First-Principles Calculation Study on the Interfacial Stability Between Zr and F Co-Doped Li6PS5Cl and Lithium Metal Anode

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methodology and Structure Models

2.1. Computational Methodology

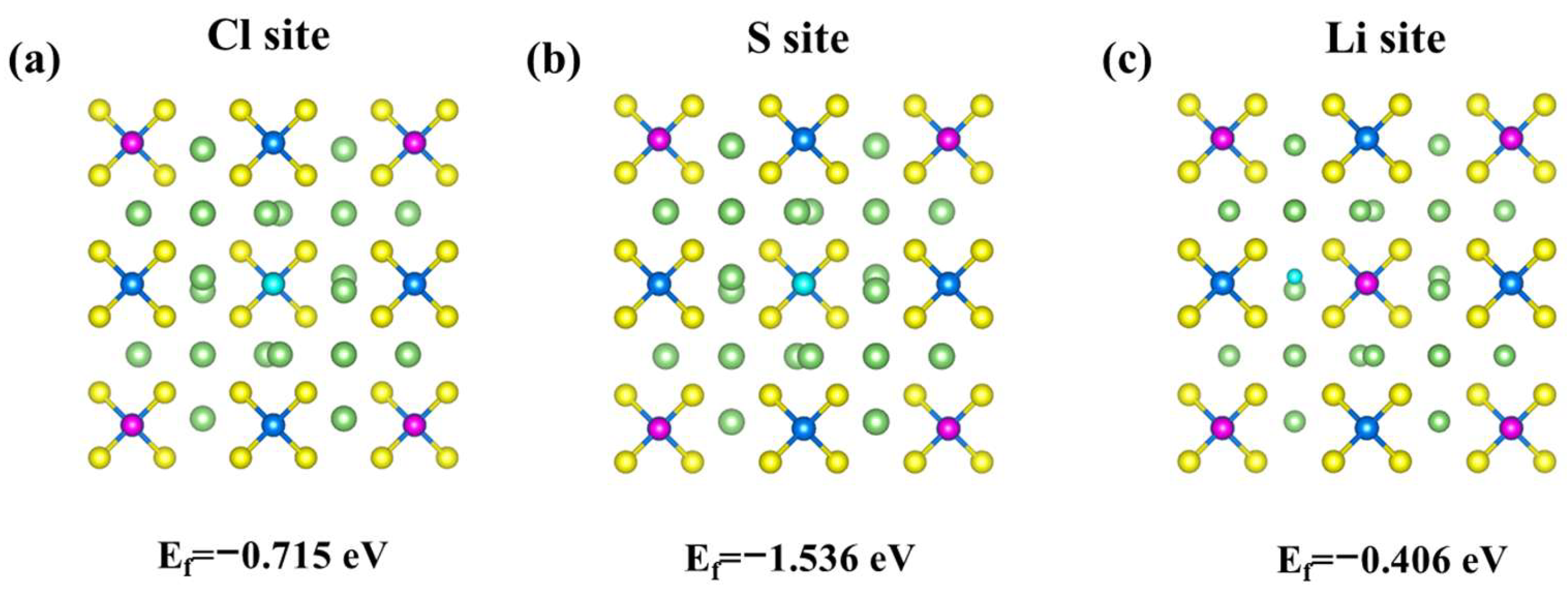

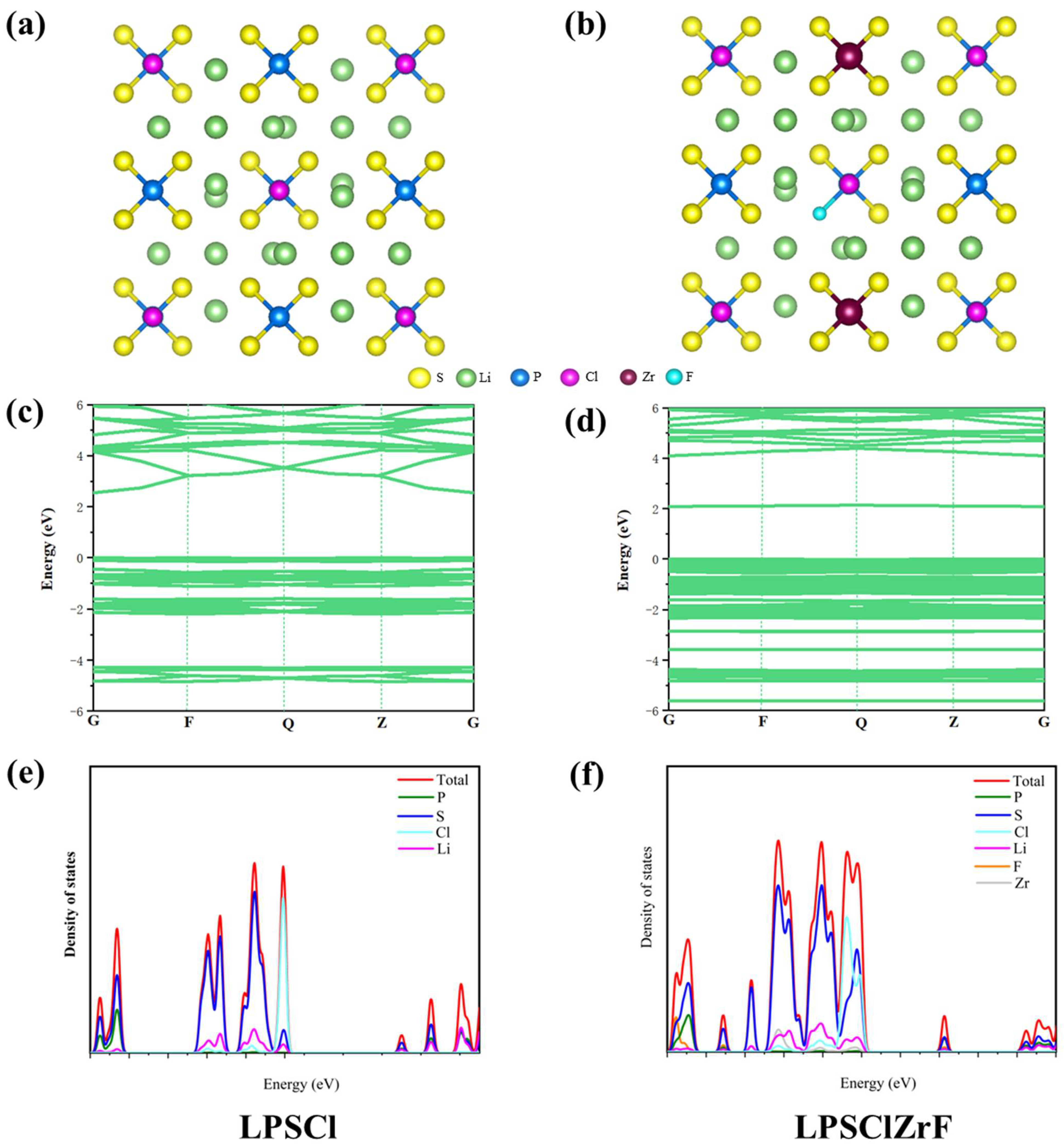

2.2. Structure Model and Properties of LPSClZrF

2.3. Interface Structure Models

3. Results and Discussion

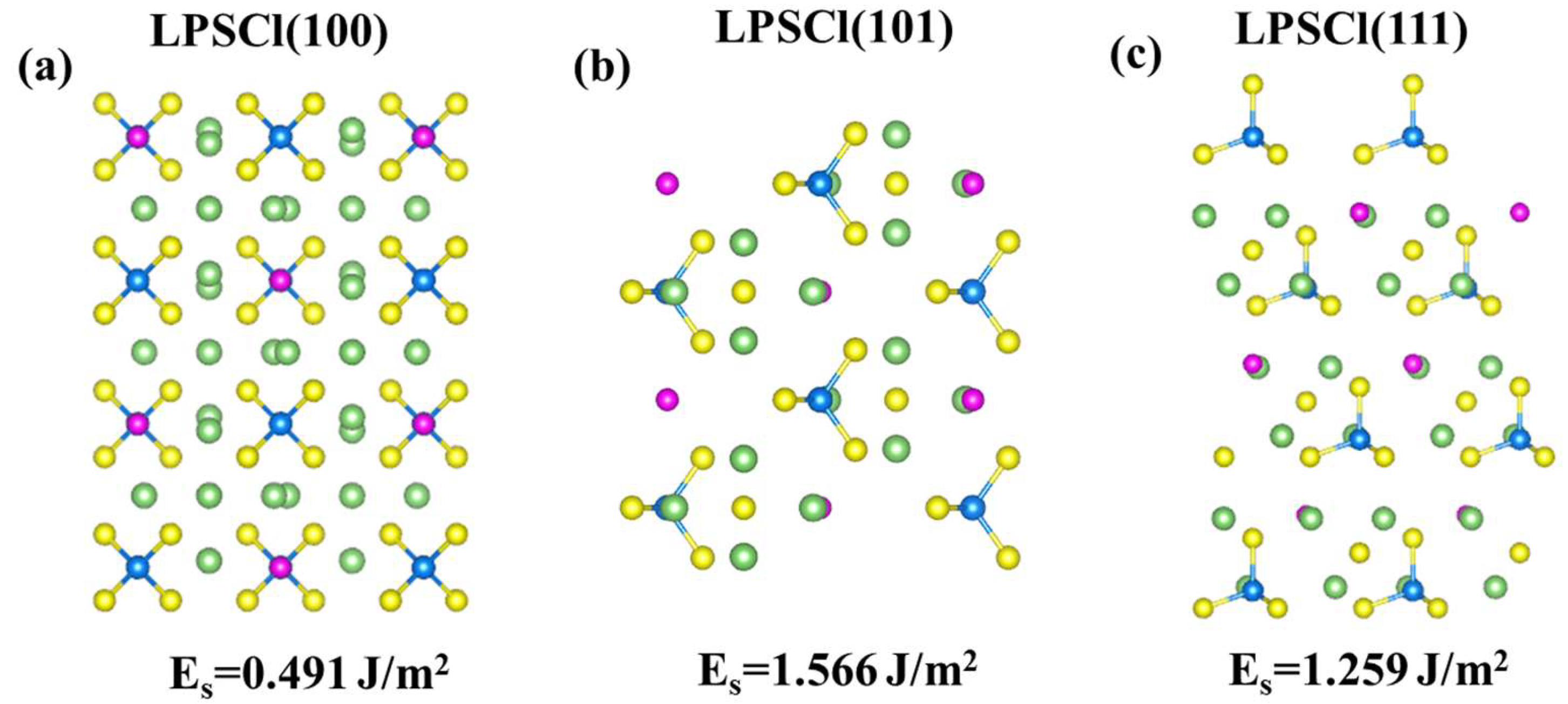

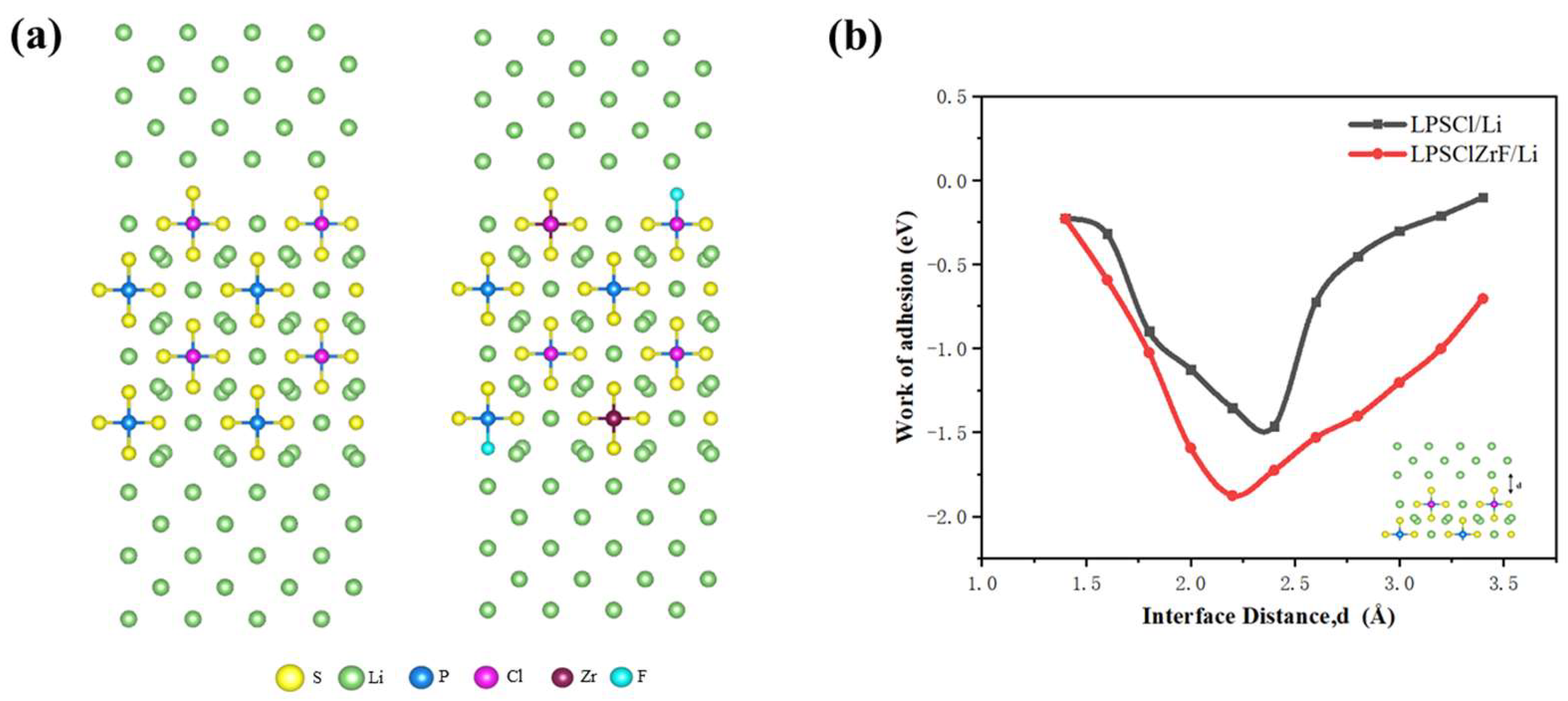

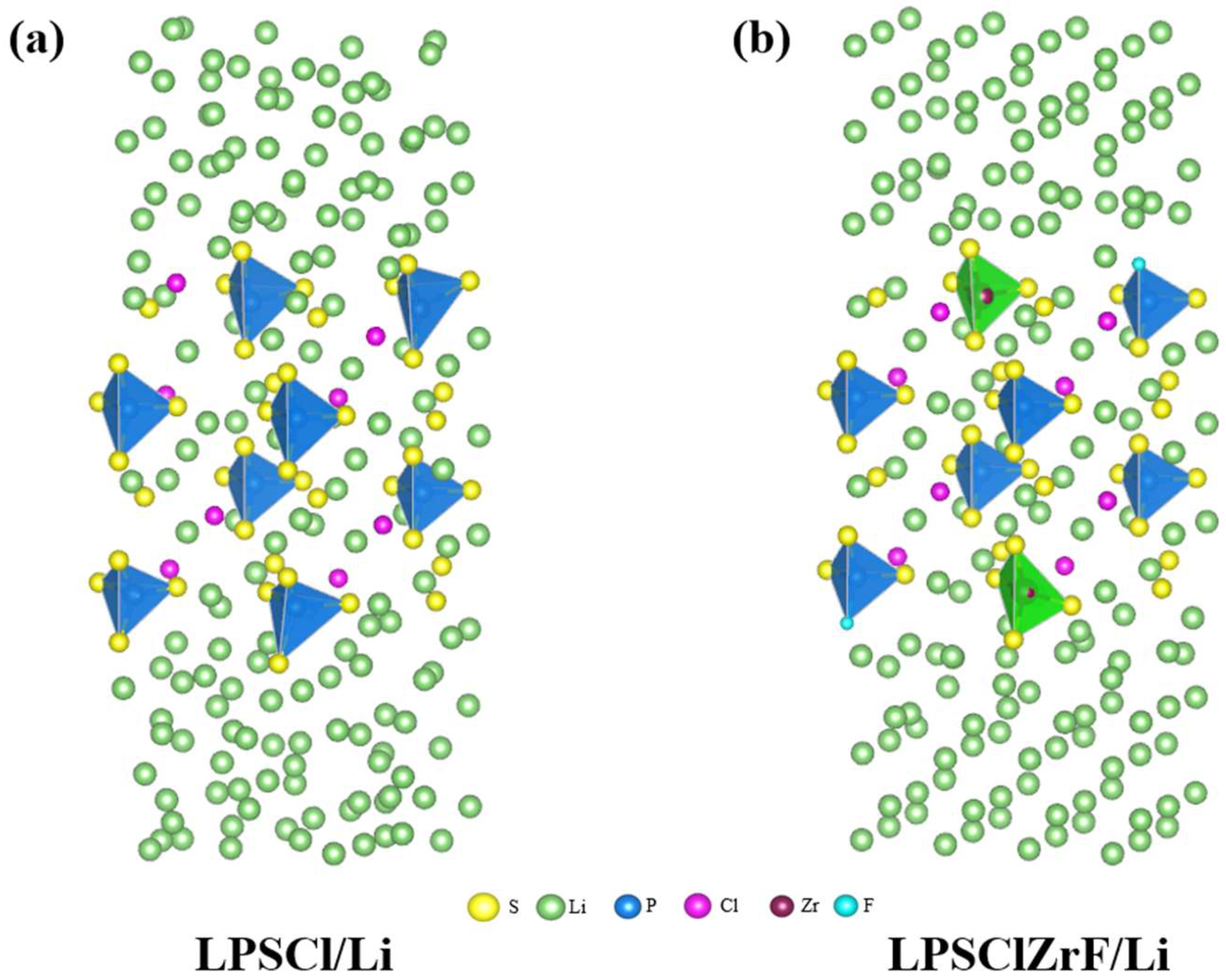

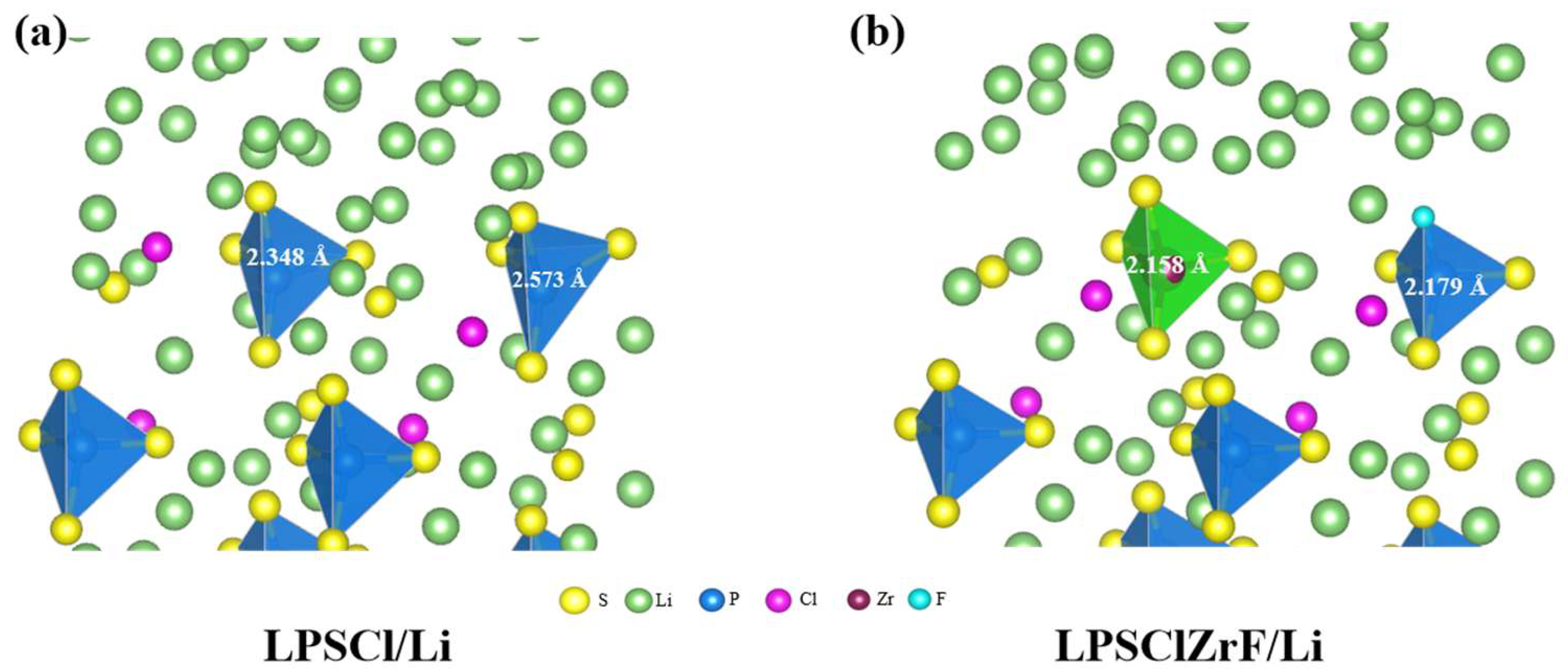

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Interfacial Deformation

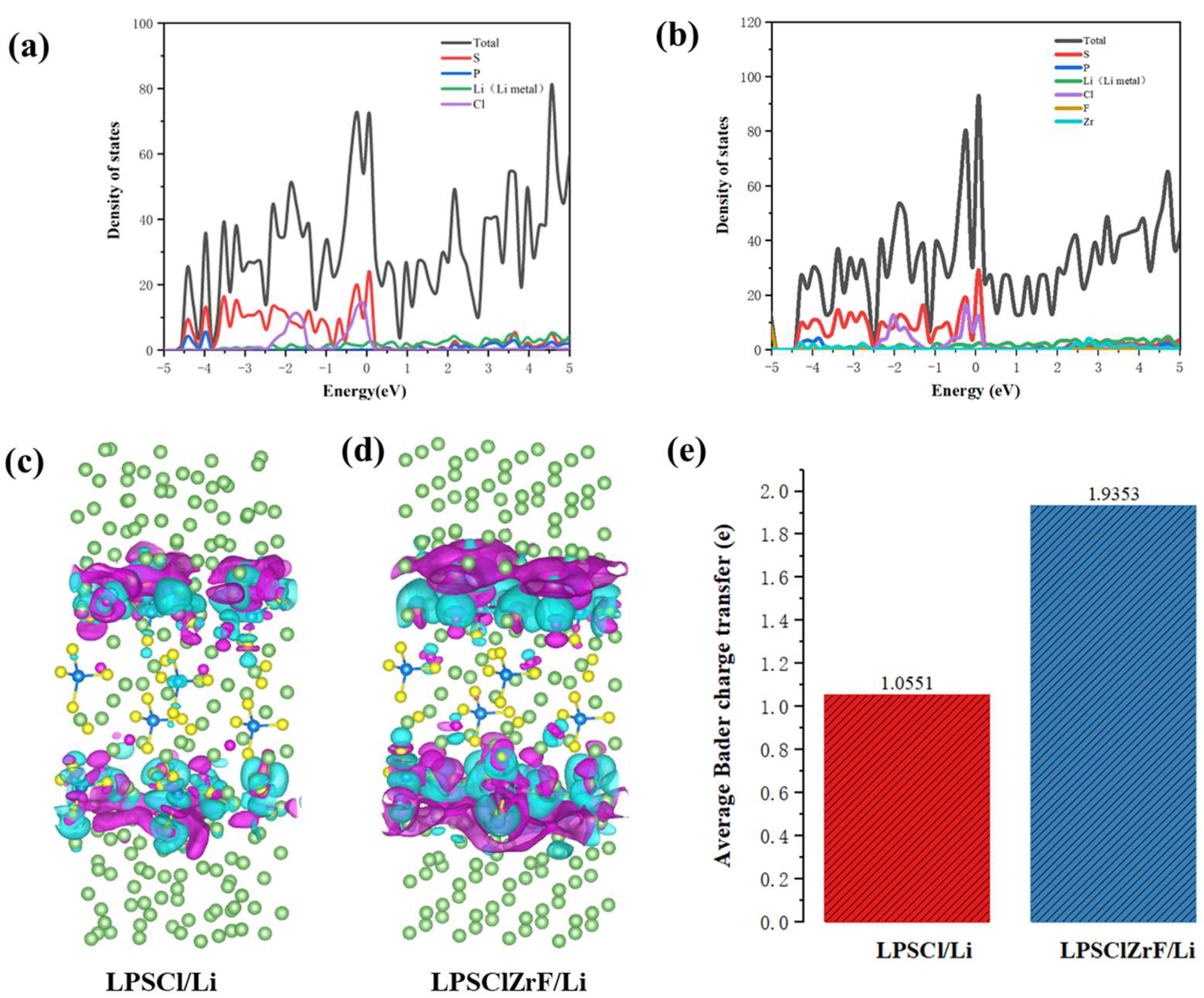

3.2. Electronic Structure

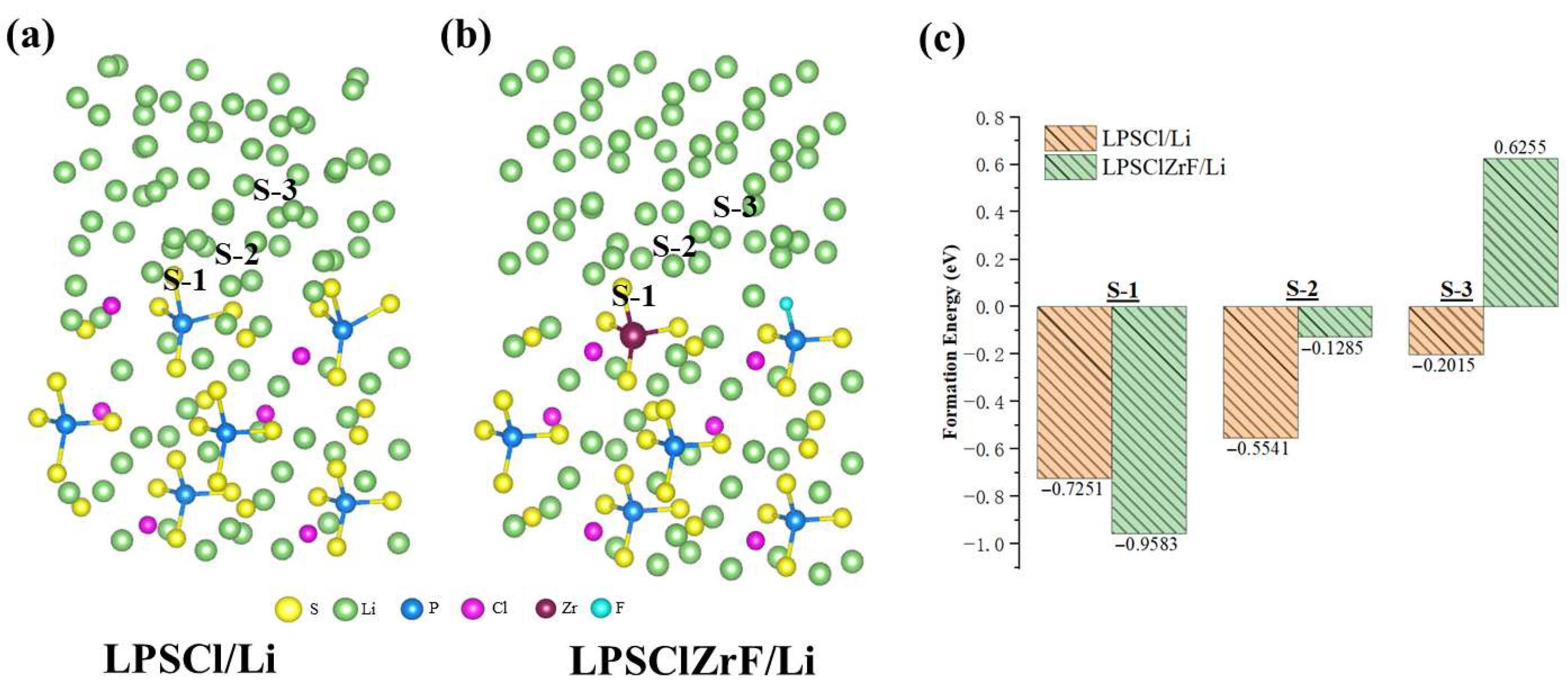

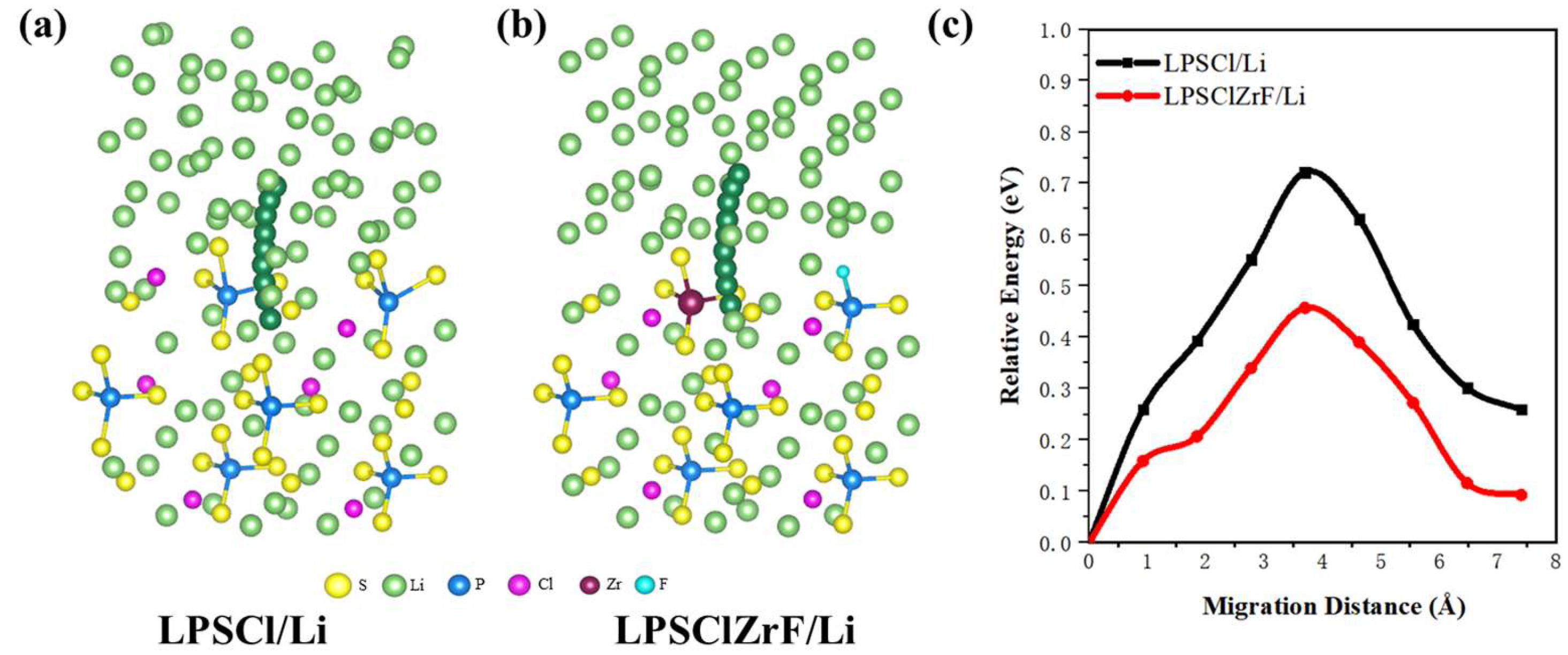

3.3. Lithium-Ion Migration at the Interface

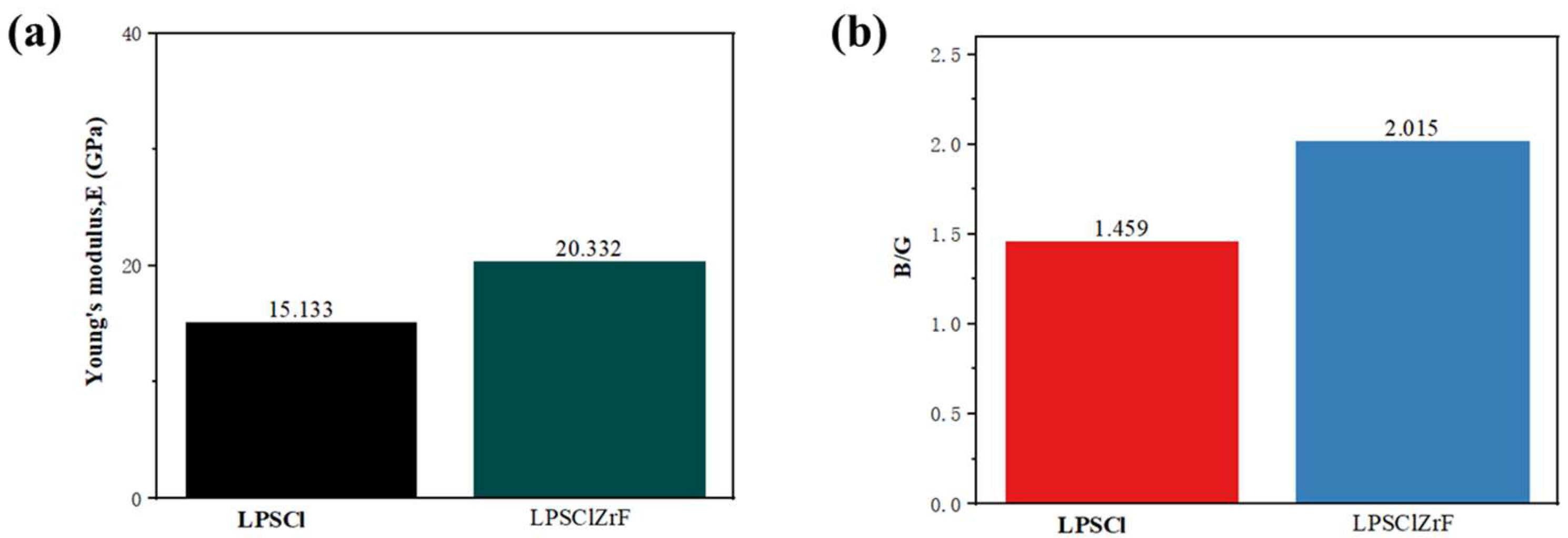

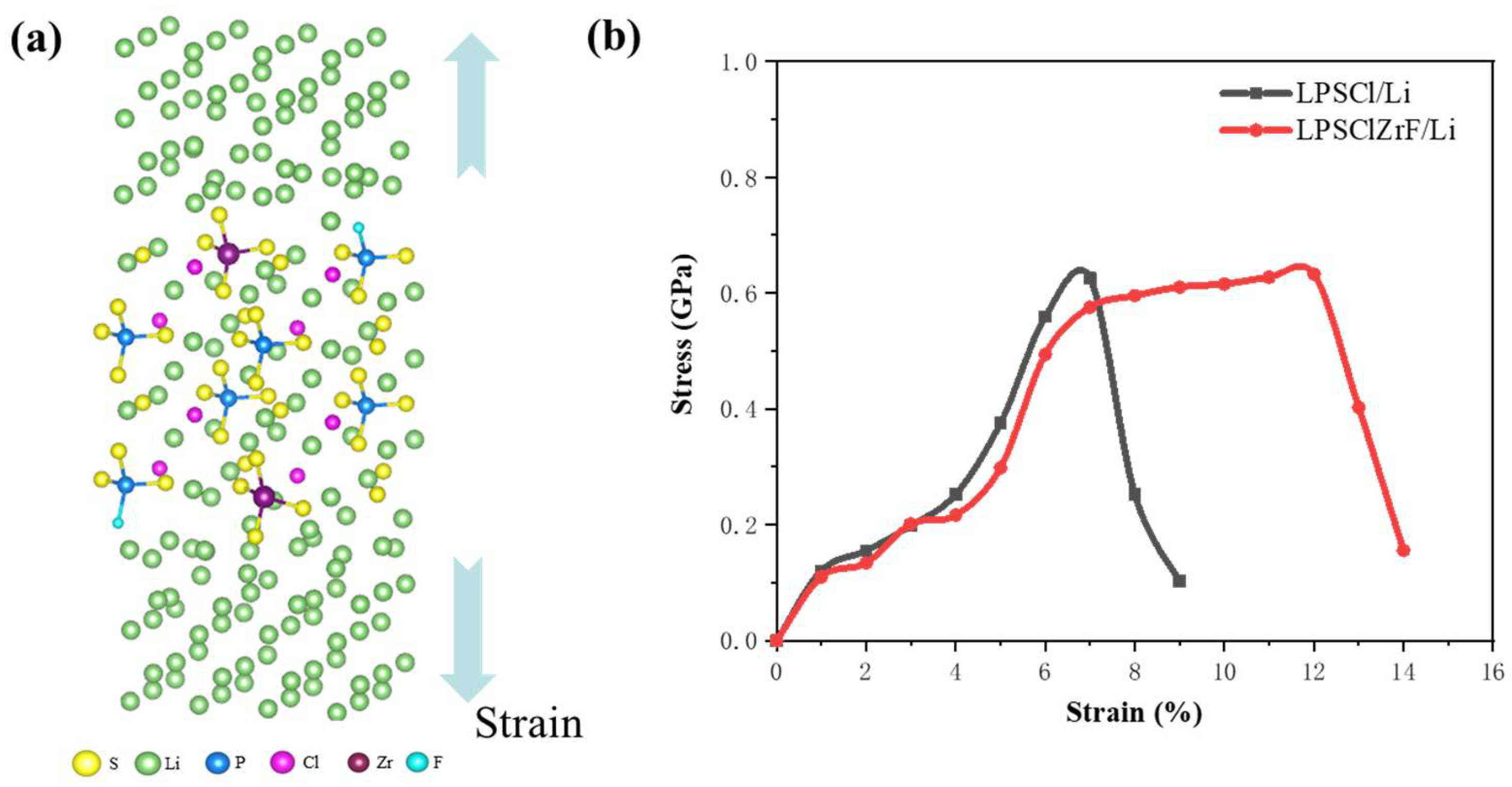

3.4. Stress–Strain Analysis of Interface Structures

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merrill, L.C. Resting restores performance of discharged lithium-metal batteries. Nature 2024, 626, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.D.; Zhu, Y.H.; Feng, Y.; Han, Y.H.; Gu, Z.Y.; Liu, R.X.; Yang, D.Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Sun, W.; et al. Research Progress on Key Materials and Technologies for Secondary Batteries. ACTA Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2022, 38, 2208008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Guo, S.H.; Zhou, H.S. Solar energy storage in the rechargeable batteries. NanoToday 2017, 16, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.X.; Jiang, T.L.; Ali, M.; Meng, Y.H.; Jin, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, W. Rechargeable Batteries for Grid Scale Energy Storage. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 16610–16751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Gong, X. Electrochemical Energy Storage Devices-Batteries, Supercapacitors, and Battery-Supercapacitor Hybrid Devices. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2025, 7, 2233–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.X.; Wang, L.Y.; Kan, C.D.; Yang, C. Thermal-Electrical-Mechanical Coupled Finite Element Models for Battery Electric Vehicle. Machines 2024, 12, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Abbas, Q.; Shinde, P.A.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Rechargeable batteries: Technological advancement, challenges, current and emerging applications. Energy 2023, 266, 126408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, H.J.; Chang, X.; Zhao, Y.M.; Meng, Q.H.; Xu, P.; Zhao, C.Z.; Chen, J.H.; et al. Roadmap for rechargeable batteries: Present and beyond. Sci. China-Chem. 2024, 67, 13–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Kim, J.T.; Wang, C.S.; Sun, X.L. Progress and Prospects of Inorganic Solid-State Electrolyte-Based All-Solid-State Pouch Cells. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2209074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, H.; Liu, H.; Zhao, C.Z.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, X.B.; Huang, J.Q.; Zhang, Q. Unlocking the Failure Mechanism of Solid State Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.F.; Guan, Z.Q.; Chu, F.L.; Xue, Z.C.; Wu, F.X.; Yu, Y. Air-stable inorganic solid-state electrolytes for high energy density lithium batteries: Challenges, strategies, and prospects. Infomat 2022, 4, e12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersak, T.A.; Malabet, H.J.G.; Yadav, V.; Pieczonka, N.P.W.; Collin, W.; Cai, M. Flammability of sulfide solid-state electrolytes β-Li3PS4 and Li6PS5Cl: Volatilization and autoignition of sulfur vapor-New insight into all-solid-state battery thermal runaway. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 102, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, S.; Wu, X.L.; Wang, J.T.; Li, X.; Hao, X.F.; Meng, Y.Z. Research Progress on Solid-State Electrolytes in Solid-State Lithium Batteries: Classification, Ionic Conductive Mechanism, Interfacial Challenges. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Choi, W.; Hwang, S.J.; Kim, D.W. Incorporation of Ionic Conductive Polymers into Sulfide Electrolyte-Based Solid-State Batteries to Enhance Electrochemical Stability and Cycle Life. Energy Environ. Mater. 2024, 7, e12776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.K.; Yu, T.; Guo, S.H.; Zhou, H.S. Designing High-Performance Sulfide-Based All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries: From Laboratory to Practical Application. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2023, 39, 2301027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaya, N.; Homma, K.; Yamakawa, Y.; Hirayama, M.; Kanno, R.; Yonemura, M.; Kamiyama, T.; Kato, Y.; Hama, S.; Kawamoto, K.; et al. A lithium superionic conductor. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.M.; He, Q.S.; Liu, G.Z.; Gu, Z.; Wu, M.; Sun, T.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Huang, L.F.; Yao, X.Y. Fluorinated Li10GeP2S12 Enables Stable All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2211047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seino, Y.; Ota, T.; Takada, K.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M. A sulphide lithium super ion conductor is superior to liquid ion conductors for use in rechargeable batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayavarapu, P.R.; Sharma, N.; Peterson, V.K.; Adams, S. Variation in structure and Li+-ion migration in argyrodite-type Li6PS5X (X = Cl, Br, I) solid electrolytes. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 1807–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.T.; Xiang, Y.X.; Wang, K.J.; Zhu, J.P.; Jin, Y.T.; Wang, H.C.; Zheng, B.Z.; Chen, Z.R.; Tao, M.M.; Liu, X.S.; et al. Understanding the failure process of sulfide-based all-solid-state lithium batteries via operando nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C.; Hong, J.J.; Sebti, E.; Zhou, K.; Wang, S.; Feng, S.J.; Pennebaker, T.; Hui, Z.Y.; Miao, Q.S.; Lu, E.R.; et al. Surface molecular engineering to enable processing of sulfide solid electrolytes in humid ambient air. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.X.; Gupta, M.K.; Rosenbach, C.; Lin, H.M.; Osti, N.C.; Abernathy, D.L.; Zeier, W.G.; Delaire, O. Liquid-like dynamics in a solid-state lithium electrolyte. Nat. Phys. 2025, 21, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Jun, S.; Song, Y.B.; Baeck, K.H.; Bae, H.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y.S. Rationally Designed Conversion-Type Lithium Metal Protective Layer for All-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2303762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yang, J.; Nuli, Y.N.; Wang, J.L. Realizing the dendrite-free sulfide-based all-solid-state Li metal battery by surface design. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 69, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; He, X.; Wang, C. Interface design for all-solid-state lithium batteries. Nature 2023, 623, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golov, A.; Carrasco, J. Molecular-Level Insight into the Interfacial Reactivity and Ionic Conductivity of a Li-Argyrodite Li6PS5Cl Solid Electrolyte at Bare and Coated Li-Metal Anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 43734–43745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, K.; Kaliyaperumal, C.; Uthayakumar, A.; Yoon, I.; Lee, G.H.Y.; Shin, D. Enhancing the Moisture Stability and Electrochemical Performances of Li6PS5Cl Solid Electrolytes through Ga Substitution. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 441, 141757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, S.; Sedlmaier, S.J.; Dietrich, C.; Zeier, W.G.; Janek, J. Interfacial reactivity and interphase growth of argyrodite solid electrolytes at lithium metal electrodes. Solid State Ion. 2018, 318, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.F.; Yang, L.; Luo, K.L.; Liu, L.; Tao, X.Y.; Yi, L.G.; Liu, X.H.; Luo, Z.G.; Wang, X.Y. Performance Improvement of Li6PS5Cl Solid Electrolyte Modified by Poly(ethylene oxide)-Based Composite Polymer Electrolyte with ZSM-5 Molecular Sieves. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 2356–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.Y.; Yang, M.L.; Xie, W.R.; Tian, F.L.; Liu, G.Z.; Cui, P.; Wu, T.; Yao, X.Y. Micro-Sized MoS6@15%Li7P3S11 Composite Enables Stable All-Solid-State Battery with High Capacity. Batteries 2023, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yao, L.; Chen, X.D.; Jin, J.; Wu, M.F.; Wang, Q.; Zha, W.P.; Wen, Z.Y. Double-Faced Bond Coupling to Induce an Ultrastable Lithium/Li6PS5Cl Interface for High-Performance All-Solid-State Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 11950–11961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Xia, J.L.; Ji, X.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhang, J.X.; He, X.Z.; Zhang, W.R.; Wan, H.L.; Wang, C.S. Lithium anode interlayer design for all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Yan, C.; Gao, M.; Du, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Gan, J.; Wu, Z.; Sun, W.; Jiang, Y.; et al. New Insights into the Effects of Zr Substitution and Carbon Additive on Li3-xEr1-xZrxCl6 Halide Solid Electrolytes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 8095–8105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, C.; Yang, L.; Luo, K.; Liu, L.; Tao, X.; Yi, L.; Liu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, X. Ionic conductivity and interfacial stability of Li6PS5Cl–Li6.5La3Zr1.5Ta0.5O12 composite electrolyte. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2021, 25, 2513–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, W.; Shreyas, V.; Li, Y.; Koralalage, M.K.; Jasinski, J.B.; Thapa, A.; Sumanasekera, G.; Ngo, A.T.; Narayanan, B.; Wang, H. Synthesis of Fluorine-Doped Lithium Argyrodite Solid Electrolytes for Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 11483–11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Yao, J.M.; Ye, Z.R.; Lin, Q.Q.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Li, S.L.; Song, D.W.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, L. Al-F co-doping towards enhanced electrolyte-electrodes interface properties for halide and sulfide solid electrolytes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.B.; Xu, C.Q.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.Q. Insights into interfacial stability of Li6PS5Cl solid electrolytes with buffer layers. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2019, 19, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, G.; Li, H.; Ju, J.; Gu, J.; Xu, R.; Jin, S.; Zhou, J.; Chen, B. Novel Zr-doped β-Li3PS4 solid electrolyte for all-solid-state lithium batteries with a combined experimental and computational approach. Nano Res. 2022, 16, 3516–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsif, M.; Shah, M.; Ullah, Z.; Ashraf, M.W.; Fayaz, M.; Alsalmah, H.A.; Murtaza, G. First principles study of the structural, mechanical and optical properties of Li6PS5X (X= Cl, I) argyrodite compounds. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2023, 661, 414932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, S.F. XCII. Relations between the Elastic Moduli and the Plastic Properties of Polycrystalline Pure Metals. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1954, 45, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chu, I.-H.; Luo, J.; Ong, S.P. Elastic Properties of Alkali Superionic Conductor Electrolytes from First Principles Calculations. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 163, A67–A74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Merinov, B.V.; Morozov, S.; Goddard, W.A. Quantum Mechanics Reactive Dynamics Study of Solid Li-Electrode/Li6PS5Cl-Electrolyte Interface. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1454–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Ji, Y.; Qian, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Bao, T.; Chen, P.; Mei, J. First-Principles Calculation Study on the Interfacial Stability Between Zr and F Co-Doped Li6PS5Cl and Lithium Metal Anode. Batteries 2025, 11, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120456

Zhang J, Zhang H, Chen B, Ji Y, Qian C, Wang J, Wang Y, Bao T, Chen P, Mei J. First-Principles Calculation Study on the Interfacial Stability Between Zr and F Co-Doped Li6PS5Cl and Lithium Metal Anode. Batteries. 2025; 11(12):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120456

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Junbo, Hailong Zhang, Binbin Chen, Yinlian Ji, Caixia Qian, Jue Wang, Yu Wang, Tiantian Bao, Peipei Chen, and Jie Mei. 2025. "First-Principles Calculation Study on the Interfacial Stability Between Zr and F Co-Doped Li6PS5Cl and Lithium Metal Anode" Batteries 11, no. 12: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120456

APA StyleZhang, J., Zhang, H., Chen, B., Ji, Y., Qian, C., Wang, J., Wang, Y., Bao, T., Chen, P., & Mei, J. (2025). First-Principles Calculation Study on the Interfacial Stability Between Zr and F Co-Doped Li6PS5Cl and Lithium Metal Anode. Batteries, 11(12), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120456