1. 2017

I’m in The Lass, talking to a young woman. She’s a hardline feminist—it is the first thing she told me about herself. We are bemoaning inequality. In the wider world. Not here, not in Newcastle. I should say she is bemoaning and I am nodding in agreement, because I am missing twenty percent of what she is saying. The punk band is loud and we are sitting near the speakers, so close that I mistake the vibration of the bass line for the phone in my bag. She tells me that the first thing she asks a prospective partner is whether he agrees with a woman’s right to choose. If he does not, there is nothing more to say. I think there is so much more to say but I cannot go into that right now, the music is too loud, and she is on a roll. When she stops for breath I tell her I need to dance, but in truth I need to think. For now though, it is dancing only with all the other intoxicated locals. It is a sad night, a year since Tommy Ninefingers died, and the band is playing his songs. It is making the men a bit crazy. They need to cry but instead they start pushing and shoving and it is time for me to retreat.

The talk about abortion has unsettled me. It is a long time since I was a young woman, and things have changed. There is access to contraception, and there is a general acceptance that a woman has the right to do what she wants with her body. There is no shame attached to having a child outside of marriage, and there is government assistance available for single parents. If I were a young woman now, I would have the advantage of looking at my options and be able to make an informed decision. In 1964, when I was 17, in a small town in England, I was so far from being able to make an informed decision that I did not tell my parents until I was seven months pregnant.

2. 1964

“Mum. I have to tell you something.”

We are on a tea break at the cleaning job we share at the Parker Pen factory in Dover where my dad works. It is only two hours each weeknight. We clean the offices and the ladies’ toilets and a man sweeps the factory floor and cleans the men’s toilets. The whole cold building next to the ferry terminal smells of ink. There is really no need for a tea break but she does not get much time to sit and relax at home. I am so afraid to tell her but it has to be tonight.

“I’m pregnant.”

The look she gives me is designed to shrivel. She has only ever had to look at me sideways to punish me. The look contains all the elements of what she is feeling—fury, disgust, and disappointment. I am the good child, the one she has never had to worry about. I am the child who will get a good job when I leave school, who will never have to work in a factory or a shop. She likes my boyfriend, Dixie, had trusted him too.

“Do Dixie’s parents know?” She is lighting a cigarette and her hands are shaking.

“He’s telling them tonight.”

“Well, one thing I can tell you for nothing, you’re not getting married.”

We wash up the tea cups and finish cleaning in silence. That is almost more frightening than her shouting at me and I wonder if she will ever speak to me again. I have seen her silent treatment in action and it never ends until she is ready. She will be thinking about my older sister, Cathy, who married at 16 because she was pregnant to a handsome and feckless Gypsy boy. That was five years ago, and she has recently been granted a divorce on the grounds of mental and physical cruelty.

When Mum does break the silence she says:

“I wanted more for you.”

Mum and I finish our work at the factory and get a taxi to Dixie’s house. He is in his room and his father is nowhere to be seen. I am grateful for that; he scares the living daylights out of me. He looks like James Mason but much sterner. After a career in the army he is used to being obeyed, and smartly. Dixie’s mother takes us into her bedroom and we talk about what to do. The room is full of disappointment.

The next day, Mum takes me to the family doctor for a check-up. He is cold and angry. “How could you do this to your mother?” However, he does not talk about contraception. He thinks that having made this big mistake, I will never agree to sex again until I am married. He is Marianne Faithfull’s uncle, but there is nothing rock and roll about him. There is no question of me keeping the baby and I will be sent to another town, to a home for unmarried mothers. Until a place becomes available I will stay with my sister who is living in Council housing with her two young children. She is at the other end of town, so I am unlikely to be seen by my mother’s neighbours. Not that there is much to see. I have not put on a lot of weight, and I have always favoured loose clothes.

A month later I have a place in an unmarried mothers’ home in Ashford, about forty miles away. It is the town where Dixie’s grandparents live, and he asks me to avoid the town centre in case I run into them. I accept that. I understand it. I am relieved that my own grandparents are dead or they might have died of shame. In their book, being unmarried and pregnant was a clear indication of sluttish behavior. Girls in my situation were “common as dirt”, common meaning low-class, badly raised, morally inferior, disgraceful. I do not know if his grandparents would think that about me, or whether they would be shocked to discover that their house had been the venue for our first successful attempt at sexual intercourse.

The night we first met, he had been sitting in the local coffee bar with Sue, a friend of mine from school who lived in the next town. The summer holidays were almost over and none of us wanted them to end. It had been a summer of swimming and tanning and smoking Gauloises with the French boys who inundated the town in the school holidays, taking menial jobs in the hotels and guesthouses. In the evening we would meet at Tony’s bar, which was ideal, because it was in a basement with low lighting and booth seating, which meant we had to squash up against each other. The darkness was the main attraction, though we told ourselves it was the Italian coffee machine. Jean Pierre had asked me out for coffee, but we had ended up in a group with his friends. When some of them left I waved to Sue, and they came to join us.

Dixie looked like a young James Dean, with grey blue eyes and brown hair swept back from his serious face. He was carrying a brown leather satchel and a camera, and looked like an explorer who had spent the day documenting the town and its inhabitants. He had, in a way, gathering material for his sketchbook. Dixie’s family had only recently moved to town, and he had just finished his first year at Canterbury College of Art. He was funny, despite his serious demeanour. Canterbury was not far away, but I found myself feeling disappointed that I would not see him around town. Later, as I waited for the bus, I watched him walking away—he was a bit on the short side, and his long stride looked awkward, as if he were trying to keep up with someone much taller. I did see him again. When the new school term started, I was able to say I had a boyfriend and to be surprised by the look on Sue’s face.

I had had boyfriends before him. There was a serious boy who was about to join the Merchant Navy and wanted me to wait for him, his best friend who convinced me not to wait, and Jean Pierre who let me help him with his English and pedantically corrected my French. They were short, sweet friendships that went no further than kissing. My mother assumed that I would learn from my sister’s mistakes, but just to be sure she would wait behind the front door at the time I was due back to be certain there were no lingering goodnights from whoever had walked me home. Her own mother had told her that kissing could make you pregnant, and if that was not true it was certainly where it all started. At 15, I knew a bit more about biology, even though I had skipped so many biology classes that the school report called me “unobtrusive”. I had made some sense of my mother’s instructions about where not to let boys touch me, and I was aware of the dangers of unprotected sex. However, all of that went by the board when I met Dixie. No-one had told me what passion felt like.

That Christmas was freezing cold, and the snow still lay deep on the ground days later. We were heading for Ashford to visit Dixie’s grandparents, but hitchhiking was slow because no-one wanted to be on the road in that weather. I had told my parents we were getting a lift so they would not worry about me. In the early hours of the morning, we reached the outskirts of the town and headed for the woods to wait for daylight. Dixie had lived in this town some years earlier and knew a hollow tree we could squeeze into for warmth while we waited for Poppy and Horace to wake up. The tree did offer shelter, but it was standing room only, and by the time we knocked on their door we were cold to the bone, our boots and socks sodden and icy. We drifted through that day in front of the fire, playing cards and drinking cherry brandy until it was time to go to bed.

Dixie had a plan. His bedroom was next to his grandparents’ room and mine was down a half landing with the bathroom in between. He was going to creep back down to my room once they were asleep. I lay awake, alert to the smallest sound, terrified and excited. When he came back along the landing I could hear his joints cracking and my own heart pounding. I wanted this. I wanted to lie naked with him, to have some feeling of being owned, possessed. I was afraid he would tire of me if we did not take this step. At the same time, I wanted his plan to fail. I was 16 and none of my friends had gone this far yet. Then he was there, standing naked in the light of the moon. Pale, shivering, smiling. He made the cold sheets colder for a while, but we were at last in a bed together instead of fumbling in dark alleys or at the end of the pier. The fumbling had been one sided up to now, so I was shocked by the size and hardness of his penis. I did not know what he expected me to do, so I did nothing except try to lose myself in the kissing moments.

The unmarried mothers’ home is not what I expect. It would have been a very comfortable country house in its day, but the town has crept closer and eaten up the surrounding gardens and orchards. What remains is the house, the stables, and a large area of lawn surrounded by mature trees. There are two large bedrooms shared by the ten girls in residence, a nursery, and the Matron’s private quarters. Downstairs, the impressive entry leads into a large sitting room with views onto the garden. The Matron’s office is here too, at the front of the house, so adopting parents can come and go without seeing any of the residents. Everything is clean and polished, and fresh flowers are always on the hall table. Though it is run by The Children’s Society, it is not institutional, except for the rules and regulations, and after a month I am used to the routines. Every minute of the day is regimented and revolves around the babies being fed at four hourly intervals. In between, the mothers clean and wash clothes, take the babies for walks, and rest themselves between two and four in the afternoon when the Matron takes charge of the nursery. The mothers-to-be are allowed out for walks in the afternoon but must be back by five, after which time no visitors are allowed. Dixie comes to visit me one afternoon, and I am so happy to see him, to see anyone who does not treat me like a prison inmate. The sun is shining, and we find a sheltered spot on the edge of a field. Either the al fresco sex or the fright of suddenly being surrounded by cows triggers my contractions, and later that night I am admitted to hospital.

“She’s from the Home.”

I’ve been placed on a trolley outside the delivery room and the nurses are checking my details. I am frightened and in pain, and the noises I hear around me are not reassuring. I am still feeling the shame of having my pubic hair shaved and being given an enema so that I don’t disgrace myself when I am pushing. I can hear a doctor encouraging some other poor woman to push. His voice seems unnecessarily loud. Everything is exaggerated here. Light and sound bounce off the white tiles, hurting my eyes and my ears. My feet are freezing but I don’t dare ask for a blanket. The matron has made no secret of what she thinks of “bad girls”.

In my own eyes I am not bad. I am stupid, unlucky, and naïve. Like all the girls in the Home. We do not deserve the treatment we get at the hands of the nurses and doctors who deliver our babies, who tell us it is our fault we are in pain and offer no relief, who cut us and stitch us up clumsily with catgut and without an anaesthetic, who clean us up without kindness. Care and compassion is reserved for married women only, although even they have to obey the rules of confinement. Our babies are brought to us only for feeding, then taken back to the nursery. For some mothers this is a rest break, ten days in bed with someone else looking after their other children. It is ten days when they can sleep through the night, because if the newborns wake up the nurses will take care of them. For the ten days I am in hospital, I have no visitors. I am in a public ward, and curtains are pulled around my bed during visiting hours, though I doubt it is to spare my feelings. The only kindness shown to me comes from a woman in the next bed. She is twice my age, is having her first child, and her husband is overseas. He finally makes it back to England one afternoon, to the hospital, to the ward, to her bed. The nurses give them the key to the storeroom so they can be together and have some privacy. I am happy for them, sorry for myself, and angry towards the nurses who have shown me no kindness. Furthermore, I am jealous. I have just given birth to my first child too, but nobody is celebrating.

Back at the Home, my mother comes with some baby clothes she has picked up in a church jumble sale. She is a constant and very good knitter, but knitting new baby clothes would raise questions she does not want to answer. It is the final confirmation that this baby will not be coming home with me. Some part of me had thought my mother might change her mind when she saw her granddaughter, but she has avoided looking at my baby. She would see her own face mirrored there.

We are given six weeks with our babies, like mother cats and their kittens. We breastfeed them, change them, bathe them, watch them as they sleep. As well as our cleaning chores around the Home, we now wash nappies, first in a large sluice in the old stable block, then by boiling them up with Lux soap flakes, rinsing them and putting them through a large mangle to remove excess water. They must be hung on the line by 9.00 a.m. and removed from the line by 4.00 p.m., before the evening dew. I am perpetually exhausted and one afternoon I fall asleep in the garden and add sunstroke to my list of afflictions. I am too sick to continue breastfeeding, and my baby is transferred to the bottle. It is the first step in our separation and I feel it badly.

There are older girls here who scan the newspapers daily looking for live-in housekeeper jobs where they can take their baby. They are girls who have been thrown out of their homes by parents who cannot face the disgrace. It is heart breaking. We are not supposed to get attached to our babies, but it is impossible to deny our feelings. The six weeks we are allowed are the six weeks the law decides is necessary for thorough health checks and matched placements. We are not supposed to look when our babies are taken from the Home, but I want to see the people who are taking my daughter. From behind a lace curtain in an upstairs room I see them walking across the gravel towards their car. They seem old, as old as my parents, and they have a small boy with them. I know nothing about them except that they can give my baby a comfortable home. I can give her nothing, except her name. My best friends from school have been suggesting names—Lisa, Jane, Lily—but the names mean nothing to me. I can give her nothing but her name, and I have called her Sally. I have nothing to remember her by, except two photographs Dixie has taken of us on the steps of the Home. A stranger would see happiness.

I catch the train back home by myself. Canterbury is on the way so I call in to see Dixie. He is living there now, closer to Art School and further away from me. I need some kind words and comfort from the other point of this triangle. I need him to tell me that we will always be together, that he is sorry we lost our girl. Instead he says, “It might have been different if it had been a boy”.

I have missed the last term of the first year of my Business Studies course, but I can retake the exams after the summer holidays and catch up with coursework in the meantime. The only people in my family who know about the baby are my parents and my sister. Everyone else thinks I was ill. My mother treats me like an invalid but only for a short time. She is torn between punishment and compassion. She has five children and can imagine what it would have been like to lose one.

3. 1965

“Sally. Are you OK?”

I am shivering uncontrollably on the station platform, even though it is a warm spring evening. I do not know it yet, but I am in a state of shock. Serious, physical shock. I am in pain, but I still think it will be alright, that I will get on the train, go home and go to bed, and lose a lot of blood in the morning. Move on. I try to be brave but it is not working.

“I think we should call an ambulance”.

He does not want to hear this but he knows it is true. He is as frightened as I am. When the ambulance arrives, the two men who help me into the back are brisk, and they talk to me in very loud voices. I do not want them to know what is wrong with me. They might have daughters my age.

“What’s your name love?”

“How old are you?”

“Where does it hurt?”

I am not bleeding yet and I do not want them to think badly of me. I am in pain but I still think it will be OK, that I will get to the hospital and spend a night in bed there and lose a lot of blood in the morning. Move on. My mother need never know. It is a year since I let her down by having a baby, and this time I need to deal with it without her knowing. I have a Saturday job in a chemist shop, and I asked the older female assistant if she could help me get some quinine tablets, but she refused. Abortion is illegal and neither Dixie nor I would be able to pay for the procedure. So we decide to try a method he has heard about, which seems less frightening than facing my mother with the bad news. In his bed-sit next to the railway line, with trains rumbling by every 15 minutes, we collude in the loss of our second child.

“What’s your name, love?” The paramedic is shaking me.

“Her name’s Sally.”

“I need her to tell me herself. Come on, sweetie, what’s your name? Where does it hurt?”

I tell them I am 18, that I have pains in my stomach, but I do not tell them the cause. I do not tell them about the bowl of hot water used to dissolve the cake of Wright’s Coal Tar Soap, the plastic tube finally inserted into my cervix, the carbolic acid smell filling the room as the hot liquid fills my womb. I have to tell the doctor though. He is Indian. He is furious. I am 16 weeks pregnant. By 15 weeks, the foetus can kick, curl its fingers and toes, and squint its eyes. By 15 weeks genitals have developed so the foetus can be seen to be either a male or female child, and the kidneys are working. My kidneys are not working. We have succeeded in killing this child, but I may be joining it in heaven. If I die, Dixie will go to jail.

I am taken onto a ward, and the curtains are pulled around me. It is late now, so the other women on the ward are asleep, or resting. I am groaning with the pain, but the doctor tells me to be quiet, that I deserve the pain for what I have done. He tells me not to wake the other patients. It takes him more than an hour to remove, piece by piece, the contents of my womb. I drift into unconsciousness. The last thing I hear is the doctor saying, “There’s nothing more we can do for her”. There is no tunnel, but there is light and peace. Leaving would be so easy, but there is a dreadful pain in my right arm, just below the elbow. It will not go away. It is keeping me here.

“Sally! Sally!”

It is my mother, leaning into me, digging her sharp elbow into the soft part of my forearm. I have let her down again, but instead of disapproval I see pain. Instead of anger, I see love. She thinks I am dying, and she will not let me.

When I am well enough to leave the General Hospital, a doctor chases after me and catches hold of the ambulance door as it is closing.

“Haven’t you got anything to say to me”, he yells.

He is short of breath from running. I look at him blankly. I have no idea what he’s talking about.

“Aren’t you even going to thank me?”

“For what?”

I have seen only nurses all week, sitting by my bed letting me suck on ice cubes. I have been allowed no food or drink and although I am being released from this hospital, I am being sent to a Convalescent Hospital where I will be nursed until my body recovers. I have lost so much weight that even my hockey player’s legs are slender.

“For saving your life,” he spits at me. “I saved your life”.

I do not understand why he is so angry. “Thank you”, I say politely, and the door closes.

It will be many years before I understand what he did for me. By not officially admitting me to hospital that night, he was able to keep the abortion off the record, to admit me the next day with “nephritis”, to save us from prosecution. And he may have saved my life, but he did not stop me from dying. My mother did.

After many weeks in convalescence, I go home in a taxi, this time with my mother, who really does need to treat me like an invalid this summer. I have been away for so long she has rented out my ground floor room without my knowledge, and I am now installed in the bedroom next to my parents.

When I have recovered, I go to Dixie’s house for dinner. His mother tells me in the kitchen that he had been distraught when I went into hospital. She tells me that he was crying, but I can see she does not understand why. She thinks it was just because he was worried for me, but he was worried for himself as well. His family does not know what really happened, and I feel as if, once again, I have taken all the blame. He is about to move to London to study at the Royal College of Art. I have once again missed the last term of my course, but the Technical College has agreed to let me finish it in the autumn. So I adopt my mother’s approach of “least said, soonest mended”. I have no doubt that he loves me, and I am excited for him. For the three months we are apart, we write almost daily, and I keep his numbered letters in a wooden box under lock and key, where I also keep the two black and white photographs of my daughter. “Sally, I love you like krazee.” Same.

4. 2017

This is what I am thinking about in The Lass. I am standing at the back of the dance floor now, watching the craziness that goes hand in hand with mourning. I made so many mistakes growing up. I almost died as a result of one of those mistakes. I am angry with my younger self, angry that she did not have the strength to resist the only option being presented, to resist the assumption that her life would be ruined if she kept her child, to resist the idea that a single woman with a child would remain forever single and the child forever fatherless. I did not know at the time that there were examples in my own family to demonstrate the fallacy of the “forever fatherless” child. I know now that my grandmother gave birth to her first child when she was only 14, and he was brought up in her family, as her younger brother. My grandmother’s mother was pregnant with her fourth child before she married their father. My grandfather was born six years after his mother’s husband died, but no-one thought he should not be acknowledged as a brother to her three older children. I cannot know if it would have been better to keep my child, if it would have been worse, but it would have been different. I would have stayed in Dover. I would have stayed in England. But right then, all I wanted to do was follow Dixie.

London created a myth of sexual freedom in the sixties. Swinging London. It was not like that for everyone. We were free to wear short skirts, but that came with the likelihood of attracting the wrong kind of male gaze. It was a time of mixed messages. A man in the street could tell me what he would like to do with his tongue, but I could report him to the police and be confident that they would look out for him. Sexual harassment in the workplace was tolerated. My boss could get away with slipping suggestive phrases into his dictation and laughing at my embarrassment. He knew who was more valuable to the company. I could look back on those experiences, and my reactions, as an indication of my repression, but I prefer to think of it as innocence. Dixie and I were an island of innocence, an island of two. We did not smoke, we did not drink, we did not live together, we were monogamous. I wanted this to never end. I wanted him to promise never to leave me, but I would be the one to leave.

5. 1970

Dixie is doing well at the Royal College of Art and moves into a flat with a group of students in his year. He paints the single room white and builds a mezzanine sleeping platform at one end. We are now living within easy walking distance of each other in South Kensington. The weekends I stay in London, we walk for hours through the parks, look at art in the galleries, fill our heads with knowledge in the museums, and take in the history of a great city through its architecture. We lie in bed at night and talk about the kind of house we will live in, the kind of life we will have in the future. I cannot quite believe it. I feel as if I am in a holding pattern, waiting for him to decide what happens next. Perhaps when he finishes his course this summer. It is what I tell my mother when she asks me.

Over the last two years, I have moved several times and am now living with a married couple. The flat has all the right attributes—top floor, my own room, and cheap rent. Moving in with Dixie would cut my expenses, but he has not asked me to do so. Dixie is not the lease holder on the flat, but I wonder why I am not an option when a room becomes free? I am not the kind of girlfriend to ask that question. I am not the kind of girlfriend to ask any awkward questions.

We have been together for eight years now, since the day before my sixteenth birthday. Surely, one day soon, he will ask me to marry him, or even live with him. I wanted this to never end. I wanted him to promise never to leave me, but I would be the one to leave.

6. 1971

“Hallo Mum? It’s me.”

“What’s wrong?”

Phone calls and telegrams are for emergencies. She knows I am in Yorkshire for the long weekend.

“Nothing wrong. I just have something to tell you. I’ve met someone else and I’m going to marry him. And we’re moving to Australia.”

There is silence at the other end and I can tell it is too much to take in.

“Can I bring him home to meet you at the weekend?”

“Of course you can. What’s his name?”

“Ian, but everyone calls him Noddy. You’re going to love him.”

I had met Nod at a dinner party six weeks earlier. Dixie was working on some artwork that had to be finished by the next day, so I went alone. Something happened across the table, something inexplicable. Although I told Nod I was in a relationship and could not see him again, we met a few weeks later when a mutual friend gave us a lift to Yorkshire for the long weekend. That night, the Friday of the long weekend, Nod asked me to marry him. He was leaving for Australia within the next two months and wanted me to go with him.

I went to see Dixie on Tuesday morning before work. I could have left it till the evening, when I would have normally been seeing him, but I would not have made it through the day without confronting what had to be done. Although it was early, he was sitting at his drawing board. I told him with my arms around him, and even now I am not sure what would have happened if he had asked me to stay. He did not ask me. He said, “Does he know you’ve had a child?” As if that would have made a difference. As if I would not have told the man I was about to marry. As if it was still a shameful secret.

It took him three weeks to ask me to stay, but by then it was too late.

7. 1981

“The doctor will see you now.”

The waiting room is government grey and the Department of Health doctors work in a repurposed office building in the city. There are fibre board partitions and cheap veneered desks left behind by the previous tenants. Grey carpet tiles and bare windows. There is a definite air of Kafka. I already have the job at the Australia Council, but a medical examination is part of the Public Service contract. The doctor is rude and angry, and although his mood and manner can have nothing to do with me, it feels personal. The medical records form asks if I have ever been pregnant or had a termination. Yes. Yes. The questions feel like a judgement.

“You’ve got a bit of a belly on you.”

I am shocked at his hostility, but I need this certificate. I need the job. Our book distribution business has suffered after a fire razed our rented city warehouse to the ground. Nod is trying to keep it running in a smaller warehouse closer to home. One of us needs to be earning money. The doctor is used to dealing with people who need him to sign that they are fit to be employed by the Government. The power must be eating him up from the inside. I want to tell him that he has a belly too, but I contain myself.

“I’m pregnant.”

“Even so…”

For the first few years in Australia Nod and I had worked for other people, saved for trips, and relaxed into the Australian way of life. Whenever I visited my doctor for another prescription for the contraceptive pill, he told me I should stop taking it and have children. I did stop after five years, when we had set up our own business and were working from home, but it had begun to look as if I had left it too late. Though we had been trying for five years to conceive, it could not have happened at a worse time. I cannot really believe it is happening, that after all I am not being eternally punished for giving away my first child and murdering my second. It is 17 years since my daughter was adopted, and I feel as if I have been given a second chance.

I have done a good job of putting my past behind me, but something about being pregnant has released me from secrecy. At 35 I am less concerned about shame and scandal, about having had an illegitimate child, but I still tell only one friend. Marnie is pregnant at 40 with her first child, and we find ourselves crying at the smallest things. We are both afraid of being older mothers. Of not being good enough mothers.

8. 1993

Nod and I are watching a documentary about adopted children looking for their parents and birth mothers looking for their children. So many sad stories, so many rejections. There are children who do not want to know their birth mothers, who feel that finding them is being disloyal to the families who raised them. There are birth mothers who have never told anyone they had a child out of wedlock and are afraid their lives will be ruined if the secret is disclosed. There is still so much shame. There are stories of failed reunions, of vicious treatment at the hands of the Catholic Church. The British Government has set up a contact register, not so that parents can find their children, but so that children can find their parents. I begin to feel not only that I was blessed to have been born into a Protestant family, but that it may be possible that my daughter would want to find me. I would want to know about my birth mother if I had been adopted. Nod is supportive when I tell him I would like to put my name on the register, but we decide not to tell our 11 year old son Julian until my daughter gets in touch. It could be a long wait. I will tell Dixie when I go back to England. I would not try to find her without telling him. I know how much that hurts. He had sought legal advice on finding her two years after I left, without telling me, without considering my feelings. I had relinquished all rights to contact when I signed the adoption papers, and in my eyes he had relinquished any rights when he asked me if I was sure the baby was his.

Back at my mother’s house a few months later, I am steeling myself to call him. The phone is outside the basement living room and I close the door behind me. With the door closed, it is dark in this cramped space between the stairs and the kitchen. There is a stool I can sit on, my back to the dumb waiter, which in Victorian times would have taken hot food from the kitchen in the basement to the dining room on the next floor and clean sheets and towels to the floors above. These days it carries whatever my mother needs to take to bed with her—her book, her glasses, and a glass of water. It is a long way up. I switch on a light so I can see my address book. Even with the light on, it not a comfortable space, surrounded by spare coats and dark, polished wood.

“Hi Dixie. It’s Sally.”

I could have just said hallo. We know each other’s voices so well. We chat for a while, and I am working up to telling him my plan for finding our daughter, but I am finding it difficult to bring up the subject. Thirty years after the adoption, there is a big bridge to build and even all these years later I still feel the stigma attached to having been an unmarried mother in 1964. We have caught up now, and there is a pause in the conversation. I am just about to bring up the contact register when he says: “Sally, do you realise we have a 30-year-old daughter?” I could hit him with a brick.

When I go back into the living room, my mother is reading. She looks up, and she knows something has happened.

“Are you OK?”

“Mum, I’m going to find my daughter.”

I say it quickly and it comes out a little coldly, as if I’m expecting her to disagree. It is painful to see your mother cry. I do not realise immediately that she is happy for me, that she wants me to find my child.

“Your dad and I often talked about her, wondered what had happened to her.”

“You never talked to me about it.” I am crying now.

“We thought it was better to let you forget.”

I tell her about the contact register, that usually the children will be searching for mothers. The father’s name does not appear on the birth certificate of an illegitimate child.

“So how does Dixie feel about it?” she asks me. She is ready to be defensive on my behalf.

“He wanted to hire a private detective, but I convinced him to try the register first. I’ll send him the forms and he can go from there.” I smile when I tell her this, so she does not worry about the thought of a private detective. “We agreed to give it six months before we start thinking about what we could do next.”

Later, my mother and I will both lie awake, remembering, recriminating, understanding, and forgiving. She will relive the guilt she felt when she insisted on the adoption, but maybe that will be tempered with a feeling that she did the right thing. Even if my parents had been able to bear the shame and the cost of raising another child, I see now that they had wanted a different life for me.

It is not as if I was alone back then. The contraceptive pill had not become available yet, and more than one girl from my school had to leave mysteriously. We were more worried about venereal disease than pregnancy. The burning question for us was whether syphilis or gonorrhea could be contracted from a public toilet seat. We knew how girls got pregnant but it did not seem to be the worst outcome from sex. We had seen the pictures.

Six months later, my daughter adds her name to the contact register and finds both her birth parents, but because I am in Australia, Dixie is the first to hear. He calls me because he has received a postcard from Sally with a return address care of a Post Adoption Agency. It is a standard procedure, and neither of us thinks for a moment that it is her real name. It is what I called her. It is my name and the only thing I could give her at the time. I will have to wait another week before my postcard arrives, a week in which things move very quickly. Instead of following standard procedure, Dixie calls the Agency and somehow talks them into giving him contact details for Sally. It is heavy handed, it is against the rules, and for a moment I wish I had done this alone. I had assumed I would be the first one she contacted, the first one she met, and I have to acknowledge I am jealous. However, he does tell me everything. When he tells me that he had only just sent in his registration, the same week Sally added her name, I express my amazement at the coincidence but not my irritation that he had taken six months to fill in the forms.

He says: “I spoke to her today. Her name really is Sally. She wants to contact you but she asked me to tell you a couple of things first. If you can’t handle them, then she doesn’t want to go any further.”.

I feel sidelined by the fact that he knows more about her than I do. If these two things could preclude a relationship with me, would she still foster a relationship with him?

“Ok, what’s the first?”

“She’s a lesbian.”

“Not a problem”, I say. I had been steeling myself to hear that she was a heroin addict. Maybe that is the second thing.

“The other thing is that she’s a Socialist.”

“I hope you told her that wouldn’t worry me? You always used to say I was a Socialist”.

“I said you were a Bolshie—not quite the same thing.”

We’re laughing, but he is putting me in my place.

“What about her family? Was she happy growing up? Do they know she has found us?”

“I’m not sure. I know her mother died when she was 12 and her father gave her the adoption papers when she was 16. Oh, and she’s got Oehlers Danloss Syndrome, which she must have inherited from you because it’s not in my family”.

I am taken aback by this. He has had enough time to find out what this Syndrome is, something I have never heard of, and to place the blame on my shoulders.

I have read the literature on the possible outcomes of a post adoption reunion and about the protocol surrounding first contact with an adopted child. Now I feel as if I need to talk to a professional or join a support group. The professional is not very encouraging. She tells me that children who lose their adopted mothers at an early age are carrying a lot of baggage, that there can be mental problems that may not surface immediately, that this child may have unrealistic expectations surrounding contact with her birth mother. The support group is so far out of my comfort zone that I only attend one session. All the women in this group have had very bad experiences, mostly involving rejection by their newly found children. Some of them are carrying the extra load of having been adopted themselves. Some have been rejected by their birth mothers, as if they were still a sin to remain unacknowledged.

By the time Sally calls me, I am afraid I will not measure up. She has been looking for me for eight years, but instead has found her handsome, charismatic, intelligent, creative, and, by now, famous father. I already have a picture of her in my head—she will be dark haired, intense, intellectual, resentful, and brooding—images designed to justify her forthcoming rejection of me. However, when she does call, she is charming, down to earth, funny, and a little overwhelmed by Dixie’s direct approach. She has my laugh, and I can see from the newly arrived photographs that she looks sometimes like me, sometimes like him. We talk about our first letters to each other, the difficulty of knowing what to say. She tells me that her friends advised her to write, “Dear Sally, Thank you for the big bum”. I think we will be OK.

I tell her about my family, that my mother knows I have been looking for her, but I ask her if she will meet me first, before she meets them. I want her feelings about me to come from meeting me in person and not be complicated by family stories or her reaction to other family members. She is keen to come out to Australia. She has been before. We may have passed each other in the street in Manly or Katoomba. I think at the time that it is unlikely, that I would have recognized her, but when I go to meet her at the airport, I approach several young women who could be her before we find each other. In person she looks more like her father than I had realised. We get 50% of our genes from our parents, but only 50%, so the features I do not recognize must come from earlier generations. She has my body shape and height. In fact, she is a little shorter than I am, and I find myself surprised by that.

We spend the day in Manly, where I used to live and where she has been before on a previous trip. She is well travelled, has seen parts of the world I will never see. We are both nervous and polite. We cannot fall into the easy casual conversation of strangers, because we are strangers with a shared history.

Sally has come to Australia for six weeks, and because I have to work, and we live in the country, she will spend some of that time with friends of mine in Sydney. Marnie and Max are good friends and easy to like. She can let off steam, have a break from our relentless questioning of each other, and have time and space to process our conversations. While she is with me, we both have the advantage of being in the company of my husband and our son, who is thrilled to have a sister. At 12, he is old enough to understand the story of Sally’s adoption and smart enough to ask me if there are any other children he should know about.

My daughter brings me photographs of herself as a child, photographs of her adoptive family. I see the people who walked away with her that day. I see the happiness in their lives. The camera captures only one aspect of our faces at a time, so Sally looks at times shy, at times determined, at times amused by the world. I look at two photographs of her aged around 11, and I think they look familiar. An old gypsy woman at Scarborough Fair once told me that I had seen my daughter, and now I wonder if she was right. However, it takes me only minutes to realise that Sally looks like Dixie’s younger sister at that age. Most importantly, Sally brings me copies of the adoption papers. It is strange to see my teenage self through the eyes of a social worker:

“Sarah (the name on my birth certificate and only ever used in formal situations) has decided that it is best for the baby to be adopted, and she hopes that her little daughter will soon be happily settled in a home of her own where she will have the love and care of both a mother and a father. Sarah’s father died when she was a young baby—he was a Petty Officer in the Navy and was killed in 1946 when mine-sweeping. Sarah’s mother has remarried and she is not willing to accept baby Sally into the family. The family is a healthy one.”

It is infuriating to see Dixie through the eyes of the same social worker:

“The baby’s father is 19 years old and he is an Art Student at College. He has been concerned for Sarah and the baby, but is not in a position to offer marriage. His interests are painting, drawing, music, swimming and walking. His father was formerly a Warrant Officer in the Army and now has a share in a family business. His mother is a house-wife. He has two sisters aged 8 and 12, and a brother aged 17. The family is a normal healthy one.”

For some reason, the use of capitals for Art Student infuriates me, as does the listing of his interests. Apparently I had none. My family is “healthy” but his is “normal and healthy”. His family members are correctly itemized. Mine are not.

“There is one sister who is divorced and has two children, and one brother.”

Why mention my sister’s divorce and offspring? Actually, I have three brothers. I want to shout this down the years.

“…it seems likely that the friendship will come to an end”.

I find enormous satisfaction in the fact that the friendship with Dixie has not come to an end. It is only a reaction, though, to the officious tone of Miss Mitchell at The Children’s Society office.

Sally tells me about her adopted family, the loss of her mother, the difficulties of being treated as an outsider by her stepmother, even before the revelation of her lesbianism. She tells me that her brother is angry that she has found me, that he sees it as disloyalty to their adopted family. He would never want to find a mother who had given him up. Everything she tells me is delivered in a careful way, filtered through her professional voice. She is a social worker and has studied psychology after several years as a nurse. She wants me to understand that she is not angry, and I feel that she means it. She tells me about her search for me and how she painstakingly examined records to find out whether I had married or whether I had other children. She had found a record of my marriage, but she had no way of knowing I had left the country. If she had only gone to the address on her birth certificate she would have found my mother.

She has met Dixie several times by now and tells me she is a little overwhelmed by him, by his lack of sensitivity. He has offered to pay for her teeth to be whitened, an offer she has no intention of accepting. She did, however, accept his offer to pay for this trip. Part of me is grateful for his generosity; part of me thinks it is the least he could do.

It is a strange time for us both. We are fascinated by our similarities and eager to absorb details of our differences. One day, sitting in the sun on the back deck, she tells me she hates her feet. When I look closely I can see her feet are the same as mine, and I cannot see what there is to hate about them. Our hands are the same, except she is left handed like her father. We both put our left hands to our necks when talking and driving. I would like to spend time just looking at her. The only chance I get to do that is when she falls asleep in front of the television and I can let my gaze linger on her fine skin and the hints of my mother in her nose and lips.

By the time she leaves, we have the beginnings of a relationship, but she is more relaxed with my husband and son, more at ease with my friends, than she is with me. I cannot assume that she will accept me, although I am desperate for it, but I cannot let her go without some physical contact. I ask for permission to hug her goodbye and she assents, but she is stiff as a board, and I feel as if I have overstepped the mark.

9. 1995

A year after Sally’s visit to Australia I went back to England to visit my mother. I was looking forward to seeing Dixie too. I wanted us to be able to talk about what had happened in the past, to feel released from the secrecy and shame. I stayed with Sally and her partner, Kate, for a few days, and he came to visit us there. Most likely I had invested too much in the anticipated meeting. There should have been something about that in the literature, but there was surprisingly little about birth fathers. Perhaps it would have been better to meet him alone, so we could talk freely. Sally had met him often enough for her to suggest to me that he had mild Asperger’s Syndrome, a conclusion that had startled me at first, but then had explained a lot about him. We had a lovely afternoon and evening together, but there was no acknowledgement of our previous relationship, our connection to this young woman, or the hurt that may have been held under the surface. We went to a fireworks display that evening and, under cover of the darkness and the smoke, I could no longer hold back the tears. As everyone around me oohed and aahed, their eyes to the skies, I tried to get my throat to unblock. All that hurt. All the words I wanted to say, but could not, because it would seem that I was blaming him. I had to make room for the fact that he was also a victim in the drama. He had lost children too.

Sally and I were becoming closer. She had taken up some of my hobbies, tai chi and drumming, and she always introduced me as her mother. There could have been no doubt. We shared so many characteristics it was slightly alarming—facial expressions, hand gestures, and the laugh. Our growing bond prompted Dixie to tell me he was afraid she would want to move to Australia. He asked me if I felt like her mother, if I had maternal feelings towards her. I said yes, but that was shorthand for all the emotions I could not express. He had no idea what it had meant to me to lose that baby, no idea how the memory of her had never left me. Of course I had maternal feelings, and they had been denied for 30 years.

I had been looking, without success, for the photographs I had of Sally as a baby so that she had some physical evidence of her first six weeks of life. I asked Dixie if he remembered those photographs and he told me he had them, that they were in the wooden box I had left with him for safe keeping. It was a box of treasures from our time together, letters, cards, and photographs. Treasures I wanted to keep but did not want to take with me into my marriage. He had burnt everything except the two photographs of Sally, and he offered to make copies for me.

10. 2002

If I had ever imagined I would be the mother of the bride, the picture would not have included two brides. I am sure my mother would never have imagined this either, yet here we are. Dixie, me, and our mothers, guests at the commitment ceremony of Sally and Rachel. I have not met Rachel’s mother yet, but I have heard she can be difficult. I feel a little surprised that she has not come to introduce herself. I am not hard to spot in a peach silk, embroidered Punjabi outfit. It is not until the end of the ceremony, when the mothers are asked to come up and light a candle, that I see her. I smile but she does not respond. I put this down to extreme shyness, and when the ceremony is over, I find her to introduce myself.

“Hallo. I’m Sally’s mother.”

“Her mother? Didn’t you give her away when she was a baby?”

She is contemptuous, not shy at all. I am so amazed by her response that I laugh out loud. Then I go to find my own loving, open, broad-minded mother, who has embraced the idea of a lesbian wedding wholeheartedly.

“What a wonderful day”, she says. “So many lovely girls.”

11. 2006

It was cool on the riverbank. We had taken our drinks over to the waterfront opposite the Tea Gardens Hotel. My new neighbour, Margaret, and I had spent the week at a course for beginning writers. It had been a liberating experience for me in an unexpected way. I had begun the week writing amusing stories about my family, because I find them endlessly funny and loveable, but the other women at the workshop were writing about the pain of their lives, the trauma of childhood events beyond their control. Every day there were tears around the table. I did not want to write about the sadness in my life. I was still recovering from the death of my husband, still devastated by the fact that I would have to sell the house that we had built because I could no longer maintain the mortgage. Furthermore, I did not have the courage of those other women, the courage to share pain and anger.

I told Margaret the story of my daughter, the joy of finding her and becoming part of her life, the sadness of being so far away from her. On the riverbank that night, I told Margaret about my suppressed fury at Dixie, his insensitivity or deliberate withholding of the photographs of Sally. I had been waiting for them for nine years. She said I should write to Dixie, tell him exactly what those photographs meant to me, and how healing it would be for me to see them. I agreed to write the following week, after my 60th birthday. I was too busy organising what would be the last birthday party in my house.

A week later, the house was packed with people in fancy dress. The dress code was op-shop formal, but a pirate or two had turned up. My son Julian and his friends had set up a corner with a drum kit and guitars. All my old friends were there, except Max and Marnie who were on the way from the Blue Mountains, a five hour drive. When they did arrive, Marnie turned me so that I was facing away from the door, so that I could not see their present. I imagined a large bunch of flowers, but when she let me look I saw my daughter standing there. There was a fraction of a second while I took this in, while my brain caught up with my eyes and everyone else held their breath. Then I took Sally into my arms. I was not the only one crying.

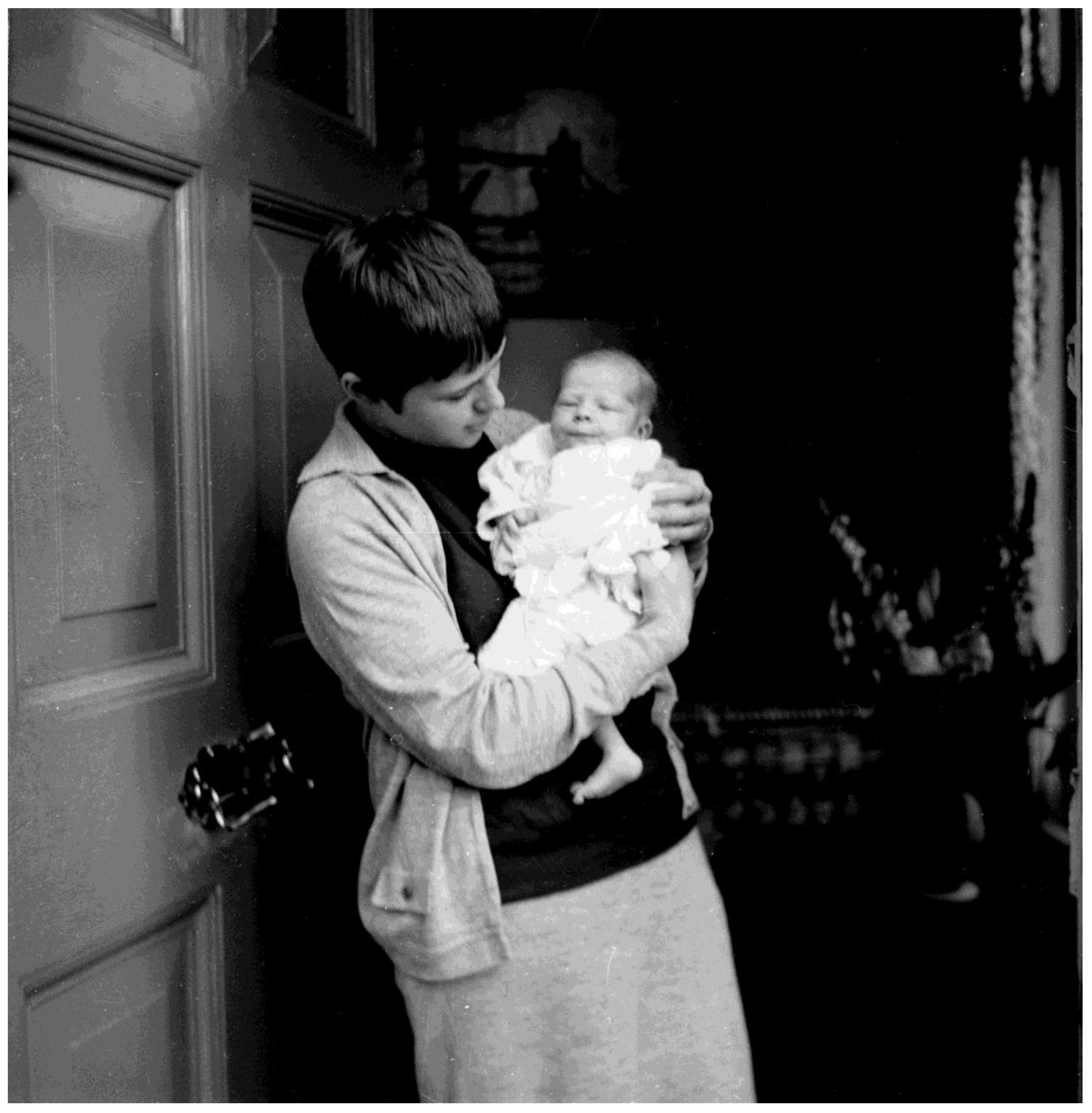

Sally was the best birthday present, but she also brought me a present from Dixie. A photograph of a young woman in front of a door that opens onto a welcoming hallway. There is a dark polished table and fresh flowers behind a young mother holding her child tenderly for the camera. See

Figure 1.