Errors in Clinical Practice and Organizational Constraints: The Role of Leadership in Improving Patients’ Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

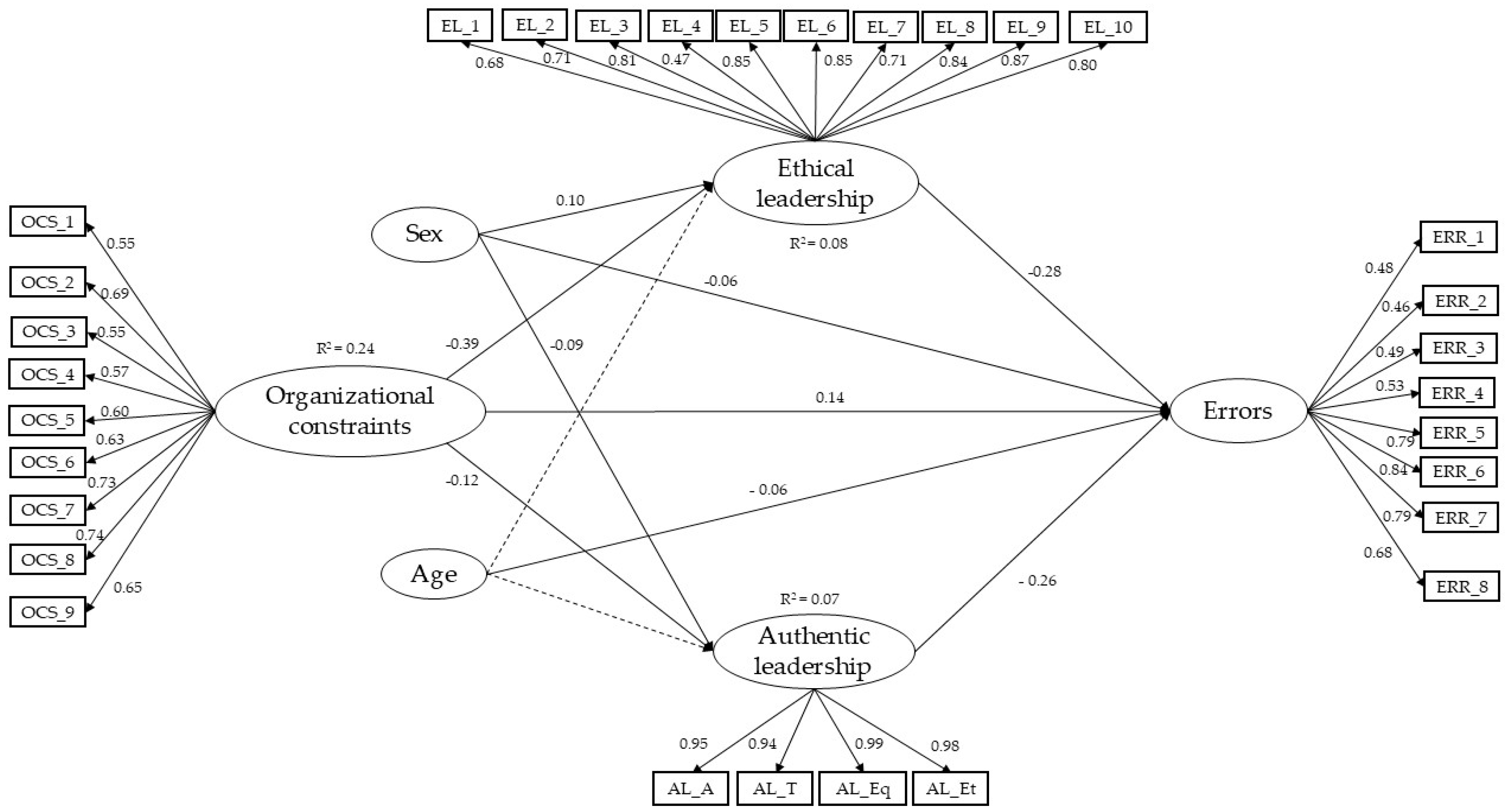

- H1, H2: High levels of OCSs have a negative relationship with nurses’ perception of their head nurses’ ethical and authentic leadership styles.

- H3: High levels of OCSs in organizations have a positive relationship with errors within healthcare organizations.

- H4, H5: Ethical and authentic leadership styles of head nurses have a negative relationship with errors in healthcare organizations.

- H6, H7: The ethical or authentic leadership styles of head nurses have a mediating role in the relationship between OCSs and nurses’ errors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Results of Correlations Between the Variables

3.2. Results of the Structural Equation Model

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AL | Authentic leadership |

| ALQ | Authentic Leadership Questionnaire |

| EL | Ethical leadership |

| NCES | Nurses Care Errors Scale |

| OCS | Organizational constraints |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Structural equation model |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement |

References

- Aydogdy, A.L.F. The Impact of Organizational Culture on Nursing: A Comprehensive Analysis. World Acad. J. Manag. 2024, 11, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harhash, D.E.; Ahmed, M.Z.; El-Shereif, H.A. Healthcare Organizational Culture: A Concept Analysis. Menoufia Nurs. J. 2020, 5, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmreich, R.; Merritt, A. Culture at Work in Aviation and Medicine: National, Organisational, and Professional Influences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, J.; Jackson, D.; Mannix, J.; Davidson, P.; Hutchinson, M. The importance of clinical leadership in the hospital setting. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2014, 6, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.S.; Minjeong, A.; Myoung Lee, C.; Ae Kyong, L. Factors Influencing Quality of Nursing Service among Clinical Nurses: Focused on Resilience and Nursing Organizational Culture. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2017, 23, 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Srimulyani, V.A.; Hermanto, Y.B. Organizational culture as a mediator of credible leadership influence on work engagement: Empirical studies in private hospitals in East Java, Indonesia. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faremi, F.A.; Olatubi, M.I.; Adeniyi, K.G.; Salau, O.R. Assessment of occupational-related stress among nurses in two selected hospitals in a city southwestern Nigeria. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 10, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.G.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Boudrias, V. Work environment antecedents of bullying: A review and integrative model applied to registered nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 55, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Jex, S.M. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.H.; O’Connor, E.J. Measuring work obastacles. In Facilitating Work Effectiveness; Schoorman, F.D.S.B., Ed.; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Enwereuzor, I.K.; Ukeatabuchi Echa, J.; Ekwesaranna, F.; Ezinne Ibeawuchi, W.; Uche Ogu, P. Interplay of organizational constraints and workplace status in intent to stay of frontline nurses caring for patients with COVID-19. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 18, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, L. Communication failures in the operating room: An observational classification of recurrent types and effects. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2004, 13, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, K.; Petitti, D.B.; Fong, K.T.; Bonacum, D.; Brookey, J.; Graham, S.; Lasky, R.E.; Sexton, J.B.; Thomas, E.J. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am. J. Surg. 2009, 197, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronovost, P.J.; Freischlag, J.A. Improving Teamwork to Reduce Surgical Mortality. JAMA 2010, 304, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baka, Ł.; Bazińska, R. Polish adaptation of three self-report measures of job stressors: The Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, the Quantitative Workload Inventory and the Organizational Constraints Scale. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2016, 22, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sili, A.; Fida, R.; Zaghini, F.; Tramontano, C.; Paciello, M. Counterproductive behaviors and moral disengagement of nurses as potential consequences of stress-related work: Validity and reliability of measurement scales. Med. Lav. 2014, 105, 382–394. [Google Scholar]

- Zaghini, F.; Biagioli, V.; Caruso, R.; Badalomenti, S. Violating organizational and social norms in the workplace: A correlational study in the nursing context. Med. Lav. 2017, 108, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, M.; Barber, N.; Franklin, B.D. Facilitators and Barriers to Safe Medication Administration to Hospital Inpatients: A Mixed Methods Study of Nurses’ Medication Administration Processes and Systems (the MAPS Study). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigl, M.; Muller, A.; Zupanc, A.; Glaser, J.; Angerer, P. Hospital doctors’ workflow interruptions and activities: An observation study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011, 20, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann, P.; Reddersen, S.; Wehner, T.; Rall, M. Prospective memory failures as an unexplored threat to patient safety: Results from a pilot study using patient simulators to investigate the missed execution of intentions. Ergonomics 2006, 49, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wears, R.L.; Woloshynowych, M.; Brown, R.; Vincent, C.A. Reflective analysis of safety research in the hospital accident and emergency departments. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanyuan, Y.; Jie, C.; Liuping, P. The impact of adverse nursing events on nursing psycology. J. Adv. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 30, 617–619. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Ai, C.; Wang, M.; Chen, X. Nurses’ Risk Perception of Adverse Events and Its Influencing Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2024, 61, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arifin, F.; Troena, E.; Djumahir Rahayu, M. The influence of organizational culture, leadership, and personal characteristic towards work engagement and its impacts on teacher’s performance (A study on accredited high schools in Jakarta). Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2014, 3, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, G.G.; Tate, K.; Lee, S.; Wong, C.A.; Paananen, T.; Micaroni, S.P.; Chatterjee, G.E. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 85, 19–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabona, J.F.; van Rooyen, D.; ten Ham-Baloyi, W. Best practice recommendations for healthy work environments for nurses: An integrative literature review. Health SA Gesondheid 2022, 27, a1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, G.G.; Lee, S.; Tate, K.; Penconek, T.; Micaroni, S.P.; Paananen, T.; Chatterjee, G.E. The essentials of nursing leadership: A systematic review of factors and educational interventions influencing nursing leadership. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 115, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraca, E.; Zaghini, F.; Fiorini, J.; Sili, A. Nursing leadership style and error management culture: A scoping review. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2024, 37, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, S.Q.; Miller, M. Communication and the Healthy Work Environment. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2013, 43, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.A.; Giallonardo, M.L. Authentic leadership and nurse-assessed adverse patient outcomes. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013, 21, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keselman, D.; Saxe-Braithwaite, M. Authentic and ethical leadership during a crisis. Healthc. Manag. Forum. 2021, 34, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M.; Mirjalili, N.S. Ethical leadership, nursing error and error reporting from the nurses’ perspective. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, F.; Furtado, L.; Mendonça, N.; Soares, H.; Duarte, H.; Costeira, C.; Santos, C.; Sousa, J.P. Predisposing Factors to Medication Errors by Nurses and Prevention Strategies: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1553–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutra, C.K.R.; Guirardello, E.B. Nurse work environment and its impact on reasons for missed care, safety climate, and job satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2398–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, J.; Zaghini, F.; Mannocci, A.; Sili, A. Nursing leadership in clinical practice, its efficacy and repercussion on nursing-sensitive outcomes: A cross-sectional multicentre protocol study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 3178–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnese, M.L.; Zaghini, F.; Caruso, R.; Fida, R.; Romagnoli, M.; Sili, A. Managing care errors in the wards. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.E.; Kotrlik, J.W.; Higgins, C.C. Organizational Research: Determining Organizational Research: Determining Appropriate Sample Size in Survey Research Appropriate Sample Size in Survey Research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2011, 19, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei, A.; Carter, S.R.; Patanwala, A.E.; Schneider, C.R. Missing data in surveys: Key concepts, approaches, and applications. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 2308–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaranelli, C.; Fida, R.; Gualandri, M. Assessing counterproductive work behavior: A study on the dimensional of CWB—Checklist. TPM-Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 20, 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Fida, R. A time-lagged analysis of the effect of authentic leadership on workplace bullying, burnout, and occupational turnover intentions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.; Muthén, B. Mplus User’s Guide (Version 7.0), 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudreau, C.; Rhéaume, A. Impact of the Work Environment on Nurse Outcomes: A Mediation Analysis. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 46, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Bruyneel, L.; Van den Heede, K.; Griffiths, P.; Busse, R.; Diomidous, M.; Kinnunen, J.; Kózka, M.; Lesaffre, E.; et al. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet 2014, 383, 1824–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Saville, C.; Ball, J.E.; Jones, J.; Monks, T. Beyond ratios—Flexible and resilient nurse staffing options to deliver cost-effective hospital care and address staff shortages: A simulation and economic modelling study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 117, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochefort, C.M.; Clarke, S.P. Nurses’ work environments, care rationing, job outcomes, and quality of care on neonatal units. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2213–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Plaza, M.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Martí-Ejarque, M.D.M.; Ferré-Grau, C. Association of Nursing Practice Environment on reported adverse events in private management hospitals: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2990–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Mehta, H. Antecedents and Consequences of Organisational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB): A Conceptual Framework in Reference to Health Care Sector. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- van Kraaij, J.; van Merode, F.; Lenssen, E.; Vermeulen, H.; van Oostveen, C. Organizational Rigidity and Demands: A Qualitative Study on Nursing Work in Complex Organizations. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3346–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.; Luthans, F. High Impact Leader: Moments Matter in Authentic Leadership Development; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Wen, X.; Gou, L. Exploring the Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Nurses’ Moral Courage in China: The Mediating Effect of Psychological Empowerment. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 6664191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaghini, F.; Fiorini, J.; Piredda, M.; Fida, R.; Sili, A. The relationship between nurse managers’ leadership style and patients’ perception of the quality of the care provided by nurses: Cross sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 101, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.; Yu, S. The Relationships Among Perceived Patients’ Safety Culture, Intention to Report Errors, and Leader Coaching Behavior of Nurses in Korea: A Pilot Study. J. Patient Saf. 2017, 13, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nurses’ Characteristics | n (%) | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.37 (10.92) | 18–65 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 440 (18.7) | ||

| Female | 1909 (81.3) | ||

| Non-binary | - | ||

| Civil Status | |||

| Single | 929 (39.5) | ||

| Separated/Divorced | 190 (8.10) | ||

| Married | 1212 (51.6) | ||

| Widow/Widower | 18 (0.80) | ||

| Professional Education | |||

| Regional Diploma | 737 (31.4) | ||

| Nursing Diploma | 243 (10.3) | ||

| Bachelor of Nursing | 1369 (58.3) | ||

| Working Clinical Settings | |||

| Surgery | 239 (10.2) | ||

| Cardiothoracic surgery | 50 (2.1) | ||

| Transplantation Surgery | 53 (2.3) | ||

| Emergency Surgery | 180 (7.7) | ||

| Neurological Surgery | 28 (1.2) | ||

| Orthopedics | 82 (3.5) | ||

| Medicine | 1122 (47.8) | ||

| Neurology | 88 (3.7) | ||

| Urology | 16 (0.7) | ||

| Nephrology | 42 (1.8) | ||

| Geriatrics | 60 (2.6) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 113 (4.8) | ||

| Oncology | 58 (2.5) | ||

| Hematology | 64 (2.7) | ||

| Infection disease | 44 (1.9) | ||

| Pulmonary disease | 84 (3.6) | ||

| Gastroenterology | 26 (1.1) | ||

| Working years | 15.45 (10.71) | 0–45 | |

| Daily working hours | 7.36 (3.12) | 0–13 |

| Pearson’s Correlation (r) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | OCS | EL | AL | |

| OCS | 2.40 (0.73) | 1 | ||

| EL | 4.05 (0.83) | −0.45 *** | 1 | |

| AL | 3.27 (0.92) | −0.41 *** | 0.76 *** | 1 |

| Errors | 1.56 (0.49) | 0.42 *** | −0.24 *** | −0.24 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moraca, E.; Zaghini, F.; Fiorini, J.; Sili, A. Errors in Clinical Practice and Organizational Constraints: The Role of Leadership in Improving Patients’ Safety. Safety 2025, 11, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020057

Moraca E, Zaghini F, Fiorini J, Sili A. Errors in Clinical Practice and Organizational Constraints: The Role of Leadership in Improving Patients’ Safety. Safety. 2025; 11(2):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020057

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoraca, Eleonora, Francesco Zaghini, Jacopo Fiorini, and Alessandro Sili. 2025. "Errors in Clinical Practice and Organizational Constraints: The Role of Leadership in Improving Patients’ Safety" Safety 11, no. 2: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020057

APA StyleMoraca, E., Zaghini, F., Fiorini, J., & Sili, A. (2025). Errors in Clinical Practice and Organizational Constraints: The Role of Leadership in Improving Patients’ Safety. Safety, 11(2), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020057