1. Introduction

Ení bá fi ojú àná woòkú

Ebora a bó láso

Meaning:

The above aphorism is a laconic saying among the Yorùbá that reflects their core belief and worldview about the transformational powers of death (

ikú). ‘Death’ is a transition from the present life to the afterlife, a simple continuation of life here. However, during this transformation, the dead person is believed to possess superhuman powers, capable of affecting, positively or negatively, people who are still alive. The powers attributed to the dead among the Yorùbá people of southwestern Nigeria are akin to those of deities. Indeed, there are instances

1 in Yorùbá history where dead ancestors (

alálè or

babańlá) have been transformed to deities and included in the Yoruba pantheon through the process of apotheosis. Owing to this belief, when an important and aged leader or personage in a family (

ìdílé) or community (

àwùjo/ìletò) dies, rather than consider that the person has been totally annihilated by death, he or she is believed to have moved from our realm of existence to a higher one. He or she is said to have joined the ancestors in the other world. Here, ancestors refer to dead relations which by inference and membership of the same community are linked to the very founders (

alálè)

2, rulers and eminent personages of the family or the community to which the dead person belonged while alive. The long dead ancestors, some of whom may be remembered faintly or not at all, are called the

baba ńlá (our fore fathers). Although

alálè literally translates to ‘the owners of the land’, it may also mean ‘those who belong to the ground’ or ‘those who have been committed to the ground’. However, in its usage,

alálè refers to the original founders and successive leaders of a community since its inception. Such ancestors are believed to continue their existence in the ‘other world’ (spiritual world), and they hold the responsibility of watching over members of the community which they founded, fostering the continued existence of their community based on the very principles of its founding. By virtue of their transition to the next world, they are believed to have been transformed into

abara méjì3 or

ebora,

4 thus possessing super human powers to ensure the continuous communal existence in the world of the living. For this reason, it is common among the Òyó-Yorùbá people, when a person dies to hear them exclaim:

Meaning:

He/She has gone to where the aged go (not admitting annihilation)

He/She has eaten bean-cake from a spiritual being

He has become a goat that eats around the homestead

He has become like the sheep, roam about

He/She has been transformed into a spirit being, loitering around and hunting for food around his homestead.

Baba Awo Ojebode

5 points out that the frequent mention of the dead loitering around his homestead in Òyó community is borne out of the conviction that the spirit of a deceased ancestor loiters around its people, watching over them. An expansion of this belief is that the spirit of the dead can directly influence the affairs of the living (

Morton-Williams 1960). Since these spirits are capable of being benevolent or malevolent to the living, they are venerated in order to keep them at peace with the living. Venerating the spirits of the dead is of utmost importance among the Yorùbá people of Òyó and, indeed, many African communities.

According to Baba Awo Agboola Famoriyo,

6 there have been instances where Ifá devotees or worshippers of other Yorùbá religion deities, on consultation with Ifá, were asked to make sacrifices to their dead ancestors in order to gain their blessings and get things going right. Another instance cited by Ojebode is that when family issues get incredibly controversial, the physical manifestation (

egúngún) of particular ancestors who are considered knowledgeable about the issues in question are sought. These examples indicate that there is regular communion with the spirit of the dead among the Yorùbá. It is evident from such cases that the veneration of dead ancestors is common to all traditional Yorùbá people, immaterial of other deities they worship or religious belief they hold. The belief in life after death and veneration of dead ancestors are part and parcel of the people.

There are several mythological narratives on the origin of

egúngún among the Yorùbá.

Bascom (

1944) recorded one of such oral tradition. According to him, long ago,

Ikú and his followers regularly invaded

ojà Ifè (Ifè market) at Ilé-Ifè, and each time they came, they killed many people. The people sought the help of Oni Lafogido, the then king of Ifè, but he could not help. Finally, one Amaiyegun promised to help the people. Amaiyegun made a colorful costume for himself that fully covered his body such that no part was exposed, thereby disguising him. When he wore the costume, he could no longer be recognized. And when he stretched out his leg, the people sang

ẹwo ẹsè awo rébété rébété (come and see the beautiful leg of a masquerade) and, on stretching out his hands, they sang

ẹwo ọwó awo rébété rébété (come and see the beautiful hand of a masquerade). On the next market day, Amaiyegun and his followers, dressed in similar costumes, attacked

Ikú. The fact that

Ikú and his messengers could no longer recognize their attackers caused Amaiyegun to disarm them and drive them away. This account, according to Bascom, is man’s attempt to overcome death.

Lawal (

1977) submitted that the

egúngún culture of the Yorùbá is a way to harness the power of departed souls for the benefit of the living. For this reason, shrines are built for the departed where they are venerated. In such altars, sculptures are placed to house the souls of the dead. Lawal linked the Yorùbá belief in the independent existence of the soul to their other belief in surrogate twin figures. He stated that the spirit of a dead twin can be invoked into the surrogate and is kept there in order that the spirit will not torment the living twin. He opined that the soul of the dead would imperceptibly inhabit the sculpture, receiving sacrifices and blessing the living. The

egúngún mask is, therefore, a medium through which the souls of departed ancestors return to earth in physical forms to inquire about the welfare of their living descendants.

This robust Yorùbá belief in life after death is most evident in the Yorùbá

egúngún (

ará òrun) culture, a decidedly Yorùbá masking culture in which the spirits of long-dead ancestors manifest in bodily forms in visitations to the people they once knew and the community they once lived in while alive.

Oladimeji (

2001) points out that among the Yoruba, the union between the living and the dead is indissoluble. This belief and spiritual experience are also succinctly worded by

Morton-Williams (

1960):

The corollary of acknowledging the spirits of the dead is that the living do not become free of their influence. Their own freedom of action is constricted by the sanctions commanded by the watchful ancestors. But the dead are set at a distance and their power circumscribed by a series of rites.

It is important to note here that there is more than one type of masking culture among the Yorùbá. However, because all Yorùbá masking types are called

egúngún, there is a need for clarification. The

egúngún culture referred to in this study is the ancestral

egúngún. Ancestral

egúngún is a Yorùbá masking culture performed to honor the dead and serves as the physical appearance of dead ancestors. This is the same type of

egúngún defined by Babatunde Lawal as the ‘living dead’ (

Lawal 1977); by Henry Drewal (

Drewal 1978) as the

egúngún associated with the Òyó-Yorùbá in honoring dead ancestors and also distinguished by

Famule (

2017) as one that “emblematizes the spirit of the dead (aged) man, who is believed to have transformed into an ancestor.” In a study carried out by

Abokede (

2001), he observes that an

egúngún may not necessarily be representative of a particular spirit but the collective reincarnated forces of ancestors within a Yoruba community.

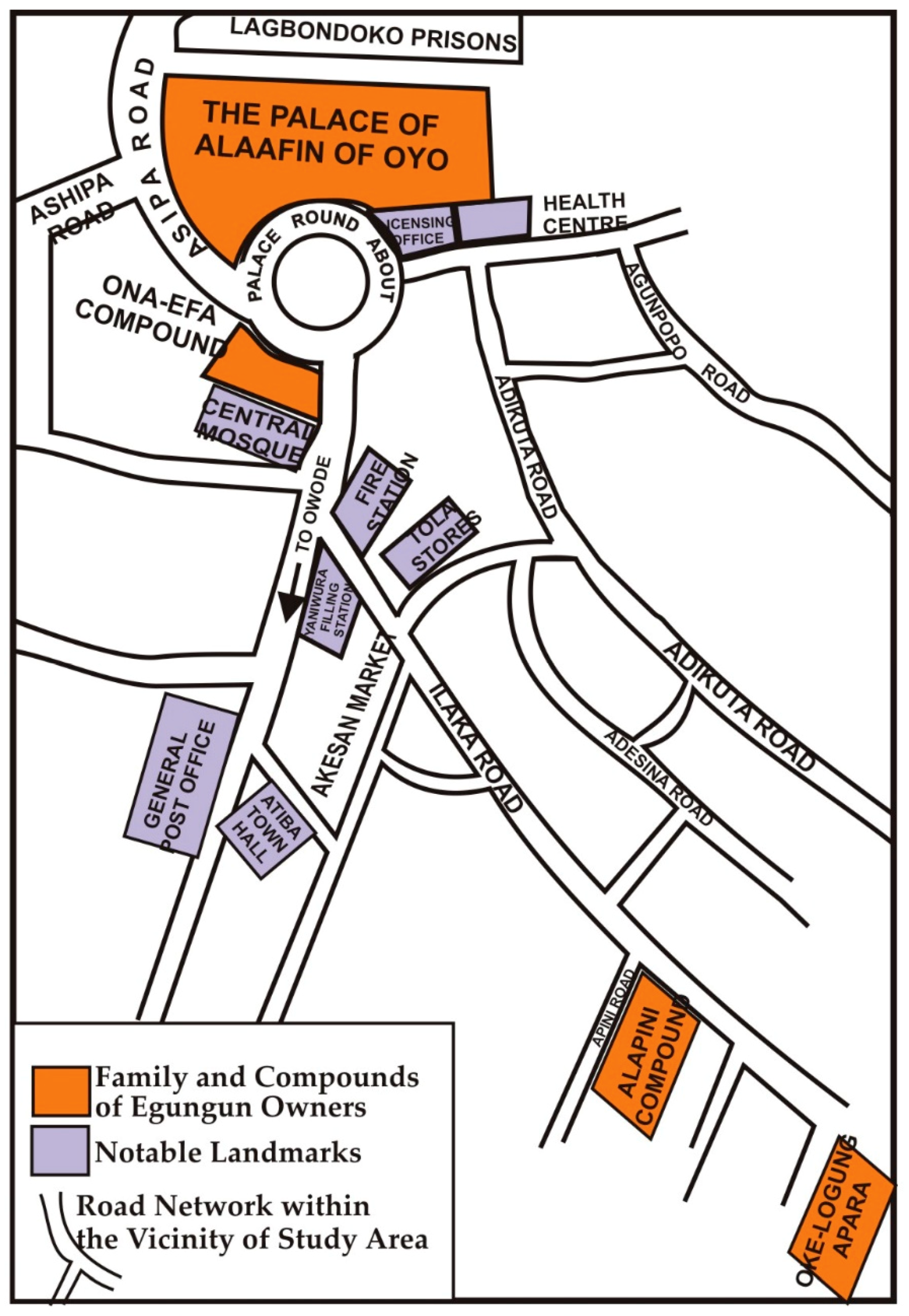

The present study is on the egúngún masking culture of two family compounds (ìdílé or agbo ilé) in Òyó town. The study was carried out between July and December 2018. In the ensuing discussions, the research will at different times employ the words ‘the dead’ and ‘ancestors’ interchangeably to refer to the spirit of the dead as manifested in egúngún.

The study looks into the practice of

egúngún masking culture in Òyó. Òyó is a central and foundational Yorùbá community. It boasts a sizeable number of ardent

egúngún worshipers. The present Òyó community (

Figure 1) is a resettlement town of Old Òyó,

7 an ancient Yorùbá kingdom that was initially situated up north in present Kwara State in Nigeria. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Old Òyó wielded the most powerful military and political power of all Yorùbá kingdoms (

Akinjogbin 1976). It conquered territories in Dahomey (now Benin Republic) and established Yorùbá communities as far away as Togo (

Akande 2015). At the decline of its power in the 19th century, it was sacked from its original location by the Fulani jihadists by the third decade of the century (

Ibiloye 2012). The Fulani jihadist were fundamentalist Islamic Fulani warriors led by Uthman dan Fodio, attacking communities and enforcing Islam on conquered territories in the northern parts of Nigeria and Cameroun in the early 19th century. After sacking Old Òyó, the inhabitants with their king (Alaafin Atiba) had to take refuge in their present location, previously called Àgó Òjá or Àgó d’Òyó. The presence of the people from Old Òyó has since over shadowed that of the autochthons. Altogether, they have formed a robust Yorùbá community, which in the present time is called Òyó, in line with the name of Old Òyó. Old Òyó itself was said to be established by Oranmiyan, a prince of Ilé-Ifè (

Babayemi 1979). Oranmiyan was the son of Oduduwa, the mythical progenitor of all Yorùbá people. The town according to Alaafin Lamidi Adeyemi III, the present ruler of Òyó, is the home of the most quintessential and preserved Yorùbá traditions, as brought down from Old Òyó by Alaafin Atiba, the king at the time of its relocation.

8 The present study therefore exemplifies a typical example of

egúngún practice among the Òyó-Yorùbá

9 people.

The practice of egúngún culture is quite strong among Òyó-Yorùbá people, especially the community in Òyó town, who interact with their ancestors with the utmost respect. Indeed, some Yorùbá ancestors have been deified through the process of apotheosis. Such ancestors include Sango (the thunder god), who is said to have once lived as a powerful man in Òyó. Mythology has it that after his death, he was deified and worshipped by his followers.

This study probes into the arts of two ancestral

egúngún in Òyó, namely

egúngún Mowuru of Oja Akesan and

egúngún Jeńjù of Apinni. The research which employs the ethnographic research design, identifies and analyzes specific artistic paraphernalia and performative acts of the

egúngún that are considered links, insinuating the genealogical connection between the living and the dead. The paper in essence probes how

egúngún masquerading establishes a link between the worlds of the living and the dead. Interrogation and exposition of the first-hand experiences of two personages

(eléégún), who have been directly involved in the actual masking of the

egúngún Mówúrú of Oja area and

egúngún Jéníjù of Apinni compound and 15 other stakeholders—some hold traditional

egúngún titles in Òyó town—were carried out. The stake holders interviewed include the current Alaafin of Òyó, His Imperial Majesty, Iku Baba Yeye, Lamidi Adeyemi III, and the Alapini of Òyó,

10 and Alhaji Sheu Rashid Ademola (the Alapini is a member of the Òyó Mesi

11 council). Also interviewed is Salawu Ibrahim, a personal assistant and court artist of the current Alaafin of Òyó; the Ona-Efa of Òyó, Chief Tajudeen Barika and Sarafa Awolola Ajakaye, a key informant (both men are the primary custodians of

egúngún Mowuru and its paraphernalia). Kehinde Abimbola, a babaláwo

12 and an associate of the Alapini, was equally interviewed. The paper attempts to locate the genealogical pedigree established by the masker to link the worlds of the living with that of the dead.

The assistance of a number of persons was sort in the course of this research. Mr. Johnson Ayinde, a lecturer at the Department of Fine Arts of Emmanuel Alayande College of Education, Oyo helped in booking appointments and locating the residences of leading egúngún worshippers and personages in Oyo. Mr. Salawu Ibrahim, also a lecturer at Emmanual Alayande College of Education and personal assistant to the Alaafin of Oyo helped in booking an appointment with the Alaafin. Toyese Oyee, as he is popularly called, at some points helped to man the video camera, especially on occasions when the researcher was busy photographing, writing or interviewing. Yemi Adebomi, a private freelance editor and language expert in Ibadan transcribed the voice interviews. It is important to mention that all the respondents, including the Alapini and Alaafin, consented to the publication of the information elicited in this research.

2. Ownership and Ancestral Spirit of Egúngún Jeńjù and Mowuru

Egúngún Jeńjù (see

Figure 1) belongs to the Alapini family. The family compound is where the highest ranking

egúngún chief is selected in Òyó.

13 Indeed, the name Alapini is the title of the highest

egúngún chief. The Alapini is the head of all

egúngún and is in charge of all

egúngún activities in the whole of Òyó town. The position of the Alapini is considered very important, so much so that the Alapini is a principal member of the Òyó-Mesi, the executive council of the Alaafin of Òyó.

Egúngún Jeńjù is a representative of the ancestors of the Alapini, and because of the position of the Alapini as the leader of all things

egúngún and as the owner of

egúngún Jeńjù, Jeńjù is undoubtedly a quintessential

egúngún in its paraphernalia and performance.

Jeńjù is said to be the head of all other

egúngún in Òyó. According to the Alapini, Alhaji Sheu Rashid Ademola,

14 the worship of Jeńjù has been an age-long tradition, and the forebears of the people in present-day Òyó brought it down from Old Òyó, their initial settlement. He narrated that when the people migrated from Old Òyó to their present location, Jeńjù did not follow them but Jeńjù suddenly emerged from nowhere after the people had settled down.

According to Alhaji Sheu Ademola,

15 when Jeńjù emerged at Òyó, Ifá oracular consultation was made and the spirit of the

egúngún, through Ifá, demanded to live at Oke-Ogbo, located at Oke-Logun, Apara. A point to note here is that Jeńjù is not domiciled in the family compound of the Alapini to which it belongs. A place was built for it at Oke-Logun, Apara (see

Figure 2), where its regalia and other paraphernalia of worship are kept. This location is also where it is venerated.

Although at the outset of this research, the Alapini, Alhaji Sheu Rashid Ademola, who is also the person in charge of worship of Jeńjù, claimed that Jeńjù is owned by the Alaafin and that he was just put in charge to care for it. In a later interview, Sarafa Ajakaiye claimed that it is only Mowuru that is directly owned by the Alaafin. This contradiction was cleared in a focused group discussion with the Alaafin.

16 In the presence of Alhaji Sheu Ademola and Safafa Ajakaiye, the Alaafin made it clear that Jeńjù belongs to the Alapini family and that Alhaji Sheu Ademola’s initial claim was borne out of the reason that it is the tradition of the Alaafin to supply material needs for the worship of Jeńjù. Alhaji Sheu Ademola’s claim was just to honor Alaafin. The Alaafin did not deny the direct ownership of Mowuru.

An important point that is worthy of note is that indigenes of Òyó are not allowed to mask as Jeńjù. A few days to the outing of Jeńjù, the Alapini and members of his compound would search for a stranger from another town, to wear the èkú. Invariably, almost at every outing, different persons are sought to mask. Such persons are paid money and materials in exchange for their services. Having established the ownership, custodian, domain, and masker of Jeńjù, we shall proceed to check the same with Mowuru.

Egúngún Mowuru (

Figure 3) is domiciled at the Ona-Efa compound (

Figure 2). Ona-Efa compound is located directly opposite the palace of Alaafin of Òyó. The

egúngún Mowuru and its paraphernalia are in the custody of Chief Ona-Efa, Mr. Tajudeen Barika. According to Sarafa Ajakaye, the Ona-Efa family comprises the domestic servants of the Alaafin. However, a key informant revealed to the researcher that the ancestry of the Ona-Efa family, in ancient times, from the outset were slaves of the Alaafin; although this was long before modernity. The title Ona-Efa is given to the head of the compound, which refers to the slaves of the Alaafin. The presence of

egúngún Mowuru in this family compound is, therefore, a mandate from the Alaafin. Chief Tajudeen Barika, the present Ona-Efa, being the head of the Alaafin’s domestic servants

17, is directly in charge.

It is usually assumed that the spirit of an egúngún is that of the ancestors of the family or compound to which it belongs. However, egúngún Mowuru is neither the ancestor of the Ona-Efa family, where it is domiciled, nor that of the Alaafin, the owner and worshipper. Egúngún Mowuru is the spirit of a long-dead ancestor of great warriors of Òyó. According to Sarafa Ajakaye, the spirit of Mowuru was invoked by the current Alaafin at a point in time as a result of a consultation with Ifá. He narrated the time in the history of the reigning Alaafin when he was faced with many political and spiritual enemies. The Alaafin consulted the Ifá oracle to find solutions to these problems. It was as a result of this consultation that Ifá recommended that the Alaafin should invoke and venerate the spirit of Mowuru. Mowuru was a renowned warrior of Old-Òyó; he was renowned for his many fights and victories for Old Òyó. His power for victories was therefore summoned and harnessed into the present egúngún Mowuru so that the Alaafin could overcome his challenges and enemies. The enemies of Alaafin, according to Sarafa Ajakaye, are those who oppose the personality of the Alaafin and those who are against the progress and wellbeing of the people of Òyó.

From the above narrative, it is essential to note that the ancestral spirit in an egúngún may not necessarily be that of any of the direct ancestors of the owner or worshippers. Also observed is that the special abilities or supernatural powers of a human being while alive can be summoned and reanimated after they are dead, as observed in the case of Mowuru. It is possible to invoke the spirits of the dead to harness and put to work the special abilities they had when they were alive.

A case of an ancestral spirit in

egúngún unrelated to its worshippers was narrated by Madam Niniola Abake Akande.

18 She told of a particular

egúngún in Ede, an ancient satellite town of Òyó. It was said that two young children went to the farm and on their way back home, they picked up two carved wooden dolls. They played with the dolls and took them home. When their parent found the dolls with them, they were made to return them to where they found them. Unfortunately, however, the dolls mysteriously kept returning and reappearing in their house, even before the children got back home from where they went to dispose of them. An Ifá priest was, therefore, consulted to unravel the mystery behind the enigmatic return of the dolls. The result of the divination was that the dolls were possessed by spirits who wished to be venerated and that the family had no choice other than to accept the dolls as objects of worship. The dolls were therefore sewn to an

èkú and were annually venerated as

egúngún. The family of the children was consequently mandated by Ifá to venerate these ‘unknown’ ancestors who came in the form of

egúngún. It was said that up to the present time, the

egúngún is still being worshipped. One of the praise songs for the

egúngún runs thus:

Meaning:

From the above, it is a ‘given’ that the egúngún may not necessarily represent the ancestors of the owner. Another intriguing fact about Mowuru is that the person that masks as egúngún Mowuru is not from the family compound of Ona-Efa, where the egúngún is domiciled nor from the family of Alaafin, its owner. Instead, a young man from neither family wears the eku. In such an instance, Mowuru, as an egúngún, is owned by the Alaafin, cared for by Alhaji Tajudeen Barika, of Ona-Efa compound and masked by a member of the Alagbure family; it can thus be said that egúngún Mowuru is indeed a community egúngún.

3. Connection through Constant Invocations, Sacrifices and Communal Worships of Jeńjù and Mowuru

According to the Alapini, Alhaji Chief Sheu Rasheed Ademola, two regular worships and sacrifices are made to the spirit of Jeńjù. The first is an every-5-day worship. On each occasion, Alhaji Ademola and two or more of his family members go to the

ìgbàlè19 and make propitiations in materials and edibles to Jeńjù. The materials offered include kola-nut, bean cake, dry gin, and at least one hen is killed. After the offerings, prayers are said to the spirit of Jeńjù. The monthly propitiation, however, involves a larger group from the family; the worship involves every available member of the Alapini family. During the worship, kola-nuts are cast

20 to inquire from the spirit of Jeńjù what would be required for the month’s worship. After the inquiry, provisions are made for the demands of Jeńjù, and the requirements are carried out. More often, these are in the forms of materials and edibles. The materials and edibles are sacrificed with, at least, a goat killed alongside many hens. After sacrifices and worship, there is usually eating and merriment in honour of and felicitation with the spirit of the ancestors.

The regular veneration of

egúngún Mowuru is slightly different from that of Jeńjù. Mowuru is venerated every 15 days with gin, hen, goat and moin-moin.

21 On the occasion of veneration, the spirit of Mowuru is invoked, and prayers are made to it for peace in the land of Òyó and, specifically, for Alaafin Oba Lamidi Adeyemi III to overcome all his challenges, and evil curses are said against all political enemies of the Alaafin. The warrior spirit of Mowuru is invoked to fight and kill such people. Occasionally, during the

oroorún22 (every 5 days) divination sessions for the Alaafin, there could be specific instruction by the Ifá priest that Mowuru should be venerated. Such worship does not necessarily have to tally with the usual 15-day worship. According to Sarafa Ajakaye,

23 one of the primary custodians of Mowuru, “I could be called upon, three times in 1 week to make sacrifices to the spirit of Mowuru; as many times as required”. Ajakaye pointed out that there are occasions when the Alaafin will be visited in a dream by some ancestors and may be commanded to carry out certain sacrifices for them—perhaps to spiritually attract victory for him in particular areas or on some issues. In the instance of such dreams, Mowuru will be venerated and sacrificed to.

It is important to note that at the outset of adoption of an ancestor for worship, the spirit of such an ancestor is invoked with the use of voice and incantations. Alhaji Sheu Ademola pointed out that voicing out the name of the spirits from time to time and making supplications to them is a significant aspect of worship. After invoking the spirit of the ancestor, it is then venerated with materials, edibles and, importantly, blood. The spirit is afterward charged with the responsibilities of guiding and protecting the people. To maintain the established relationship, however, continual veneration and prayers to the spirit and communal worship, such as the annual festivals, are compulsory. For instance, Alhaji Sheu Ademola pointed out that to sustain the presence of the invoked spirit of Jeńjù and, consequently, its potency, it is critical to make blood sacrifices of hens and goats as ingredients for worship.

4. Connexion Through Annual Festival Appearances and Communion of Jeńjù and Mowuru

As observed above, there could be reasons, ranging from oracular consultations to demand by the spirit of the

egúngún itself, to organise periodic communal worship. However, the annual

egúngún festival is a fixed affair. During the festival, the

egúngún will make a public appearance all over town, enjoying communal worship and re-association between the ancestors (the dead) and the people (the living). The annual

egúngún festival in Òyó usually falls within the month of August every year. The occasion is typically colorful for the entire people of Òyó, who often look forward to this festive period (see

Figure 4). The period is marked by the physical appearances of the various

egúngún from different family compounds. This event, apart from being a religious one, also adds social and recreational allure. Visitors to the palace square, where the

egúngún converge for performances, are usually on the lookout for which

egúngún will dance best. At the visit of the researcher to the last

egúngún festival (August 2018), there were discussions about which

egúngún danced best and had the most impressive regalia the previous year. Indeed, a much more modern perception of the outing festival of the

egúngún is more like a party. The indigenes of Òyó, home and abroad, converge for merriment. The period provides them with the opportunity to discuss matters that concern individual persons and the development of the Òyó community as a whole. The festival also attracts tourists, locals and foreigners, who wish to study the festival for reasons of research. The Alaafin, in his opening remarks to the 2018

egúngún Annual Festival,

24 pointed out that the coming together of Òyó people to re-associate with the spirits of their ancestors on an annual basis had been the reason for the peace and tranquility in the town, and that the spirits draw people from far and near to bless them.

The preparations for the annual public appearance, re-association and communal worship of the spirits of Jeńjù and Mowuru are germane to the establishment of a connection between the world of the living and that of the dead. Some activities carried out for the worship of the two egúngún are quite similar. However, we shall discuss that of Jeńjù first and then go on to discuss the peculiarities of Mowuru.

The very first preparation for Jeńjù’s outing is the scouting for the person who will mask. The person that will wear the eku of Jeńjù must be a stranger from another town. On a yearly basis, different persons have had to mask as Jeńjù. On locating a person, several sacrifices are made for his physical and spiritual protection. This masker will be paid with money and cloth for the job to be done.

After locating the masker, the next activity involves consultations with the spirits of the ancestors to know the procedures required for the year’s celebration. In the process, the spirit of Jeńjù is invoked through chanting, incantations, and pouring of libations with gin. A male goat is killed at the front of Ile-Ogbo,

25 and the masker will step on the blood of the goat and drink it. The masker will then be allowed into the

ìgbàlè, where he will stand on the stone of Jeńjù and say prayers for the king and people of the town. Afterward, he wears the

ekú and moves out of the

ìgbàlè wearing the full regalia of Jeńjù. At this point, the behaviour of the man is said to change because the spirit of Jeńjù would have engulfed him, and he would have become the actual Jeńjù. Chanters will start to sing praises of Jeńjù:

Je ń’gbó, Je ń’jù

Oko Àjé

Oko Osó

Oko Emèrè

Oba gbogbo Egúngún

Meaning:

After all the sacrifices and prayers are done, the masquerade then proceeds to dance around the town. The palace of the Alaafin is the point where all the egúngún converge. At the entrance of the palace, another goat is killed for Jeńjù. The masker egúngún will step on the blood and utter connecting prayers for the people, the town, and the king of Òyó. It then enters the palace square for the year’s performances, celebration and most importantly, communion.

The initial preparations for the public appearance of and communion of Mowuru with the people is an elaborate one; this is because, Mowuru as a masquerade, is unique. Because of its peculiarities discussed above, the preparations for its public appearance are intricate. By virtue of the position of the Mowuru to the Alaafin, being the Alaafin’s personal

egúngún, Mowuru will pay a courtesy visit to the Alaafin on the

òlògbò day.

26 On its visit, it will inform the Alaafin of the day of its outing and make known the sacrificial materials it desires. Mowuru will then pray for the Alaafin and then return to its

ìgbàlè.On the chosen day of its public outing, invocations and sacrifices are made to the spirit of Mowuru. The procedures of invocation and sacrifices are quite similar to that of Jeńjù as described above. In the process of its outing, some gesticulations and performances are symbolic and are relevant to the thrust of this study. Once Mowuru steps out of the ìgbàlè, the first action it takes is visiting the gravesides of the several Ona-Efa chiefs lined in front of the ìgbàlè. At the sides of each grave, Mowuru performs incantations and chanting.

When the

egúngún27 was interviewed, he recounted that he was invoking the spirits of dead ancestors in general through the spirits of the Ona-Efa in the graves. He pointed out that this action was an invitation to the long-dead ancestors to converge for worship and communion with the people of Òyó. He mentioned that in addition to inviting the ancestors, the

egúngún was also praying to the dead to take away to the other world every enemy of Òyó people and that of the Alaafin.

After the invocation and invitation of the ancestors, an earthen pot is then placed in front of Mowuru, and water is poured continuously into it while people chant:

Mowuru Àgbàkú olúàjà

Mowuru kò níkà nínú

Ò da omi gbígbóná sí omo è lára

Mowuru, órìn tomi tomi

Òrányàn, Ìbà re o

Oba Sàngó, Ìbà re o

Oba Àjàlá, Ìbà re o

Oba Adéníran, Ìbà re o

Adéyemí Àtàndá, Ikú Bàbá Yèyé, Ìbà re o

Gbogbo èyin Oba Òyó, Ìbàa yín

Ìbà èyin iwin tó te Òyó dó

Bi Mowuru semáa lo síta léèní

Gbogbo ohun ti Mowuru ba tite, Ategbe nio

Gbogbo aburú tó bá ńbò wá bá Làmídì Àtàndá omo Ìbírónké

Ojó tí omi bádà síiyò ló ńbàjé

Kítiwon ómáabàjéni

Ojo tí ìgbín bát’enu bo iyò

Ojo náà ni y’òkú

To ripe kìí san fún eésan

Kìíwò fún owò

Kòní san fún àwon òta Làmídì Àtàndá

Meaning:

Mowuru Agbaku, a king in a foreign land

Mowuru is not wicked

However, it poured hot water on its own child

Mowuru goes about with water

Homage to Oranyan (Alaafin of old)

Homage to Sango (Alaafin of old)

Homage to Ajala (Alaafin of old)

Homage to Adaniran (Alaafin of old)

Homage to Atanda, Iku Baba Yeye (the present Alaafin)

Homage to all the Alaafin of Òyó

Homage to the powers and forces that founded Òyó

As Mowuru is going out today

Whatever Mowuru does today, let all go unquestioned

All the evils that may be aimed at Lamidi Atanda (the present Alaafin) the son of Ibironke

The day that salt gets in contact with water, it dissolves

Let the enemies of the Alaafin be destroyed

The day that the snail gets in contact with salt

The snail will die the same day

Because the chaff of the palm kernel is never of any good use

The broom is never at peace

Let all the enemies of Òyó and Lamidi Atanda never find peace

As the chant is going on, Mowuru will use one of the two

kònkòsò, a one-sided axe in each hand (

Figure 5), to break the pot. After that, followers and adherents of Mowuru start to use their feet to march on the broken pot (

Figure 6), further breaking it into smaller pieces. This action, according to Tajudeen Barika,

28 is symbolic of Mowuru’s victory over the enemies of Òyó and the Alaafin.

From that point, Mowuru proceeds to the palace. At the entrance of the palace, before entering it, Mowuru sends a message to the Alaafin, asking for materials and goats to be sacrificed to the ancestors of the Alaafin. After this is done, the masquerade felicitates with the people with dance and jubilations. It is then that it enters the palace.

On entering the palace, Mowuru will first go to see the Alaafin to pray for him. It is important to note that Mowuru addresses the Alaafin by his first name, not adding a title or any form of respect appellation used for a king. According to Ajakaye, the spirit Mowuru is an ancestor and a contemporary of the great ancestors of the Alaafin; therefore, it cannot show the usual respect bestowed on kings by mere men. After the prayers for the Alaafin, Mowuru joins other egúngún at the palace square for communion, dancing, and felicitation with Òyó people.

5. Connection Through Paraphernalia

Jeńjù is a heavily cladded Òyó

egúngún. Its

èkú29 is made up of a gamut of cloth hanging from its head pad and flowing down to its legs. The cloths are made up of a variety of materials such as damask, velvet, satin, silk, and others (see

Figure 7). Mary Ann, Fitzgerald, Drewal and Okediji (

Fitzgerald et al. 1995, p. 54) have equally observed that the costume of egúngún is made of several layers of ‘cloth lappets’ of ‘expensive and prestigious textiles, expressing the wealth and status of a family as well as the power of the ancestors’. Another strong identification feature of Jeńjù is the load of objects (

erù ère) (see

Figure 8) on its head. It has on its head skulls of monkeys and chimpanzees, on the same flat wood surface are other carved objects that appear like charms and amulets. True, the

erù ère makes Jeńjù appear unique; it should be noted that

Kalilu (

1991) has warned that the images on

egúngún are less important to the very essence of the

egúngún cult.

Ère (mask), he suggests, are reflections of the affluence of the owner of the masquerade. However, in this case, the monkey skulls on Jeńjù are said to be symbolic of the traditional belief that Jeńjù can bring death to a witch or wizard.

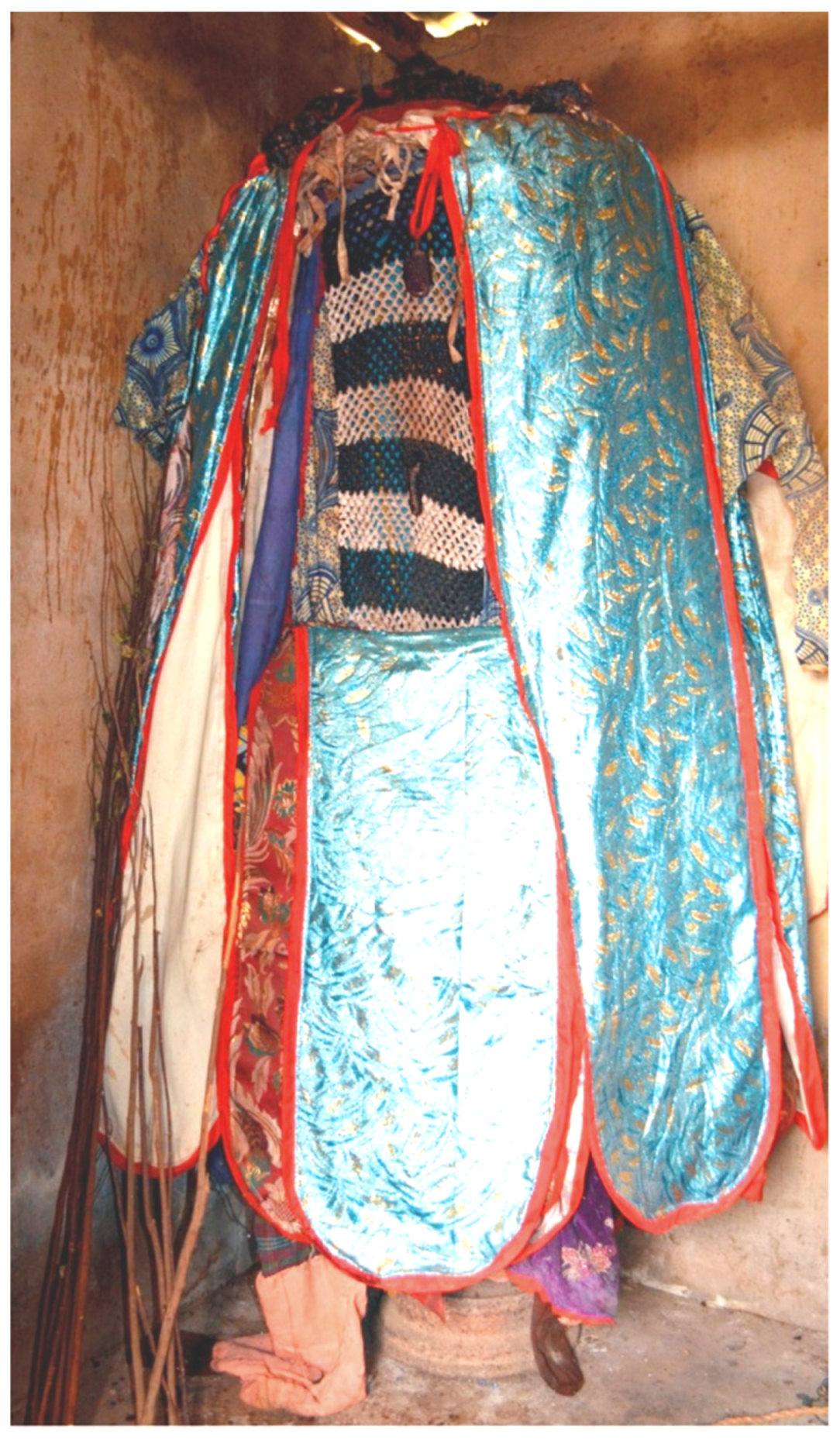

The

èkú of Mowuru appears like that of many other Yorùbá

egúngún. The

èkú is composed of a number of multicolored large strips of different clothing materials. The materials range from expensive damask cloth to cotton woven veils and off the shelf, cloth hem laces. Covering the face of the

egúngún is a loosely knitted woolen material that allows Mowuru enough breathing air and clear visibility. The cloth is, however, enough to hide the identity of the man behind the mask (

Figure 9). Around the neck of the

èkú, spreading to the belly button frontal part of the

egúngún is a large bib-like cloth decorated with dark blue and gold floral motifs. The bib-like material is taped around the hems with a red lace that has a zig-zag edge. The entire bib-like piece is placed over a larger white cloth that equally spreads from the neck to the lower part of the abdomen. Other materials on the

egúngún are large pleats of colorful clothing.

However, there is unique paraphernalia held at all times by Mowuru. The

egúngún wears white gloves and holds in its hands two

kònkòsò (narrow end, one-sided axes as shown in

Figure 5), one in each hand. According to the

egúngún, because Mowuru is an

egúngún of war, the

kònkòsò is an instrument of war, symbolically used to fight the enemies of Alaafin and the people of Òyó. The story is told that the

kònkòsò is the war tool favored by the original Mowuru and which the old Oyo warrior used during his many battles. Now that his spirit has engulfed the masker, he is wont to adopt similar behavior. As discussed above, when the

egúngún is about to come out for its public appearance, Mowuru uses the

kònkòsò to break the pot placed before him at the point of its stepping out of the

ìgbàlè. The action is symbolic of victories over the enemies of Alaafin and Òyó as a whole.

A close examination of the

èkú after the festival reveals two hidden parcels; one is sealed underneath the

èkú, right on top of the head of the

egúngún, while the other is underneath the cloth towards the chest. Tajudeen Barika pointed out that the parcels are Ifá literature and

ikin30 that instituted the worship of Mowuru. It is also these parcels that serve as a material link of the

èkú with the spirit of Mowuru. He explained that there is no amount of reworking and extemporizations on the

èkú that has ever affected the parcels. These two items (

Figure 10), he said, have been part of the

èkú from the very beginning of the adoption of the worship of Mowuru.

The èkú of egúngún is usually sewn by men who are called the Aláàrán. The Aláàrán are customarily selected from the family of eléégún. The sewing or restoration of èkú is, as a rule, done inside the ìgbàlè, because it is believed that the èkú is one of the secrets of egúngún. Indeed, women are forbidden from entering the ìgbàlè, so as not to know the secrets of egúngún. Although women are not involved in the dressing up of egúngún and the putting together of its paraphernalia, they are honored with the egúngún titles of Iya Àgan and Iya Mojè. These titles can only be bestowed on women who have attained the age of menopause. At this age, women are said to have become men. The duties of Iya Àgan and Iya Mojè as women leaders in the egúngún entourage are to accompany the egúngún during its outings and to chant and sing praises of the egúngún. A few women are also involved in minor decision making and chores. On no account are women allowed inside the ìgbàlè.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In the process of establishing the performative activities and paraphernalia of connection employed by Egúngún Jeńjù and Mowuru in linking the Òyó community with the spiritual world, some issues emerged.

The performative activities that institute connection and communing with the spirits of the egúngún share basic worship principles as obtained in some other religions. These activities include voicing out invocations, offering of materials, and in the case of egúngún worship, the spilling of blood as a sacrifice to the spirit of Jeńjù and Mowuru; all these are keys to cementing communion. Also, the consistent and constant veneration of the spirits of egúngún Jeńjù and Mowuru from time to time are equally important. At the annual festivals, the spirits of the egúngún are celebrated and made to pray and felicitate with the people of the community. At these festivals, the spiritual powers of the ancestors are harnessed for the physical and spiritual wellbeing of the Òyó community. All these and much more, make the egúngún force a compendium of beliefs and actions in harnessing the spiritual powers of the ancestors for the benefit of the living.

Another observation that emerged from the study is that it is usually taken for granted that all egúngún reside in the family compound of their owners, and that the spirit of the egúngún is always that of the ancestor of the worshippers and the family compound where it is domiciled. All these assumptions apply to many egúngún, but in the present research, all have been demonstrated not to be so, at least, not at all times. For instance, Egúngún Mowuru, which is owned by the Alaafin Lamidi Adeyemi III, is placed in the family compound of the Ona-Efa. Though venerated by the Ona-Efa family, the masker of the egúngún is from Ile-Alagbure. Another case is that of egúngún Jeńjù, the egúngún is domiciled at Oke-Logun, and its mask can only be worn by a total stranger to the community.

All these observations are pointers to the very essence of egúngún as a community religion and a unifying force of the people.

A very fundamental belief on which the worship of egúngún depends on, is the preservation of the lofty ideals upon which the community was founded. It is to conserve peaceful co-existence and communal living as intended by the founders (alálè). As much as these ideals are jealously guarded, undesirable elements cannot but exist within human societies. Such persons are usually potential threats to the tenets of the founding of the community and its communal co-existence. In traditional times, such persons were safely taken care of by the forces of egúngún.

According to Alhaji Sheu Ademola, such persona non grata are eliminated by Jeńjù. He also said that in traditional times, Jeńjù could be unleashed to eliminate a witch or wizard, as indicated in its above praise poem. Alhaji Sheu Ademola observed that the fact that the egúngún can no longer perform such a militant role is an indication of modernity in the worship of egúngún. This assertion is also found in a statement made by Alaafin Oba Lamidi Adeyemi, when he pointed out that the egúngún culture was established for the bonding of communities and to take care of too radically-minded people.

The Alaafin also pointed out that what informed the Yorùbá belief in egúngún is their worldview of ‘duality’. The duality of positive and negative; physical and spiritual. He observed that because a physical world exists, the Yoruba, therefore, believe that a spiritual one also exists. He pointed out that the things that happen in the physical world are predetermined in the spiritual world. For these reasons, the Òyó-Yorùbá people have, in times past, employed egúngún as a medium of positive communication to affect the supernatural to benefit the physical. By implication, the worship of egúngún by the Yorùbá people is a connecting bridge between two realms of existence, with the aim of maintaining equilibrium and, consequently, ontological balance.