Abstract

This paper describes and analyses a particular safety practice, the written pre-task risk assessment, commonly referred to as a “Take 5”. The paper draws on data from a trial at a major infrastructure construction project. We conducted interviews and field observations during alternating periods of enforced Take 5 usage, optional Take 5 usage, and banned Take 5 usage. These data, along with evidence from other field studies, were analysed using the method of Functional Interrogation. We found no evidence to support any of the purported mechanisms by which Take 5 might be effective in reducing the risk of workplace accidents. Take 5 does not improve the planning of work, enhance worker heedfulness while conducting work, educate workers about hazards, or assist with organisational awareness and management of hazards. Whilst some workers believe that Take 5 may sometimes be effective, this belief is subject to the “Not for Me” effect, where Take 5 is always believed to be helpful for someone else, at some other time. The adoption and use of Take 5 is most likely to be an adaptive response by individuals and organisations to existing structural pressures. Take 5 provides a social defence, creating an auditable trail of safety work that may reduce anxiety in the present, and deflect blame in the future. Take 5 also serves a signalling function, allowing workers and companies to appear diligent about safety.

1. Introduction

Written pre-task risk assessments are a widely used administrative safety practice. The practice is commonly referred to as “Take 5 for safety” [1], and throughout this paper the generic name “Take 5” will be used. However, Take 5 exists under many names and variations. Later in this paper, we provide an indicative (but by no means complete) list of more than thirty alternate names for Take 5, along with industries in which each term is known to be used. Whilst the proliferation of names and variations gives some indication of how widespread Take 5 is as an industrial practice, the academic literature is almost silent about how Take 5 is performed, what it is intended to achieve, and whether it is effective. To the extent Take 5 is mentioned at all, it is usually as a passing reference as part of a package of behavioural measures for safety (see e.g., [2,3]).

A typical Take 5 is intended to be performed as follows. At the start of the shift, when recommencing work after a break, or when starting a new task, an individual or representative of a small team will commence the Take 5. The worker will consult a form, card, or mobile phone app that provides a series of yes/no checklist items. The initial items refer to generic safety precautions, such as whether workers have been inducted, understand the work, and have the correct equipment to perform the work safely. Further prompts ask the user to identify hazards and to confirm that appropriate controls are in place for any identified hazards. The form is signed and is physically or electronically returned to a safety representative.

The essential features that distinguish Take 5 from other safety activities are:

- the activity is performed by either the person performing the work or a member of their immediate team;

- the activity is performed at the site of the work, immediately prior to the work being performed;

- the activity includes the completion of a paper or electronic form, including multiple checklist items; and

- the same process and documentation are used for a variety of activities.

Take 5 sometimes includes the following additional features:

- assessment of the risk of each hazard, using a risk matrix;

- “Traffic Light” coding or imagery (red for “stop”, amber for “proceed with caution”, green for “go”);

- open questions, requiring the user to describe hazards and controls;

- individual or collective incentives for completing the Take 5 form, such as placing all completed forms in a box and conducting a raffle-style draw for prizes;

- recording of data from completed Take 5 forms to keep track of the frequency of workplace hazards and controls; and

- consultation of Take 5 reports during accident and incident investigations, as evidence about whether workers were generally paying due regard to safety or whether they were aware of specific hazards.

Take 5 bears some similarity to checklists [4], with the key difference that checklists are specific to a particular task or situation; to work permits, with the key difference that work permits are prepared in advance and used to authorise or coordinate work by someone other than the worker [5]; and to safe work method statements [6], with the key difference that safe work method statements often cover multiple instances of a work activity and thus are not completed by every person or team conducting that activity.

Whilst many safety practitioners believe that Take 5 is an effective and cost-effective safety practice [7], there is also a large volume of openly cynical commentary about both the intent and the efficacy of Take 5 [4].

In this paper, our primary question is “Does Take 5 improve safety?” Having answered that question emphatically in the negative, we also explore why Take 5 continues to be used by many organisations.

We make an evidence-based argument that Take 5 is a form of “safety clutter” [8]—work performed in the name of safety, which does not provide safety benefit. Safety clutter accumulates and persists because of workplace structural and social pressures rather than well-reasoned decisions about how best to improve safety. Specifically, we suggest that Take 5 is a type of “social defence”—an organisational ritual that has the primary function of containing anxiety [9]. We also suggest that Take 5 plays a role in allowing individuals and organisations to display their carefulness and diligence in safety matters.

The central evidence for our argument comes from an alternating treatment trial on an infrastructure construction project, involving periods of intensive Take 5 enforcement, optional Take 5 use, and banning of Take 5. During each phase of the trial, we observed both the use of Take 5 and the work safety behaviours intended to be influenced by Take 5. Further evidence to support our argument comes from qualitative ethnographic observations on a variety of infrastructure, mining, energy, and construction work sites in Australia.

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we provide an overview of the history of Take 5, and the rationales for its use. Since Take 5 is not well documented in the academic literature, this section attempts to reconstruct a plausible theoretical case for Take 5 efficacy. In other words, if we assumed that Take 5 worked to improve safety, how and why would it work? In Section 3, we provide the details of our data collection, including both the field experiment design and the ethnographic discovery activities. In Section 4, we present the results of our analysis. This analysis follows the method of Functional Interrogation introduced by Havinga [10], in which we consider each of the plausible functions of Take 5 and examine the evidence that Take 5 successfully fulfils each function.

After presenting our conclusion that Take 5 does not fulfil any of these functions, we provide further analysis and discussion to explain why Take 5 continues to be used as a workplace tool despite its lack of efficacy. We also consider the extent to which our findings are likely to be specific to this particular study and argue that our findings are inherent to the Take 5 activity itself, not just one particular implementation of the practice.

2. Where, When, and Why Was Take 5 Invented?

2.1. Origin Story

There is no definitive time or place where Take 5 in its modern format was invented. Whilst some recent papers (see e.g., [4]) make statements about the “proper” purpose of Take 5, such claims are made without reference to historical evidence. In this section, we piece together how we believe Take 5 came about, acknowledging that the scarcity of evidence adds a high degree of uncertainty to this account. Several early ideas that precede the Take 5 concept include the “Five Point Safety System”, “Employee Safety Cards”, and “Take Time to be Safe”. These ideas produced and encouraged proto-Take 5 activities and products that were widespread by the late 1980s. Around that time, a particular type of behaviour-based safety became popular, with a heavy emphasis on written observations of safe behaviours. Probably at multiple times and places, the proto-Take 5 transformed into its modern format.

2.1.1. The Five Point Safety System

The Five Point Safety System began in the underground mining sector in Quebec, Canada, and it is usually credited to safety engineer Neil George [11]. It is variously known as the “Five Point Safety System”, “Neil George Safety System”, and “Quebec Safety System”. These names have been retained as the system has been copied, adapted, and evolved, such that current practices share these names, but there is little other resemblance to the original practices.

Neil George worked at underground mines for Inco in Ontario, Canada, from 1936 until 1947. Contemporary descriptions of safety practices at Inco (see e.g., [12]) describe a heavy emphasis on safety promotion, spreading the “safety gospel” through stunts, meetings, and personal messaging via managers and supervisors.

From 1948, George was Director of Safety at Western Quebec Mines Accident Prevention Association, later Quebec Metal Mines Accident Prevention Association. The earliest description of his system comes from a 1968 visit to Quebec on behalf of mining operations at Broken Hill in Australia [13]. The “five points” were

- Check the entrance to work places.

- Check that the working place and equipment are in good order.

- Check that the job is being worked safely.

- Discuss a topic of safety.

- Do the men know how to continue to work safely?

These were instructions to supervisors, not directly to workers. The supervisors would carry “Safety Cards” listing the five points, with spaces to document any identified deficiencies, any remedial actions, and the safety topic discussed. A Safety Card would be completed by the supervisor and left with each pair of workers. When higher level managers visited the mine, they would inspect and sign the cards.

From Sellar’s explanation [13], it is clear that the Five Point Safety System was targeted at the “minds of men”—i.e., the prevention of “unsafe acts” through building increased conscientiousness and awareness of safety. Although the five points include reference to physical workplace factors such as the environment and tools, this was a means to an end, drawing explicitly on the Hygiene-Motivation theory of Herzberg et al. [14] to use management interest in safe working conditions as a driver for worker motivation to act safely.

Variations of the Five Point Safety System were adopted in underground mining throughout Canada, as well as in South Africa and Australia.

2.1.2. Safety Cards

“Employee Safety Cards” were in use as early as 1931 [15]. These cards were part of a package of educational measures including bulletin boards, night classes, and meetings. The cards were changed monthly, with each containing a new set of reminders about specific hazards. Specific purpose safety cards have been used in various ways, such as passenger safety cards in aircraft, hazardous chemical safety cards, and civil defence evacuation cards. More generic safety cards were (and still are) available as commercial products, typically plastic or laminated, with lists of hazards or safety precautions.

Safety cards were primarily intended as educational tools. The card format allowed the worker to carry and read the information at convenient times, and workers were even permitted and encouraged to take the card home after work [15]. The information was detailed and often referred to very specific hazards—providing information rather than exhorting the workers to behave safely.

Some variants of safety cards were clearly intended as checklists to be used directly in hazard spotting, rather than as educational tools. The card was positioned near the location of a hazardous activity, such as entry into a confined space, and the worker was supposed to consult the card before undertaking the activity.

2.1.3. Take Time to Be Safe

Slogans such as “Take Time to Be Safe”, “Take Five [minutes or seconds] for safety”, “Take 10 s to be sure”, and “Stop and think before you act” appeared throughout the twentieth century. The time taken sometimes refers to an activity such as attending a training session or meeting with a new worker, but more often it refers to taking time before a potentially hazardous task. As a typical example, the 1961 article “Take time to be safe” is a general exhortation to workers to check for hazards before they undertake a dangerous task [16].

Unlike the Five Point Safety System, which was focussed on worker motivation, Take Time to Be Safe appears to have been more about identifying and mitigating unsafe conditions before beginning the task. Alliman [16], for example, refers to taking ten seconds to make a “visual safety check”, comparing this favourably to losing forty years of life.

The “Robens Report” into workplace safety in the United Kingdom in 1972 made specific mention of the role of workers in hazard spotting [17]. The report notes that whilst the most prevalent practices for worker involvement were through unions, safety representatives, or joint safety committees, some firms were adopting universal engagement policies where every worker was involved in safety activities.

There was a gradual growth of supporting documentation, such as training material and laminated reminder cards. These co-existed with other safety documents. A team leader or site supervisor might carry a binder containing completed permits and instructions for high-risk work, blank forms for requesting permits or conducting risk assessments, forms for the recording and reporting of hazards and incidents, and reminder materials.

2.1.4. The New Behaviour-Based Safety

The 1980s and early 1990s saw the widespread adoption of “behavioural science” and “behaviour-based” safety programs. The use of behavioural science to understand and influence safety practice was not a new phenomenon, but the particular programs that became popular at this time carried a previously absent emphasis on documented observations. They relied not just on psychological encouragement of safe behaviours but on data collection and analysis to refine the methods of encouragement [18]. Managers, supervisors, peer-workers, and ultimately the workers themselves were trained to observe work performance and record compliances and non-compliances with safety rules.

It is probable that the Take 5 practice appeared near-simultaneously in multiple places at multiple times, as the existing practices, already starting to suffer from an accumulation of documents and forms, collided with the new focus on creating auditable traces of work. Whereas, previously, companies might have encouraged taking time to think about risks or even created signage and other reminder tools (even laminated “Take 5” cards), the new doctrine required written cards or forms to check that the activity had taken place. There was simultaneous pressure to record every aspect of safety and to reduce the number of different types of safety documents. The Take 5 pad was created—integrating reminders, conversation prompts, risk assessment, and hazard recording into a single product.

Safety promotion tends to generate brand names, acronyms, and symbols that spread faster and last longer than the activities they refer to, so it is uncertain when and where each variant of Take 5 became a written rather than an informal activity, and whether each acronym is based on a theoretical model of behaviour or is merely a convenient selection of words to spell the acronym. Table 1 provides a list of various versions of Take 5.

Table 1.

Alternative names for Take 5.

It is reasonable to dismiss names such as “Stop Assess Fix Evaluate” (SAFE) and “Stanna upp, Tänk efter, Agera, Reflektera & Kommunicera” (STARK—meaning “strong”) as contrived acronyms. However, “Stop Think Act Reflect” and “Stop Think Do”, along with the traffic light symbology, closely parallel clinical training programs already in use for dealing with classroom disruptions and troubled teenagers [19,20]. This could be a coincidence, but it is circumstantial evidence that Take 5 was not just documentation attached to an existing informal practice, but deliberately incorporated ideas and practices that were popular in behavioural psychology at the time. This also raises the intriguing possibility that Take 5 explicitly involves treating skilled workers as if they were misbehaving schoolchildren.

By the mid to late 1990s, Take 5 was a well-established practice under a variety of names, across multiple industries and countries. There were commercial training programs that encouraged the practice and industry-body documents giving details for how companies could embed Take 5 within their own safety programs. For example, a European Union report on Task Risk Assessment mentions that there existed commercial safety training programs for the petroleum industry that included informal risk assessments for low-risk tasks, conducted by the workers each time they perform those tasks, and that these risk assessments were sometimes written down [21]. Hudson and Smith [22] wrote a manual dedicated specifically to the implementation of a program of field-level risk assessments, with all of the essential features of a Take 5, as well as incentives for completion and analysis of data reported through the forms.

The multiple organisational needs that gave rise to Take 5 continued to encourage both simplification and complication of the documents. No document can simultaneously be a simple pocket reminder, a risk assessment process instruction, a comprehensive checklist, a hazard reporting system, and a behavioural observation record. Take 5 forms went through cycles of adding more and more detail onto the form, followed by attempts to streamline the process. Sometimes the streamlining would remove the need for written records altogether, until there was a demand for evidence that the process was being followed, or the Take 5 was re-integrated with a hazard reporting process in order to simplify the number of different forms.

2.2. Rationale

Drawing from the history, the limited academic work, and discussions with staff from a range of companies, we suggest the following rationales for the use of Take 5. Our intent is not to claim that Take 5 does work in these ways, or that these are the reasons that companies adopt Take 5, but to list plausible functions that Take 5 could perform. We then draw on the data from our study to examine whether these functions are in fact provided. Each function provides benefit at a different time, allowing the functions to be easily distinguished.

2.2.1. Planning the Safety of Work

The most immediate function a Take 5 might fulfill is to directly alter the plan for the task that is about to be completed. For this to happen, the Take 5 would need to be completed at a particular time—prior to a starting the task, but after local information about the conditions of the work is known. The process of completing the Take 5 would lead a person to actively look for hazards and to take those hazards into account in their planning of the task. An effective Take 5 would lead to more hazards being considered, or at least more explicitly and consciously acknowledged by the workers. This in turn would lead to either controls being put in place or work methods that are better adjusted to those hazards.

Under this view, Take 5 would have an immediate effect on improving safety by promoting safer work methods, including recognisable controls. The hazards recognised would need to be relevant to the task, and the controls would need to be effective against those hazards. What is written down, however, would not necessarily have to be exhaustive or accurately phrased. Accuracy of the record would be secondary to the appropriateness of the actual plan followed.

This rationale matches the original intent of “Take Time to be Safe”. The hypothesised advantage of Take 5 over previous practices would be that requiring the worker to complete the form would lead to more comprehensive or explicit consideration of the hazards, increasing the likelihood that the activity would improve the plan for the work.

2.2.2. Increasing Heedfulness

A less direct function leading to the same outcome would be for the Take 5 to influence the mindset of the worker so that they have an ongoing likelihood of identifying hazards, implementing controls, and following safe work practices.

Under this view, completing the Take 5 would create a short-term increase in heedfulness, causing the worker to continue to look for hazards and suitable controls for some period after the completion of the Take 5. Regular exercise of the practice would sustain the effect and might instil a general habit that people would also exercise even when they did not complete a Take 5 on a specific occasion.

The effect would be the same as for the planning function, using a slightly different mechanism. The increased heedfulness would improve safety by promoting safer work methods and would also make workers more sensitive to hazards that show themselves after the Take 5 was completed. The expectation is that operators would notice hazards that otherwise would go unnoticed and that are at least potentially relevant for the task at hand. This noticing of hazards, however, does not necessarily translate to what is written on the Take 5. What is written down does not have to be exhaustive or accurately phrased, as keeping an accurate record requires additional skills and efforts that are not the same as the mindset.

This function matches the general intent of the Five Point Safety System. Whilst modern safety science is rightly sceptical of the moral overtones attached to “increased conscientiousness” or “safety ethic”, the intended effect could be viewed more neutrally as an increased orientation towards risk in general, or towards specific sources of risk. The hypothesised advantage of a Take 5 would be that having the workers complete the task themselves, rather than as a conversation with a supervisor, would enhance the effectiveness. This is in direct contrast with the hygiene-motivation theory supporting the original Five Point Safety System.

2.2.3. Education

A more long-term function that a Take 5 might fulfil is as a broad educational tool, not specifically attached to the performance of any particular instance of work. For this function, completing a Take 5 would be a learning or learning-reinforcement exercise, increasing the person’s general knowledge about workplace hazards. There would be no particular need to complete the Take 5 at the beginning of a shift or task, but having set occasions for completing the Take 5 would encourage regular revision, in the same way that a classroom teacher might have a daily “pop quiz” to help students revise key concepts.

Under this view, Take 5 would have a long-term effect on improving safety, slowly raising the average worker’s knowledge and awareness of hazards and reducing unsafe behaviours caused by knowledge deficit. For this function to be plausible, the Take 5 card would need to contain informative content or have some other means of providing feedback to the worker. Otherwise, the card could reinforce a habit, but could not support learning.

This rationale matches the original intent of Employee Safety Cards. The hypothesised advantage of a Take 5 over a Safety Card would be that requiring the worker to write something on the card would increase the amount of learning, either by enforcing greater compliance or through the educational benefit of writing something down to help remember it [23].

2.2.4. Distributed Hazard Identification

Some people understand Take 5 to be more focussed on data collection than on influencing workers. For this function, it is the information recorded on the Take 5 that is important, rather than the act of writing. The benefit would come after the Take 5 forms have been collected and analysed. Individual items recorded on a form, or patterns of items across multiple forms, would give rise to management actions to improve working conditions. For example, a pattern of workers using less effective controls might cause management to investigate why more effective controls were not considered to be suitable.

Under this view, Take 5 would have a delayed effect on safety, not providing any immediate benefit to the shift or task for which the Take 5 was completed. The benefit would come on future occasions, after work conditions have been changed.

Unlike the other rationales, this hypothesised benefit requires the Take 5 to be completed accurately and comprehensively. The data must also be reviewed promptly and carefully. For example, a 2013 fatality report in Colorado criticises the mine management for using a “Five Point Card” system as their primary means of conducting and recording workplace hazard identification [24]. The report indicates that workplace inspection must be carried out by “competent persons” and that distributing the responsibility amongst all workers does not meet this requirement.

This function matches the general intent of hazard reporting forms. Organisations that use Take 5 may also have separate hazard reporting systems, but under this function, they view Take 5 as either a primary or supplemental mechanism for reporting hazards.

2.2.5. Demonstration of Due Diligence

Whilst the Take 5 is intended to be completed prior to work commencing, the written record persists throughout and beyond the shift or task. Another possible function for Take 5 is as evidence for whether the work was conducted safely. This might be non-specific, where the completion of the Take 5 indicates that the worker had a general concern for safety. Alternatively, the information on the Take 5 might also be considered as evidence that the worker knew about a particular hazard or that a particular control was or was not put in place.

Under this view, performance of the Take 5 would need to be a transitive function, in the sense that a worker providing evidence that they have due regard for safety would help the organisation show that it has met its obligations for safety.

It would not be consistent with this function for workers to use Take 5 records to protect themselves against criticism from the organisation, or for the organisation to use the presence or absence of Take 5 records to blame workers for incidents. To the extent that such motives or behaviours exist, they would undermine rather than support the due diligence function.

Demonstration of due diligence does not necessarily require that Take 5 is effective in improving safety, or even that individuals believe it is effective, provided that there is a social or administrative consensus that the Take 5 is an appropriate form of evidence that the workers, and transitively the organisation, have shown general concern for safety or have addressed specific hazards.

3. Method

3.1. Setting and Participants

The main study was conducted within an infrastructure construction project. The project was one of many ongoing projects within the same region, managed by an alliance of government and private industry. This alliance was also the main research partner in a multi-year research project investigating safety clutter. The research project included multiple smaller investigations, including this Take 5 study.

The alliance employed some operators directly, but most work was subcontracted to firms referred to as “delivery partners”. Workers from long-term delivery partners were included in the study. In total, there were approximately 80 workers across several delivery partners, with between 30 and 40 workers present each day on the construction site. Specialised one-off contractors or delivery drivers were not actively sought out during the study.

The alliance relied primarily on the safety management system of one of the private industry partners. This included a Take 5 booklet. Workers either carried this booklet or kept it in their vehicle. On the inside cover of the booklet, there were coloured boxes. Each box covered a separate topic, including critical risks, traffic management, manual handling, personal protective equipment (PPE), housekeeping, and environment. For each topic there were questions written in a small font. These questions were about the presence of hazards and controls in general terms (e.g., “Do I have appropriate PPE?”).

Each page within the booklet was a two-sided card, with spaces for recording information. The front started with spaces for recording the task, employee name, supervisor name, date, and employee initials. This was followed by 11 tick-box items. These items varied between references to other policies (such as complying with golden rules), presence of controls or safe conditions (such as whether there was safe access and egress), and finally whether the person felt safe to conduct the task. The instruction on the booklet said that if any of those questions were answered in the negative, then the issue should be resolved and/or addressed with the supervisor before proceeding to the back of the card. On the back of the card there was a table for listing hazards and controls. This table contained six empty rows for hazards and controls.

Throughout the organisation, there were different interpretations of the policy on how often Take 5 should be conducted. These interpretations included that Take 5 was an ad hoc activity to be conducted when needed; Take 5 was to be completed a minimum of once a day and also if there was significant unplanned variation to the work for the day; Take 5 was to be completed at the start of the day and after each break (i.e., typically three times a day); there was a fixed target of three cards per person per day.

At the site, about 100 Take 5 cards were handed in to management per month. However, strict interpretation of the policies would require more than 2000 cards be completed over the same period. This mismatch between expectations and actual practice created ongoing pressure to increase the use of Take 5. Take 5 was emphasised during the induction process, daily pre-start meetings, and toolbox talks. There was a monthly draw using the submitted Take 5 cards as tickets. The prizes from the draw included items such as lottery tickets or tools. There was also a monthly prize for “best” Take 5.

Most Take 5 cards would not be read or inspected by anyone other than the person who wrote it. There were three occasions where a safety manager or supervisor might read operators’ Take 5 cards. The first occasion would be during a supervisor or safety advisor’s walk around, where they could check what was being written on a Take 5 card and comment on it. This was a rare occurrence, and when it did occur, it would usually be for less experienced workers. The second occasion would be for the monthly prizes. The third occasion would be after an incident. Whether a Take 5 was completed and what was written on it was part of any investigation. Apart from these occasions, non-completion of Take 5 would usually go unnoticed.

3.2. Procedure

To improve ecological validity, the researchers did not directly attempt to control the behaviour around Take 5 use. Whilst managers, supervisors, and workers were aware that a trial was happening, the instructions at each phase were issued by site management.

The study was conducted in five phases, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Take 5 card study phases.

The first phase was a baseline of three months to develop a thorough understanding of how Take 5 cards were utilised. During this time, the researchers made no attempt to influence Take 5 practices. A researcher (the second author) visited the site three times per week, with each visit lasting between three hours and an entire workday. The baseline period also served to familiarise workers with the presence of the researcher, minimising participant reactivity for the remaining phases.

After the baseline, there were successive periods of “intensive use”, “optional use”, “no use”, and “optional use”. Transition between phases was agreed between the researchers and delivery partners, communicated to the workers by their supervisors, and reinforced by the site safety manager.

During “intensive use”, the delivery partners attempted to create optimal conditions for the cards to be effective. There was an interactive toolbox, supported by the researchers, to foster consensus around the purposes that Take 5 cards are intended to serve and to give workers a choice about the manner and frequency of the Take 5 activity. It was agreed that a minimum of three Take 5 cards should be filled in by the workers: one after pre-start, one before lunch, and one in the late afternoon. This collectively agreed-upon standard was to maximise buy-in from the workers. The standard was then enforced with reminders from the site managers and safety advisor as well as a site-wide incentive for full compliance. A reminder was given to everyone collectively at the morning toolbox talk and throughout the day to individuals and smaller groups.

During “optional use”, there were no prompts, reminders, or incentives. Workers were free to either use or not use Take 5 cards and were told that there would be no external incentives or consequences contingent on Take 5 use. The monthly draw was retained, but participation in the draw was not based on Take 5.

During “no use”, there was an agreement with all delivery partners that no Take 5 or equivalent would be used on site. Delivery partners were asked to ensure that workers remained eligible for any incentives that would otherwise apply.

The use of alternating phases on a single, multi-organisation site created an opportunity to observe the effect of varying levels of Take 5 use, whilst retaining as much ecological validity as possible. The conditions allowed us to observe multiple instances of the same workers conducting very similar work tasks and

- (1)

- supported by a mandated Take 5;

- (2)

- supported by a Take 5 that they voluntarily chose to undertake; or

- (3)

- not supported by a Take 5.

The length of the phases and the interweaving of “optional use” periods were designed to observe both the immediate and moderately sustained effects of Take 5. From the rationales discussed earlier, this allowed us to directly test every hypothesised function except education, which is presumed to operate over a longer period than our study.

3.3. Data Collection

During all phases, the study relied on a combination of measures to observe if, when, and how Take 5 was used and how the use of Take 5 influenced the conduct of work.

The number of Take 5 activities conducted was reported by site management to the research team. The data were collected on a daily basis and supplied to the research team after the conclusion of all five phases of the project. While the data listed Take 5 forms provided per person, it did not include how many or what tasks people engaged in each day. In addition, there was no reliable data for who was on site each day from each delivery partner. While there were no major changes in workforce observed during the trial, construction projects progress in a way that leads to non-random changes. As such, the data are not controlled enough to explore or test for very minor changes in Take 5 usage or outcomes.

An observational marker scheme was used to assess heedfulness. The marker scheme was based on Back, Furniss, Hildebrandt, and Blandford’s “Resilience Markers” approach [25]. A combination of pre-defined markers and newly observed markers of heedfulness were collected. The specification of the markers to the utility industry was based on earlier research with one of the research partners.

The heedfulness markers were thematically grouped into categories and subcategories. A category is a group of markers that all relate to the same subject or object. The categories pertained to heedfulness of (One-)Self, Others, Rules, Equipment, the Environment, and Time, as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Categories of heedfulness with examples.

Categories can be physical (e.g., equipment) or abstract (e.g., time). A subcategory is a subordinate descriptor of a category that characterises certain behaviour within a category. Examples are checking, adapting, or protecting the environment. For the heedfulness markers, the term “workers” is used to relate to the people who perform physical work onsite, independently of their tasks or specialisation. Based on the number of times specific behaviours were observed in a delivery partner during an experimental phase, a frequency measure was developed and applied as shown in Table A1 and Table A2.

As well as the behavioural markers, the researchers made direct qualitative observations of Take 5–related activity, other safety activities, and work performance. Informal on-site interviews were conducted with workers and supervisors to confirm and supplement the information gained from observations. Each fieldwork day, the researcher would usually go over to each group and try to engage with someone. Usually this would be with a person in a leading role within that group. After that, the researcher might engage with others in the group, especially if the group was spread out over multiple areas or tasks. Over the course of the whole study, the researcher would aim to cover all roles and tasks, of course considering whether it is feasible to engage with people in any given moment. These informal interviews largely looked like normal conversations where a person shows interest in the other person’s work. The first topic would usually be what the person was engaged with and what was going on that day, followed by whether there were any special concerns. In turn, this would branch out to other topics, such as things that have come up in previous interactions, that stand out to the researcher, or Take 5 and other safety policies.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Setup Verification

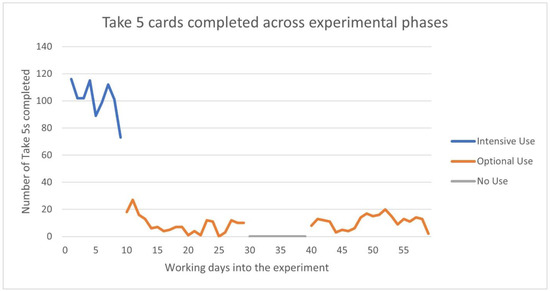

The first question to be addressed was whether the experimental phases had the intended effect of concentrating and diminishing Take 5 use. To assess this, we plotted the number of all Take 5 cards completed across all delivery partners over the time of the experimental phases. Weekends and holidays were taken out, as there was very limited work activity on those days.

As can be seen from Figure 1, the number of Take 5 cards completed fits with the general experimental design. The intensive phase had the highest number of cards completed, with an average of 101 per day, and a standard deviation of 13.6. Note that this is significantly higher than the organisational baseline of approximately 100 cards per month and represents close to full compliance with the agreed goal of three cards per worker per day.

Figure 1.

Take 5 usage over time.

The optional phase after the intensive phase had an average of 8.7 cards per day, with a standard deviation of 6.6. During the no-use period, management reported no Take 5 cards being completed. The optional phase following the no-use phase had an average of 11.0 cards per day and a standard deviation of 5.0. As full compliance with any policy was not expected, the data resemble what would be expected with varying organisational policies around Take 5.

The qualitative observations and interviews also found that, in general, workers followed the instructions of the experimental phases. During the intensive period, workers were observed to complete Take 5 cards frequently and would complain more about having to complete the Take 5 activity. During the optional phase, there were still people completing Take 5 cards, but clearly fewer.

During the no-use phase, Take 5 was not part of everyday work. However, contradicting the data reported by the site management, the researcher identified two instances where workers were completing, or had completed, Take 5 cards. These cases will be elaborated on in the subsequent sections, but they were explicitly recognised as not being like everyday work. Overall, this suggests that the intended variation in Take 5 use between phases was achieved, although it also shows that the number of Take 5 cards reported through administration processes can deviate from the number of Take 5 activities completed on site.

4.2. Qualitative Observations

4.2.1. Opinions about Take 5

At the beginning of the intensive phase there appeared to be a general acceptance that Take 5 was useful and an expectation that Take 5 would be performed as agreed. However, during the trial there were no people that explicitly considered that completing a Take 5 was helpful for themselves in terms of improving their safety, at least in the moment they were asked about it. While some people said that Take 5 could be helpful, this was not for them personally, or not for that task they were currently engaged in. It was always useful for other people or other tasks.

We propose that this form of pluralistic exceptionalism can be referred to as the “Take 5 Effect”, but for the sake of clarity we will refer to it as “Not for Me” throughout this discussion. A Not for Me Effect is where the majority of a population publicly support a rule or practice, despite a private belief that the practice is unnecessary, because they believe that the practice is necessary or helpful for other people. The Not for Me Effect mirrors the existing concept in social psychology of “pluralistic ignorance” [26], where the majority of a population publicly accept an idea despite private disbelief in that idea, because they (incorrectly) believe that the idea has majority support. Pluralistic ignorance, exemplified by the story “The Emperor’s New Clothes” has been used to explain the perpetuation of harmful beliefs and practices even when every individual can observe the true state of affairs.

When asked why they did not personally benefit from Take 5, experienced operators and supervisors referred to their own skills and suggested that the practice was of more benefit for novices learning about safety. When asked if they themselves had learned in this way, they responded that this was not the case. Most experienced workers said that they had learned through mentoring rather than through structured safety activities such as Take 5. Some participants recognised the Not for Me Effect as they articulated their own experiences and offered as an explanation that industry changes had reduced the effectiveness of mentoring, requiring replacements such as Take 5.

Another way in which the Not for Me Effect manifested was in terms of which tasks benefited from a Take 5. Workers suggested that a Take 5 could make sense for other, riskier tasks such as working at heights or in confined spaces—tasks they were not involved in at the time. However, when workers were actually engaged in these tasks, and in high-risk work more generally, they did not consider Take 5 helpful in improving safety. The Not for Me Effect was a pattern across worker and supervisor opinions expressed during the trial and is consistent with our observations from other research projects with different organisations. Support for Take 5 rests on a belief that Take 5 helps other people or other tasks, not on the belief that it helps me, today.

The most common reason given when workers expressed negative sentiment towards Take 5 was the time taken to complete the task. The name Take 5 was believed to imply that one card would take about 5 min. Some workers took significantly longer to fill in a Take 5. At the extreme, one older worker was observed to spend 30 min filling in a Take 5 card. This included some distractions and the person having to switch their attention between the Take 5 and other people. This might mean he in fact spent less than 30 min precisely on that card, but it also meant the requirement to complete Take 5 disrupted and delayed other people, as others needed to wait as he switched between tasks. A significant factor in how fast people completed their Take 5 cards was their reading and writing skill. Low literacy was more common among older workers. The people who most strongly expressed their discomfort with the requirement to complete Take 5 were also the people who took the longest to complete the cards.

4.2.2. Method of Use of Take 5

Prior to the fieldwork on this project, but after consultation with managers and safety staff, the researchers assumed that Take 5 cards would mostly be completed right at “natural breaks”—before the start of a job, after a rest break, when moving to a new location, or when switching to a new phase of the work. These are the times when workers might encounter new hazards and when cues for hazards are available to them. The worker would look at the environment for cues while completing the Take 5, would record hazards, and would record the intended controls.

Whilst the workers agreed that this was how Take 5 should be used, they did not in fact fill out Take 5 cards right before starting a task. We observed three alternative strategies:

- completing in advance;

- completing after work; and

- completing on behalf of someone else.

Completing the Take 5 card in advance was by far the most common strategy. Many workers would pre-fill their cards before arriving at the work site. One worker showed the researcher a whole Take 5 card booklet that was already prefilled. Another worker, a truck operator, said that he fills all three Take 5 cards in the morning before he starts work. His work was quite routine and always included similar hazards and controls, and as such he did not feel the need to fill them in during the day. The researcher also observed pre-filled Take 5 cards lying around the canteen with future dates written on them. As the examples show, completing Take 5 in advance was often combined with batching—that is, completing multiple Take 5 cards at once. This saved time, made the act of completing Take 5 less disruptive, and allowed the Take 5 to be completed in more comfortable settings.

The opposite strategy was to complete Take 5 after completing a job or shortly before finishing a task. The Take 5 would then be written to match the task that had just been completed. This strategy was only observed a handful of times. From our observations, we conclude that this was partly motivated by a reduction in effort required to complete the Take 5. Rather than having to think about what to do, workers could recognise what they had done. However, because of the little data we had on this strategy, this explanation should be treated as tentative.

The third strategy for completing Take 5 was having people complete other people’s Take 5 cards. This worked by having one worker simultaneously complete the Take 5 cards for everyone in a group. This saved time, as one person could fill in all cards at once, reducing the total time needed to complete the Take 5 activity, while others could already start preparing or working on other tasks. There were no such instances observed where others in the team paid attention to what was written on the Take 5 cards, where the person who completed the Take 5 cards would inform others about hazards present, or where the person completing the cards would suggest changes on how to conduct the work.

It is tempting to dismiss these strategies as unusual or deviant performance of Take 5. However, all of the observed practices are consistent with what the workers said happened outside of the study. Due to the nature of infrastructure construction contracting, even permanent employees of a delivery partner are exposed over time to a wide range of safety practices under the oversight of many clients and principal contractors. The researchers have also heard and seen similar practices surrounding Take 5 cards on other sites and industries.

The only thing that is notable in this study is that these practices were observed consistently under conditions where the workers had agreed to make a sincere effort to use the Take 5 cards appropriately for a short period (the two-week intensive use phase) and under conditions where the use of Take 5 cards was either not strongly enforced (the baseline) or explicitly optional (the optional use phases). This is strong evidence that these practices represent the normal worker experience of using Take 5 cards and would appear under most, if not all, organisational circumstances.

5. Analysis

5.1. Analysis Overview

This section follows the same internal structure as the “Rationale” section of the paper. For each hypothetical function identified in that section, we seek to establish the following:

- Do the supervisors or workers believe that this is a function of Take 5?

- Are the conditions necessary for this function to be present?

- What is the evidence for and against the operation of the function?

5.2. Planning the Safety of Work

Site management, supervisors, and operators all expressed an understanding that Take 5 was a planning tool. One of the clearest examples of this view came from a site supervisor, talking about how he convinced crews to use Take 5 cards:

“I tell the guys, look you might think [Take 5] is a waste of time, but if you use it properly, you might come up with a better more efficient way of doing a task. So you filling a [Take 5] will make you think of a better way of doing work. I try to use reason with them”.

Outside of site management, this view was also implicitly evoked in arguments against the ubiquitous use of Take 5. Workers often argued that Take 5 made more sense for some tasks than for others. The general form of this argument was that for riskier jobs, filling in a Take 5 could be justified as time and effort to make the task safe. Workers would then support this argument by referring to either the severity of what could go wrong or the unfamiliarity of the job.

Whilst both severity and unfamiliarity were mentioned frequently, unfamiliarity was the more common and strongly held concern. When workers were asked to provide examples of jobs for which a Take 5 would be useful, they responded by discussing uncertainty and unfamiliarity. This finding was supported by the fact that workers who performed high-risk tasks such as working in confined spaces did not have an increased belief in the usefulness of Take 5 for their own work.

Both the explicit belief in Take 5 as a planning tool and the implicit understanding that Take 5 is most effective for unfamiliar tasks point to a consistent belief in the rationale that Take 5 is useful for planning the safety of work. However, the findings do not support the idea that Take 5 makes a difference in task planning. There are three specific lines of evidence that contradict this function.

The first line of evidence is the previously mentioned set of strategies for completing the Take 5 cards. For Take 5 to operate as a planning tool, the card must be completed prior to the start of work, but after the local conditions of the work are known. Take 5 cards that are completed in batches, prior to arrival on the work site, or after the performance of the work cannot be effective planning tools.

The second line of evidence is the disconnect between what is written on the cards and how the work is performed. It was common for workers to write down controls that were not put in place, and to put in place controls that were not written down. Whilst the planning function does not strictly require that the card is an accurate record, with such common discrepancies it is hard to imagine that the act of completing the Take 5 influenced the planning.

The third and most telling line of evidence is that, across the entire research project, there were no cases observed where workers visibly changed plans in response to completing a Take 5. We know, through the heedfulness marker system, that changed plans were observable. For example, workers were observed to go back to the workshop after viewing the worksite, realising that they needed a different tool to complete a job, or in response to comments from colleagues or supervisors. However, such changes never occurred during or directly after completing a Take 5.

In response to this rather surprising finding, we considered the possibility that Take 5 has influence on a smaller scale, influencing very local factors such as the positioning of tools around a worksite to prevent them falling or being in the way while conducting work. This possibility was contradicted by the level of detail written on the cards. Both hazards and control were routinely described using general wording that would fit any environment, rather than with positional details that might influence planning.

We also approached the problem from the other direction, collecting stories from workers and supervisors about unusually conducted and well-planned jobs. These stories confirmed that safety concerns—including the types of hazards usually documented on the Take 5 cards—did indeed influence the planning of work. However, these stories did not establish a link between either the recognition of the safety concern or the change in activity and the use of Take 5 cards. The planning for the change had already taken place by the time workers arrived on site for the job.

While there was an expressed belief that Take 5 functions as a planning tool, the combination of timing of Take 5 completion, lack of linkage between cards and work environment, lack of instances of Take 5 leading to changed planning, and lack of instances of changed planning being attributed to Take 5 make it unlikely that Take 5 has an effect on safety through improved planning around hazards.

5.3. Increasing Heedfulness

Heedfulness was not seen as the primary purpose of Take 5 but was commonly recognised as a hypothetical benefit. Most frequently, this rationale presented in reverse through the Not for Me Effect. For example, supervisors would say that because of their experience and because they had led a toolbox talk that covered the work hazards, they did not need to complete a Take 5 themselves.

By saying in this way that they did not need the Take 5, supervisors and other experienced workers revealed an implicit belief that Take 5 works—or at least can be justified—based on increasing hazard awareness. However, the findings do not support the idea that Take 5 makes a difference in heedfulness.

The primary line of evidence for this finding is that whilst the volume of Take 5 use varied between phases of the project, no differences were found across the phases on any of the heedfulness measures, even at the subgroup level. There was no sign that the intensive, optional, or no-use phases of Take 5 made a difference to:

- workers’ attention to their own personal comfort, health and safety;

- workers’ attention to others around them;

- workers’ attention to rules and work requirements;

- workers’ attention to the environment, including worksite hazards;

- workers’ attention to, and use of, tools and equipment; or

- workers’ concern for the timing and pace of the work.

For a full overview of the measures and findings, see Appendix A. This also means that there were no indications of lingering or sustained heedfulness effects in individuals who had just completed unusually high or low numbers of Take 5 cards.

As an alternative to the hypothesis that Take 5 cards directly increase heedfulness, we considered whether the general practice of Take 5 creates a persistent habit of heedfulness that persists after Take 5 use declines or disappears. This possibility is unlikely. The completion of Take 5 cards was quite low during both the baseline period and the optional phases, and there were workers who never or almost never completed a Take 5. The period of intensive Take 5 use would have been a significant change for these workers, and yet no increase in heedfulness was observed during this period, and no decline in heedfulness was observed afterward.

The only possibilities this allows for are that Take 5 has no effect on heedfulness, or some previous period of Take 5 enforcement was so effective as to create a strong and lasting habit that our six-month study could not dent. If this really was the case, then a one-off training exercise would be likely to be just as effective, and a lot more efficient, than a policy mandating the ongoing use of Take 5.

Whilst there was an implicit belief that Take 5 can improve heedfulness (for other people), the lack of variation in heedfulness across this project makes it unlikely that Take 5 had either a positive or a negative effect on heedfulness.

5.4. Education

Education was never explicitly expressed as a primary function of Take 5 during the study, but it was acknowledged as something Take 5 could influence. Multiple experienced operators would say that Take 5 was not necessarily relevant for them, but it might be helpful for novices. These experienced operators seemed to consider planning around hazards as the main intended purpose of Take 5, where this guided approach could also be helpful for education of younger workers.

The study design was not ideal for assessing educational effects. Both the overall length of the study and the length of the individual phases were too short to capture incremental change over an extended period, and there was no systematic focus on individuals. In addition, there were too few novices on site to make even ad hoc observations about educational effects. However, there were some general observations that challenged the possibility that Take 5 works as an educational tool.

Firstly, the way operators completed Take 5 made it unlikely they learned through this process. With operators completing Take 5 without seeing or thinking about the specifics of the work tasks, they are unlikely to think of anything new. As such, it would not reinforce knowledge of site hazards. It was even unlikely that the Take 5 was reinforcing information that was listed directly in the booklet, as many operators did not seem occupied by the items of a Take 5 and mostly responded to the location on the page of the boxes rather than the content of the questions. One worker joked to the researcher “Do you want to see me do one blind?” Workers were more focussed on getting the Take 5 done rather than thinking about the content of the Take 5, let alone learning new information.

Secondly, even when the Take 5 was completed on site, there was a poor correspondence between what workers recorded and the actual environment and safety controls. It was quite common for workers to list hazards that were not present for the specific task, write down controls that were not put in place, and put controls in place that were not listed. This means that whatever was being reinforced through the Take 5 did not translate to what was done in practice, nor what was most relevant for a task.

Thirdly, no one considered the Take 5 a meaningful mechanism through which they had learned themselves. Most workers mentioned that Take 5 was not around when they started in the industry. Most mentioned they had learned through mentoring and considered this a better way to learn. In addition, people said that being exposed to different jobs was more educational. Novices were less negative about Take 5 but did not talk about Take 5 as something with educational value. They considered Take 5 something that was expected of them, not something done for their own benefit.

Fourthly, Take 5 lacks the specific information and feedback necessary to promote learning. Workers raised this concern in regard to heedfulness and planning, but this point was probably more relevant for the educational rationale. Their critique was that the items and the hazard control section were unable to lead someone to new conclusions. The items ask whether someone has the appropriate tools or qualification, but not what the appropriate tools and qualifications are, let alone whether they are special requirements for that task. This means that if a person does not already know that a job has special tools or qualification requirements, they are likely to believe their qualifications and the tools they have chosen are appropriate for the job. If the person knows about the requirements for tools or qualifications for a job, they would not need the Take 5 to remind them. A similar argument was made around listing hazards and controls. People only recognise things they know to be a hazard, and as such would already have recognised those things as a hazard without a Take 5. The Take 5 does not inform someone of whether something is a hazard or of what is an appropriate control for that hazard. For heedfulness and planning functions, this argument is at least not absolute. Theoretically, Take 5 could lead people to slow down, prompt someone to remember, or encourage them to take an extra look. The argument is stronger against the education function. Slowing down doesn’t miraculously create information or feedback. Without either, people cannot come to new insights by Take 5 alone.

We acknowledge the possibility that Take 5 could play a role in education, but it is unlikely it currently plays this role. The way Take 5 is used in practice, the lack of recognition of its effect on personal development, and lack of a specific knowledge and feedback mechanism all point to Take 5 not working as an educational tool. These arguments are specific to the implementation and supporting context of this project and might be mitigated by a different style of Take 5 under other circumstances.

5.5. Distributed Hazard Identification

On this site, there was no indication that people thought Take 5 played a direct role in a distributed hazard identification process. Site management did not systematically read through completed Take 5 cards and look for (new) hazards listed. Workers did not consider the information they wrote on Take 5 cards as influencing anybody but themselves. As such, it is safe to say that Take 5 did not contribute to a formal distributed hazard identification process on this site. This limits the conclusions we can draw about this function, as our expectation is that workers normally adapt systems towards desirable functions, even beyond what the systems are designed for. Where there is no intent to achieve the function, it is unsurprising that the function is not being achieved. However, we did identify some factors that would make Take 5 poorly suited for this function.

The first factor is that the process through which Take 5 cards are completed makes it impossible for them to capture new hazards as they arise. With workers often completing Take 5 cards before arriving on the job site, they would not capture new, unusual, or specific hazards. The hazards written down would be generic and not reflect the “on-the-ground” experience.

The second factor is that the hazards and controls that are written down are an inaccurate reflection of what workers saw and did. It common for workers to list hazards that were not particularly relevant for their job and not to list all possible hazards that were present. In addition, workers would write down controls that they did not put in place, or put in place controls they did not write down on their Take 5. For example, people might be using their radio to coordinate vehicle interactions, without listing their radio or even listing vehicle interactions as a hazard. As such, the Take 5 card formed a poor record of what hazards operators faced and what controls were put in place. What was and was not mentioned was not even a random selection of the available information, as workers almost exclusively wrote down hazards and controls that were easy to explain in a few words. For example, operators might put care into positioning their tools in a way that they were unlikely to interfere with others when working in narrow elevated pathways, or electricians might use a method and tools to minimise entry into a confined space. While workers took effort to enact and communicate these strategies with their colleagues, they were not written down. For many of these strategies, it would have been impossible to describe them in the little space Take 5 cards offer, let alone keep them understandable for someone analysing the Take 5 card afterwards. Even when Take 5 cards are used as and when intended, it is unlikely they are representative, exhaustive, or necessarily capture a meaningful level of detail.

The third factor is the lack of uniform understanding and classification of hazards and controls. Even between people from the same delivery partner, there were different ideas of what counts as a hazard and control around a specific task. There were disagreements whether certain tools should be considered “hot works” and should be considered a fire hazard, and in turn what kind of controls were appropriate. In addition, there were different ideas as to what counted as having a fire watch, in terms how close such a person had to be and whether they could have additional work functions at the same time. This means that when looking at the same job, people might come to different conclusions about what hazards are present and what controls have been put in place. Thus, even when all individuals are fully self-aware of the concerns in their area and how they respond to them, this does not mean what they write down on the Take 5 cards can be uniformly interpreted by an analyser.

Whilst Take 5 was not intended as a distributed hazard identification tool on this site, and so it is unsurprising that it did not work effectively in this way, the challenges would extend to most applications of Take 5. It seems impossible to get all individuals to use the process correctly, have them fully self-aware of all of the safety hazards they are responding to, and have them uniformly classify the hazards and controls. For a single specific hazard or task, this might be possible, but that is not how Take 5 is generally used.

5.6. Demonstration of Due Diligence

There was some belief that Take 5 operates directly as a means of demonstrating due diligence. The most clearly articulated version of this belief came from one subcontractor. He argued that Take 5 does not satisfy any specific legislation or policy requirement but serves generally to create evidence of diligence. Legislation and policies change over time, and an individual or small contractor cannot keep up with these changes. What they can do, however, is undertake activities such as Take 5, which create an evidence trail that can be referred to later. So, if an accident happens and it goes to court, they can worry less about specific regulations and make a more general case that they were being diligent about safety.

This specific concern about prosecution was mentioned several times, but more common was a vaguer understanding that Take 5 would provide “protection” in the event of something going wrong. This belief does not directly match the due diligence function as described in our Rationale section, because the arrows of perceived accountability did not flow from the workers, through the management, to external stakeholders. Instead, people saw Take 5 cards as a way to shield themselves as individuals against blame or criticism arising from inside the company. The exact nature and source of this threat was either unspecified or poorly articulated, leading us to conclude that the Take 5 is not a specific defence against a specific threat, but rather a “social defence”, providing a mechanism for people to support the reasonableness of their actions against any form of future criticism.

The clearest examples of the use of Take 5 as a social defence were seen during the “no use” phase of the study. During this phase, a crew was observed filling in Take 5 cards after they had been instructed not to. When the researcher asked why they were completing the cards, they justified doing this because they were trying to “cover their ass”, since the job they were about to do was risky and they had not done it before. There was an increased chance that something might go wrong, and they did not want to be blamed if it did. On another day during the no-use phase, the same crew was involved in an incident where heavy pipes had fallen off a crane. After this incident, they had been instructed by the site management to fill in a Take 5 again, to “cover their ass”.

During a separate part of the broader safety clutter project, a trial was conducted, reducing the use of written site permits. During this trial, site managers were observed telling workers to put extra focus on Take 5 cards, as there were no permits to cover them if an accident happened. This instruction was not universally followed, but some operators put significantly more effort into Take 5 completion during the reduced permit trial.

Throughout all phases of the Take 5 study, self-protection was used as an argument to convince other people to comply with the practice. Usually, the threat was unspecified, but the circumstances requiring protection were either an accident or “something going wrong”. In one exception, during the intensive-use phase, workers were complaining to site management about filling in Take 5 cards. The supervisor argued that the Take 5 was helpful because, without it, they would have to complete more or longer formal paperwork, such as lifting plans. The supervisor sold the Take 5 not as a protection against blame, but as a shield against more onerous bureaucratic requirements.

In assessing this function, it is important to remember that this study was set up to determine whether and how Take 5 contributes to safety, not to examine the role of Take 5 in blame allocation. Whilst we heard anecdotes about the presence or absence of Take 5 being used to blame workers, and even of supervisors visiting workers in hospital to check that they had completed their Take 5, we are aware that stories of this nature can grow well beyond the original facts.

What we can conclude, however, is that the anecdotes are part of a broader social narrative in the workplace that workers are in constant danger—not of physical harm, but of unfair accusation that they did not live up to their safety obligations. Along with this narrative is a belief in the power of paperwork as protection against this danger. Even a card that was transparently part of a batch written far removed from the point of work, describing controls that never existed and ignoring controls that did exist, can form a shield against blame.

Because of this narrative, even when the site management explicitly said workers should not fill in Take 5 cards, some workers adapted around the new rule. A few deliberately ignored the instruction, whilst others relied more heavily on other forms of paperwork. Just as, during the permit trial, workers were exhorted to write more on the Take 5 cards, when the Take 5 cards were taken away, workers wrote more down on other types of paperwork, such as the permits. This suggests that workers care about this concern out of their own interest, rather than an attempt to comply with site requirements.

The function of “social defence” does not contradict the possibility that workers face genuine risk of specific blame. We confirmed, on this project and other projects, that incident investigators do examine Take 5 records. This includes investigators from regulators, principal contractors, and subcontractors. Take 5 cards are used as evidence of both awareness of specific hazards and to make inferences about the general diligence of a worker or supervisor. For example, the presence or absence of Take 5 cards can be used to conclude that someone has been careful or diligent in the lead-up to an accident.

As a consequence of these investigation practices, workers have shared with us that it is common practice to check, update, or complete a Take 5 from scratch after an incident happens, to ensure that the card matches the situation at hand. In turn, this can include modifying the environment to make it look like more controls were in place. This hindsight management of the scene after an incident is the only occasion any worker told us about changing the worksite in response to what was written on a Take 5 card.

6. Discussion

6.1. If Take 5 Is Not Effective, Why Is It Used?

Our goal in this paper was to assess whether Take 5 improves safety, and if it does not, to provide an alternate explanation for why organisations continue to use Take 5. Our analysis in the previous section provides a clear answer to the first question. We are confident that Take 5 does not contribute to safety, at least not through any of the functions by which Take 5 is understood to work.

We also do not believe that the evidence that we have presented will come as a surprise to most people familiar with Take 5. We designed and executed a study to systematically test and explore criticisms of Take 5 that have been circulating in the academic and professional safety communities for a considerable time.

So why does Take 5 persist as a safety practice?

In our analysis of the due diligence function, we concluded that Take 5 operates as a form of social defence, allowing both workers and supervisors to protect themselves against future criticism of their actions. Here, we extrapolate tentatively to suggest some further explanations.

As well as a social defence, and instead of due diligence in the regulatory sense of the term, Take 5 can act as evidence of a sort of general regard or care for safety. This idea might explain why Take 5 cards were completed during the “no use” phase. Besides saying they were trying to cover their ass, people in this team used the words “better to be compliant than sorry”. The use of the word “compliant” is odd at first notice, as requirements for Take 5 were explicitly taken away, and these workers were aware of that. However, if “compliant” is understood as showing general regard for safety and having followed a good process, the statement makes more sense. Showing that one followed a trusted process is associated with compliance and auditing in general [9,27]. Take 5 could still make the team look like they followed a trustworthy safety process, even if it was not an explicit requirement.

This could also explain the practice of filling in the Take 5 after a task is completed. In terms of planning, heedfulness, and education, completing a Take 5 after the work is done has no value. No work is being planned, and there is no need to recognise new hazards nor a need to learn if someone already successfully adapted around the hazards present. In terms of shielding against blame, this still makes no sense, as by this point the job has been successfully completed with no incident. However, in terms of showing regard for safety, Take 5 can still matter. Being known as a person who fills in the Take 5 can help make the case that someone is a diligent person in general. To support this hypothesis, completing or updating a Take 5 after a job was complete was only done by a few individuals, but they were observed to do it often. One person who was most consistently observed to complete Take 5 cards after the completion of a job was known by other workers and supervisors to be very diligent in terms of paperwork in general. This suggests this behaviour is known to have the effect of looking diligent, which makes it more likely someone does it deliberately. This desire to look good could be driven not out of fear, to avoid future disciplinary actions, but also out of ambition, fostering career advancement.

The role of safety advisor or safety supervisor is one of the few career paths for a worker in a physically strenuous job to move “off the tools” and into an office environment. It is likely that workers who participate in activities such as Take 5 as a way of demonstrating diligence may continue to promote this practices to foster their own advancement.

At an organisational level, we suggest that belief in the efficacy of Take 5 arises from the conflation of accountability and safety. Large organisations frequently experience incidents or accidents where the organisation sincerely believes that it has provided workers with all of the conditions necessary for successful work, only to be “let down” by workers who are careless, take short cuts, or fail to successfully adapt to local conditions that the wider organisation was unaware of. All of the hypothetical functions of Take 5 offer a tantalising promise of closing the last gap between systems and behaviours. Such thinking is explicit in documents about the proto-Take 5 systems. Sellar, for example, describes the ever-decreasing proportion of accidents ascribed to “unsafe conditions” and the need for an approach (in this case, the Five Point Safety System) that can tackle the problem of “unsafe acts” by altering the “minds of men” at the point of work [13].

Whilst organisations may adopt practices that seek to influence frontline behaviour, they can never be sure that these practices are working, either in general or for any specific instance of work. This causes organisations to rely on safety adjacent measures, such as how well documented things are. The increase in auditable traces—the “evidence” that workers are diligent and that controls are in place—creates a perception that work is both more transparent and under greater control. However, in practice, the documentation does not provide meaningful information and becomes part of a routine that relieves anxiety without resolving the original issue. See Wastell [9] for a detailed discussion of how branded methods can fulfil this anxiety-relieving role and Power [28] for a description of how the need for auditable traces has increased across many aspects of work.