Abstract

This paper, in the form of walking meditation, sitting, drinking, eating, and traveling among spaces and times, witnesses how the author as a Vietnamese immigrant child living in the United States (U.S.) traces untold stories of their family through family photos. Further, this paper attempts to find, understand and connect the relation between personal and political, between individual and collective, for a Vietnamese re-education camp detainee and his family, situated in political, historical, and cultural context. The use of photo elicitation comes from the desire that the reader can engage with the voices of the family members as they describe events in their past history. In addition, this paper refuses the forms of “category” and “fixed results” in writing up academic research. Rather, it will appear in the form of daily conversation, collected from multiple settings. Simply speaking, this paper is a form of storytelling that invites the readers to oscillate, communicate and think with the author’s family members on this historical journey.

1. Coming In

Our true nature is the nature of no birth and no death. Only when we touch our true nature can we transcend the fear of non-being, the fear of annihilation.(Nhat Hanh 2002, p. 7)

I am standing in front of my grandparents. I am taking a deep breath. I do not go with my parents today to visit ông bà nội (grandparents). I am being here—myself—with them. The path to my grandparents’ home is hilly, glistens and is filled with colorful flowers along the sidewalk. The birds are chirping and flying around this space, and tree branches are opening their arms to white clouds as if they were dancing in a peaceful morning. My parents have settled down in peacefulness, light breeze and green frosted leaves in the U.S. I often come here to look for reflection, enlightenment, and conversation. My grandparents do not talk much, I do most of the talking. They are just being there to listen to me. They are some of the most patient people I have ever known. I am wondering how they practiced that patience; perhaps, growing up in wartime in Vietnam has provided them with wisdom and strength for younger generations like me.

Today, I am standing in front of my grandparents to urge them to allow me to do a project about our Vietnamese family. After two decades in the U.S., the stories about immigration in our family seem forgotten and untouched. As a Vietnamese child born and raised in Vietnam and recently immigrated to the U.S., I have been curious about challenges and (in)equities that my parents and uncles experienced when they transitioned between two countries. I have been curious about what tactics they used to overcome cultural and linguistic barriers in the period of 1994 to 2004. After 2004, the communication was much better; therefore, our family in Vietnam could easily communicate and was informed about what happened in the U.S. In contrast, before 2004, the communication between the two countries was via photos only. Therefore, having a real conversation with them will help me explore hidden, untold stories about our family during that time.

I bring my palms together, taking the shape of a lotus, placing them in front of my chest, and whispering to my grandparents, “I hope I can have the strength and wisdom to conduct this project. It is a special project for me because this is part of (re)writing our Vietnamese immigrant family story in the U.S. context. Please let me know how I can get it started.” My grandparents are looking at me, silent; however, I do know ông bà nội are thinking along with me throughout this project.

2. Walking

I am walking along the hill. While walking, I am asking myself, “Why do I want to do this project: for the purpose of publication, or for the purpose of “historizing” the past (Scott 1992)?” “What am I doing in this space with my personal story that could be unfitting in a structure of an academic paper?” “How am I going to deconstruct and de-academize (Trinh 2019c; Trinh and Pentón Herrera forthcoming; Trinh and Merino forthcoming) the hierarchical structure of an academic paper while working on this personal project?” “Will my voice continue to be academized to compliance with what it is supposed to be a paper rather than letting the nature of storytelling speak?” “Which path should I be walking next?”

While walking and thinking about how to get this project started, I have learned that there is a growing amount of research on Vietnamese studies recently. For example, there are essays that discuss connections and disconnections in Vietnamese ethnographic research (Taylor 2016), stories about Vietnamese second generations in the U.S. (Espiritu and Tran 2002) and in Europe (Bloch and Hirsch 2018), and negotiations about cultural adaptation in Vietnamese transnational adult immigrants in the U.S. (Nguyen 2019). As a Vietnamese immigrant, the first-generation child in the family to pursue a doctorate focusing on language and literacy, I am humbled and proud to see how my homeland, my country, my peoples, my cultures, are presented and brought into academic papers. However, the voices of some of these studies are structurally following a rigidly academic paper; I refuse to follow that rigidity in this space. I want to share Vietnamese stories in a Vietnamese way what I have inherited and learned from my grandmas and parents when they shared Vietnamese folk stories with me when I was a child. This is who I am as a Vietnamese storyteller, a Vietnamese scholar, a Vietnamese researcher in a country in which I am struggling to find a sense of belonging.

As a result, writing this piece is, indeed, an exploratory and healing process for me and hopefully for the readers who are finding a way to un-/re-learn their roots, identities, histories, and languages. Learning about our Vietnamese immigrant family in the context of critical family history, identity, and historical memories (Sleeter 2008) is laying the very first bricks in building a bridge of understanding and (re)connecting with a larger picture of my ancestors and their untold stories. This piece is thus going to explore my journey as a Vietnamese immigrant child living in the U.S. and to trace untold stories of my family. Further, beyond the scope of family histories, I want to explore the connection between personal and political, between individual and collective, for my grandpa (as a political prisoner) and his family, in relation to new Vietnamese immigrants in the U.S. context. As Taylor (2016) states, “As the nation has changed, connections have remained central to what it means to be Vietnamese” (p. 1). This project is thus my process of how to re-learn (1) what it means to be Vietnamese in the U.S. context, (2) how Vietnamese-ness looks in Vietnamese family history, and (3) how my understanding of my ancestors and Vietnamese family shape my teaching and research. As a result, I hope readers, specifically Vietnamese-American immigrants and young generations, will partially (Haraway 1988) be able to learn Vietnamese family history and find their own ways of tracing their family history after leaving this space.

2.1. “Methods”

I am walking and looking at tree branches along the sidewalk. They are extending their arms to me as if they are trying to tell me something. While resting my eyes on these branches, I am thinking, “How can I create a connection between my family stories and the reader, like tree branches are extending their arms to reach me?”, “How can I connect the dots of different past and current events of my family to paint a bigger picture situated in cultural and historical context?”. My mind is becoming chaotic while I am trying to walk meditatively.

I am breathing in and out, slowly…

As Thầy Thích Nhat Hanh (2015), a Vietnamese Zen master, philosopher, and thinker, advises me on walking meditation:

Coming back to the island of myself. When life seems like a turbulent ocean, we have to remember we have an island peace of inside. Life has ups and downs, coming and going, gain and loss. Dwelling in the island of self, you are safe.(p. 87)

To my understanding, according to Thầy, I will need to come back to myself to figure out where I should I start this project, where I can create connections and connect the dots. Due to a family situation in which my grandpa and his family immigrated to the U.S. in 1994, which is almost 26 years ago, I do not have many historical documents with me, except the pictures we brought from Vietnam. These pictures, which were sent by our uncles and grandparents from the U.S., were the only memories that we have been carrying from Vietnam to here. “Why don’t I start with a photo?” I think. Specifically, I think about how the power of a picture could think with me and guide me in “a logical sequence” (Collier and Collier 1986, p. 27) to walk the next step.

Christine Sleeter (2008) describes how she explored her own family “by constructing a family tree that went back as far as possible” (p. 118). In addition, Sleeter used an on-line database and other copies of records such as “marriage records, death certificates, and newspaper articles” (p. 118) to construct a family tree. In our situation, family photos are a helpful tool to help me map out a family tree. Specifically, I decided to use photo elicitation (Collier and Collier 1986; Harper 2002) to initiate an informal conversation with my dad as the first part of this project.

Photo elicitation is “based on the simple idea of inserting a photograph into a research interview” (Harper 2002, p. 13). Collier and Collier (1986) acknowledge the use of photographs in research, “The images invited people to take the lead in inquiry, making full use of their expertise. Normally, interviews can become stilted when probing for explicit information, but the photographs invited open expression while maintaining concrete and explicit reference point” (p. 105). Further, Douglas Harper (2002) asserts, photo elicitation “evokes information, feelings, and memories that are due to the photograph’s particular form of representation” (p. 13). In other words, photo elicitation itself is a method that can invite open conversations that arouse the participant’s emotions and feelings. Further, using emotions and feeling in research, as Ann Cvetkovich (2012) calls “the affective turn,” has “not only made emotion, feeling, and affect (and their differences) the object of scholarly inquiry but has also inspired new ways of doing criticism” (p. 3). Besides, using photo elicitation in this project supports me in finding a communicative and dialogic space with my dad, who will talk about his dad, and in tracing untold stories about family history. As Harper (2002) acknowledges, “Photographs appear to capture the impossible: a person gone; an event past” (p. 23). For me, photographs are not only used to initiate historical conversations in historic contexts, but they are historic contexts. More important, photographs are also a narrator to lead the storyline in this space.

After I identified the “method” in this paper, I needed “theoretical eyes” to see and understand hidden meanings behind historical photos. Therefore, in the next step, I will present a theoretical framework that helps me see and connect stories in this project.

2.2. “Theoretical Framework”

I borrow partial knowledge (Haraway 1988) and nepantla, i.e., in-between-ness, (Anzaldúa 2002) to think with me. Due to intertwining nature of both concepts, each will show me how to “see through” (Keating 2006, p. 9) or “see doubles” (Anzaldúa 2002, p. 549) in the hidden meanings and voices within each picture. In other words, each picture will think with me in this process of discussing historical memories. First, I describe Haraway’s (1988) partial knowledge.

Donna Haraway (1988) argues that knowledge is unfixed and located. She states, “I am arguing for politics and epistemologies of location, positioning, and situating, where partiality and not universality is the condition of being heard to make rational knowledge claims. These are claims on people’s lives” (p. 589). In other words, the knowledge, according to Haraway, is not coming to fullness or wholeness; instead, it is in partiality, is never finished; “it is always constructed and stitched together imperfectly, and therefore able to join with another, to see together without claiming to be another” (p. 586, emphasis in original). From this perspective, I will not look for a “perfect” picture or a “full” story of the pictures I collected; rather, I am only able to connect, understand, and interpret the partiality of the meaning and message of each picture and story. Haraway (1988) adds, “Translation is always interpretive, critical, and partial” (p. 589). Haraway reminds me that there is not a way to interpret something that we “see.” Instead, we ask the question of where, with who, with what limits, and with whose vision we understand the “thing” or “data” we see. Importantly, she emphasizes “double vision” (p. 589) in looking at the subjectivity in the research. Interestingly, discussing the nepantla concept, Anzaldúa (2002) acknowledges that nepantla could lead people to “see double” (p. 549). According to Anzaldúa and Keating (2009), a Chicana feminist, thinker and writer, nepantla:

is the Nahuatl word for an in-between state, that uncertain terrain one crosses when moving from one place to another, when changing from one class, race, or sexual position to another, when travelling from the present identity into a new identity.(p. 180)

Then, in another space, Anzaldúa (2002) describes nepantla as “the site of transformation, the place where different perspectives come into conflict and where you question the basic ideas, tenets, and identities inherited from your family, your education, and your different cultures” (p. 548). She states: “living between two cultures results in ‘seeing’ double, first from perspectives of one culture, then from the perspective of another” (p. 549). In other words, the notion of “seeing double” in nepantla is the result of a continuous negotiation of different identities, perspectives and positionalities that come into one place. The people in nepantla state, or Nepantleras (Keating 2006), who are in in-between spaces of “chaos” (Anzaldúa 2002, p. 548) that come to place at once, have to “dis-identify with existing beliefs, social structures, and models of identity … to transform” (Keating 2006, p. 9).

Partial knowledge and the nepantla concept are relational, partial, and weaving with each other, giving me vision to look at the pictures in different positions and conceptualizations in this project. Specifically, these concepts think with me about historical events and memories and see double the layers of a message in each picture, situated in a larger social context. Bearing these concepts in mind, I am reminded that no “fixed” results or “perfect” picture will come out of this paper because the story will always come in the forms of partiality, in-between-ness, and thinkability in discussions. The “result,” therefore, is not in the form of “category” either because I prefer not to follow a colonizing way of doing research (Smith 1999). Rather, the results will appear in the forms of daily conversations, notes, collected partially from different spaces and times. Simply speaking, this paper is trying to stay away from an “academic” paper as much as possible so that the paper itself can keep the nature of storytelling which invites people to oscillate among the events of/with our family.

As we are ready to enter the conversations, I invite you to be physically and spiritually present with us. I invite you to liberate yourself from the restriction of language and physical space to sit still and simply listen with us. I appreciate your patience and empathy with this process of storytelling. This process cannot be rushed, cannot be westernized and academized. This process is all about presence and being. I will use present tense, a grammar structure I learned in an English as a Second Language (ESL) class when I was in Vietnam, in this space because I want to stay focused on the being-ness of the present moment. I hope you, the readers, will find parts of your stories within ours, and then find your own “enlightened freedom” after leaving this space (Nhất Hạnh 1999).

3. Sitting

3.1. 1970–1994

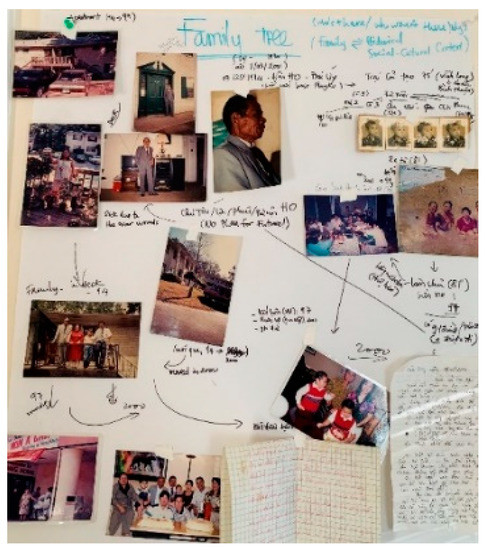

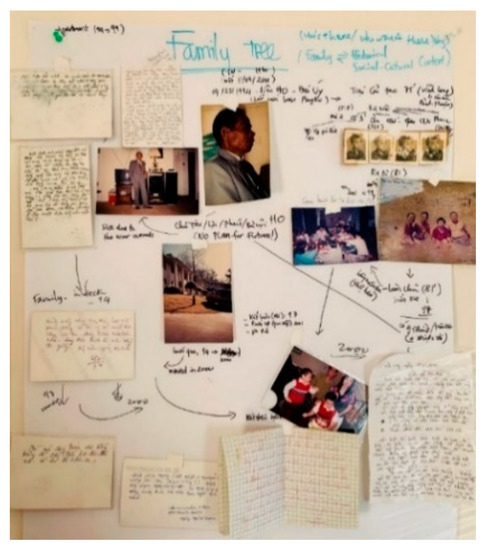

“Dad, can you please tell me about grandpa? I am always curious about him and I really want to know about his story.” I am talking to my dad while preparing photos to place on the floor. I am placing a portrait of grandpa at the top of the family tree (Figure 1) and listening to my dad. He states,

Figure 1.

It was a roller coaster of emotions and feelings for both of us in different ways. There were a lot of pauses and silences hidden in this family tree.

Your grandpa, or ông nội, was born in 1930 in a small town in Hanoi, capital of the North of Vietnam. He must have served in the U.S. military at the age of 18. He served as a colonel in the Vietnam war, and then he went to re-educational camps in 1975 in Vinh Long, a small town in Mekong Delta in Vietnam. The whole family settled down in Vinh Long until they went to the U.S. in 1994. As you know, he went there under the “HO” program. He passed away in 2001. I wished I could have come here earlier to see him before he was gone. Your uncles told me he kept asking them if I had been here, but unfortunately, due to paperwork, I could not make it here earlier.(Trinh (2019d), personal communication, 19 November 2019)

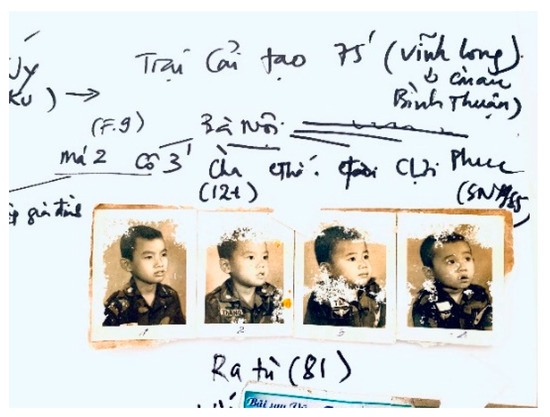

I find a photo (Figure 2) that intrigues my thinking. I ask, “Was it you, dad?”. He smiles,

Figure 2.

All my uncles, including my dad, were wearing military shirts when grandpa was still serving in the U.S. army.

Yes, it was me. Your grandpa got married in 1964, I was born at the end of that year. Four little boys wearing military shirts are your uncles. I come first in the photo because I am the eldest son of the family.(Trinh (2019d), personal communication, 19 November 2019)

My dad continues, “I would have joined the army, had the Vietnam war not been over. After the Vietnam war in 1975, your grandpa spent more than five years in re-education camps (1975–1981) before he was released”. (Trinh (2019d), personal communication, 19 November 2019)

“So, did you visit grandpa when he was in camps?”, I wonder. My dad says,

He was lucky to leave the camp; not many people did. While he was in camps, grandma had to work hard. She took all the jobs she could to bring food on the table; auntie 2 and auntie 3 had to do anything that came in hand. When I was 14 or 15, I went to see him with your grandma in a camp. I remember I was emotional. Your grandpa had pale skins. He looked tired and green. Not many people survived after the camp. Life in there was just different. After he left the camp in 1981, he came home without financial support; he was really sick, so I became the breadwinner who took over the responsibility of your grandma to help bring food on the table for younger siblings. I was 18 at that time.(Trinh (2019d), personal communication, 19 November 2019)

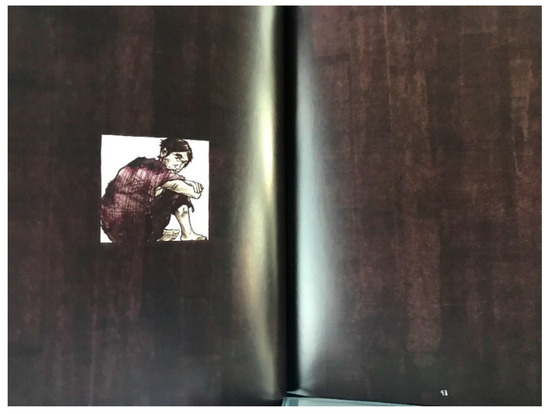

The silence takes over our conversation. I cannot imagine how hard life treated him and his back-then family when they struggled with the impacts of post-war challenges. A description of how my grandpa looked in the eyes of my dad has been partially depicted in a moment in a graphic memoir titled Vietnamerica by G.B. Tran (2010). Tran’s book describes a journey where he uncovers the roots and tragic history of his family and the stories behind his parents’ fleeing to the U.S. On page 93 of his memoir (Figure 3), he paints a picture where a “camper” was living. From this picture, I could imagine what the daily life of my grandpa looked like in a camp. There would be no lights in a tiny space, where my grandpa had to face loneliness, separation, and darkness for more than five years, or 1825 days, or 43,800 h. Life in a re-education camp exhausted a person, gradually killed their mind, body, soul, or any lights of hope that they could wish for. Reflecting on and connecting with this picture, my grandpa must have been fighting every day to look for a day to get his freedom back.

Figure 3.

A squared liminal space caged a person’s mind and soul without a light of hope.

In addition to in-camp experience, history also bears witness to other atrocities that (disabled) South Vietnamese veterans had to face post-camp, such as traumatic experiences and depression (for veterans) and class transitions (for veterans and their families). For example, Eikoh Ikul (2001) discusses the post-war public image of Vietnam war veterans who were “being looked upon as victims of this tragedy, whose families and friends had also suffered from the domestic conflict that surrounded it” (p. 47). In addition, Birman and Tran (2008) indicate that the camp detainees after the Vietnam war had experienced PTSD and depression, and were considered “as particularly at risk for the range of mental disorder” (p. 110). Further, Espiritu (2016) emphasizes South Vietnamese soldiers becoming “ghost soldiers” (p. 19), along with their families’ grief after the war, as the U.S. army left Vietnam, placing South Vietnamese soldiers as “mere puppets of U.S. imperialism, thereby erasing any legitimate position or human agency for South Vietnamese acting in contradictory ways in extremely complex realities of what was also a civil war in Vietnam” (p. 20). Historical contexts also witnessed the class transition of veterans and their families into “abject poverty” (Tran 2016, p. 34). Quan Tue Tran (2016) shares a story of a veteran who lost his legs:

After the war ended, disabled RVNMF (Republican of Vietnam military forces) veterans feel abandoned, uncertain about survival. We feel like children handicapped and orphaned at birth… In places outside Saigon, the communists have confiscated houses once built by the South Vietnamese government to compensate disabled veterans. In My Thoi village, disabled veterans had 24 h to vacate their homes. With nowhere to go, many went to Saigon, where they live on the streets, sleep in train stations, at bus stops, in market stalls, and in abandoned cemeteries … We organize ourselves into small groups and obtain incense sticks from the local temples to resell them on street corners and in alleys … There are many gravely disabled veterans who could not even sell incense. They have to beg on the streets.(p. 37)

Given the historical and political context in Vietnam after 1975, I can partially imagine and understand how hard grandpa and the whole family were struggling to fight against poverty and other psychological and emotional challenges in these difficult times. For me, our family were brave Nepantleras who were attempting to do their best to navigate through barriers in post-war situations.

As Anzaldúa (2002) acknowledges, “Nepantla, where the outer boundaries of the mind’s inner life meet the outer world of reality, is a zone of possibility. You experience reality as fluid, expanding, and contracting” (p. 544). My grandparents, my dad, and the whole family saw reality as “a zone of possibility” to do the best they could in order to support the family. For example, in addition to my aunties and grandma working to support younger children, my dad, after returning from the camp visit, decided to leave home for Cu Chi, a small town in the outskirts of Saigon at that time, to stay with uncle 8. He stayed there for three years for “vocational training,” in which the “school” was uncle 8′s repair shop. During his time of “training,” he sent home one or two letters every two months, with money attached each time. After that, he returned to Vinh Long, our hometown, to open his own shop when he was 18.

When my dad crashed into this post-war reality, he found he needed to shift his perspective, his social position as the eldest son of a colonel, to a working-class person to bring food to feed his younger brothers. He gave up his wish to join the army and took a job that he would never expect. He states, “I had no choice; either staying or leaving; if I had stayed, people would have died of hunger”. As a Nepantlera son, my dad chose to be in “isolation” (Keating 2006, p. 9) by leaving his hometown, his family and his three younger siblings, for financial purposes—for food security, to be more exact. As a Nepantlera, my dad chose “to dis-identify” with his social position to aim toward “transformation” (Keating 2006, p. 9) for his family, aimed towards a better life, or at least one that was something he could stick with. As I theorize and think about his present/past self, I can feel the pain that he carried back then.

In an autoethnography, in which I used walking meditation to guide me through the historical events (Trinh 2018), I used the act of hugging as a survival and learning tool to share my mom’s life events when my mom and I were in Vietnam. In that space, a hug with my mom communicates with me in different meanings: hugging is sensational; hugging is endurance; hugging is resistance; hugging is forgiveness; hugging is a bridge. As I was telling a story of my mom, I was critiquing the hegemonic patriarchy in Vietnam and the toxic masculinity that has existed in Vietnamese families. Specifically, I criticized and put hatred on my dad due to his domestic violence and abuse towards my mom and me when I was growing up in Vietnam. However, when I was meditatively walking to the end of the trail, I wished to build a bridge with my dad. I state, “I need to bridge the gap between my father and mother, and perhaps then bridge the gap between my father and me, too. I am done trying to be ‘man enough’ (Trinh 2018, p. 13). While writing about family histories in this space, the power of writing, thinking, theorizing, and connecting the family histories and events has brought me into the state of meditation and nepantla. As Keating (2006) states,

During nepantla, our worldviews and self-identities are shattered. Nepantla is painful, messy, confusing, and chaotic; it signals unexpected, uncontrollable shifts, transitions, and changes. Nepantla hurts!! But nepantla is also a time of self-reflection, choice, and potential growth—what Anzaldúa describes as opportunities to ‘see through’ restrictive cultural and personal scripts.(p. 9)

The personal growth, the “seeing-through” perspectives are enacted while I am writing this piece to see another truth, another partiality of my dad’s life and his decision for his family, grandparents and his younger siblings. I was not there to think with my dad. I was not there to understand him. I was just simply not there with him.

Further, I see and feel the images and experiences that my grandpa endured after leaving re-education camps. These stories were not shared or told by our family members until now, when I am doing this project. My perspectives are scattered into pieces. I need to pause to breathe due to uncontrollable shifts in understanding and configuration at the same time. My eyes drip with tears, for some reason. Nepantla, indeed, hurts, but this state witnesses a growth in my thinking, in my knowledge toward my family in a historically critical time.

3.2. 1994–2000

“Dad, my memories of grandpa are blurry”, I tell my dad when I am ready to continue the conversation with him. All of the memories about my grandpa are through the pictures that I have received since they moved to the U.S. in 1994. I was six at that time. In my memory, grandpa was thin, tall, wearing a grey suit and a red tie: that was it. My father told me that my grandpa was sponsored by the U.S. government to migrate to the U.S. in an “HO” program. But I figure out that the “HO” program that he kept mentioning was the “Humanitarian Operation” (HO) program. This program was in agreement between the United States and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam for the current and former detainees in re-education camps (Zhou and Bankston 2000).

As a former re-education camp detainee, my grandpa was eligible to apply for the program for his family to migrate to the U.S. (see more about the program and its different waves of migration in Nguyen 2020), except for my dad and my uncle Thang due to their marital statuses. Since my grandpa went to the U.S. in 1994, I did not have a chance to talk to him, although I was aware that our family received remittances from them a few times. I was not clear on how many times a year we received money, but my father never ceased to remind me of the value of the money that grandpa and uncles sent us. These reminders were regular during our meals back in Vietnam. I have always appreciated the money, but, more importantly, I looked for a conversation with my grandpa and their families to know the story behind the remittances.

Remittances, or money sent by immigrants to their family in the original country, have been repeatedly recalled for appreciation in our family’s conversations; however, this money has never been discussed in behind-the-scene stories. In a study exploring the relationship between masculinity and remittance in transnational immigrant families in the U.S., Hung Cam Thai (2006) describes Vietnam in 2004 as “ranked sixteenth among the top remittance-receiving countries worldwide and fifth among all Asian countries after India, China, Philippines, and Pakistan” (p. 250) from Viet Kieu, or overseas Vietnamese. Thai (2006) discusses the three main reasons behind sending remittance. One, this act is considered as a “status strategy” (p. 258) to maintain social and class position in the home country (i.e., Vietnam). Two, as remitters, the participants in this research are reported to have sent money to the family as “the most obligatory” act to the family in Vietnam (p. 258). The third reason is that this act is as such a promise of future return. Even though these remitters are viewed as “the heroes” (p. 255), the efforts were not shared by them to the receivers. Thai reports,

In this way, altruistic remitters are also least likely to tell their families about the hardships they endure in the United States when they send money; as such, these men are often the most frugal with their consumption the United States since they generally have the least disposable income after they account for remittances. Such men talk about sacrifices they make in their everyday lives so that they save all the money they could to send to family.(pp. 258–59)

These findings, somehow, reflect our family’s expectations when we were in Vietnam, or at least they are true to my memories and emotions when we were having dinner. I remember my dad telling me in our meals, “You need to appreciate money your uncles and grandparents sent to us. They worked really hard.” But “how hard” was never mentioned in our back-then conversation until I worked on this project.

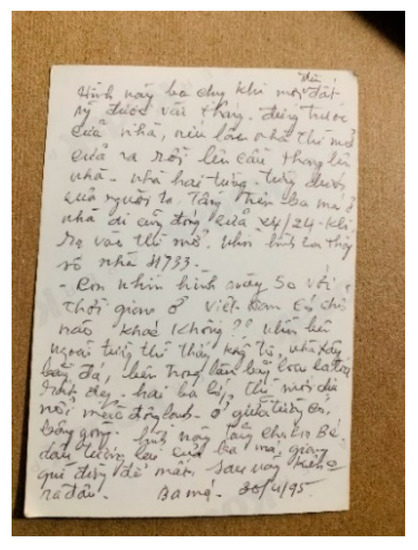

There are a few surprises that I found while I was tracing the history. One, the back of most of the photos witnesses my grandpa’s handwriting (Figure 4). These writings turn out to be astonishingly descriptive stories to me. In other words, my grandpa was a wonderful storyteller back then. He used photos to communicate with us, living in a homeland that he had to leave due to political repression.

Figure 4.

Each description tells a story that takes me and my dad back to the memories.

For example, on a photo (Figure 5), where my grandpa is standing in front of a blue door, he writes:

Figure 5.

A letter was written by my grandpa when he first came to the U.S.

This picture was taken when I first came to the U.S. I am standing in front of the house. Open the door, go upstairs, downstairs someone stay, we stay upstairs. Everyone closes the door 24/7. You can see the address 4733. Did you see any differences when we were in Vietnam? It was not clear if you look from outside. The house was made of bricks, inside was different kinds of bricks, which is beautiful. There should be two or three layers because the winter here is very cold. This picture was given for my future daughter-in-law. Keep it, don’t lose it, you cannot find it later. Your parents—04/30/1995.

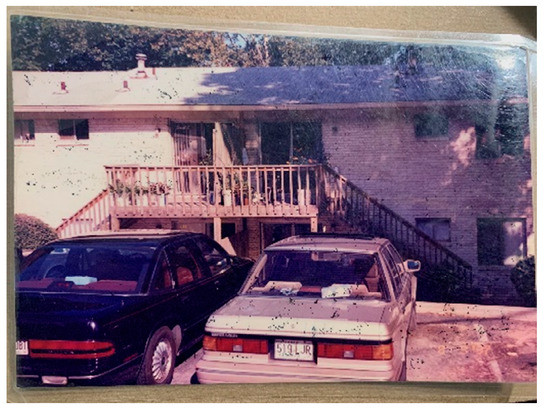

Another surprise is that my grandpa did not only take photos of his accommodation once; he took this kind of “theme” several times. Specifically, he took photos when he moved to a different apartment in 1994 and described the house in detail (Figure 6). The photo describes:

Figure 6.

Cars and a new place.

This is the back of the house. The gray car with the number 519112, it is L.’s. We have another car in the basement. The outside was made of bricks. There are three layers, so inside is warm. In the middle was wood, it is really warm in the winter.

I am getting stuck trying to understand why he took a lot of these photos; my dad did not explain them, either. As Harper (2002) reminds me, “Photo elicitation also comes from the collaboration it inspires. When two or more people discuss the meaning of photographs, they try to figure out something together” (p. 23). I therefore decide to find different ways to understand that question.

3.3. 2019

In our Vietnamese culture, we have a few mandatory events that we need to attend, such as đám giỗ (annual death anniversary), đám sinh nhật (birthday), đầy tháng (baby showers party), đón giao thừa (New Year Eve party), and so on. The events serve to maintain social connection and social capital (Taylor 2016), such as by sharing of stories to younger generations so that they can learn about family history. While we attend these events, we come together for nhậu. The act of nhậu is not simply eating and drinking, but it bears the meaning of family connection through sharing, back and forth, the histories of the past, the present, and the future. Alex Nguyen (n.d.) writes about nhậu in Vietnamese families beautifully as follows:

In the context of nhậu, I continue to honor the traditions, both old and new, of my parents at my own community gatherings. We, the next generation, gather to eat, to drink, to unpack our shared traumas and histories, and to bask in our collective love for our ancestors and heritage. In Vietnamese food, I find home; in Vietnamese community, I find love. At the nhậu table, every person has the opportunity to hold and be held. We bear witness to one another without fear of judgment or alienation. When we nhậu, we do so with the knowledge that there is no need for code-switching, explanations of cultural cues, or expected performances of identity. We drink and eat in safety, in kinship, and in liberation.(para. 7)

As a child born and raised in Mekong Delta, in the South of Vietnam, I found this description to be precise, authentic, and beautiful in a way that only Vietnamese can understand within the importance of these moments at a “nhậu” table. Tonight, at đón giao thừa, where we come together to celebrate a new year, I was curious about the accommodation when grandpa and my uncles first came to the U.S. I ask, “Can you please share with me where you lived when you first came to the U.S.?” Uncle P., the youngest brother, excitedly shares with me:

Ok, if you want to know. When we first came here, we had to live in a subsidized apartment in Tucker. The rooms were not really spacious, but our brothers could manage to save a room for ba má (parents). At that time, anh T. (brother T.) and anh L. (brother L.) had to work multiple jobs at the same time.(Trinh (2019e), personal communication, 31 December 2019)

Uncle T. continues:

At that time, P. was young, so I had to take care of family. I signed up to work in a factory where I am currently working now. It has been more than 20 years so far. I worked whatever shifts that they gave me so I could keep my job.(Trinh (2019e), personal communication, 31 December 2019)

Then, uncle L. shares:

At that time, we did not have GPS. Do you still remember there was a day that we had to ask for police to come help us and drive us home, T.? We did not know much English there; there was no GPS like iPhone right now; we used maps instead. There were some nights that it was too dark; I had to work a late shift, so I could not come home early. I needed to sleep more than anything, but I needed money to take care of family and I needed money for marriage.(Trinh (2019e), personal communication, 31 December 2019)

Uncle T. continues, “Right, P. was young at that time, but he helped with interpretation when dad was in the hospital and later for mom as well” (Trinh (2019e), personal communication, 31 December 2019). My dad is attentively listening to the conversation.

The conversation about accommodation has turned into something interesting: their real lives when they first came to the U.S. in the first 10 years (1994–2004). They did not talk much about remittance; they did not even talk about the “heroic” image or sacrifices. Instead, they shared the stories of their lives. In Straddling two social worlds: The Experience of Vietnamese Refugee Children in the United States written by Zhou and Bankston (2000), I learned that since 1990, Vietnamese political detainees and their families in the U.S. were struggling “below the poverty line” (p. 20). The authors state, “Their [Vietnamese families] economic gains have come by virtue of hard work and cooperation. The 1990 Census reported that more than one out of every five Vietnamese families contained three or more workers” (p. 20). This information precisely speaks the truth of the hardship that Vietnamese immigrant families faced when they first came to this country, which relates to the mundane stories shared by my uncles at a nhậu table. My uncles are storytellers who depicted a picture of those who crossed the borders of language, culture, society, job-seeking when they were transitioning to overcome poverty at their best. They served as bridgers/Nepantleras/agents of awakening (Keating 2006, p. 9) for my grandparents so that each of them could connect and inspire each other in a new life and in a new society. They continuously remind each other of “deep awareness” (Keating 2006, p. 9) of so-called “responsibilities.” Through these mundane stories, they have inspired me (and probably my father, despite his silence at the table), in the silent work and sacrifices that they did not state in the letters or photos or remittances sent back to Vietnam. The partiality of their stories brought me back to the history, helping me bear witness to the history and their struggles in transition between two countries, so that I can now understand “how hard” it was behind the money we received when we were in Vietnam. The stories were untold and hidden, but they were never too late to unfold and discover.

4. Re-Positioning

Even though the conversations with my dad and uncles occurred in different unscholarly settings, they did give me a different sense of how I want to re-position myself in future scholarly work. The notion of knowledge shared and collected partially throughout this project hits me hard when I reach this step. Specifically, Haraway (1988) reminds me about the practice of objectivity in research, in which we are “bound to seek perspective from those points of view, which can never be known in advance, that promise something quite extraordinary, that is, knowledge potent for constructing worlds less organized by axes of domination” (p. 585). Haraway’s argument brings me to the in-between state and inspires me to think critically about my positionality as a researcher, which I will explain shortly.

One, I remind myself that I am not romanticizing the historical events, but I am letting the truth speak for itself. Two, the knowledge itself is contested and located in different perspectives, and I will be unable to look for a fixed answer to a specific question. I let the story speak and lead its own way towards something extraordinary so I can learn, interrogate, and (re)position from it. Anzaldúa and Keating (2009) contend, “The past is hanging behind glass. We, the viewers in the present, walk around and around the glass-boxed past. I wonder who I used to be, I wonder who I am” (pp. 182–83). Therefore, my family’s past events have taken me on a tour on the roller coaster of emotions and feelings, which I am intrigued and thrilled to continue to discover, personally and professionally.

For the question of who I am as a Vietnamese, it will probably take a longer time to discover and find an answer, or, at least, the answer will come in the form of continuity and unfixity that awaits me with different knowledge and extraordinary moments at future family events. “What does it mean to be Vietnamese? And how does Vietnamese-ness look?” would be finding the answers in different forms, different spaces and times; those answers could be hidden in the family photos, in the conversations, at a nhậu table, or somewhere else. But I am pretty sure of one thing: that Vietnamese-ness does not travel any farther; it is already within us, the children of the homeland so-called Vietnam, regardless of how far we go, of how long we have not come back, or of what names we put in a certificate of naturalization.

For the question of who I am as a Vietnamese educational researcher, I will need to borrow a beautiful and provoking question from Sleeter (2008): “Given who we are and where we came from, how do we proceed from here?” (p. 122). I would like to follow this thought and raise another question, “Given who we think we are and where we come from, how can we go back to let the history speak for itself?”. While conducting this personal project, I am thinking about how the reader can fully understand different historical events that I only show partially in this small space. I am wondering to what extent I can fully present the wholeness of my family’s struggles, emotions, and feelings in the historical and cultural context. I do not think I can do that in this liminal space. However, what I am convinced that I have successfully done (as a researcher, a storyteller, a Vietnamese immigrant child) is that I have opened possibilities for future Vietnamese researchers and other genealogical researchers who want to find untold partial stories behind family photos without falling into the rigidity of an academic paper, as this paper is published and reaches out to international readers. Haraway (1988) claims that subjectivity of research is “multidimensional” (p. 586), and so is vision. The notion of vision, or seeing, is partial, interrelated, “complex and contradictory” (p. 589). She states, “Vision is always a question of the power to see—and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualizing practices. With whose blood were my eyes crafted? These points also apply to testimony from the position of ‘oneself’ (p. 585, emphasis in original). From this perspective, I do think my vision, my positionality in this project, and my eyes to read and re-read the stories are always coming into a form of continuity, explorability and interrelativity among/within different, but inter-related, past and present events. I appreciate readers when you patiently and slowly re-read (Britzman 1995; Kumashiro 2002) our stories so that you can see and hear the voice of our family through pieces of information and photos across spaces and times.

5. Walking Out

I am walking back to my car and am ready to go home. We have been “coming in,” “walking,” “sitting,” “drinking and eating,” and “traveling” together in this historical journey through my meditating walk (Trinh 2018, 2020a). I understand when we moved in between and among spaces and times, you felt confused about the so-called “logic” behind the storyline. First of all, I am grateful for your patience with me in this walk. Second, I would like you to know that I am sharing my childhood experience with you as I have learned and remembered how the folk stories were told by my mom and grandmas when I was a child. As I stated earlier, the process of storytelling cannot be rushed, cannot be westernized and academized. This story might read as “confused” to you, but I would like it to be told in a Vietnamese way as I made a promise to my grandparents when I first walked in.

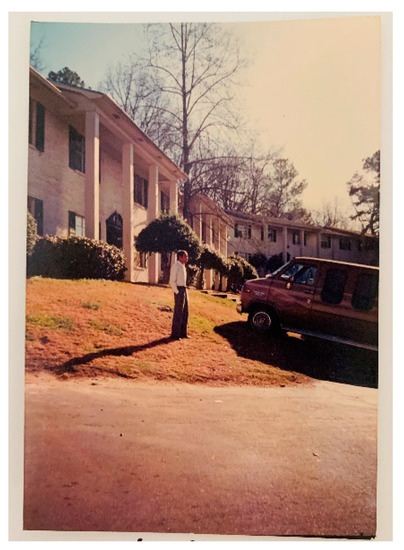

This project is a continuity of my “coming home” project in academic papers. I have come home as a child who survived from domestic violence abuse (Trinh 2018) as a Chicana feminist researcher (Trinh 2020c, Trinh and Merino forthcoming), as a decolonial writer (Trinh 2019b, 2019c, 2020b) and a decolonial teacher (Kasun et al. 2019), and recently as a queer Nepantlera (Trinh 2019a, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c). This space is a homecoming as a Vietnamese immigrant grandchild. In this space, I am coming home to Vietnam, to our hometown Vinh Long, where my parents and I were having dinner together. In our meals, my dad told me about the importance of building a house and of creating a homey space in Vietnamese culture. A house for Vietnamese families is a representation of certainty, foundation, and assurance. And now, when all the small details are coming back, I come to understand why grandpa took a lot of photos of his accommodation; because he wanted to show that they had a place, a settlement in the U.S. He wanted us, his grandchildren and children in Vietnam, to rest assured that they already had a “good” life in a strange country, even though they had to face issues of poverty and other atrocities in transition. Back in Vinh Long, our family had to live in a stilt house lining the steep bank for 20 years, which could collapse at any time. Therefore, having a house in which to settle down is a dream for every person in our family, including my grandpa. Therefore, my grandpa was careful in choosing a picture to send his message: “We are safe here!”. Now, I understand. I come to understand that no matter how far or no matter where a father goes, his love and care are still with his children. Even though my grandpa no longer serves in the army, he is a hero to me, and so are grandma, dad, and uncles. Family love is just that simple: spaceless, unconditional and immortal.

I am walking closer to where my grandparents are resting. The wise words about the nature of death by Thầy Thích Nhat Hanh (2002) echo in my ears:

Pay attention to all the leaves, the flowers, the birds and the dewdrops. If you can stop and look deeply, you will be able to recognize your beloved one manifesting again and again in many forms. You will again embrace the joy of life.(p. 7)

According to Thầy, when someone dies, they are still with us, but in a different form. These forms manifest in our everyday life. In this case, the photos, the stories, the handwriting, the spirits of my grandparents are still living within us, the living (grand)children. “Memory as a gift of freedom” (Bui 2018, p. 67), you might say. For me, at this moment, I am breathing in the freedom that my ancestors have built up for me. I was raised and will continue to grow through history, and I am still a Vietnamese child whenever I go. As I walk towards my grandparents, I recall a photo (Figure 7) in the family tree where my grandpa was sunbathing in front of his apartment. Spending five years in re-education camps made him appreciate the warmth of sunlight and the warmth of freedom. I am walking close to him and I am looking forward to a future conversation with him about his life in the camps. That conversation will happen in another space and time.

Figure 7.

A day in my grandpa’s life in the U.S. in 1994.

The birds are still chirping, exactly like when I first came in. The oak leaves are falling, but they promise new life being born. I am walking out of the space, wondering if I have finished my project and answered the questions I asked at the beginning. I still do not have a final, fixed answer to those questions, but I will let these ideas sit alone for a while and will revisit them another time. Today is Memorial Day. I leave my grandparents’ place in peace. They are resting in peace, but they always continue to keep an eye on their offspring, to see where we go and the never-ending stories that continue to be written.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Thank you, grandparents and uncles. Your letters, photos, and mundane stories at a nhậu table inspired me to write this piece. Thank you, Caroline King and Lisa McLeod-Chambless, for proofreading and sharing your thoughts about this paper with me.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anzaldúa, G. 2002. Now let us shift...the path of conocimiento..inner work, public acts. In This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformations. Edited by G. Anzaldúa and A. Keating. New York: Routledge, pp. 540–78. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, G., and A. Keating. 2009. The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader. Durham: Durham Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birman, Dina, and Nellie Tran. 2008. Psychological distress and adjustment of Vietnamese refugees in the United States: Association with pre- and postmigration factors. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 78: 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, Alice, and Shirin Hirsch. 2018. Inter-generational transnationalism: The impact of refugee backgrounds on second generation. Comparative Migration Studies 6: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britzman, D. P. 1995. Is there a queer pedagogy? Or, stop reading straight. Educational Theory 45: 151–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Long T. 2018. Returns of War: South Vietnam and the Price of Refugee Memory. In Nation of Nations: Immigrant History as American History. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J., and M. Collier. 1986. Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovich, A. 2012. Depression: A Public Feeling. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu, Yen Le, and Thom Tran. 2002. "Việt Nam, Nước tôi" (Vietnam, my country): Vietnamese Americans and transnationalism. In The Changing Face of Home: The Transnational Lives of the Second Generation. Edited by Peggy Levitt and Mary C. Waters. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 367–98. [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu, Yen Le. 2016. Vietnamese refugees and internet memorials: When does war end and who gets to decide? In Looking Back on the Vietnam War: Twenty-First-Century Perspectives. Edited by Brenda M. Boyle and Jeehyun Lim. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies 14: 575–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D. 2002. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies 17: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikul, Eikoh. 2001. Reprogramming Memories: The Historicization of the Vietnam War from the 1970s through the 1990s. Japanese Journal of American Studies 12: 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kasun, Sue G., Ethan Trinh, and Brittney Caldwell. 2019. Decolonizing identities of teachers of color through study abroad: Dreaming beyond assumptions, toward embracing transnational ways of knowing. In Redefining Teaching Competence through Immersive Program. Edited by D. Martin and E. Smolcic. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 207–33. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, A. 2006. From borderlands and new mestizas to nepantlas and nepantleras: Anzaldúan theories for social change. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 4: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kumashiro, K. 2002. Troubling Education: ‘Queer’ Activism and Anti-Oppressive Pedagogy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Alex. n.d. In food and community: How Vietnamese drinking culture taught me to love my queerness. Colorbbq. Available online: https://www.colorbloq.org/in-food-and-community-how-vietnamese-drinking-culture-taught-me-to-love-my-queerness (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Nguyen, D. 2019. Transnational Vietnamese: Language practices, new literacies, and redefinition of the “American dream”. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education & Advancement 14: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Nguyen Le Hanh. 2020. The process to rapprochement between Vietnam and its diaspora in the United States. Diaspora Studies 13: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhất Hạnh, Thích. 1999. Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers. New York: Riverhead Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nhat Hanh, Thích. 2002. No Death, no Fear: Comforting Wisdom for Life. New York: Riverhead Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nhat Hanh, Thích. 2015. How to Walk. Berkeley: Parallax Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Joan Wallach. 1992. Experience. In Feminists Theorize the Political. Edited by Judith Butler and Joan Wallach Scott. New York: Routledge, pp. 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeter, Christine. 2008. Critical family history, identity, and historical memory. Educational Studies 43: 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Philip. 2016. Connected and Disconnected in Viet Nam: Remaking Social Relations in a Post-Socialist Nation. Canberra: ANU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thai, Hung Cam. 2006. Money and masculinity among low wage Vietnamese immigrants in transnational families. International Journal of Sociology of the Family 32: 247–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, G. B. 2010. Vietnamerica: A Family’s Journey. New York: Villard Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Quan Tue. 2016. Broken, but not forsaken disabled South Vietnamese veterans in Vietnam and the Vietnamese diaspora. In Looking Back on the Vietnam War: Twenty-First-Century Perspectives. Edited by Brenda M. Boyle and Jeehyun Lim. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, Ethan. 2018. How hugging mom teaches me the meaning of love and perhaps beyond. Journal of Faith, Education, and Community 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, Ethan. 2019a. Breaking down the “Coatlicue state” to see a self: Queer voices within a circle. The Assembly: A Journal for Public Scholarship on Education 2: 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, Ethan. 2019b. Building a foundation of love: Let’s write toward compassion, connections, bridging and rebornness. Bridges 1: 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, Ethan. 2019c. From creative writing to a self’s liberation: A monologue of a struggling writer. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement 14: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, Ethan. 2019d. Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA. Personal communication, November.

- Trinh, Ethan. 2019e. Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA. Personal communication, December.

- Trinh, Ethan. 2020a. “Still you resist”: An autohistoria-teoria of a Vietnamese queer teacher to meditate, teach, and love in the Coatlicue state. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, Ethan. 2020b. Too Nepantlera to write: Building an inclusive tribalism for all. Camino Real Journal 12: 213–22. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, Ethan. 2020c. Suicide and Nepantla: Writing in in-between space to crave policy change. LGBTQ Policy Journal 10: 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, Ethan, and L. J. Pentón Herrera. Forthcoming. Writing as an art of rebellion: Scholars of color using literacy to find spaces of identity and belonging in academia. In Amplified Voices, Intersecting Identities: First-Generation PhDs Navigating Institutional Power. Edited by J. Sablan and J. Van Galen. Boston: Sense Publisher.

- Trinh, E., and L. Merino. Forthcoming. Bridge building through duoethnographies: Stories of Nepantleras in a land of liberation. In Autoethnographies in ELT: Transnational Identities, Pedagogies, and Practices. Edited by B. Yazan, R. Jain and C. Canagarajah. New York: Routlege.

- Zhou, Min, and Carl Bankston. 2000. Straddling two social worlds: The Experience of Vietnamese Refugee Children in the United States. New York: Eric Clearinghouse on Urban Education, pp. 1–93. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).