1. Introduction

Does the Mexican nation have one or many genealogies? What place does genealogy have as an input in building something in common? The modern world is organized into nation states, but none of them can, in the twenty-first century, boast of being homogeneous in language and culture. In Mexico, it is the state that has built the nation. To understand this long and intense process of construction that began in the 19th century and continues to the present day, it is necessary to look at a typology that allows me to identify three types of nationalism. (

Gutiérrez Chong 2013). The first type is the nationalism of independence and the formation of the sovereign state (19th to 20th centuries). Its main features are: wars of independence (1810) and the end of colonial rule (1820), territorial disputes and the demarcation of sovereign territory, the election of popularly elected governments, the defense of the nation and territory against invasion and aggression by foreign nations, and the writing of different projects of a constitution. The second type of nationalism is nation-building (20th century). The state and its institutions play a significant role in making the nation, following an integrationist policy. Among its main features are the nationalization of the economy, the homogenization of culture and linguistic unification, a standardized schooling system, civic culture, infrastructure and communication, the assimilation of Indigenous peoples and other minorities, and the construction and massive inculcation of national identity. The third type of nationalism is the era of multiculturalism and the recognition of diversity (21st century). In this, one finds the following: economic neoliberalism, Indigenous uprisings and ethnic resurgences, political activism around awareness of ethnic identity and sexual diversities, Afro-descendancy, gender and environmental protection, the democratization of the state, a culture of human rights, and legislation on the right to free determination and the autonomy of Indigenous peoples.

This article takes into account these three types of nationalism: the anti-colonial struggles that give rise to the state, the state that builds the nation, and the cultural diversity that challenges the homogeneity of the nation built by the state. A nation is a community of people with their own historical and cultural attributes and is rooted in a territory. The nation is not something natural, therefore, attachment, belonging, and loyalty must be inculcated among the citizenship that is rooted in a territory. A nation assumes that its members share “something in common”, exercise social cohesion, recognize themselves around an identity, and work out cultural and political sovereignty. In the construction of any nation, cultural and linguistic homogeneity has been imposed at the expense of the diversity and plurality of existing cultures and languages. This homogenization is not forever; on the contrary, access to education as a condition for the modernity of the state has promoted the visibility and activism of the unrecognized Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants who have sought for their inclusion in the course of the twenty-first century.

Nation-building by the state began, according to the most verifiable records, in the first decades of the twentieth century in Mexico, with the implementation of standardized, secular, and free education (

Booth 1941;

Sierra 1948;

Nash 1965;

Vázquez de Knauth 1970;

Brooke and Oxenham 1980;

Solana et al. 1982). Education, which has been the transmission belt of several generations from the 1960s to the present, is a set of information that deals with the past, the territory, the people, the cultures, and so on. Official education has contributed enormously to delimiting the contents of national identity, Mexicanity, and its massive distribution.

This article seeks to critically rethink the myth of the mestizo in its more than 500 years of existence. The myth of the mestizo is well known to have many angles of analysis. It is worth clarifying that the article does not make a history of five centuries nor will it include the vast iconography, biology, anthropology, archaeology, and even genetics that have driven the study of the Mexican mestizo (

Basave Benítez 1992;

Florescano 1987;

Gruzinski 1993;

Knight 1990;

Lafaye 1985;

Marshall 1939). More recently, the historian

Federico Navarrete (

2016) presented valuable arguments about mestizaje as the basis of Mexican racism, since mestizo and white populations often discriminate against and despise the Indian population. However, this article shows that, before becoming a racist ideology, mestizaje was a myth that served to provide a nation with a common origin. The path that this article will take begins with a review of the meaning of the myth, its influence on society and the culture of the nation, and how the myth is perceived by mestizos and Indigenous peoples. To understand the construction of the Mexican nation, one must consider its Indigenous and European parts, always in contradiction, tension, collaboration, or rapprochement. Thus, the article will address how Indigenous ethnicity becomes part of the symbolic richness of national identity, as well as the integrationist nation-building strategy of the 20th century ideology of the “cosmic race”. It will continue with the explanation of the nationalist aesthetic that helped to spread the mestizo content in popular consumption calendars and the Gellnerian tradition of the standardized school (

Gellner 1983). While the myth of the mestizo has begun to face various criticisms, the final part will refer to the validity of the myths of origin or genealogies of Indigenous peoples by weighing the results of qualitative interviews and a survey that sought to measure how the mestizo is perceived among Indigenous people.

2. The Ethnic Past and the Origin of Nations

With much vehemence throughout his fruitful intellectual life, Anthony D. Smith (1939–2016) managed to convince that a nation exists thanks to its powerful ethnocentrism (

Smith 1984,

1985,

1986). This ethnocentrism collects and embodies substantial information that determines the authenticity, originality, and genuineness of one nation in relation to another. Coming to such a collective awareness of cultural or linguistic distinctiveness is not easy or trivial. Ethnocentrism is a construction that involves symbolism and fiction, thus, it is the work of intellectuals, nationalists, antiquarians, leaders, or communicators. In each ethnicity there are mythical qualities, states Anthony Smith, no matter whether the ethnicity is a majority or minority, civic or territorial, because no nation can emerge and maintain itself without an ethnic or ideological “core”, from which the central ideas that ignite and encourage nationalisms are derived, that is, movements, ideologies, or doctrines that seek the “ideal of independence” (

Smith 1986). The ethnic nucleus or ethnocentrism, or mythomoteur, is nourished by myths of ancestry, lineage, heroism, and genealogies. It is the construction of a narrative that points to the origin of how a nation or ethnic group emerged. Every social group has an origin. An origin that is exalted, glorified, and admired because it marks the exceptional beginning of a community.

The national identity built by the Mexican state rests on two very effective myths: Aztecism and mestizaje (miscegenation). So as not to leave a void, since I will only deal with the narrative of mestizaje, I will say that Aztecism, an ideology praising antiquity, refers to the foundation of Mexico-Tenochtitlan (1325), a spectacular metropolis that existed before the European arrival to the American continent and the Spanish colonization that would transform the lives of millions of Indigenous people forever (

León-Portilla 1987). However, Aztecism is the idealized, monumental, and glorious past of the Mexica ancestors of the Mexicans, and the ancient settlers are known as Mexica or Azteca, evidenced in numerous archaeological sites in the Valley of Mexico. The Aztec symbol of the foundation of the Mexican capital is found on the currency, it is used only by the executive, and is the national coat of arms.

Now, while mestizaje is an official narrative of national integration, I will first define its most important historical traits and then refer to the dissemination of the narrative as a nation-building strategy.

As a historical fact, Indigenous peoples and mestizos did not exist before 1492

1. Both are the result of a colonial domination that lasted more than 300 years, if we consider that the official date of the independence and sovereignty of Mexico is from 1810. Before the middle of the fifteenth century, there existed in the vast territory of what we now know as Mesoamerica

2, which extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica, a plurality of people, organized under their own logics, experiences, knowledge, languages, realities, and subjectivities, to summarize a vast and profound social and cultural complexity. Approximately twenty million original inhabitants knew how to live, develop, and reproduce with their joys, sorrows, and fears, the latter perhaps very present in their daily and symbolic lives, but this is how life passed with one notable characteristic: without contact with the culture, language, and religion of Europe, specifically of the Iberian peninsula and its dominant institution, the Spanish Catholic crown (

Lockhart 1992). During colonial domination, these hundreds of groups of people with their own ethno-names, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, and so on, were diluted under the generic name of Indians, or Indigenous (

indios). The starting point for the biological and cultural construction of the mestizo was the colony, as I shall explain next.

Every process of domination involves sexual harassment and assault. The Spaniards who arrived in the New World came, initially, without women, and of course, there are no records of how soon contacts between outsiders and natives occurred. According to the narrative of the Spanish soldier and chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo (

Díaz del Castillo 1978), the fact remains that the sexual, cultural, and symbolic contact that resulted in relations of domination and power has been epitomized in the conqueror of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Hernán Cortés, and a Náhua woman, who due to different internal circumstances was bilingual, speaking her native language, Náhuatl, and the Maya language. That she had been a Maya speaker facilitated communication with Hernán Cortés, since, in an earlier expedition, a Spanish soldier named Jerónimo de Aguilar was stranded in the Yucatán Peninsula, where he learned the language. She is known as Malintzin or the Malinche. She was accused of being a traitor because her language skills facilitated the conquest of Mexico, and because Octavio Paz (1914–1998), 1990 literature Nobel prize laureate, referred to her as a key piece of the Mexican identity tragedy (

Paz 1959,

1987). The Malinche is a fascinating character, real or invented (

Glantz 1994), but she has served to legitimize what I am explaining here, the narrative of the origin of the nascent Mexican nation. Malintzin or the Malinche, the original progenitor, and Hernán Cortes, the conqueror, who subdues and dominates, in an imaginary union, create as an almost childlike result, the progeny, neither Indian nor Spanish, that was born in the New World, the New Spain. That is how simple the narrative of the Mexican nation’s origin is.

A Spanish conqueror and an Indigenous woman form the founding couple of the Mexican nation, thus forming the myth of the mestizaje that will serve to guide the construction of the nation after the Mexican revolution of 1910. Now is the time to consider the genealogy of the nation, taking into account the fundamental fact of the great diversity of Indigenous peoples who did not become mestizos because of interracial contact. In fact, the interracial mestizaje towards the end of the seventeenth century increased (

Israel 1975), involving Spaniards, Indians, and Blacks, resulting in sixteen “racial combinations”, which form the caste colonial system. As

Lomnitz-Adler (1992) has shown, these colonial “racial combinations” were diluted into the national mestizo race. So, what can be done for Indigenous people who are part of the nation under construction? What needs to be done to integrate Indigenous peoples into the family of the founding couple?

Indigenous peoples during the twentieth century were equated with rural backwardness, reduced to poverty, a lack of development, and obstacles to progress due to the persistence of their original cultures and languages. Since 1940, a public policy, known as indigenism, has been implemented so that Indigenous people adopt mestizaje as a national integration strategy (

Caso 1962). The integrationist strategy planning was carried out with scientific methods, guided by the anthropology of those years, to promote the assimilation of the Indigenous people by adopting Mexicanity, which consisted of leaving aside their languages and cultures and becoming Spanish-speakers, leaving behind “ancestral” customs, adopting “corrective hygiene”, and parting with their lands to facilitate economic development, to mention a few examples (

Aguirre Beltrán 1975). However, as this article will show later, mestizaje and development did not lead to the disappearance of the Indigenous people.

The mestizaje of the post-revolutionary period also meant the search for and delimitation of the identity of the nation

3. Every nation seeks to distinguish itself from another by virtue of its originality and authenticity. Its ethnocentrism must be original, genuine, and authentic for its legitimacy to be flawless and widely recognized. There are no guidelines to forge an ethnocentrism. The ethnocentrism built based on mestizaje is a mixture mainly of many Indigenous groups and peoples from Spain. Therefore, the Mexican case is defined by the coexistence of several native ethnicities and a foreign one to build an ethnocentrism of national culture.

To understand how this process took place, it is useful to resort to the famous dichotomy

4 of a careful observer of the Indigenous world of the time, Fernando Benítez (1912–2000), and the distant difference that separates the “dead Indian” from the “living Indian” (

Benítez 1968). The first is the memory of a wondrous past worthy of admiration because it refers to the monumental archaeology that has extolled the state in the construction of national identity. The “dead Indian” is found in museums and archaeological sites. The “living Indian” is the daily experience of individuals or families living in poverty, those who beg in the streets, those who hinder development, those who migrate to the cities, and those who work in domesticity or in the hardest and lowest paid jobs. The “living Indians” have been the object of study in different schools of anthropology because, in addition to investigating how their integration has occurred, anthropology and ethnography have also sought how to prevent them from losing their cultures and languages, since these contribute to the originality and authenticity that I am explaining. The Indigenous hands produce art in many ways, making textiles, embroidery, basketry, and ceramics. The deep beliefs of these groups bring rituals, symbols, dances, prayers, songs, and music. They preserve the traditions of their peoples, communities, deities, saints, life cycles, protection, and care of nature. There is no doubt about the contributions of the “living Indians” to national culture, to the cultural heritage of humanity and to tourism. Indeed, the contribution of the living Indigenous to the ethnocentrism of the nation generates more than one contradiction. The Indigenous, dead or alive, the first admired, the last despised, are necessary for the originality of the nation.

3. The Cosmic Race

Mestizaje is the result of the racial and cultural fusion between the old and the new continents. Here, it is important to go back chronologically to explain why the Mexican Creoles appropriated the native peoples, the Indigenous. Creoles born in the new world, although they shared with the Spaniards language, descent, and Catholicism, occupied low positions and were subordinated in ecclesial and bureaucratic hierarchies. To justify their colonial liberation, the Mexican Creoles began the construction of an identity that would make them different from the Peninsulars. The Creole–Peninsular rivalry was caused by the place of birth, and this was a cause of the deep inequalities between them

5. If America was imperfect and weak, according to the French naturalism of the 18th century, the Creoles saw the opportunity to dignify what was original in the new continent. Thus, the themes of Creole patriotism were the admiration of the pre-Hispanic past, the recurrence of nativism, the adoption of the Marian symbol, and the Virgin of Guadalupe (

Brading 1985). There were promising conditions for the appropriation by the Creoles of the nativist symbolism of Mexico; the Indians were controlled politically but possessed great symbolic wealth. The participation of the Mexican Creole elite with respect to the delimitation of their identity began in 1731 with the Jesuit, Francisco José Clavijero, and the Dominican, Fray Servando Teresa de Mier, among others. The Creoles appropriated Indian symbolism to justify their political separation from Spain. But the mestizo, during the colony and after independence, was regarded as a bastard, repudiated by the Indians and the Creoles.

The rehabilitation and dissemination of the new national hero, the mestizo, occupied a prominent place in the decade following the Mexican Revolution of 1910. What happened for the mestizo-bastard to become one of the most powerful symbols of integrative nationalism? The answer has to be found in the role of the intellectuals, following an explanatory guideline by Anthony

Smith (

1991), because they would have the clarity to face the dilemma of how to seek authenticity and originality, how to respect it, how to defend it, and how to dignify it. Scholars of nationalism give a prominent place to intellectuals because they often create powerful symbols to attract the masses to a political project (

Hutchinson 1987;

Breuilly 1982;

Guibernau 2000), using their imagination and experience to endow the nation with its cultural and emotional contours. As explained in the previous paragraph, the Creole–Peninsular rivalry made the intellectual elite of the new world retake from America the richness of its dignity. As it is known, in 1983, Benedict Anderson resorted to the example of the first novel written in Latin America,

El Periquillo Sarniento (

The Itching Parrot), to show how the “birth of the

imagined community of a nation can best be seen…” (

Benedict [1983] 1990, 6th ed., p. 30; emphasis added;

Calhoun 2016). The novel, written in 1816 by a Mexican Creole, José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi, is an extensive narrative in prose, with a movement of characters in diverse environments and times, and it accounts for the colonial transition to the national stage and narrates the forms of Spanish administration. It is a portrait that informs about the nascent Mexican consciousness. In 1998, Smith wrote a critique of Anderson, desisting from seeing the nation as a discourse, a narrative, a text. The nation is real, its members live, die, suffer, are everyday life (

Smith 1998). It is possible to observe that these authors are referring to different situations: Anderson’s imagined community refers to the moment of the origin of a national community, the social and cultural description that a Creole intellectual captures in the genre of the novel, and Smith refers to the myths, legends, and symbols of the real community, which also count as narratives.

6 If the mestizos began to dominate the Indians numerically, and the mestizos could never belong to the Creole circle of the Spanish Americans, they would have to be rehabilitated. José Vasconcelos (1882–1959) was one of several intellectuals (Alfonso Reyes, Justo Sierra, Manuel Gamio, Antonio Caso) who understood the moment for their rehabilitation and take-off, and for this reason he constructed an ideology, a set of non-scientific ideas, to justify the mestizo launching (

Vasconcelos 1986). Mexicans in the racial terms of the time, which were divided by color, were not black, nor white, nor yellow, they were “bronze color”, a color more adjusted to the racial mixture initiated in the colonial period

7. More fortunate was the motto: the bronze race, and even more so, the cosmic race. The universal characteristics of the cosmic race implied not only having their residence in Mexican territory but also extending to the whole of Latin America. José Vasconcelos´s national project was controversial, he did an enormous educational work and dreamed of a literate nation, he understood how to give strength to the weight of mestizaje even if it was a utopia. He was a passionate intellectual, in love with Latin America, who believed that the gene pool of the inhabitants of the continent was not a weakness but its greatness. It is very important to say that this mestizaje was seeking to fuse the Indigenous peoples with the cosmic race. The mestizo was rehabilitated as a national axis to generate the integration of the Indigenous populations. Hence, the acceptance of the mestizo was initiated and valued, and philosophers, political scientists, anthropologists, sociologists, ethnologists, and artists would focus their efforts and contributions on dignifying the new hero of the twentieth-century nation.

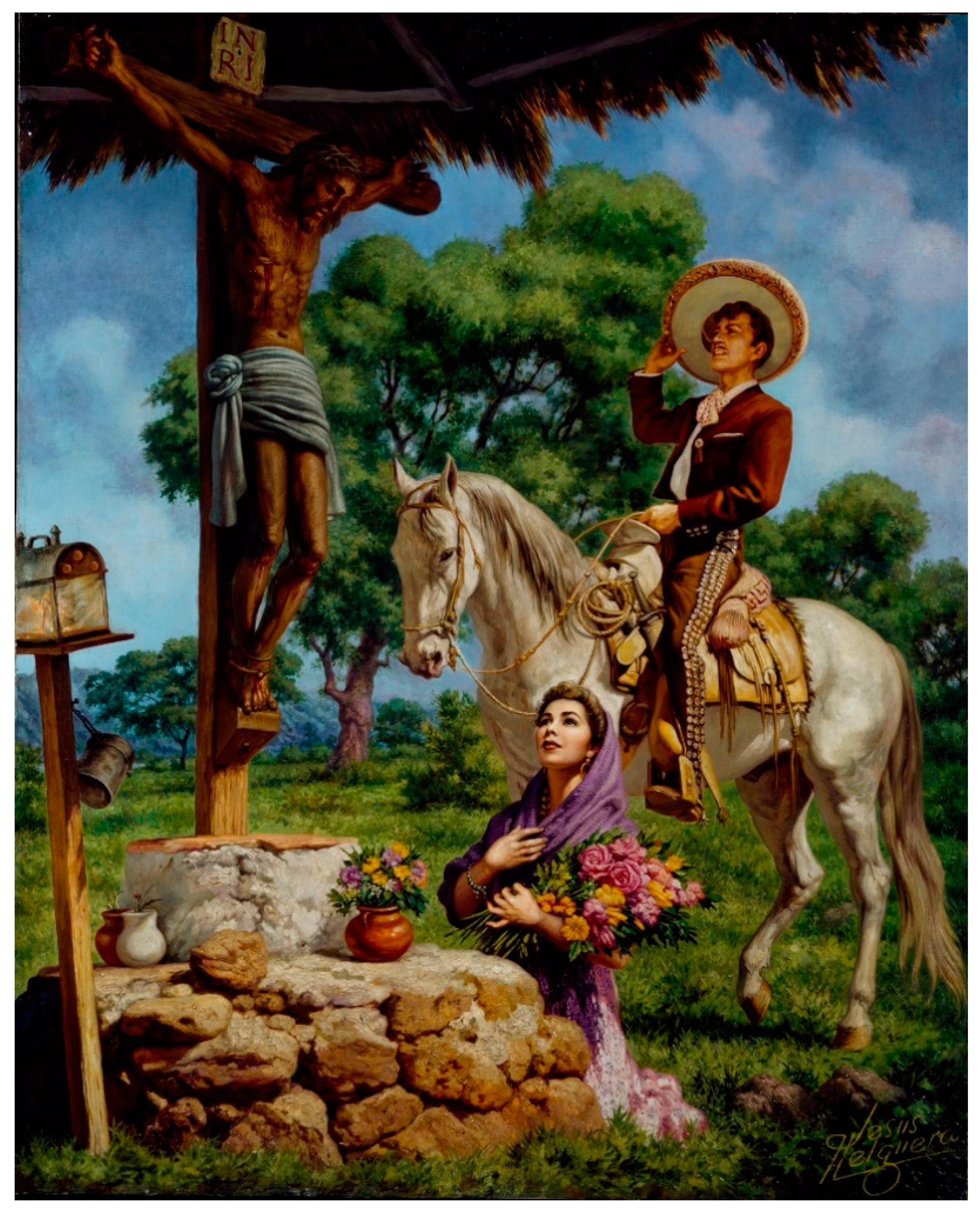

8 4. The Calendars

To give a firm example of how the rehabilitated mestizo was spread across the Mexican society of the twentieth century, let us look at the iconography that decorated calendars (

Museo 2000). Yes, it is those printed calendars, derived from chromolithography, that were given away in shops, that hung on the walls of houses and businesses and served to count time. Another topic for Anderson was counting time and massive printing. There were several painters who made a singular contribution to the nationalist aesthetic of the calendar drawings, and Jesús de la Helguera from Chihuahua was one of them. According to

Elia Espinosa (

2004), who has studied his work, there was in the “idealization of the Indian, of the Mexican countryside that he embodies with bodies and faces of typified beauty” (p. 14).

Here, I am going to make a necessary parenthesis to show that women have had a lot to do with the construction of the narrative of mestizaje and with its massive diffusion. First, let us not forget that the mestizaje is a history of asymmetry and domination, so that the winner will always be a foreign, superior, conquering, adventurous, and reluctant man, while the woman will be represented as native, aboriginal, passive, sublime. Second, the drawings on the calendars portray women of rural, idealized, and sensual characteristics, equally dominated and in a state of passivity. The environment which portrays a farm or a rural village, an idealized home, and the families that procreate these mestizos is very revealing, as seen in the

Figure 1.

The illustrations on these calendars allow for exaggerations and idealizations about landscapes, legends, myths, environments, and peoples. Jesús de la Helguera possessed a mixture of stridency, with which he included the poor, but also the growing middle class, using a combination of styles in adapting European Mannerist (late Renaissance art style), Baroque, and Neoclassical painting (

Espinosa 2004, p. 14). The drawings of the calendars become vehicles for transmitting the socialization of the mestizo, hence fulfilling an objective of national identity.

The archetypal Mexican couple massively socialized in these calendars shows the symbols of the feminine and masculine of the nationalist aesthetic of popular consumption. Thus, while the feminine represents, mainly, the ideal of the mestizo woman, smiling, with soft features and manners, the masculine figures symbolize physical strength, virility, and heroism, characteristics that correspond to practices and behaviors of the patriarchal man (

McClintock 1995). The objective of these images is to delimit the types of unions and their descendants that will make possible the construction and reproduction of the nation. As it is known, nationalisms have cultural limits, remembering the multi-quoted “imagined community” of

Benedict Anderson ([1983] 1990), which is finite, limited, and sovereign. Another way of saying it is: the identity of a nation and its repertoire of symbolic resources only concern and give meaning to that community of people and no other.

5. The Gellnerian School

The standardized school has played an outstanding role in the massive inculcation of the origin of Mexican descent. In this explanation, the modernist theory of Ernst Gellner (1925–1995) makes sense, since he visualized an interconnection of components: industrialization, the social division of labor, standardized education, and occupational mobility (

Gellner 1983). Since the last years of the nineteenth century, the Mexican state has been building a great monopoly on public education according to the Gellnerian point of view. This monopoly has sought to absorb local loyalties and replace them with civic obligations and duties to the centralized state. This article will not dwell on the history of this monopoly on education, nor on its functions, nor on its contradictions. But it will focus on identifying the great resource of such a monopoly, primary school textbooks, as they contain very precise lessons about the mestizaje and the origin of Mexicans. This aspect complements the previous section on the popular consumption of calendars and the nationalist aesthetic. Since 1880, there have been textbooks for primary schools, but they have had different points of view and have not been coordinated. A textbook from that year recalls: “The republics are sustained and prospered by the patriotism of their children and no one makes sacrifices for what they do not know” (

Vázquez de Knauth 1970, p. 64). Another important effort to learn about the history of textbooks is Mary Kay

Vaughan’s (

2001) study of rural policy and the mobilization and inclusion of rural populations from the 1940s to the 1950s. However, the textbooks, designed to unify the sense of and belonging to national identity, have existed since 1959 (“Decreto Presidencial de la Comisión Nacional de Libros de Texto Gratuitos”). Their designs and contents have certainly undergone changes of various kinds. However, the purpose of the book collection continues: to forge unity among Mexicans, create citizens, and prepare a workforce that responds to economic development. This narrative continues to the current edition (

Catálogo Digital de Libros de Texto Gratuitos, Ciclo Escolar 2019–2020).

The content of the school textbooks is based on research produced by renowned intellectuals and historians. How can young readers understand the conquest of Mexico by the Spanish and a 300-year domination? The episode revolves around the destruction of Mexico-Tenochtitlan during the Spanish conquest in 1521; hence, once again, the role of the Mexicas or Aztecs is highlighted. As the Conquest is linked to the destruction of the native society, the sense of the heroic resistance of the Mexica is emphasized and the style of the narration is dramatized. Since ancient times, Mexico has been a mosaic of distinct groups, and this linguistic and ethnic diversity was irreparably altered during the colonial period. The vision embodied in the school textbook of this ethnic and racial mix designates the process as “The meeting of two peoples” or “A new culture is born”. This section contains mythical allusions surrounded by popular fantasy and intellectual speculation, but, as the textbook reveals, the invention of the mestizaje narrative remains a powerful symbol of integration. According to the textbooks, the traumatic effects of the Conquest, the arrival of unknown diseases, and the onset of pandemics, as well as the introduction of new economic activities, resulted in a drastic reduction in the native population: the colonizers replaced the Indigenous labor force with slaves from Africa. The lesson then reads: “Very soon there were three groups of people in New Spain: Spaniards, Indians and Blacks. These groups mixed with each other until they formed families composed of people of different races”. Such racial encounters must be viewed from the perspective of imbuing a myth of descent. If almost the entire population has mixed ancestry, it is possible to shape the perception that Mexicans are one “family”. From this simplistic point of view, they are neither Indians nor Europeans, but the compatible and benevolent result of both, a notion that ideologically resolves the difficulty of granting equality of descent to groups with cultural and racial diversity. The official point of view in the texts is very clear: “[...] men and women, Indigenous and Spanish were also mixed and from them were born the mestizo peoples, of whom we Mexicans of today are descendants” (quoted by (

Gutiérrez Chong 1999)).

6. Myths of Descent or Genealogies of Indigenous People

The genealogy of mestizaje as a national axis has already been explained. It is now time to put to the test how mixed races and cultural assimilation are received among the Indigenous people. To this end, the interviews reproduced below are evidence of the dynamics of the narrative, on the one hand, that the interviewees reject, the national myth, while on the other, the informants say that many of them hold their own ethnic narratives. Such information preserves much of its originality and validity because there are no recent studies showing Indigenous criticism of mestizaje

9.

Most of the cultures of contemporary Mexico have their own myths of origin that can be found in an ancestral past (

Weitlaner 1977;

Scheffler 1983;

Taube 1993). For example, the Mayas of the Yucatán Peninsula recall their origin in the book of Chilam Balam, the Mixtecs of Oaxaca know the narrative that they emerged from the trunk of the Apoala tree, other groups in the center refer to the fact that their origin began when they came out of caves, which emulated their mother’s wombs, and the Zapotec, have the belief that they are descendants of the clouds.

The interviews were aimed at Indigenous professionals and students of higher education. The selection of these informants corresponds to the fact that they are involved in issues of education, culture, and language, that they have independence of thought, are leaders, have editorial projects, and are interested in rehabilitating and disseminating their culture. They are bilingual. The composition of this elite of educated Indigenous people interviewed in 1986 was formed by 10 in-depth interviews with Indigenous professionals from different ethnic groups, and 60 questionnaires applied to two groups of students. From this date, the enrolment for Indigenous students will certainly have increased, although Indigenous professionals and intellectuals remain a minority, but they have not disappeared (

Gutiérrez Chong 1999, pp. 27, 31).

Responses and opinions on the experience of mestizaje are predominantly negative. It has been some time since these interviews were conducted, however, the strength of the responses has not observed significant changes in indigenous perception, if we take into account that the myth of common origin, mestizaje, led to the specificity of the racist ideology in Mexico that emphasizes mestizo at the expense of the indigenous. The following is a selection of excerpts from interviews with Indigenous professionals regarding the following questions (

Gutiérrez Chong 1999, pp. 153–56):

What is your opinion on mestizaje? Do you agree with the view that all Indians have to become assimilated with the mestizos?

Racially and biologically we are mestizos, but this is not the problem. The real problem is that the real Indian is not accepted, in order to have a normal life, the Indian has to be assimilated. (Maya, anthropologist)

The mestizos are bastards to us. The mestizaje is only ideology. (Tsotsil, anthropologist)

I disagree with mestizaje because our Indigenous heritage teaches us to appreciate who we are and not reject who we are. (Tseltal, linguist)

How can it occur to an Indian, to believe that he is descended from a Spaniard, is absurd! The mestizo culture expresses itself with superiority with respect to the Indigenous. (Mixteco, sociologist)

The mestizaje is a creation of the state to integrate the nation, the state insists that we are all mestizos. (Nahua, historian)

Next, I will show the opinions of Indigenous students, postgraduates, and graduates regarding the question: what is mestizaje for you? (p. 59)

It does not make any contribution. It appropriates the Indigenous to make a fusion with the dominant culture.

It proposes cultural and linguistic unification.

It’s a kind of racism.

It’s a belief in cultural superiority.

It’s an ideology that discriminates against Indigenous people.

It is an imposition to learn the Spanish language.

The myth of mestizaje was categorically rejected by Indigenous professionals and students. The mestizaje is not favored because it is perceived as an ideological imposition that has little reality for Indigenous peoples. Additionally, the informants do not have enough clarity on whether the national integration based on the mestizaje is useful for them, since it implies the abandonment of the Indigenous languages and cultures. The most revealing aspect of this information is that mestizaje, alluding to a common origin, neutralizes the ethnic origins of each ethnic group. Therefore, Indigenous people reject mestizaje because it is equivalent to assimilation and they do not long to be mestizos.

While we have taken a look at the voices of intellectuals from years ago on what they think of the mestizo, it is also valid to know what the mestizos think of the indigenous people, research that includes more recent data. In other words, if we were to reverse the question and say: how do the mestizos see the Indians?

7. The Results of the Survey Ser Indigena (Being Indigenous)

The National Survey of Indigenous People 2015 (

Gutiérrez Chong 2015) provides a unique national picture, for it reports on the perceptions of mestizos towards Indigenous people.

This survey is one of 25 surveys, from the collection Los mexicanos vistos por si mismos (Mexicans seen by themselves), which was carried out by the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 2015. The Ser Indígena Survey was applied to 1500 households nationwide. The mestizo respondents were mostly men (51.9 percent) while women made up 48.1 percent. On average, they were 38 years old and 95.7 percent could read and write.

This section uses only two questions from the survey to get a general look at what mestizos perceive in relation to more than 10 million speakers of indigenous languages across the country. Could you mention the names of three Indigenous groups? And, do you consider that you have Indigenous roots?

Could you mention the names of three Indigenous groups that you remember? The question, although very simple, reveals that the mestizos have an evident lack of knowledge of the Indigenous people. Three out of ten mestizos answered that they did not recall the presence of any Indigenous group, while one out of ten did not answer the question. Most of the interviewees responded that they are aware of the existence of Indigenous groups in southern Mexico.

Do you consider that you have Indigenous roots? Six out of ten people recognized that they do have ethnic roots at least to some extent. These roots are placed in relation to the consumption of food, traditions, and customs.

To complement the above, the interviewees clearly perceived that the fact of being Indigenous is a disadvantage. This is because four out of ten people said that being Indigenous causes discrimination and racism, two out of ten believed it causes marginalization and poverty, while one in ten did not have clarity about what it means to be Indigenous.

The perception of the Indigenous people, and the opinion of the mestizos, results in the myth of national integration being active and in transformation. These two scenarios allow me to observe that there is a double perspective: either they contradict or complement each other. For the Indigenous people, it arouses rejection, because their origins predate the arrival of the Spaniards to the American continent, while for the mestizos, it is perceived that they know little or nothing about their Indigenous side. Thus, the myth has been useful to build a narrative to exalt the mestizo to be the repository of national identity or Mexicanity. The tensions between mestizos and Indigenous people are not resolved. The results reveal the gap that continues to exist between Indigenous and mestizos in today’s society. Notwithstanding the state’s integrationist strategy to forge the nation based on the common genealogy of mestizaje, the mixture of culture and race is more than 500 years old.

8. Conclusions

In Mexican nation-building, the myth of mestizaje as a national integration strategy offers ample evidence. The myth reveals its powerful ethnocentrism, while merging into a simple narrative that illustrates the descendants of the founding couple. In this sense, mestizaje is the genealogy of the ethnic ancestors of the Mexican nation. The mestizo bastard of the colonial caste society was turned into the nation’s archetypal hero, hence a set of cultural and educational artefacts to propagate the cosmic race followed. For example, in calendars and textbooks. However, this has been a major problem in terms of how to make the Indigenous people part of the family of the founding couple. Indigenous groups, because of their ethnicity, also have myths of origin, foundation, or descent.

A group of Indigenous people who have received higher education recognize that there is mestizaje, but they do not know clearly if it is a benefit for them. Obviously, they also know the narratives of their origin as a group. Hence, the answer to the main question in this article is that there are numerous genealogies, as there are ethnic groups. The problem is that there is one narrative of origin which is predominant, while many other ethnic narratives remain vulnerable, or are at risk of entering the drawer of oblivion because they lack local institutions, i.e., an ethnic educational system under Indigenous people’s management, for their strengthening or dissemination. The dominant genealogy is maintained by the intervention of the state, which has the monopoly on public education. Despite this symbolic strength and institutional support, the mestizos, who responded to the survey in the last section of this article, did not find anything positive in the Indigenous part that corresponds to them, and they did not know how to value their heritage or ethnic past, but they reiterated that being Indigenous is a disadvantage, since it implies poverty, discrimination, exclusion, and racism.

Mestizaje speaks of a powerful narrative, but so far it seems to reach a limitation as the nation recognizes other non-Indigenous cultural diversities, such as Afro-Mexicans or the descendants of different Asian migrations, and the latter, although not included in the discussion, will find it difficult to accept mestizaje as long as it is an exclusive Spanish and Indigenous formula.

The perceptions of Indians and mestizos about the myth of national unity, gathered through interviews and a survey, allow us to appreciate that the narrative is dynamic, and may no longer be a common reference, as presumably ethnic groups have ethnocentrism that sustains their own narratives of origin. When intellectuals or spokespersons from different Indigenous peoples raise their own myths of origin, foundation, or descent, mestizaje may begin to collapse, banishing it from the national education system, but there is no indication that this is happening.

For a long time, academic and political circles stopped addressing the issue of racism because it was believed that mestizaje had tempered it. However, since the last decades of the last century, with the public presence of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, EZLN, one of whose main goals was to denounce the poverty of the Indigenous populations, the issue has re-emerged. There is an updated discussion on racism around skin color associated with poverty and lack of opportunities; as a novelty, ethnic young people highly recognized in national and international public scenarios are participating in this discussion, for example, the actress Yalitza Aparicio, the actor Tenoch Huerta, the linguist Yásnaya Aguilar, and the soprano María Reyna, among others. Without a doubt, the research agenda to study racism and anti-racism will have to include how the narrative of mestizaje within the new generations of Indigenous people is being perceived.

The responses of my interviewees expressed rejection of the myth of national unity and expressed that they do not want to be mestizos. Therefore, it is necessary to go deeper with more empirical data to see if Indigenous people feel discriminated against by mestizos, since there is a great diversity of mestizos, for example, there are poor mestizos with dark skin color and Indigenous appearance, and white mestizos with a European appearance, and so on.

Considering the multiculturalism and interculturality policies that are changing the ideological and structural direction of the nation state, the figure of the mestizo is insufficient. In the twenty-first century, the emancipatory airs of constitutional multiculturalism expressed in the reform of article two has meant the right to free determination and the autonomy of Indigenous peoples, so other ways could be built to activate more origin narratives that strengthen the diversity of peoples in the Mexican territory. It is possible that, in a plurinational or multi-ethnic state, there is room for many origin narratives or genealogies.