Abstract

Genealogy is important to Aboriginal societies in Australia because it lets us know who has a right to speak for country. Our genealogy binds us to our traditional country as sovereign nations—clans with distinct languages, ceremony, laws, rights and responsibilities. Since the Native Title Act 1993 was passed by the Keating government, hundreds of Native Title claims have been lodged. The first Native Title claim to be lodged on Badtjala/Butchulla country was in 1996 by my great aunty, Olga Miller, followed by the Butchulla People #2 and the Butchulla People (Land & Sea Claim #2). Consent determination was awarded for K’gari (Fraser Island) in 2014 and for the mainland claim in 2019. As a sovereign nation, we have undergone many decades of deprivational longing—physically separated from our island, but in plain view. This article is written from a Badtjala lens, mapping generations of my Wondunna clan family through the eyes of an artist-academic who has created work since 1986 invested in cultural responsibility. With the accompanying film, Out of the Sea Like Cloud, I recenter the Badtjala history from a personal and local perspective, that incorporates national and international histories.

1. Introduction: The Badtjala Nation

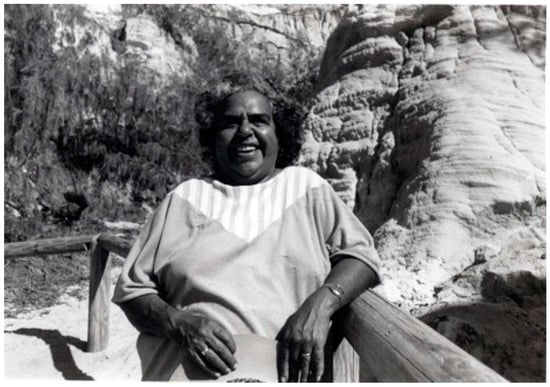

I am from the Wondunna Clan of the Badtjala nation. Our traditional country is the region encompassing all of K’gari/Fraser Island off of the southern coast of Queensland, Australia. K’gari, the largest sand island in the world, is under the management of Queensland National Parks and Wildlife Service. She (the island) is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. On the mainland, our traditional boundaries extend from Double Island Point in the south, to Bauple Mountain in the west, and to the mouth of the Burrum River in the north (Reeves and Miller 1964). We speak as a sovereign nation as our rights have not been ceded. Our ongoing commitment to our country, and the reintroduction of our language back into common usage, have been long and active processes full of tenacity. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Fiona Foley’s mother, cultural activist Shirley Foley, on K’gari (Fraser Island). Photograph courtesy of Fiona Foley.

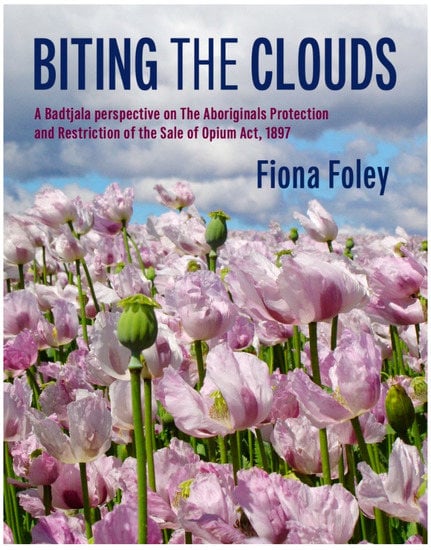

Like my known and unknown ancestors, my life has been about the fight for justice for Aboriginal people. My platform has been through the visual arts, which has included solo exhibitions, public art commissions, public speeches, a Ph.D., and a publication entitled Biting the Clouds (Foley 2020). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The cover of Fiona Foley’s forthcoming book, Biting the Clouds, which refers to a Chinese expression for smoking opium. The photograph by Foley is a field of poppies.

Throughout my career, I have joined other Aboriginal artists, public intellectuals, academics and writers who have been at the forefront in changing the dominant colonial narratives and confronting structural racism. As Bruce Pascoe states, “Any nation’s artists and thinkers set the tone and breadth of national conversation” (Pascoe 2019, p. 100). Decolonizing the histories of Queensland has been a lifetime passion of mine. In this article, I demonstrate that while English colonists and the Western academy wrote a history for our people, the gaze has always gone both ways. See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Fiona Foley’s Watching and Waiting from her series Horror Has A Face, #8. (2017) Fujiflex Digital Print. Edition 15. 45 × 80 cm. Reproduced courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

In the historiography of place, there have been a number of events beyond our control that have shaped who the Badtjala are as a people. In a European linear narrative, one of those key dates was 1836 (Schaffer 1995; McNiven et al. 1998). The Badtjala name for our island, K’gari, became known as “Fraser Island” after the Stirling Castle shipwrecked off the coast of the island. Captain Fraser was speared and his wife, Eliza—according to legend—was rescued two months later by an escaped convict who had lived with tribal Aboriginals in South East Queensland and could speak several of their languages (Miller 1998; Foley 1998).

In Larissa Behrendt’s Finding Eliza (Behrendt 2016) she unpacks British fears of cohabitation by highlighting, “once these anxieties found expression and form in narratives such as Eliza’s, they justified the mechanisms for surveillance of Aboriginal people through policing practices, legal control and government policy.” The unspoken fear, in Eliza’s case, was that this white woman could be sexually violated by Aboriginal men if not rescued. Racialized anxieties have formulated many patterns of structural behaviours used to subjugate Aboriginal men, women and children in Australia.

The intensity of the unknown for the Badtjala people and the English, I imagine, would have created a heightened sense of curiosity upon seeing one another. The Frasers were not our first brush with the English on K’gari. In May of 1770, many Aboriginal sovereign nations watched a foreign vessel, the Endeavour, sail up the eastern coast for days, passing nation after nation, who communicated with one another about its progress. The Badtjala people were unique because, not many people in the world would be aware, they created a song recounting what happened when the ship passed by our country on May 20th of that year. The song takes place on a volcanic headland of K’gari known in Badtjala as Takky Wooroo. What I love about this song are the layers of metaphors contained within one verse:

One of those strangers was Captain James Cook, who named three sites on Badtjala country, including Takky Wooroo, which he called “Indian Head”. This renaming provides the first evidence of British racialization in Australia—an attempt to categorize and rank people, as Jodi A. Byrd writes in The Transit of Empire, in order “to facilitate, justify, and rationalize the state-sponsored violence that tear land, resources, and sovereignty from indigenous people”(Byrd 2011, p. 54). Cook chose the name not because the landscape looked like an Indian’s head, but because the English mariners felt the need to classify and racialize thousands of Badtjala people amassed on top of the rock observing them.The ship rose up out of the sea like cloud,and kept near land for three or four days.One day it came in very close to Takky WoorooAnd they saw many men walking around on it.They asked each other who are these strangers?And where are they going?

At the sight of Aboriginal people, Cook and Sir Joseph Banks engaged in a discussion about their skin colour and hair texture to try and define a new “race” of humans. For instance, in Cook: The Extraordinary Voyages of Captain James Cook, Nicolas Thomas writes that the English were perplexed because, Aboriginal hair, “was not woolly or frizzled but as Cook put it ‘black and lank and much like ours’” (Thomas 2003, p. 114). Not wanting to classify them as Negroes, they referred to them as Indian. Unfortunately, Thomas does not write about the Badtjala’s perspective on Cook in his publication. Like the international tourists who visit K’gari on a daily basis, he is unaware of their existence, let alone their song. This one-sided colonial narrative silences Badtjala voices and has far-reaching collateral damage in society ranging from the academy to Australian tourism.

2. Decolonizing the Colonial Narrative Through Art

As a five-year child, I remember looking across to K’gari and experiencing a deep sense of loss. It was a loss for my country, for my culture, and for my old people, who were forced off the island. A deep visceral connection to my country was already in my soul. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Fiona Foley’s Silent Witnesses from her series Horror Has A Face, #18. (2017) Fujiflex Digital Print. Edition 15. 45 × 80 cm. Image reproduced courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

Soon afterwards, I became a racialized person—not from my family, but by others—when I entered the school gates at Urangan, Hervey Bay. In the 1970s, my parents faced much discrimination and, at one point, were forced to move to Mt. Isa to escape the pressures of race hatred because of their mixed marriage. By then, I was in third grade. At the time, I did not know I was destined to be an artist, but my art practice has sustained me for the past 35 years. In 1986, while studying in the sculpture department at Sydney College of the Arts, I created a sculpture based on a story my mother, Shirley Foley, told me about a massacre on my country along the Susan River. Many oral histories of genocide are carried, in living memory, by Aboriginal people. That image stayed with me of Badtjala people being maimed, killed, or fleeing on foot. It was a powerful history to carry and to make of it—something. The sculpture I created back as a 22-year-old art student was titled Annihilation of the Blacks and was bought by the National Museum of Australia—one of the museum’s “first major acquisitions of a city-based Aboriginal artist” (Quail 2000). See Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Fiona Foley’s Annihilation of the Blacks (1986). Permanent collection of the National Museum of Australia, Canberra. Image reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Aboriginal art and politics have had an uneasy relationship in this country. Years after the initial purchase, Annihilation of the Blacks courted controversy from the John Howard government in the early 2000s and played a role in the History Wars unfolding nationally (Smith 2001, p. 657). In 2003, the National Museum of Australia produced “Contested Frontiers,” an exhibition with a companion book that reconsidered the primacy of frontier violence and the impact of generations of forced separations, known as the “stolen generations,” of Aboriginal children from their parents (Attwood and Foster 2003). After conservative commentators protested the exhibition, the museum board did not renew director, Dawn Casey’s contract, which signaled, to both artists and curators, a wave of censorship in public institutions (Casey 2003).

“Contested Frontiers” challenged a statement that I have often heard from white Australians: “Australia was settled peacefully”. In fact, we were not passive in the takeover of our country. Every inch of Queensland soil has been fought over and bloodied. This history of Queensland is not taught in schools or universities. It is a history I have pieced together through reading books since the age of 24. I wanted to learn more about the attitudes held by colonial men and women, and the Aboriginal people who repeatedly attacked their invaders with strategic guerrilla wars. In 2008, I created Dispersed with 303” calibre blank bullets after reading historians such as Henry Reynolds, Rosalind Kidd, Tony Roberts, Raymond Evans, and Jonathan Richards, (Reynolds 1981; Kidd 1997; Evans 1999; Evans et al. 1975; Roberts 2005; Richards 2008). See Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Fiona Foley’s Dispersed (2008). Charred laminated wood, polished aluminum, 303” calibre bullets (blank). Each letter 51 cm high × 25 cm wide. Entire sculpture is 500 cm wide. Permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Image courtesy of the artist.

Australia carries deep wounds from the trauma of the wars fought against our people. After massacres, Aboriginal people were not allowed to bury our dead (Rowley 1970). We carry it inside our souls whether we are conscious of them or not. The brutality, in turn, has also affected the perpetrators and their descendants. Many Aboriginal people carry deep psychological scars from what Judy Atkinson terms “intergenerational trauma” (Atkinson 2002). As Alexis Wright argues in Meanjin, “the physical control and psychological invasion of Aboriginal people has continued as it began, from the racist stories told about Aboriginal people from the beginning of colonization two centuries ago” (Wright 2016). Racism continues to be a societal burden I’ve learned to carry—that gaze wrapped up in judgment from a white society and white individuals. For me, it manifests itself in everyday educational environments, including in my present-day status as an academic.

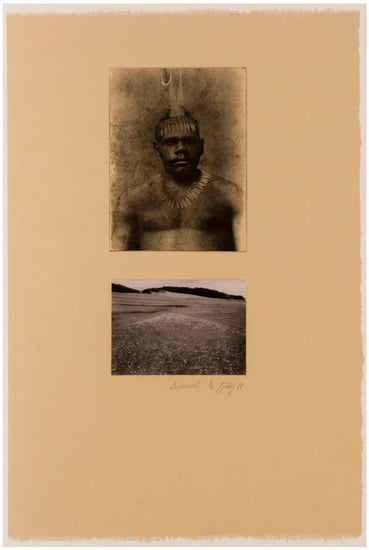

3. Visiting Boni

In 2011, I was contacted by Daniel Browning, the host of the AWAYE!—a program on ABC Radio National dedicated to Aboriginal arts and culture—to go to Lyon, France with him to view a life size plaster cast of a Fraser Island man whose name was Boni (also known as Bonangera or Benanyora). Historical research on Boni and his two other companions, Durono (also referred to as Jurano, Turano or Alfred) and Borondera (Dorondera or Suzanne), would form the basis of a radio program entitled Cast Among Strangers. This was a very unusual request. I said yes due to the fact that images of Boni that Daniel sent to me looked very much like my great-great-grandfather, Willy Wondunna, also known as Caboonya. The familial resemblance was astounding. In a black and white image, I had come to know of Caboonya as a young man he is wearing a head-dress of two seagull feathers, a band around his forehead of kangaroo teeth and a necklace of kangaroo teeth. See Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Fiona Foley’s artwork from her 1988 series Survival includes a photograph of her great-great grandfather, Willy Wondunna, also known as Caboonya, and a shell midden on K’gari. Image courtesy of Fiona Foley.

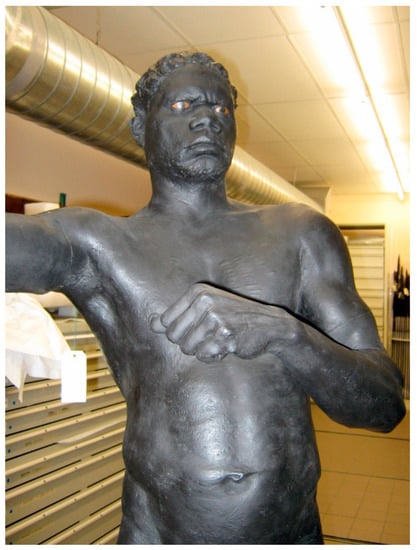

In this image, Caboonya’s facial features also resemble my brother’s, Shawn Foley. Over three generations, there is a genealogical trace of blood ties. The question was how did Boni’s full body cast in plaster come to be in the collection of the Musée des Confluences? See Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Full body cast of Boni at the Musée des Confluences in Lyon, France. Photograph courtesy of Fiona Foley.

It is an intriguing story with many questions and few answers. In 1883, Boni, Durono, and Borondera were at the Dresden Zoo in Germany as part of human circuses traveling for European audiences who paid to see the “Missing Link,” “Cannibal King,” and other tropes of Western scientific racism (Rothfels 2002; Poignant 2004; Foley 2011). They performed acts like throwing boomerangs or climbing large poles with bare feet and hands. In London, I met with Roslyn Poignant, who has written extensively on Palm Island Aboriginals sent from Australia to America and Europe and asked her what happened to Durono and Borondera. Their last place of archival recording was in Dresden. Roslyn suggested that most likely influenza was the source of their deaths. Boni travelled on with others to France in those touring carnivalesque shows. Cast in a position ready to throw a boomerang, he carried tribal cicatrices both on his front and high on his buttocks and hips. I viewed Boni with all sorts of emotions. However, what I will take away with me is that he looked strong, handsome and intelligent.

It is difficult to know where Boni fits into the larger Badtjala story apart from his existence in Lyon. He was of a different generation than Caboonya, but their time periods overlap. My great great-grandfather, Willy Wondunna, was initiated in 1865. He married an Aboriginal woman whose name is Eulie (Marion) and they had one son, Frederick Wondunna. In 1942, he obtained a Certificate of Exemption from the Aborigines Welfare Board, which allowed him to live outside of the laws of The Act and regulations until he passed away at 98 years old. His influence continued after his death as he was key in our two Native Title claims with the Federal Court of Australia in 2014 and 2019 as our apical ancestor whom we are all descended. My extended family and I just called him Great.

During Great’s life he observed “rapid cultural change” in the Wide Bay region—some of it unfathomable to him (Loos 2017, pp. 160–61). One of those changes was an attitudinal shift in white settlers toward Aboriginal people, which was tied to economic rationalization to “let the blacks in” instead of hunting them from townships, cattle stations, and districts as had been their practice during the decades of open frontier warfare (2017, p. 161). Also, taking place at this time were inducements to trap Aboriginal workers into a life of degradation and servitude. Following the end of brutal frontier violence, the use of “opium ash” or “opium dross” as payment for Aboriginal workers created a profound cultural schism. The complete halt of ceremonial practices was one of the outcomes.

4. Opium

There is a long history of opium use in Queensland, and up until 1897, it was legal because the economics were lucrative. In addition to the money made for its importers, the issuing of government licences, white license holders, Chinese license holders, and established opium dens in the region, Queensland colonialists introduced to Aboriginal groups to addict them as a free labour force. See Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Fiona Foley’s Opiate of Opulence from her series Horror Has A Face, #9 (2017) Fujiflex Digital Print Edition 15. 45 × 80 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

Only when The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act was introduced did a regime of control, segregation, removals and harsh penalties come into force for all Aboriginal populations across Queensland (Foley 2020). To stamp out opium use by Aboriginals, the first experiment under Archibald Meston, the Southern Protector of Aboriginals, was established—an Aboriginal Mission on the western side of K’gari at White Cliffs that was later relocated to Bogimbah Creek (Foley 2020). See Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Fiona Foley’s Missionary Zeal from her series Horror Has a Face, #17 (2017) Fujiflex Digital Print. Edition 15. 45 × 80 cm. In this photograph, Foley recreates a funeral at the Bogimbah Mission on K’gari, which was run by Reverend Ernest Gribble from 1900-1904. The Mission was closed and Badtjala people were forced to leave the island. The location of the site was lost to memory, but in 2014, with the help of Badtjala rangers on K’gari, the original settlement was located, along with 70 Aboriginal graves (Atkinson 2014). Image courtesy the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

When I first heard of this act, I was initially intrigued by the two words “Aboriginals” and “opium” in the same title. Only through reading did I find out how draconian the laws were. The Act contained 33 clauses governing Aboriginal lives with its tentacles reaching into my traditional country and the lives of 51 Badtjala people living in Maryborough who were forcibly removed to the mission on K’gari under Archibald Meston’s direction. My great-grandfather Fred Wondunna, and grandfather Horace Wondunna, did not come under The Act due to Clause Ten:

10. Every aboriginal who is—

- (a)

- Lawfully employed by any person under the provisions of this Act or the Regulations, or under any other law in force in Queensland;

- (b)

- The holder of a permit to be absent from a reserve; or

- (c)

- A female lawfully married to, and residing with, a husband who is not himself an aboriginal;

- (d)

- Or for whom in the opinion of the Minister satisfactory provision is otherwise made;

shall be excepted from the provisions of the last preceding section.

My paternal family’s employment in the fishing and timber industry on K’gari saved them from mission life.

5. The Wondunna Clan

At the beginning of the 20th century, my great-grandfather, Fred Wondunna, mostly lived on K’gari as a timber getter. On the island, he met Ethel Marion Reeves, the sister of the Rev. Ernest Gribble, who ran the Bogimbah Creek Mission. Fred was a rule breaker. Marriage to a white woman was not permitted in Queensland under The Act, so they crossed state lines. Already widowed, with one child from her former marriage, Ethel wed Fred in Sydney on 30 December 1907. They came back to live on the island at Wondunna’s Camp—away from prying eyes for her and steady employment for him. They had five children: Horace, Constance, Wilfred, Nowell and Olga.

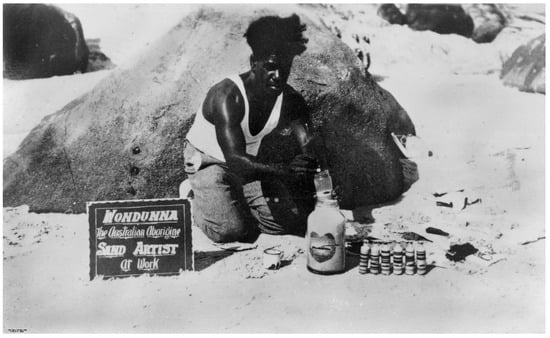

At some point, Fred left the marriage to live independently away from the family. I believe it was due to having a broken heart. For over 14 years, he lived in Lismore, New South Wales where he dived and worked deep sea oyster beds. In a black and white photograph, there is a striking image of his masculinity on Kirra Beach. He is filling bottles of coloured sand with designs of ships on the inside of the glass. The sign reads, “Wondunna, The Australian Aborigine, Sand Artist at Work.” See Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Fred Wondunna at Kirra Beach on the Gold Coast of southern Queensland. Photograph courtesy of Fiona Foley.

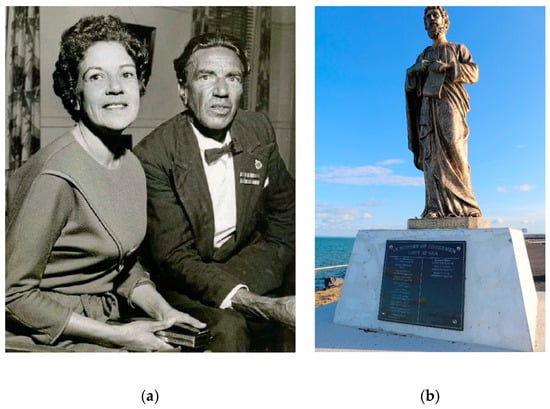

Fred returned to Maryborough towards the end of his life and passed away aged 70 on the 21 February 1956. Two of his children—my great uncle Wilfie and great aunty Olga—worked together writing and illustrating a children’s book, The Legends of Moonie Jarl (Reeves and Miller 1964). I grew up pouring over the illustrations of my family’s book. I never saw anything like it in other places. It was a treasured cultural object in our house that is now acknowledged as, “the very first Indigenous children’s book authored by Aboriginal people” (Miller 2016). See Figure 12a. It was also the start of the Wondunna clan’s contribution to Badtjala cultural life through publications. In 2014, The Legends of Moonie Jarl was re-published for its 50th anniversary by the Indigenous Literacy Foundation. My cousin Glen Miller (Aunty Olga’s son) gave a speech at the University of Southern Queensland, Hervey Bay and many in the local community gathered for this joyous event (2016).

Figure 12.

(a) Olga Miller and Wilf Reeves. Photograph courtesy of Fiona Foley; (b) The memorial, In Memory of Fishermen Lost at Sea, Urangan, which commemorates lives lost at sea in Hervey Bay, includes the name of Fiona’s grandfather, Horace Wondunna. Photograph courtesy of Fiona Foley.

Uncle Wilfie and Aunty Olga’s achievements were outstanding milestones for their time. Their brother Horace was also a high achiever in commerce. I never met my grandfather, Horace Wondunna, because he died at sea under mysterious circumstances, along with two other crew members (Charlie Warner and Sam Kanupan), at the young age of 31. His body was never found. That fateful fishing trip would have been the last payment on his commercial fishing boat. Horace Wondunna and Sammy Kanupan are remembered on the plaque along with others, In Memory of Fishermen Lost at Sea, Urangan. See Figure 12b.

This tragedy set in train a momentous change for the lives of his wife Alma, and their four children: Noela, Coygne, Horace, and my mother, Shirley. My mother, the youngest of the four, grew up never knowing her father. Yet she, too, would inherit a decisive strength of character and an independent way of viewing the world.

6. Legacies

In 1986, a headline read, “Fraser Island Lease Sought” accompanied by an image of my mother, Shirley Foley, teaching Aboriginal culture at Hervey Bay College (Hervey Bay-Fraser Island Sun 1986, p. 5). A community leader, she understood how to involve political figures and key advocates to support visionary, large-scale projects. At this early stage, the project’s working title was “Hervey Bay Aboriginal Education and Culture Centre,” and would later be recognized as Thoorgine Education and Culture Centre.

Mum’s dream, and one that my family also lived and breathed alongside her, was to get land back on K’gari. The Chronicle article stated an Aboriginal group had applied for a six-hectare parcel of land on the island. The local mayor, Ald. Judy Rice, politician Bob Katter, and Queensland University anthropologist Dr. Peter Laurer fully supported the venture. On 1 January 1990, 6.5 hectares of land adjacent to the Worali Track were dedicated to the Badtjala people as part of a 20-year, Queensland Special Lease. Mum was a visionary and ahead of her time, but if important legacies are not talked about and celebrated, they can quickly be overlooked.

Mum’s passions in life were many—from the retrieval of Badtjala language to cultural exchanges with other Aboriginal people from Maningrida (Arnhem Land), the Mutujulu community (Uluru) and Palawa women weavers (Tasmania). Over the years, she also hosted large workshops at Thoorgine and other places on the island with the assistance of Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service whom she had built a great relationship with.

Mum passed away in 2000 aged 62 while she was still active in the community. She was an adopted elder at Urangan Point Primary School and set up two scholarships with the local university: the “Horace Wondunna Scholarship” (named after her father) and the “Wondunna Scholarship” (named after our clan). Looking back over the past 20 years, it now seems to me how communities can easily lose sight of contributions of previous generations if their work isn’t celebrated and brought into discussions of contemporary activism.

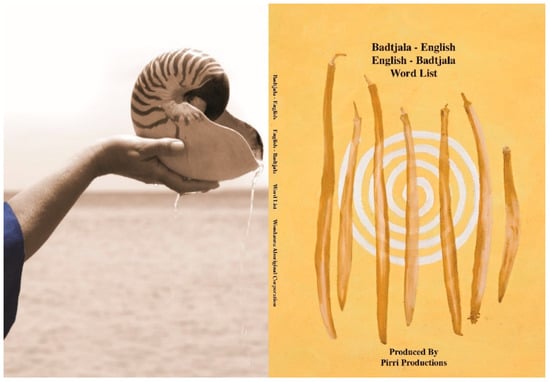

In preparation for the International Year of Indigenous Languages in 2019, I returned to Mum’s work in the area of Badtjala language retrieval and maintenance. Over many years, one of her outstanding legacies was the out of print, Badtjala─English English─Badtjala Word List. A comprehensive gathering of Badtjala words structured into subheadings and categories, it was first published in 1996. This level of scholarship would be worthy of a PhD in the academy, but Mum only attained a grade 6 education due to being raised by a single parent in poverty. The Wondunna Aboriginal Corporation and Pirri Productions republished Mum’s Badtjala Dictionary in 2018, and again in 2019.

Her dictionary is extremely important because we do not speak our language fluently anymore. By the time I was born all my old people only spoke Badtjala words. Piecing the word list together was a twenty-year labour of love for my mother. She researched archives in libraries and museums to find colonial journals and notations such as Curr, Meston, Howitt, Armitage, Winterbottom and Watson. Mum also became involved with the Aboriginal language movement in Queensland. She ran Zone 2 of the Language Program in Central Queensland, travelling vast distances to fund local organizations and individuals working on their own language maintenance and survival, and also attending conferences in Brisbane. When she was not travelling, Mum would make her own flash cards and go into primary schools in Hervey Bay to teach children Badtjala words. In her eulogy, written by my brother Rowan Foley, he reflects, “Shirley spent her life working as a tireless community worker devoted to her family, culture and traditional country” (Foley 2000). See Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The fourth edition of Badtjala─English/English─Badtjala Word List, produced by Pirri Productions. First published 1996, Fiona Foley designed the artwork on this 2019 edition. Front Cover: Fiona Foley’s Mangrove Pod (2000). Oil on linen. Back cover: Fiona Foley’s The Oyster Fisherman #1, (2011) Ultrachrome print on paper. Images courtesy of the artist.

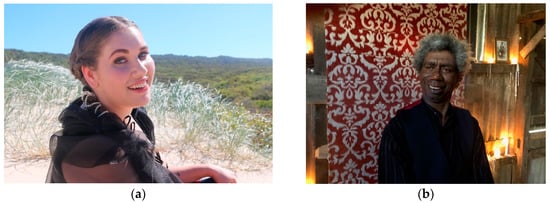

In 2019, The International Year of Indigenous Languages I had the opportunity to bring my mother’s work back to life again through the re-publication of her dictionary and a new film. I secured a grant from the Australian Government—Indigenous Languages and Arts Program which allowed me to create big. I directed a short film titled Out of the Sea Like Cloud. The film was set over two locations on K’gari at Takky Wooroo and a historical derelict building on Wharf Street, Maryborough where I created, with set designer Scott Harrower, a luxurious and textured opium den. This location was historically accurate when Maryborough was a thriving port city for the import of opium situated on the Mary River. Two historical timelines are presented in the film from 1770 and 1897. The song features the English translation and re-presents new verses in our Badtjala language for the first time regarding the Endeavour encounter. We were able to access the Endeavour replica owned by the Maritime Museum in Sydney for authenticity. The production was an epic feat filming at Indian Head racing against king tides and a full moon.

I commissioned Teila Watson, also known as Ancestress, to write and record a new song using the Badtjala Dictionary. I first saw her perform one night in 2013 in front of my sculpture, Witnessing to Silence, on Roma Street with the Brisbane Magistrates Court as the backdrop. She was singing her own song titled, One by One. The sculpture identifies 94 massacre sites on the public record in Queensland. Teila’s lyrics were equally as powerful and haunting. I made a promise to myself that I would one day like to work with her. That memory stayed with me for years. In 2019, I asked Teila to use the work my mother had put together to create a song for the film.

Our collaboration was no easy feat. Teila had to teach herself our language from the pages of the Badtjala Dictionary. We were living in two different locations in Queensland—I was on country in Hervey Bay and Teila was in Brisbane. I posted Teila one of the newly printed dictionaries and asked her to start the song construction from scratch. I left all of those choices up to her. When I travelled to Brisbane and Teila first sang the song to me, I had tears rolling down my cheeks. Our language had been sleeping for many years and was awoken. It was the first time the full weight of my mother’s work had been activated in such a space. I got to witness all of her hard work through Teila’s solo rendition. In Out of the Sea Like Cloud, Teila plays the character named Spirit Woman. The other lead actor is Joe Gala, who keeps the film moving along through his various antics and realizations. I call the film genre I embarked upon magical realism. The cast comprised of eleven non-actors from the region. See Figure 14a,b.

Figure 14.

(a) Teila Watson, also known as Ancestress, on location on K’gari for Out of the Sea Like Cloud. Photograph by Fiona Foley; (b) Joe Gala, one of the lead actors in the film, who plays a Badtjala man who holds onto their song about The Endeavour passing by K’gari in 1770. Here he is shot on location at an opium den created by Scott Harrower and Fiona Foley. Photograph by Fiona Foley.

On 14 December 2019, we premiered Out of the Sea Like Cloud at the Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. For decades, I watched my mother fight for land, recognition of Badtjala people in the broader Australian society, and the right to economic independence from the state government. I learnt many things from her and had a close relationship with her. Shirley Foley was a powerhouse of determination in promoting Badtjala culture wherever she went. Last year, Mum’s research underpinned my research. Our lives came together through making Out of the Sea Like Cloud. She continues to live on in my work—that’s what strong cultural leaders do. Over the years I’ve often been told I am courageous. However, I see it more in terms of having a deep sense of justice. Growing up not knowing the historical truths of Australia’s beginnings led to an internal call to want to know more.

Funding

This article received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Atkinson, Judy. 2002. Trauma Trails: Recreating Song Lines: The Transgenerational Effects of Trauma in Indigenous Australia. North Melbourne: Spinifex. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Bruce. 2014. Queensland Scientists Discover 70 Aboriginal Graves on Fraser Island Lost for More Than 110 Years. ABC News. November 9. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-11-09/scientists-discover-70-aboriginal-graves-on-fraser-island/5877802 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Attwood, Bain, and Stephen Foster, eds. 2003. Frontier Conflict: The Australian Experience. Canberra: National Museum of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Larissa. 2016. Finding Eliza: Power and Colonial Storytelling. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, Jodi A. 2011. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis and First Peoples. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Raymond. 1999. Fighting Words Writing about Race. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Raymond, Kay Saunders, and Kathryn Cronin. 1975. Exclusion, Exploitation and Extermination: Race Relations in Colonial Queensland. Brookvale: Sydney, Australia and New Zealand Book Company Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Dawn. 2003. Culture Wars: Museums, Politics, and Controversy. Open Museum Journal 6: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Fiona. 1998. Blast from the Past. In Constructions of Colonialism: Perspectives on Eliza Fraser’s Shipwreck. Edited by Ian McNiven, Lynette Russell and Kay Schaffer. London: Leicester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Fiona. 2011. When the Circus Came to Town. Art Monthly Australia. November Issue 245. Available online: http://www.artmonthly.org.au/issue-245-november-2011 (accessed on 4 July 2020).

- Foley, Fiona. 2020. Biting the Clouds. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Rowan. 2000. Eulogy Shirley June Foley (7 December 1937–23 July 2000), Unpublished Family Document.

- Hervey Bay-Fraser Island Sun. 1986. Fraser Island Lease Sought. Hervey Bay: Hervey Bay-Fraser Island Sun, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, Rosalind. 1997. The Way We Civilise: Aboriginal Affairs—the Untold Story. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loos, Noel. 2017. Invasion and Resistance: Aboriginal-European Resistance on the North Queensland Frontier 1861–1897. Salisbury: Boolarang Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNiven, Ian, Lynette Russell, and Kay Schaffer, eds. 1998. Constructions of Colonialism: Perspectives on Eliza Fraser’s Ship Wreck. London: Leicester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Olga. 1998. K’gari, Mrs. Fraser, and Butchulla Oral Tradition. In Constructions of Colonialism: Perspectives on Eliza Fraser’s Shipwreck. Edited by Ian McNiven, Lynette Russell and Kay Schaffer. London: Leicester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Glen. 2016. Legends of Moonie Jarl…The First Aboriginal children’s book by Aboriginal people. Indigenous Literacy Foundation. June 6. Available online: https://www.indigenousliteracyfoundation.org.au/news-events/legends-of-moonie-jarlthe-first-aboriginal-childrens-book-by-aboriginal-people (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Pascoe, Bruce. 2019. Salt. Carlton: Black, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Poignant, Roslyn. 2004. Professional Savages: Captive Lives and Western Spectacle. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quail, Avril. 2000. Laced Flour and Tin Boxes: The art of Fiona Foley. In World of Dreamings: Traditional and Modern Art in Australia. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, Available online: https://nga.gov.au/dreaming/index.cfm?Refrnc=Ch8 (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Reeves, Wilf, and Olga Miller. 1964. The Legends of Moonie Jarl. Brisbane: Jacaranda Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Henry. 1981. The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European Invasion of Australia. Victoria: Penguin Books Australia Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Jonathan. 2008. The Secret War: A True History of Queensland’s Native Police. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Tony. 2005. Frontier Justice: 2005. In A History of the Gulf Country to 1900. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothfels, Nigel. 2002. Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, Charles Dunford. 1970. The Destruction of Aboriginal Society. Victoria: Penguin Books Australia Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, Kay. 1995. In the Wake of First Contact: The Eliza Fraser Stories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Terry. 2001. Public Art Between Cultures: The “Aboriginal Memorial,” Aboriginality, and Nationality in Australia. Critical Inquiry 27: 629–61. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Nicolas. 2003. Cook: The Extraordinary Voyages of Captain James Cook. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Alexis. 2016. What Happens When You Tell Somebody Else’s Story? Meanjin. Summer. Available online: https://meanjin.com.au/essays/what-happens-when-you-tell-somebody-elses-story/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).