Evaluating Hybridization Potential Using Load Profile Metrics: A Rule-of-Thumb Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Hybrid Batteries

2.2. Use of Generative AI Tools

3. Cost-Optimal Sizing for Hybrid Batteries

- SoC Dynamics:

- Voltage Model:

- Current Model:

3.1. Example for a Single Load Profile

3.2. Web Application

4. Results

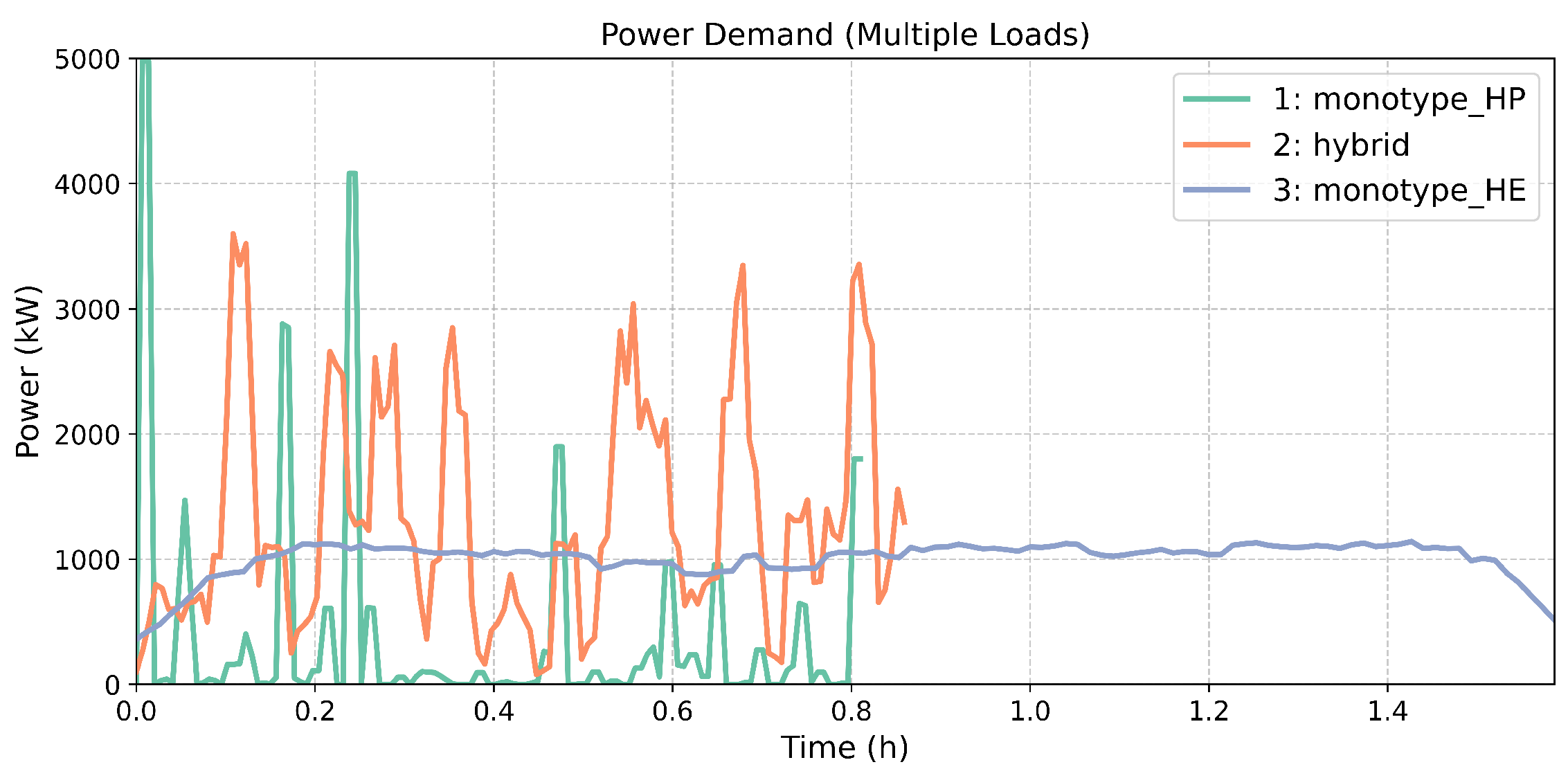

4.1. Load Profiles and Rules of Thumb

- Load profile C-rate < 1.5 C: The energy requirement is dominant, with relatively low power demands. In such cases, a single HE battery can also efficiently meet the peak power requirements without the need for a high-power supplement. Hybridization will introduce unnecessary complexity and cost. Since the SoC limits are defined between 10% and 90%, only 80% of the battery is effectively used, resulting in a value of 1.2/0.8, which equals 1.5. The generalized equation of the line that approximates the boundary between an optimal monotype HE solution and optimal HBESS solution therefore is:with the energy content of the load profile, the C-rate of the HE battery, and the useful range of the battery cells, in this work taken as equal to 80%.

- Load profile C-rate > 6.25 C: The load profile is highly power-intensive, often characterized by short-duration, high-current pulses. Here, an HP battery alone will suffice, as the energy demand is minimal and can just be provided by the HP battery. The generalized equation of the line that approximates the boundary between an optimal monotype HP solution and optimal HBESS solution therefore is:with , the energy content of the load profile, , the C-rate of the HP battery, and , the useful range of the battery cells, in this work taken as equal to 80%.

- Load profile C-rate between 1.5 and 6.25 C: This intermediate regime represents a balanced demand for both energy and power. Hybrid systems excel in this range by dynamically allocating power delivery: the LTO battery handles transient peaks, reducing stress and degradation on the NMC battery, which, in turn, manages the bulk energy supply. The cost reduction of a hybrid battery is at its maximum where the cost of a monotype HP and monotype HE battery would be approximately equal. This can be formulated as:with , the energy content of the load profile, , the cost of the HP battery per kWh, , the cost of the HE battery per kWp, and , the useful range of the battery cells, in this work taken as equal to 80%.

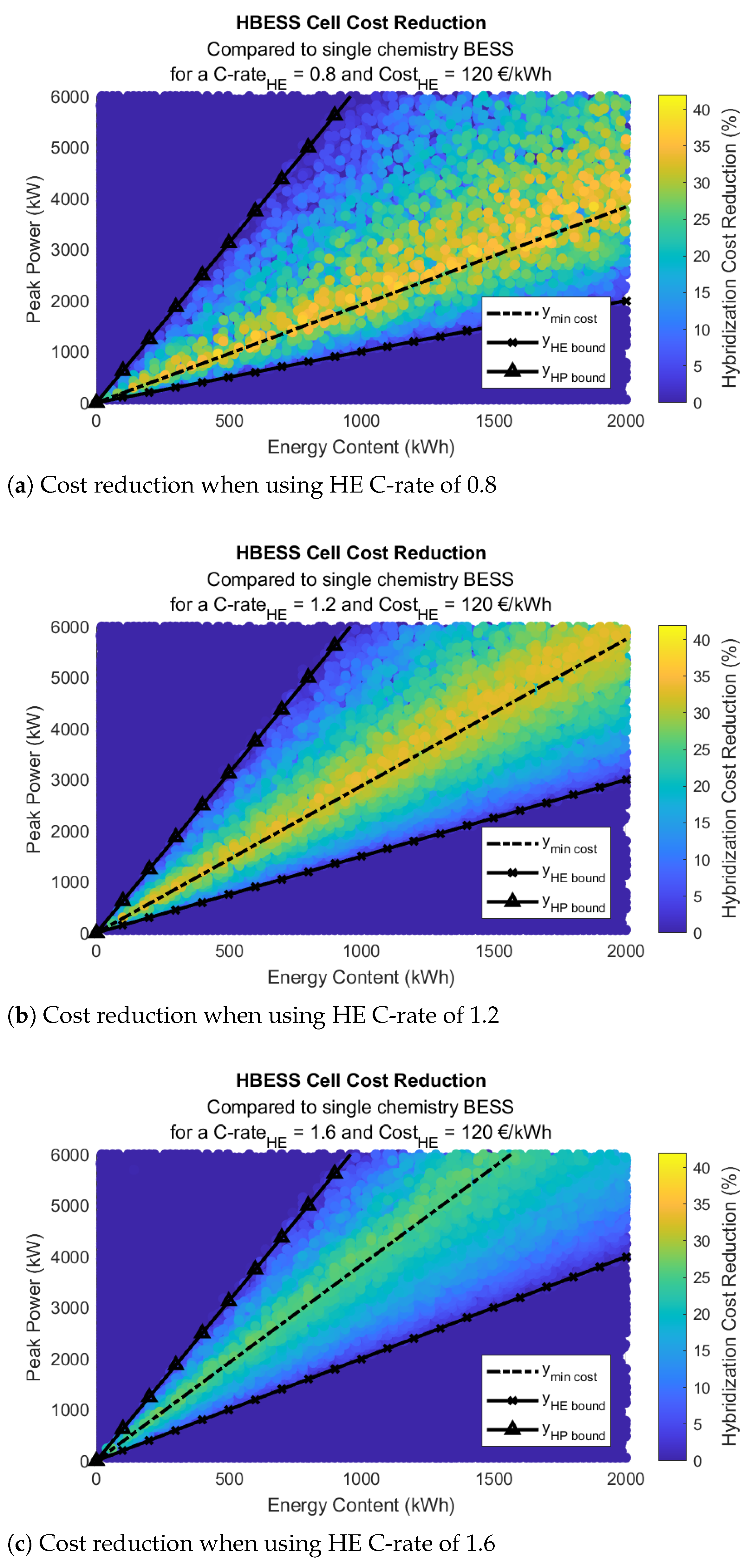

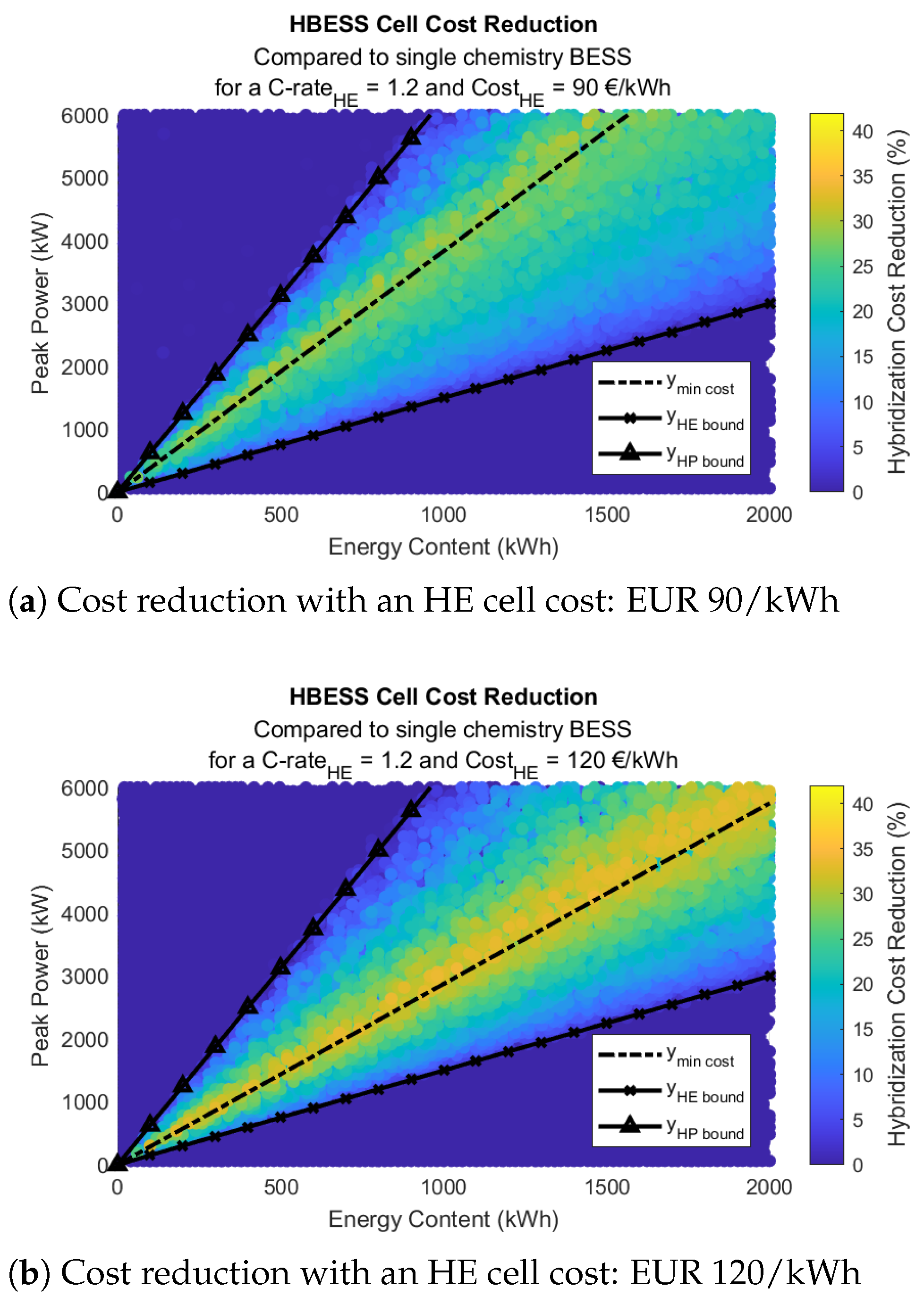

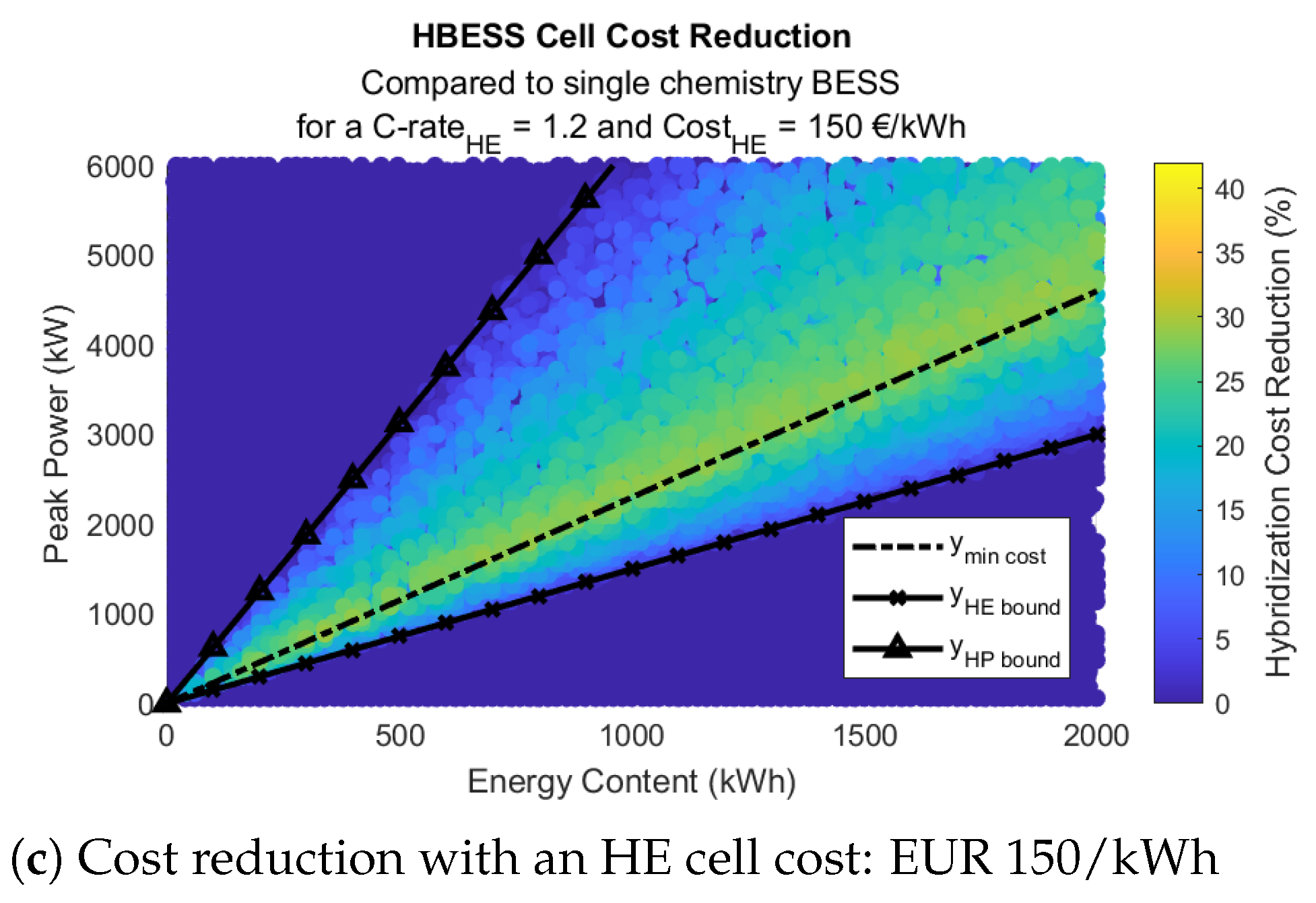

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis

4.2.1. Sensitivity to the C-Rate

4.2.2. Sensitivity to the Cell Cost

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HBESS | Hybrid Battery Energy Storage System |

| HE | High-Energy Battery |

| HP | High-Power Battery |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| MINLP | Mixed Integer Nonlinear Programming |

| NMC | Nickel Manganese Cobalt |

| LTO | Lithium Titanate Oxide |

References

- Nemeth, T.; Kollmeyer, P.J.; Emadi, A.; Sauer, D.U. Optimized operation of a hybrid energy storage system with lto batteries for high power electrified vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Detroit, MI, USA, 19–21 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, M. A Review on the Selected Applications of Battery-Supercapacitor Hybrid Energy Storage Systems for Microgrids. Energies 2019, 12, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, C.V.M.; Ramesh, R. Review of battery-supercapacitor hybrid energy storage systems for electric vehicles. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, M.; De Smet, J.; Stuyts, J. Battery Hybrid Energy Storage Systems for Full-Electric Marine Applications. Processes 2022, 10, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Barrera-Cardenas, R.; Akbarzadeh, M.; Mo, O.; De Smet, J.; Stuyts, J. Design and Evaluation Framework for Modular Hybrid Battery Energy Storage Systems in Full-Electric Marine Applications. Batteries 2023, 9, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, M. Hybrid lithium iron phosphate battery and lithium titanate battery systems for electric buses. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 67, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Chiu, C.Y.; Hung, Y.H.; Jen, K.K.; You, G.H.; Shih, P.L. An Optimal Sizing Design Approach of Hybrid Energy Sources for Various Electric Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, F.; Barbu, C.; Sarikurt, T. Optimal sizing of hybrid high-energy/high-power battery energy storage systems to improve battery cycle life and charging power in electric vehicle applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radrizzani, S.; Riva, G.; Panzani, G.; Corno, M.; Savaresi, S.M. Optimal sizing and analysis of hybrid battery packs for electric racing cars. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 5182–5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Arcanjo, A.; Vasconcelos, A.; Silva, W.; Azevedo, C.; Pereira, A.; Jatobá, E.; Filho, J.B.; Barreto, E.; Villalva, M.G.; et al. Development of a method for sizing a hybrid battery energy storage system for application in AC microgrid. Energies 2023, 16, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascalu, A.; Sharkh, S.; Cruden, A.; Stevenson, P. Performance of a hybrid battery energy storage system. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atawi, I.E.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Magableh, A.M.; Albalawi, O.H. Recent Advances in Hybrid Energy Storage System Integrated Renewable Power Generation: Configuration, Control, Applications, and Future Directions. Batteries 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Castelli-Dezza, F.; Cheli, F.; Tang, X.; Hu, X.; Lin, X. Dimensioning and power management of hybrid energy storage systems for electric vehicles with multiple optimization criteria. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 5545–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, T.; Schröer, P.; Kuipers, M.; Sauer, D.U. Lithium titanate oxide battery cells for high-power automotive applications–Electro-thermal properties, aging behavior and cost considerations. J. Energy Storage 2020, 31, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Deng, W. An adaptive energy management system for electric vehicles based on driving cycle identification and wavelet transform. Energies 2016, 9, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckx, S.; Monsieur, M.; Singh, T.; Surti, A. Output-Constrained Linear Decision Trees for Optimal Energy Management Approximation of Hybrid Batteries. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2025, 59, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | NMC | LTO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | Ah | 50 | 50 |

| Voltage | V | 3.65 | 2.3 |

| C-Rate | C | 1.2 | 5 |

| Resistance | 0.0006 | 0.0011 | |

| Cost per kWh | €/kWh | 120 | 230 |

| Cost per kW peak | €/kWp | 100 | 46 |

| Energy per kg | Wh/kg | 222 | 99 |

| C-Rate HE | C-Rate HP | Ratio Peak Power-to-Energy Content for HBESS Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 4.0 | 1.00–5.00 |

| 0.8 | 5.0 | 1.00–6.25 |

| 0.8 | 6.0 | 1.00–7.50 |

| 1.2 | 4.0 | 1.50–5.00 |

| 1.2 | 5.0 | 1.50–6.25 |

| 1.2 | 6.0 | 1.50–7.50 |

| 1.6 | 4.0 | 2.00–5.00 |

| 1.6 | 5.0 | 2.00–6.25 |

| 1.6 | 6.0 | 2.00–7.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weckx, S.; Surti, A.; Tao, Z. Evaluating Hybridization Potential Using Load Profile Metrics: A Rule-of-Thumb Approach. Batteries 2025, 11, 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11100381

Weckx S, Surti A, Tao Z. Evaluating Hybridization Potential Using Load Profile Metrics: A Rule-of-Thumb Approach. Batteries. 2025; 11(10):381. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11100381

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeckx, Sam, Ankit Surti, and Zhenmin Tao. 2025. "Evaluating Hybridization Potential Using Load Profile Metrics: A Rule-of-Thumb Approach" Batteries 11, no. 10: 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11100381

APA StyleWeckx, S., Surti, A., & Tao, Z. (2025). Evaluating Hybridization Potential Using Load Profile Metrics: A Rule-of-Thumb Approach. Batteries, 11(10), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11100381