Assessment of Occupational Health and Safety Management: Implications for Corporate Performance in the Secondary Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

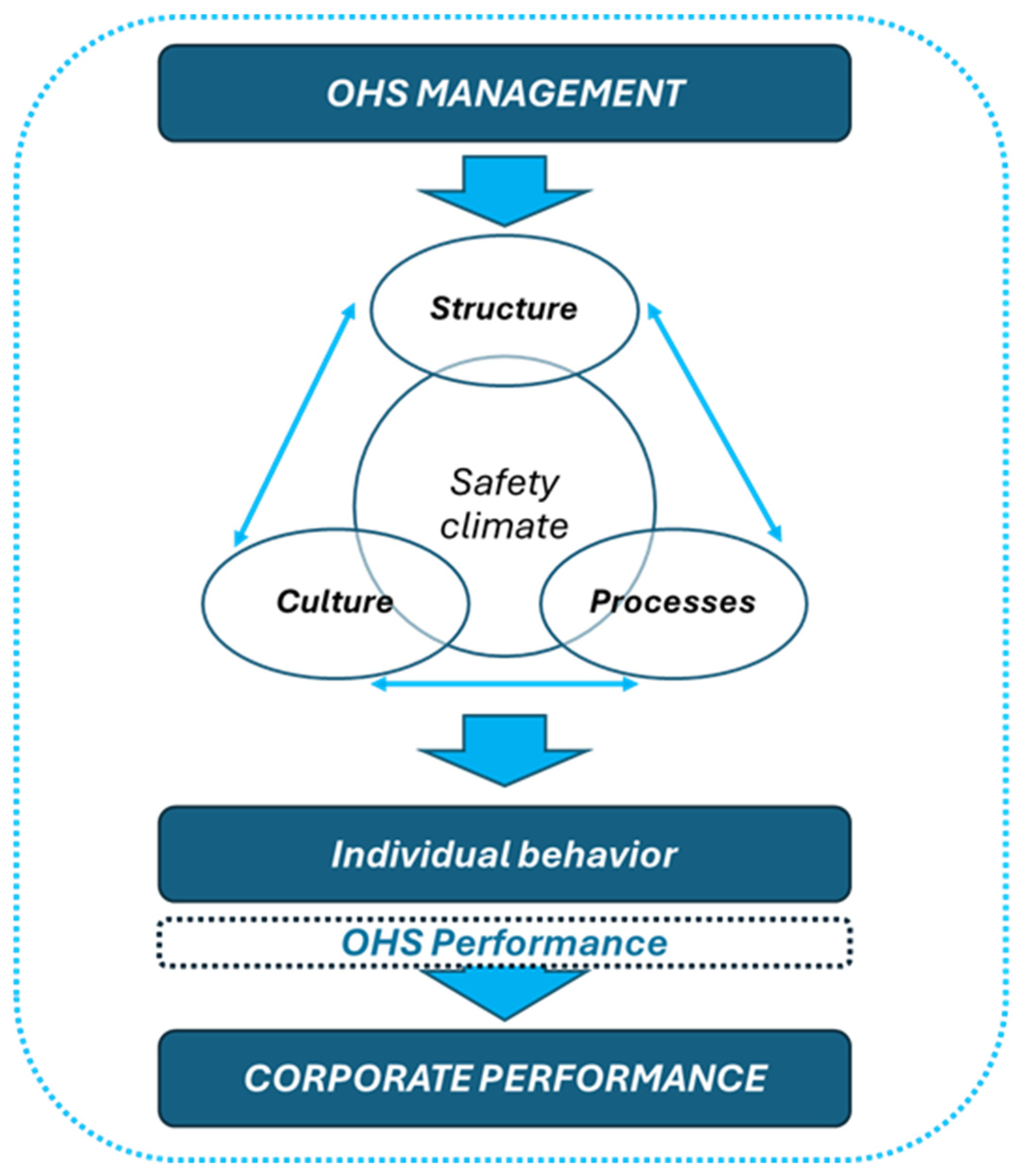

2. Literature Review

2.1. Occupational Health and Safety in the Secondary Sector

2.2. Linkage of Occupational Health and Safety and Corporate Performance

2.3. Review of Occupational Health and Safety in Case Study Area

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3. Reliability and Validity Testing

- Health & Safety Logbook Compliance—Whether the company maintains an officially certified Health & Safety Logbook.

- Written Occupational Risk Assessment—Whether the company has a formalized risk assessment document.

- Emergency Response Plan—Whether the company has an emergency preparedness strategy.

- OHS Certification (ISO 45001/OHSAS 18001)—Whether the company implements an internationally recognized occupational safety management system.

4. Results

4.1. Survey Analysis Key Results

4.2. Reliability and Validity Tests Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Safety and Health at the Heart of the Future of Work: Building on 100 Years of Experience; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.ilo.org (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Christian, M.; Bradley-Geist, J.; Wallace, C.; Burke, M. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriou, D.; Papakostas, K. Review of management comprehensiveness on occupational health and safety for PPP transportation projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateeq, A.; Al-refaei, A.A.-A.; Alzoraiki, M.; Milhem, M.; Al-Tahitah, A.N.; Ibrahim, A. Sustaining organizational outcomes in manufacturing firms: The role of Hrm and occupational health and safety. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 89/391/EEC—Framework Directive on Occupational Safety and Health. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63787.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Ji, Z.; Pons, D.; Su, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Pearse, J. Integrating occupational health and safety risk and production economics for sustainable SME growth. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe, H.; Heenatigala, S. Insights from the field: A comprehensive analysis of industrial accidents in plants and strategies for enhanced workplace safety. Open J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maysoon Shafeeq, A.A. Review of previous literature of occupational safety and health (OSH) factors affecting employees performance. Am. Based Res. J. 2018, 7, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, P.; Takala, J.; Saarela, K. Global estimates of occupational accidents. Saf. Sci. 2006, 44, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, S.R.; Kota, S.; Jasti, N.V.K.; Soni, G.; Prakash, S. An occupational health and safety management system framework for lean process industries: An interpretive structural modelling approach. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2022, 13, 1367–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, D.; Reineholm, C.; Ståhl, C.; Hellgren, M. Occupational health and safety management: Managers’ organizational conditions and effect on employee well-being. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2024, 17, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D.; Sartzetaki, M.; Karagkouni, A. Airport landside area planning: An activity-based methodology for seasonal airports. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 82, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartzetaki, M.; Dimitriou, D.; Karagkouni, A. Assortment of the regional business ecosystem effects driven by new motorway projects. In Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 82, pp. 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.; Nichols, T. Worker Representation and Workplace Health and Safety; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Annual Industrial Report; Hellenic Statistical Authority: Athens, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, D.; Zantanidis, S. Key Aspects of Occupational Health and Safety Towards Efficiency and Performance in Air Traffic Management; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2021; pp. 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Health and Safety at Work in Greece; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Worker Participation in the Management of Occupational Safety and Health: Qualitative Evidence from ESENER-2; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2017; Available online: https://osha.europa.eu (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Gunningham, N. Integrating management systems and occupational health and safety regulation. J. Law Soc. 2002, 26, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; ανδ Rowlinson, S. Occupational Health and Safety in Construction Project Manag; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzini, M.; Kim, W.; Ajoudani, A. An online multi-index approach to human ergonomics assessment in the workplace. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2022, 55, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanko, M.; Dawson, P. Occupational health and safety management in organizations: A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubykh, Z.; Turner, N.; Hershcovis, S.; Deng, C. A meta-analysis of leadership and workplace safety: Examining relative importance, contextual contingencies, and methodological moderators. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinodkumar, M.N.; Bhasi, M. Safety management practices and safety behaviour: Assessing the mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, P.W.; Dul, J. Human factors: Spanning the gap between OM and HRM. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2010, 30, 923–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick, J.; Presser, S. and Building, Art-Sociology. Question and Questionnaire Design. In Handbook of Survey Research; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, R.A.; Straits, B.C. Approaches to Social Research, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, D.; Sartzetaki, M.; Karagkouni, A. Managing Airport Corporate Performance: Leveraging Business Intelligence and Sustainable Transition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; ISBN 978-0-443-29109-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartzetaki, M.; Karagkouni, A.; Dimitriou, D. A conceptual framework for developing intelligent services (a platform) for transport enterprises: The designation of key drivers for action. Electronics 2023, 12, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Question | Response Format |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Demographic and Professional Information | Gender | Female, Male, Other |

| Age | 20–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, >60 | |

| Education background | Technical University, University, MSc/MBA, PhD | |

| Industry sector of the company | Open-ended | |

| Number of employees in the company | 1–20 (Micro), 21–50 (Small), 51–100 (Medium), 101–250 (Medium), 251–500 (Large), >500 (Large) | |

| Role in the company | Owner/Board Member, CEO/Managing Director, General Manager, Director of OHS, Production Manager, Department Supervisor, Health and Safety Officer, Other | |

| Number of years in the company | 0–5, 6–10, 11–20, >20 | |

| Number of employees under responsibility | 1–10, 11–20, 21–50, 51–100, >100 | |

| 2. OHS Compliance with Legal Obligations | Does the company employ a safety technician? | Yes/No |

| Does the company employ an occupational health doctor? | Yes/No | |

| Does the company maintain a legally certified health and safety logbook? | Yes/No | |

| Does the company have a written occupational risk assessment? | Yes/No | |

| Does the company have an emergency response plan? | Yes/No | |

| Does the company implement an occupational health and safety management system (OHSAS 18001/ISO 45001) [6]? | Yes/No | |

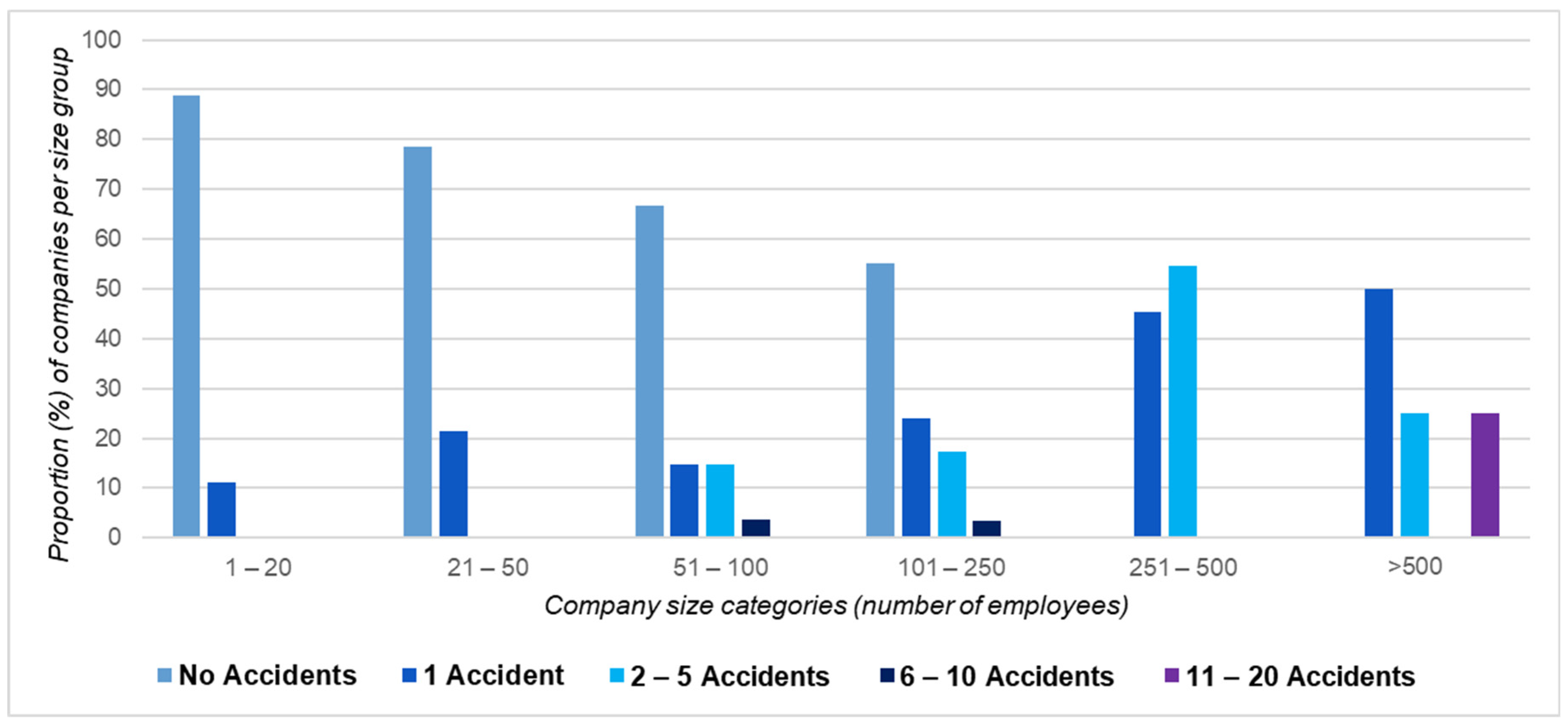

| 3. Lagging Indicators—Workplace Safety Performance | Have there been any workplace accidents in the past year? | Yes/No |

| If yes, how many? | No Accidents, 1 Accident, 2–5 Accidents, 6–10 Accidents, 11–20 Accidents | |

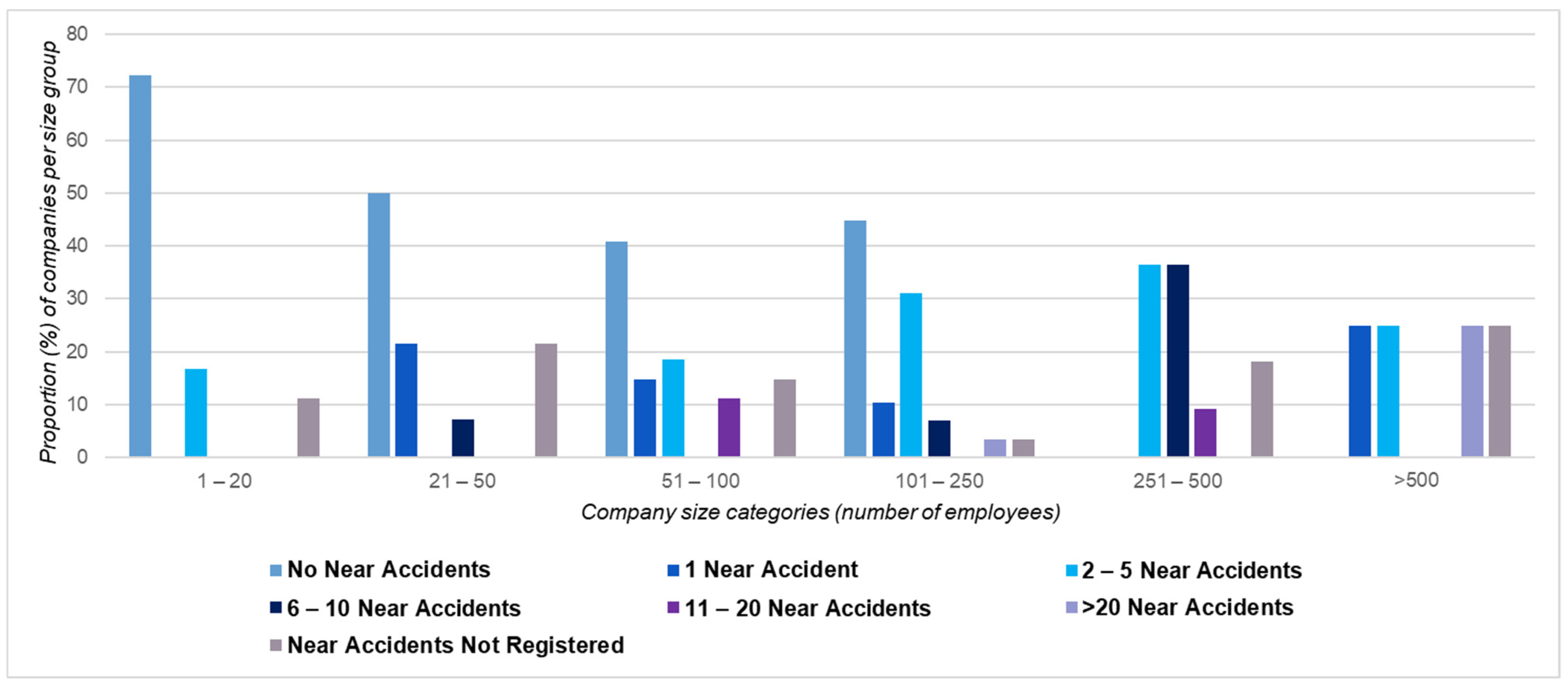

| Have there been any near-miss incidents in the past year? | Yes/No | |

| If yes, how many? | No Incidents, 1 Incident, 2–5 Incidents, 6–10 Incidents, 11–20 Incidents | |

| 4a. Workplace Inspections and Audits | Are workplace inspections conducted by the health and safety officer? | Never, Rarely (1–2 times/year), Occasionally (2–3 times/year), Often (once a month), Always (every week) |

| Does the health and safety officer record recommendations in the health and safety logbook? | Never, Rarely, Occasionally, Often, Always | |

| Are inspections conducted by a competent person within the company? | Never, Rarely, Occasionally, Often, Always | |

| Are measurements of harmful workplace factors conducted? | Never, Rarely, Occasionally, Often, Always | |

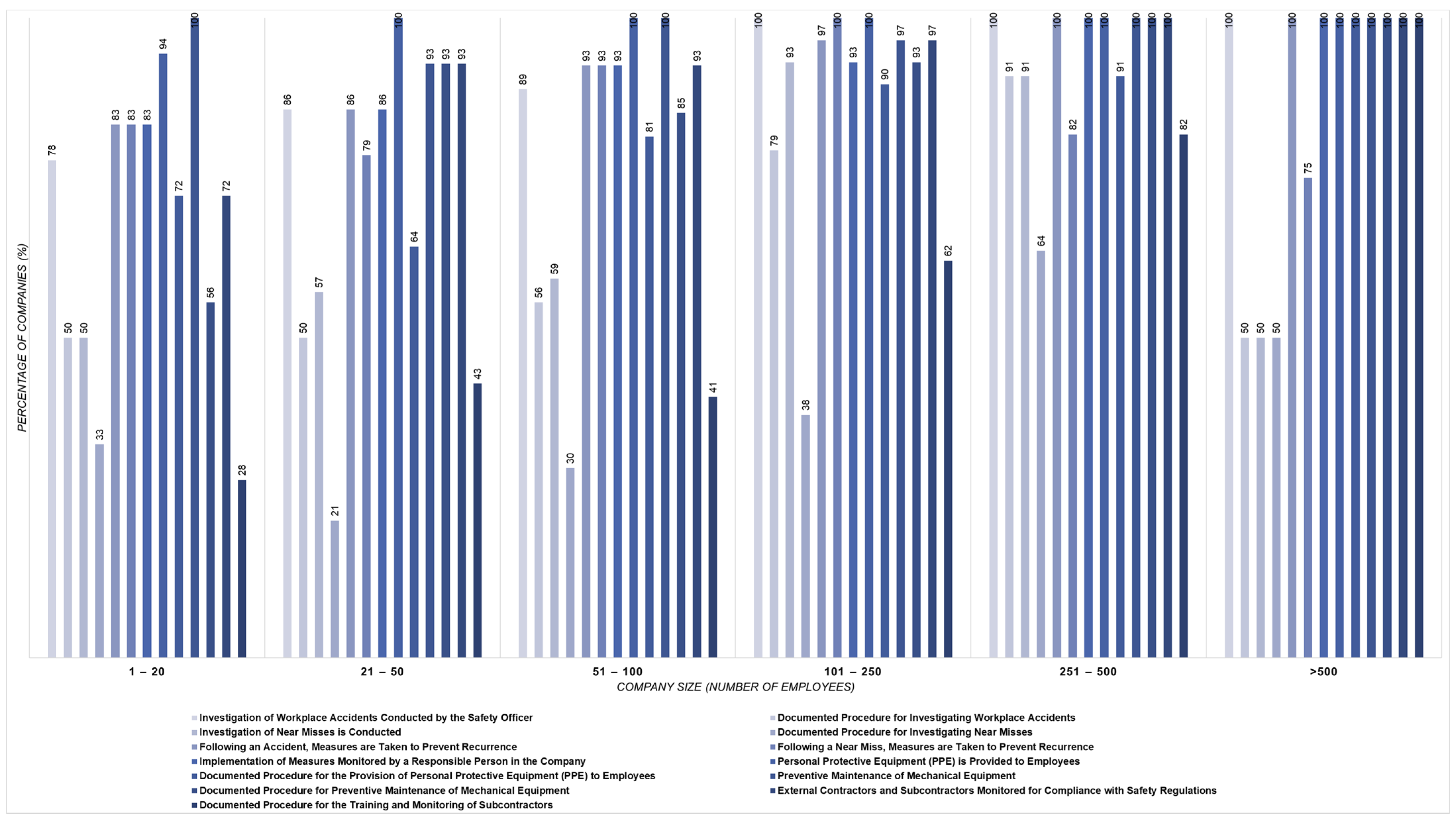

| 4b. Preventive Actions | Are workplace accidents investigated by the safety officer? | Yes/No |

| Is there a documented procedure for investigating workplace accidents? | Yes/No | |

| Are near-miss incidents investigated? | Yes/No | |

| Is there a documented procedure for investigating near-miss incidents? | Yes/No | |

| Following an accident, are measures taken to prevent recurrence? | Yes/No | |

| Following a near-miss incident, are measures taken to prevent recurrence? | Yes/No | |

| Is the implementation of these measures monitored by a responsible person? | Yes/No | |

| Is personal protective equipment (PPE) provided to employees? | Yes/No | |

| Is there a documented procedure for the provision of PPE? | Yes/No | |

| Is preventive maintenance carried out on mechanical equipment? | Yes/No | |

| Is there a documented procedure for preventive maintenance? | Yes/No | |

| Are external contractors and subcontractors monitored for compliance? | Yes/No | |

| Is there a documented procedure for training and monitoring subcontractors? | Yes/No |

| Variables | Descriptive Statistics n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20–30 | 5 (5) |

| 31–40 | 28 (27) |

| 41–50 | 35 (34) |

| 51–60 | 34 (33) |

| >60 | 1 (1) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 67 (65) |

| Male | 36 (35) |

| Education Background | |

| Technical University | 22 (21) |

| University | 34 (33) |

| MSc/MBA | 44 (43) |

| PhD | 3 (3) |

| Role in the Company | |

| Owner/Board Member | 24 (23) |

| CEO/Managing Director | 8 (8) |

| General Manager | 11 (11) |

| Director of Occupational Health and Safety Department | 9 (9) |

| Production Manager | 13 (13) |

| Department Supervisor | 12 (12) |

| Health and Safety Officer | 15 (15) |

| Other | 11 (11) |

| Number of Years in the Company | |

| 0–5 | 31 (30) |

| 6–10 | 23 (22) |

| 11–20 | 27 (26) |

| >20 | 22 (21) |

| Number of Employees Under Responsibility | |

| 1–10 | 41 (40) |

| 11–20 | 10 (10) |

| 21–50 | 21 (21) |

| 51–100 | 18 (18) |

| >100 | 12 (12) |

| Number of Employees in the Company | |

| 1–20 (micro-enterprises) | 18 (17) |

| 21–50 (small enterprises) | 14 (14) |

| 51–100 (medium enterprises) | 27 (26) |

| 101–250 (medium enterprises) | 29 (28) |

| 251–500 (large enterprises) | 11 (11) |

| >500 (large enterprises) | 4 (4) |

| Risk Level | Industry Type | Key Occupational Hazards | Common OHS Measures Implemented |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Chemical Manufacturing | Exposure to hazardous chemicals, fire/explosion risks, toxic gas leaks | Hazard control systems, emergency response plans, safety audits |

| Metal Production and Fabrication | Heavy machinery, high temperatures, metal fumes, ergonomic strain | PPE use, ventilation systems, automated safety monitoring | |

| Energy Production | Flammable substances, high-pressure systems, confined space risks | Process safety management, real-time hazard detection, advanced fire suppression | |

| Moderate | Food and Beverage Manufacturing | Machine-related injuries, food contamination risks, ergonomic strain | Sanitation protocols, machine safety training, PPE |

| Printing and Packaging | Repetitive strain injuries, exposure to chemical fumes | Ergonomic workstations, protective gloves, proper ventilation | |

| Automotive and Equipment Manufacturing | Mechanical hazards, exposure to lubricants and fumes | Protective barriers, frequent safety drills, machine maintenance | |

| Low | Textile and Apparel | Needle injuries, repetitive motion, minor fire hazards | Fire safety measures, ergonomic assessments, manual handling training |

| Retail and Distribution | Logistics-related injuries, material handling risks | Forklift safety training, PPE for handling goods, periodic risk assessments |

| Never | Rarely (1–2 Times/Year) | Occasionally (2–3 Times/Year) | Often (Once a Month) | Always (Every Week) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inspections by the Health and Safety Officer | |||||

| 1–20 | 0 | 6 | 17 | 78 | 0 |

| 21–50 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 71 | 21 |

| 51–100 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 74 | 15 |

| 101–250 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 31 | 66 |

| 250–500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 82 |

| >500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 |

| Recommendations by the Health and Safety Officer in the Logbook | |||||

| 1–20 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 72 | 0 |

| 21–50 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 71 | 21 |

| 51–100 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 59 | 15 |

| 101–250 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 41 | 31 |

| 250–500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 55 |

| >500 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 50 | 25 |

| Inspections by a Competent Person | |||||

| 1–20 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 50 | 28 |

| 21–50 | 0 | 14 | 7 | 43 | 36 |

| 51–100 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 56 | 22 |

| 101–250 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 59 | 38 |

| 250–500 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 36 | 55 |

| >500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Measurements of Harmful Factors | |||||

| 1–20 | 50 | 17 | 0 | 28 | 6 |

| 21–50 | 21 | 36 | 14 | 21 | 7 |

| 51–100 | 4 | 41 | 37 | 11 | 7 |

| 101–250 | 0 | 41 | 31 | 10 | 17 |

| 250–500 | 0 | 55 | 18 | 27 | 0 |

| >500 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Distribution of Workplace Accidents Based on the Implementation of | No Accident | 1 Accident | 2–5 Accidents | 6–10 Accidents | 11–20 Accidents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health and Safety Officer | |||||

| Yes | 59 | 22 | 16 | 2 | 1 |

| No | 50 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Occupational Doctor | |||||

| Yes | 49 | 25 | 21 | 3 | 1 |

| No | 86 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Authorized Logbook | |||||

| Yes | 62 | 19 | 16 | 2 | 1 |

| No | 67 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Written Occupational Risk Assessment | |||||

| Yes | 58 | 22 | 17 | 2 | 1 |

| No | 73 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Emergency Plan | |||||

| Yes | 58 | 21 | 18 | 2 | 1 |

| No | 69 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| OHSAS 18001/ISO 45001 | |||||

| Yes | 53 | 24 | 18 | 2 | 2 |

| No | 64 | 21 | 14 | 2 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mixafenti, S.; Moutzouri, A.; Karagkouni, A.; Sartzetaki, M.; Dimitriou, D. Assessment of Occupational Health and Safety Management: Implications for Corporate Performance in the Secondary Sector. Safety 2025, 11, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020044

Mixafenti S, Moutzouri A, Karagkouni A, Sartzetaki M, Dimitriou D. Assessment of Occupational Health and Safety Management: Implications for Corporate Performance in the Secondary Sector. Safety. 2025; 11(2):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMixafenti, Stavroula (Vivi), Antonia Moutzouri, Aristi Karagkouni, Maria Sartzetaki, and Dimitrios Dimitriou. 2025. "Assessment of Occupational Health and Safety Management: Implications for Corporate Performance in the Secondary Sector" Safety 11, no. 2: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020044

APA StyleMixafenti, S., Moutzouri, A., Karagkouni, A., Sartzetaki, M., & Dimitriou, D. (2025). Assessment of Occupational Health and Safety Management: Implications for Corporate Performance in the Secondary Sector. Safety, 11(2), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020044