central factors of the matrix, and questions were developed to guide the analytic process as outlined in

Table 3 below. Rüsen’s matrix has been modified and individualised for each of the four case studies to determine the impact of family history research and its relationship to historical consciousness. These adapted diagrammatical representations, presented as

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, facilitate comparing and contrasting of the case studies.

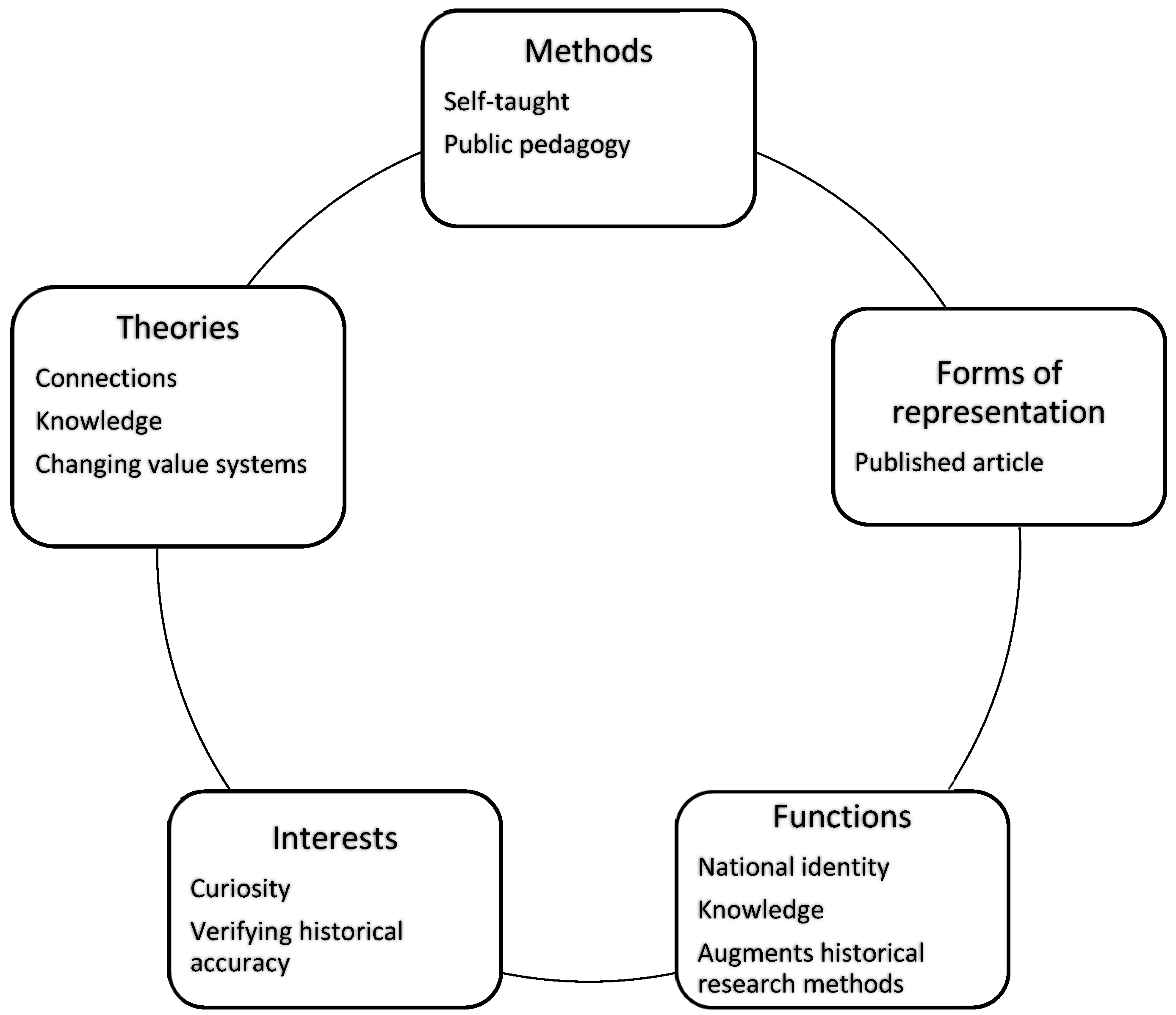

Figure 2.

Case study one in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

Figure 2.

Case study one in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

John lives in New South Wales, Australia. His highest level of educational attainment is a bachelor’s degree, and he had only formally studied history at school. He currently spends up to 40 h per week researching his family history and is a member of a historical society. John commenced his family history research in 1979 citing “simple interest” but explained that “you didn’t know what was available…it was like staring into a big black hole, not knowing what to look for or what was available, or how to go about it”. He recommenced his research in 2013 when he uncovered a family connection to a famous Australian artwork, and through his research, was able to challenge the written history of a painting of national significance. He tells that

Back when I first started in 1979, I initially spoke to my mother [about the painting]. In addition, it was only 30 years later, when I started to discover and piece together the big puzzle, and I found that…everything she said, it all fitted in.

John also revealed an interest in acquiring an increase in familial knowledge as he reported “I needed to understand not just how, not just the story of [name] in it, and what came before him, and also what came after him, to understand what happened with the land. And I also wanted to know how he acquired land”. This meant investigating and eventually correcting an established historical narrative. He spoke of contextualising his research, and explained “It was only by doing that research of not just this narrow, looking down onto [name] but what was around him” that led to a deeper understanding of the past.

John’s theory of history was an intense personalisation of the past. Of the painting he said “What I see is my great-uncle. What I see are his cows, and what I see in the background behind him is the shadow of the peppercorn trees the homestead where my great-grandfather was born. And when you start thinking about that, it’s, wow. And they lived in this house”. Here John illuminates a strong affective connection to this historical artefact. Unlike the other case studies subjects the main thrust of his research is centred on the people around the painting, as opposed to a structured and complete family tree.

John is a self-taught historical researcher but deftly draws upon various

methods to develop his family history. In an act of public pedagogy, where learning is seen as “the informal learning and ever educational experiences occurring within popular culture, popular media, and everyday life” (

Freishtat and Sandlin 2010, p. 503) he learned to research in and across multiple digital media platforms in addition to informal sites of education such as libraries, archives, museums, and art galleries. John confessed that he felt quite lost when commencing his genealogical journey and increased his skills by trial and error as time progressed. John spoke of using “many, many different guides” and countless websites. He referred to his local library which “has an excellent reference section” and speaking to historians at the archives.

John demonstrated flexibility in his research methods. He “let the painting tell the story” and started by comparing the geographical features of paintings by the same artist and then “looked at parish maps” which led to the use of conveyancing documents and a will. He was able to find out that his ancestor lived in “a two room hut” by exploring probate documents for their estates, which was supported by a “description in the coroner’s inquest”. Despite being self-taught in historical research, John showed agility in his application of a variety of research apparatuses. He used multiple sources of evidence and recognised the importance of historical context by explaining “I think what it’s taught me is that a lot of bad things happened back then. And you’ve got to realise that the values that we have now, aren’t the values that were around at that time. And you then have to start looking at things as to how they looked at things back then”.

The form of representation of John’s research is a widely distributed article outlining the history of an important Australian painting. There has been previous works written of the painting but as John explained “where are the supporting facts? And there weren’t any, it was just someone telling a story”. He continued by arguing that he “could’ve written a document which was literally tearing apart paragraph by paragraph, but that would have just ended up being an article which was us against them…which wouldn’t have proved anything”. He has given talks about his research at the National Art Gallery of Australia, and has located and met the descendents of the artist.

John’s family history research functioned to strengthen his connection with society, “hard to say how, but I find I can relate more to the history of the country”. Another function of his research was that his wider historical knowledge had intensified due to his family history research. His research also functioned to provide him with a deeper appreciation of the present, to understand the past and his historical consciousness was augmented by his historical investigations. This aligns with critical historical consciousness of Rüsen’s Typology, in that he is interested in exploring the past to verify historical accounts.

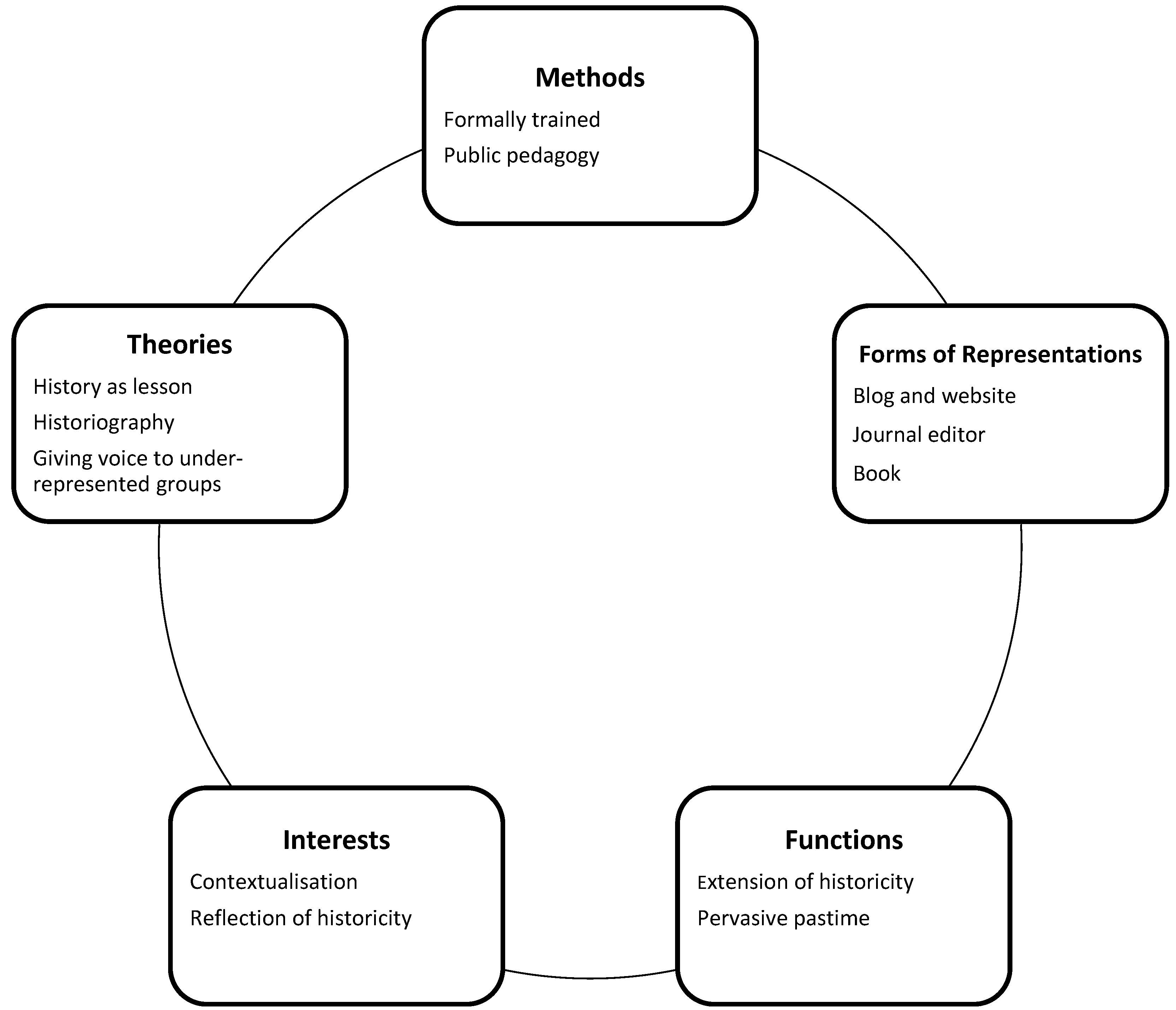

Figure 3.

Case study two in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

Figure 3.

Case study two in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

Jane originally from Victoria, but now resides in New South Wales, Australia. She identifies as Australian with an Anglo-Celtic ethnic cultural background. She is highly educated, having completed a postgraduate coursework degree, and she cites ‘education administration’ as her occupation. She has been undertaking her family history research for sixteen years and dedicates an average of twenty hours per week to her research. She has studied history as an academic subject at several levels from compulsory history at school to senior history at school and senior extension history at school and then onto university studies with a major in History.

When asked about her theories of history, Jane explained that “It means the study of everything that has contributed to who I am and what the society I live in is and it’s something I find very enjoyable to both produce and participate in”. For Jane the study of history is about locating herself in time and orientating her life in society. It also meant attention to the disciplinary aspects of historical inquiry, and was a passion to be simultaneously consumed and produced. When asked about her evolving understand of history as a discipline, Jane pointed to a shift from grand in focus to micro-historical narratives within historical scholarship. She acknowledged the recent shift to view history as multi-voiced, with the inclusion of previously marginal historical voices, such as social, women’s, indigenous and immigrant histories. Janes successfully locates herself firmly within the contemporary historical climate:

“I think that’s just been a natural trend in historical research for the last 40 years anyway, with the rise of indigenous history and religious history and ethnic history, and whatever else, all the people, all the different groups that have been left out of the more traditional big picture, important people, dates type history…It’s not so much that the history’s changed; it’s the way that people look at the history that’s changed.”

Jane further emphasised the importance of history to contemporary understandings and used a very relevant example, although this interview was held before the COVID Pandemic. She believes that as humans we benefit from learning the lessons of history. As such, Jane saw history as having a didactic purpose and she explains one impact on her historical consciousness from her exploration of history. Jane when searching a parish register for ancestral names when she happened upon a large number of children dying of measles:

[This is an] example of how history impacts on modern life is the anti-vaxers [anti-vaccinations] people of today. Because anyone that’s spent any time doing family history I think would just want to grab these people around the throat and throttle them…my solution with these people is to drag them to a town of a 19th century cemetery, and make them sit there and read out the gravestone of every kid under the age of five who died of these diseases, and make them do it until they change their mind.

Jane’s historical research methods are well developed. Jane is experienced in historical inquiry methodologies acquired through assorted encounters with history as an academic discipline as well as a wide range of learning opportunities focussed on family history research. She cites a wide range a university genealogy course, family history magazines, genealogical television programmes, personal practice, interaction with other family history researchers, participation in online communities, and family history how-to books.

Jane is an established family historian working in various forms of representation. Jane writes a newsletter about family history courses and events, is the editor of the historical society journal, maintains blog and website about family history research methods, and is involved in writing a book in collaboration with the university academics.

Following on from her school and university History studies, Jane has undertaken the role of teacher and mentor to many family and local history researchers. She runs research methodology courses and as such has taken on the role of public pedagogue. Jane is very involved in her historical society being the secretary and journal editor. She is currently working on two projects about World War One soldiers of her local area.

Jane expressed her frustration at the lack of archival organisation within the society, revealing she shouldered the responsibility of attempting to introduce orderliness to the documents and artefacts collected by the society over time.

It’s the regular story of most historical societies; it’s a very ageing demographic in membership. It’s a small society anyway, and it’s getting smaller as people basically die, and it’s very hard to attract new members.

Jane’s leisure activities further highlight her interest in history. She reported that as well as her local historical society work, she undertakes a wide-ranging interest in public history activities such as viewing historical movies and documentaries on television, reading historical non-fiction books, regularly attending museums. She is interested in her family research in its historical context and has a deep understanding of how history influences the present. She sees her family history research as confirmation of her historicity, meaning authenticity based on verifiable evidence.

Jane’s historical consciousness has a strong influence on her values, who she is, and how she perceives herself. Her historical activities and practices function as a reflection of her historical ideologies, and she actively produces historical representations and seeks scholarship to support and augment her historical experiences in their totality. Janes’ interest in history is all-pervasive as it encompasses, and permeates, all aspects of her life as she claims, “Oh if I win lotto, my life is going to be going from archive to archive…just jumping into the documents. I could do that for weeks on end, that’s not a problem.” Jane’s historical consciousness is nuanced and sophisticated and with an understanding that time and values systems change over time, placing her at genetic historical consciousness in Rüsen’s Typology.

Figure 4.

Case study three in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

Figure 4.

Case study three in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

Lucy is from Sydney, New South Wales. She is currently completing her PhD in law, and she studied history in high school. She commenced her family history research when she was 13, and she is not a member of a historical society. She has no plans to publish her family history research at this time. Lucy cited her grandfather as the catalyst for her interest in family history research. She explained that he “had started up his family tree and so he would tell us, my brothers and I, some family stories. And he passed on the family tree to me because he thought I might be interested and that’s what sort of started it off”. As time progressed, her interest became a desire “to get a fuller picture of where my family came from”, which culminated in a comprehensive family tree which is the form of representation of her research.

Lucy is also self-taught in historical research methods. She told that “it was really trial and error and Googling…because I think back when I started there wasn’t really a great deal of things online that were freely available as there are now”. She spoke of how her research methods grew over time, and of the collegiality of the online genealogical community which “helped out”. She told how she cross-referencing her sources, and ensured their accuracy through a “process of elimination”. Lucy further revealed that she contextualised her findings within the broader historical landscape by initially thinking about “the legal connections” and cited the Matrimonial Clauses Act (1858) and Lord Hardwicke’s Act (1753), and of the methods she used to break through ‘brick walls’.

Antithetically to other case studies in this paper, Lucy’s family history research did not

function to create an affective relationship to her family past. She claimed her research has not impacted on her life, and she explicitly told of an impassive emotional connection to her ancestral past, despite her interest. She explained that “I could say I don’t get horrified when I read things. Like you know in those

Who Do You Think You Are? programmes you find the celebrities crying over small things about what their ancestor’s gone through? I don’t get emotionally attached like that”. She explained that temporal distance, defined as “a position of detached observation made possible by the passage of time” (

Phillips 2011, p. 11) was the reason why she could not connect with her ancestors by stating “I try to take an objective view towards what I look at because there is a distance between us. I don’t feel completely connected with them, but I’m interested in finding out about them”.

Lucy’s research, however, did function to provide her with knowledge of the past and connect her to an estranged part of her family. She explained that “my parents divorced when I was very young, so I didn’t have much contact with my Dad’s family…and it was really trying to bridge that gap”. Another function of her research was to provide explanation as a means of understanding the perspectives of the people of the past, and to help to make sense of and explain their actions in both the past and the present. She revealed “And he was from a very poor Irish family and he used to walk to school barefoot and so it sort of gives you an impression of why he might have become a hardened person, because of his upbringing and the way he was treated”.

Lucy’s theories of history were well-defined, and her historical consciousness is best described in Rüsen’s Typology as genetic. Lucy understands the constructed nature of history and spoke of the invisibility of women in older historical accounts and argued “it does disappoint me when I can’t find out anything about some of my female convicts, because they’re as much of my history as the men”. She theorised history as a pedagogical tool in which the past “helps us reflect on what we should be doing in the present or the future to see what might have worked or might not have worked in the past, and how that might have influenced now, or what we should do in the future. It’s a reflective exercise and you like to see what people in the past did, or events that happened in the past and how that’s shaped us”. Again, this reasoning is evidence of Lucy’s high-level historical consciousness, as the past is used to understanding the present and considers its impact on the future.

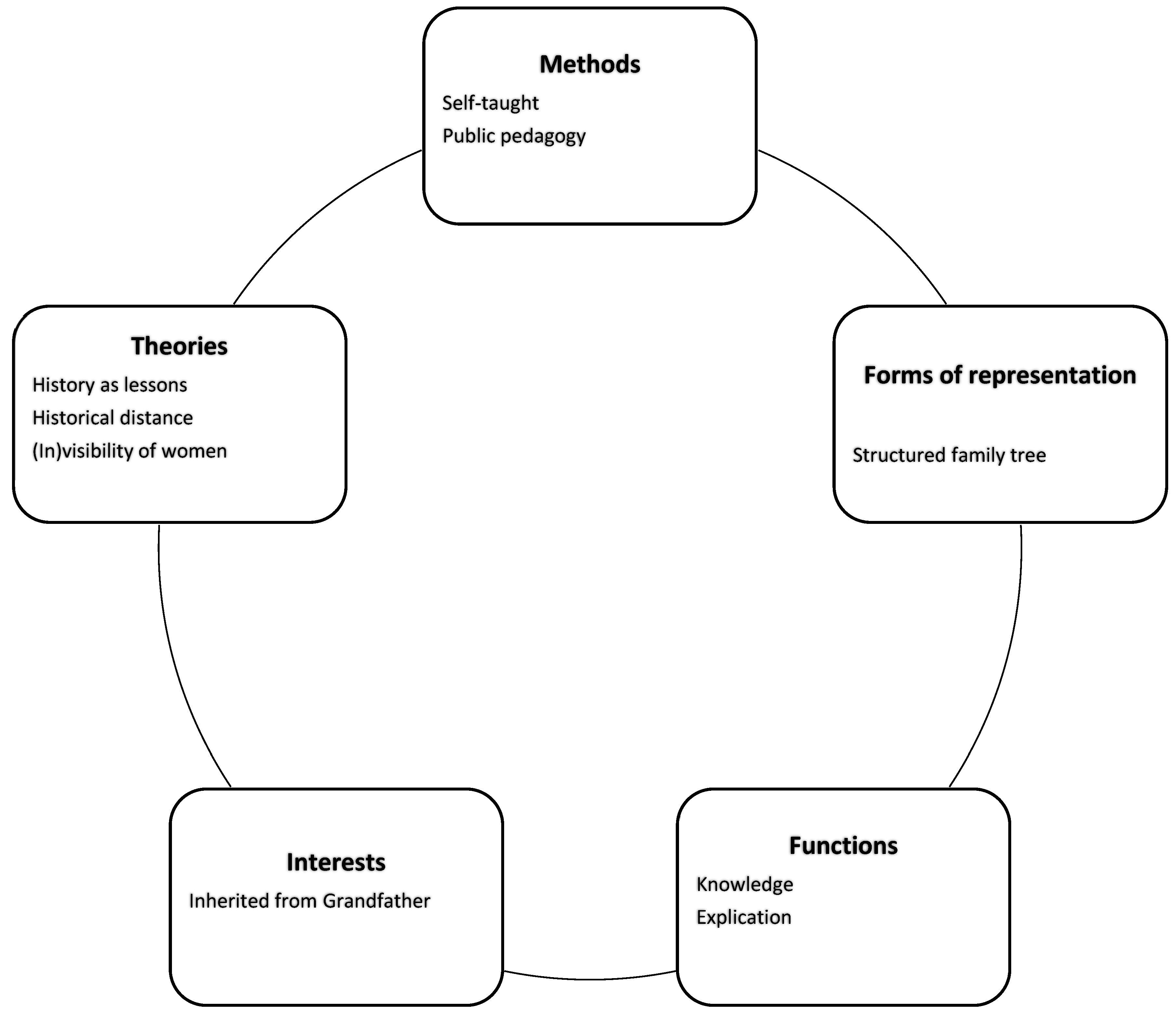

Figure 5.

Case study four in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

Figure 5.

Case study four in alignment with

Rüsen’s (

1993) Disciplinary Matrix.

Claire is from Queensland, Australia. She identifies as Australian, with European ethnic and/or cultural background. She is highly educated having completed a coursework Masters degree, and is a science teacher in a secondary high school where she is Head of her Department. Claire is a very experienced family history researcher having commenced her familial research in 1984 and dedicates a maximum of 20 h per week on her family history research.

Claire is interested in history in many forms and is prompted by curiosity and a search for “truth.” She views historical movies and documentaries on television, and she reads historical non-fiction books. “I’m one of those people who doesn’t read fiction, so it’s either history or autobiographies, or science books or something”. Claire participated at a local historical society and explained that she was motivated by her research quest. “I just go out there if I wanna do research”. She had not taken on special offices or duties within the society, but expressed an interest in doing so when she retires. As to forms of representation of her work, Claire wrote two articles for the society that had been published in their newsletter. Her methods of historical research are mainly self-taught. In the beginning, her research journey was ad hoc in its approach, and when interviewed and asked how she learned to ‘do’ her research, she stated:

It was a bit hard when I started…because there was nothing online, there was no such thing as the internet. I used to go out to the Mormons, and they were very helpful, and I was using German records a lot, and they would get the film in and I’d sit there and read it painstakingly. Oh, and we used to go to the archives…it was very, very time consuming.”

Over the years Claire has developed advanced research skills in virtual and real contexts and has acquired the skills to locate, select, apply, and corroborate various and diverse historical sources.

I try to build up a picture of the person’s life and see how it fits together, and usually you can find where the discrepancy is. You’ve gotta look at them in context, and you’ve gotta look at the bigger picture…you can’t sometimes just go to what you’re tryin’ to find out…if it doesn’t fit in, then it’s not right is it?

An interesting revelation to emerge in the interview was that Claire had travelled internationally to Germany and Scotland to conduct her family history research. The literature refers to this as genealogical tourism (

Santos and Yan 2009). With regard to Scotland, Claire talked of how her ancestors were cleared from the Highlands and “they were told to become fishermen, and it’s such…we visited up there and it’s such barren sort of awful country, it’d be very hard to exist”. In Scotland, she visited the village from which her ancestors came, and saw the house where they lived, which was, in her words, “quite thrilling”. In Germany, Claire took many of the photographs featured in her book and it was this German family that was the basis of her book—another

form of representation which had some modest success commercially.

When asked about her theories of history, Claire defined history as “events that are past—usually long past”. Probed further in the interview about her interest in history more generally, she replied that “I think you can learn a lot from it really”. Locating her interest in history to a familial trait, she mused that “I s’pose my mother was always interested in history, I might get it from her. I just think you learn a lot from history, and it helps you understand the world around you a lot better”. As an example, she divulged that she had just finished reading a book about New Guinea during the Second World War. Her reason for doing so was an attempt to understand and contextualise her father’s wartime experience as he was stationed there during the war. She told of how he always hated the Japanese, and “he went to his grave hating them”.

When asked about her

theories of history, Claire acknowledged that her family history research allowed her to see the importance of contextualisation:

I don’t think you can research people without looking at the history behind it…because it affects them so much, doesn’t it? Everyday life and what they did and why they did it…that’s probably why I got interested in history, trying to put them into context.

Claire’s contextualisation of her ancestors into their wider political and social milieus served an important function in her understanding of herself as an historical being. She located her ancestors in place and time, and sought to comprehend the actions and motives of people of the past through exploring the social/political/economic elements of the time period being researched. This process augmented her historical understanding and has led Claire to a greater understanding of her own life, and who she is as a person. While not being formally schooled in the conceptual underpinnings of the history discipline, Claire reveals a sophisticated approach to her research and a well-developed historical consciousness which can be aligned to genetic in Rüsen’s Typology.